Stone bridge

Coordinates: 49 ° 1 '22 " N , 12 ° 5' 50" E

| Stone bridge | ||

|---|---|---|

|

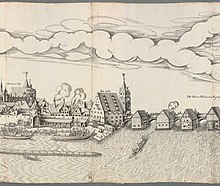

Stone bridge, view from the south bank of the Danube east of the bridge |

||

| use | Pedestrians and cyclists | |

| Crossing of | Danube | |

| place | regensburg | |

| construction | Stone arch bridge | |

| overall length | 336 m, of which 309 m are visible | |

| width | 8 m | |

| Number of openings | 16, of which 14 are visible | |

| Clear width | up to 16.70 m | |

| height | approx. 15 m (foundation carriageway) | |

| start of building | 1135 | |

| completion | 1146 | |

| location | ||

|

|

||

The Stone Bridge is next to the Regensburg Cathedral, the most significant landmark of Regensburg . When construction began in 1135, the Stone Bridge is considered a masterpiece of medieval architecture and the oldest preserved bridge in Germany.

After it was built, the Stone Bridge became the only bridge over the Danube between Ulm and Vienna , which gained great importance as a convenient connection between long-distance trade routes from the south and sales areas in the north. Regensburg as a transhipment point not only benefited from the customs income from long-distance trade, trade with the northern surrounding area was also made immensely easier. For 800 years, the bridge remained the only bridge to cross both arms of the Danube . The Nibelungen Bridge, built in 1938, was the second bridge that also crossed both branches of the Danube.

In the 20th century, the stone bridge was badly damaged mainly by salt ingress in the absence of sealing and by the loads of increasing heavy traffic (trams and articulated buses). The existing bridge turned out to be endangered and from 2010 to 2018 the pillars of the bridge, the corrugations and parapets were extensively renovated or renewed. The roadway was sealed and equipped with a new surface and new parapet. After the renovation, the Stone Bridge will connect the old town of Regensburg with the Stadtamhof district on the northern side of the Danube, within walking distance and free from car traffic . The bridge also crosses two arms of the Danube and between the two arms of the river a water-draining former Mühlkanal that branches off about 200 m upstream from the southern arm of the river.

description

The stone bridge is a natural stone vault bridge with 16 segment arches , of which only 14 can be seen. The first arch and the first pillar on the south side of the bridge were completely installed under the ground west of the bridge after 1551 in the course of the new urban construction of the first Bavarian Amberger Salzstadel, which was built by the Bavarian duke after 1485 and then demolished . However, the pillars and arches have been preserved under the bridge driveway and as the foundation of the bridge tower - as was shown in 1989 during excavations on the occasion of the renovation of the urban salt barn, built between 1616 and 1620, to the east of the bridge. Until the end of the 15th century, as long as the first Bavarian salt barn existed, the Wiedfangkanal flowed through the first arch. It led to the neighboring, medieval port on the Wiedfang to the west, which, like the canal, was then abandoned, so that after 1551 the better-founded new urban Amberg salt barn could be built there. The 16th arch on the north side of the bridge is almost completely covered by the Stadtamhofer Bridge Bazaar, as the northern approach to the bridge is called.

The bridge is not built in a straight line, but curved slightly to the east. It follows the ground conditions, takes the course of the flow into account, rises towards the middle and overcomes a height of 5.50 m. The pillars are unevenly thick and aligned differently. The bridge vaults are also different. The span of the 5.80 m to 7.60 m wide vaults vary between 10.20.80 m and 16.20 m.

With the first 5 arches - seen from the old town - the bridge spans the southern arm of the Danube. The 5th bridge pillar stands on the so-called Hammerbeschlächt , a dam built in 1388 as a hydraulic structure, which connects the western end of the Danube island Unterer Wöhrd with the eastern end of the island Oberer Wöhrd at a former mill location. With the arches 6 to 8 the bridge crosses the mill canal, the drainage basin of the former water-powered mills. Under the subsequent arches 9 and 10 there is a green area that usually remains dry and is only flooded when there is high water. From pillar 10 - the former location of the central tower - a ramp has been leading down westwards from the bridge to Oberen Wöhrd since 1499. The ramp used to be made of wood and was often destroyed by floods or ice.

Arches 11, 12 and 13 bridge the northern arm of the Danube. A partially unpaved, but accessible riverside path runs under arch 14 on the north arm upstream to Pfaffensteiner Steg, which connects the Upper Wöhrd with the suburb of Stadtamhof.

At the top of the bridge is the Bruckmandl (little bridge man), which once symbolized the city's civil liberties and the emancipation from the guardianship of the bishop. This figure was originally from 1446, the current version was erected on April 23, 1854. A previous figure is in the Regensburg Historical Museum .

Of the former three towers on the bridge, only the bridge tower from the end of the 13th century on the south side has been preserved.

Technical details

The bridge, which used to be 336 m long and is now 308.71 m long, now has no sidewalks after the renovation and is between 7.51 and 7.60 m wide, 18 cm of which is accounted for by the parapet walls.

The pillars were founded on oak gratings and consist of blocks made of Regensburg green sandstone and Danube limestone, which are backfilled with quarry stones. To this end, a cofferdam was built from oak piles and the area inside the dam was pumped out. It is said that the water level of the Danube was particularly low at the time of construction due to a drought.

To protect against scouring and erosion, the pillars are surrounded by tapering, artificial islands, which are called " slaughtered " here. For this purpose, rows of piles were rammed into the ground and backfilled with stone rubble, which was finally provided with a heavy masonry ceiling. In addition, both sides of the pillars were provided with triangular, brick, and different high pillars. On the Beschlächten were boulders stored as further protection against the current. Whenever the slaughtered areas were damaged by floods, new rows of stakes were put in front of them, so that over time the slaughtered areas became so large and unequal that water-powered mills and hammer mills could be built on them, although these were often damaged during floods. Only in the period between 1951 and 1963 were the slaughtered areas significantly reduced in size and protected by sheet piling.

With a total of 93.55 m, the cross-section of the piers already takes up almost a third of the length of the bridge. The current flow width is reduced to 122.5 m due to the fouling. This considerable constriction for the water flowing through creates a level difference of around 0.5 m between the upper and lower water of the bridge, a strong current under the bridge arches and water eddies below the bridge. Nevertheless, the stone bridge survived all the floods in its history , including the Magdalen flood of 1342, the flood of 1501 and also the flood of 1784 , which, however, severely damaged it.

history

Presumably, the Celts and Romans were able to cross the river at this point . Charlemagne had a ship bridge built in 792 , according to other sources a wooden bridge, but it did not last long because "the current and weather kept tearing the construction away". The construction of a stone bridge began in the extremely dry summer of 1135. The work under a no longer known master builder lasted until 1146. The clients were probably Regensburg merchants supported by the Bavarian Duke Heinrich the proud . At that time Regensburg was one of the wealthiest and most populous cities in Germany. The construction of the bridge towers for the southern and central towers can only be roughly dated to the period from the middle of the 13th to the middle of the 14th century, when the city fortifications were built. For the northern tower, the first target of a potential enemy, archaeological investigations have shown that it was built in 1246. In 1147 Konrad III broke . in Regensburg on the second crusade , the strategically favorable Danube crossing may have been the decisive factor. In May 1189, Emperor Friedrich I Barbarossa set out from there with a large force on the third crusade . Emperor Friedrich I Barbarossa had granted the bridge special privileges in 1182 (freedom of access to the bridge and freedom from customs duties); a bridge master's office was set up, which had its own rights and income and whose bridge master carried a bridge seal with the inscription: SIGULUM GLORIOSI PONTIS RATIPONE (seal of the glorious bridge of Regensburg) . The revenue from the bridge toll served to maintain it.

After Regensburg had become a Free Imperial City in 1245 , the state border between the city and the Duchy of Bavaria (later the Electorate ) lay north of the bridge bazaar and hospital area .

Between 1499 and 1502 a wooden bridge to the Upper Wöhrd was built.

During the Thirty Years War , when the Swedes advanced in 1633, the fourth (today the third still visible) bridge yoke was blown up and replaced by a wooden drawbridge after the end of the fighting. This makeshift condition remained until 1791. The southern bridge tower and the middle tower also burned out during the fighting for Regensburg (1632–1634) and were only restored after the end of the war in 1648.

In 1732 the roadway of the Stone Bridge was widened by replacing the original thick side parapets with thinner sandstone slabs. The ice rush connected with the catastrophic flood of February 1784 destroyed all the mills, grinding, polishing and hammer mills that had set up on the Beschlächten, and damaged the central tower so badly that it had to be demolished.

When the city occupied by Austrian troops was recaptured by French and Bavarian troops in 1809, the northern bridge tower, known as the Black Tower , was badly damaged in the course of the battle of Regensburg and was demolished a year later.

A traffic census in 1876 showed that an average of 22,138 people and 664 wagons used the bridge to cross the Danube every day. As a result, the sandstone parapet slabs were replaced by granite slabs from Flossenbürg in 1877 ; At the same time, the wooden connecting ramp to the Upper Wöhrd from 1502 was replaced by an iron structure.

By 1900 the Danube had developed into a major shipping route and municipal and state authorities began to view the Stone Bridge as a traffic obstacle. They expressed the intention "to consider the complete removal of the stone bridge" . This resulted in heated discussions among the population. When, in the course of the First World War, a continuous waterway for grain transport became increasingly important, the Rhein-Main-Donau-AG made the decision to bypass the bridge through a canal in the flood basin of the Danube north of Stadtamhof in order to avoid further disputes over the years (Protzenweiher) to be considered. These plans were only realized 70 years later with the construction of the Main-Danube Canal .

When the routing of the Regensburg tram lines was planned at the beginning of the 20th century and a line was supposed to lead over the bridge to Stadtamhof, the narrow access to the bridge through the 3 m wide pointed arched gate in the bridge tower proved to be an insurmountable obstacle. An extended driveway had to be created. This could only be achieved when two adjacent houses on the western side of the bridge tower - including the bridge toll house - were demolished and the resulting gap was spanned by an additional archway. To widen the carriageway after passing through the new gate, the bridge had to be widened a little. The construction work was completed in 1902 and did not adversely affect the appearance of the bridge access.

A few weeks before the end of World War II , on 22/23. April 1945, by order of the Gauleiter Ludwig Ruckdeschel, the first and the tenth pillar of the bridge were blown up in order to delay the advance of the Americans. The demolition led to the collapse of four arches of the bridge, the two city-side arches (I) and (II) and the arches (IX) and (X). The temporary wooden emergency bridges were not removed until 1967 and the vaults were rebuilt. The green sandstone blocks served as permanent formwork for the reconstruction of the arches in reinforced concrete .

In the course of repair work from 1950, the bridge was given parapets made of concrete slabs. In 1958, in order to comply with an American decree, two explosive chambers were built into each of the four pillars 3-6, which considerably weakened the structure of the pillars. The military-historical significance of these installations meant that these explosive chambers were entered in the list of monuments. The Beschlächte was built back to its present size by 1962 and steel sheet piling and solid concrete structures were built around the pillars to protect against undercutting. 1958

The figure of Bruckmandl lost her right arm in an unexplained manner on the night of December 27, 2012, whereupon the city of Regensburg filed a complaint against unknown persons. As part of the fourth construction phase of the bridge renovation (see below), the figure received a second arm in summer 2016, but it was only put back up after the renovation was completed [out of date] .

State of construction and renovation after 2010

Due to the heavy traffic of the past decades and especially the lack of sealing of the roadway and the application of road salt, the stone substance of the bridge was deeply damaged right into the interior of the piers and the long-term existence of the bridge was endangered. After a referendum, the bridge had been closed to private car traffic since 1997. On the evening of August 1, 2008, buses and taxis were also closed. The reason for this measure, which was surprising at the time, was an expert opinion that the bridge parapets would not withstand the impact of a bus.

The bridge was renovated from 2010 to 2018. For the long-foreseeable renovation, preliminary investigations had been carried out since 1993, such as measurements , hydrographic measurements , hydraulic loads , load-bearing behavior , effects of temperature, ice drift, wind and flood, various stone laboratory tests, structural analysis and, in particular, the clarification of the future appropriate payloads . The results showed that the stresses caused by the articulated bus, which was permitted until 2008, were higher than the stresses caused by the former tram that operated on the bridge until 1945. Overall, it turned out that the major damage to the bridge only occurred in the last 100 years of the almost 900-year service life of the bridge. In addition, there were estimates of the effects of serious damage to the bridge in the past, such as B. the installation of the explosive chambers in four pillars. The requirements for the planning and construction of the trade were also very high , because the bridge was supposed to continue to function as a bridge between the old town and Stadtamhof during the long construction period. For this purpose, steel bypass walkways had to be built to the side of the respective construction section. In addition, despite massive interventions to renew the entire superstructure, the bridge should retain its high monument character, a topic that may be taken up in a very emotional and polarizing way by the public, who like to orient themselves towards the familiar. After completion of the renovation in Regensburg, the new bridge paving was rejected on a massive scale because the sidewalks and the familiar cobblestones were no longer there.

In the run-up to the renovation, an intensive search for suitable stone material began in 2009. It should match the original material in terms of color and structure and also have sufficient strength and weather resistance. They finally found what they were looking for in an abandoned quarry near Ihrlerstein (see also Ihrlersteiner Grünsandstein ). However, the plans to reactivate this quarry were rejected because the reopening of the quarry with the required purchase volume for the stone bridge could not be justified economically. Instead, stones were used that were stored in the city's construction yard and came from the demolition of a railway bridge. The criticism of the poor quality of the green sand stones provided by the general curator and head of the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation Egon Greipl was averted by developing a complex stone management process. The quality of each stone was determined and each stone was installed at a suitable point on the bridge according to its compressive strength. A lot of effort was required to prepare a mortar with special additives , which was required for the grouting given the high degree of salinity of the stones in the bridge.

In February 2013, the city of Regensburg announced that the company that had been commissioned with the first phase of construction was due to be repeatedly exceeded. The renovation of the bridge was originally supposed to be completed at the end of 2014, but was delayed until 2018. The bridge was only opened on June 10, 2018 as part of the UNESCO World Heritage Day in Regensburg.

After the renovation work has been completed, the bridge will no longer be opened to motorized traffic. That is why in the city of Regensburg there are always discussions about alternative bridge routes with which the residents of the western and northern district of Regensburg but also residents of the suburbs of the city north of the Danube cross the Danube without using the two existing motorway routes and that Can reach urban area. Two of the desired routes would make it necessary to build bridges upstream of the Stone Bridge.

City legend

A well-known legend about the construction of the Stone Bridge reads: The bridge builder made a bet with the cathedral builder as to who would be the first to complete his structure. After the cathedral was built much faster, the bridge builder made a pact with the devil, who wanted to stand by him when he got the first three souls to cross the bridge. From now on the bridge construction proceeded very quickly, so that the bridge was completed first. The devil was now demanding his wages, which is why the bridge builder had a rooster, hen and dog chased across the bridge at the opening. In anger about it, the devil tried in vain to destroy the bridge. Therefore, according to the legend, the bridge has a hump. In fact, the bridge was long since the construction of the cathedral began in 1273.

Songs

The folk song When we were recently in Regensburg, we drove over the strudel ... does not refer to the Danube strudel in Regensburg. The song is originally a joke song from the 18th century that tells of a group of Swabian and Bavarian colonists who drove from Ulm via Regensburg down the Danube towards Hungary. The strudel that is sung about in the song is located below the Austrian town of Grein. There is a text version from 1840, the title of which, "When we once came from Regensburg", is closer to the original and the historically tangible background of the colonization in the east than the lyrics in use today.

Shipping in the bridge area

Especially because of the Danube vortex created by the bridge ( Regensburger Strudel ) directly below the bridge, all ships had to be towed upstream until the 20th century due to insufficient propulsion . From 1916 to 1964 there was an electrically operated ship through system . On July 21, 2012 the towing system was put back into operation.

The dimensions of the arches in the stone bridge no longer met the requirements of modern inland shipping . As part of the expansion of the European waterway Rotterdam - Constanza, the Regensburg European Canal was built to bypass the Stone Bridge .

During the construction of the canal, a barrage was built upstream at Pfaffenstein for the north and south arms of the Danube. No shipping is possible on the northern arm of the Danube. Since the construction of the barrage in the urban area of Regensburg, shipping has ended on the southern arm of the Danube at the Iron Bridge . Only pleasure boats and smaller excursion boats, but not the large cruise liners, can pass the Stone Bridge on the southern arm of the Danube, whereby the excursion boats use the passage through the Stone Bridge as an attraction. On the southern arm of the Danube, due to the barrage at Pfaffenstein, it is not possible to continue upstream, but there is a lock for pleasure craft there.

After the barrage near the A 93 motorway bridge , the Europakanal runs north of both branches of the Danube and north of the Stadtamhof district . After Stadtamhof, the Danube Canal joins the Regen River and shortly thereafter with the northern arm of the Danube. After a further estuary stretch of 420 m, the combined waters of the canal, rain and Danube northern arm meet at river kilometer 2378.82 on the southern arm of the Danube river.

Surroundings

Immediately next to the southern bridge driveway is the historic Wurstkuchl , which was built in the first half of the 17th century to the north directly on the city wall of the 14th century . After the demolition of the city wall in the middle of the 19th century, remnants of the city wall remained on the building that still exists today.

The Danube Shipping Museum Regensburg is located a little downstream of the Stone Bridge on the right (southern) bank .

Others

The bridge was the motif of a stamp issued in 2000 for 1.10 DM / 0.56 EUR of the definitive series Sights of the Deutsche Post AG . In 2007 it was nominated for the award as a historical landmark of civil engineering in Germany .

See also

literature

- Karl Bauer : Regensburg, art, culture and everyday history . MZ-Verlag Regensburg, 6th edition 2014, ISBN 978-3-86646-300-4, p. 218 ff.

- Eberhard Dünninger: Weltwunder Steinerne Brücke, texts and views from 850 years , book and art publisher Oberpfalz 1996, ISBN 3-924350-54-X

- Edith Feistner (ed.): The Stone Bridge in Regensburg (= Forum Middle Ages, Volume 1), Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2005, ISBN 3-7954-1699-X

- Helmut-Eberhard Paulus: Stone Bridge with Regensburg and Amberger Salzstadel and a trip to the historical sausage kitchen (= Regensburger Taschenbücher, Volume 2), book publisher of the Mittelbayerische Zeitung, Regensburg 1993, ISBN 3-927529-61-3

- Franz von Rziha : The stone bridge near Regensburg. In: Allgemeine Bauzeitung , year 1878, pp. 45–49 (online at ANNO ).

- Georg Küffner: Regensburg's Stone Bridge. Milled, fitted and glued on . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . November 1, 2016, ISSN 0174-4909 , p. T1 ( faz.net [accessed November 5, 2016]).

Web links

- Johann Schönsteiner: Description of the Danube Bridge Regensburg - Stone Bridge ( Memento from January 5, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- University of Regensburg: The builder's bond with the devil

- Site of the city of Regensburg for the renovation of the bridge

- Stone bridge as a 3D model in SketchUp's 3D warehouse

Individual evidence

- ^ Robert Hoff: Masterpieces of the engineering art. Bundesanzeiger-Verlag, Cologne 2001, ISBN 3-88784-886-1 .

- ↑ a b c d Ralph Egermann: Transport structure and monument. Aspects in the planning and execution of the current repair work on the Stone Bridge in Regensburg . In: City of Regensburg, Lower Monument Protection Authority (Hrsg.): Preservation of monuments in Regensburg . tape 14 . Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-7917-2708-0 , pp. 108 ff .

- ↑ a b c City of Regensburg: Stone Bridge, History ( Memento of the original from November 29, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ A b Karl Bauer: Regensburg, Art, Culture and Everyday History , MZ-Buchverlag, 6th edition 2014, ISBN 978-3-86646-300-4 , p. 218ff.

- ↑ Klaus Heilmeier: A desert island and more of a village than a suburb. Searching for traces on the Untere Wöhrd . In: City of Regensburg, Office for Archives and Preservation of Monuments (ed.): Preservation of monuments in Regensburg . tape 13 . Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2550-5 , pp. 126 .

- ↑ a b The stone bridge in Regensburg . In: Die Denkmalpflege , Volume 1, No. 6 (May 3, 1899), p. 50

- ^ Johann Schönsteiner: Description of the Danube bridge Regensburg - Stone Bridge . In: Stone bridges in Germany . Beton-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1988, ISBN 3-7640-0240-9 . Summary as short texts on the preservation of monuments in Fraunhofer IRB - Baufachinformation.de ( Memento from January 5, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ City of Regensburg: Stone Bridge, Technical Data ( Memento of the original from December 1, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Silvia Codreanu-Windauer, Michael Schmidt: The stone bridge of Regensburg. Multifunctional building and medieval wonder of the world . In: Prof. Dr. Egon Johannes Greipl (Ed.): Monument preservation information . No. 149 , ISSN 1863-7590 , p. 34 .

- ^ A b c Friedrich stand foot, Joachim Naumann: Bridges in Germany for roads and ways (II) . Deutscher Bundes-Verlag, Cologne 2007, ISBN 3-93506-446-2 , p. 12

- ^ Marion Bayer: A history of Germany in 100 buildings. Cologne 2015, p. 68.

- ↑ Lutz Michael Dallmeier and Mathias Hensch : Secrets of the Stone Bridge. New archaeological information on the medieval development of the southern bridgehead . In: City of Regensburg, Office for Archives and Preservation of Monuments (ed.): Preservation of monuments in Regensburg . tape 12 . Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-7917-2371-6 , pp. 6 .

- ↑ The Katharinenspital at the Steinernen Brücke on www.spital.de - Retrieved on December 5, 2013

- ↑ Eberhard Dünninger: Weltwunder Steinerne Brücke, texts and views from 850 years , Buch & Kunstverlag Oberpfalz 1996, ill. P. 35

- ↑ Marianne Sperb: In the balancing act between monument and traffic route , Mittelbayerische Zeitung November 16, 1996

- ^ Eugen Trapp: "Common property of all Germans" Regensburg Monuments in the National Context 1810-1918 . In: Working Group Regensburg Autumn Symposium (ed.): "To the devil with the monuments" 200 years of monument protection in Regensburg . tape 25 . Dr. Peter Morsbach Verlag, Regensburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-937527-41-3 , pp. 11-12 .

- ^ Karl Bauer: Regensburg , MZ Buchverlag 2014, ISBN 978-3-86646-300-4 , p. 223

- ^ A b Ralph Egermann: Transport structure and monument. Aspects in the planning and execution of the current repair work on the Stone Bridge in Regensburg . In: City of Regensburg, Lower Monument Protection Authority (Hrsg.): Preservation of monuments in Regensburg . tape 14 . Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-7917-2708-0 , pp. 109 .

- ^ Sigfrid Färber: Regensburg, then, yesterday and today. The image of the city over the last 125 years . JF Steinkopf Verlag, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-7984-0588-3 , p. 96, 97 .

- ↑ Peter Morsbach: Regensburg as a monument to the German spirit in the Third Reich . In: Working Group Regensburg Autumn Symposium (ed.): "To the devil with the monuments" 200 years of monument protection in Regensburg . tape 25 . Dr. Peter Morsbach Verlag, Regensburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-937527-41-3 , pp. 39 .

- ↑ Divers are looking for Bruckmandl-Arm on Mittelbayerische.de - Retrieved January 10, 2013

- ↑ Bruckmandl restored: Regensburg's landmark has an arm again. Bayerischer Rundfunk, September 1, 2016, accessed on July 4, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Bavaria's top conservationist: Stones for the renovation of the Stone Bridge are not enough on www.wochenblatt.de

- ↑ Problems with the renovation of the stone bridge ( memento of February 18, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) at www.br.de

- ^ Ralph Egermann: Traffic structure and monument. Aspects in the planning and execution of the current repair work on the Stone Bridge in Regensburg . In: City of Regensburg, Lower Monument Protection Authority (Hrsg.): Preservation of monuments in Regensburg . tape 14 . Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-7917-2708-0 , pp. 118 ff .

- ^ "Steinerne": City announces the construction company on www.mittelbayerische.de

- ↑ On the bridge you can finally go to www.mittelbayerische.de

- ↑ 2010-2018 - Repair of the stone bridge on regensburg.de. Retrieved June 16, 2019

- ↑ regensburg.de: Building bridges: June 10, 2018 is World Heritage Day again

- ↑ Juliane Korelski: Regensburger Sagen und Legenden (audio book), John Media 2009, ISBN 978-3-9811250-9-2 . Say about the bridge man.

- ↑ When we were recently in Regensburg , historical-critical song dictionary

- ↑ Treidelanlage Stone Bridge

Remarks

- ↑ Only the pillars of the Roman bridge in Trier have survived; their stone arches were of more recent date; after being blown up by the French army in 1689, they were rebuilt in 1716–1718. The Drusus Bridge near Bingen am Rhein was built in the 11th century, also destroyed in 1689 and rebuilt in 1772. In 1945 it was blown up by German troops; In 1952 it was rebuilt - widened. The Old Main Bridge in Würzburg was built around 1120, but was replaced by a new one from 1476. The medieval Dresden Elbe Bridge , the predecessor of the Augustus Bridge in Dresden , was built from 1119 to 1222, but was so damaged in the Magdalene flood of 1342 that it had to be replaced by a new building.

- ↑ The dam - called Beschlächt - is walkable and accessible from both sides.

- ↑ The canal runs another 500 m further between the north and south arms of the Danube to the east, then joins the north arm, flows into the rain and at the end joins again with the south arm of the Danube.