Urraca (León)

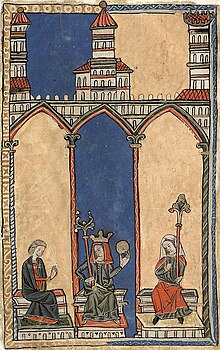

Urraca (* around 1080; † March 8, 1126 probably near Saldaña , Province of Palencia ) was a Queen of León , Galicia and Castile from the House of Jiménez from 1109 until her death . She was the first queen of medieval Europe to rule by her own birthright .

family

Urraca was the oldest and probably only child of King Alfonso VI. of León-Castile and his second wife Constance of Burgundy , who belonged to the French Capetian family . She was presumably born in late 1080 because her parents had not married before autumn 1079. She was raised in the household of the influential Leonese great Pedro Ansúrez , who was a close confidante of her father. In 1085 Alfonso VI conquered. the old Visigoth capital Toledo from the Moors back and established the precedence of León as the leading power on the Iberian Peninsula by adopting the dignity of a "God-appointed ruler over all nations of Spain" (Deo constitutus imperator super omnes Spanie nationes ) began.

The marriage of her parents had initiated a political and dynastic bond between the Leonese ruling house and the French house of Burgundy , which was to prove to be trend-setting for Urraca's biography as well as for the royal house itself. In 1087 her uncle, Duke Odo I of Burgundy , moved to Spain to fight the Moors. His entourage included his brother-in-law Raymond of Burgundy , to whom Urraca was probably betrothed that same year. After her uncle, King García of Galicia, died in 1090 after many years of imprisonment, she became the potential heiress of her father in the absence of any other male family members and her marriage to Raimund was concluded shortly thereafter. A few years later her cousin Heinrich von Burgund was married to her younger half-sister Theresia . Raimund was to by Alfons VI. appointed Count of Galicia , which provoked the resistance of the local nobility to this appointment of a foreigner; however, this rebellion was quickly broken. After the birth of the Infante Sancho Alfónsez in 1093, however, the prospects of Urracas and Raimunds to the throne diminished.

Around the same time, the Almoravids crossed from Africa to the Iberian Peninsula, which within a few years eliminated the fragmented Moorish Taifa kingdoms and thus formed a threatening Muslim power again. To secure the south-western border, Raimund was equipped in May 1093 with the territory south of Galicia around the cities of Santarém , Cintra and Lisbon , the area of the county of Portugal ; however, he lost Lisbon to the Almoravids the following year. In April 1097, Alfonso VI awarded. the county of Portugal to Henry of Burgundy, while Raimund had risen to a permanent and powerful member of the royal council. Urraca gave birth to two children during this time: Sancha (* before 1095) and Alfonso Raimúndez (* 1104).

The Alfonso VI family from León:

| Constance of Burgundy |

Alfonso VI King of León-Castile |

Jimena Muñoz | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Raymond of Burgundy Count of Galicia |

Urraca Queen of León-Castile |

Theresa "King of Portugal" |

Henry of Burgundy Count of Portugal |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Alfonso VII (Alfonso Raimúndez) King of Léon-Castile |

Alfonso I (Alfonso Enríquez) King of Portugal |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Succession to the throne

Between the years 1107 and 1109 Urraca's prospects for the successor to her father vanished completely until she was able to ascend the throne at the end of these two years. In May 1107, her half-brother Sancho was first designated by the father as the sole heir. In September of the same year Raimund died, which seemed to neutralize Urraca's interests at court in favor of those of her brother-in-law Heinrich von Portugal . Only the government in the county of Galicia was able to continue it in her name, as evidenced by the first document issued by her dated December 13, 1107, which designated her mistress of Galicia. On January 21, 1108, she confirmed herself in her possession as the "ruler of all Galicia" (tocius Gallecie imperatrix) . The death of her half-brother Sancho on May 29, 1108 in the Battle of Uclés unexpectedly placed her at the center of her father's considerations on the question of succession, as his eldest daughter she was now most likely to take on the role of potential heir to the throne.

Probably in August 1108 Urraca in Segovia was betrothed by her father to the King of Aragón , Alfonso I “the warrior” , which caused some problems. On the one hand, as second cousins, they were related to one another too closely by church standards ( Sancho III of Navarre was their great-grandfather together), which provoked the displeasure of the clergy under the leadership of the Archbishop of Toledo . On the other hand, the powerful Leonese-Castilian nobility was not enthusiastic about the rule of a foreigner. Furthermore, this marriage led to a deepening of the family gap between Urraca and her brother-in-law Heinrich of Burgundy, who had ambitions for reign in the kingdom for Urraca's still underage son, the Infante Alfonso Raimúndez. In May 1109 Urraca was officially proclaimed heiress by her father in the emblematic city of Toledo, the capital of the Visigothic predecessors, in the presence of "all the nobles and counts of Spain". Alfonso VI died on July 1, 1109. in Toledo and on July 22nd, 1109, one day after his burial, Urraca certified a privilege in favor of the Church of León as "Queen of all Spain" (Urraka dei nutu totius yspanie regina) . To confirm her sole rule, she expanded her title from 1110 to include the imperial character traditionally claimed by the kings of Léons in "Urraca, in God's grace Queen and Empress (Empress) of Spain ..." (Vrracha, Dei gratia regina et imperatrix Yspanie) .

Marriage and war with Aragón

Henry of Portugal had already distanced himself from the court shortly before Urraca came to power and consolidated his position in Portugal after a successful fight against the Moors. Urraca meanwhile moved to Monzón de Campos , where, despite the protests of the Archbishop of Toledo, she married Alfonso I of Aragon in October 1109. Her second husband had made a name for himself as the great warrior against the Moors, who had established Aragón as the second Christian power in Spain. At thirty-six, his marriage to Urraca was his first and was to be the only one of his life. After the wedding, Urraca accompanied her husband on a campaign against the ruler of Saragossa and was present on January 24, 1110 at the victory in the Battle of Valtierra . In May of the same year the couple moved to Galicia, where they crushed a revolt against their rule. The resistance of the Galician nobility was directed primarily against Alfonso I of Aragón and advocated the inheritance rights of the young Alfonso Raimúndez. But also between the spouses there was a break at this time, probably caused by Urraca's extramarital relations and Alfonso's violent temperament. She charged him with physical violence.

In the summer of 1110, Alfonso returned to Aragón alone to continue the war against Saragossa, whereupon Urraca could begin her independent government with the support of her nobility and clergy. Around the same time, the news arrived in León that the Pope had refused her marriage and urraca, under threat of excommunication, asked to separate from Alfonso. However, her husband was not ready to accept a separation and the associated loss of power and prepared for a power struggle with Urraca. Henry of Portugal, who hoped to gain his own power by defeating Urraca, allied himself with him. On October 26, 1111, Urraca suffered a first heavy defeat against her enemies in the Battle of Candespina, in which her lover, Count Gómez González , was killed. However, she managed to break up the opposing alliance by pulling Heinrich on her side by transferring the castles of Zamora and Ceia . Then she had her son proclaimed King Alfonso VII on September 19, 1111 in Santiago de Compostela , who was thus built up as a counter-pretender to Alfonso I of Aragón. However, then another of their armies at Viadangos suffered another defeat against Alfonso I of Aragón, who brought both Toledo and León under his control by the end of the year.

In the winter of 1111/12 Urraca consolidated their rule in Galicia and restored the morale of their followers. However, she had to pay for the alliance with her brother-in-law Heinrich by assigning further territories to him. In the spring of 1112 she went on the offensive and was able to lock her husband in Astorga . A decisive battle was not Urraca's intention; Instead, she used her military superiority to force a reconciliation with Alfonso I of Aragon, whom she still used as a counterweight to her brother-in-law Heinrich of Portugal, for whose future support she did not want to pay with further territorial cessions. Heinrich died in the summer of 1112, but his widow Theresia continued his energetic power politics for her son Alfonso Enríquez . In the summer of 1112 Urraca and the King of Aragón resumed their married life until Abbot Pontius of Cluny finally appeared as papal legate, who once again announced the annulment of the marriage by the Pope. After a few more deals, Alfonso "the warrior" returned to his own kingdom at the end of the year and Urraca was finally able to take over independent rule over León and Castile. In the spring of 1113 they drove the last Aragonese garrisons from Burgos , which was commented on with great satisfaction by the Muslim historian Ibn al-Kardabus , as the greatest defeat of the Moors of the time was inflicted by his own wife. However, she had to pay for these successes with the establishment of the family of her half-sister Theresia in the county of Portugal, who claimed an equal position towards her.

Troubled years

Urraca's further rule was characterized by constant internal unrest and numerous external battles. Alfonso I of Aragón continued to hold on to his claim to rule over Castile, her sister Theresa opposed her in secret, and especially south of the Duero there were repeated revolts by local nobles. Furthermore, Toledo was exposed to the raids of the Moors of Cordoba . In 1115, therefore, several campaigns were carried out in the area of Córdoba, in which, among other things, the governor of the Almoravids fell. In the spring of 1116, the powerful Galician Count Pedro Froilaz de Traba , who occupied Santiago de Compostela , rebelled . Urraca had to pull against him with army to bring the city back under their control. In order to stabilize the situation in Galicia, she allied herself with the influential Archbishop Diego Gelmírez . After moving to Sobroso , she was besieged there by the combined forces of her sister and Pedro Froilaz, whereupon she had to retreat to Santiago de Compostela.

In order to stabilize the border province of Zamora against the attacks of the Moors, Urraca settled the still young knightly order of the Hospitallers in León on June 3, 1116 by donating land in this region. She then took action against her former husband and successfully wrested control of Sahagún from him in August 1116 . In order to calm the subliminal opposition in Galicia, Urraca convened a council of their nobility and clergy in Sahagún. On behalf of her son, Diego Gelmírez opposed her and allied himself with the family of Pedro Froilaz and the Counts of Lara . By recognizing her eleven-year-old son in the formal rule over Galicia, Urraca was able to take the wind out of the sails of the opponents. And also with her former husband she came to a peaceful settlement towards the end of 1116 by making a peace with him in Burgos with amicable separation of property, with Alfonso I of Aragón renouncing all sovereign rights in León and Castile. Only the rulership rights over Burgos itself remained controversial, but this did not result in any armed conflicts, as Alfonso I of Aragón concentrated on the war against the Moors around Saragossa for the next few years . The most stubborn resistance to Urraca's government came from her half-sister Theresa, who had called herself “Queen of Portugal” in her documents since November 1117 and thus showed separatist aspirations.

When Urraca met Archbishop Diego Gelmírez in Santiago de Compostela in July 1117 for an interview, a popular uprising broke out, which was mainly directed against the episcopal city rule. The queen and the bishop were initially able to flee from the rebels in a newly built tower of the cathedral, which was then set on fire. While the archbishop was able to flee the city on unknown routes, Urraca had to face the angry crowd, who pelted her with stones and tore her clothes. She was saved by an approaching army of Count Pedro Froilaz, in whose wake her son was also. After the riot ended instantly, Urraca, despite her mistreatment, went mildly to court with the townspeople. Episcopal rule was restored and only the ringleaders were sentenced to exile and confiscated goods. Around the same time, the Almoravids attacked the county of Portugal and besieged Coimbra. Urraca immediately used her sister's distress to regain control over Zamora and Toro, which she had once had to cede to Henry of Portugal. She also succeeded in attracting some families of the Galician-Portuguese border aristocracy to her side, which further weakened her sister's position of power. As a result of the peace with Aragón, Urraca was able to restore her rule in the area south of the Duero and move into Toledo on November 16, 1117 with her son, who was proclaimed emperor over all of Spain.

Urraca's long-time confidante and fatherly friend, Count Pedro Ansúrez, died at the end of 1117. The Castilian Count Pedro González de Lara , who, as Urraca's lover, practically assumed the position of an unofficial prince consort, was installed in his position as first royal advisor . In addition to personal interests, this connection was also linked to solid political motives, because Urraca had thus secured an invaluable cornerstone of her power in Castile and thus against her former husband. On January 22nd, 1119, after a long struggle, he was finally able to conquer Zaragoza and win a decisive victory against the Moors. Urraca deepened her connection to the Lara household through the marriage of her half-sister Sancha to the brother of her lover, Rodrigo González de Lara . Against the growing influence of the Castilians at the royal court, a Leonese aristocratic frond arose in June 1119 under the leadership of Guter Fernández, the former royal majordomo. This captured Pedro González de Lara and besieged Urraca on July 18th in the castle of León. The differences between Urraca and their Leonese vassals could be settled in a compromise by September 1119. Since then, she has increasingly involved her son in government, who should rule primarily in Toledo, while Urraca now increasingly took care of matters in León and Galicia. In relation to her vassals, she received the support of Pope Calixtus II , a brother of her first husband, who in a letter of March 4, 1120 expressed his bitterness over the fragility of the vassals' loyalty to Urraca.

Consolidation of power

In the spring of 1120 Urraca's rule was so strong that she could finally go on the offensive against Theresa. In a military lightning operation, she advanced from Galicia to Portugal, crossed the Miño and routed the opposing forces at Tui . The retreating Theresa then besieged them in Lanhoso north of Braga . In July 1120, Urraca was able to move into Braga and there accept the submission of her nephew Alfonso Enríquez , whom she recognized as Count of Portugal, and the leading Portuguese nobility. She was able to end her sister's independent rule, which had existed since 1109, and put Portugal back under the sovereignty of the Leonese crown.

After she had been able to re-establish her power in Portugal, Urraca also intended to do the same in Galicia, where in previous years Archbishop Diego Gelmírez in particular had been able to expand his power and establish himself as a kind of counter-ruler. He and the Galician nobility allied with him made a secret pact with Theresa of Portugal against Urraca. In a letter dated June 1120, she warned the archbishop of the queen's next steps. On July 20, 1120, Urraca entered Santiago de Compostela and had the archbishop arrested immediately. So she ended the ecclesiastical rule over the city by occupying the towers of the city. However, this coup provoked a popular uprising, before which Urraca had to withdraw again into the protection of the cathedral. And when Count Pedro Froilaz recruited an army against her, which her own son also joined, she had to release the archbishop on July 28th to calm the situation. However, she did not reinstate him in the city rule, against which Pope Calixtus II protested sharply in five slices from October 7, 1120 to her, her son, the cardinal legate Boso, Archbishop Bernardo of Toledo and the entire Spanish clergy. In it she was threatened with excommunication and interdict over her kingdom if she did not reinstate the archbishop in his rule. Yielding to papal intervention, Urraca and her opponents began peace talks in November 1120. However, due to the uncompromising nature of both sides, these ran into the sand, whereupon Urraca advanced with army power to Galicia in the spring of 1121 and took up position near Santiago de Compostela. Archbishop Diego Gelmírez and Count Pedro Froilaz also raised an army against them, to which their son belonged again. After a few minor skirmishes, both sides were ready to hold peace talks in order to avoid greater bloodshed. Urraca had to recognize the archbishop again in all rights of rule over Santiago de Compostela; nevertheless, he continued to hold on to hostility towards them. In agreement with the papal legate Boso, he even carried out Urraca's removal and the enthronement of her son, on whom he exerted a great influence. On the other hand, Urraca had the support of Pope Calixtus II, who severely curtailed Diego Gelmírez's power within the church hierarchy by appointing the Archbishop of Braga to be the upper metropolitan over the dioceses of Portugal and Galicia and Archbishop Bernardo of Toledo to the primacy of the Church of all of Spain used. Bernardo von Toledo was a close confidante of Urraca, who successfully mediated a reconciliation between her and the sixteen-year-old Alfonso Raimundez, again to the detriment of the Archbishop of Santiago de Compostela.

Last years

Urraca's last six years of reign were largely calm. This time was mainly characterized by internal church disputes between the archbishops of Toledo and Santiago de Compostela over influence in the Spanish church hierarchy, with Urraca supporting her confidante Bernardo von Toledo. In May 1123, it was strong enough to arrest its constant rival in Galicia, Count Pedro Froilaz, and to confiscate his lands. This enabled it not only to decisively strengthen the power of the crown in Galicia, but also to weaken that of the Archbishop of Santiago de Compostela. Only Theresa was still a haven of resistance; it had fought for an independent territory in southern Galicia since 1121, with Tui as its center. However, Theresa was enemies with her own son, who in turn was recognized by Urraca as her obligated Count of Portugal. And the neutralization of her ally Pedro Froilaz put Theresia in place, whose Urraca family was able to bond with one of his sons by marrying their illegitimate daughter.

From 1124 onwards, Urraca gradually passed the reign to her son. First, under the advice of Archbishop Bernardo of Toledo, she left him rulership in the area south of the Duero, i.e. in Toledo. In a certificate issued on September 11, 1125 in San Pedro de las Dueñas , Alfonso VII called himself “King of Spain” (hispanie rex) for the first time , which apparently documents the expansion of his co-reign to the entire kingdom. Urraca died on March 8, 1126 near Saldaña on the Río Carrión at the age of 46. The credibility of the report from the Chronicon Compostelana , according to which she died as a result of a premature birth, is controversial in history. Alfonso VII was in Sahagún, thirty kilometers away, that day and immediately went to León the following day to receive the homage of the kingdom's vassals. Urraca was buried in the Abbey of San Isidoro in León , the expansion of which she had promoted.

Familiar

ancestors

|

Sancho III. of Navarre (990-1035) |

Munia Mayor of Castile (990-1066) |

Alfonso V of León (994-1028) |

Elvira Mendes |

Robert II of France (972-1031) |

Constanze of Provence (986-1034) |

Dalmas I of Semur | Aramburge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ferdinand I of Castile (1018-1065) |

Sancha of León (1013-1067) |

Robert I of Burgundy (1011-1076) |

Helie from Semur | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Alfonso VI of León-Castile (1040–1109) |

Constance of Burgundy (1045-1093) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Urraca (1080-1126) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

progeny

From 1087 to 1107 Urraca was married to Raymond of Burgundy for the first time , from which two children emerged:

- Sancha (* before 1095 - † February 28, 1159).

- Alfonso VII (March 1, 1105 - August 21, 1157), King of León and Castile.

Her second marriage to King Alfonso I of Aragon from 1109 to 1112 remained childless.

Urraca had two illegitimate children from her relationship with Pedro González de Lara :

- Elvira Pérez de Lara (* around 1117, † after 1174); 1. ∞ with García Pérez de Traba, Lord of Trastámara , 2. ∞ with Beltrán de Risnel.

- Fernando Pérez "Furtado" de Lara (* before 1123, † 1156).

literature

- Irene Ruiz Albi: La reina dona Urraca (1109–1126), cancillería y colección diplomática. León, 2003.

- Bernard F. Reilly: The Kingdom of León-Castilla under Queen Urraca. 1109-1126. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1982, ISBN 0-691-05274-3 ( online ).

- Bernard F. Reilly: The Medieval Spains. 10th printing. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-39436-9 .

- Therese Martin: The Art of a Reigning Queen as Dynastic Propaganda in Twelfth-Century Spain. In: Speculum. Vol. 80 (2005), pp. 1134-1171.

Remarks

- ↑ See Reilly (1988), § 10, p. 192.

- ↑ Alfonso VI: Cancillería, curia e imperio II, Colección diplomática, ed. by Andrés Gamba in: Fuentes y Estudios de Historia Leonesa. Vol. 63 (1998), pp. 136-137.

- ↑ See Reilly (1988), § 10, p. 194.

- ↑ Chronica Gothorum, ed. by Alexandre Herculano in Portugaliae Monumenta Historica, Scriptores 1 (1856), pp. 10-11.

- ^ Antonio López Ferreiro: Historia de la Santa AM Iglesia de Santiago de Compostela. Vol. 3 (1900), Appendix No. 25, pp. 75-76.

- ↑ Archivo de la Catedral de Lugo, Tumbo viejo, folio 16r – 17.

- ↑ Ibn Challikan , Wafayāt al-aʿyān wa-anbāʾ abnāʾ az-zamān, In: The Image of Alfonso VI and His Spain in Arabic Historians, ed. by Tom Drury. Princeton University, 1974, p. 326.

- ↑ Las crónicas anónimas de Sahagún, ed. by Julio Puyol y Alonso in: Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia. Vol. 76 (1920), § 14, pp. 120-121.

- ↑ Colección documental del Archivo de la Catedral de Léon (775-1230), Vol. 5, ed. by José María Fernández Catón in: Fuentes y Estudios de Historia Leonesa, Vol. 46 (1990), No. 1327, p. 3.

- ↑ See Ruiz Albi (2003), pp. 371–373.

- ↑ Las crónicas anónimas de Sahagún, ed. by Julio Puyol y Alonso in: Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia. Vol. 76 (1920), § 17, p. 122.

- ↑ Las crónicas anónimas de Sahagún, ed. by Julio Puyol y Alonso in: Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia. Vol. 76 (1920), § 18, pp. 242-244.

- ↑ Historia Compostelana, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 20 (1765), p. 116.

- ↑ Las crónicas anónimas de Sahagún, ed. by Julio Puyol y Alonso in: Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia. Vol. 76 (1920), § 20, p. 246.

- ↑ Annales Complutenses, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 23 (1767), p. 314.

- ↑ Charles Julian Bishko: The Spanish Journey of Abbot of Cluny Ponce. In: Ricerche di storia religiosa. Studi in onore di Giorgio La Piaña. Vol. 1 (1957), pp. 311-319.

- ↑ Ibn al-Karadabus, Historia de al-Andalus, ed. by Felipe Maíllo Salgado in: Akal Bolsillo 169 (1986), pp. 140-141.

- ↑ Historia Compostelana, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 20 (1765), pp. 211-215.

- ↑ Historia Compostelana, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 20 (1765), pp. 216-217.

- ^ Cartulaire general de l'ordre des hospitaliers de Saint Jean de Jérusalem, 1110-1310. Vol. 1, ed. by Joseph Delaville Le Roux (1894), p. 34.

- ↑ Las crónicas anónimas de Sahagún, ed. by Julio Puyol y Alonso in: Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia. Vol. 77 (1920), § 70-71, pp. 53-59.

- ↑ Historia Compostelana, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 20 (1765), pp. 221-226.

- ↑ Las crónicas anónimas de Sahagún, ed. by Julio Puyol y Alonso in: Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia. Vol. 77 (1920), § 73, pp. 155-156.

- ↑ Documentos Medievais Portugueses, Dosumentos regios. Vol. 1, ed. by Rui Pinto de Azevedo (1958), No. 48-49, pp. 59-60.

- ↑ Historia Compostelana, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 20 (1765), pp. 227-249.

- ↑ Anales toledanos I, ed. by Ambrosio Huici y Miranda in: Las crónicas latinas de la reconquista. Vol. 1 (1913), p. 345.

- ↑ See Reilly (1982), § 12, p. 362.

- ↑ Historia Compostelana, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 20 (1765), p. 270.

- ↑ Historia Compostelana, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 20 (1765), p. 316. Calixti II papæ epistolæ et privilegia , ed. by Jacques Paul Migne in, Patrologiae cursus completus. Series Latina. Vol. 163, Col. 1171.

- ↑ Historia Compostelana, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 20 (1765), pp. 324-327.

- ↑ História de Portugal III , ed. by Luiz Gonzaga de Azevedo (1940), pp. 123-125.

- ↑ Historia Compostelana, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 20 (1765), pp. 327-330.

- ↑ Historia Compostelana, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 20 (1765), pp. 332-335.

- ↑ Historia Compostelana, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 20 (1765), pp. 341-346. Calixti II papæ epistolæ et privilegia , ed. by Jacques Paul Migne in, Patrologiae cursus completus. Series Latina. Vol. 163, Col. 1220-1221.

- ↑ Historia Compostelana, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 20 (1765), pp. 346-349.

- ↑ Calixti II papæ epistolæ et privilegia , ed. by Jacques Paul Migne in, Patrologiae cursus completus. Series Latina. Vol. 163, Col. 1222-1223 and 1299-1300.

- ↑ Historia Compostelana, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 20 (1765), pp. 381-385.

- ↑ Catálogo del archivo del monasterio de San Pedro de las Dueñas, ed. by José María Fernández Catón (1977), p. 20.

- ↑ Chronica Adefonsi Imperatoris, ed. by Luis Sánchez Belda (1950), pp. 4–5. Historia Compostelana, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 20 (1765), p. 432.

- ↑ Chronicon Compostelana, ed. by Enríque Flórez in: España Sagrada. Vol. 20 (1765), p. 611. See Reilly (1982), § 6, p. 201.

Web links

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Alfonso VI |

Queen of León Queen of Castile Queen of Galicia 1109–1126 |

Alfonso VII |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Urraca |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Urraca de León y Castilla |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Queen of Castile, Galicia and Leon |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1080 |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 8, 1126 |

| Place of death | unsure: Saldaña , Province of Palencia |