Substance abuse: Difference between revisions

Prashanthns (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 144.134.225.156 (talk) to last version by Thingg |

|||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

An estimated 4.7% of the global population aged 15 to 64, or 185 million people, consume illicit drugs annually.<ref>[http://www.theglobalist.com/DBWeb/StoryId.aspx?StoryId=4033 The Global War on Drugs]</ref><ref>[http://mumbai.usconsulate.gov/jun05.html Combating Drug Abuse]</ref> |

An estimated 4.7% of the global population aged 15 to 64, or 185 million people, consume illicit drugs annually.<ref>[http://www.theglobalist.com/DBWeb/StoryId.aspx?StoryId=4033 The Global War on Drugs]</ref><ref>[http://mumbai.usconsulate.gov/jun05.html Combating Drug Abuse]</ref> |

||

===Public health definitions=== |

|||

I'M HIGH RIGHT NOW!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! |

|||

=D |

|||

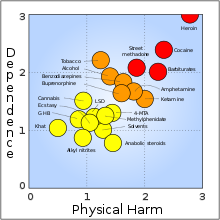

[[Image:Spectrum Diagram.PNG|thumb|Source: [http://www.cfdp.ca/bchoc.pdf A Public Health Approach to Drug Control in Canada, Health Officers Council of British Columbia, 2005]]] |

|||

[[Public health]] practitioners have attempted to look at drug abuse from a broader perspective than the individual, emphasising the role of society, culture and availability. Rather than accepting the loaded terms alcohol or drug "abuse," many public health professionals have adopted phrases such as "alcohol and drug problems" or "harmful/problematic use" of drugs. |

|||

The Health Officers Council of [[British Columbia]] — in their 2005 policy discussion paper, ''[http://www.cfdp.ca/bchoc.pdf A Public Health Approach to Drug Control in Canada]'' — has adopted a public health model of psychoactive substance use that challenges the simplistic black-and-white construction of the binary (or complementary) [[antonym]]s "use" vs. "abuse". This model explicitly recognizes a spectrum of use, ranging from beneficial use to [[addiction|chronic dependence]] (see diagram to the right). |

|||

===Medical definitions=== |

===Medical definitions=== |

||

Revision as of 13:15, 24 April 2008

- This article is an overview of the nontherapeutic use of alcohol and drugs of abuse. For the mental health classification, see substance abuse.

Drug abuse has a wide range of definitions related to taking a psychoactive drug or performance enhancing drug for a non-therapeutic or non-medical effect. All of these definitions imply a negative judgement of the drug use in question (compare with the term responsible drug use for alternative views). Some of the drugs most often associated with this term include alcohol, amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cocaine, methaqualone, and opium alkaloids. Use of these drugs may lead to criminal penalty in addition to possible physical, social, and psychological harm, both strongly depending on local jurisdiction.[2] Other definitions of drug abuse fall into four main categories: public health definitions, mass communication and vernacular usage, medical definitions, and political and criminal justice definitions.[citation needed]

An estimated 4.7% of the global population aged 15 to 64, or 185 million people, consume illicit drugs annually.[3][4]

Public health definitions

Public health practitioners have attempted to look at drug abuse from a broader perspective than the individual, emphasising the role of society, culture and availability. Rather than accepting the loaded terms alcohol or drug "abuse," many public health professionals have adopted phrases such as "alcohol and drug problems" or "harmful/problematic use" of drugs.

The Health Officers Council of British Columbia — in their 2005 policy discussion paper, A Public Health Approach to Drug Control in Canada — has adopted a public health model of psychoactive substance use that challenges the simplistic black-and-white construction of the binary (or complementary) antonyms "use" vs. "abuse". This model explicitly recognizes a spectrum of use, ranging from beneficial use to chronic dependence (see diagram to the right).

Medical definitions

In the modern medical profession, the two most used diagnostic tools in the world, the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and the World Health Organization's International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD), no longer recognise 'drug abuse' as a current medical diagnosis. Instead, they have adopted substance abuse as a blanket term to include drug abuse and other things. However, other definitions differ; they may entail psychological or physical dependence, and may focus on treatment and prevention in terms of the social consequences of substance uses.

Historical medical use of the term

"In the early 1900s, the first edition of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders referred to both alcohol and drug abuse as part of Sociopathic Personality Disturbances, which were thought to be symptoms of deeper psychological disorders or moral weakness [5]. By the third edition, in the 1940s, drug abuse was grouped into 'substance abuse'."[citation needed]

In 1932, the American Psychiatric Association created a definition that used legality, social acceptability, and even cultural familiarity as qualifying factors:

…as a general rule, we reserve the term drug abuse to apply to the illegal, nonmedical use of a limited number of substances, most of them drugs, which have properties of altering the mental state in ways that are considered by social norms and defined by statute to be inappropriate, undesirable, harmful, threatening, or, at minimum, culture-alien."

— Glasscote, R.M., Sussex, J.N., Jaffe, J.H., Ball, J., Brill, L. (1932). The Treatment of Drug Abuse: Programs, Problems, Prospects. Washington, D.C.: Joint Information Service of the American Psychiatric Association and the National Association for Mental Health.

In 1966, the American Medical Association’s Committee on Alcoholism and Addiction defined abuse of stimulants (amphetamines, primarily) in terms of ‘medical supervision’:

…‘use’ refers to the proper place of stimulants in medical practice; ‘misuse’ applies to the physician’s role in initiating a potentially dangerous course of therapy; and ‘abuse’ refers to self-administration of these drugs without medical supervision and particularly in large doses that may lead to psychological dependency, tolerance and abnormal behavior.

Political and criminal justice definitions

Most countries have legislation designed to criminalise some drug use. Usually however the legislative process is self-referential, defining abuse in terms of what is made illegal.[citation needed] The legislation concerns lists of drugs specified by the legislation. These drugs are often called illegal drugs but, generally, what was illegal is their unlicensed production, supply and possession. The drugs are also called controlled drugs or controlled substances.

Potential for harm

Depending on the actual compound, drug use may lead to health problems, social problems, physical dependence, or psychological addiction.

Some drugs have central nervous system (CNS) effects, which produce changes in mood, levels of awareness or perceptions and sensations. Most of these drugs also alter systems other than the CNS. Some of these are often thought of as being abused. Some drugs appear to be more likely to lead to uncontrolled use than others.[6]

Traditionally, new pharmacotherapies are quickly adopted in primary care settings, however, drugs for substance abuse treatment have faced many barriers. Naltrexone, a drug originally marketed under the name "ReVia," and now marketed in intramuscular formulation as "Vivitrol" or in oral formulation as a generic, is a medication approved for the treatment of alcohol dependence. This drug has reached very few patients. This may be due to a number of factors, including resistance by Addiction Medicine specialists and lack of resources. [7]

Legal approaches

- Related articles: Prohibition (drugs), Arguments for and against drug prohibition

Most governments have designed legislation to criminalise certain types of drug use. These drugs are often called "illegal drugs" but generally what is illegal is their unlicensed production, distribution, and possession. These drugs are also called "controlled substances". Even for simple possession, legal punishment can be quite severe (including the death penalty in some countries). Laws vary across countries, and even within them, and have fluctuated widely throughout history.

Attempts by government-sponsored drug control policy to interdict drug supply and eliminate drug abuse have been largely unsuccessful. In spite of the huge efforts by the U.S., drug supply and purity has reached an all time high, with the vast majority of resources spent on interdiction and law enforcement instead of public health.[8] In the United States, the number of nonviolent drug offenders in prison exceeds by 100,000 the total incarcerated population in the EU, despite the fact that the EU has 100 million more citizens.

Despite drug legislation (and some might argue because of it), large, organized criminal drug cartels operate world-wide. Advocates of decriminalization argue that drug prohibition makes drug dealing a lucrative business, leading to much of the associated criminal activity.

See also

- Rat Park

- Doping (sport)

- The Yogurt Connection

- Opium Wars

- Inhalant

- 420 (cannabis culture)

- Spiritual use of cannabis

- Cannabis culture

- Stoner film

- Drug subculture

Notes

- ^ Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C (2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ (2002). Mosby's Medical, Nursing, & Allied Health Dictionary. Sixth Edition. Drug abuse definition, p. 552. Nursing diagnoses, p. 2109. ISBN 0-323-01430-5.

- ^ The Global War on Drugs

- ^ Combating Drug Abuse

- ^ schaeffer

- ^ Jaffe, J.H. (1975). Drug addiction and drug abuse. In L.S. Goodman & A. Gilman (Eds.) The pharmacological basis of therapeutics (5th ed.). New York: MacMillan. pp. 284–324.

- ^ Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences and Education (BCSSE). (2004) New Treatments for Addiction: Behavioral, Ethical, Legal, and Social Questions. The National Academies Press. pp. 7–8, 140–141

- ^ Wood, Evan, et al. (Apr 29, 2003). "Drug supply and drug abuse". Letters. Canadian Medical Association Journal 168:(9). See also: CMAJ, 2003;168(2):165-9.