The Great Carbuncle

The Great Carbuncle , German The big carbuncle , is a 1836 published story by American author Nathaniel Hawthorne .

It is about treasure hunters who hope to find the "great carbuncle " in the " White Mountains " of New Hampshire , a legendary, shining gemstone. A young married couple discovers it, but does not dare to approach its glistening light, turns around and thus decides in favor of domestic happiness in honorable modesty. The Great Carbuncle was very popular in the 19th century, but suffered less well in later literary criticism. The one-dimensionality of the noticeably allegorically drawn figures and the moralism of the narrative are often criticized . Source research has shown, however, that it has a complex intertextual relationship to a large number of biblical, literary and historiographical texts.

content

The story begins with a description of a campfire in the wilderness of the White Mountains, where eight treasure hunters met for an evening, driven by the “selfish and solitary desire” to find the “Great Carbuncle”, a legendary gem of immeasurable value Value. It is said that on some nights its glow can be seen far away, even from the sea, but no one has ever been able to find it. According to “Indian tradition,” a ghost guarded the carbuncle “and confused those who sought it, either by moving it from peak to peak of the highest mountains or by causing a mist to rise from the enchanted lake over which the stone hung . "

Only one of the eight, called "the cynic", has a different goal: He wants to try to "set foot on every peak of these mountains" in order to prove to the world that "the great carbuncle is nothing more than humbug." He mockingly asks the others what they intend to do with the jewel. For the oldest of them, called “the seeker,” the search itself has become part of life: “The striving for it alone is my strength, the energy of my soul.” When he finds the carbuncle, he will take it to a cave and lie down there “down to die, and there he will be buried with me forever.” The next to answer is the chemist Dr. Cacaphodel. He wants the carbuncle "broken down into its original elements," so piecemeal ground, dissolve in acids, melt and burn, and finally "in the results of his research Foliantenband bequeath the world." The third is Master Ichabod Pigsnort a "weighty Kaufmann and Selectman from Boston , also church elder; “he wants to sell the carbuncle to the highest bidder. The fourth is a nameless poet; he would like to look at the carbuncle “day and night [...] it will penetrate all my mental faculties and shine brightly from every line of the poetry that I write down. So the splendor of the great carbuncle will flare around my name for centuries after my death. ”The fifth is Lord De Vere , offspring of a venerable noble house; he wants to place the jewel in the great hall of the castle of his ancestors, where he should "sparkle on the armor, banners and coats of arms" and "keep the memory of heroes shining". The last two are Matthew and Hannah, a newlywed couple of simple minds; they want to light up their hut with the carbuncle in winter, and "it will be so nice to show it to the neighbors when they come to visit us."

The next morning the treasure hunters go their way. The story follows Hannah and Matthew, who end up in increasingly barren landscapes on their way up the mountain. After almost getting lost in a thick fog, they actually find the enchanted lake, illuminated by glistening light. On the cliff under the carbuncle they see the figure of the seeker, arms outstretched, face upturned, he "did not move, however, as if he had frozen in marble." Suddenly the cynic joins them, who is still not want to believe in the carbuncle. At Matthew's request, he takes off his sooty glasses, looks at the carbuncle, and is incurably blinded by its light. Fear now overwhelms Matthew and Hannah, they return home and vow never again to "wish for more light than all the world can share with us."

At the end, the further fate of the eight treasure hunters is described: Hannah and Matthew spent “many peaceful years together and loved telling the legend of the great carbuncle.” Over the years, however, she was given less and less faith, but the narrator himself thinks he had seen from a distance a “wonderful light” in the mountains, and “the belief in poetry enticed me to become the youngest pilgrim of the great carbuncle.”

Work context

Origin and publication history

The Great Carbuncle first appeared in The Token and Atlantic Souvenir for 1837. The title page of this volume shows the year 1837, but it is certain that it was available in bookshops before Christmas 1836; the token , a literary almanac for high demands, was specifically designed as a Christmas or New Year gift. Between 1831 and 1838 the token was the most eager buyer of Hawthorne's short stories, and in the year 1837 alone there were seven other contributions from his pen. However, this fact remained unknown to the public for a long time, as Hawthorne always published his stories anonymously at the time. The Great Carbuncle is at least provided with the note in the token that the story is by the same author as The Wedding Knell , which appeared in the previous edition. In the spring of 1837, Hawthorne published The Great Carbuncle again in his first collection of short stories, Twice-Told Tales , which was also drawn by name, and so publicly identified himself as the author of this and other stories.

Originally, however, the story was almost certainly part of a larger work, The Story Teller , which Hawthorne wrote between 1832 and 1834, but which as a whole never appeared and has not survived. Hawthorne had found a publisher for Story Teller, unlike his first two, now also lost, narrative cycles Seven Tales of My Native Land (around 1826-27) and Provincial Tales (around 1828-1830), but after the first parts in November and December 1834 were in New England Magazine , the magazine changed hands and suspended publication. Ultimately, Hawthorne only published a few individual stories from the Story Teller , some in New England Magazine , some in other publications such as the Token . The context of the work was lost, but can be conclusively reconstructed in the case of The Great Carbuncle .

The story teller is therefore a series of short stories that are embedded in a general narrative. First-person narrator and at the same time the protagonist of the framework plot is a storyteller named " Oberon " (named after the character in Shakespeare's Midsummer Night 's Dream ) wandering through New England . The action places many individual stories of the storytellers can be doing some fragments of the frame assigned to Hawthorne later declared as " sketches " (sketches) , but as yet unpublished. The Great Carbuncle is closely related to the frame fragments The Notch and Our Evening Party among the Mountains , which Hawthorne published along with other travel sketches in November 1835 under the collective title Sketches from Memory in New England Magazine . Oberon describes his hike through the White Mountains , the "White Mountains" of the state of New Hampshire , where the plot of The Great Carbuncle is set. The story The Ambitious Guest , published in June 1835, also plays here , which thematically has many overlaps with The Great Carbuncle . According to Alfred Weber's reconstruction of the Story Teller, the first two paragraphs of The Notch introduced Oberon's hike through the White Mountains, followed by The Ambitious Guest and the second part of The Notch . This was followed by Our Evening Party among the Mountains and finally The Great Carbuncle , the subsequent frame parts have not been preserved.

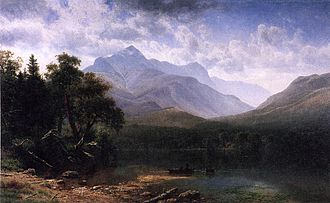

Hawthorne himself toured the White Mountains in September 1832; presumably he wrote The Great Carbuncle and The Ambitious Guest soon after. He published a second time in 1850 with The Great Stone Face a story about the White Mountains, but it was probably not written a few years later and is therefore not directly related to the Story Teller . A reference to The Great Carbuncle can also be found in the story A Virtuoso's Collection, first published in 1842 and again in 1846 in Mosses from an Old Manse . Here the first-person narrator is guided through a museum in which a wide variety of curiosities from literary history are exhibited. In addition to the white fleece from Spenser's Faerie Queene and the skeleton of Don Quixote's loyal warhorse Rosinante, he also sees his own literary creation, the large carbuncle (one of the wild projects of my youth) , exhibited in a disdainful display case and not nearly as brilliant as he remembered it - in the words of Helmut Schwarztrauber, A Virtuoso's Collection illustrates the perversion of the imagination, "the materialization of everything spiritual through a rationalistically founded realism."

Position in the context of the story teller

In his work, Alfred Weber makes it clear that the internal narratives of the Story Teller are in many ways related to the framework plot and also to each other: Oberon not only places the stories in a geographically and atmospherically appropriate narrative situation, but sometimes also comments on their relevance and meaning. Conversely, many details of the framework plot can be found in the internal narratives, even if they are often strangely distorted. In the second part of The Notch sketch, Oberon passes the Crawford Notch canyon . On the way to Ethan Crawford's inn, he is passed by a group of tourists, including a mineralogist with green glasses, a gallantly dressed young man reciting a poem by Lord Byron , and a Portland merchant. In the subsequent sketch, Our Evening Party among the Mountains , he reaches the inn and meets other travelers, including two young couples on their honeymoon. In these coincidental companions of Oberon, it is easy to see role models for the adventurers in The Great Carbuncle , exaggerated into caricatures , for the chemist Cacaphodel (who also wears glasses), the uninspired poet, the merchant Ichabod Pigsnort and for Matthew and Hannah, the young one Married couple.

Later, like the other tourists, Oberon appears in the drawing room, where people chat in good company - the situation is reflected in The Great Carbuncle in the evening gathering of treasure hunters around the campfire. Oberon holds back the conversation, but listens carefully. He is particularly impressed by an Indian legend that one of the tourists tells of. It is about a large carbuncle who is said to be enthroned high in the mountains over a lake and is guarded by a ghost. Oberon came up with the idea of making “a story with a deep moral” out of this material ('On this theme methinks I could frame a tale with a deep moral') . Finally the round dissolves, because early in the morning you want to hike together to Mount Washington six miles away , probably to look for the “big carbuncle” there, as Oberon humorously notes. How The Great Carbuncle joined Our Evening Party among the Mountains is unclear, also because it is uncertain how much this fragment was edited or shortened when it was published. Due to some content-related bracing, it seems certain that Oberon is identical to the first-person narrator from The Great Carbuncle . Weber speculates that the story is a dream of Oberon - in bed, the legend may have run through his head for a long time. The strange parallels between the frame narrative and the inner narrative were therefore explained as “ remnants of the day ” that return distorted in the dream. In this way, the genre of this peculiar narrative can finally be determined more precisely: it should be viewed as a “fairytale trauma allegory”.

Several commentators have pointed out the parallels to The Ambitious Guest , which probably preceded the story in Story Teller . Both stories are set in the White Mountains, and both assert that they describe events that actually happened in a more or less remote past and have now become legend . Both stories begin with the description of a group of people who in the evening talk about their plans and wishes in front of a warming fire. While the "ambitious guest" is punished by fate for his arrogant pursuit of fame and disappears from the earth without a trace, Matthew and Hannah are given the insight that their selfish search will bring them no luck. These two opposing resolutions are symbolic of Oberon's ambivalent feelings in search of his own destiny in life. These doubts are the fundamental theme of the story teller's framework , which is equivalent to an educational novel. The Great Carbuncle also seems to echo in Oberon's last diary entries, published in 1837 as Fragments from the Journal of a Solitary Man : Shortly before his death, he is obsessed with the thought “that I have never discovered the true secret of my powers; that there was a treasure within reach, a gold mine under my feet, worthless because I never knew how to look for it. "

Interpretations

Reception history

The Great Carbuncle was received extremely positively by contemporary critics . Henry Wadsworth Longfellow stated in the North American Review in 1837 in his review of the Twice-Told Tales that he liked this story best and expressed his regret that it could not be reprinted in full. Even Elizabeth Palmer Peabody appeared the following year in The New Yorker very impressed: The Story connect on most excellent the "wild imagination" and "allegorical spirit" of Germany with the common sense of the Englishman and the natural sensitivity of the American. Henry James also praised the story in his Hawthorne biography in 1879, but noted that the story, like some of Hawthorne's other works, after forty years no longer seems quite as fresh and original as it must have seemed to the American reader at the time as a contrast to the otherwise rather dry magazine prose of this time.

Although it has been anthologized more often since then , the appreciation of literary critics for the story declined noticeably over time. Lea Bertani Vozar Newman attributes this as well as her former popularity to the fact that she is one of the most conventional works of Hawthornes. Both WR Thompson and Patrick Morrow, two of the few literary scholars who have attempted an in-depth analysis so far, conclude that The Great Carbuncle fails as a story. Thompson complains that the characters remain static and that too much space is given to their description, so that the plot never really gets going. Morrow states that the story completely lacks the psychological and moral complexity and sensitivity that characterized Hawthorne's masterpieces; From the description of the landscape to the fate of the protagonists, everything is too explicitly pre-spelled for the reader to develop compassionate interest. Doubleday objects that figures in an allegory like The Great Carbuncle represent "types", that is, they are necessarily static. But even he is not very fond of the story that the problem is not that it is an allegory, but that it is a failed allegory.

Morrow, Thompson and Neal Frank Doubleday, however, go to the trouble of detailing the personnel of Hawthorne's allegory and getting to the heart of the "moral" of the story. Thompson also refers to possible biblical models. Michael J. Colacurcio and David S. Ramsey, on the other hand, focus on the specific American context of the narrative and Hawthorne's handling of historical sources.

Allegory and Satire

The Great Carbuncle brings together features of different genres and literary traditions. Terence Martin recognizes characteristics of the fairy tale in the story , especially in the opening sentence, which locates the plot "in old times" ('At nightfall, once in the olden time ...') and may represent a variation of the formula " Once upon a time ... ". The stencil-like exaggeration of the eight characters makes them appear to many interpreters as mere personifications of their determining traits (such as greed, arrogance, disbelief), especially since some (“the cynic”, “the poet”, “the seeker”) are only named with him ; the narrative as a whole thus clearly shows features of allegory . Specifically, reference has been made to the influence of the most famous allegory in English literary history, John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress (1678), the first book Hawthorne learned to read at the age of four. The designation of the treasure hunters - and finally the narrator himself - as the " pilgrims " of the great carbuncle points to Bunyan . The various landscapes that Hannah and Matthew wander through on their ascent resemble the allegorical stations of Bunyan's pilgrims (such as the "Valley of Humiliation," the "Lovely Mountains," the "Enchanted Ground" and finally the "Heavenly City"). Bunyan, who came from the Puritan tradition, shares with Hawthorne's New England ancestors and his contemporaries a penchant for religious typology , and so the allegorical elements can also be read as an appropriation or a parody of the sermons of Puritanism or the revival movements, New England and New York recorded with some regularity during Hawthorne's lifetime.

In addition to the fairytale and allegorical, ie “timeless” features, the story also contains references to its specific historical and cultural context. Geographically, for example, it is located in the mountains of New Hampshire, and a reference to the explorations of John Smith suggests that the story, like many of Hawthorne's works, is set in the colonial days of New England. The description of the figures also contains very specific information and thus reveals hints of political or social satire . This is particularly clear in the case of Ichabod Pigsnort: He is the parish council of the First Church in Boston, the most prestigious congregation in New England. His fear of God is at least as pronounced as his greed - it is said that he (similar to Dagobert Duck ) had the "habit of rolling naked in a huge pile of shillings for an hour after prayer every morning and evening." Hawthorne's caricature of the New England elites also offers a direct literary role model, namely Ichabod Crane, the Yankee schoolmaster who is teased in Washington Irving's genre- defining short story The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1820). Hawthorne's Ichabod also overtakes poetic justice ; He is finally kidnapped by Indians to Canada, has to pay a high ransom and, for the rest of his life, “rarely owned copper worth six pence.” The description of the chemist Dr. Cacaphodel, a small elderly person, almost a mummy, who wore a "crucible-shaped hat." William Collins Watterson recognizes in him a caricature of Parker Cleaveland , the "father of American mineralogy," whose eccentric appearance was Hawthorne during his student days at Bowdoin College . But there is also a literary role model for Cacaphodel, the pharmacist “Cacafogo” in Oliver Goldsmith's The Citizen of the World (1760–1762).

Morrow and Doubleday blame the mixture of allegorical and satirical elements for the “failure” of the story, the French Renaud Zuppinger, on the other hand, sees it as a successful innovation: Hawthorne's allegory, on the one hand, ties in with a classical (or classical) tradition and also knows it To preserve the unity of time, place and action , on the other hand he creates a more or less realistic social panorama through the " carnivalesque " collection of such different figures, a comédie humaine corresponding to its time . For other critics, however, the narrative's parable character ultimately predominates . Both Thompson and Morrow see Christian brotherhood , or rather its lack, as the central theme of the narrative. Terence Martin sees Matthew's and Hannah's decision as an affirmation of the ideal of modest domesticity, which characterizes contemporary women's magazines in particular, but also many of Hawthorne's works (such as The Ambitious Guest ). Alfred Weber also sees the “moral” of the story in the knowledge that human happiness is only possible “in the familiar area of everyday life and in the glow of the domestic hearth”. To many of the commentators in this story, the didactic-moralistic gesture seems downright intrusive; Alison Easton suspects, however, that Hawthorne is doing parody here or at least drawing a pastiche of the staid, often maudlin, devotional literature of his time.

Morrow also explains that the story is at the same time a parable about the limits and dangers of knowledge : in the case of the seeker as well as that of the cynic, the search for carbuncle takes on monomaniacal , ultimately self-destructive features; the one pays for it with his life, the other loses his sight - Morrow compares her fate with the captain Ahabs in Melville's Moby-Dick . Hannah and Matthew, on the other hand, were the least ethically guilty of the narrative, but they bought their peace of mind with a lack of knowledge. Colacurcio also notes that their “redemption” is by no means certain, as the previous story shows - just like the doomed family in The Ambitious Guest , their modest hut could be destroyed at any time by an indifferent or angry god.

Biblical references

WR Thompson cites some biblical subtexts for the narrative that are already suggested by Hawthorne's naming, for three of his characters have biblical names, and his narrator remarks on Hannah and Matthew that they are “two simple names that go well with the simple one Couple fit ”. The name Ichabod is explained in the 1st book of Samuel : It means “inglorious” in Hebrew ( 1 Sam 4,21 EU : “She called the boy Ikabod - that means: The glory is gone from Israel”) and consequently also fits with it derisive description of the Pharisee Ichabod Pigsnort (Pigsnort literally means "pigsnort").

The story of Hanna can also be found in Book 1 of Samuel . Every year she made a pilgrimage to Shiloh , the highest shrine of the Israelites, to ask the Lord to be delivered from her sterility. Thompson sees the course and the moral of Hawthorne's story in the so-called "hymn of praise of Hanna" ( 1 Sam 2,1-10 LUT ) in detail. In her prayer she praises the righteousness of the Lord, who always assists the weak ("Actions are weighed by him. The bow of the strong is broken, and the weak are girded with strength ... The LORD makes poor and makes rich; He humbles and exalts "). The fate of Ichabod Pigsnort seems to be mapped out in Hanna's hymn of praise (“Those who were full must serve for bread”) as the blinding of the cynic (“the wicked are to be destroyed in darkness”). Their confidence that the Lord would “protect the feet of his saints” is also reminiscent of the ascent of Hawthorne: Hannah and Matthew, according to the narrator, probably tried to “climb as high and as high as they were for between heaven and earth her feet found support, “and when Hannah stumbles and threatens to slip, she catches herself in time.

Finally, the name Matthew points to the Gospel of Matthew ; Here, in particular, a famous passage from the Sermon on the Mount of Jesus can be plausibly linked to The Great Carbuncle : “You are the light of the world. A city on top of a mountain cannot be hidden. You don't light a light and put a vessel over it, you put it on the candlestick; then it lights up everyone in the house. Let your light shine before people so that they can see your good works and praise your Father in heaven ”( Mt 5 : 14-16 EU ). The poet, on the other hand, plans to take the carbuncle to his room in London, hidden under his coat, so that he can have it all to himself; the cynic replies mockingly: “Hide it under your coat, you say? It will shine through the holes and you will look like a jack-o'-lantern! ”Hannah and Matthew want the carbuncle for themselves too, so that it can illuminate their home on the long winter evenings, but ultimately decide in line with the biblical promise on the other hand: “In the evening we light a cheerful fire in our fireplace and we will be happy in its glow. But never again do we want to wish for more light than all the world can share with us. ”Michael J. Colacurcio notes that, remembering Morrow's interpretation, another neighboring Matthew passage imposes itself as a reference, namely Mt 5.3:“ Blessed are who are spiritually poor; for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. "

History and wilderness

The fact that Hawthorne set The Great Carbuncle and many of his other stories in his native New England is to be seen in connection with the contemporary effort to establish an independent American national literature. The pristine, “virgin” nature of America has become an important topos of American literature, but for generations many American writers have complained that America seemed to lack a rich past from which literary capital could be made; Many of Edgar Allan Poe's gruesome stories still take place in the centuries-old castles, palaces and monasteries of feudal Europe. Hawthorne, on the other hand, followed in many ways the example of Washington Irving , who set his stories Rip Van Winkle and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1819–1820), both based on German folk tales, in the colonial days of his home state New York and passed them off as American " legends " . Hawthorne also emphasizes in The Great Carbuncle as well as in The Ambitious Guest that he falls back on "popular" material and describes events that actually occurred in a more or less distant past and have since been passed down orally or at least in dusty old chronicles can be read. The important thing is that it is tied to a specific location, just as Irving's stories transfigured the Catskills into a legendary pastoral idyll , so Hawthorne helped the “wild” White Mountains to acquire a historical patina . Irving's Sketch Book may have served as a model for Hawthorne in other ways; As in the Story Teller , the stories in the Sketch Book are embedded in a frame narrative that is equivalent to an artist biography of the first-person narrator (Oberon in Hawthorne, “Dietrich Knickerbocker” in Irving).

According to Leo B. Levy, the image of nature in The Great Carbuncle is untypical for Hawthorne. In contrast to his contemporaries James Fenimore Cooper and Henry David Thoreau , he hardly depicts nature in its originality in his works, but mostly already composed, interpreted and designed in the sense of the Picturesque aesthetic. Hawthorne, however, distrusts the aesthetics of the sublime , the feeling of being overwhelmed and awe in the face of an "untamed" nature, as well as any emotion that requires unconditional devotion and is not balanced by the mind. Hannah and Matthew also fear what is unfamiliar and inexplicable to them on their ascent to the summit:

|

|

Nevertheless, according to Levy, The Great Carbuncle is next to The Great Stone Face one of the few stories by Hawthorne in which he places the sublime over the “picturesque”, because in the end Hannah and Matthew find the carbuncle, the epitome of the sublime, “then left shuddering and in reverent admiration the eyelids droop to exclude the dazzling splendor ”; Hawthorne makes it clear that this was granted to them precisely by their simple mind and their naive faith (whereas the "cynic" is blinded at the sight). The fact that they do not take the carbuncle and instead remember their domestic happiness does not contradict this interpretation: it rather illustrates the insight that the sublime cannot be “grasped” from a human perspective. Ultimately, according to Levy, it is not the romantic experience of nature that is central to the story, but ultimately a religious experience: The Great Carbuncle is therefore a parable about the spiritual condition of the Puritans of New England and their unconditional devotion to an almighty and inexplicable God.

David S. Ramsey criticizes the national romantic premises. It is true that the story is popular in the sense that Hawthorne, as he believes, mainly referred to the oral tradition of the Crawford family, whose inn in the White Mountains was visited by Hawthorne on his journey in 1832, as did his alter ego Oberon in the story Plate . This folklore is preserved in Lucy Crawford's History of the White Mountains (1846). According to this, the legend of the "Great Carbuncle" is originally an Indian legend: According to this, the Indians who previously settled the area once killed one of their own so that his spirit would watch that this treasure did not fall into the hands of the whites. Ramsey believes that the fact that Indians play no role in Hawthorne's story is significant. In the narrative itself they are only mentioned in a short aside, and Oberon frankly admits in the opening sketch that he actually abhor Indian stories ('I do abhor an Indian story') . In the supposedly pluralistic microcosm that Hawthorne imagines with the campfire of the treasure hunters, there is no place for the natives, the story ultimately turns out to be a "cultural monologue."

Source research and historicist interpretations

Source research considers various models for The Great Carbuncle . Like Ramsey, Neal Frank Doubleday believes that Hawthorne may have heard of the carbuncle in Crawford's Ethan's Inn, but he cites an episode in the 19th chapter of Walter Scott's novel The Pirate (1822) as a literary model . Not only is there an eerily glowing carbuncle that becomes invisible and thus inaccessible to anyone who is looking for it, Doubleday also sees the "morals" of The Great Carbuncle as modeled here: Scott's fictional character Norna complains that she is impetuous in her Young people coveted the unattainable and used "forbidden means" to increase their knowledge. This Faustian desire to overcome the limits of knowledge (or mortality) at all costs is central to many other stories by Hawthorne; Doubleday specifically cites Ethan Brand and The Birthmark for comparison.

Kenneth Walter Cameron points to a passage in Jeremy Belknaps The History of New-Hampshire (1784–1792) as a possible source. Belknap reports that the Indians believed that "invisible beings" lived on the summit of Agiocochook ( Mount Washington ) and warned against climbing the summit. English prisoners of war, who were dragged through this area to Canada by the Indians, would have seen carbuncle glow in the peaks at night.

Hawthorne's narrator himself names two authorities for the legend of the "great carbuncle," one indirectly, one explicitly. As Michael J. Colacurcio shows, the story appears in a completely different light if one follows Hawthorne's advice and also visits these sources; the ironies that arise are absolutely incomprehensible. On the one hand, Oberon makes vague references in Our Evening Party among the Mountains to the " biographer of the Indian chiefs " ('the biographer of the Indian chiefs') . What is obviously meant is Samuel Gardner Drake's Indian Biography (1832); In the only mention of the White Mountains in this work, however, there is no mention of a precious stone, only of an enigmatic lake high in the mountains, from which, in the sunshine, a large pillar of vapor rose up from which a cloud eventually formed. On the other hand, Hawthorne claims in a footnote at the beginning of the story that “Sullivan, in his story Maines, written after the revolution” reports that the existence of the carbuncle was not yet completely ruled out in his time. But if one looks at the corresponding passage in James Sullivan's History of the District of Maine (1795), one can only read there, “The savages of North America, cunning as they were”, would soon have recognized the greed of the white settlers and maliciously encouraged them "In their fruitless search for mountains full of ore" and an "immensely large and valuable gemstone" that can be found on a certain peak.

Colacurcio further refers to the source research John Seelyes, according to which Hawthorne in The Great Carbuncle falls back on the notes of John Winthrop . Winthrop, one of the founders of the Massachusetts Colony, circulated Indian accounts of a "great lake" from which most and most valuable beaver pelts came and ponders how he can gain control of these resources. The fact that Hawthorne had an association with Winthrop is shown by the passage from the Sermon on the Mount, interpreted by Thompson as a subtext of the narrative - it is at the center of the famous sermon (A Model of Christian Charity) , which Winthrop 1630 shortly before the puritanicals went ashore Settlers held on to mark the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony . Winthrops Trope from City upon a Hill , the "city on the hill ," urged the settlers to be an example to the world, and is still considered one of the first and most powerful manifestations of American "exceptionalism" . Colacurcio senses Hawthorne's subversive intent behind all these ironies. The carbuncle therefore represents nothing less than the “idea of America,” and its “strategic absence” in history is decisive - no one ever sees it as more than a reflection, but never the jewel itself.

literature

expenditure

The first edition of the story can be found in:

- SG Goodrich (Ed.): The Token and Atlantic Souvenir: A Christmas and New Year's Present . Charles Bowen, Boston 1837, pp. 156-75.

The main edition of the work, the Centenary Edition of the Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Ohio State University Press, Columbus OH 1962 ff.), Contains The Great Carbuncle in Volume IX ( Twice-Told Tales , edited by Fredson Bowers and J. Donald Crowley) 1974), pp. 149-65. Some of the numerous anthologies of Hawthorne's short stories contain the narrative; A popular reading edition based on the Centenary Edition is:

- Nathaniel Hawthorne: Tales and Sketches . Edited by Roy Harvey Pearce . Library of America , New York 1982. ISBN 1-883011-33-7

An e-text can be found on the pages of Wikisource :

There are several translations into German:

-

The great carbuncle . German by Franz Blei . In: Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Wedding of the Dead . Südbayerische Verlagsanstalt, Munich-Pullach 1922 ( digitized from the Gutenberg-DE project )

- without specifying the translator Franz Blei, this version can also be found in: Nathaniel Hawthorne: The garden of evil and other stories . Edited by RW Pinson. Magnus Verlag, Essen 1985. ISBN 3-88400-216-3

- also in: Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Forces of Evil: Eerie Tales . Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-423-14300-4 .

- The great carbuncle . German by Günter Steinig. In: Nathaniel Hawthorne: The great carbuncle. Fantastic stories . Safari-Verlag, Berlin 1959.

- The great carbuncle . German by Lore Krüger . In: Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Black Veil. Selected stories . Insel, Leipzig 1980. (= Insel-Bücherei 653)

Secondary literature

- Michael J. Colacurcio : The Province of Piety: Moral History in Hawthorne's Early Tales. Duke University Press, Durham NC 1984. ISBN 0-8223-1572-6

- Neal Frank Doubleday: Hawthorne's Early Tales: A Critical Study . Duke University Press, Durham NC 1972.

- Leo B. Levy: Hawthorne and the Sublime . In: American Literature 37: 4, 1966, pp. 391-402.

- Patrick Morrow: A Writer's Workshop: Hawthorne's 'The Great Carbuncle' . In: Studies in Short Fiction 6, 1969. pp. 157-64.

- Lea Bertani Vozar Newman : A Reader's Guide to the Short Fiction of Nathaniel Hawthorne . GK Hall, Boston 1979.

- David S. Ramsey: Sources for Hawthorne's Treatment of a White Mountain Legend . In: Studies in Language and Culture (Graduate School of Languages and Cultures, Nagoya University) 26: 1, 2004. pp. 189-201.

- WR Thompson: Theme and Method in Hawthorne's 'The Great Carbuncle' . In: South Central Bulletin 21, 1961. pp. 3-10.

- Alfred Weber : The development of the framework narratives Nathaniel Hawthorne. "The Story Teller" and other early works . Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin 1973. ISBN 3-503-00714-8

- William Collins Watterson: Professor Dearest? ( Memento from February 17, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ). In: Bowdoin Magazine , November 11, 2009.

- Renaud Zuppinger: Vanitas vanitatis; ou, La gemme mal aimée: The Great Carbuncle de Hawthorne . In: Études anglaises 46: 1, 1993. pp. 10-18.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ All previous quotes based on the translation by Lore Krüger.

- ^ Reviews appeared as early as October 1836 in The Knickerbocker and in the American Monthly Magazine ; see. entry no.7580 (The Token and Atlantic Souvenir A Christmas and New Year's Present) in the Bibliography of American Literature (restricted access, accessed January 12, 2013).

- ↑ On the history of the publication and the reconstruction of the Story Teller, see Alfred Weber: The development of the framework narratives Nathaniel Hawthornes , pp. 145 ff.

- ^ Alfred Weber: The development of the framework narratives Nathaniel Hawthornes , p. 183 ff.

- ↑ The Sketches from Memory took Hawthorne also 1854 in the extended edition of his collection Mosses from an Old Manse on; The Notch was renamed The Notch of the White Mountains . In the Centenary Edition of the Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne they can be found in Volume X (Mosses from and Old Manse) , Ohio State University Press, Columbus 1974.

- ^ Alfred Weber: Hawthorne's Tour of 1832 through New England and Upstate New York . In: Alfred Weber, Beth Lueck and Dennis Berthold (eds.): Hawthorne's American Travel Sketches . University Press of New England, Hanover NH 1989. pp. 183-185.

- ↑ Helmut Schwarztraub: Fiction of Fiction. Justification and preservation of narration through theoretical self-reflection in the work of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allen Poe . University Publishing House C. Winter, Heidelberg 2000. (= English Research 281; Simultaneously Habil.-Schrift, Erfurt University of Education , 1996/97); Pp. 151-152.

- ^ Alfred Weber: The development of the framework narratives Nathaniel Hawthornes , p. 198, p. 201.

- ^ Alfred Weber: The development of the framework narratives Nathaniel Hawthornes , pp. 198-199.

- ^ Alfred Weber: The development of the framework narratives Nathaniel Hawthornes , pp. 206-208.

- ↑ Alfred Weber: The development of the framework narratives Nathaniel Hawthornes , p. 205.

- ↑ I am possessed, also, with the thought that I have never yet discovered the real secret of my powers; that there has been a mighty treasure within my reach, a mine of gold beneath my feet, worthless because I have never known how to seek for it . See Alfred Weber: The Development of the Frame Narratives Nathaniel Hawthornes , p. 208.

- ^ Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: Hawthorne's Twice-Told Tales . In: The North American Review 45, July 1837. pp. 59-73.

- ↑ Elizabeth Palmer Peabody: Twice-Told Tales . In: New-Yorker 5, No. 1/105, March 24, 1838.

- ↑ Henry James: Hawthorne . Macmillan and Co., London 1879. pp. 56, p. 64.

- ↑ Lea Bersani Vozar Newman: A Reader's Guide to the Short Fiction of Nathaniel Hawthorne , p. 149.

- ^ WR Thompson: Theme and Method in Hawthorne's 'The Great Carbuncle' , p. 6.

- ↑ Patrick Morrow: A Writer's Workshop: Hawthorne's 'The Great Carbuncle' , p. 157.

- ^ Neal Frank Doubleday: Hawthorne's Early Tales , p. 150.

- ^ Terence Martin: The Method of Hawthorne's Tales . In: Roy Harvey Pearce (Ed.): Hawthorne Centenary Essays . Ohio State University Press, Columbus OH 1964. pp. 9-10.

- ^ Alfred Weber: The development of the framework narratives Nathaniel Hawthorne. P. 202.

- ^ W. Stacy Johnson: Hawthorne and 'The Pilgrim's Progress' . In: The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 50: 2, 1951. pp. 156-166; esp. pp. 160-162.

- ↑ Michael J. Colacurcio: The Province of Piety. P. 510.

- ^ William Collins Watterson: Professor Dearest?

- ↑ Renaud Zuppinger: Vanitas Vanitatis. Pp. 10-11.

- ^ WR Thompson: Theme and Method in Hawthorne's 'The Great Carbuncle'. P. 7; Patrick Morrow: A Writer's Workshop: Hawthorne's 'The Great Carbuncle'. P. 159.

- ^ Alfred Weber: The development of the framework narratives Nathaniel Hawthorne. P. 204.

- ^ Alison Easton: The Making of the Hawthorne Subject. University of Missouri Press, Columbia MO 1996, p. 95.

- ↑ Patrick Morrow: A Writer's Workshop: Hawthorne's 'The Great Carbuncle'. Pp. 161-162.

- ↑ Michael J. Colacurcio: The Province of Piety. Pp. 511-512.

- ^ WR Thompson: Theme and Method in Hawthorne's 'The Great Carbuncle' , pp. 4 and 7-8.

- ^ WR Thompson: Theme and Method in Hawthorne's 'The Great Carbuncle' , pp. 8-9.

- ^ WR Thompson: Theme and Method in Hawthorne's 'The Great Carbuncle' , p. 6.

- ↑ Michael J. Colacurcio: The Province of Piety , pp. 658-659 (footnote 73).

- ^ Nelson F. Adkins : The Early Projected Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne . In: Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 39, 1945. p. 145.

- ↑ Michael J. Colacurcio: The Province of Piety , p. 513.

- ^ Leo B. Levy: Hawthorne and the Sublime , pp. 391-392.

- ^ Leo B. Levy: Hawthorne and the Sublime , p. 393.

- ^ Leo B. Levy: Hawthorne and the Sublime , p. 394.

- ↑ David S. Ramsey: Sources for Hawthorne's Treatment of a White Mountain Legend , pp. 194-195.

- ^ David S. Ramsey: Sources for Hawthorne's Treatment of a White Mountain Legend , p. 198.

- ^ Neal Frank Doubleday: Hawthorne's Early Tales , p. 146.

- ↑ 'In my childish courage, I was even but too presumptuous, and the thirst after things unattainable led me, like our primitive mother, to desire increase of knowledge, even by prohibited means [...] Often when watching by the Dwarfie Stone, with mine eyes fixed on the Ward-hill, which rises above that gloomy valley, I have distinguished, among the dark rocks, that wonderful carbuncle, which gleams ruddy as a furnace to them who view it from beneath, but has ever become invisible to him whose daring foot has scaled the precipices from which it darts its splendor. My vain and youthful bosom burned to investigate these and an hundred other mysteries ... ' Quoted in: Neal Frank Doubleday: Hawthorne's Early Tales , p. 146.

- ^ Neal Frank Doubleday: Hawthorne's Early Tales , p. 149.

- ↑ 'They had a superstitious veneration for the summit, as the habitation of invisible beings; they never ventured to ascend it, and always endeavored to dissuade every one from the attempt. From them, and the captives, whom they sometimes led to Canada, through the passes of these mountains, many fictions have been propagated, which have given rife to marvelous and incredible stories; particularly, it has been reported, that at immense and inaccessible heights, there have been seen carbuncles, which are supposed to appear luminous in the night. ' Quoted in: Kenneth Walter Cameron: Genesis of Hawthorne's The Ambitious Guest . Transcendental Books, Hartford CN 1955. p. 29.

- ↑ Michael J. Colacurcio: The Province of Piety , p. 658 (footnote 72).

- ^ John Seelye: Prophetic Waters: The River in Early American Life and Literature . Oxford University Press, New York 1977. pp. 161 ff.

- ↑ Michael J. Colacurcio: The Province of Piety , p. 659 (footnote 73).

- ↑ Michael J. Colacurcio: The Province of Piety , p. 512.