NLF and PAVN strategy, organization and structure

This article focuses on the land warfare strategy and tactics used by the Main Force VC and NVA (North Vietnamese Army/People's Army-Vietnam) to defeat their American and South Vietnamese (GVN/ARVN) opponents during the Second Indochina War (better known as the Vietnam War). The stress of this article is a comprehensive overview of how the VC (Main Force)/NVA forces operated, the "how" of the VC/NVA war-fighting method.

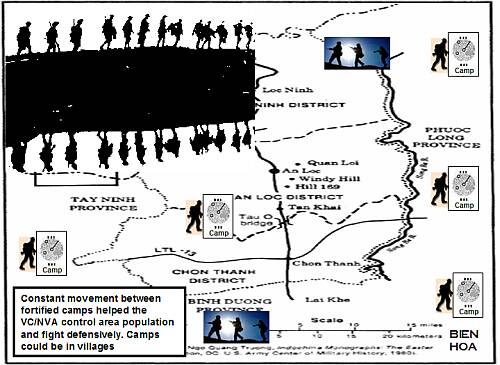

This method involved closely integrated political and military strategy what was called dau tranh. How for example did this strategy compare with the early US "search and destroy" approach? How did they recruit, train, resupply and arm? How did they gain control over so many villages against their South Vietnamese (GVN) opponents? How did they set up their ambushes? How did they attempt to neutralize awesome American firepower? Readers seeking less detailed, more general information are directed to the "See Also" section or articles like Vietnam War. Information more narrowly focused on the American effort can be found in such articles as The United States and the Vietnam War.

The VC in this article identifies the "Main Force" Chu Luc or full-time soldiers of the National Liberation Front, (NLF) an umbrella of groups set up by the rulers of North Vietnam to conduct the insurgency in the south. The term NVA identifies regular troops of the North Vietnamese Army as they were commonly known by their Western opponents. Collectively, both forces were part of PAVN, People's Army of Vietnam, which made up all armed forces of North Vietnam.[1]

Terms used herein, such as "VC", "NVA", "Chicom", "Revolutionary Forces", "regime", etc have no pejorative or partisan meaning but are incorporated here due to their widespread popular usage by both South Vietnamese and American military personnel and civilians, and common usage in standard histories of the Vietnam War.

Overview

During the Second Indochina War (Vietnam War), it is clear that the Main Force VC and NVA were closely linked, sharing a common command, logistical pipeline, and interchange of personnel.[2] Historians like Douglas Pike considered the VC Main Force a branch of North Vietnam's PAVN forces (regular and militia units), using the same methods and organzational structure.[3] Official communist histories echo this view, casting the VC in a more adjunct role and stressing the overall PAVN contribution.[4] While both the VC and NVA had distinctive aspects as separate organizations, in terms of their ultimate mission, leadership and military operations, they were both controlled from the North, ultimately answering to the Lao Dong (communist) Party.[5][6]

Historical development of the VC/NVA

Formation of the VC

The formation of the Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) lies in the communist dominated resistance to the French- the Vietminh.[7] The expulsion of the French had still left a clandestine organization behind in the South, reinforced by thousands of Southerners that had gone North after the communist victory ("regroupees"). This clandestine organization initially focused on political organization and propaganda, and came under heavy pressure by the Diem regime. Diem was an implacable enemy of the Communists and his nationalist credentials were comparatively clean, but he had inherited a very fragile situation. From the beginning he faced the threat of military coups, thrusting criminal gangs, a weak bureaucracy and army, and fierce factional fighting within South Vietnam between not only political factions, but religious groups (Buddhists and Catholics) as well.[8]

Nevertheless Diem caused substantial early damage to the Communist apparatus. Some of his authoritarian methods and nepotism however alienated a variety of groups in South Vietnamese society. Diem's "Denounce Communism" campaign for example, indiscriminately persecuted and alienated numerous civilians (including people who helped the anti-French resistance) who may not have had strong links or sympathies with Communism. Diem's coldness towards Buddhist sensibilities in some areas also aggravated an already shaky situation.[9]

Diem's successful campaign provoked increasing assistance from the Communist North to the clandestine southern formations. As early as 1959, the Central Committee of the Party had issued a resolution to pursue armed struggle. Thousands of regroupees were reinfiltrated south, and a special unit was also setup, the 559th Transport Group, to establish way-stations, trails, and supply caches for the movement of fighting men and material into the zone of conflict.[10] In 1960 the Central Committee formed the National Liberation Front (NLF). Its military wing was officially called the People's Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF) but became more popularly known as the Viet Cong (VC). The NLF/VC took in not just armed guerrillas but served as a broad front for a variety of groups opposed to Diem.

Northern build-up of early southern insurgent forces

The North stiffened the early NLF effort in four ways:[12]

- Sending thousands of northern cadres into the south as leaders and trainers, sometimes aggravating a regional culture clash within revolutionary ranks.

- Standardizing the polyglot VC inventory of fighting arms, including rifles (the AK-47) and machine guns using a common caliber round. Other excellent arms included the RPG-2 and various recoilless rifles.

- Organization of VC units into larger formations, from battalions to regiments, to the first VC division, the famous 9th VC.

- Deployment of NVA regulars to build up logistical networks for later infiltration, (the 559th Transport Group) and insertion of complete regular units such as the 325th Division in remote border areas. [13]

Early effectiveness of the VC

By 1964 the VC, supported by smaller numbers of NVA, were increasingly effective, conducting attacks in regimental strength. The Battle of Binh Gia where the victorious VC held the battlefield for 4 days rather than simply melt away as in earlier times is a vivid example of their confidence and effectiveness. Their operations regularly drubbed Diem's troops, and although Diem's forces controlled a number of urban areas and scattered garrisons, the security situation had become critical.

VC confidence also showed in a number of attacks against American installations and troops, from assaults against places where US soldiers and advisers gathered, to sinking of an American aviation transport ship, the USS Card at a Saigon berth in 1964.[14] Total VC/NVA fighting strength is controversially estimated by the American Military Assistance Command- Vietnam (MACV) at around 180,000 men in 1964. Opposing them during the war's early phases were (on paper by various estimates) over 300,000 ARVN troops and a US troop level that stood at around 16,000 in 1964, This was to increase rapidly in later years.[15]

VC/NVA strategy

The Protracted War conflict model

Prosecution of the war followed the Maoist model, closely integrating political and military efforts into the concept of one struggle, or dau tranh.[16] Dau Tranh was and remains the stated basis of PAVN operations, and was held to spring from the history of Vietnamese resistance and patriotism, the superiority of Marxism-Lennism and the Party, the overwhelming justice of Vietnam's cause, and the support of the world's socialist and progressive forces. War was to be waged on all fronts: diplomatic, ideological, organizational, economic and military. Dau Tranh was divided into military and political spheres:

Political dau tranh: 3 elements

- Dan Van- Action among your people: Total mobilization of propaganda, motivational & organizational measures to manipulate internal masses and fighting units. Example: Intensive indoctrination and total mobilization of all civilian and military personnel in North Vietnam.

- Binh Van- Action among enemy military: Subversion, proselytizing, and propaganda to encourage desertion, defection and lowered morale among enemy troops. Example: contribution to large number of South Vietnamese Army deserters and draft evaders in early years.

- Dich Van- Action among enemy’s people: Total propaganda effort to sow discontent, defeatism, dissent and disloyalty among enemy’s population. Involves creation and/or manipulation of front groups and sympathizers. Example: work among South Vietnamese and US media, activist and academic circles.

Military dau tranh: the 3-phases

The strategy of the communist forces generally followed the protracted Revolutionary Warfare model of Mao in China, as diagramed above. These phases were not static, and elements from one appear in others.[17] Guerrilla warfare for example co-existed alongside conventional operations, and propaganda and terrorism would always be deployed throughout the conflict.

- Preparation, organization and propaganda phase

- Guerrilla warfare, terrorism phase

- General offensive - conventional war phase including big unit and mobile warfare

As part of the final stage, emphasis was placed on the Khoi Nghia, or "General Uprising" of the masses, in conjunction with the liberation forces. This spontaneous uprising of the masses would sweep away the imperialists and their puppets who would already be sorely weakened by earlier guerrilla and mobile warfare. The Communist leadership thus had a clear vision, strategy and method to guide their operations.[18]

South Vietnamese counter-strategy

South Vietnamese (GVN- Government of South Vietnam) counter-strategy was heavily dependent on American aid and personnel. Much emphasis was placed on pacification, and rhetorical claims of "revolutionary" rural development paralleled Communist propaganda. However needed reforms in cleaning up government corruption, land redistribution, attacking the VC infrastructure, and improving the ARVN armies were uneven, or poorly implemented. Unlike Communist forces, the GVN also failed to effectively mobilize a critical mass of its populace behind a nationalist or even an anti-communist narrative on a sustained, large scale basis, although several initiatives were started.

The "Rural Reconstruction" or "Revolutionary Development" Ministry created by Premier Nguyen Cao Ky in 1965 for example, envisioned teams of GVN military and political cadres spreading out across the countryside, rooting out VC infrastructure and agents, providing military security and boosting economic development. Some successes were achieved but the effort foundered due to corruption and inability to provide the promised security. VC attacks killed, wounded or kidnapped over 10,000 cadres, claiming some 500 victims in the first few months of 1967 alone.[19] It is significant however that the aftermath of military defeat of the VC in the 1968 Tet Offensive saw much measurable progress in the South as regards securing its population base.[20]

Improvement of conventional warfare capabilities was also uneven, although elite ARVN units often performed well. A primary GVN weakness was motivation and morale of its general issue forces. ARVN desertion rates in 1966 for example had reached epidemic proportions, and draft dodging was also serious, with some 232,000 evaders failing to report for duty. In 1966, US General Westmoreland forbade the creation of any more ARVN units until the existing ones were brought up to some minimum level of strength. Politicization of the officers corps was also rife, hindering combat training and operations. Relations with the civilian population remained hostile, playing into VC hands. Again however, the 1968 Tet defeat of the VC saw relative progress in conventional forces, although old problems like corruption, leadership and political interference continued to dog them.[21]

These old problems continued into the "Vietnamization" era of the Nixon regime and are well illustrated in the 1971 Laotian Lam Son 719 incursion. [22] Still some writers argue that with continued US material aid, the improved South Vietnamese forces, might have contained a moderate guerrilla-level war for a lengthy period. [23] By 1972, the guerrilla threat had essentially been reduced to low-level proportions and the Southern regime's hand was strengthened. The war however had ceased being primarily a guerrilla conflict and had become conventional, with Hanoi openly bidding for victory during the 1972 Easter attack. ARVN troops simply could not cope in the long term without US assistance and firepower against a ruthless, well organized, and well supplied conventional Northern foe.

With hundreds of thousands dead, and many localized examples of excellent combat performance, important segments of South Vietnamese society put up a strong fight against Northern hegemony. During the 1972 Easter Offensive for example, such resistance highlighted credible performances, not only by elite units like Rangers, Marines or Paratroops, but among elements of regular divisions as well. Strong leadership in the form of commanders like Maj. General Ngo Quang Truong also galvanized and inspired the ARVN effort at places like Hue and An Loc.[24] It is also clear that millions of South Vietnamese opposed the takeover of their society by a totalitarian Communist dictatorship. These included some 900,000 refugees who voted with their feet to move South when Vietnam was partitioned in 1954.[25]

By 1973 however, the Nixon regime faced growing public dissatisfaction, and unremitting pressure by the US Congress, anti-war protesters and much of the US media, to quickly exit Vietnam. The American pull-out left over 150,000 NVA troops in strong tactical positions inside South Vietnam. While aid from the Soviet bloc and China to the North continued unabated, American congressional action cut off the use of US military assets and sharply reduced aid to the South. By 1975, when the final conquest by the NVA/PAVN began, the South Vietnamese were on their own.[26]

American counter-strategy

The US counter-strategy was ineffective in a number of ways against Communist forces. This ineffectiveness was predicted in analyses of weaknesses and contradictions in their enemy's camp (Vo Nguyen Giap, Big Victory, Great Task)[27] An initial policy of gradualism against North Vietnam for example, saw the American President and his Secretary of Defence huddled over maps and charts, planning piecemeal airstrikes on limited targets. These inflicted some localized pain, but had little significant effect on the overall VC/NVA buildup in the south.[28]

Fear of adverse Chinese, Soviet and public reaction also caused US policymakers to put numerous restrictions on American forces until comparatively late in the war. Plans drawn up by the military Joint Chief of Staff, US MACV commander General Westmoreland, and naval chief Admiral Sharp had proposed a strategic offensive, including airborne-amphibous landings north of the DMZ, corps-sized thrusts to liquidate enemy sanctuaries in the DMZ, Laos and Cambodia, a shutdown of incoming war material by mining the vital Haiphong harbor and more bombing of key targets in the Hanoi/Haiphong zone. All of these were rejected by civilian policymakers until very late in the American War. By that time, the focus was on withdrawal of US forces.[29] Some critics have argued that the Joint Chiefs in particular should have been more forceful in standing up to civilian leadership about their misgivings, but whether this would have made any difference is unknown.[30]

Pacification versus 'Search and Destroy' against the VC/NVA

Lively debate still surrounds the "search and destroy" attrition strategy of US General William Westmoreland in the early years of American involvement.[31]

The pacification-first approach. Supporters of the "pacification-first" approach argue that more focus on uprooting the local Communist infrastructure, and cleaning up internal problems would have denied the enemy their key population base, reduced the destructiveness of US operations, strengthened the Southern regime, and yielded better overall results. A massive sweep into thinly populated, remote border jungle, for example, was held to be of less importance than securing key rice-producing villages under pressure by VC operatives, or training ARVN forces to be more effective. They point to the pacification success sometimes achieved by US Marines in their I Corps zone of operations.[32] Such efforts however were marginalized by the main-unit war.

The "big battalion" search and destroy approach. Defenders of "search and destroy" maintain that the Communist shift to Phase 3 warfare required "big battalion" activity to remove the most pressing conventional threats to the Saigon regime. They maintain that since Westmoreland was forbidden from striking with ground forces at Communist concentrations and supply routes in the three countries surrounding the battle zone (Laos, Cambodia and North Vietnam), his attritional strategy within the confines of South Vietnam was the only realistic option against an enemy that had the weak Saigon government on the ropes by 1964. In between are any number of variants on these two themes.[33]

Heavy footprint of US operations on South Vietnam. US forces relied heavily on firepower in their attempt to counter Communist advantages in local concentration, organization, knowledge of the terrain, and the element of surprise in where and when to strike. The VC/NVA had no qualms about provoking US attacks and deliberately using civilians as human shields, sometimes preventing them from leaving an area under attack. [34]. Such methods yielded both practical benefits and cynical propaganda opportunities. Some American tactics caused extensive destruction to the countryside and its inhabitants, including harassment and interdiction fires (H&I), deployment of heavy artillery and bombs in populated areas, the creation of "free-fire" zones, and the generation of refugees. These tactics led opponents of the US war to question their both their legality and morality, and intensified political and diplomatic pressure against American involvement in the conflict.

Some US military sources also questioned their value. A Pentagon Systems Analysis study during the war for example concluded that H&I fires were ineffective and created a negative impression of indiscriminate force by US troops.[35] There were also differences within the US command as well. Leaders such as Marine General V. Krulak favored a more restrained pacification-oriented approach, and his "Spreading Inkblot Theory" questioned the heavy 'search and destroy' philosophy of General W. Westmoreland as not only sometimes counter-productive, but neglectful of controlling key population bases, and developing more effective ARVN forces.[36]

Phases of the war and the conflicting US approaches. Some writers have attempted to reconcile the different schools of thought by linking activity to a particular phase of the conflict. [37] Thus Phase 2 guerrilla assaults might well be met by a pacification focus, while Phase 3 conventional attacks required major counter-force, not police squad or small-patrol activity. The early 1965 stabilization battles such as the Ia Drang, the 1967 border battles, and the 1968 Tet Offensive, are examples of the efficacy of big-unit warfare.[38] The measure of pacification success enjoyed by Westmoreland's successor, General Creighton Abrams, after the Tet Offensive had crippled the Viet Cong can also be seen as an example where pacification was given breathing room to work under cover of the big battalions. Such integration however was never fully achieved by US forces on a sustained basis. By the Abrams era, the US was already phasing down its commitments.[39]

Uneven progress of US pacification effort. The American pacification effort was also ineffective over several critical years, hampered by bureaucratic rivalries between competing agencies, a focus on big-unit operations, and lack of coordination between South Vietnamese civil agencies concerned with pacification and the US military.[40]

The success of pacification efforts were closely linked to security and security improved in the Creighton Abrams era after 1968's Tet battles. By 1972 however, the most pressing problem was not small-scale VC guerrilla activity, but full-scale NVA conventional assaults in divisional strength, backed by tanks and heavy artillery. By late 1972, American troop strength had been reduced to 150,000.

US troop rotation policies also hindered continuity in both pacification and the big-unit war. A one-year tour of duty, for example, left scant time to build the intimate knowledge of an area, its politics, and its people necessary to counter the clandestine Communist infrastructure, and its guerrilla attacks. American advisers and embedded troop elements might just begin to see results on the ground when they were rotated out.[41] The VC/NVA fighter, by contrast, was there for the duration, absent crippling injury or death.

Some writers have questioned whether either pacification or "search and destroy" would have made any difference given dwindling American resolve, the weaknesses noted above, and the Communist strategy of attritional protracted war. [42]

Strategy disputes and shifts in Communist high command

"Southern-firsters" versus "Northern-firsters"

The strategy to govern the war was often a matter of debate within Hanoi's upper echelons.[43] The "northern-firsters" led by Vo Nguyen Giap and Truong Chinh, argued for a more conservative, protracted approach, which allowed the North to consolidate socialism and build its armed forces while the southern revolutionaries assumed primary responsibility for their liberation. Prominent "southern-firsters" led by Le Duan and Nguyen Chi Thanh maintained that the Diem regime was tottering on the ropes and quick victory could be assured by an aggressive push. As noted above, Diem's initially successful suppressive campaign sparked more Northern assistance, and in this early period, the southern-first group appeared to hold sway.

After the fall of Diem, prospects for an easy victory vanished. The introduction of American airpower and troops presented a massive challenge to directors of the communist effort, particularly after the heavy losses taken in open battle with the US at the Ia Drang Valley. Prominent advocates of the "protracted war" camp such as Vo Nguyen Giap, argued for maintaining small-unit guerrilla tactics while holding the Main Forces in reserve, wearing down the Americans attritionally over time. Advocates of the "big clash" camp, such as Nguyen Chi Thanh and Le Duan argued that the VC/NVA were on the verge of victory and that the Americans should be confronted and defeated in conventional style with the Main Force formations.[44]

Thanh's confrontation approach was in the ascendancy for a while as 1967 saw an NVA "border strategy" of drawing US forces to remote jungle areas or zones near border sanctuaries where they could be liquidated in set-piece battles. This emphasis parallels American plans in 1967 to deploy US forces in the more remote areas to assault and neutralize major VC/NVA base areas. Behind them, ARVN and South Vietnamese elements would, presumably, handle pacification duties. US assaults and raids, while often failing to net projected hauls of men and material, did seize the initiative from communist forces in some areas, and dispersed Main Force formations. At the same time, when such Main Forces attempted to stand and fight in the border clashes, they faced the full weight of American firepower and mobility. NVA casualties were heavy in such bloody encounters as Dak To and the First Battle of Khe Sanh.[45]

It should be noted that southerners were prominent among Hanoi's war directors, and included such men as Le Duan, who argued forcefully for more confrontation and the massive introduction of northern men and material into the conflict. The role of southerners was to diminish as the war ended, not only in the northern politiburo but against VC remnants in the south as well. [46]

The Tet Offensive

Tet as a VC defeat

Towards the end of 1967, Hanoi's war directors prepared for a quick knockout blow- the Tong Cong kich, Tong Khai Nghia or "General Uprising" among the Southern masses, known more popularly to Westerners as the Tet Offensive. The major phase of the Tet Offensive would consist of three parts: (a) a series of border assaults and battles to draw US forces out to the margins of South Vietnam, (b) attacks within South Vietnam’s cities by VC forces These infiltrating attacks would bring about a rallying of the masses to the communist cause, and wholesale crumbling and defection of the ARVN forces and Saigon government under the combined pressure of military defeat and propaganda, and (c) large scale set-piece battles to drive the demoralized US imperialists back into coastal enclaves as their South Vietnamese allies wilted. Follow-on attacks in later months would attempt to improve tactical or negotiating positions after the main assault, which began in January 1968.

Tet was a definite change in strategy for the VC which largely had fought smaller-scale mobile and guerrilla warfare since the US arrival. During Tet they would stand and slug it out against the ARVN and Amerians while enjoying the assistance of the aroused masses. The result was a military disaster, not only decimating the VC as an effective fighting force, but exposing much of their clandestine infrastructure. The Khe Sanh battle, while it did succeed in drawing a significant portion of American strength, was not sufficient to prevent or divert a strong US/ARVN response in the cities against the assaulting VC, and involved massive PAVN casualties. The severe losses are noted even in offical Communist sources.[47]

Tet as a strategic VC political and psychological victory

Little documentation from the Communist side shows influencing American public opinion as a primary or even secondary objective of the Tet Offensive.[48] According to North Vietnamese General Tran Do in the aftermath:

- "In all honesty, we didn't achieve our main objective, which was to spur uprisings throughout the south. Still, we inflicted heavy casualties on the Americans and their puppets, and this was a big gain for us. As for making an impact in the United States, it had not been our intention - but it turned out to be a fortunate result."[49]

Attacks on U.S. forces or influencing US elections were not of major importance during Tet. The main thrust was to destroy the GVN regime through demoralizing its armed forces and sparking the hoped for "General Uprising."[50]

Some writers such as Stanley Karnow, question whether there was an immediate American perception of Tet as a defeat however, given the drop in public support for the war prior to Tet, and polls taken during the initial Tet fighting showing a majority of the US public wanted stronger action against Communist forces.[51] Nevertheless, according to Karnow, the Tet fighting seems to have shaken the determination of American political leaders, like US President L. Johnson.[52]

Other writers such as US General Westmoreland, and journalist Peter Braestrup[53] argue that negative press reports contributed to an attitude of defeatism and despair at the very moment American troops were winning against the VC. As such they claim, Tet was major strategic political and psychological triumph for Communist forces in the conflict.[54]

Whatever the merits of these debates or claims, it is clear that the Communist strategy of attritional conflict engendered an increasing war-weariness among their American opponents, whether the pressure was applied over time or more acutely during Tet, or whether guerrilla or conventional warfare was prominent at a particular time. After 1968, the US increasingly sought to withdraw from the conflict, and the future freedom of action by US leaders such as R. Nixon was hindered by domestic anti-war opposition. All of these outcomes flowed from, and were predicted by the strategy of protracted war.[55]

Post-Tet shift back to guerrilla tactics and final shift to conventional warfare

Following Tet, losses compelled communist forces to avoid battle and shift back to small-unit guerilla tactics. The most important of these however, were carried out specialized NVA commando troops, called sappers, alien to South Vietnam, not by the ineffective indigenous Southern VC. Such commando attacks typically involved assaults on fixed bases and camps, and artillery and rocket attacks on fixed military positions or against civilian areas. [56]

During this post-Tet interim, the South Vietnamese regime made relative progress in suppressing Communist infrastructure, a development that concerned the Hanoi government. Still time was on its side. Strong propaganda campaigns coupled with US anti-war protests and legislative action increasingly hamstrung and curtailed the options of US President R. Nixon.[57] As the US pullout accelerated, Northern forces rebuilt and launched the massive 1972 Easter Offensive suffering heavy casualties from US airpower but improving their positions inside South Vietnam. The complete withdrawal of US forces and the curtailment of aid to South Vietnam by the US Congress saw the threat of such air power removed, and final triumph by conventional formations in the Ho Chi Minh Campaign.

Protracted Revolutionary War versus the American/ARVN fighting style

The protracted nature of the Second Indochina War, and its tight integration of political and military struggle ultimately proved more important than specific US or ARVN policies or battles. The American fighting style (emulated by the ARVN unevenly), lay in deploying massive, technologically advanced material resources to bring about a relatively quick decisive struggle. Negating this strength was a strategy of drawn out conflict favoring Communist forces with plenty of time, manpower and ruthless determination. Advanced technology could also be deflected with counter-measures, such as deep tunnel systems or effective propaganda efforts that limited or delayed deployment of technology.[59]

As argued by North Vietnamese General Vo Nguyen Giap, (Vo Nguyen Giap, People's War, People's Army) the Americans, their native allies, and Western powers in general, would not have the staying power for Maoist style protracted conflicts of attrition in the distant Asian country, or in the developing revolutionary situations of the Third World, where led by well organized liberation forces.[60] Although US forces seldom lost a major battle in Vietnam, this analysis largely proved true. It also proved true for ARVN/GVN forces who were eventually vanquished by large scale conventional armies.

NVA Recruitment and Training

Initial recruitment and training. Based on a wide variety of accounts, the performance of some NVA units was excellent, and at times they garnered a grudging respect among those they fought for their discipline, morale and skill. Recruitment was primarily based on the military draft of North Vietnam, and most NVA soldiers served for the duration of the conflict. There were no "rotations" back to the homeland. The typical recruit was a rural youth in his early 20s, with three years of prior cumpulsory training and indoctrination in various militia and construction units. Draftees were mustered at indoctrination centers like Xuan Mia, southwest of Hanoi some months before their actual movement south.

A typical training cycle took 90 to 120 days for the recruit, with instruction on conventional military skills and procedure. Special emphasis was placed on physical conditioning. Heavy political indoctrination was part of the package throughout the cycle, most acutely during a special two-week "study" phase. Organization into three-man cells and kiem thao "criticism and self-criticism" sessions were part of the tight training regimen.[61]

Men selected for infiltration to the South received more intense training- with more political indoctrination, weapons handling, and special emphasis on physical conditioning, particularly marching with heavy packs. Specialized training (heavy weapons, signals, medical, explosives) was given to selected individuals in courses that might last up to a year. Pay and rations for designated infiltrators was more than that given to other troops.

Assessment of the NVA/PAVN fighter. Compared to their VC counterparts most NVA had a higher standard of literacy. While his preparation was not especially impressive by Western standards, the typical NVA soldier proved more than adequate for the task at hand. NVA training was surprisingly conventional, with little special emphasis on jungle warfare. Most of the troops' learning occurred on the job. Service and indoctrination under the communist system prior to army recruitment made the typical NVA fighter a bit older and more seasoned than his American or ARVN opponent. Throughout the conflict, NVA defections and surrenders were extremely low, especially compared to that of the VC, a testimony to their motivation and organization.[62]

VC recruitment and training

As in any guerrilla warfare, control of the populace is the key to the guerrilla's prosperity and survival. To this end, Commmunist forces deployed an elaborate and sophisticated political and propaganda effort.

Importance of the party cadres. Recruitment of VC fighters followed patterns similar to those in Mao's Revolutionary China.[63] Party operatives dominated or influenced most significant activities, and so the initial agents of recruitment were the party cadres, tightly organized into small cells. The cadre, or team of cadres, typically were southern regroupees returning to help the insurgency. Since such persons would have some knowledge of the local area, theirs would not be a "cold call". They would enter a village, and make a careful study of its social, political and economic structure. Cadres usually downplayed communism, stressing local grievances and resentments, and national independence. All was not serious discussion. Musical groups, theater troupes and other forms of entertainment were frequently employed. The personal behavior of cadres was also vital. They were expected to lead austere, dedicated lives, beyond reproach. This would enable villagers to contrast their relatively restrained, non-pecuniary way of life, with the corruption of government representatives or targeted enemies. Female cadres sometimes made effective recruiters, being able to shame and goad young males into committing for the Revolution.[64]

Use of local grievances and individuals. Local grievances and resentments were carefully catalogued by cadres, and detailed information was harvested on each potential supporter or recruit for later use. The cadres would then hit their targets with a variety of methods- friendship, casual political discussions, membership in some community organization, sponsorship of some village festival or event, or activism related to some local grievance or issue. As targets were softened up, the pressure increased. A small nucleus of followers was usually gathered, and these were used to further expand recruitment. The cadres exploited the incompetence, corruption or heavy-handedness of local government officials to stoke the fires. They also seized on perceived injustices by private parties- such as landlords. One vital part of the political effort was to encourage ARVN desertion, draft evasion, lowered morale, and if possible active or tacit support of the Front (NLF/VC). Friends and relatives of soldiers could make effective persuasive appeals while VC operatives who directed the prostelyzing remained hidden in the background.[65]

Creation and manipulation of front groups or infiltration of existing organizations. While the Communist presence in the "united Front" against the US/GVN was no secret, VC operatives took pains to screen the full extent of their influence, and stressed patriotrism, anti-foreign sentiment, local grievances and other issues that could mobilize support. Integral to this process was the creation of "front" groups to mask the true VC agenda.[66] Such groups lent an aura of populist spontaneity and voluntarism while the VC worked them behind the scenes. Such entities could be seemingly innocuous farming cooperatives, or cultural groups, or anything in between. Party members either manipulated these new groups behind the scenes or infiltrated existing ones and gradually took over or influenced them towards the VC line. The goal was to emesh as many people as possible in some group which could then be manipulated. Thus for example a traditional, apolitical rice harvest festival would be eventually twisted into mobilizing demonstrations against a government offical or policy. Members of a farming cooperative might be persuaded into signing a petition against construction of an airfield. Whatever the exact front, issue, or cover used, the goal was control and manipulation of the target population.[67]

The "parallel government" - strengthening the VC grip on the masses. As their web expanded, VC methods became more bold. Hit squads attacked and eliminated selected enemies. Ironically, officials who were TOO efficient or honest might also be liquidated since their conduct might mitigate the grievances and resentments the cadres sought to stoke. Farmers who owned "too much" land might also be fingered. Government facilities, or the private property of those on the target list might also be damaged and sabotaged. Such terror attacks not only eliminated rivals, they served as salutary examples to the villagers as to what could potentially befall them if they opposed the Revolution.[68]

If fully successful, the once sleepy village might be turned into a functioning VC support base.In the early stages of the Vietnam War, American officials "discovered that several thousand supposedly government-controlled 'fortified hamlets' were in fact controlled by Viet Cong guerrillas, who 'often used them for supply and rest havens'."[69] The VC intent was to set up a "parallel" administration, operating clandestinely. Such "revolutionary government" would set and collect taxes, draft soldiers to fight, impress laborers for construction tasks, administer justice, redistribute land, and coordinate local community events and civic improvements. All this activity had one aim- to further the VC/NLF cause, and tighten the Party's grip over the masses.[70]

Intimidation. While a wide variety of front groups and propaganda campaigns were deployed and manipulated by VC political operatives, the VC also tapped effectively into local grievances and nationalist sentiment to attain a measure of genuine popular support in many areas. Parallel with this however, was an unmistakable track of coercion and intimidation.[71] Villagers in a "liberated area" had little choice but to shelter, feed and finance the Revolutionary Forces, and were forced to expand the liberated zone by supplying manpower for constructing and maintaining supply dumps, fortifications, tunnels, and manufacturing facilities.

VC "Armed Propaganda" squads conducted a systematic campaign of assassination and kidnapping to eliminate competitors, intimidate the populace and disrupt or destroy normal social, political and economic life. These two tracks: popular support, and coercion/intimidation, and were to run on together for a good part of the War.[72]

Training of Main Force fighters. Recruits falling into the net were usually taken from the village to another location for political indoctrination and training, sometimes contradicting VC assurances that they would be able to serve near their home areas. Those showing promise were assigned to the Main Force Battalions, which were permanently organized military formations. Other recruits were expected to serve as part-time village helpers or guerrillas. Military training, like that of the NVA was essentially conventional- marching, small unit tactics, basic weapons handling, etc. Illiteracy and lack of education was often a problem in VC ranks, and steps were made to correct this, with focus on the political task at hand. Specialized and advanced training, as in the NVA was given to smaller groups of men. Political indoctrination continued throughout the VC Main Force fighter's training, with nightly "criticism and self-criticism" sessions to eliminate error, and purge incorrect thought.

Assessment of the VC fighter. The quality of VC training and recruitment was more uneven than that of the NVA, and varied based on the war situation. Literacy was lower and defections were several times that of their Northern counterparts. In the context of the protracted insurgency however, and the communist willingness to expend lives, the VC fighting man was more than adequate to fulfill the goals determined by Communist leadership.[73]

Organization of the VC/NVA

Dominant role of Northern based Lao Dong (communist) party

Given the Communist Party's dominance over all spheres of Northern Vietnamese society, including the military struggle, it is impossible to understand VC/NVA organization, strategy and tactics without detailing party involvement. The bulk of the VC/NLF were initially southerners, with some distinctive southern issues and sensibilities. Nevertheless, the VC/NLF was clearly a creature of the Northern Lao Dong Party which manipulated and controlled it -furnishing it with supplies, weaponry and trained cadres, including regular PAVN troops posing as "local" fighters.[74]

Hanoi also organized the Southern Communist party, the Peoples Revolutionary Party (PRP) in 1962, to mobilize communist party membership among southerners, and COSVN, Central Office for Southern Vietnam, which controlled a substantial range of military activity. While a measure of decentralization was necessary to pursue the conflict locally, the PRP, and COVSN, answered ultimately to their Northern handlers.[75] The NVA likewise was controlled by the PAVN High Command, which answered to the Lao Dong, with party committees and representatives supervising and monitoring all echelons. As the war progressed, southern influence weakened, and the northern grip, both military and politically via the Lao Dong Party, was strengthened, a development lamented by some former VC personnel who were forced off the stage by the northerners.[76]

Operating through the PRP personnel, northern cadres and COSVN, and manipulating a variety of front groups, the communist leadership in the North forged a formidable weapon in both the military and propaganda spheres, garnering both internal support in the South, and international support from sympathetic Westerners. Heavily reliant on Chinese and Soviet sponsors for much of their manufactured weapons, the Northern regime, played both these communist giants against each other in the service of its own ends. This ruthless, skillful and tenacious leadership was to achieve final triumph after almost two decades of war.[77]

Complex command structure and geographic commands

The Communist command structure was complex, [78]with a series of interlocking committees and directorates, all controlled by the Central Committee of Hanoi's Lao Dong (Communist) Party. Command of PAVN and some VC forces was shared between the Central Reunification Department and the PAVN High Command, which was nominally under the DRV's Ministry of Defence.

The PAVN High Command supervised all regular NVA forces, but also some Main Force VC formations in the two northernmost Military Regions, and the B-3 Front (Western Highlands). Military Affairs Committees were coordinating groups that liasoned and coordinated activity with the Central Reunification Department. Each front was a military command but was supervised also by regional Party committees set up by Hanoi's Politiburo. The deeper PAVN formations moved into South Vietnam, the more coordination was needed with NLF/VC and regional forces. Hence COVSN was prominent in the southernmost areas, closest to the Cambodian border, where it had its headquarters. COVSN supervised VC forces (Main Force, Regional and Village Guerrilla) in this zone.[79]

There were five geographic/area commands covering South Vietnam. These zones evolved from a simpler two-front division during the early phases of the conflict. The names given below are approximate. More detailed subdivisions existed.[80]

- B-5 "Quang Tri" Front

- B-4 "Tri Thien" Front

- B-3 "Western Highlands" Front

- B-1 Military Region Five Front

- B-2 "Nam-bo" Front

VC structure and Organization

The 5-level administrative structure.[81] Publicly, Viet Cong (VC) forces were part of the liberation peoples movement. In reality they were controlled by COSVN. The VC were organized into 3 Interzone headquarters, that were subdivided into 7 smaller headquarters Zones. The Zones were split into Provinces and further subdivided into Districts. These likewise controlled Village and Hamlet elements. Each level was run by a committee, dominated as always by Communist Party operatives. Each level in theory was subject to the next highest, hence a village commander planning an ambush would have to first apply for clearance from his District bosses, who in turn would refer the matter up the chain of command. This does not imply inflexibility. Local fighters were expected to jump on targets of opportunity, but in general a hierarchy prevailed. The VC were generally grouped into 3 levels.[82]

- VC Main-Force Units. The elite of the VC were the Main Force Units, made up of full-time fighters. These units generally reported to one of the Interzone headquarters or were controlled directly by COSVN. Many of the soldiers were southern-born and had been trained in the north before re-infiltrating back to serve the Revolution. A majority of main-force fighters were party members, wore the pith helmet common to the NVA and could operate in regimental or battalion size strengths.

- The Regional Forces. Regional or territorial units were also full-time soldiers but they generally served within or close to their home provinces. They did not have the degree of literacy of the main-force personnel, and did not have the percentage of Party members present in their ranks. They usually operated in units that seldom exceeded company strength.

- Village guerrillas. Village, hamlet or local guerrillas were part-time fighters and helpers, carrying out minor harassment operations like sniping or mine/booby trap laying, building local fortifications or supply caches, and transporting supplies and equipment. Mostly peasant farmers, these militia style units were under the control of low level NLF or Front leadership.

- Transitions. Although manpower shortages sometimes intervened, a hierarchical promotion system was generally followed between the 3- levels. Promising guerrilla level operatives were moved up to the Regional Forces, and promising Regional Force fighters were promoted to the full-time Main Force units. This ensured that the Main Forces received the best personnel, with some seasoning under their belts.[83]

NVA structure and organization

While NVA formations retained their insignia, signals and logistic lines, supervision followed the same pattern, with Party monitors at every level- from squad to division. Recruitment and training as discussed above was conducted in the North, and replacements were funneled from the North, down the Ho Chi Minh Trail to designated formations. Individual NVA soldiers might be sometimes be assigned as replacement fillers for VC Main Force Battalions. Where distinct NVA formations were kept intact, they remained under the control of the NVA High command, although this was, like other military echelons, controlled in turn by the Northern Lao Dong Party. For a particular operation, NVA units might temporarily be placed under the sway of a COSVN run geographic area.

The NLF "front" framework, gave political cover to these military efforts. Since Party operatives were in place at all levels throughout the entire structure, coordination and control of the vast politico-military effort was enhanced. NVA forces used a typical triangular divisional structure with well articulated sub-units from divisions, through battalions, down to company level.

Organization of VC/NVA units in the field

Both the VC and NVA formations operated under a "system of three" - three cells to a squad, three squads to a platoon, 3 companies to a battalion etc. This could vary depending on operational circumstances. Small-arms dominated the armanent of typical infantry battalions, which deployed the standard infantry companies, logistical support, and heavy weapons sub-units of modern formations. Heavier weapons like 81mm mortars or recoiless rifles and machines guns were at the battalions combat support company. Members of the combat support unit were also responsible for placing mines and booby traps. Command and control was exercised via standard headquarters companies, always supervised by political cadres. Special detachments or platoons included sappers, recon, signals, etc. and were directly responsible to the battalion commander.[84]

Morale and discipline: the 3-man cell and "self-criticism"

- 3-man cells. All soldiers were grouped into 3-man cells. These had practical advantages in mutual support and assistance among soldiers, but when combined with the constant monitoring of the political cadres, they had the benefit of discouraging individual privacy, and potential thoughts of defection. Monitoring by other cell members was inherent in the system. By most accounts given by VC/NVA prisoners or defectors, the cell system served as a powerful instument of cohesion.[85]

- Criticism and self-criticism. Typical of most Maoist communist organizations, "criticism and self-criticism" sessions were frequently conducted to improve discipline, control and cohesion. Such sessions were conducted on a daily basis and after operations. Of key importance was individual confession of faults or errors, and the detection and purging of incorrect thoughts as a basis for behavioral changes. Leaders first critiqued individual soldiers, who in turn were critiqued by their comrades. Admission of faults and weaknesses was then expected from individuals. Lower ranks were not allowed to comment on the actions of higher ranks. Most communist troops seemed to accept the system, especially whene it was conducted in a way that suggested Confucian ideals- that of an elder father or brother correcting wayward youth or siblings.[86]

Role of the Party cadres and officers

At all levels of the structure, the control of the Communist party was constant. Party operatives manipulated civilian front groups and sympathizers, as well as military units. Cadres were assigned to each level of the structure, a "parallel" administration that constantly supervised and watched those tasked with the activities of the Revolution. Commanders of some military units, or leaders of various propaganda and civic fronts might also be Party members, operating openly or undercover.

Cadres were expected to be of exemplary proletarian, moral and political character, faithfully implementing the most recent party line, and monitoring assigned areas for erroneous thought. Class background was important with those from the middle and upper-classes receiving less favorable treatment. Of special importance was the activities of cadres in morale building and in organizing the ubitiquous "criticism and self-criticism" sessions.

The cadre system was a constant in both the VC Main Force and NVA formations down to the company level. Cadres had their own chain of command, parallel with that of the military structure. In any disputes between military officers and the political operatives, the political officers generally had the last word.[87]

VC/NVA equipment and weapons

Overall, the supplies and equipment of communist units while not as lavish or sophisticated as that of their American counterparts were adequate, and their infantry small-arms were more than a match for those of their opponents.[88] Contrary to some popular impressions of simple peasant farmers armed with pitchfork and machetes, the VC/NVA main units were well equipped with excellent modern arms either from Soviet bloc or Chinese sources. In the early years of the insurgency in the South a larger variety of weapons were used, ranging from old WWI bolt-action rifles to Nazi-era weapons, with procurement via a wide range of methods. Such variation and diversity continued throughout the conflict. By 1970 however, the communist inventory was increasingly standardized, even at the village guerrilla level. The following outline shows major weapons categories:[89]

- Small arms- rifles - The standard infantry weapon of the VC/NVA was the Soviet 7.62mm AK47 assault rifle, or its Chicom copy, the Type 56 assault rifle. The Soviet SKS carbine/semi-automatic rifle or its Chicom knockoff was also widely used. Compared to the early American M-16 the rugged AK-47 in particular was more reliable and easier to maintain.

- Machine guns, mortars and interchangeable ammo. Also of key importance to communist units was the interchangeability of the 7.62mm ammunition between the Ak-47 and other types of weapons. The 7.62mm round not only worked well in the SKS carbine but also could be used in the Soviet RPD light machine gun, another standard infantry weapon of the VC/NVA, capable of 150 rounds per minute. Heavier machine guns were sometimes used but often in set piece assaults, or in fixed mode- such as anti-aircraft weapons, due to their weight. Communist units also employed mortars frequently, with the Soviet 82mm and its Chinese variants being the most common. French 60mm mortars also saw some use.

- Rockets and RPGs. The VC/NVA also made extensive use of the excellent Soviet designed anti-tank grenade launcher, the RPG. Originally designed to fight against armor, it was adapted for anti-personnel use to good effect. They also made of the Soviet/Chinese 122mm rocket which was used effectively against populated areas and large installations such as airfields. While inaccurate compared to more sophisticated weapons, the 122mm rocket made an effective terror weapon when deployed against civilian targets. Other rocket types included tube-launched Chicom 107mm and Soviet 140mm variants.

- Anti-aircraft missiles and batteries. The VC/NVA relied heavily on heavy machine guns and standard Soviet designed anti-aircraft batteries for air defence functions. In the latter year of the conflict, field units of the VC/NVA deployed hand-held Soviet designed anti-aircraft missile that presented a significant challenge to US air dominance, particularly helicopters. For strategic aerial defence, the North deployed one of the densest and most sophisticated air-defence systems in the world based on Soviet SAM missiles and radar batteries.

- Grenades, booby traps and mines. The VC/NVA used a wide variety of grenades form explosives inserted into discarded American C-ration cans, to modern Chicom types. Booby traps were the province of guerrilla level forces more than the VC/NVA regulars. The infamous punji sticks soaked in excrement and urine received much press, but they were of negligible effect compared to the massive quantity of anti-personnel and anti-vehicle mines deployed by main communist units. These quantities increased vastly as the North stepped up infiltration into the South. Mines and booby traps applied significant psychological pressure on US/ARVN forces and slowed and disrupted both military operations and civilian life.

- Tanks and artillery. Fighting a mobile guerrilla war much of the time, the VC/NVA could not deploy large quantities of heavy artillery or tanks. Exceptions were the set piece siege battles such as at Khe Sanh or heavy artillery duels against US batteries across the DMZ. It was only after the shift ot conventional warfare int he 1972 Easter Offensive, and the final conventional campaign in 1975 (when US airpower had vacated the field) that tanks and heavy batteries were openly used in significant numbers. When using heavy artillery, the VC/NVA relied on excellent Soviet-supplied heavy 120mm and 130mm guns that outranged American and ARVN opposition.

- Communications VC/NVA formations suffered a shortage of modern radios. Although wire was sometimes run for field telephones in selected operations, they relied heavily on couriers for transmission of messages on the battlefield. Couriers using a "drop box" system were also extensively used for intelligence communications. The whole network was segmented, so that one part did not know the other branches. A courier might leave a message at a specific drop location for another courier (a stranger to him or her). This segmentation helped protect against compromising the network when couriers were captured or killed.

VC/NVA Logistics

VC/NVA logistics were marked by austerity, but sufficient supplies, equipment and material were on hand to furnish final victory. Consumption levels were much less that those of their American/ARVN opponents. It is estimated that a VC/NVA division in the south typically required only 3 tons of supplies per day, compared to 15-20 tons needed by an American one. Soviet bloc and Chinese shipments easily met ordinary communist force requirements.[90] The problem was not the total incoming quantity but moving material up the Ho Chi Minh Trail and other transmission paths, to the point of battle operations. Overall, communist logistacal operations were successful.

Support by the Soviet bloc and China

Communist bloc support was vital for prosecution of the war in the South. North Vietnam had relatively little industrial base. The gap was filled primarily by China and Russia. The Soviet Union was the largest supplier of war aid, furnishing most fuel, munitions, and heavy equipment, including advanced air defence systems. China made significant contributions in medicines, hospital care, use of airfields and training facilities, foodstuffs, and infantry weapons.

Since China bordered Vietnam, it was an immensely important conduit of material on land, although the Soviets also delivered some of its aid by sea. Soviet aid outstripped that of China, averaging over half a billion dollars per year in the later stages of the war, with some $700 million in 1967 alone.[91] China provided an estimated 150 million to 200 million annually, along with such in-kind aid as the deployment of thousands of troops in road and railway construction in the border provinces.[92]

Logistical bases

Communist forces established numerous supply dumps and logistic sites in remote areas of the South. Paralleling these were bases in supposedly neutral countries like Laos and Cambodia, and near the borders of these nations for easy escape. They included command and control bases. All of these were tightly integrated with the way stations, supply caches, and troop shelters of the Ho Ch Minh Trail.

The railway network in the Chinese provinces bordering North Vietnam was of vital importance in importing war material. This was off-limits to American attacks. Communist forces also made extensive use of Vietnam's large netwrok of rivers and waterways, drawing heavily on the Cambodian port of Sihanoukville, which was also off-limits to American attack. Some 80% of the supplies used by the VC/NVA in the southern half of South VIetnam moved through Sihanoukville. [93]

Some port areas of North Vietnam were also vital to the logistical effort, as were ships by socialist nations that fed the continual stream of war material. Attacks on these were also forbidden by American policymakers. Until late in the War, American pilots, hindered by their government's Rules of Engagement, could only watch helplessly as munitions, heavy weapons and advanced components like SAM missile batteries were unloaded at such harbors as Haiphong. [94]

Logistical organization

North-South organization

NVA headquarters in Hanoi was responsible for the coordinating the North to South logistical effort. To this end, it deployed 3 special formations.

- The 603rd Transport Battalion handled sea infiltration and supply movement.

- The 500th Transport Group handled movement of troops and supplies in the North in preparation for the journey south

- The 559th Transport Group was the biggest of the three, numbering an estimated 50,000 troops with 100,000 civilian porters in support. It handled all storage, movement, anti-aircraft defence and fortification on the Ho Chi Minh Trail which snaked through parts of Laos and Cambodia.

The Ho Chi Minh and Sihanouk Trails

(see Wiki article Ho Chi Minh Trail for more details)

Construction of what was to become the famous Ho Chi Minh Trail extended over decades, with elements put in place during the anti-French struggle of the Viet Minh. Known to the North Vietnamese as the Truong Son Strategic Supply Route, the Central Committee of the Lao Dong Party ordered construction of routes for infiltration as early as 1959, under the 559 Transport Group. [95] The Trail was a complex web of roads, tracks, bypasses, waterways, depots, and marshalling areas, some 12,000 miles in total. It snaked through parts of North Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. US policymakers made ground attack against Trail networks in these countries off limits, (until limited operations were permitted late in the War) and communist forces took full advantage of this to move massive quantities of men and material into South Vietnam to attack US and ARVN troops.

The Trail had over 20 major way-stations operated by dedicated logistics units or Binh Trams, responsible for air and land defence, and delivery of supplies and replacements to fighting points in the South. Commo-Liasion units also operated along other trail segments and were tasked with providing food, shelter, medical support and guides to infiltrating troops beween Trail segments.

Most material movement in bulk was not by gangs of sweating coolies, but modern Soviet-suppied trucks. These vehicles rolled on a "relay" basis, moving mostly at night to avoid American airpower, and the trail was plentifully supplied by jungle-like camoflague at all times. Way stations were generally within one day's travel from each other. Trucks arriving at a station were unloaded, and the cargo shifted to new trucks, which carried out the next segment of the journey. Having plenty of both time and manpower, this "relay" method economized on wear and tear upon the valuable trucks, and maximized hiding opportunities from prowling US aircraft. The method also spread out available cargoes over time and space, enabling the entire network to better bear losses from such deadly enemies as the American C-130 Gunship, and such technologies as movement sensors.[96]

The Sihanouk Trail was the American name for the network of roads, waterways and paths cutting through Cambodia that supplied communist forces. Ths network was considered an integral part of the overall supply system incorporating Laos and North Vietnam and centered around the Cambodian port of Kompong Somor Sihanoukville.

- "".. military supplies were sailed directly from North Vietnam on communist-flagged (especially of the Eastern bloc) ships to the Cambodian port of Sihanoukville, where that nation's neutrality guaranteed their delivery. The supplies were unloaded and then transferred to trucks which transported them to the frontier zones that served as PAVN/NLF Base Areas.[8] These Base Areas also served as sanctuaries for PAVN/NLF troops, who simply crossed the border from South Vietnam, rested, reinforced, and refitted for their next campaign in safety." See Wiki article Sihanouk Trail for more detail.

As the war progressed, communist forces expanded and improved the Trail, moving material by truck, installing missile batteries for air defence and laying fuel pipleines. Air interdiction of the Trail hurt communist efforts but failed to stop the logistical buildup on a sustained basis.[97]

Logistical organization inside South Vietnam

Within SVN, the NLF military HQ, COVSN, had responsibility for overall logistical coordination. This changed as the war went on, and the NVA took over more responsibility in-country after the 1968 Tet offensive. This takeover involved settingup new headquarters and replacing fallen VC with NVA regulars. Within the southern logistacal organization, 3 agencies were responsible. Sub-sections of these operated at different levels, from Interzone to village.

- The Finance and Economic grouping was the chief fund raiser, banker and puirchasing agent.

- The Rear Services grouping provided logistical support for military operations, such as digging bunkers or hauling supplies.

- The Forward Supply Council marshalled the money and resources raised by the Finance section, and the services of the rear Group. It controlled civilian labor recuitment, and military recruitment including drafting men into the VC, among other things. Party membership was strongest in the Forward Supply Council.

Overlap and duplication

There was a significant overlap of logistical functions in the communist organization, as the NVA and the VC/NLF civilian agencies worked an area. However overall control was always in the hands of party cadres at all levels, from province down to village. Duplication also produced a wider range of alternative sources for supplies, and made the whole structure more resilient. An American or ARVN sweep for example that wiped out several supply caches did not shut down the whole district. Supply routes using multiple sources, (waterways, black-market transactions, cross-border sanctauries, etc.) could be reopened, and laborers from other regions could be shifted into reconstruction work once the Americans or ARVN left (as they usually did).[98]

Civilian porters

Civilians labor was crucial to VC/NVA success, and was deployed in building fortifications, transporting supplies and equipment, prepositioning material in readiness for an operation, and general construction such as road repair. Labor was recruited primarily by impressment/draft, or as a way to pay off VC taxes, although volunteers motivated by ideology also took part. Twelve to sixteen hours of work per day were expected of laborers. Civlians undertook various pledges as directed by the regime (the "three readies", the "three responsibilities" among others,) as part of a high mobilization of the population for total war in the North and areas controlled by the VC/NVA in the South.[99]

Weapons resupply

VC/NVA weapons had to be moved from shipment points in the North, Cambodia or down the Ho CHi Minh rail. Small, jungle workshops made simpler types of ordnance such as reloading rifle cartridges or grenades. A large amount of small supply depots, widely dispersed to guard against attack, furnished units on the move. Impressed labor groups of civilians also hauled ammo and supplies for the Front.

Food and medical care

Food. The bulk of VC/NVA foodstuffs was procured within South Vietnam via purchase, taxation on peasants in controlled areas, and personal farming by troops in remote areas. Food, along with almost any other item, was also obtained on Saigon's thriving black market. This included large quantities of American food aid to South Vietnam, a phenomenon sometimes observed by US troops that found enemy supply caches.[100]

Medical care. Medical supplies used on the battlefield came from several sources, including Soviet bloc and Chinese shipments and "humanitarian" donations earmarked for civilian use from neutral countries, including Scandinavian nations. Medical care like other aspects of the logistical system was austere, and field hospitals, whether in caves, underground bunkers or jungle huts usually suffered shortages. A one day supply of medicines was usually kept on hand, with the rest hidden off-site until needed. About 7% of a typical VC/NVA division's manpower was made up of medical personnel.[101]

Logistical struggles under US bombing

From 1965 to 1968, North Vietnam was bombed on a scale heavier than the that of the entire Pacific theater during World War II, and absorbed about 20% of US bombing efforts in Southeast Asia. Targeting however was tightly controlled and limited, and while most major industrial centers had been destroyed by 1967, imports from Soviet bloc countries and China furnished most war-making material. The country continued to function for war despite the aerial onslaught.[102]

Facilities and installations were widely dispersed and concealed. Some 2,000 imported generators provided essential power, and oil and gas were shuttled ashore on small craft from Soviet shipsm and stored in thousands of small drums throughout the countryside. Some 500,000 workers were mobilized to repair bomb damage to roads, bridges and other infrastructure, while in the far north some 50,000-100,000 Chinese troops kept border supply routes open. [103]

Total requirements to run North Vietnam's war machine were comparatively small, an estimated 6,000 tons daily in 1967, well below port and rail capacity. Austerity marked Communist logistics. US Intelligence estimates of all Communist non-food requirements in the South averaged about 15 tons per day (or 1.5 ounces per man) in low intensity periods. In 1968 with the Tet Offensive and other major operations, these numbers surged but still weighed in at a modest daily 120 tons. By contrast a single US combat division required about 5 times this amount.[104]

Effectiveness of communist logistics efforts

By 1969 the Trail was a sophisticated logistical web with paved roads, truck parks, maintenance and supply depots, and well organized and defended terminuses and bases, moving thousands of men per month into the battlezone. A fuel pipeline was even in place by 1969, and these were to expand, together with other installations such as missile batteries, as the conflict extended.[105]

A post-war analysis by the BDM Corporation, a think-tank contractor in Vietnam, summarized the efficiency and effectiveness of VC/NVA logistics as follows:

- Subsequently the Communist Vietnamese leadership outlasted America's eight-year combat effort in Southeast Asia, and finally reunited Vietnam by force of arms. A major factor contributing to their success was the remarkable logistical support they created in an integrated network of bases, sanctuaries and lines of communication. Indeed the sanctuaries gave them the trump card that enabled them to fight a protracted war and outlast the United States commitment to the Republic of Vietnam.[106]

VC/NVA use of terror

Murder, kidnapping, torture and general intimidation were a routine part of VC/NVA operations and were calculated to cow the populace, liquidate opponents, erode the morale of ARVN government employees, and boost tax collection and propaganda efforts.[107]

Terror via provoking attacks from US/ARVN forces. Terror results could also be achieved by provoking reaction or retaliation attacks by ARVN or American forces on villagers through sniping, raids, or placing of mines and booby traps in and near villages or hamlets. Such reactions had the benefit of creating potential atrocities that could be used later in propaganda to help mobilize or radicalize elements of the populace.[108] A 1965 Christian Science Monitor article by Japanese journalist Takashi Oka illustrates the method. The VC entered a village and harangued the local populace about supporting the Revolution before passing word to the district capital that they were active in the community. One day later, US planes bombed the village and its Catholic Church. VC operatives emerged after the destruction to tell survivors about the perfidy of the US imperialists.[109] Such methods could sometimes backfire however, with villagers blaming Front forces for the destruction and death brought to their communities.[110]

Atrocities. Several spectacular incidents of terror stand out in VC/NVA operations, although these were not publicized in the Western media to the extent of the American My Lai massacre.[111] During the Tet Offensive, VC hit squads killed more than 2,800 unarmed government officials, schoolteachers and intellectuals in Hue alone.[112] In 1967 the VC used flamethrowers to incinerate 252 civilians, mostly women and children at the village of Dak Son, in Phuc Long Province.[113] In 1970, at the village of Phu Tan, near Da Nang, the NVA killed an estimated 100 civilians as they huddled in bunkers for shelter, by tossing in grenades and satchel charges.[114]

Hit squads and assassinations. During the early years of the war, assassinations and other similar activity was organized via "special activity cells" of the VC. As the conflict extended, efforts were centralized under the VC Security Service estimated to number 25,000 men by 1970.[115] By 1969, nearly 250 civilians were being murdered or kidnapped each week. The total Vietnam War tally of the VC/NVA terror squads stands at 33,000 murders and almost 58,000 kidnappings according to one US Department of Defense estimate, circa 1973.[116]

Official line on terror. Communist forces and spokesmen consistently denied using any terror, and attributed the mass graves at Hue to spontaneous action by various aggrieved peoples of the city.[117] The use of terror however is encouraged in official NLF documents, such as COSVN Resolution Number 9, published in July 1969, which noted:

- "Integral to the political struggle would be the liberal use of terrorism to weaken and destroy local government, strengthen the party apparatus, proselyte among the populace, erode the control and influence of the Government of Vietnam, and weaken the RVNAF."[118]

Intelligence

Communist forces deployed an extensive and sophiscated intelligence apparatus within South Vietnam, extending from the top echelons of the Southern regime, to village level guerrilla helpers informing on ARVN troop movements. Substantial assistance to the southern insurgency was rendered by the North via its Central Research Agency(CRA). This fifth-column built on the anti-French resistance of the Vietminh. The American CIA claimed that by the late 1960s, more than 30,000 enemy agents had infiltrated the GVN's "administrative, police, armed forces and intelligence" operations.[119]

In the South, the NLF's COVSN organization supervised intelligence efforts, deploying a secret police in communist controlled areas, a bodyguard service for VIPs and most importantly, a "People's Intelligence System." Networks of informers were numerous and the system used blackmail, threats and propaganda to secure the cooperation of GVN functionaries, often working through their relatives. One South Vietnamese study of the communist apparatus cited several examples of intelligence gathering for the Front (VC/NVA) forces:[120]

- A bicycle repairman on the road that reported on military traffic

- A farmer counting the number and type of aircraft that landed and took off on the airstrip near his fields

- A peasant woman outside her hut reporting on the size and composition of enemy troops by pre-arranged signal, when they approached.

The infiltration south

Trail movement and hardships

NVA units deemed ready for infiltration were transported from the training centers by train or truck to the coast, at places like Dong Hoi, where they received additional rations. From there they marched south and southwest, towards the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) or Laos, using a variety of routes. Movement was at night to avoid American air attacks. Within the DMZ, there was a rest pause of several days as infiltrators staged for the crossing. Moving in company or battalion sizes, units departed at two-day intervals, with most crossing into Laos along a system of thousands of tracks, roads and paths known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail.[121]

NVA infiltration routes were keyed to the Military regions the infiltrators were assigned to. PAVN units headed for the Tri-Thien region closest to the northern border might infiltrate directly across the DMZ. Those headed further beyond might travel through Laos. The Sihanouk Trail in Cambodia was opened in 1966 to enable PAVN to infiltrate and resupply COVSN in the southernmost zone of South Vietnam.[122]

The Trail covered a wide diversity of rough terrain. Steep mountain slopes had steps gouged into them for climbing. Ravines were bridged with crude bamboo suspension bridges. Ferries shuttled troops across rivers and streams, and crossings were sometimes laid underwater to avoid aerial detection. Large gangs of civilian laborers were drafted to keep the network functioning.

A daily march cycle might begin at 4:00am with a pause around noon, and continuation until dusk- 6:00pm. Generally there was ten minutes of rest per hour, with one day of rest every five. Fifteen to twenty-five kilometeres were covered daily depending on the terrain. Movement was in column, with point and rear elements. Armed liaison agents, who knew only their section of the Trail, led each infiltrating group between way-stations. Way-stations were located deep in the forest, and contained caches of supplies for use by the infiltrators. They were guarded by detachments of the force responsible for infiltration- the 559th Transport Group. Sometimes the troops camped on the Trail itself between stations.

The hardships of the Trail were many. Casualties caused by American airstrikes were low, accounting for only 2% of total losses. More dangerous enemies included malaria, foot infections and a variety of other maladies. Total losses to disease are estimated at around 10 to 20%. Sick soldiers were left to recuperate at various way-stations. Transit time could take months, and sometimes entire units were disrupted and disbanded. [123]

Recruits were generally given an optimistic picture of conditions in the south, with claims that victory was close at hand and that they would be welcomed as liberators by their oppressed Southern brethren. They were often quickly disabused of such notions as they encountered sullen peasants and withering US firepower.[124]

Techniques to deceive or fight US airpower and Special Ops troops