Persian literature

The history of Persian literature can be traced back to ancient times. The first examples of Iranian poetry, which already show the scheme of a rhetoric that has become a tradition , can be found in the gathas (chants) , the oldest parts of the Avesta , the script of the Zoroastrian religion (see also Zarathustra ). When Persian poetry , however, all of the classic is poetry culture in the Iranian Plateau referred to in the Persian literary language was made. It originated mainly in the area of today's Iran , Afghanistan , Tajikistan and Uzbekistan . In addition, the Persian language was the cultural and official language in Iraq , Pakistan and northern India for a very long time . Some of the most famous poets of the Persian language lived here too.

In the Persian culture and language area, poetry is highly valued, so that the Persian culture has produced a number of famous and successful poets. Persian poets have influenced other cultures and languages over the centuries, including the German poet Goethe , whose west-eastern divan is based on classical Persian poetry.

poet

Famous poets of the Persian style - Classical period

- Abu Abdullāh Dscha'far-e Rudaki (858–941), the first poet and father of the New Persian language . Born in a mountain village east of Samarqand , in today's Tajikistan, Rudaki was the official poet of the Samanid emir Nasr II (914-943), who, it is said, showered him with honors. He versified a famous collection of fables of Indian origin under the name of Kalila and Dimna , which in the Orient immense popularity enjoyed and later La Fontaine served as the main source of his fables. Only part of the extensive work that was awarded to him has survived. He left behind panegyric , funeral elegies , lovepoetry, Bacchian poetry, as well as narrative and moral poetry. Towards the end of his life, he was probably blinded because of his religious beliefs.

- Bu Shakor Balchi , author of the ( Persian آفرين نامه) Āfarīn-Nāme (letter of praise), written between 954 and 958 AD.

- Rābia-e Balchi or Zain al-'Arab , the first woman in Persian poetry.

- Abu Mansur Daqiqi -e Balchi (930/40 - before 980), was one of the most gifted poets of the 10th century . He worked as Paneyriker the local prince Tschaghaniens ( Transoxiana ), southeast of Samarkand , also in the Samanid Emir Mansur I. (961-976) and his son Nuh II (976-997) -. And can be a master of this genre are considered. However, he achieved fame as Ferdousi's predecessor. Before his untimely death - he was murdered by one of his slaves according to Ferdousi - he had already putinto versethe extensive prose material of the traditional national epic, which had previously beencompiledby four scholars from Tūs ( Chorāsān ) (near present-day Mashhad ) ( 961). Several thousand of these distiches were mentioned by Ferdousi in his Shāhnāme ( Persian شاهنامه) accepted. Although it has often been assumed that Daqiqi was of the Zoroastrian faith, passages from this (see Safā, 1964) rather suggest that this was a demonstration of sympathy by a great literature lover of very moderate Islamic faith.

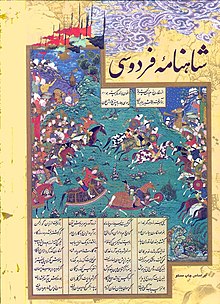

- Abu l-Qāsem-e Mansur ebn Hasan-e Ferdousi (* around 940-1020), born in the village of Bāž (Tabaran, the area of Tūs as the son of a landed noble family ( Dehqan ) ), is the author of the Persian national epic , the ( Persian شاهنامه) Shāhnāme (The Persian Book of Kings) . In more than 50,000 distiches he reports on the splendor of the Persian Empire before the invasion of the Arabs in the 7th century.This epic, which is one of the best of its kind, served as a template for further epics in the Persian language and was first translated into Arabic and Turkish , later into many other languages (mostly in excerpts). From the very beginning of his youth, Ferdousi versed some prominent episodes of Persian history , but only around 980, when he learned of the murder of Daqiqi, did he take up the project he had started. Around 994 he had already versed the version drawn up by Abu Mansur in 957, which served as the source of al-Bondari's Arabic prose translation (13th century). Then he used other sources to complete his work: u. a. the memoirs of Tsarir, the exploits of Rostam and Alexander the great . Around 1010 he had finished his work, which he then dedicated to Mahmud of Ghazni . After he had fallen out with this, however, Ferdousi left Ghazni and settled in various places, including a. Herāt , Tus, Tabaristan and Chorāsān. The greatness of Ferdousi lies in the conscientiousness in the use of his sources, his skill in the representation of nature, as well as the representation of the warlike and heroic episodes, as well as the interweaving of moral admonitions in these descriptions. His clarity and simplicity of style and vocabulary made him a role model for other poets. There are two important introductions to the Shahname: one by the Timurid prince Bai Songhor (15th century), as well as another, older one, which partly reproduces that Abu Mansur al-Mommari, which he gave in 957 at the request of Abu Mansur Mohammad ebn Abd or-Razzaq had prepared a prose version.

- Bābā Tāher (approx. 944-1019), one of the first important poets ofSufism, whose poems, accompanied by instruments, often serve as the basis ofclassical Persian music.

- Farrochi († 1037), generally highly esteemed author ofghazalsand panegyrics (eulogies), court poet of theGhaznavids.

- Abu Qasem Hasan Onsuri Balchi (988? -1040), author of Ghaznavids . He wrote delicate, demanding Ghazals and Qassids (Qasidas) ( odes and panegyric),original in their choice of themes, which served as models for many of his successors. He also versed some old legends such as B. Wameq and Asra and Rostam and Sohrāb (see also Ferdousi (The Death of Sohrāb) ).

- Manutschihri († 1040) poet at the court of theZiyaridsandGhaznavidswith a strong influence ofArabic literature, which he skillfully brought in when writing his poems. He expanded the facets of theBacchianpoems.

- Gorgāni († 1054), poet at the court of theSeljuks, he was the author of one of the best epics in the Persian language,Wis and Rāmin, which served as a model for other epics, such as Chosrau and Shirin ofNezāmi, and a connection between thepre-Islamicand Islamic Iran established.

- Asadi (Abu Nasr Ali ibn Ahmad Tusi ) († 1072), b. in Tus (nearMashhad), incorrectly referred to as MasterFerdousis, author ofdebates(Monāzer), thebook Garschāsp (Garschāspnāme), the best epic after theShāhnāmeFerdousis - also author of panegyric (eulogies) and author of one of the oldestdictionariesin Persian Language in which he collected rare words and words from Persian poetry(Loghat-e Fārs). First he lived in Chorāsān (at the court of the Ghaznavids), later inAzerbaijanwith the princes of the region there. In his main work,Garchaspnāme, he tells of the fabulous achievements ofGarchasp,Rostam'sancestor. After listing the line of ancestors, he reports in detail about his travels and stays in different countries, his struggles there, his conversation withBrahmanand with other sages - as well as the manners and customs of the foreign peoples he visited in connection with admonitions and advice to the reader. His strength lies above all in the descriptions, the word combinations, his sentence structure and the choice of expressive and subtle images. Some orientalists wrongly distinguished between a so-called son and father for a long time, butthis was refutedby Safā in hisHistory of Literature in Iran, II, p. 404ff. (Edition Garchaspnameh: Yaghmai(Teheran 1918), translation and edition of the first third: Clément Huart (1926), the other two thirds by Henry Massé (1950))

- Amir Nāser Chosrou -e Balchi (1003-1075), born in Gobadian (in the Balch region). After he was well educated, in 1045 he went on a pilgrimage to the holy cities of Islam. He then stayed for some time in Egypt , where he followedthe Ismailite doctrine , and was thendelegated to Khorasanby the Fatimid caliph . Troubled by the Orthodox in the region, he withdrew to the canton of Badakhshan, where he retired in Yomgan and took over the spiritual leadership of the Ismailis. At the same time he wrote his theological and philosophical treatises and also created an extensive collection of poems, which made him one of the most powerful thinkers in Iran. His poems, shaped by the influence of his theological education, are full of sentences and exhortations that he applies logically, shaped by his scientific thinking. At the same time, his poetry is full of ornate and subtle inventions, and his poetic language is reminiscent of that of the last poets from the Samanid period . In prose, he was one of the first to write philosophical or scientific questions in a language that was clear in style and firm in tone. His travelogue Safarnāme , which he also wrote in prose, is also a model of the simple and precise style as well as ( Persian روشنايى نامه) Roschnainame .

- Chwadscha Abdollāh Ansāri (1006-1089), "Pir of Herāt" (the sage (old man) of Herāt) , important Sufi poet and author of the Monādschātnāme ( Persian مناجات نامه), the Book of Psalms .

- Irān Shāh (approx. † 1117), contemporary of the Seljuk Sultan Malek Shāh II , wrote an epic around 1106 in which he reports on the “high deeds” of the hero Bahman, the son of Esfandiārs - one of the main elements of the national epic in Iran. (including Barzin and the dragon , the fight between Barzin and Bahman , self-knowledge ) (see also: Safā, Hamāse Sarā'i dar Irān (story of the heroic epic in Iran) , 1945)

- Omar Chayyām (1048–1131 or 1132), (poet, philosopher, mathematician and astronomer), student of the doctor, scientist and poet Avicennas , worked at the court of the Seljuk ruler Malek Schāh I (1072-1092). During his lifetime he distinguished himself primarily as a mathematician, philosopher and astronomer and participated in the reform of the Iranian calendar . In this context he also wrote the Nouruzn āme ( Persian نوروز نامه), (New Year's Book), a treatise on New Year's customs in ancient Iran. After his death, Chayyām was best known for his Rubā'yyāt , the quatrains , which were kept relatively critical. Example of a quatrain in the translation by Max Barth : Say who is sinless here on earth? / Who could live without ever being absent? / If you do wrong to me for wrongdoing, what is the difference between me and you?

- Moezzi (1124-1127) was a laureate poet of the Seljuq ruler Malek Schāh I (1072-1092). He spent his youth in Herat and Esfahan . He wrote excellent Ghazals and contributed to the renewal of the Qasids, which until then had been strongly influenced by their Arabic origins.

- Sanā'i (approx. 1080–1157), born in Ghazni in the middle of the 11th century, began his career as a poet at the court of the Ghaznavids Ebrahim (1098–1114) and Bahmanschāh (1117–1157). After he finally settled in Chorāsān, he was instructed by several poets in the mystical poetry, in which he developed his own style, which made him one of the first great masters of this genre . His work thus forms a milestone in Persian literature. In addition to his lyrical works , he left behind some Masnawis of high spirituality.

- Raschid ad-Din Vatvat (approx. 1088 / 89–1182 / 83), the court poet and "State Chancellor" of the Khorezm Shahs from the Anushteginid dynasty (especially of the Ala ad-Din Atsiz '), wrote primarily artistic panegyries Poems of praise, but also left behind a multitude of impressive letters and an important handbook of rhetorical figures called "The gardens of magic in the subtleties of poetry" . The committed private scholar spent most of his long life in the Khorezmian capital of Gurganj .

- Anwari - also Anvari and Enweri - († 1187), one of the most esteemed authors of panegyric (eulogies) of the Persian language. First he studied the "classical disciplines" (literature, philosophy, mathematics and astrology), then he hired himself out at the court of the Seljuq Prince Sandschar . Model for authors of quasids. Wrote the best Ghazelas until Sa'di's appearance .

- Modschir († 1197) from Beilaqan, a city in Azerbaijan now in ruins . He is considered one of the best panegyric writers of his time. Disciple of Chaqani (albeit with a clearer style), against whom he later wrote satirical verses . Lived first at the court of the Atabegs of Azerbaijan , later at the court of the Seljuk Arslan ibn Toghril. He died in Esfahān , where he was murdered.

- Elyas ebn-e Yusof Nezāmi -e Ganjawi (1141–1209), born in the city of Ganja , today's Gəncə in the Caucasus (Azerbaijan), Nezāmi lived far away from the courts of the rulers, but he dedicated his works, according to the custom of Time, the princes of Azerbaijan. He is one of the masters of Persian literature. Nezāmi wrote a Dīwān with important mystical lyric poems, five Masnawis, the Chamse (literally: collection of five ) or Pandsch Ganj (Five Treasures) with didactic and moral poems, as well as some novels (in verse) that refer to old Sassanid or Arabic Legends related. In unexpected combinations of words , Nezāmi expresses subtle thoughts, combining the entire Persian cultural heritage (literature, science, philosophy) with an unsurpassed skill of his own. The words and metaphors chosen by himare always necessary to maintain the overall harmony of his works and the like. a. Sharaf name ( Persian شرفنامه) chosen.

- Farid od-Din Attār (1136–1220) is one of the most important representatives of Sufi poetry in Iran. At first he worked as a druggist (pharmacist) in his hometown of Nischapur (from which his name Attār = druggist is derived). As a poet he left an extensive body of work. In addition to a prose collection of biographies of the Sheikh Sufis , the “Memorial Book of the Saints” and a lyrical divan, he also left various Masnawis, including “ The Birds Conversations ” and “The Seven Cities of Love”. Masnawis are in a simple style, instructive, deeply felt and moving sentences , embellished with a series of anecdotes and parables . He died probably in 1220 at the time of the capture of Nishapur by the Mongols .

- 'Erāqī from Hamadān (1213–1289), one of the famous mystical poets of the 13th century. At the age of 18, after completing a literary and scientific education, he moved to India (Hindūstān), where he settled in Multan under the Sheikh Bahā od-Din Zakariya . He later traveled to Arabia and Asia Minor , where he studied under Sheikh Sadr od-Din of Konya , a student of the famous Arab mystic Muhyī ad-Dīn ibn al-'Arabī . Then he traveled again to Egypt and Syria, where he also died. He was buried near the tomb of Muhyī ad-Dīn s. He left behind a sofa with different poems, a Masnawidichtung , 'Oššāqnāme (Book of lovers) , in which he describes the gradations of mystical love and one in prose written treatise , which later by Jami was commented. He can be described as a perfect mystic who expresses himself in a clear and definite, but at the same time passionate form, whereby he also thinks about the teaching (mediation) of mysticism.

- Moṣleḥ ad-Din Sa'di Schirāzi (* beginning of the 13th century - 1291 or 1294) is one of the most famous poets of Persia. Sa'di spent his youth in Baghdad , where he firststudied literature and religious studies. He then traveled to Iraq , Syria and Hijaz . In the middle of the century he returned to Schirāz , his birthplace, where he completed his two famous collections of moral anecdotes, the Bustān written in verse(1257) and the versed prose work Golestān (Rose Garden) (1258). After that he ledthe life of a hermitoutside of Shiraz . Along with Ferdousi , Hāfez and Nezāmi, he is one of the greatest poets in Iran. He masters the Persian language like hardly anyone else, which is evident in his sentences and proverbs . His works are eloquent, fluid and captivating at the same time. His ghazals are also extremely graceful. In addition to the works already mentioned, he wrote some less extensive prose writings, including some essays and the advice for the rulers . Here is one of his poems in the translation by Friedrich Rückert : O you born of a woman / Are you not members of one body? / Can a member also fall into pain / That it is not felt by everyone? / You who are not touched by human suffering, / You can't even use the name human. (Trivia:This poem Sa'dis can be foundabove the entrance to the UN .)

- Jalāl od-Din Rumi (1207–1273, called Moulawi, Mevlana or Moulanā ) was the best-known and perhaps most popular representative of Sufi poetry . Born in Balch , he accompanied his father as a child due to the Mongol invasion to Asia Minor, where the family settled in Konya . Taught by his father Bahā od-Din Mohammad and his student Borhān od-Din Mohaqqh from Termez , he completed his studies in Syria. Back in Konya, he taught theology. On this occasion he made the acquaintance of the mystic Chams od-Din Mohalal ebn Ali Tabrizi , under whose influence he developed great enthusiasm for mysticism , which shaped him in the last thirty years of his life. During this time he also wrote his great works. His Masnawi is one of the masterpieces of mystical literature . Here he deals with the most important religious and moral questions, which he alsoillustrateswith anecdotes and traditional proverbs . His Ghazale, which hededicatedto his teacher Chams od-Din Tabrizi , are also extremely sublime and testify to great lyrical beauty. He also wrote a collection of quatrains ( Rubāʿī ), a mystical treatise and prose pistles . His style, which reflects the tradition of the poets Khorasan, is simple and remarkably straightforward.

- Schams od-Din Mohammad Hāfez or Hāfez-e Schirāzi (* beginning of the 14th century - 1389) is one of the greatest in Persian literature and is also the best-known Persian poet abroad (he was alsohighly valuedby Goethe ). With the exception of short trips to Yazd and Esfahān , he spent most of his life in his native town of Shiraz , where helived very modestlyas a scholar and despite the respect heenjoyedat the court of the Mozaffarid princes in his native town. Nevertheless, there were phases of disfavor at court, which was painfully reflected in his works - and so he approached Shāh Choda (1357–1383). Be aware of his genius, he allowed himself to hold back when writing panegyrics (eulogies) and his protégé also be mentioned only in hints in his Ghazalen. Even if Hāfez 'work is less extensive than that of other Persian poets, it shows a tremendous wealth of facets, nuances and quick-wittedness, although it has remained accessible to a large audience over the centuries. Hāfez is one of the most popular poets in Iran and his divan is generally used as a means of prophecy. His poetry, both mystical and cosmopolitan, testifies to an uncommon verbal harmony and an overabundance of images and meanings, which makes translation difficult and restrictive.

- Ne'matollāh Wali (1329–1437) was probably one of the greatest mystical masters of his time. The order of dervishes he founded (The Order of the Nematollahis or Nimatullahi - Tariqa ) is still one of the most important of its kind in Iran . Born in Aleppo , Syria, he later moved to Samarqand , Herāt , Yazd and Kermān , where he also died. The city is still visited today by many pilgrims of Sufism .

- Nur od-Din 'Abd or-Rahmān Jāmi (1414–1492), one of the last Sufi poets of the classical era. He was born in Jām , in Khorāsān . After extensive theological and literary studies in Herāt and Samarqand, he joined the Sufi brotherhood of the Naqschbandi (s) , of which he became superior. At the same time he washighly valuedby the Timurid princes under whose rule he lived (especially the Hoseyn Bayqaras ). He was a very creative poet and left behind some prose writings (mystical essays and biographies of Sufis ) which he wrote in Persian and Arabic, three divans, five masna poems (which he held in the style of Nezāmis ), and a collection of prose anecdotes in the he plaited versein the style of the Golestān of Sa'di . His other role model was Hāfez. In spite of his constant efforts to follow his predecessors, Jami was not lacking in originality. His richness in style and his handling of the language made him one of the masters of Persian literature.

- Nezām od-Din Ali Schir Herāwi (Nawā'i) (1441–1501), Jāmi's pupil and a well-known poet at the court of the Timurids.

Illustrations of Attār's Bird Conversations (13th century)

Kalile o Demne , Rudaki , version from 1429

Illustrations of Jami's Rose Garden of the Pious , 1553.

Famous Indian style poets - post-classical period

- Amir Chosrau Dehlawi (1253–1325) son of afamily who emigratedfromBalkh, author of numerous works in poetry and prose, is considered the greatest Persian poet of the Indian style. In addition to his five Masnawis, he wrote several other works on the history of India.

- Hasān Dahlavi (1274–1337), Sa'di representative in Delhi

- Orfi-e Schirāzi (1555–1590), is one of the best representatives of the so-calledIndian school ofthe 16th century. He is considered an extraordinarily original poet, even if he is relatively unknown among Iranians. He leftIranat an early ageto settle at the court of theGrand Mogul Akbar IinLahore(1556–1605). He left a divan and twomasnawis.

- Faizi , also Feisi and Feyzi (1556–1605), born in Agra , India , spent his entire life at the court of the Grand Mogul Akbar, where he was a patron of Orfi . Great scholar that he was, he wrote a commentary on the Qur'an and made translations of Sanskrit into Persian . He also left behind some Ghazale ( Qawwali ), Qasids and several Masnawi seals .

- Tāleb-e Āmoli († 1626), born in Āmol , Mazandaran , lived in Kashan and Marw before he settled at the court of the Grand Mogul Jahāngir (1605–1627) in India, where he worked as a poet prince . He wrote a divan and the jahangirnam in an epic style.

- Sā'eb-e Tabrizi (1607–1670), born in Isfahan as the son of a merchant family of Tabriz origin, initially worked at the court of the Safavids before he went to the court of the great mogul Shah Jahān . Then he went to the court of Abbās' II (1633–1666), where he worked as a poet prince . He then went to India one more time before finally returning to Iran , where he stayed until the end of his life. It is little known among Iranians, but it is well respected in both India and Turkey . He can certainly be considered one of the most brilliant poets in post-classical literature.

- Mirzā Jalāl Asir (1619–1658) came from a family of Seyyeds from Esfahān under Abbās II. He wrote Qasids, fine and subtle Ghazals ( Qawwali ), Rubā'is and other poems. From the beginning of the 18th century, it was often imitated by lovers of the Indian style .

- Hakim Abdul Qāder-e Bidel Dehlawi (1645–1721), born in ʿAẓīmābād ( Bihar ), spent most of his life in solitude and freedom in Shah Jahān Ābād (the name of Delhi at that time), where he practiced mystical meditation and writing gave several works in prose and poetry. He wrote several masnawis and a divan with poetry of different genres. After Amir Chosrau he is considered the best representative of Persian poetry of the Indian style. In his works, subtle, mystical thoughts are combined with complicated terminology and images.

See also : Firuz Shah Tughluq

Famous Persian Poets of the Persian Style - Post-Classical Period

- Moschtāq (1689–1757), born and died in Esfahān, was one of the pioneers of the reaction against the Indian style . He himself made use of the so-called Iraqi style in his poems , which was characterized by a new choice of themes and expressions.

- ʿĀšeq (1699–1767) (Turkish spelling Aşık , short for ʿĀšeq Esfahāni, actually: Moḥammad Chan). Also from Isfahan, he campaigned for a return to the style of the 13th and 14th centuries.

- Āzar († 1780) lived in Chorāsān, Esfahān and Schirāz , where he also participated in the reaction movement against the Indian style . At the court of the successors of Nadir Shah and at the court of Karim Khan , he wrote panegyrics. He also wrote a collection of poems, Atasch Kade ( Fire Temple ), and a Romanesque epic, Yusof o Soleika (Joseph and Putiphar's wife) based on Jāmi's model.

- Hātef († 1783) (full-time doctor) had a decisive influence on the return to the classical style . He wrote excellent prose works and poems in both Persian and Arabic . He left behind a collection of qasids, ghazals and strophic poems (tardjiband (e)) , in an eloquent, clear and precise style.

- Medschmār († 1810) (actually Mojtahed-os-choara Seyyed Hoseyn Tabataba'i - called: Medschmār ), born in Isfahan, he came at a young age to Tehran where he met with the help of the poet Nechat at the court of Fath Ali Shah was introduced . He successfully and extremely eloquently imitated some of the ghazals of the poet Sa'di .

- Fath Ali Chān Sabā († 1822), official poet of Fath Ali Shāh. With him at the latest, the reaction movement reached its full bloom. He wrote several longer poems: one about the reign of Fath Ali Shāh, another about Mohammed and Ali , and a moral poem that he wrote in the style of Sa'di (Bustān) .

- Nechāt (1761-1828) (Mo'tamid od-Doule Mirzā Abd ol-Wahhab Nechāt), born in Esfahān, lived in Tehran from 1808, where he was state chancellor at the court of Fath Ali Shah. His calligraphy made him famous. He wrote letters in elegant prose, long Masnavia and lyrical poetry of great imagination and stylistic beauty (his ghazals are reminiscent of those of Hafiz ). His Qasids and Masnawis also approach those of the old masters. Occasionally, a preference for mysticism also becomes apparent in his poetry .

- Foroughi (1798–1857) (Mirzā Abbās Foroughi), born in Bastam, is one of the best Persian poets of the 19th century. First he wrote the panegyric of the Qajar rulers . In the course of the second half of the century he devoted himself more and more to mysticism and wrote a number of spiritually and stylistically impressive ghazals.

- Scheibāni (1825–1890) is one of the most important poets of the 19th century in Persian poetry. Scion of a military aristocratic family, he wrote the panegyric works for Mohammad Schāh , Nāser od-Din Schāh and his son. Later he turned more to mysticism and also wrote some prose writings. His poetry helped to simplify the style.

- Amiri (1860-1917) (Sādeq Chān-e Farahan, with the title Abibolmamalek (scribe of the empire) ) came from a family of writers. He knew several foreign languages of the Orient and the Occident . He took part in the Constitutional Revolution and took over some magazines during the rise of the press . He mastered almost all traditional forms of poetry, especially that of the Qasids, which he used above all to express his new ideas and his social criticism. His work shows the influence of European writers.

- Iradsch (1874–1926) (actually Iradsch Mirzā or Iraj Mirza (the Prince Mirzā) ) belonged to a younger line of the royal family. Exceptionally well educated (he mastered Arabic, Turkish, French and Russian ), he was the court's official poet for a while, but eventually he preferred a career as an official . Even if he did not participate in the political struggles of the time, he developed many new thoughts that reflected the influence of the Occident. He was also involved in the new women's movement . His poems, written in a simple style, also show a sense of humor. He is very popular among Iranians.

20th Century Persian Literature (Iran)

As early as the middle of the 19th century, the beginning of a new era in Persian literature followed by drastic changes in form and style. An example of this can be seen in an incident at the Qajar court of Nāser od-Din Shāh, in which the reform-oriented prime minister of the time, Amir Kabir , accused the poet Habibhollāh Qā'āni of " outright lying" when he was in a hymn of praise (panegyric) in the Qasid style praised. From then on, this form of poetry was regarded as inhibiting progress and contrary to modernization . Instead, more and more voices were voiced that viewed literature as the mouthpiece of social needs and change . This new tendency can only be seen in the context of the intellectual movement among the Iranian philosophers of the time in connection with the social changes that culminated in the Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911). Poets like Ali Akbar Dehchoda and Abu l-Qāsem Aref tried to do this poetically by introducing new content into Persian poetry and experimenting in the area of structure , rhetorical figures (see also list of rhetorical stylistic devices ) and lexicous semantics . Even if in connection with these changes it has often been argued that the concept of modernization should be equated with that of westernization , it can be argued that all the representatives of the new movement were certainly inspired by tendencies, especially in European literature, but not blindly copied, but adapted to the needs of the social and cultural reality in Iran. Sādeq Hedāyat's modernism, for example, expresses itself in a secular criticism of Iranian society - without any ideological determination - but in a reality-grasping and yet personal, subjective , very sensitive perception of the underprivileged and simple sections of the population in Iranian society, as is the case above all in can find his novellas.

Poetry

Persian modernism

- Mohammad Taqi Bahār (1886–1951), born in Mashhad , can be regarded as the greatest poet of Persian modernism . As a writer and as a politician, he took an active part in the revolutionary movement of his time. From 1916 he animated the Society for Literature Daneschkade , which had set itself the goal of writing "ancient verses with new thoughts". As a professor at the University of Tehran , he was one of those who contributed to the further development of literary history . He drew his inspiration from the life of his time - it was shaped politically, socially and morally. His spectrum of activity encompassed all lyrical forms, but especially those of the Qasids. He knew how to combine traditional elements harmoniously with elements of modern language (here archaisms with elements of everyday language (including dialects )). With his expansion of inspiration and means of expression, he exerted a great influence on 20th century poetry.

- Raschid Yasemi (1896–1951), born in Kermanshah . As a professor at the University of Tehran, he published studies on Persian philology and history (see also Iranian Studies ). He also translated works by French writers . As a poet, he campaigned for those who fought for a renewal of Persian poetry without abandoning traditional elements. His ideas move in the direction of modernity, his style, soft and melodic, reflects on the one hand the culture of the classical period and on the other hand the influence of French poetry.

- Parwin E'tesāmi (1906–1941) can be seen as the best poet of Persian modernism. As the daughter of an important poet, she dealt primarily with moral andsocialissues, which shetreatedemotionally in the classical form (inQasids,GhazalenandMasnawiform). Her style is light and clear, with moderate use of modern languageto animatetraditionalmetaphors.

The "New" Persian Poem - Sche'r-e Nou

- Nimā Yuschidsch (Nima Yushij) (1896–1960), is often referred to as thefather of the "New" Persian poetry. Born inYush, a village inMazandaran, in northernIran, Nimā Yushidsch grew up in the countryside, regularly helping his father with his work and occasionally camping around the campfire with the shepherds in the area. The simple but entertaining stories they told him there, including about conflicts within the village population, impressed him very much. After attending a religiously orientedmaktab(school), his parents sent himto a Catholic school inTehranwhen he was12 years old. One of his teachers there,Nezam Wafa, himself a well-known poet, discovered and promoted Yushidsch's poetic talent. The completely contradicting new life combined with the new teaching content, which did not correspond to his living environment, urged Nima in his poetry to search for new methods of representation in the processing of impressions. Initially connected to the tradition ofSa'diandHāfez, he broke away more and more from the old models until he broke completely new ground: the focus of the depiction was now on the "little man" in dealing with current problems. Here he made use of the natural, also locally colored everyday language, new schemes that allowed a free flow of thoughts - freed from the previously prescribedmeter. Alsorhymeandrhythmwere changed,personificationsused. Symbolismsfollowed structural integrity, whereby his poems could be read as a dialogue between several (2-3) symbolic references. Hāfez had already used such a technique, but on athematicratherthan asymboliclevel. Nima's poems did not reach the public until about 1930, but they marked a turning point in understanding the principles of traditional poetry that had a lasting impact on subsequent poetry.

- Forugh Farochzād (1935–1967) belonged to the first generation toadoptthe new style of poetry Nimās , which included increased experimentation with rhythm, images and the influence of the poet personality himself in poetry. She was the first poet to deal with sexual subjects from the personal and feminine point of view of the subject in her poems. In addition to poetry, she expanded her artistic work to include painting, acting and making documentaries .

- Another important representative of the New Poetry is Sohrāb Sepehri (1928–1980), poet and painter. His poems are characterized by a strong advocacy of humanistic values and a keen love of nature. He died prematurely of the consequences of his leukemia .

The White Poem - Sche'r-e Sepid

The Sepid poem (The White Poem) is a further development of the New Poem , which moved further away from the previous rules and restrictions of poetry and developed a freer structure. According to the poet Simin Behbahāni (1927–2014) Bijan Jalāl (* 1927 ) must be seen as the developer of this form of poetry, as it was only through his works that it gained general attention and recognition. Another equally important representative of this type of poetry is Ahmad Schāmlou (1925-2000), who reflected on the musicality and linguistic poetics of the words and processed them in a prose-like process without losing the poetic character. Simin Behbahāni herself rather devoted herself to the Chār Pare style Nimās , and then turned back to the Ghazal, which she decisively developed further by introducing topics of theater and everyday life in connection with everyday conversations into this form of poetry and expanding the scope of traditional Persian verse forms . Her works are among the most important in Persian literature of the 20th century.

Poems of bridging

In 1951, the poet Mehdi Achawān Sāles (1928–1990) brought out a literary magazine, Orgān , in which he published poems bridging the gap between the traditional Chorāsān style and Nimā's new style of poetry. He himself is one of the great poets of the 20th century who introduced free rhythms into a modern form of the epic. Also Fereydun Moschiri (1926-2000), who extended the geographical and social spectrum of Persian literature of the 20th century, can be classified in this direction. A middle position to Nimā , Schāmlou and Sāles takes Rezā Schafi'i-Kadkāni (* 1939) (a poet of the pre-revolution (1979)), whose works show influences from Hāfez and Jalal ad-Din ar-Rumi, at the same time inspired by the political Atmosphere of the time.

prose

At a writers' congress in 1946, the literary professor and writer Parviz Natel-Chanlari proclaimed the future of literature as the "age of prose", which at that time was considered a rather bold assertion given the extensive tradition in the genre of poetry. Even if poetry has by no means lost its important position in literary production and remains an important means of expression, literary development shows a decisive turn towards prose (cf. Ghanoonparvar , p. 1).

Since prose had embarked on this path in the early 1920s with the publication of Jamālzāde (1895-1997) anecdotal stories Yeki bud Yeki nabud [ Once upon a time] , it went through several phases, which were largely determined by the social and political conditions and circumstances of the time were shaped. Ghanoonpar on this: " Perhaps in no other country has the development of literature been so closely associated with social and political fluctuation as in Persia during the [present] 20th century ." (Gh, p.1) In his foreword to Yeki bud Yeki nabud Jamālzāde , who was still strongly inspired by the post-revolutionary (1905–1911) vigor of his time, formulated the quasi-manifesto of modern Persian literature, in which he pleaded for a “democratization of literature”. He saw the function of literature here, on the one hand, in educating the masses and , on the other hand, in retaining popular and socio-regionally varying ways of speaking .

The most influential figure in Persian prose of the 20th century, however, remains Sādeq Hedāyat (1903-1951), the jamālzāde in the 1930s in his interest in various aspects of Persian culture and language in his (Hedāyat) characteristic, very personal, philosophical, Sometimes a surreal and very pessimistic style followed (see above all Die blinde Eule (1937) [Owl: Symbol of Wisdom] ). The Persian literature of the 1940s was then characterized by an ostensible socio-political interest, which gave the artistic aspect a subordinate role. Among the most respected representatives of this period are Bozorg Alavi (1904-1997), who had been imprisoned for four years during the reign of Rezā Shāh Pahlavis because of his Marxist views, and Jalāl Āl-e Ahmad (1923-1969).

Bozorg Alavi had committed literature (see Sartre , Existentialism , but also the regulative function of the gaze in the Zoroastrian religion (Masani, (University of Bombay) Paris, Payot 1939, p. 60)) in the service of political ideology and the masses of the population prescribed. His work Tscheschm-ha-yasch (Your Eyes) (1952) can be seen as an example of this. He saw his role as a writer in providing intellectual guidance and as a mouthpiece for the masses. In terms of artistic development, however, the works of Sādeq Tschubak (1916–1998) from the period between the 1940s and 1960s occupy a leading position. His primary interest is formal aspects and linguistic skill in connection with an objective, impersonal worldview, and the associated possibility of literary experiment. In his short story collection Cheymehschab-bazi (Marionette Play) (1945) he carefully traces the life of individual representatives of the lowest social class, whereby he is particularly successful in translating their language into literary art. The literature of the following period takes up the suggestions from the previous developments by combining the formal and artistic possibilities with socially oriented content. Hushang Golschiri (1937–2000), who in his short novel Schahzade Ehtedschab (Prince Ehtedschab) (1968) uses the stream of consciousness technique and the inner monologue to trace the moral torment of the offspring of a tyrant dynasty, and a number of younger writers are exemplary , including authors such as Simin Dāneschwar , Moniru Rawānipur (* 1954) and Schahrnusch Pārsipur (* 1946), who produced some excellent novels , whereby the 1979 revolution resulted in an increased focus on political-Islamic topics. (Ghanoonparvar, pp. 1–7, Meyers Lexikon Online)

Persian poets in India (or Pakistan) (transition from 19th to 20th century)

- Iqbāl -i Lāhōrī (1877–1938), the last famous poet ofPersian onthe Indian continent. As a philosopher, he combined his traditional education with a strongly developed culture of the Occident, which he acquired during his training inCambridge(England) andMunich. In his works he expressed pan-Islamic thoughts and a renewed mysticism. In addition to thepoems and prose writteninUrdu(his native language), he published several assemblies in Persian, in which he expressed his powerful and original thinking in a style that combined the traditions of mystical poetry with Western influences.

Persian poet in Afghanistan (20th century)

At the beginning of the 20th century, Afghanistan was faced with major social and economic changes, which also required new approaches to literature. In 1911 , after several years of exile in Turkey, Mahmud Tarzi , who was influential in government circles , returned to Afghanistan, where he published a magazine called Sardsch'ul Achbar , which appeared every two weeks. Even if this magazine was not the first of its kind in the country, it was an important platform for change and modernization in the fields of journalism and literature. In the field of poetry and lyric poetry, it opened the way for new forms of expression, which on the one hand gave the poet's personality more space to express their personal thoughts, while at the same time being strongly socially oriented. After months of cultural stagnation in 1930 (1309), a group of writers founded the Herats literary circle in the country's capital, which was followed a year later by the Kabul literary circle . Both circles published their own magazine on the subjects of culture and literature, although they hardly managed to bring about further literary innovations. Above all, the literary magazine of Kabuls devoted itself increasingly to traditional poetry instead. Prominent personalities of the time were Ghary Abdullah , Abdul Hagh Beytat and Chalilullah Chalili , the former two receiving the title Malek ul Shoarā (King of Poets) . Chalili, the youngest among them, represented the traditional Chorāsān style in contrast to the otherwise represented Indian style . His interest was also in modern poetry, to which he also contributed through new ideas and aspects of meaning . When the poems Gharāb and Ghāghnu by Nimā Yuschidsch were published in 1934 (1313) , Chalil also wrote one in his rhyme scheme, Sorud-e Chusestān (song, hymn of Chusestan) and sent it for publication to Kabul, where it was used by the traditionalists Was rejected. Despite all the initial difficulties, the new styles gradually found their way into literature and the public. In 1957 (1337) the first volume with new poems was published and in 1962 (1341) another collection in Kabul. The first group of poets to represent the new style included Mahmud Farāni , Baregh Shafi'i , Suleiman Laeq , Qahare Ahssi, Schabgier Poladian, Nadja Fazzel, Soheil Āyeneh and a few others. Later, others such as Wāsef Bachtāri , Asadullah Habib and Latif Nāzemi joined, each with their own contribution to the modernization of poetry in Afghanistan. Other important personalities are Usatd Behtāb , Leilā Sarāhat Roschani , Sayed Elān Bahār , Raziq Faani and Parwin Pāzwāk . Poets like Mayakovsky , Yase Nien and Lāhuti (an Iranian poet who lived in exile in Russia) exerted influence on the Persian poets of Afghanistan. The influence of Iranian poets such as Farokhzād, Yazdi and Schāmlou was particularly noticeable in the second half of the 20th century. For Afghan prose, please see the web link with an informative article by Monika Pappenfuß.

Persian poet in Tajikistan (20th century)

The more recent poetry of Tajikistan deals with the living conditions of its inhabitants and the effects of the revolution. Until the emergence of modern poetry in France, Asia and Latin America, there was a strong urge for renewal, with the poetry of Muhammad Iqbāl Lāhori and that of modern Iranian poets clearly serving as role models. The 1960s proved to be a particularly creative and active creative period in the poetry of Tajikistan, especially in terms of theme development and literary form. However, only a few writers broke away from the strong external influence in literature, especially European literature, which was often only imitated and did not lead to a form of its own. The best-known representatives of Tajik literature include Golrochsar Sāfijewa , member of the PEN Club of Tajikistan, Mo'men Ghena'at , Farzāne Chodschandi , Lājeq Scher Ali , Abied Radschāb , the u. a. was awarded the Rudaki Prize, and Abolqasem Lāhuti .

Important literary genres of New Persian (overview)

-

Epic

-

Epic romance novel / courtly novel (verse novel) such as

Bidschan and Manidsche (1312 verses in Shāhnāme ( Ferdousi )), Sorch But and Chonak But and Wameq and Asra of the poet at the court of the Ghaznavids ( Onsuri ), Warqa and Golschāh ( Ayyuqi ), Wis and Ramin ( Gorgani ) Chosrau and Schirin and Leila and Madschnun ( Nezami , Amir Chosrau Dahlawi , Dschami ). Also Siāh Mu and Jalāli , written by the poet Siāh Mu Herāwi (from Herāt ), Joseph and Soleyka (Putiphar's wife) (Āzar) - Epic hero poem z. B. Shāhnāme (Ferdousi), Garchaspnāme (Āzādi), Eskandarnāme ( Nezāmi ), Tughluqnāme (Amir Chusro Dahlawi), Jahāngirnāme (Tāleb-e Āmoli), (Mahdi Achawān Sāles)

- Nāme ( literally "letter" - here : treatise (also theogony and cosmogony in verse form )): Āfarinnāme (Abu Shakor), Nouruzn āme ( Omar Chayyām ), Sharafnāme and Gandschawi as well as Monādschātnāme (Ansari), Ochāqnāme (

-

Epic romance novel / courtly novel (verse novel) such as

-

Poetry (Nazm)

- Nazm ( poetry ) : Rudaki , Sanā'i, Nezāmi , Attār, Erāqi, Wali, (Asir Indian style ), Āzar, Hātef, Sabā, Nechāt, Scheibāni, Iradsch, Eqbāl , Rachid, Zabihollah Safā , Abbās Kiārostami

- Qassida (Qasida) : Rudaki, Ayyuqi , Moezzi, Anwari, (Faizi, Asir ( Indian style) ), Hātef, Nechāt, Amiri, Bahār, Parwin E'tesāmi

- Ghazal : Representatives of this genus are Rudaki, Ayyuqi , Farrochi , Moezzi, Forughi, Anwari, Sa'di , Omar Chayyām , Jalal ad-Din ar-Rumi , Hāfez , Hātef, Medschmār , Parwin E'tesāmi , Simin Behbahāni

- Masnawi : Rudaki , Sanā'i, Nezāmi , Fariduddin Attār , Erāqi, Jalal ad-Din ar-Rumi; (a divan from Rumi is called: Masnawi-e Manawi (witty double verses) or Mesnevi ), Amir Chosrau (Indian style) , Dschāmi , Orfi (Indian style) , Bedel ( Indian style) , Nechāt, Parwin E'tesāmi

- Rubāʿi ( quatrains ) : representatives of this genus are Rudaki , Bābā Tāher , Omar Chayyām , Jalal ad-Din ar-Rumi, (Asir Indian style )

- Hamd ( panegyries (songs of praise)) : Rudaki, Daqiqi , Farrochi , Āzādi, Anwari (one of the most valued panegyric writers of the Persian language) , Modschir, Hāfez , Āzar, Foroughi, Scheibāni

- Mosammat (strophic poetry) : Manutschihri

- Tardjiband (strophic poetry) : Hātef

- Tasnif : melodic ballad

- Sche'r-e Nou (The “New” Persian Poem) : Nimā Yuschidsch , Forugh Farochzād , Simin Behbahāni , Sohrāb Sepehri

- She'r-e Sepid (The White Poem) : Bidschan Jalāl , Ahmad Shāmlu , possibly Golschiri , Taraneh Dschawanbacht

- Poems for building bridges : Mahdi Achawān Sāles, Fereydun Moschiri, Rezā Schafi'i-Kadkāni

-

Poetry , Sabke Hendi (Indian style, with and without music, see also under 2.)

- Tarāne (song)

- Naqsch o Gol (literally pattern and flower) : Amir Chosrau Dahlawi

- seam

- Qawwali : Faizi, Asir

- Rak or raga : Rak-e Chiāl (dream raga) and Rak-e Jalāli (ecstasy raga)

-

Prose (nasr)

- Fakā-i anecdote : Sa'di , Jāmi

- Short story :Jamālzāde, Golschiri, Ahmad Mahmud, Jamāl Mirzādeghi,Jawād Modschabi, Ja'far Modarres-Sādeghi,Shahrnush Pārsipur

- Novella : Sādeq Tschubak,Sādeq Hedāyat,Jamālzāde

- Drama : Sādeq Tschubak,Sādeq Hedāyat, Jawād Modschabi

- Script / Screenplay :Bahman Ghobadi,Abbās Kiārostami,Mohsen Machmalbāf,Samirā Machmalbāf,MajidMadschidi, Jawād Modschabi, Gholām Hoseyn Sāedi

- Dāstān (literally from "Da (m)" and "stān" "wild" garden) Fable : Samad Behrangi , Ahmad Mahmud

- Afsāne (derived from “Afsun”, “dreamy”) Fairy tales : A thousand and one nights , a thousand and one days , Samad Behrangi

- Hekayat : narrative : Executive Abdolah , Jalal Ahmad, Bozorg Alavi , Sadiq Tschubak, Mahmud Doulatabadi, Nader Ebrahimi, amine Faghiri, Golschiri, Dschamālzāde , Taraneh Dschawanbacht , Mahmud Kiānusch, Ahmad Mahmud, Ja'far Modarres-Sadeghi, Gholam Hoseyn Saedi, Fereydun Tonekaboni, Asghar Elāhi,

- Novel :Kader Abdolah, Ali Mohammad Afghāni, Bozorg Alavi, Rezā Barāheni, Sādeq Tschubak,Simin Dāneschwar, Ebrāhim Golestān, Golschiri,Sādeq Hedāyat, Ahmad Mahmud, Dschamāl Mirzādeghi,Piraud'l Sādurādipur, Pirādādipur, Pirāneschwar , Gholām Hoseyn Sāedi

- Satire : Bibi Chatton Astarābādi, Dehchodā, Kioumars Sāberi Fumani, Hādi Chorsandi, Jawād Modschabi,Iradsch Mirzā, Ebrāhim Nabāwi, Omrān Sālehi, Obeyd Zakāni

- Treatise :Nāser Chosrou,Omar Chayyām, Jalal ad-Din ar-Rumi, Erāqi,Mohammad Chātami,Seyyed Hoseyn Nasr,Ali Schariati,Abdolkarim Sorusch

- Essay :Nezām al-Mulk,Sa'di,Jāmi, Jawād Modschabi,Abdolkarim Sorusch,Chosrou Nāghed

- Monāzer ( debate ) : Āsādi

- Columns :Kader Abdolah, Ja'far Modarres-Sādeghi

- Documentation :Schirin Ebādi

- Biography : Attār,Jāmi

- Epistle :Omar Chayyām

- Letters (div. Forms): Siyāsatnāme (Nizam al-Mulk) Safarnāme (Naser Khosrow) Nechat,Abd ol-Karim Sorousch,Dārābname-ye bigami, Firuznāme ,Dārābnāme-ye Tarsusi, Bachtiārnāme , Dschaschnnāme-ye EBN e siNA ,Dalirān-e Dschānbāz (English: 'The Warriors)s. Ciyarids

- Further

swell

- Zabihollah Safa: Anthologie de la Poésie Persane (= UNESCO collection of representative works ). Gallimard Unesco. Connaissance de l'Orient, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-07-071168-4 (first edition: 1964).

- Iraj Bashiri : Nima Youshij and New Persian Poetry . University of Minnesota (USA) 2000.

- MR Ghanoonparvar (University of Texas): An Introduction to "Reading Chubak" . Iran Heritage Organization, 2005.

- Alamgir Hashmi: The Worlds of Muslim Imagination . Gulmohar, Islamabad 1986, ISBN 0-00-500407-1 .

literature

- Literary stories ( etc. )

- Bozorg Alavi : History and Development of Modern Persian Literature . Berlin (formerly East) 1964.

- Mohammad Hossein Allafi : A Window to Freedom. 100 years of modern Iranian literature - 3 generations of authors . Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 978-3-930761-23-4 .

- Edward G. Browne : Literary History of Persia . 1998, ISBN 0-7007-0406-X .

- Alamgir Hashmi: The Worlds of Muslim Imagination . Gulmohar, Islamabad 1986, ISBN 0-00-500407-1 .

- Paul Horn: History of Persian Literature . CF Amelang, Leipzig 1901. (= The literature of the East in individual representations , VI.1) Reprint Elibron Classics, 2005, 228 pages, ISBN 0-543-99225-X

- Henry Massé: Anthology Persane . Payot, Paris 2004, ISBN 2-228-89128-2 (first edition: 1950).

- G. Morrison, et al .: History of Persian Literature from the Beginning of the Islamic Period to the Present Day . 1981.

- Jan Rypka , Robert Salek, Helena Turkova, Heinrich FJ Junker: Iranian literary history . Leipzig 1959.

- Zabihollah Safa : Hamāse-sarā'i dar Irān (story of the heroic epic in Iran) . Tehran 2000 (first edition: 1945).

- Zabihollah Safa: Tārikhe Adabiyyāt dar Irān (History of Literature in Iran) . tape 1 -8 (1953 ff.). Tehran 2001.

- Zabihollah Safa: Tārikh-e Tahawol-e Nazm-o-Nasr-e Pārsi (history of development of personal poetry and prose) . Tehran 1974 (first edition: 1952).

- Zabihollah Safa: Un aperçu sur l'évolution de la pensée à travers la poésie persane . Tehran 1969.

- Kamran Talatoff: The politics of writing in Iran. A history of modern Persian literature . Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, NY 2000.

- Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): History of Persian Literature . New York, NY (since 1988).

- Anthologies and editions of works

Poetry

- Cyrus Atabay : The Most Beautiful Poems from Classical Persia. Hafez, Rumi, Omar Khayyam . 2nd Edition. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-44016-9 .

- Dieter Bellmann (ed.): The rose garden [Sa'di] . Carl Schünemann Verlag, Bremen 1982 (translations by Karl Heinrich Graf).

- Ernst Bertram : Persian proverbs (= Insel-Bücherei . No. 87 ). Insel-Verlag, Leipzig and Wiesbaden branch in 1944 (and 1949).

- Hans Bethge: Sa'di the Wise. The songs and sayings of the Sa'di. Re-seals . Yin Yang Media Verlag, Kelkheim 2001, ISBN 3-9806799-6-9 .

- Dick Davis: Borrowed Ware. Medieval Persian Epigrams . Mage Publishers, Washington DC 1998, ISBN 0-934211-52-3 .

- Volkmar Enderlein , W. Sundermann: Schâhnâme. The Persian Book of Kings. Miniatures and texts from the Berlin manuscript from 1605 . Hanau 1988, ISBN 3-7833-8815-5 .

- Edward Fitzgerald: Omar Khayyam. Rubaiyat . ISBN 3-922825-49-4 .

- Joseph von Hammer : Hafis: The Divan. Reprint of the edition from 1812/13 . tape 1-2 . YinYang Media Verlag, Kelkheim 1999, ISBN 3-9806799-3-4 .

- Khosro Naghed (Ed.): Omar Khayyam: Like water in a stream, like desert wind. Poems of a mystic . Edition Orient, Meerbusch 1992, ISBN 3-922825-49-4 (Persian, German, translation: Walter von der Porten).

- Mahmud Kianush: Modern Persian Poetry . The Rockingham Press 1996, Ware, Hertz, England UK 1996.

- Friedrich Rückert : Firdosi's Book of Kings (Schahname) Sage I – XIII . epubli GmbH, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86931-356-6 .

- Zabihollah Safa: Anthologie de la Poésie Persane . Gallimard Unesco. Connaissance de l'Orient, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-07-071168-4 (first edition: 1964).

- Zabihollah Safâ: Gandje Sokhan . Poetry (= treasure chest of poetry . Volume 1-3 [1960-1961] ). Tehran 1995.

- Kurt Scharf (Ed.): The wind will kidnap us. Modern Persian poetry . With an afterword by Said (= New Oriental Library ). CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-52813-9 .

- the same: I still think of that raven. Poetry from Iran. Translated and selected by Kurt Scharf, Radius-Verlag, Stuttgart 1981.

- the same: "Bear no longer the silence on your lips, you country!" To contemporary Persian poetry. die horen 26, 1981, 2, pp. 9–32 (with short biographies: pp. 163–169) ISSN 0018-4942 .

- Annemarie Schimmel (Ed.): Attar . Bird talks and other classic texts presented by Annemarie Schimmel. CH Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-44881-X .

- Annemarie Schimmel (Ed.): Friedrich Rückert (1788–1866) Translations of Persian poetry . Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1966.

- Annemarie Schimmel: Rumi: I am the wind and you are fire. Life and work of the mystic . Diederichs, Cologne 2003 (first edition: 1978).

- Annemarie Schimmel: Look! This is love Poems. Rumi . Sphinx, Basel 1993.

- Wheeler M. Thackson: A Millennium of Classical Persian Poetry: A Guide to the Reading & Understanding of Persian Poetry from the Tenth to the Twentieth Century . Ibex Publishers, Harvard, Cambridge, MA. 1994, ISBN 0-936347-50-3 .

- Gerrit Wustmann (Ed.): Here is Iran! Persian poetry in German-speaking countries . Subject, Bremen 2011.

prose

- Bozorg Alavi: Your eyes . Henschel, 1959.

- F. R. C. Bagley (Ed.): Sadeq Chubak: An Anthology . Caravan Books, 1982, ISBN 0-88206-048-1 .

- F. Behzad, J. C. Bürgel, G. Herrmann: Iran (Modern storytellers of the world) . Tuebingen 1978.

- JC Bürgel (translator): Nizami: Chosrou and Schirin . 1980 (personal poetry - novel in verse).

- Arthur Christensen , ed .: Persian fairy tales. Series: Diederich's fairy tales of world literature. Last edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1998

- Mahmoud Dowlatabadi : Kelidar . Unionsverlag, Zurich 1999 ISBN 3-293-20145-8

- Mahmoud Dowlatabadi: The empty place of Ssolutsch , Unionsverlag, Zurich 1996 ISBN 3-293-20081-8

- Mahmoud Dowlatabadi: The Journey . Unionsverlag, Zurich 1999 ISBN 3-293-20139-3

- Sadeq Hedayat (transl. Bahman Nirumand ): The blind owl. Novel . Library Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1997.

- Inge Hoepfner (Ed.): Fairy tales from Persia . Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 3-596-22838-7 .

- Khaled Hosseini : Kite Runner . Berliner Taschenbuch Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 978-3-8333-0149-0 .

- Khaled Hosseini : A thousand radiant suns . Bloomsbury, Berlin 2007 ISBN 978-3-8270-0671-4

- Heshmat Moayyad: MA Jamalzadeh: Once Upon A Time . Bibliotheca Persica, 1985.

- Heshmat Moayyad (Ed.): Stories from Iran. A Chicago Anthology . Mage Publishers, Washington, DC 1992, ISBN 0-934211-33-7 .

- Seyfeddin Najmabadi, Siegfried Weber (ed., Translation): Nasrollah Monschi: Kalila and Dimna. Fables from Classical Persia . CH Beck, Munich 1996.

- Hushang Golschiri: Prince Ehteschab . CH Beck, 2001.

- Jamalzadeh: Yeki Bud Yeki Nabud (collection of 6 short stories) . Berlin 1921.

- Touradj Rahnema (ed.): One from Gilan. Critical stories from Persia . Edition Orient, Berlin (formerly West) 1984, ISBN 3-922825-18-4 .

- Zabihollah Safâ: Gandjine-je Sokhan (Small Treasure Chest) (prose) . tape 1-6 . Tehran 1983 (first edition: 1969).

Old Persian literature

- Ulrich Hannemann (Ed.): The Zend-Avesta. Weißensee-Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 3-89998-199-5 .

- Reference work on Iranian studies

- Ehsan Yarshater et al .: Encyclopaedia Iranica . Costa Mesa (since 1985).

See also

Web links

- Persian collection of poems (Hafes, Saadi, Chayyam, Rumi etc.) (with translations into German)

- Various articles on Persian literature with works by Ferdousi, Saadi, Chayyam, Rumi, Hedayat (English)

- Hafez poems from the Gutenberg project

- 20th century poets with poetry examples (Iran) (Persian) ( Memento from February 3, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- Summary of the introduction to Modern Persian Poetry with poetry examples ( Memento from October 25, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- Modern Persian poetry ( Memento from June 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) essay by Khosro Naghed .

- Author link on Persian prose of the 20th century (Iran )

- Link to the Persian short story (Iran )

- Nine poems by nine contemporary Iranian poets (audio - German translation)

- Link to the Persian novel (Iran) (English)

- Shahnameh in Persian ( memento from November 26, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- Link to modern literature in Afghanistan (prose), which was mainly published in Pashto (German) s. a. Pashtun language

- Link with modern Afghan poetry (Persian) ( Memento from November 14, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Link with Afghan poetry (English)

- Homepage of the Encyclopædia Iranica

Remarks

- ↑ Hermann Ethe: Avicenna as a Persian poet. In: News from the Royal Society of Sciences and the Georg August University. Göttingen 1875, pp. 555-567.