Contemporary knowledge of the Holocaust

The contemporary knowledge of the Holocaust became a special research topic in contemporary history from the 1990s . According to the unanimous assessment of the more recent research, the frequently made statement by the Germans in the post-war period that they knew nothing about the Holocaust represents a protective claim . In fact, the mass murder of the Jews of Europe was an open secret that one might well have known. Instead, many would have deliberately looked the other way.

Pre-war period (first signs of persecution)

The Nazi regime's greatest instrument of power was the concentration camp system , which was set up immediately after taking power in 1933. The SA's “wild” concentration camps did not last long. In many parts of the German Reich, the population saw that numerous prisoners had been released.

The SS concentration camps existed for years. The SS controlled the prisoner mail . Many of the Nazi camps were located close to localities, so that their residents got some insight into the processes of a concentration camp. The slogan that was to be read at the entrance gates of many concentration camps (“ Work makes you free ”) was intended to suggest the possibility of release from a concentration camp. In the early years, for propaganda and appeasement purposes, there was an “open day” in the Dachau concentration camp . As a Potemkin village, the “showcase camp” was supposed to give the most positive impression possible. Initially, some Reich Germans were allowed to enter the SS concentration camps, for example as suppliers of goods. In later years the concentration camps were strictly shielded.

Even in the early years of the concentration camp, the SS treated Jewish prisoners significantly worse than most other concentration camp inmates.

The expropriation (" Aryanization ") of Jewish property made many Germans and Austrians direct or indirect beneficiaries of a partial step on the way to the Holocaust. The question of what should happen to the expropriated Jews, who are now in many cases unable to leave the country , has been a general question, particularly since the November pogroms in 1938 . The Nazi newspapers reacted to this with increased anti-Semitic propaganda , which prepared further steps such as the establishment of ghettos and camps in the east.

Kurt Scharf , later State Bishop of Berlin-Brandenburg, described the beginnings of the persecution of the Jews:

“In Berlin you experienced that on a large scale. As early as 1932 there were swastika graffiti on Kurfürstendamm, then in 1938 the burning synagogues, the smashing of Jewish shops - the so-called Kristallnacht: All of Germany knew that. Goebbels and Streicher announced this on the radio, and it was shown in the newsreels of the film theaters. (...) We saw the assembly camps on Oranienburger Strasse in Berlin, where the Jews were rounded up. (...) The theory of the master race was spread in every newspaper. "

Wartime

Knowledge of extermination sites (industrialized gassing and cremation)

The so-called final solution to the Jewish question remained hidden from most of the Reich Germans and was mostly unimaginable even for those who had heard about it via foreign broadcasters or reports from soldiers. Events such as the Wannsee Conference or the Korherr Report were classified as "secret Reich matters" and subject to the highest level of secrecy . Historians therefore do not assume that there was an overall knowledge of the extent and implementation of the Holocaust at that time.

Victim knowledge

Reports from escaped prisoners

Isolated prisoners managed to escape from extermination camps and pass on information. In April 1943 Witold Pilecki managed to escape from Auschwitz-Birkenau; his reports were sent to resistance movements and governments (Pilecki reports) . Rudolf Vrba and Alfréd Wetzler fled in April 1944 and then provided information about the extermination camp and the preparations for the murder of the Jews from Hungary (Vrba-Wetzler report) . Also Jan Karski informed in 1942 after he - disguised as a Trawniki man - had become the eyewitness of industrialized extermination camps (July 1943 meeting with Roosevelt ). In post-war trials, some of these reports became official Allied documents ( Auschwitz Protocols ) .

Reports from Holocaust survivors

Holocaust survivors reported in the post-war period that the victims who were directly affected did not suspect their impending fate or did not want to believe the rumors about industrialized extermination factories:

“The murder of millions of people, planned with bureaucratic thoroughness and carried out in the factory - this unprecedented dimension of crime overwhelmed the imagination of even those who believed the Nazis could do all kinds of outrages. To think the unthinkable, to consider Auschwitz to be real - a psychological self-protection reflex resisted this. This also applied to the designated victims, especially the Jews of Western Europe. Until the very end, they did not consider the Germans capable of such a crime ... "

Konrad Löw wrote in 2007 in the FAZ :

“It is even more difficult to judge the true facts when one realizes that even numerous Jewish victims adamantly assert their ignorance. The Auschwitz refugee Friedemann Needy believed he knew that those arriving in Auschwitz not only had no idea where they were, but also not the slightest bit of what was intended for them. They did not allow themselves to be led to the slaughter almost without resistance because of their 'racial inferiority', as the Nazis liked to claim, but because they did not even know that they were going there. "

Löw accused historians such as Peter Longerich , Saul Friedländer , Ian Kershaw and others. a. propose to ignore such statements from Jewish sources in their investigations on the subject.

In his speech to the Bundestag in January 2012, the Holocaust survivor Marcel Reich-Ranicki reported about the imminent "resettlement" of the Warsaw ghetto that the Warsaw Jews did not know what was coming in the summer of 1942, namely the deportation to Treblinka :

“On the same day, on July 22, 1942, the Jewish security service , which had to carry out the resettlement operation under the supervision of the ' Judenrat ' , was supposed to bring 6000 Jews to a place on a railway line, the Umschlagplatz . From there the trains departed to the east. But nobody knew where the transports were going, what was in store for the 'resettlers'. "

On April 19, 1943, the uprising began in the Warsaw Ghetto . On the same day there was an attack on the 20th deportation train to Auschwitz in Belgium . Robert Maistriau , one of the participants in the action, later reported:

“I was surprised by the tremendous silence at that moment. I went to the train and stood right in front of a carriage. I took my tools and opened the door. I faced about 50 people who were all silent. "

More than 60 joint plaintiffs were admitted to the Lüneburg Auschwitz Trial in 2015, which involved the so-called Hungary Action from summer 1944. Both the defendant Oskar Gröning and the joint plaintiff reported that the selections in Birkenau had passed off quietly because the arriving deportees were “completely clueless”. Photos of the Auschwitz album published in 1980 also show how the Hungarian deportees waited innocently in front of a gas chamber.

German Empire

Perpetrator knowledge

For high-ranking NSDAP functionaries and employees of the NS authorities, the intention to exterminate the Jews from autumn 1941 was expressed almost openly. At the latest since the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, the upper levels of the ministries and Nazi authorities had been informed of the plans for the deportation of millions of Jews to labor and extermination camps. The conference participants were aware that the “final solution” meant annihilation, as the conference planner and recorder, “Jewish advisor” Adolf Eichmann, testified in his 1961 trial in Israel . In the second of his “ Posener Speeches ” Heinrich Himmler said to the assembled Gau and Reichsleiter on October 6, 1943:

“The sentence 'The Jews must be exterminated' in its few words, gentlemen, is easy to pronounce. For those who have to do what they ask, it is the hardest and most difficult thing there is. […] You now know and you keep it to yourself. Perhaps in a very later time one will be able to consider whether to tell the German people a little more about it. I think it is better that we - we as a whole - have carried this for our people, have taken responsibility (the responsibility for an act, not just an idea) and then take the secret with us to our grave. "

The Jewish officer in the Foreign Office, Franz Rademacher , wrote to the personnel department in his business travel statement: “Type of official business: Liquidation of Jews in Belgrade”. On the basis of such evidence, the Independent Commission of Historians - Foreign Office decided in 2010 that the Foreign Office had paved the way for the "Final Solution" and was an active supporter of the deportation of Jews and even the extermination of Jews: "Those who knew about it were also accomplices."

Observer knowledge

Train drivers of deportation trains and other railway employees came into the immediate vicinity of the industrialized extermination sites.

The Erfurt-based company Topf and Sons , originally furnace builders, was involved in the construction, commissioning and maintenance of incinerators and the ventilation system for gas chambers in Birkenau. Several employees known by name stayed in Auschwitz for days. They saw construction plans and installed the ventilation system and the crematorium ovens .

Information policy

Nazi press reports

At the same time, the Nazi information policy, with general hints in newspaper and weekly news reports that suggested the organized extermination of the Jews, deliberately created a kind of knowledge of the Germans. In speeches broadcast throughout the Reich , Adolf Hitler openly spoke of the "annihilation" of the Jews, which he had "prophesied" on January 30, 1939, in the event of a new world war. Up to 1943 he came back to this more often - five times in 1942 alone - in identical wording: Of the Jews who used to laugh at him for his “prophecy”, many would no longer laugh now; soon, according to Hitler, none of them would laugh anymore. The German press also often mentioned these speeches. According to Saul Friedländer, many listeners whose diary entries noted the speeches understood that Hitler was referring to the ongoing extermination of the Jews : among them the Osnabrück bishop Hermann Wilhelm Berning , to whom the execution of Hitler's intention to exterminate in February 1942 was clear.

In an article in the NSDAP daily newspaper Danziger Vorposten on May 13, 1944, written by Wilhelm Löbsack , head of regional training , it was said that Judaism had “suffered further heavy losses” and that “core areas of Jewish concentration” in Poland and now Hungary had been “neutralized” ”And“ five million Jews turned off ”.

Oral reports

Since the first wave of vacation for Wehrmacht soldiers following the attack on Poland in the winter of 1939/40, more and more details about what was going on in the areas occupied by the Wehrmacht leaked out. Germans involved in mass shootings reported this to their relatives in letters or during their home leave. In connection with the press releases, the “ whispering propaganda ” gradually gave more and more precise ideas of what was happening to Jews “in the East”. The deportations from major German cities, which began in October 1941, took place in public at assembly areas and train stations and were often accompanied by large numbers of onlookers. The establishment of ghettos and large camps was also announced publicly in Germany. For most Germans, however, their purpose was disguised and disguised with the typical Nazi camouflage language. The transports there were referred to as “resettlement” or “evacuation” and were accompanied by intense propaganda. German Jews were described as " enemies of the people ", criminals or allies of the war opponents, who accordingly deserved no "preferential treatment". Many residents of the Westphalian city of Minden , for example, had known since the end of 1941 that terms like “resettlement” meant mass executions . Ruth Andreas-Friedrich wrote in her diary on December 2, 1942:

“The Jews go into hiding in droves. Terrible rumors are circulating about the fate of the evacuees. From mass shootings and starvation, from torture and gassings. "

The flow of information about the murders of the Einsatzgruppen and the crimes of the Wehrmacht reached such a level in 1942 that the government took action against it using the means of political criminal law. In doing so, it relied on the Dodge Act of 1934 and the Special War Criminal Law Ordinance of 1938. The passing on of correct information was threatened with imprisonment or “ protective custody ” as “insidious dissemination of atrocious lies ” . However, many proceedings were also not initiated in order to keep the secret with which the Nazi regime surrounded the mass killing in the east. A public prosecutor at the Stuttgart Special Court, for example, dropped a case against a citizen with knowledge of massacres in Poland on the grounds: "What was said about the treatment of Jews is likely to be unsuitable for public discussion." In March 1945, soldiers who reported had passed on the Holocaust, executed.

Mood reports

Since the defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad in early 1943 and the Allied air raids on German cities, open anti-Semitic propaganda has receded somewhat, as it has now met with increasing lack of understanding and displeasure in parts of the population, which the Gestapo registered. The attempt to pass the Katyn massacre off as the Soviet Union's intention to exterminate all Germans failed: According to reports from the Reich in which the security service of the SS (SD) summarized the surveillance and mood reports , "a large part of the population" the excitement about Katyn as "hypocritical, because on the German side Poles and Jews were eliminated on a much larger scale". The level of knowledge of individual persons becomes clear through judicial and police files, diaries and letters. A numerical statement of how many people had certain knowledge or detailed knowledge cannot be derived from this.

Information booth through foreign media

"Enemy transmitter"

From July 1942, the BBC broadcast details of the extermination of the Jews, regularly also in German. An early report gave the first figures without concluding that there was an intention to exterminate:

“An international commission gives the following figures. In Germany, of the 200,000 or so Jews who were there in 1939, at least 160,000 were abducted or perished. In Austria there are no more than 15,000 of the 75,000 Jews, in Bohemia and Moravia, where there were also 80,000 Jews, there are now around 10,000. "

Thomas Mann mentioned the murder of Jews many times in his BBC speeches, as early as November 1941, together with the crimes of killing the mentally ill, Serbs and Poles. Poison gas is mentioned for the first time in the January 1942 broadcast, and in September 1942 Mann speaks of mass killings using poison gas and of the "maniacal decision to completely eradicate European Jews".

Listening to " enemy broadcasters " was considered a broadcast crime , was strictly forbidden in the German Reich and was punishable by the death penalty. For example, in September 1942, the People's Court sentenced Walter Klingenbeck, a teenager, to guillotine death.

Nevertheless, listening to foreign stations was widespread. Most of the audience, especially after 1943, was interested in the front lines. Since such reports were often mixed with propaganda against the German warfare, their credibility for the Germans and Austrians was not always recognizable.

pamphlets

Among the millions of leaflets thrown over German territory by the Allies was a text by the White Rose , which tells of the murder of 300,000 Polish Jews, the most terrible crime that no similar crime can stand alongside in the whole of human history .

Other

The English Daily Telegraph published for the first time on June 25, 1942 a number of victims in Kulmhof (Chelmno) by gas (carbon monoxide) of approx. 40,000 for Dec 1941 through March 1942 at a murder rate of 1,000 per day.

Occupied territories, collaborators, foreign workers

The Nazi crimes would have been impracticable without the concentration camps as an instrument of power and without a large army of German and non-German helpers. In many cases, the Nazi regime was able to fall back on collaborators who, for example, took action in the Baltic States to track down Jews, to extradite them or to murder them themselves. In Hungary the Horthy regime, together with the Eichmann Kommando, brought about the ghettoization, disenfranchisement and plundering and the deportation of over 400,000 Hungarian Jews in spring 1944.In autumn 1944 it was the Arrow Cross regime that terrorized the remaining 100,000 Jews in Budapest.

In the Trawniki forced labor camp , which was later subordinated to the Majdanek extermination camp , the SS trained foreign helpers. Often these were referred to as "Trawniki men". Most of them were Ukrainians, but also Latvians, Estonians, Lithuanians and Poles.

Allies

State of information from foreign governments

The British foreign intelligence service , the Secret Intelligence Service, deciphered the coding of radio messages from the German police - not from the SS and SD - in September 1939. In the following year, British and French eavesdropping specialists deciphered almost all radio messages intercepted by the German police battalions in the occupied territories of Poland, even after their code had been changed has been. As a result, they learned early on of forced resettlements and executions in the Generalgouvernement .

In August 1941 the Germans changed the code of police reports in the occupied Soviet territories again. Nevertheless, by then the British were able to intercept and decipher around half and then a quarter of all police radio messages. They realized that disguise terms like “special task” meant mass murder . They learned of thousands of mass executions by the Ordnungspolizei and the Waffen SS behind the Eastern Front, which had to be reported to the higher SS and police leaders.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill received daily short reports and weekly summaries of deciphered German police reports. In his radio speech on August 24, 1941, he announced parts of this knowledge for the first time:

“The attacker is surprised, amazed and shocked. For the first time he is experiencing that mass murder is not worthwhile. He avenges himself with the most terrible acts of violence. Where his armies advance, the population of whole areas is wiped out. Hundreds of thousands - really hundreds of thousands - of executions are being carried out; German police forces cold-bloodedly murder Russian patriots who are defending their fatherland. [...] We are witnessing a nameless crime. "

He named only one group of perpetrators, but not the Jews as the main group of victims, and interpreted the murders as acts of revenge on Soviet war successes in the context of fighting.

From the German double agent Paul Thümmel , who also worked for the Czechoslovak intelligence service , the British learned of mass shootings of male Jews in Ukraine by Wehrmacht soldiers at the end of July 1941 . Since August 28, 1941, the intelligence reports to Churchill also contained clear references to Jews as victims and the numbers of those murdered with increasing frequency and tendency. On September 12, the summary report to him concluded:

"[...] the numbers offer [...] revealing indications of a policy of cruel intimidation, if not total annihilation."

On the same day, the British Secret Intelligence Service announced that it would no longer separately mention any material about the murders in its reports to Churchill, unless it was expressly requested: “By now it should be well known that the police [in the Soviet Union] everyone Kills Jews who fall into her hands. ”Just one day later, on September 13, Kurt Daluege forbade the higher SS and police leaders to broadcast execution numbers. Both likely reacted to Churchill's August speech. The British were concerned about losing their source of news when the Germans checked their radio encryption methods. In addition, the British were now primarily interested in information about the course of the war. Nevertheless, they continued to learn of executions disguised as “post-war actions” and of the cooperation between the SS, police and armed forces.

A secret report by the Ministry of Information of January 22, 1942 made it clear on the basis of regularly evaluated press reports and censored private mail from all over Europe:

"The Germans are clearly pursuing a policy of exterminating the Jews."

Now the allies became aware of the Holocaust that had begun in ever greater detail. This knowledge, gradually made up of many individual parts, was initially hardly taken seriously by the governments and then passed on to the public only reluctantly.

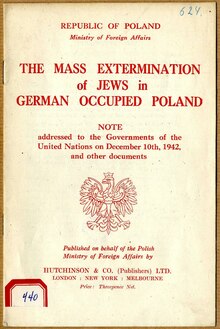

From spring to autumn 1942, information from the American and British governments about the Holocaust to the Polish and many Jews deported from Western Europe, the Aktion Reinhardt , which began in March 1942 with the "liquidation" of the first Polish ghettos . The Grojanowski Report , the Riegner Telegram and the report of the Polish underground fighter Jan Karski should be mentioned here . In November 1942, after Karski's report on regular extermination camps seemed to confirm previous reports, pressure increased on the Allied governments to publicly condemn the murders, leading to the December 1942 International Declaration on the Extermination of the Jews . Concrete steps to wake up the German public or to exert pressure on the National Socialists through other measures, such as the involvement of the neutral states, were largely omitted. Only the BBC (under the direction of the Political Warfare Executive ) undertook an information campaign which led to the spread of knowledge about the Holocaust among the German population.

Information level of the foreign population

In November 1941 Richard Lichtheim , representative of the Jewish Agency for Palestine in Geneva, reported to Chaim Weizmann , the President of the Jewish Agency : Entire trains with German, Austrian and Bohemian-Moravian Jews went to Litzmannstadt (Polish: Łódź ) and from there unknown places further east, probably as far as Minsk . He urged Weizmann to make this known worldwide. At the urging of Gerhart Riegner , a German-Jewish lawyer who fled to Switzerland in 1933, the World Jewish Congress sent a report to the British Foreign Office in February 1942, which precisely documented the persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany from February 1933 to November 1941 on 160 pages.

Surveys carried out in the USA during the war show that the Holocaust was in many cases not believed even by the US population informed by free media until the end of 1944: The extent of the Holocaust made it easier to camouflage ...

The Maidanek extermination camp in eastern Poland was the first Nazi camp to be captured by the Allies in July 1944. A few days after the conquest by the Red Army , the British journalist Alexander Werth , correspondent for the London Sunday Times and the BBC, visited the camp. He wrote a report for the BBC describing the camp as a death camp where people were gassed. However, the BBC refused to air the report because it suspected a Soviet progaganda lie. Only after the liberation of Buchenwald, Dachau and other camps on the western front in April 1945 were Werth's reports accepted as accurate.

Knowledge of mass shootings

Information status of the population in the German Reich

Anyone involved was strictly prohibited from communicating about the mass murders behind the Eastern Front. There were witnesses from the military units stationed there. Some soldiers stationed on the Eastern Front took pictures of the mistreatment and executions of individual Jews with private cameras, which appeared in some private photo albums.

In 1943, Graf von Moltke , who was brought to resistance against National Socialism by the persecution of the Jews , wrote:

"At least nine-tenths of the population does not know that we killed hundreds of thousands of Jews ... They still have the idea that the Jews were only marginalized and now lived on in the East in a similar way as they did in Germany."

In the last two years of the war, Nazi magazines published clearer details for party and regime members. The previous secrecy policy on the part of the Wehrmacht was relaxed, and in 1943 there was a real "execution tourism " ( Ernst Klee ) of perpetrators who wanted to watch a mass shooting. However, the extermination camps were still shielded.

Regional Bishop Theophil Wurm wrote on September 21, 1944 to a pastor of the German Christians : Everyone knows or can know how the Third Reich dealt with the Jews, especially since the night of November 9th to 10th, 1938 and during the war up to the complete Extermination outside in Poland and Russia. It should also not be unknown that in the occupied territories serious injustice has been committed against completely innocent people through the reintroduction of the hostage system that was customary in barbaric times. Then I remember the systematic murder of the mentally ill and the whole system of the Gestapo and the concentration camps, the fact that there is no longer an independent judiciary ... I just ask: Can a Christian hope for blessings for a people who have all this make it happen ...?

Franz Josef Strauss wrote in his memoirs that as a Wehrmacht soldier he had witnessed mass shootings of Jews in the East on several occasions.

The diary of the Celle engineer Karl Dürkefälden , which has been kept since 1938, shows that as a private person it was possible to obtain information about the murder of Jews at the time. He was opposition and wrote down personal impressions, questioned colleagues, acquaintances and relatives; he distrusted the official news and took risks by listening to enemy broadcasts . In February 1942 Dürkefelden overheard a German soldier talking about mass extermination in the east while on a train journey. Shortly afterwards he read in the Lower Saxony daily newspaper that Hitler had announced the extermination of the Jews. These two fragments led him to his own conclusion: The Jews are being systematically exterminated. In June 1942, personal reports from his brother-in-law and his employer of mass executions near Kiev and Białystok confirmed him. Further reports from soldiers on home leave came in the summer. In the autumn of 1942 Dürkefälden heard a German-language BBC broadcast with figures on mass murders of Jews. This year he realized that the deportations of the Jews were aimed at their extermination, without having to be at the front or in the vicinity of Nazi camps. From a soldier stationed in Vilnius who had previously been an employee of his company, he also learned in January 1943 that "the Jews from France and other occupied countries were being brought to Poland and some of them were shot and some were gassed". From this he combined a relatively precise picture of the dimensions of the murder of the Jews, even without finding out anything about the death factories themselves.

By evaluating intercepted conversations among Allied prisoners, it has been known since 2011 that the Holocaust in all its forms was known to most Wehrmacht soldiers. Observers told their comrades in detail about mass shootings, about the problems of the shooters with "overexertion" when killing, especially of small children, from gas vans , about corpses being burned during Operation 1005 . In many cases, soldiers and residents were invited by SS officers to watch, so that “execution tourism” came about.

Information level of the foreign population

Since October 1941, British newspaper readers learned of individual German mass murders of Jews from Eastern Europe, about 45,000 deported Jews from Zhitomir , pogroms against thousands of Jews in the Ukraine and about 6,000 murdered Jews from Czyżew in eastern Poland . These reports reached the British public mainly through the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA) , the Polish government in exile and individual Eastern European correspondents.

The London newspaper The Jewish Chronicle reported on its front page on October 24, 1941, under the headline Ghastly Pogroms in Ukraine (“Horrible Pogroms in Ukraine”) about the Kamenets-Podolsk massacre , in which tens of thousands of Jews were deported for the first time and then shot . The report referred to statements by Hungarian officers about the murder of 15,000 Jews who had previously been deported from Hungary to Galicia. The editors did not comment on the report, possibly because the reports were unconfirmed.

On October 26, 1941, the New York Times reported on a massacre of “German soldiers” and “Ukrainian bandits” of Galician Jews and Jewish deportees from Hungary with 8,000 to 15,000 victims. This crime was reported in letters from Galicia to recipients in Hungary, as well as by Hungarian officers who were eyewitnesses. The report named the Kamenets-Podolsk region as the scene of the crime and August 27 and 28 as the time of the crime.

Hannah Arendt , expatriated by the National Socialist regime in 1937, has published mainly on the Holocaust since 1943. She wrote in late 1944 in their American exile the article Organized guilt :

“While the crimes, which have been part of the daily routine in the concentration camps since the beginning of the regime, used to be a jealously guarded monopoly of the SS and the Gestapo, now any Wehrmacht members are assigned to the mass murders . The reports about these crimes, which were initially kept as secret as possible [...], were only distributed via whisper propaganda staged by the Nazis themselves, and they are now openly admitted by them as liquidation measures in order to avoid those ' national comrades ' who For organizational reasons, one was unable to join the ' national community ' of the crime, at least to be pushed into the role of confidante and accomplice. "

post war period

Allied confrontation of the population

After the end of the war , the Allies confronted the population of the German Reich with the deeds of the dictatorship. H. with the consequences of consenting to the Nazi regime.

For example , the US commandant of Weimar, a representative of the US occupation forces, persuaded Weimar residents to visit the liberated Buchenwald concentration camp on April 16, 1945 in order to obtain ration cards. War correspondent Margaret Bourke-White wrote that during the visits women fainted and men turned their faces away. There had been disputes with former concentration camp prisoners who accused the residents of Weimar of knowing the conditions in the concentration camp: you knew it. (...) We worked next to you in the factories. We told you and we risked our lives. But you didn't do anything.

The population in the vicinity of Dachau and Munich was confronted in a similar way. The Nazi propaganda had presented the Dachau concentration camp and the Theresienstadt camp as “model camps” (see also: Dachau concentration camp in the National Socialist press ) and published seemingly harmless photos showing inmates, for example, ice stock sport. The population now got access to the concentration camp area and was asked by US troops to z. B. to look at the corpses of the death train from Buchenwald or to walk past the exhumed corpses.

Atrocity films (“atrocity” films) about Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen and Dachau were shown to the population . Volker Ullrich described the reactions of the audience: Most of them reacted with a terrifying emotional rigidity.

The Soviet allies used propaganda to spread an inflated death toll. Up until the beginning of the 1990s, the Auschwitz memorial could read that four million people had been murdered in Auschwitz. Mikhail Gorbachev turned the Soviet Union around with glasnost (transparency) and perestroika (restructuring). After the change in the political system in the Eastern Bloc, not only did the Berlin Wall fall , but they also corrected their excessive death toll to the current state of historical research of 1.1 to 1.5 million deaths in Auschwitz . The excessive number of Soviet propaganda lies had served Holocaust deniers as an opportunity to question the entire Nazi extermination machine.

After the Federal Republic of Germany was founded in 1949, politicians such as Theodor Heuss , Richard von Weizsäcker and Helmut Schmidt declared that they had no knowledge of the Holocaust. Schmidt said that he had neither heard of the “Reichskristallnacht” nor saw a Jewish star. In an interview with the FAZ in April 2005, when asked when he first had an idea that the National Socialists were criminals: "After the war [...] I didn't know anything about the genocide against the Jews, how." many people back then. ”When asked that they knew there were concentration camps, Schmidt referred to the industrialized killing sites :“ I didn't know anything about them, neither did my father. ”On the reference to the Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg and Bergen-Belsen said to Schmidt: “My father and also my in-laws, the Jews hid - not permanently, only for one night on the floor and one night in the basement, and a few days later someone else came for one night - we didn't know anything about it. "

Confrontation through Nazi trials

Albert Speer protested in the Nuremberg trial against the main war criminals, like other accused Nazi perpetrators, of ignorance of the Holocaust. He tried to make this believable until the end of his life. He was subsequently burdened by new finds of documents: He himself drove forward the expropriation of Jews, benefited personally from it and approved deliveries of building materials for the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp . He had always denied having been present at Himmler's Posen speeches, although Himmler spoke to him directly once according to the manuscript of the speech. Since Speer was in close contact with listeners who then came to see him, it is “simply impossible” that he did not find out about it.

Historical research

Recent research

For decades, research into the knowledge of Germans about Nazi crimes was hampered by the systematic destruction of files by the Nazi regime, ongoing psychological defense mechanisms, the increasing time lag and the decrease in authentic witnesses. In addition, historians usually do not consider their own perception to be a source of equal importance to written and other documents.

In surveys of the Allies from 1945 onwards, many Germans replied stereotypically that they had no knowledge of the Nazi mass murders. Observers at the time saw this as a protective claim that was intended to ward off a feared punishment, or as repression. US intelligence services and psychologists gained their experience with interrogated Germans in the final months of the war. However, the interrogation protocols of the Allied armies were not published until decades later. They and the secret reports by Nazi authorities, which were also published late, formed the starting point for more recent research.

Hans-Ulrich Wehler summarized the state of research up to 2003 in such a way that the secrecy had been successful insofar as a large part of the population had no precise information about the Holocaust. Nonetheless, in addition to the hundreds of thousands of accomplices and eyewitnesses, several million Germans must have “got to know the thrust of the Holocaust, even if not its full extent”.

As early as 1995, the Israeli historian David Bankier published his systematic analysis of interrogations by the US Army. He described their unequivocal result as a "secret that has not remained": Almost every German had some knowledge of the Nazi crimes towards the end of the war. The method of gassing was also a topic of discussion in "wide circles". Many respondents said they were relieved to be able to speak freely about it for the first time. The interrogators observed that "there was a strange feeling of guilt about the Jews in the foreground", "an uncomfortable mood and often an open admission" of a "great injustice". Banker's verdict followed in 2006 with Peter Longerich, Frank Bajohr and Dieter Pohl, as well as some German historians. Longerich tried to capture the distribution and content of the knowledge of Germans about the Holocaust more precisely. To this end, he examined all available sources, asking which information about Nazi crimes was available to which circles at the time and which could get around among the German population:

- Secret situation and mood reports from the Gestapo and security services

- Minutes of the daily conferences of the Goebbels Ministry from 1941/42

- regional and national press reports

- Diaries and letters from contemporaries, including field post from soldiers at the front

- Newly accessible, previously unconsidered files also from the Soviet Union, including as yet unpublished minutes of the "Ministerial Conference" held every two weeks in the Reich Propaganda Ministry and kept by the State Military Archives in Moscow.

The more than five-hour documentary film Der Judenmord - Germans and Austrians report by the Belgian journalist and author Michel Alexandre from 1998 provides insights into the mostly involuntary knowledge of people not directly involved in the Holocaust, but also of individual Nazi perpetrators and victims.

For the last few years, Holocaust research has concentrated on specific local and regional processes in the deportation of Jews from German cities: on the one hand, to clarify the individual fates of the victims as much as possible, and on the other, to determine more precisely the reactions and participation of non-Jews at the time. The Center for Research on Antisemitism at the TU Berlin has also been devoting itself more and more to brightening up the population for a number of years: Bernward Dörner is leading a research project on the subject of The Murder of European Jews and German Society. Knowledge and attitude of the Germans 1941 to 1945.

In regular surveys conducted by the Allensbach opinion research institute in the 1950s and 1960s, between 25 and 40 percent of the Germans questioned stated that they knew very well about the mass murders of Jews in the conquered areas of Eastern Europe . From this, Karl-Heinz Reuband concluded that knowledge of the Holocaust was estimated at up to 35 million of the total population. Eric A. Johnson estimates the percentage based on the same sources at 50% (extrapolated 40 million). However, Frank Bajohr warned against the "deceptive statistical sham accuracy" of such information, which says nothing about the nature of this knowledge, its evaluation and its classification. Together with Dieter Pohl, he comes to the conclusion that the Holocaust was an "open secret" for the Germans: Anyone who wanted to know what happened to the Jews could have known it, from eyewitness reports, from enemy broadcasters and sometimes very much explicit publications by the Nazi regime itself. However, there was a clear lack of curiosity. From 1943 onwards, in connection with the bombing war and the advance of the Red Army, there was widespread fear of punishment in the population and a downright expectation of retaliation, which requires a guilty conscience and thus knowledge of the Holocaust. Guilt projections soon began to appear, such as the rumor spread in 1941 that German-Americans in the USA would have to wear a swastika on their clothing in the future , analogous to the Jewish star .

The fact that research into the topic began so late is explained, like the relatively abstract culture of remembrance, detached from the fate of victims, from persistent repression ( Karola Fings ) or from the research logic (Dieter Pohl): only after the causes and course of the Nazi crimes had largely been clarified , historians could have asked the question of the attitude of the civilian population sensibly.

Investigations by Bernward Dörner from 2007 indicate that despite a lack of detailed knowledge of the exact organizational and technical process, by the summer of 1943 at the latest, the vast majority of Germans expected that all Jews living under Nazi rule should be killed.

Development and function of the attitude of the population

The more recent historical studies examine the mutual influence of regime and population and the different long-term and short-term interests of the Germans, which explain their attitude towards the persecution of Jews. According to the historian Karola Fings , who is involved in such research for the Cologne region , the main historical question is not what the Germans knew about the Nazi crimes, but what they could have known if they had wanted to know .

Longerich first examined the development of anti-Semitic propaganda and the population's reactions to it for each phase of Nazi rule. With this scientific method he came to the threefold result:

- The Nazi regime wanted to hold the population jointly responsible for the crimes by means of a mixture of silence and the announcement of extermination and reacted flexibly to the changing mood of the population in order to steer them.

- Information about the extermination of the Jews was much more widespread among the Germans than previously assumed: Not the majority, but a considerable proportion of the population and not just a small minority , limited to a certain region, occupation or social milieu , despite the Knowing the secrecy of the exact details of the Holocaust and being able to realistically assess its extent and shape.

- Most Germans would not have implemented this knowledge in actions for the Jews and against their persecution; Although the Nazi crimes were not wanted, they submitted to state propaganda.

Anti-Semitic campaigns by the regime met with increasing skepticism, incomprehension and criticism during the course of the war, but without even triggering any public opposition to the persecution of the Jews. The prevailing indifference and passivity would have served to evade any personal responsibility for war, war crimes and the consequences of war through ostentatious ignorance. This then resulted in the widespread distancing from one's own knowledge towards the winners.

Unlike Longerich, Armin Pfahl-Traughber suspects that the lack of active participation of many Germans in anti-Semitic Nazi campaigns is not a distance to anti-Semitism, but only an aversion to the violent actions of the National Socialists.

The question of knowledge of the Holocaust was linked to the debate about possible German collective guilt . However, this was also rejected by some representatives of Germany's war opponents. In the Nuremberg Trials, they worked hard to make not only those who carried out the genocide responsible , but also the initiators and planners of the genocide , for the first time after a world war . The internal German collective guilt debate was therefore also partly interpreted as a distraction from one's own, individually attributable responsibility.

See also

Movie

- Mark Hayhurst, directed: 1944: Bombs on Auschwitz? Documentary with game scenes based on historical quotations and interviews with contemporary witnesses. Germany, 2019, first broadcast on January 21, 2020 ( information from the broadcaster , Jan 2020)

literature

- Knowledge of non-Jewish Germans

- Frank Bajohr , Dieter Pohl : The Holocaust as an open secret. The Germans, the Nazi leadership and the Allies. Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-54978-0 .

- David Bankier: Public Opinion in the Hitler State. The 'final solution' and the Germans. Berliner-Wissenschaft, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-87061-478-1 .

- Eckart Conze , Norbert Frei , Peter Hayes, Moshe Zimmermann : The Office and the Past. German diplomats in the Third Reich and in the Federal Republic. Blessing, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-89667-430-2 .

- Bernward Dörner : The Germans and the Holocaust. What nobody wanted to know, but everyone could know. Propylaea, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-549-07315-5 .

- Robert Gellately : Backing Hitler. Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany. Oxford University Press, 2001 (German translation: Looked at and looked away: Hitler and his people. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart / Munich 2002, ISBN 3-421-05582-3 ).

- Walter Kempowski : Did you know about it? German answers. (1979) Berliner Taschenbuchverlag, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-442-72541-0 .

- Otto D. Kulka, Eberhard Jäckel (Ed.): The Jews in the secret reports of the Nazi sentiment 1933–1945. Droste, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-7700-1616-5 .

- Peter Longerich: “We didn't know anything about it!” The Germans and the persecution of the Jews 1933–1945. Siedler, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-88680-843-2 .

- Ahlrich Meyer : Knowledge about Auschwitz. Perpetrators and victims of the 'Final Solution' in Western Europe. Schöning , Paderborn 2010, ISBN 978-3-506-77023-3 .

- Hans Mommsen : What did the Germans know about the genocide of the Jews? In: Walter H. Pehle (Ed.): Der Judenpogrom 1938. From the “Reichskristallnacht” to genocide. 7th edition, Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-596-24386-6 .

- Klaus von Münchhausen: Secret Reich Matter Auschwitz: The Nazi measures to camouflage the genocide of the Eastern European Jews . Hamburg, Univ.-Diss. 2014. E-dissertations: Entrance to the full text (PDF): Document 1 (2,751 KB), Document 2 (40,681 KB)

- Saul Kussiel Padover : Lie Detector . Interrogations in defeated Germany in 1944/45. (English 1946; German 1999) Econ, 2001, ISBN 3-548-75006-0 .

- Karl-Heinz Reuband: Rumors and knowledge of the Holocaust in German society before the end of the war. An inventory based on population surveys. In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Yearbook for anti-Semitism research . Volume 9, Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2000, pp. 196-233.

- Karl-Heinz Reuband: Rumors and knowledge of the Holocaust in German society before the end of the war. An inventory based on population surveys. In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Yearbook for anti-Semitism research . Volume 9, Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2000, pp. 196-233.

- Samuel Salzborn : Collective Innocence: The Defense of the Shoah in German Remembrance. Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin / Leipzig 2020, ISBN 978-3-95565-359-0 .

- Jochanan Shelliem (Ed.): Don't cry, they just go for a swim! Audio Verlag, Dav 2005, ISBN 3-89813-409-1 .

- Jörg Wollenberg (Ed.): “Nobody was there and nobody knew.” The German public and the persecution of the Jews 1933–1945. 2nd edition, Piper, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-492-11066-5 .

- Alfred de Zayas : Genocide as a State Secret: On Knowledge of the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” in the Third Reich. Olzog , Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-95768-083-9 .

- Individual and local experience reports

- Petra Bopp: Strangers in Sight - Photo albums from the Second World War. Christof Kerber Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-86678-294-5 .

- Wilfried Köppen: Administrative assistance - Until Celle was without Jews. In: Werner Holtfort, Norbert Kandel, Wilfried Köppen, Ulrich Vultejus: Behind the Facades. Stories from a German city. Steidl, Göttingen 1982, ISBN 3-88243-014-1 , pp. 97-102.

- Herbert and Sibylle Obenaus (eds.): "Writing as it really was ..." Karl Dürkefälden's notes from the years 1933–1945. Torch bearer, Hanover 1985, ISBN 3-7716-2311-1 .

- Harald Welzer, Sabine Moller, Karoline Tschuggnall: Grandpa wasn't a Nazi. National Socialism and the Holocaust in Family Memory. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-596-15515-0 .

- Sabine Würich , Karola Fings , Rolf Sachsse, Martin Stankowski: The memory of places. Emons, 2004, ISBN 3-89705-349-7 .

- Knowledge of Jews

- Andreas Kruse, Eric Schmitt: We felt like Germans. Review of the life and situation of Jewish emigrants and camp inmates. Steinkopff, Darmstadt 2000, ISBN 3-7985-1035-0 .

- Allied knowledge

- Richard Breitman: State Secrets. Nazi crimes - tolerated by the allies. Blessing, 1999, ISBN 3-89667-056-5 .

- Walter Laqueur : What nobody wanted to know. The suppression of news about Hitler's final solution. Ullstein, Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-548-33027-4 (English 1980).

- Michaela Hoenicke Moore: Know Your Enemy. The American Debate on Nazism, 1933-1945. Cambridge UP, 2010, ISBN 978-0-521-82969-4 .

- Switzerland

- Gaston Haas: "If you had known what was going on over in the Reich ...": 1941–1943: What was known in Switzerland about the extermination of the Jews. Helbing & Lichtenhahn, Basel 1994.

Web links

- ORF, June 16, 2006: orf.at We didn't know anything about it! (Review of the book by Peter Longerich)

- The Holocaust as an open secret by Frank Bajohr and Dieter Pohl (various newspaper reviews, December 27, 2006)

- Michael Wildt: Collective review: The Germans and the Holocaust. H-Soz-u-Kult, March 2008

- Did the Germans know about the Holocaust? Saul Friedländer says: “Yes, but they didn't care”. New Germany , January 20, 2007

- The terrible secret . In: Der Spiegel . No. 35 , 1981, pp. 124 ( online ).

Single receipts

- ↑ Jane Caplan, Nikolaus Wachsmann (ed.): Concentration Camps in Nazi Germany: The New Histories. Routledge, 2010, p. 25.

- ^ Heinrich W. Grosse: Probation and failure. The Confessing Church in the Church Struggle. Action Reconciliation for Peace Services e. V., 1991, ISBN 3-89246-024-8 , p. 31 f.

- ↑ Quoted by Volker Ullrich: Five shots on Bismarck. Historical reports 1789–1945. Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-49400-5 , p. 199 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ a b Konrad Löw: Jews undesirable. In: FAZ.net . February 28, 2007, accessed July 2, 2015 .

- ↑ Marcel Reich-Ranicki's speech to the Bundestag on January 27, 2012, on bundestag.de

- ↑ haGalil online: Liberation from the deportation train (accessed on December 31, 2013)

- ↑ Alexandra Kraft: How Irene Weiss experienced the hell of Auschwitz . Photos of prisoners, unsuspecting and quietly waiting in front of the gas chamber; Article on stern.de about the Lüneburg Auschwitz Trial from May 7, 2015

- ↑ Bradley F. Smith, Agnes F. Petersen (eds.): Heinrich Himmler. Secret speeches 1933–1945. Propylaea, Frankfurt 1974, ISBN 3-549-07305-4 , p. 169 ff.

- ↑ Eckart Conze, Norbert Frei, Peter Hayes, Moshe Zimmermann: The office and the past. German diplomats in the Third Reich and in the Federal Republic. Karl Blessing, Munich 2010, p. 15 f.

- ↑ Annegret Schüle: Technology without morality, business without responsibility. In: Irmtrud Wojak and Susanne Meinl (eds.): In the labyrinth of guilt. Frankfurt 2003, ISBN 3-593-37373-4 , pp. 199-229.

- ↑ Christian Semler, Stefan Reinicke: The Jews were the ideal enemy . In: taz , November 10, 2006; Interview with Saul Friedländer .

- ^ Frank Bajohr, Dieter Pohl: The Holocaust as an open secret . Munich 2006, p. 58.

- ↑ General Directorate of the Bavarian State Archives (ed.): Paths to Destruction. The deportation of the Jews from Main Franconia 1941–1943. Munich 2003, ISBN 3-921635-77-2 , p. 106 ff. And photos

- ↑ Ruth Andreas-Friedrich: The shadow man. Berlin location. Diary entries 1938–1948. Frankfurt am Main 2000, p. 98.

- ^ Frank Bajohr, Dieter Pohl: The Holocaust as an open secret. The Germans, the Nazi leadership and the Allies. Beck, Munich 2006, p. 63.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German history of society . Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949 . CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 894.

- ↑ Heinz Boberach: Surveillance and mood reports as sources for the attitude of the German population to the persecution of Jews. In: Ursula Büttner : The Germans and the persecution of the Jews in the Third Reich. Revised new edition, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-596-15896-6 , p. 51.

- ↑ Thomas Mann: German listeners! Fifty-five radio broadcasts to Germany. In: the same: Politische Schriften und Reden, Vol. 3. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1968; Peter Longerich: We didn't know anything about that ... , p. 229 and fn. 115 on p. 410.

- ↑ Guido Knopp: Holocaust, p. 333 ( 2nd leaflet ).

- ↑ Daily Telegraph (GB) June 25, 1942

- ↑ Quoted from Richard Breitman: Staatsgeheimnisse. Goldmann, Munich 2001, p. 126.

- ^ Richard Breitman: State Secrets. Munich 2001, p. 130.

- ^ Richard Breitman: State Secrets. Munich 2001, p. 132ff.

- ^ Richard Breitman: State Secrets. Munich 2001, p. 137.

- ↑ Armin Pfahl-Traughber: Discussion of The Holocaust as an Open Secret . In: DÖW Mitteilungen , 179, December 2006, p. 8, doew.at (PDF; 147 kB)

- ↑ Karski correctly named the three extermination camps, Belzec , Sobibor and Treblinka , which had been in operation up to that point .

- ↑ Guido Knopp: Holocaust. P. 334.

- ^ Inside a Nazi Death Camp, 1944. In: eyewitnesstohistory.com. Retrieved July 2, 2015 .

- ↑ Example: The report by Wehrmacht NCO Wilhelm Cornides from August 31 / September 1, 1942 (based on Peter Longerich: The Murder of European Jews. Munich 1989, p. 212f.)

- ↑ Ernst Klee: 'Nice Times'. The murder of Jews from the perspective of the perpetrators and gawkers. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-10-039304-X , p. 7f.

- ^ Günter Brakelmann: Evangelical Church and the persecution of the Jews, p. 74.

- ↑ Peter Lieb: Crimes of the Wehrmacht - What could Wehrmacht soldiers know about the Nazi crimes behind the front? Diary of a perpetrator gazette.de ( Memento from February 1, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Herbert u. Sibylle Obenaus (Ed.): Writing as it really was ... Karl Dürkefälden's notes from the years 1933–1945 . Hanover 1985.

- ↑ Peter Longerich: We didn't know anything about it ... p. 231f.

- ^ Frank Bajohr, Dieter Pohl: The Holocaust as an open secret. Munich 2006, p. 60f.

- ↑ Sönke Neitzel , Harald Welzer : Soldiers: Protocols from fighting, killing and dying. S. Fischer, 2011, ISBN 978-3-10-089434-2 ; Jan Fleischhauer: Contemporary history: women, children, everything . In: Der Spiegel . No. 14 , 2011 ( online review).

- ^ Page no longer available , search in web archives: Page preview of the front page of the Jewish Chronicle from October 24, 1941 (accessed: August 22, 2011).

- ^ On this, David Cesarani : The Jewish Chronicle and Anglo-Jewry 1841-1991. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 1994, ISBN 0-521-43434-3 , p. 175.

- ^ New York Times, October 26, 1941: Slaying of Jews in Galicia depicted; Thousands Living There and Others Sent From Hungary Reported Massacred . See the abstract of the article on the newspaper's website (accessed August 21, 2011). The entire message is shown in Frank Bajohr , Dieter Pohl: The Holocaust as an open secret. The Germans, the Nazi leadership and the Allies. Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-54978-0 , p. 87. German translation as Doc. 101 in: VEJ Volume 7: Soviet Union with annexed areas. Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-486-58911-5 , pp. 328–329.

- ↑ Hannah Arendt: The hidden tradition. Eight essays. Frankfurt a. M. 1976, p. 33. First published in: Jewish Frontier , January 1945.

- ↑ quoted from Volker Ullrich: The Open Secret - Peter Longerich examines a sensitive chapter in our recent history: What did the Germans know about the Holocaust? On zeit.de from April 20, 2006

- ↑ Article by Die Zeit on April 21, 1995

- ↑ The four million Auschwitz arguments against Auschwitz deniers on h-ref.de

- ^ Bryan Mark Rigg, in: Hitler's Jewish soldiers. Cape. 9

- ↑ quoted from The Germans Remain a Dangerous People - Why they went into politics after the collapse of the 'Third Reich' and what is missing today: Helmut Schmidt remembers . In: FAZ , April 9, 2005, p. 36.

- ↑ Gitta Sereny: Albert Speer: His wrestling with the truth. Munich 2001, ISBN 3-442-15141-4 , p. 484. Stefan Krebs, Werner Tschacher: Speer and Er. And we? German history in broken memory. In: History in Science and Education , H. 3, 58 (2007), pp. 163–173.

- ↑ Bernward Dörner: Review by P. Longerich: We didn't know anything about it! HSozkult, June 14, 2006

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society . Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949 . CH Beck, Munich 2003, p. 894.

- ↑ Place of the incomprehensible . In: Der Spiegel . No. 4 , 2005 ( online ).

- ^ Karl-Heinz Reuband: Rumors and knowledge of the Holocaust in German society before the end of the war. An inventory based on population surveys. In: Jahrbuch für Antisemitismusforschung 9 (2000), pp. 196–233.

- ↑ Eric A. Johnson, Karl-Heinz Reuband: What We Knew. Terror, Mass Murder, and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany. An oral history. Basic Books, New York 2005.

- ^ Frank Bajohr, Dieter Pohl: The Holocaust as an open secret . CH Beck, Munich 2006, pp. 64, 141.

- ↑ Frank Bajohr and Dieter Pohl: The Holocaust as an open secret . CH Beck, Munich 2006, pp. 55-79.

- ^ Bernward Dörner: The Germans and the Holocaust. Berlin 2007, p. 608.

- ↑ Radio House Talks on November 9, 2006 at 8:05 p.m. ( Memento from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) on WDR 5

- ^ Review note . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , December 27, 2006; pearl divers

- ↑ Armin Pfahl-Traughber: Review of We didn't know about that! ( Memento from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) for "Blick nach Rechts"

- ↑ Review: Exhibition Wehrmachtsfotografien 2009/2010 shown in Oldenburg, Munich, Frankfurt am Main and Jena. In: Die Zeit , No. 2010/19.

- ↑ Review ( Memento of November 8, 2017 in the Internet Archive )