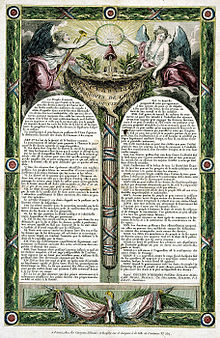

Declaration of human and civil rights from 1793

The declaration of human and civil rights of 1793 ( French Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1793 ) is a basic text which precedes the French constitution of June 24, 1793 . The statement was drawn up by a commission made up of Louis Antoine de Saint-Just and Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles . In contrast to the declaration of human and civil rights of 1789 , not only was the number of human rights increased from 17 to 35, but for the first time equality was put before freedom and the guarantee of property . The constitution and the declaration never officially entered into force.

content

preamble

The French people, convinced that forgetting and disdain for natural human rights are the only causes of calamity in the world, decided to set out in a solemn declaration these sacred and inalienable rights, so that all citizens can constantly pursue the actions of the government with the aim can compare to any social institution and therefore never allow themselves to be oppressed and dishonored by tyranny; so that the people always have the foundations of their freedom and happiness, the authorities the standard of their duties, and the legislature the object of their tasks in mind.

As a result, in the presence of the Most High, she proclaims the following declaration of human and civil rights:

article 1

The goal of society is general happiness.

The government is set up to guarantee that people enjoy their natural and inalienable rights.

Article 2

These rights are equality, freedom, security, property.

Article 3

All human beings are equal by nature and before the law.

Article 4

The law is the free and solemn expression of the general will; it is the same for all, be it that it protects or that it punishes; it can only command what is just and useful to society; it can only forbid what is harmful to it.

Article 5

All citizens are admitted to public office in the same way. In their elections, free peoples have no other reasons for privilege than virtue and talent.

Article 6

Freedom is the power that allows a person to do what does not prejudice the rights of another; it has nature as its basis, justice as its yardstick, and the law as a defense. Its moral limitation lies in the principle: "What you don't want to be done to you, don't do it to anyone else."

Article 7

The right to express one's thoughts and opinions through the press or in any other way, the right to assemble peacefully, and the free exercise of religious services cannot be prohibited.

The need to give expression to these rights presupposes the presence or fresh memory of despotism.

Article 8

Security resides in the protection that society assures each of its members for the preservation of his person, his rights and his property.

Article 9

The law is intended to secure general and personal freedom from oppression by those who rule.

Article 10

Everyone can only be tried, arrested and detained in the cases and in the forms determined by the law. Every citizen summoned or apprehended on the basis of the law must obey immediately; he makes himself punishable by resistance.

Article 11

Any act committed against a person other than the cases and forms specified by law is arbitrary and tyrannical; the person against whom it is to be carried out by force has the right to repel it by force.

Article 12

Those who initiate, promote, sign, carry out or have carried out arbitrary acts are guilty and must be punished.

Article 13

Since every person is to be held innocent as long as he has not been found guilty, if it is deemed necessary to arrest him, any severity that is not necessary to ensure his own person should be seriously by the law to be forbidden.

Article 14

Judgment and punishment may only be given to those who have been heard or legally summoned and only on the basis of a law promulgated before the act was committed. The law that sought to punish offenses committed prior to its creation would be tyranny; to give retroactive force to a law would be a crime.

Article 15

The law is only intended to lay down the punishments that are absolutely and unavoidably necessary; the punishments should be appropriate to the act and useful to society.

Article 16

The right to property is that which allows every citizen to enjoy his goods, his income, the results of his labor and industry, and to dispose of them as he sees fit.

Article 17

No kind of work, acquisition or trade can be denied to the diligence of the citizens.

Article 18

Everyone can dispose of their services and their time; but he cannot sell himself nor be sold; his person is not an alienable property. The law does not recognize servitude; only about the services and the compensation for them can an agreement be made between the person who works and the person who employs him.

Article 19

Without his consent, no one may be deprived of the slightest part of his property, unless it is required by the legally established public necessity, and on the condition of a fair and predetermined compensation.

Article 20

A tax may only be imposed for the general benefit. All citizens have the right to participate in the setting of taxes, to watch over their application and to be accounted for.

Article 21

Public support is a sacred debt. Society owes its unhappy fellow citizens to keep their livelihoods, either by providing them with work or by providing means for their livelihoods for those unable to work.

Article 22

Teaching is a need for everyone. Society should do all it can to promote the advancement of public education and make education accessible to all citizens.

Article 23

The social guarantee consists in the activity of everyone in order to secure the enjoyment and maintenance of his rights for each one: this guarantee is based on the sovereignty of the people.

Article 24

It cannot exist if the limits of public administration are not clearly defined by law and if the responsibility of all civil servants is not guaranteed.

Article 25

Sovereignty rests in the people; it is uniform and indivisible, non-statute-barred and inalienable.

Article 26

No part of the people can exercise the power of the whole people; but any part of the sovereign people that gathers together enjoys the right to express its will with full freedom.

Article 27

Every individual who wants to presume sovereignty is to be immediately sentenced to death by the free men.

Article 28

A people always has the right to revise, improve and change its constitution. A generation cannot subject future generations to its laws.

Article 29

Every citizen has the same right to take part in the legislative process and the appointment of his or her agents or representatives.

Article 30

Public services are by their nature limited in time; they cannot be viewed as awards or rewards, but only as obligations.

Article 31

Offenses by the representatives of the people or their representatives should never go unpunished. Nobody has the right to consider themselves more inviolable than other citizens.

Article 32

The right to submit applications to the public authorities can in no case be prohibited, revoked or restricted.

Article 33

Resistance to oppression is the result of other human rights.

Article 34

It is oppression of the whole of society if even one of its members is oppressed; It is oppression of every single member when the whole of society is oppressed.

Article 35

When the government violates the rights of the people, insurrection is the most sacred of their rights and the most indispensable of their duties for the people and any part of the people.

Web links

- Declaration of human and civil rights from 1793 . In: Verfassungen.eu

Individual evidence

- ↑ Declaration of human and civil rights

- ↑ Axel Herrmann: Struggle for human rights. In: bpb.de. March 11, 2008, accessed December 10, 2018 .