Parade (ballet)

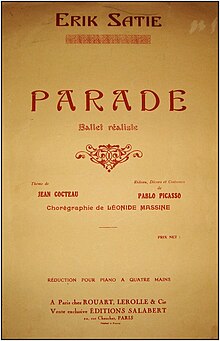

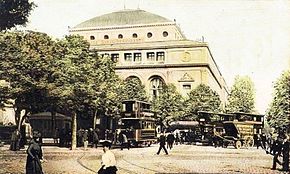

Parade - Ballet réaliste is the title of a ballet in one act based on a theme by Jean Cocteau and with music by Erik Satie , who composed it for Sergei Djagilev's Ballets Russes in 1916/1917 . Pablo Picasso designed the costumes, the curtain and the set . The ballet premiered on May 18, 1917 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris in the choreography of Léonide Massine , conducted by Ernest Ansermet , and caused a scandal. Parade is considered to be the key work and the starting point of an "advanced form of multimedia (dance) theater". In a previously unknown form of cooperation, outstanding personalities from the Parisian and international avant- gardes realized their individual inspirations and ideas in a collectively created stage spectacle in 1917.

action

Parade shows a group of showmen giving samples of their art on the street in front of the fairground in order to lure the audience into their show booth. A French and an American manager do the advertising. A Chinese magician and a pair of acrobats show their attractions: The Chinese magician juggles a chicken egg, the two acrobats show their skills on the high wire and on the trapeze . An American girl comes by and takes pictures. A horse, mimed by two actors, has to get to its feet and prance. However, the audience stays away.

Score and music

Erik Satie's score , which took the composer over a year with interruptions, has a playing time of around 15 minutes and consists of the seven composition numbers Choral , Prélude du Rideau Rouge , Prestidigitateur Chinois , Petite Fille Américaine , Acrobates , Final and Suite au Prélude du Rideau Rouge . In the course of the ballet, however, you can choose between three versions, which differ in details: the scenario by Jean Cocteau , the actual score and a piano reduction for four hands , which contains valuable information on the connection between the plot and the music. Satie's composition contains the molded part Ragtime Rag-time du Paquebot , behind which hides a quote from the Broadway song That Mysterious Rag by Irving Berlin and Ted Snyder from 1911, which was published in 1913 by the Moulin-Rouge -Revue Tais-toi, tu m'affolles had become known in Paris. The rest of the music consists almost entirely of a "static sound decor, which strings its homogeneous four-, eight- and twelve-bar groups according to a 'modular method'."

The “Scenario of Cocteau” contains the numbers Prestidigateur Chinois , Acrobates and Petite Fille Américaine , the arrangement of the four-hand piano reduction shows the arrangement Prelude du Rideau Rouge , Premier Manager , Prestidigateur Chinois , Petite Fille Américaine , Rag-time du paquebot , Acrobates , Supprème Effort et Chute des Managers and Suite au Prelude du Rideau Rouge . The vocal score and the score "agree in the bracketing of the ballet by the overture-like fugue" in the Prelude du Rideau Rouge and the only slightly changed repetition in the Suite au Prelude du Rideau Rouge .

The music, which is occasionally claimed to be “cubist”, is classified as neoclassical due to the ABA structure of its individual movements , especially since the “breaking up of contexts and their asymmetrical reassembly typical of cubist technology” is missing. The finale consists of the fast ragtime, the first ever composed in Europe, with which the showmen try unsuccessfully in their number sequence to attract visitors, and which Satie therefore wanted to have played sad in the end.

The score contained different types of noises, like noisy “instruments”, which gave the parade the avant-garde touch and moved the audience and press to fierce resistance, such as bottle games , “puddles of sound”, lottery wheel, typewriter, fog horn, electric bell, revolver shots and two sirens . For this reason , Parade is formally identified as "[...] as a dance suite with jazz and noise elements". Jean Cocteau added these so-called "trompes l'oreilles" (false ears) to the music with the consent of Satie; he considered them "indispensable for the specification of his figures". The use of everyday noises may have been a suggestion from Italy, where the ballet was planned. According to the manifesto “Musica futuristica” by Francesco Balilla Pratella from 1911, the Italian music futurists rejected the common musical instruments and instead composed their works from noises . They wanted “the great innermost motifs of tone poetry to be the realm of the machine and the victorious Add rule of electricity ”.

Emergence

Jean Cocteau had the first idea for a ballet in the spring of 1913 when he saw Le Sacre du printemps by Igor Stravinsky , conducted by Sergei Djagilew and choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky . His plan to develop a ballet based on the biblical David theme in a circus setting with Stravinsky failed. With the idea of a ballet parade that should show how circus performers try to get the attention of their audience for their performance, he met Dyagilev's interest. Circus, acrobat and showman atmosphere had been in vogue for nearly thirty years by this time. As a variant of the bohemian , it was an idealization and poetization of the gypsies and the traveling people since the 18th century. Even Edgar Degas drew 1874/75 dancers, and Paul Cézanne painted in 1881 Pierrot and Harlequin , followed by other Harlequins in the years 1888 to 1890. Georges Seurat painted his circus in 1891, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec created in 1899 with 39 leaves the title Au Cirque , inspired by his visits to the Nouveaux Cirque on rue Saint-Honoré in Paris, which has been the meeting place of the "monde élégant" since 1880. After Toulouse-Lautrec, Pablo Picasso created several motifs from the world of actors and artists, such as Les Saltimbanques, during his “ Pink Period ” in the winter of 1904/05 . The closest connection to Parade , however, is his cubist harlequin , made in 1915 , which Jean Cocteau saw in Picasso's studio in November of this year.

Jean Cocteau heard Erik Satie's Trois morceaux en forme de poire in a concert in 1915 and turned to the composer with his idea. Satie, who had never written a composition for a ballet, agreed. The production of the ballet Parade began during the First World War in 1916/1917. The choreography was done by Léonide Massine, master dancer of the Ballets Russes, lover of Dyagilev and replacement for Vaslav Nijinsky, who had left Paris shortly before the outbreak of the World War. Pablo Picasso, who had met Cocteau through Edgar Varèse in 1915 and was invited by Cocteau in May 1916 to create the design and decor for Parade , agreed to participate in August of the same year; he designed the set , the costumes and the stage curtain. In February 1917 Cocteau and Picasso joined the group of Ballets Russes around Dyagilev, Massine, Stravinsky and Léon Bakst in Rome to prepare the performance from February 19 to April 9. While working in Rome, Picasso fell in love with one of Djagilev's dancers, Olga Chochlowa , whom he married in Paris in 1918.

The independence of the participating artists became a problem. While Satie got on well with Picasso, he complained about Cocteau, who wanted to create the impression that Parade was his own, which put a lasting strain on the relationship between Satie and Cocteau. In financial terms, Satie, who was always in need of money, was preferred. The contract signed in January 1917 between the three artists stated that Cocteau would receive royalties of up to 3,000 francs for each performance and then cede them in full to Satie. Any additional amounts would be shared between the composer and the librettist. The set designer Picasso came away empty-handed.

Suzanne Valadon : Erik Satie , 1893

Valentin Alexandrowitsch Serow : Sergei Djagilew , 1909

Amedeo Modigliani : Pablo Picasso , 1915

First performance in 1917

Parade was the first collaboration between Satie, Cocteau and Picasso, their first engagement with a ballet, and their first joint production with Dyagilev and the Ballets Russes. The production marks the beginning of a new combination of the different arts in the classical modern of the 20th century.

Furnishing

| Stage curtain for the ballet "Parade" |

|---|

| Pablo Picasso , 1917 |

| 1060 × 1724 cm |

| Center Pompidou, Paris

Link to the picture |

When designing the stage and the costumes, Picasso followed Cocteau's basic idea of a collage of theater, circus, variety and city life. He designed the stage set as a prospectus of abstract high-rise buildings with a passage crowned by a lyre and provided with a white curtain that could be opened for the dancers' performances; in front of it, a suggested railing on both sides pointed to the entrance to a fairground on the proscenium .

Picasso used corrugated cardboard, cloth, metal and junk goods that he found in and near the Théâtre du Châtelet for the almost three-meter-high figures of the managers with whom Cubism came onto the stage in the production . The American manager consisted of elements such as a cowboy wardrobe, a lasso, a skyscraper with a smoking chimney, an oversized pistol holder vest, a billboard with the inscription PA / RA / DE and an oversized megaphone , and the French manager came in the form of the cosmopolitan dandy with attributes like a pipe , Tailcoat and mustache, flanked by the trees on the boulevards, hence.

Picasso's and Cocteau's ideas about the characters in ballet were inspired by current entertainment culture; For example, the magician was inspired by the cartoonist Chung Ling Soo, who travels through Europe, and the American girl Pearl White and Mary Pickford , well-known actresses in silent films , were the godfathers. For the Chinese magician, Picasso designed a brightly colored fantasy costume in yellow, red and black with snail appliqué that distributes the colors in free areas and lines. The American girl was tucked into her street clothes, a sailor's dress with socks, and was given an oversized bow on her head. The acrobats, on the other hand, wore their work clothes: blue and white, skin-tight jerseys.

While Picasso's stage design and the costumes of the two managers showed a cubist language of forms, he changed the stage curtain at the last moment, inspired by the Italian art of the 19th century. Picasso painted a group of showmen and comedians in a dreamy atmosphere, with a winged white horse in front of the romantic backdrop of a landscape with ruins; as soon as the curtain was opened, the cubist scenario of the city with the managers appeared. The curtain on which Satie's chorale sounded disappointed the intellectual audience. Léon Bakst criticized the curtain as not being avant-garde, but rather too "passéiste" (old-fashioned).

Staging

Immediately after Satie's completion of his score, rehearsals for the ballet began in Rome in early 1917, during which Picasso increasingly influenced the performances on the stage with his ideas. The production speculated on bringing the traveling people closer to an audience that was familiar with urban life on the boulevards . Satie had built everyday noises into the music, which Cocteau now wanted to add to his libretto with megaphones of gibberish - an idea that failed because of resistance, especially from the ballet troupe . The choreographer Massine, who was hardly familiar with the cultural western world, studied their gestures and translated them into danced characters. His choreography thus characterizes the characters on the street through elements of their everyday life, the cultural codes are demonstrated symbolically; the appearances follow a simple structure.

The first to appear are the managers, whom Massine lets stamp across the stage like living advertising signs. In the following three performances by the Chinese magician, the little American girl and the artist couple, they mark the transitions like guardians or number girls. Monstrously furnished in a cubist manner by Picasso, they appear as stereotypes of the world of business and money. The Chinese magician, who Leónide Massine danced himself, is a funny person who conjures up an invisible egg with nimble, puppet-like agility, eats it and then collects it on the tip of her shoe with the intention of making a longed-for audience curious about further magic tricks. The ensuing appearance by the American girl, danced by the ballerina Marie Chablenska in 1917, is choreographed as a quick sequence of movements based on trembling silent film images, in which the girl rides a bicycle like Charlie Chaplin runs, chases a crook, boxes and dances ragtime, sleeps, Shipwrecked and photographed. The artist couple shows their skills in tight-rope dancing and acrobatics on the trapeze in the traditional dance of the pas de deux .

| The horse in the ballet "Parade" |

|---|

| Pablo Picasso , 1917 |

| Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris

Link to the picture |

Originally a third manager figure was planned by Picasso and Cocteau, a "negro" in the form of a mannequin who was supposed to ride a horse given by two dancers. During one of the final rehearsals , however, the "negro doll" broke the horse construction in two, at the dress rehearsal it fell down to the general amusement and was now completely abandoned. The horse, devised by Picasso, remained in the performance, in a strictly symmetrical choreography without music, in which Massine performed a repeated sequence of prancing, looking around, climbing, wiggling backside, looking around, lying down, prancing, etc. This is followed by the finale, which unites all the characters on stage and expresses their individual reactions to the absence of the audience.

scandal

When Picasso's curtain fell at the end of the performance on May 18, 1917, a tumult broke out in the hall, in which the loud rejection of the performance drowned out the applause . Similar to Alfred Jarry's Ubu Roi twenty years earlier , the performance of Parade was followed by a scandal . A critic of La Grimace wrote that the "inharmonious clown Satie" composed his music from typewriters and rattles and that his accomplice, the "bungler Picasso", speculated on the "never-ending stupidity of people". And Guillaume Apollinaire , “the poet and naive visionary” succeeds in making “all the critics, all the regulars of the Paris premieres, all the rags from the butter and the drunkards from Montparnasse into witnesses to the most extravagant and senseless of all the fateful products of Cubism.” Soviet writer Ilja Ehrenburg , a friend of Picasso who lived in exile in Paris , described the spectacular premiere in May 1917 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris as follows: “The music was modern, the set was semi-cubist [...] The guests on the ground floor ran to the stage and shouted piercingly: 'Curtain!' [...] And when a horse with a cubist snout performed circus acts, they finally lost their patience: 'Death to the Russians! Picasso is a Boche ! The Russians are Boches! '”Picasso's friends, however, were delighted.

The irritation of the audience by the unusual artistic work of Cocteau, Satie, Picasso, Massine and the dancers of the Ballets Russe was less decisive for the boos than the political disputes that took place in the middle of the war with Germany, which was a “drum fire from the chauvinists “Generated. Everything that was not French and did not strengthen French war morale was attributed to the enemy, the Boches . The public saw enemies in the avant-garde artists of Montmartre and Montparnasse, like the entire generation of artists of those years who were called the École de Paris . Since the two Parisian galleries, which had specialized in Cubist works, were in German ownership, “Cubist” was equated with “German”. The Cubist parade was viewed as treason.

The premiere had legal consequences. According to Gabriel Fournier (1893–1963), who provided a detailed account of the trial, there was a heated argument between Cocteau, Satie and Jean Poueigh, music critic of the Carnet de la Semaine , who wrote a bad review for Parade . Satie had written him a postcard with the text: “Monsieur et cher ami - vous êtes un cul, un cul sans musique! Signé Erik Satie ”(“ Sir and dear friend - you are an ass, an ass with no music! Drawn Erik Satie ”) The critic sued Satie and the police arrested Satie during the trial when he repeated,“ Cul! “Yelled. The sentence was eight days in prison. Satie did not have to serve the sentence due to interventions by high-ranking figures, provided he did not do anything within the five-year period. He declined the advice of friends to write an apology letter to the critic. Instead, he wrote an “eulogy for the critics”, which he gave in April 1918 as the opening of a concert of the “Nouveaux Jeunes”. In A Poet's Life Path, Cocteau described the reason for the scandal, which lies in the fact that the "battle" for Parade coincided with the bloody battle for Verdun .

Subsequent performances

Towards the end of 1917 the ensemble performed with a parade in Barcelona . The premiere took place on November 10th in the Gran Teatre del Liceu , which also performed the ballet in modern times (2006). In London , the premiere of the Ballets Russes on November 14, 1919 at the Empire Theater turned into a major cultural event. In December 1920, Parade was shown again by the Ballets Russes at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris. In May 1921 a resumption at the Parisian Théâtre de la Gaité Lyrique followed .

Seven years after the world premiere of Parade , Satie collaborated again with Cocteau, Picasso and Massine in 1924. The 15-minute ballet Les Aventures de Mercure was produced by Massine and Count Etienne de Beaumont and premiered on June 18 at the Théâtre de la Cigale in Paris as part of a series of avant-garde productions entitled “Les Soirées de Paris” , however, did not reach the attention of its predecessor.

reception

Guillaume Apollinaire described Parade – Ballet réaliste in the program booklet of 1917 under the title “Parade et l'Esprit Nouveau” as “a kind of super-realism (sur-réalisme)”, a word created by André Breton in “Homage to Guillaume Apollinaire “In 1924 he took over for his first surrealist manifesto, thus creating the term surrealism . In the program booklet, at the beginning of his text, Apollinaire noted a “new connection” between painting and dance, between sculpture and gesture - realized on stage by the painter Picasso and the “most daring of the choreographers, Léonide Massine”. He explicitly distinguishes therefore the cooperation of independent artists for the creation of an independent, "non-mimetic art" from the rejected by him form of Gesamtkunstwerk Wagnerian coinage from the 19th century.

Immediate effects

The scandal, which was also caused by the noises in the parade , was noticed in Zurich, whereupon Erik Satie was accepted into the Dada movement. Marcel Janco commented that "numerous writers, pamphleteers, scatologists, painters, musicians, inverted, [...] a large number of German writers, even diplomats [...]" claimed the Dada title for themselves, but without justification. On the other hand, he “would propose that certain great men be given this title ex officio”, such as Charlie Chaplin , Voltaire , Erik Satie, Niccolò Machiavelli , Napoleon Bonaparte , Pablo Picasso, Molière , Max Jacob or Socrates . The section “Rag-time du paquebot” was part of the program of Theo van Doesburg and Kurt Schwitters ' Dada tour as “Rag-time Dada” in a piano version that Stephane Chapelier (under the pseudonym “Hans Ourdine”) had created in 1923.

The music of the ballet inspired several young musicians to a new French art, they went to Satie and were considered his students. Among them were, for example, Francis Poulenc , who had a penchant for circus and fairgrounds, and Darius Milhaud , who had the closest relationship with the composer due to the mutual enjoyment of curiosities with Satie. They formed the Groupe des Six , founded in 1918. The critic and composer Henri Collet invented the name when he wrote a feature section about them in the magazine “Comoedia” with the headline “Les cinq Russes et les six Français”. It was a nod to the Russian group of five . Satie was their patron saint, Cocteau took over the sponsorship and paved their way into the concert halls. Henri Sauguet , who was close to the Groupe de Six, founded the Groupe des Trois in Bordeaux together with Louis Emié and Jean-Marcel Lizotte, whose first concert took place there on December 12, 1920 in the Salle del Mouly. The concert consisted of works by both groups as well as Erik Satie's parade .

Exhibitions and revivals

From the end of 2006 to the beginning of 2007, the Frankfurt Schirn presented more than 140 works by Picasso under the title Picasso and the Theater : designs for stage sets, photographs, costumes, stage curtains, drawings and paintings, including designs for parade . However, many of Picasso's original stage sets and costumes have been destroyed or lost. There are often only a few black and white photographs left of the original choreographies. In 2009/2010 at the Palais Garnier Bibliothèque-musée , Paris, in an exhibition of the Opéra national de Paris on the Ballets Russes, museum exhibits from the parade production of 1917 were represented.

In 2007 the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma put on the stage a reconstruction of Parade entitled “Serata Picasso Massine”. In 2009, the 35th Hamburg Ballet Days Parade , led by John Neumeier , was part of the performances on the occasion of the 100th birthday of the Ballets Russes, performed by the Donlon Dance Company from Saarbrücken. In 2010, Parade was performed as part of a homage to the Ballets Russes by the Ballet de Teatres in Madrid , re-choreographed by Ángel Rodriguez. On the tenth anniversary of the opening of the Pablo Picasso Graphics Museum in Münster, a new staging of the ballet took place in June and July 2010. The choreographer Claudine Merkel has redesigned the piece. The music for the new parade was written by the Münster composer Burkhard Fincke, the costumes by the designer Jean Malo. The oboist Stefanie Bloch from Münster accompanied the dancers.

In 2012, the Center Pompidou-Metz showed Picasso's stage curtain in its 1917 exhibition as an outstanding exhibit and emphasized that it was one of the most monumental works the artist had created.

literature

- Olivier Berggruen , Max Hollein (ed.): Picasso and the theater . With a foreword by Max Hollein and texts by Olivier Berggruen, Asya Chorley, Douglas Cooper , Marilyn McCully, Esther Schlicht, Alexander Schouvaloff, Ornella Volta, Diana Widmaier Picasso . German-English edition, Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern 2006, ISBN 978-3-7757-1872-1

- Heinrich Lindlar (Ed.): Rororo music manual . 2 volumes. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag GmbH, Reinbek near Hamburg 1973; Volume 2, p. 594

- Deborah Menaker Rothschild: Picasso's Parade . Philip Wilson Publishers 2003, ISBN 978-0-85667-392-4

- Andreas Münzmay: "That Mysterious Rag". How Erik Satie composes the strange relationship between theater and reality in “Parade”. In: Sidonie Kellerer, Astrid Nierhoff-Fassbender and Fabien Theofilakis (eds.): Misunderstanding / Malentendu: Culture between communication and disruption , studies on modern research . Vol. 4, Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 2008, pp. 225–241 ( limited preview in the Google book search)

- Robert Orledge: Satie the Composer . Cambridge University Press 1990; Pp. 222-245; P. 312 ( limited preview in Google Book search)

- Ricarda Wackers: Dialogue of the Arts. The collaboration between Kurt Weill & Yvan Goll . Publications of the Kurt-Weill-Gesellschaft Dessau, Volume 5. Waxmann, Münster 2004. P. 76–83 ( limited preview in the Google book search)

- Grete Wehmeyer : Erik Satie . Gustav Bosse Verlag, Regensburg 1974, ISBN 3-7649-2077-7 ; Gustav Bosse Verlag, Kassel 1997, ISBN 3-7649-2079-3 (revised new edition)

- Grete Wehmeyer: Erik Satie . Rowohlt's monographs. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-499-50571-1

Web links

- Parade. Ballet . Handwritten music notation by Erik Satie, 1917; with annotations by Léonide Massine and Jean Cocteau. (Digitized from the Beincke Rare Book & Manuscript Library , Yale University )

- Complete music notation from Erik Satie's Parade ; (audio)

- Modern Times - Satie, Picasso and Cocteau's Crazy Parade (English, with audio sample of the finale)

- Erik Satie (1866-1925). parade

- Picasso's Parade Ballet Costumes (English)

Videos :

- Ballet Parade (film)

- Teatro dell'Opera di Roma: Gli acrobati

- Teatro dell'Opera di Roma: Il manager a cavallo

- Ángel Rodriguez (Choreography): Hommage à Parade (2010)

- Jean Cocteau raconte la création de Parade avec Erik Satie et Picasso (French with English subtitles)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Ricarda Wackers: Dialogue of the Arts. The collaboration between Kurt Weill & Yvan Goll . Publications of the Kurt-Weill-Gesellschaft Dessau, Volume 5. Waxmann, Münster 2004. P. 78 ( limited preview in the Google book search)

- ↑ Erik Satie: Parade , dlib.indiana.edu, accessed July 9, 2018

- ↑ a b Grete Wehmeyer: Erik Satie . Regensburg 1974, p. 182.

- ↑ Andreas Münzmay: That Mysterious Rag. How Erik Satie composes the strange relationship between theater and reality in “Parade”. In: Sidonie Kellerer u. a. (Ed.): Misunderstanding / Malentendu . Würzburg 2008, pp. 225–241 ( limited preview in Google book search)

- ↑ Hans Emos: Montage-Collage-Musik (2009) p. 99 ( limited preview in the Google book search)

- ↑ a b c Grete Wehmeyer: Erik Satie . Gustav Bosse Verlag, Regensburg 1974, p. 202.

- ↑ Grete Wehmeyer: Erik Satie . Gustav Bosse Verlag, Regensburg 1974, p. 208.

- ↑ Ornella Volta: Satierik. Erik Satie . Rogener & Bernhard bei two thousand and one, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-8077-0201-6 , p. 52.

- ↑ Nancy Hargrove: The great Parade: Cocteau, Picasso, Satie, Massine, Diaghilev - and TS Eliot In: questia.com of March 1, 1998, accessed January 6, 2019.

- ↑ Grete Wehmeyer: Erik Satie . Regensburg 1974, p. 187.

- ↑ Score, Paris: Rouart, Lerolle et Cie., 1917

- ↑ Karin von Maur (ed.): From the sound of images. Music in 20th Century Art , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1985, p. 386.

- ↑ Ornella Volta: Satierik. Erik Satie , Munich 1984, p. 55.

- ↑ Grete Wehmeyer: Erik Satie . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1998, p. 93.

- ↑ Grete Wehmeyer: Erik Satie . Gustav Bosse Verlag, Regensburg 1974, p. 178 f.

- ↑ Erik Satie (1866-1925) , musicacademyonline.com, accessed November 26, 2010.

- ↑ a b Grete Wehmeyer: Erik Satie . Gustav Bosse Verlag, Regensburg 1974, p. 201.

- ^ William Rubin: Pablo Picasso. A Retrospective, with 758 plates, 208 in color, and 181 reference illustrations . The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Thames and Hudson, London 1980, p. 196.

- ↑ Jean Cocteau , jeancocteau.net, accessed November 26, 2010.

- ^ Siegfried Gohr : Pablo Picasso. Life and work. I do not search, I find . DuMont Literature and Art Verlag, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-8321-7743-4 . P. 24 f

- ↑ Grete Wehmeyer: Erik Satie . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1998, p. 95 ff

- ^ Carsten-Peter Warncke: Pablo Picasso. 1881-1973 . Volume I: Works 1890–1936 . Cologne 1991; P. 252.

- ↑ a b Karin von Maur (ed.): From the sound of images. Music in 20th Century Art , Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1985, p. 385.

- ^ A b c Nicole Haitzinger: EX Ante: "Parade" under frictions. Choreographic concepts in collaboration with Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso and Léonide Massine In: corpusweb.net , accessed on December 20, 2010.

- ↑ The Metropolian Opera : Background History on “Parade” ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , archive.operainfo.org, accessed December 23, 2010.

- ^ Cocteau, Picasso, Satie: Libretto von Parade , 1916, accessed December 20, 2010.

- ↑ a b Picasso: Parade. Histoire de Parade (French) , faisceau.com, accessed December 18, 2010.

- ↑ Video: Teatro dell'Opera di Roma, 2007 accessed on YouTube on December 20, 2010

- ↑ a b Grete Wehmeyer: Erik Satie . Gustav Bosse Verlag, Regensburg 1974, p. 209.

- ^ Wilfried Wiegand: Picasso . Rowohlt, Reinbek, 19th edition 2002, ISBN 978-3-499-50205-7 , p. 93 f

- ↑ Grete Wehmeyer: Erik Satie . Gustav Bosse Verlag, Regensburg 1974, pp. 209, 211.

- ↑ Grete Wehmeyer: Erik Satie . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1998, p. 98 f

- ↑ Parade , bcn.es, accessed on 20 December of 2010.

- Jump up ↑ The great Parade: Cocteau, Picasso, Satie, Massine, Diaghilev - and TS Eliot. (analysis of the first Modernist ballet 'Parade') In: Mosaic (Winnipeg). Volume: 31. Issue: 1, pp. 83ff., March 1998. University of Manitoba. Via questia.com , accessed January 6, 2016.

- ^ William Rubin: Pablo Picasso. A Retrospective, with 758 plates, 208 in color, and 181 reference illustrations , p. 225.

- ↑ Ruby Cohn: Surrealism And Today's french Theater , jstor.org, accessed December 17, 2010.

- ↑ a b c Ornella Volta: Satierik. Erik Satie , Munich 1984, p. 56.

- ↑ Ornella Volta: Satie et la danse . Plume, Paris 1992, pp. 14 and 34.

- ↑ Grete Wehmeyer: Erik Satie . Regensburg 1974, p. 223.

- ↑ Grete Wehmeyer: Erik Satie . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1998, p. 100.

- ^ Marc Wood: Henri Sauguet. Springing Surprises , jstor.org, accessed December 25, 2010.

- ↑ Picasso and the Theater , kunstaspekte.de, accessed on November 25, 2010.

- ^ Opéra national de Paris: Exposition Ballets Russes ; Photo gallery on Flickr (accessed December 29, 2010)

- ^ Teatro dell'Opera di Roma: Serata icasso Massine , 2009 ( Memento of September 18, 2011 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on October 2, 2012

- ↑ Hamburg Ballet Days end with Star Parade , focus online / dpa , July 13, 2009, accessed on July 6, 2018.

- ↑ Ángel Rodriguez: PARADE en Madrid en Danza 2010 , accessed on December 22, 2010.

- ^ Sabine Müller: With Picasso in the ballet . In: ruhrnachrichten.de June 9, 2010 (no longer available online)

- ↑ 1917 , centrepompidou-metz.com, accessed on July 24, 2012.

Illustrations

- ↑ Pablo Picasso: Stage design for a parade , 1917 (model)

- ↑ Photo: Marie Chabelska as a little American girl , 1917 (Photo: Lachmann), V&A Theater & Performance Collections

- ↑ Pablo Picasso: Photo: Artist's Trikot ( Memento from December 25, 2010 in the Internet Archive ), drawing 1917.

- ↑ Nicholas Zverev as acrobat , 1917 (Photo: Lachmann) V&A Theater & Performance Collections

- ↑ Pablo Picasso: Photo: Study for the Horse (with two actors and the hint of the doll) , 1916/17; Picasso Museum , Paris

- ^ Pablo Picasso: Photo: Study for Managers on Horseback , Studies for Parade , 1916/17; Picasso Museum, Paris