History of English amateur cricket and Tack (sailing): Difference between pages

m fix |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{redirect|Tacking|the legal concept|Tacking (law)}} |

|||

The '''history of English amateur cricket''' describes the concept and importance of amateur players in English [[cricket]]. The amateur was not merely someone who played cricket in his spare time but a particular type of [[first-class cricket]]er who existed officially until 1962, when the distinction between amateur and professional was abolished and all first-class players became nominally professional.<ref>It may be more accurate to say that the former Gentlemen were in theory amateurs.</ref> Within the scope of this article is the development of cricket in schools, universities and other centres of [[education]], both as a curricular and extracurricular activity. The schools and universities formed the "production line" that created nearly all the first-class amateur players. |

|||

{{Unreferenced|date=December 2007}} |

|||

'''Tack''' is a term used in [[sailing]] that has different meanings in different contexts. |

|||

==Amateurism in cricket== |

|||

The amateur was, by definition, not a professional. In theory, the amateur received expenses for playing cricket, whereas the professional was paid a wage or fee for playing.{{cn}} In fact, many leading amateurs were themselves "well paid" for playing and the greatest "amateur" of them all, [[W G Grace]], made more money out of playing cricket than any genuine professional.{{cn}} |

|||

==Sail== |

|||

The real distinction between amateurs and professionals was social status.{{cn}} Amateurs belonged to the upper and middle classes; professionals invariably came from the working class. The title of the famous [[Gentlemen v Players]] fixture states the difference precisely: the amateurs were all perceived to be "gentlemen", most of whom played primarily for enjoyment; the professionals were simply "players", most of whom took the game very seriously indeed.{{cn}} |

|||

The '''tack''' is the lower corner of the [[sail]]'s leading edge. On a [[sloop]] rigged sailboat, the [[mainsail]] tack is connected to the [[Mast (sailing)|mast]] and the [[Boom (sailing)|boom]] at the [[gooseneck]]. On the same boat, a [[foresail]] tack is clipped to the [[deck (ship)|deck]] and [[forestay]]. |

|||

==Maneuver== |

|||

Originally, all cricketers were amateurs in the literal sense of the word.{{cn}} The sport changed in the wake of the [[Restoration]] in 1660.{{cn}} Gambling interests became involved and the traditional parish teams started to be augmented by star players from elsewhere in the county, or even the country. Some of these star players received fees and bonuses for services rendered to their patrons and it was from this development that the professional player evolved.{{cn}} |

|||

[[Image:Tacking.svg|frame|Tacking]] |

|||

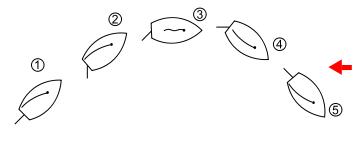

A ''tack''' or '''coming about''' is the maneuver by which a sailing boat or [[yacht]] turns its [[bow (ship)|bow]] through the wind so that the wind changes from one side to the other. During a tack, a vessel's tack (position in accordance to the wind) will change. For example, if a vessel is sailing on a starboard tack (the wind is hitting the starboard side) and tacks, they will end up on a port tack now that the bow has crossed through the direction of the wind and the wind is now hitting the port side. *see image. |

|||

This is in distinction to a [[jibe]] (also known as ''wear'' or ''wearing'' during the age of sail), which is turning the stern of the boat through the wind. |

|||

'''Tacking''' is also incorrectly referred to as [[beating]]. |

|||

Consequently, the word ''amateur'' took on a peculiar meaning of its own in cricket terms that was redolent of social status. It was respectable to be an amateur because that meant you were a "gentleman" and not one of the "roughs" who needed the money. But cricket, for all its social distinctions in this respect, has been common ground for both the gentry and the workers since the early 17th century at least. The gentlemen were not entirely comfortable with that situation and many of their non-cricketing relations and associates were appalled by it. But the sporting types among the well-to-do relished the competition and the opportunity to play against the best performers, who tended to be working class professionals. To compensate for their embarrassment, the amateurs invented a status for themselves that was clearly expressed in terms of separate dressing rooms and the use of "Mr" or a more aristocratic title on the scorecard. On a personal level, amateurs would refer to their professional colleagues by surname only, while the professionals were required to called the amateurs "sir".<ref>Similarly, on contemporary scorecards an amateur would appear as, for example, "Mr PBH May"; a professional as "Laker" or "Laker, JC".</ref> |

|||

===Beating=== |

|||

This was not specific to cricket as it was the normal nomenclature used between middle and working class associates during the 19th century.{{cn}} The "Gentlemen and Players" distinction was a reflection of the higher status officers above other ranks in the [[British Army]], or between employers and the workforce in industry. It therefore seemed natural to most English people of all classes to have a similar distinction in sport. The [[Gentlemen v Players]] matches were a highlight of the English cricket season, although the Players could usually put a much stronger side into the field than the Gentlemen.{{cn}} |

|||

It is the general process by which a ship moves on a zig-zag course towards the direction that the wind is coming from. As no sailing vessel can move directly against the wind—while necessity may dictate that it should go into just that direction—beating allows the vessel to advance against the wind direction. Commonly the closest angle a yacht can sail to the wind is around 35 to 45 degrees, this position is known as [[close hauled]]. |

|||

This perception of amateurs as officers and gentlemen, and thereby leaders, meant that any team including an amateur would tend to appoint him as captain, even though some or all of the professional players might be more skilled technically. The idea was applied to [[Test cricket]] from 1888.{{cn}} Some English touring teams to Australia until then had been all-professional, but England did not appoint another professional captain until [[Len Hutton]] in 1952.{{cn}} It should be pointed out that many of the amateur captains (e.g., [[C B Fry]]) were unquestionably worth their place in the side in terms of technical ability.{{cn}} In the 1930s, [[Walter Hammond]] switched from professional to amateur so that he could captain his country.<ref>Gibson, p. 164.</ref> |

|||

This is done by turning as close into the wind as practicable and then, after a time of sailing, reversing tack to gain back the sideways displacement that occurred during the first tack. Depending on how much sideways space there is (from a small navigable channel to a full ocean) tacks may be minutes or even days in between.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} |

|||

The abolition of amateur status in 1962 was partially the result of long-established disillusionment with a hypocrisy that has been termed "shamateurism", whereby some "amateur" players were given a largely nominal job as "club secretary" and there were sometimes allegations that a few were paid surreptitiously, over and above the ''bona fide'' travelling and hotel expenses that they were entitled to claim.{{cn}} The underlying reason was the tide of social change in the wake of the [[Second World War]] with the growth of both a more egalitarian society in general and a demand for dedicated professionalism in sports such as cricket and [[football (soccer)|football]] that became increasingly conscious of their business obligations and the need to generate income through success on the field.{{cn}} |

|||

Historically, sailing vessels were very bad at sailing against the wind, especially square-rigged ships. This has steadily improved, with modern yachts being able to almost—but not quite—move against the wind direction.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} |

|||

==Co-development of amateur and professional cricket to 1800== |

|||

Cricket probably began in England during the medieval period but there is no definite reference to it until the 16th century. The earliest known reference concerns the game being played c.1550 by children on a plot of land at the Royal Grammar School in [[Guildford]], [[Surrey]]. It is generally believed that cricket was originally a children's game as it is not until the beginning of the 17th century that reports can be found of adult participation. |

|||

===Procedure=== |

|||

====Growth of cricket in the schools and universities==== |

|||

There are few 17th century references to cricket being played at or in the vicinity of schools. It would seem that the sport was played by pupils at [[Eton College]] and [[Winchester College]] (i.e., Wykehamists) by the time of the [[Commonwealth]]. There is an apparent reference to the game at [[St Paul's School, London]] about 1665 concerning [[John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough]], who studied there. |

|||

'''Notify your crew''' that you are tacking. (you are doing this so they are aware of the boom switching sides and to watch their heads) |

|||

In his ''Social History of English Cricket'', Derek Birley comments that school cricket was "alive and well during the interregnum" (1649-1660). He speculates that the game "must have been known to every schoolboy in the south-east" of England. However, he doubts that the sport at this time was part of any school's curriculum. Apart from Eton and [[Westminster School]], all schools in the 17th century had local intakes and no class segregation. Therefore, the sons of rich and poor families played together. Legal cases before the Civil War have shown that cricket was played jointly by gentry and workers. |

|||

As a crew, you may hear one of many terms such as: ''Coming about, Helm's a-lee, Hard a-lee, or Lee Ho'' during the process |

|||

In 1706, [[William Goldwin]] (1682-1747) published his ''Musae Juveniles'', which included a Latin poem called ''In Certamen Pilae'' (On a Ball Game). This has 95 lines and is about a rural cricket match. Goldwin himself attended Eton and then graduated to King's College, Cambridge in 1700. It is almost certain that he encountered cricket at both establishments. |

|||

The next step as a skipper, is to '''push the tiller towards the sail''' or away from you (assuming you are facing your sail and the boom is away from you) |

|||

In 1726, [[Horace Walpole]] entered Eton and later wrote that "playing cricket as well as thrashing bargemen was common"! |

|||

You will hear an intense racking/fluffing/banging noise of your sail (This is good) |

|||

The Sackville family which produced the Dukes of Dorset, most notably [[John Frederick Sackville, 3rd Duke of Dorset|the 3rd Duke]], sent its sons to Westminster. The 1st Duke was there at the end of the 17th century. It was surely through playing cricket at school that the game became a Sackville family tradition. |

|||

This means you are facing directly into the wind (essentially your sail is a flag) marking the half way point through your tack. |

|||

When the noise stops, your sail will calm down and begin to form a smooth curve again (this is good) |

|||

The spread of cricket to the northern counties by 1750 was partly due to "its transmission by interested clergy, schoolmasters and others educated at southern boarding schools" <ref>Birley, p.29</ref>. |

|||

This means you have completed your tacking process and now your vessel is on a different tack (port vs. starboard) |

|||

At this point you should still be facing your sail and the boom away from you. This means that you would have had to switch sides in your vessel as the boom switched sides during the tack. Timing, precision and comfort are all factors into form of tacking and are purely dependent on the sailors preference. However, there is a type of tack known as a roll tack which does have a uniform, "right" way of being completed. |

|||

In the middle part of the 18th century, games involving teams of ''alumni'' became popular. These fixtures ranged from a team of Old Etonians playing the Gentlemen of England in 1751 to a game at the new [[Lord's Cricket Ground]] in 1788 which was entitled "Gentlemen Educated At Eton ''versus'' The Rest Of The Schools". |

|||

Before tacking, it is a good practice to have a considerable amount of speed in order to complete the tack. If a vessel hasn't enough speed to complete a tack, the wind may overpower the boat's turn. The loud noise won't go away at this point and in most cases, your vessel will begin to go backwards as it has no power to fight back the wind which may push back your vessel. This event is most commonly known as "getting stuck in irons" |

|||

Westminster School played its games at Tothill Fields, which was where Vincent Square now stands. It is known to have played matches against Eton in 1792 and 1796. |

|||

An ''auto tack'' is a modern term referring to when a sailboat turns its bow through the wind by accident. This usually occurs in one of two circumstances: either when a steady hand is not kept on the tiller or steering wheel, or when a sudden and large wind shift occurs, such as in a narrow river or lake, causing the wind to come from the other side of the sail even though the boat has not changed course. Auto tacks are more likely to occur when a sail boat is [[close hauled]] but may happen on any point of sail. |

|||

Cricket was thriving at the two great universities too. There is a reference to cricket at [[Cambridge University]] in 1710 while [[Samuel Johnson]] recorded that he played cricket at [[Oxford University]] in 1729. In 1760, the Reverend James Woodforde played for "the Winchester against the Eaton (''sic'')" at Oxford. |

|||

''Beating to windward'' refers to the process of beating a course upwind, and generally implies (but does not require) actually coming about. |

|||

Birley recorded that the "sharpest rivalry" in the middle to late 18th century was between old boys of Eton and Westminster, as these were the two oldest public schools. Notable cricketing patrons who attended those schools include the 3rd Duke of Dorset (Winchester), the [[Charles Bennet, 4th Earl of Tankerville|4th Earl of Tankerville]] and the [[George Finch, 9th Earl of Winchilsea|9th Earl of Winchilsea]] (both Eton). |

|||

When used without a modifier, the term "tacking" is always synonymous with "coming about"; however, one can also "tack downwind"; i.e., change tack by jibing rather than coming about. The reason racing sailboats do this is that most modern sailboats (especially larger boats with spinnakers and a variety of staysails) sail substantially faster on a broad reach than running dead before the wind. The extra speed gained by zigzagging downwind more than makes up for the extra distance that must be covered. Cruising boats also often tack downwind when the swells are also coming from dead astern (i.e., there is a "following sea"), because of the more stable motion of the hull. |

|||

Interestingly, their fellow patron [[Sir Horatio Mann, 2nd Baronet|Sir Horatio Mann]] was an [[Charterhouse School|Old Carthusian]], which indicates that cricket was gaining acceptance at many other schools. By 1800, cricket was firmly established in all public and most grammar schools. |

|||

==Position== |

|||

The most important of these "many other schools" was unquestionably [[Harrow School|Harrow]], which would develop a great cricketing tradition during the 19th century and produce numerous quality players. Harrow had formerly been a grammar school but by the end of the 18th century it had become a public school. Cricket was welcomed at Harrow as elsewhere because it was seen as a useful method for keeping the boys occupied and out of mischief, this despite its strong gambling associations. |

|||

[[Image:PrideofBaltimore1.jpg|right|200px|thumb|This vessel is on port tack.]] |

|||

<!-- Unsourced image removed: [[Image:Stephen Taber 2006.jpg|right|200px|thumb|This vessel is on starboard tack.]] --> |

|||

As a noun, '''tack''' describes the position of a sailboat with respect to the wind and is primarily important as relates to the rules of the road that define which boat has right-of-way when two boats converge. Informally a sailboat's "Tack" is defined by the windward side of the boat at any particular moment-- if the port (or left) side is "to windward", the sailboat is said to be on the "port tack". The "windward" side is not always the side where the wind is coming from however; a boat that is "running" with the wind has the wind coming over its stern and a boat that is in the act of tacking passes through a zone where the wind is coming from directly ahead. For the purposes of right of way rules we therefore define a sailboat's windward side, and therefore the "tack" the boat is on, as being the side opposite the boom; or in the case of a sailboat with multiple masts, the side opposite the mainsail boom. In ''most'' cases a sailing vessel on a ''port tack'' must [[International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea#Section II (for vessels in sight of one another)|give way]] to another sailing vessel on ''starboard tack'' by both the rules of the road and racing rules. Exceptions to this rule occur very occasionally, such as when the port tack boat does not have sea-room to tack or manoeuver out of the way. |

|||

====Gambling and patronage==== |

|||

In the great upsurge of sport after the [[Restoration]], cricket flourished because so many people had encountered it as children and, perhaps especially, at school. But what created [[major cricket]] was gambling. There is no evidence of any kind of ''representative'' cricket before the [[English Civil War]], only references to parish or village cricket. These games are believed to have been similar to the village cricket of today in that most if not all players were resident in the village whose team they played for. The Restoration kickstarted the entertainment industry again after the restrictions imposed by the Puritans during the [[Commonwealth]]. Gambling became rife and cricket, along with horse racing and prizefighting, soon attracted the attention of those who were seeking to make wagers. |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

Cricket matches could not be reported by the press until 1697 because of the prohibitive Licensing Act that was at last repealed in 1696, but there is clear evidence of major matches being played from that time and there can be no doubt that these contests had been going on for many years already, albeit with no reports being published. To boost their chances of winning their wagers, some of the biggest investors began to look beyond the nominal parish XI that they were backing and persuaded good players from other parishes to join a team that soon acquired county strength. The incomers would have been paid a fee and this was the beginning of professionalism. It was also the beginning of [[major cricket|major]] and [[first-class cricket|first-class]] cricket in the sense of teams that were representative of a whole county such as [[Kent county cricket teams|Kent]], [[Surrey county cricket teams|Surrey]] or [[Sussex county cricket teams|Sussex]]. |

|||

{{Sailing manoeuvres}} |

|||

The early reports confirm that many of the main patrons took part in the matches themselves.{{cn}} The likes of [[Edward Stead]], the [[Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond|Duke of Richmond]] and [[Sir William Gage, 7th Baronet|Sir William Gage]] all captained the teams they patronised. It was gentlemen like these, and the friends whom they invited to play, who began cricket's amateur tradition. Thus, a Sussex team of the 1720s might be captained by Richmond and include not only additional amateurs like Gage but also professionals like [[Thomas Waymark]]; and this was the pattern of first-class English teams for a period of 300 years from the 1660s to the 1960s.{{cn}} |

|||

[[Category:Sailing manoeuvres]] |

|||

Waymark was employed by the Duke of Richmond as a groom{{cn}} and this became a common arrangement between patron and professional. Later in the 18th century, professionals like [[Edward "Lumpy" Stevens]] and [[John Minshull]] were employed by their patrons as gardeners or gamekeepers.{{cn}} But in the longer term, the professional became an employee of his club and this trend could be observed in the 1770s when [[Hambledon Club|Hambledon]] paid match fees to its players.<ref>''Barclays World of Cricket'', Collins, 1980, ISBN 0 00 216349 7, pp 3-5.</ref> |

|||

[[Category:Sailing vessels and rigging]] |

|||

[[Category:Nautical terms]] |

|||

[[de:Wende (Segeln)]] |

|||

====Lord's and the MCC==== |

|||

[[fr:Virement de bord]] |

|||

A great watershed in cricket history was the opening of the original Lord's Cricket Ground in 1787. Although Lord's quickly became the sport's greatest venue, it was originally intended to be the private preserve of a gentlemen's club. Members of the White Conduit Club in Islington were uncomfortable with easy public access to their venue at White Conduit Fields and wanted somewhere private to play in peace and quiet. As a result, they contracted one of their own professional bowlers, [[Thomas Lord]], to find such a venue. Lord did so, the club moved in and, when Lord was twice obliged to relocate, the club followed him. Soon after moving to Lord's, the club reconstituted itself as the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC). Originally, only a gentleman could become a member but the club from its very beginning employed or contracted professionals. Lord's immediately began to stage major cricket matches and these attracted the crowds that some members had apparently sought to avoid. MCC teams soon adopted the now age-old pattern of "gentlemen" and "players" in the same team. |

|||

[[nl:Wenden (zeilen)]] |

|||

[[no:Gå over stag]] |

|||

''See also'': [[Lord's Cricket Ground]], [[Marylebone Cricket Club]] and [[White Conduit Club]]. |

|||

[[pl:Zwrot przez sztag]] |

|||

[[sv:Stagvändning]] |

|||

==The rise of amateurism from 1805 to 1863== |

|||

====Schools cricket from 1805 to 1863==== |

|||

Eton and Harrow definitely played each other in 1805 and there is evidence suggesting a game in 1804, perhaps sooner. [[Lord Byron]] played for Harrow in 1805 and may even have hired the venue, which was Lord's. The game seems to have been organised by the boys themselves, not by the schools. |

|||

These two schools soon developed a fierce rivalry that has become the schools cricket equivalent of Cambridge v Oxford or Yorkshire v Lancashire. Eton and Harrow did not meet again until 1818 (twice); then in 1822. After that, the fixture has occurred annually except for 1829-1831, 1856 and in wartime. [[James Pycroft]] in ''The Cricket Field'' commented on the betting at the 1825 game. But by 1833 the match had become a social highlight and ''[[The Times]]'' noted "upwards of thirty carriages containing ladies". Also by this time, the main public schools had grouped themselves into an elite circle and all other schools were decidedly viewed as second class by comparison. The elite were Charterhouse, Eton, Harrow, Rugby, Westminster and Winchester. |

|||

Among prominent amateurs of the Napoleonic period, [[EH Budd|E H Budd]] was an Etonian and [[William Ward (cricketer)|William Ward]] was a Wykehamist. Other noted "old boys" were [[Edward Grimston]], [[Charles Harenc]], Charles Wordsworth (all Harrow), J H Kirwan, Herbert Jenner (both Eton) and W Meyrick (Winchester). |

|||

Ward's old school of Winchester was the main challenger to Eton and Harrow. Harrow v Winchester was first played in 1825 and Eton v Winchester in 1826. Winchester won both of those games convincingly. H S Altham records that "there was a great public school festival at Lord's until its demise in 1854" which involved Eton, Harrow and Winchester. Of 234 "blues" awarded by Cambridge and Oxford from 1827 to 1854, 140 went to pupils of these three schools. |

|||

According to Pycroft, Winchester had the best players in the 1820s and 1830s. At Oxford, their former pupils challenged and defeated the rest of the university and they also won a match against the combined universities at Lord's. |

|||

Six Wykehamists played in the inaugural varsity match in 1827 but the main participants in this were Charles Wordsworth of Harrow and Herbert Jenner of Eton. [[Charles Harenc]] of Harrow became the best amateur bowler of the 1830s. Notable Etonians of the time include Harvey Fellows and the fearsome pace bowler F W Marcon. |

|||

The 1820s and 1830s saw the beginning of "[[Muscular Christianity]]" in the public schools. Dr [[Thomas Arnold]] at Rugby is often considered the "founder" of this movement but in terms of cricket it was at Winchester that the best effect was achieved, especially in their athletic approach to fielding. Although this was hyped as something new, there are plenty of references to outstanding athletic fielders in the 18th century such as [[Thomas Waymark]], [[John Small (cricketer)|John Small]], [[Thomas Taylor (cricketer)|Tom Taylor]] and [[William Yalden]]. |

|||

The earliest references to cricket at [[Rugby School]] and Charterhouse date from the 1820s. Other schools that gained mention in the 19th century include [[Addiscombe Military Academy]], [[Cheltenham College]], [[Clifton College]], [[Malvern College]], [[Marlborough College]], [[Merchant Taylors' School, Northwood|Merchant Taylors' School]], [[Repton School]], [[Shrewsbury School]], [[Tonbridge School]], [[Uppingham School]], [[Wellington School, Somerset|Wellington]] and [[Whitgift School]]. |

|||

====Gentlemen v. Players from 1806 to 1863==== |

|||

[[Image:Gents-v-Players-1899.jpg|right|frame|Gentlemen, captained by WG Grace, vs Players, Lords 1899]] |

|||

The fixture that became the definitive expression of a cricketing class divide was first contested in 1806 when the two teams met twice. Even then, the amateurs realised they were at a real disadvantage and so their team in the inaugural match at Lord's included two of the greatest professional players, [[William Beldham]] and [[William Lambert (cricketer)|William Lambert]] as "given men". Lambert made 57 out of 195 and, given the support he received from [[Thomas Assheton Smith II|T A Smith]], who scored 48, his contribution ensured that the Gentlemen won by an innings and 14 runs. The Gentlemen team was actually quite good as it also included the notorious [[Lord Frederick Beauclerk|Beauclerk]], the controversial [[John Willes (cricketer)|John Willes]], [[Edward Bligh]], [[George Leycester]] and [[Arthur Upton]]. |

|||

In the second match, Beldham went back to the Players and only Lambert was a given man. Lambert again had an outstanding game and the Gentlemen won by 82 runs, though it was Beauclerk's first innings score of 58 from only 96 that was decisive. |

|||

The fixture was tried again in 1819 without much success and then, to quote Birley, it "struggled on". One of the least auspicious occasions was in 1821 when the Gentlemen "gave up" after they had scored only 60 and the Players had reached 270-6. Birley states that this was a Coronation Match to celebrate the accession of the much maligned [[George IV of the United Kingdom|George IV]] and that "it was a suitably murky affair"! |

|||

In 1822, the Gentlemen did manage to win on level terms thanks to their triumvirate of great batsmen: Beauclerk, Budd and Ward. Budd scored 69 out of 138 in the first innings; Beauclerk and Ward built an unbeaten partnership in the second to secure the six wicket win; and really the Players were rather let down by their batting. Having good batsmen and ordinary bowlers was to become a Gentlemen tendency. The Players on the other hand were usually strong in bowling and generally good in batting. |

|||

From 1824 to 1837, the fixture was usually an odds match, the Gentlemen having as many as 18 in 1836. In two matches, the Players were handicapped by different stump lengths! In 1835, the Gents had [[Sam Redgate]] as a given man and he caused a stir by clean bowling [[Fuller Pilch]] twice for nought. In 1836, the great [[Alfred Mynn]] played for the Gents for the first time along with [[Alfred Lowth|Alfred "Dandy" Lowth]]. Lowth was another noted speed merchant even though he was still a 17 year old Winchester school boy; his promising career was cut short due to failing eyesight. |

|||

By 1841, the fixture was in disrepute and MCC refused to organise it. It was only through the efforts of [[Charles Taylor (cricketer)|C G Taylor]] and the [[Frederick Ponsonby, 6th Earl of Bessborough|Hon. F Ponsonby]] that the game could take place. They opened a subscription list to avert its collapse. |

|||

====University cricket from 1827 to 1863==== |

|||

The first [[The University Match (cricket)|University Match]] between [[Cambridge University Cricket Club|Cambridge University]] and [[Oxford University Cricket Club|Oxford University]] took place at Lord's on [[4 June]] 1827. The result was a draw. The captains were [[Charles Wordsworth]] (Oxford) and [[Herbert Jenner]] (Cambridge). It became an annual fixture in 1838. |

|||

Cambridge and Oxford were the only English universities until 1828, when the first college at London University was founded. Durham University was the fourth in 1832 and the first "redbrick" was Owens College at Manchester in 1851. |

|||

About the early days of the two university clubs, H S Altham (himself an Oxford "blue") states that OUCC played on "that part of Cowley Common that was called the Magdalen Ground, so-called because it had been appropriated by the Magdalen College Choir School, whose headmaster made it over" (to OUCC). Cowley Common is in fact some distance from the University itself and so the cricketers used to enjoy a "ride out across the fences"! OUCC moved to [[The Parks]], its present venue, in 1881. |

|||

Altham says that CUCC began at a huge public area called [[Parker's Piece]] but then became tenants at [[Fenner's]] in 1846. The club secured the lease of Fenner's in 1873. F P Fenner had been a bowler with the [[Cambridgeshire CCC|Cambridge Town Club]] (CTC) and had acquired his land in 1846, perhaps for the express purpose of leasing it to CUCC. CTC and the subsequent [[Cambridgeshire CCC]] also played on Parker's Piece. |

|||

Playing standards at the two university clubs were ordinary until the 1860s. Altham admits that many CUCC and OUCC players were selected for the Gentlemen but points out that this owed "less to the strength of the universities than to the weakness of amateur cricket as a whole". |

|||

Noted CUCC players of the period include: [[Charles Taylor (cricketer)|C G Taylor]]; R J P Broughton, who was an outstanding cover point; G J Boudier; R T King, an all-rounder who had an outstanding season in 1849; [[Frederick Ponsonby, 6th Earl of Bessborough|Hon. F Ponsonby]]; J McCormick; J Makinson, who played for [[Lancashire CCC]]; G E Cotterill; H M Marshall; A W T Daniel; Hon. C G Lyttelton; E Sayers; J H Kirwan; E W Blore; R Lang. |

|||

Noted OUCC players of the period include: Hon. [[Robert Grimston]]; V C Smith; C Coleridge; R Hankey; C G Lane; A Paine; W Fellows; R A H Mitchell, an outstanding batsman at Oxford who went on to greater things as coach at Eton in the 1870s; A J Lowth; G B Lee; H E Moberley; C F Willis; G E Yonge; C D Marsham. |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[Gentlemen v Players]] |

|||

* [[Amateur and professional cricketers]] |

|||

==References== |

|||

<references/> |

|||

==Citation sources== |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Altham|first=H S|authorlink=Harry Altham |title=A History of Cricket, Volume 1 (to 1914) |year=1962 |publisher=George Allen & Unwin}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Birley|first=Derek|authorlink=Derek Birley |title=A Social History of English Cricket |year=1999 |publisher=Aurum}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Gibson|first=Alan|authorlink=Alan Gibson |title=The Cricket Captains of England |year=1989 |publisher=The Pavilion Library |isbn=1-85145-390-3}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

* [http://www.jl.sl.btinternet.co.uk/stampsite/cricket/main.html From Lads to Lord's; The History of Cricket: 1300 – 1787] |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

* [[Rowland Bowen]], ''Cricket: A History of its Growth and Development'', Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1970 |

|||

* [[James Pycroft]], ''The Cricket Field'', Longman, 1854 |

|||

* [[David Underdown]], ''Start of Play'', Allen Lane, 2000 |

|||

[[Category:English cricket in the 14th to 17th centuries]] |

|||

[[Category:English cricket in the 18th century]] |

|||

[[Category:English cricket in the 19th century]] |

|||

[[Category:English cricket in the 20th century]] |

|||

Revision as of 07:39, 11 October 2008

Tack is a term used in sailing that has different meanings in different contexts.

Sail

The tack is the lower corner of the sail's leading edge. On a sloop rigged sailboat, the mainsail tack is connected to the mast and the boom at the gooseneck. On the same boat, a foresail tack is clipped to the deck and forestay.

Maneuver

A tack' or coming about is the maneuver by which a sailing boat or yacht turns its bow through the wind so that the wind changes from one side to the other. During a tack, a vessel's tack (position in accordance to the wind) will change. For example, if a vessel is sailing on a starboard tack (the wind is hitting the starboard side) and tacks, they will end up on a port tack now that the bow has crossed through the direction of the wind and the wind is now hitting the port side. *see image. This is in distinction to a jibe (also known as wear or wearing during the age of sail), which is turning the stern of the boat through the wind.

Tacking is also incorrectly referred to as beating.

Beating

It is the general process by which a ship moves on a zig-zag course towards the direction that the wind is coming from. As no sailing vessel can move directly against the wind—while necessity may dictate that it should go into just that direction—beating allows the vessel to advance against the wind direction. Commonly the closest angle a yacht can sail to the wind is around 35 to 45 degrees, this position is known as close hauled.

This is done by turning as close into the wind as practicable and then, after a time of sailing, reversing tack to gain back the sideways displacement that occurred during the first tack. Depending on how much sideways space there is (from a small navigable channel to a full ocean) tacks may be minutes or even days in between.[citation needed]

Historically, sailing vessels were very bad at sailing against the wind, especially square-rigged ships. This has steadily improved, with modern yachts being able to almost—but not quite—move against the wind direction.[citation needed]

Procedure

Notify your crew that you are tacking. (you are doing this so they are aware of the boom switching sides and to watch their heads)

As a crew, you may hear one of many terms such as: Coming about, Helm's a-lee, Hard a-lee, or Lee Ho during the process

The next step as a skipper, is to push the tiller towards the sail or away from you (assuming you are facing your sail and the boom is away from you)

You will hear an intense racking/fluffing/banging noise of your sail (This is good) This means you are facing directly into the wind (essentially your sail is a flag) marking the half way point through your tack.

When the noise stops, your sail will calm down and begin to form a smooth curve again (this is good) This means you have completed your tacking process and now your vessel is on a different tack (port vs. starboard)

At this point you should still be facing your sail and the boom away from you. This means that you would have had to switch sides in your vessel as the boom switched sides during the tack. Timing, precision and comfort are all factors into form of tacking and are purely dependent on the sailors preference. However, there is a type of tack known as a roll tack which does have a uniform, "right" way of being completed.

Before tacking, it is a good practice to have a considerable amount of speed in order to complete the tack. If a vessel hasn't enough speed to complete a tack, the wind may overpower the boat's turn. The loud noise won't go away at this point and in most cases, your vessel will begin to go backwards as it has no power to fight back the wind which may push back your vessel. This event is most commonly known as "getting stuck in irons"

An auto tack is a modern term referring to when a sailboat turns its bow through the wind by accident. This usually occurs in one of two circumstances: either when a steady hand is not kept on the tiller or steering wheel, or when a sudden and large wind shift occurs, such as in a narrow river or lake, causing the wind to come from the other side of the sail even though the boat has not changed course. Auto tacks are more likely to occur when a sail boat is close hauled but may happen on any point of sail.

Beating to windward refers to the process of beating a course upwind, and generally implies (but does not require) actually coming about.

When used without a modifier, the term "tacking" is always synonymous with "coming about"; however, one can also "tack downwind"; i.e., change tack by jibing rather than coming about. The reason racing sailboats do this is that most modern sailboats (especially larger boats with spinnakers and a variety of staysails) sail substantially faster on a broad reach than running dead before the wind. The extra speed gained by zigzagging downwind more than makes up for the extra distance that must be covered. Cruising boats also often tack downwind when the swells are also coming from dead astern (i.e., there is a "following sea"), because of the more stable motion of the hull.

Position

As a noun, tack describes the position of a sailboat with respect to the wind and is primarily important as relates to the rules of the road that define which boat has right-of-way when two boats converge. Informally a sailboat's "Tack" is defined by the windward side of the boat at any particular moment-- if the port (or left) side is "to windward", the sailboat is said to be on the "port tack". The "windward" side is not always the side where the wind is coming from however; a boat that is "running" with the wind has the wind coming over its stern and a boat that is in the act of tacking passes through a zone where the wind is coming from directly ahead. For the purposes of right of way rules we therefore define a sailboat's windward side, and therefore the "tack" the boat is on, as being the side opposite the boom; or in the case of a sailboat with multiple masts, the side opposite the mainsail boom. In most cases a sailing vessel on a port tack must give way to another sailing vessel on starboard tack by both the rules of the road and racing rules. Exceptions to this rule occur very occasionally, such as when the port tack boat does not have sea-room to tack or manoeuver out of the way.