Wage-interest ratio

The term wage-interest ratio (also factor price ratio ) describes in economics the ratio of the price for the production factor labor ( wages ) to the price of the production factor capital ( interest ). The factor price ratio is a value that follows the macroeconomic capital intensity and is used as a guide for the factor endowment of a country. The wage-interest ratio is an important influencing variable for the cost-minimal use of production factors in the production process and therefore has a direct effect on the price of goods . Since the countries are open systems , there is an alignment of the national factor price ratios in the course of foreign trade .

Explanation of terms

The mathematical representation of the relationship between wages (w - wage (English) = wage) and interest (r - rate (English) = interest) is:

Workers are required by companies for production and are rewarded for their performance. The price for work can therefore be tied to the wages of the workers.

There are two different views of the importance of interest in this context.

Interest on capital

In addition to manpower, the company still needs buildings, machines and tools for production. In order to be able to buy these goods , capital must be raised. Interest must again be paid for raising capital. So interest is the price of capital.

Rental costs for capital

In addition to workers, the company still needs production equipment such as buildings, machines and tools for production. These means of production are summarized under the term capital. Sometimes this capital is not bought but rented. The price of capital in this case corresponds to the cost of renting the means of production.

Wage-interest ratio and abundance of factors

The price of a factor of production suggests its abundance. If a factor is cheap, it indicates an abundant factor. On the other hand, it is referred to as a scarce factor if it is expensive. Transferred to the relative factor endowment, a high wage-interest ratio suggests an abundant factor capital. A low wage / interest ratio indicates the abundance of labor.

The abundance of factors in a country is of crucial importance for the use of production factors in the production process (see point 3) and also plays a major role in the direction and extent of foreign trade (see point 4).

Closed economy

A closed economy is understood to be a theoretical economy that does not exchange goods and services with other economies. Autarky prevails in these model considerations .

Historical classification

The model considerations presented below correspond to the neoclassical concept of production theory . The German agricultural and economic scientist Johann Heinrich von Thünen did pioneering work in this area with the second part of his work The Isolated State (1850). But it was only the Swedish economist Johan Gustav Knut Wicksell who succeeded in creating a consistent mathematical formulation of the concepts developed by Thünen in 1893.

One-goods model

Explanation

To produce a good (e.g. food) two production factors are required (labor and capital). By using different combinations of labor and capital ( input ), a certain amount of food ( output ) can be produced.

|

Labor input Capital input |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4th | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20th | 40 | 55 | 65 | 75 |

| 2 | 40 | 60 | 75 | 85 | 90 |

| 3 | 55 | 75 | 90 | 100 | 105 |

| 4th | 65 | 85 | 100 | 110 | 115 |

| 5 | 75 | 90 | 105 | 115 | 120 |

An output quantity of 75 units of food can therefore be achieved with the following input combinations:

- 1 unit of labor and 5 units of capital

- 2 units of labor and 3 units of capital

- 3 units of labor and 2 units of capital

- 5 units of labor and 1 unit of capital

This fact can be represented graphically with the help of isoquants .

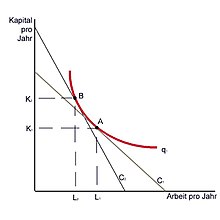

The red curve q 1 (isoquant) represents all input combinations with which the same output is achieved.

Which production variant (combination of labor and capital) a company decides on depends on the prices for labor and capital. If labor becomes more expensive in relation to capital, i.e. the wage rises while the interest rate remains constant (v becomes larger), the company will choose the production variant in which more capital and fewer workers are used. If capital becomes more expensive in relation to labor, i.e. the interest rises with the same wage (v becomes smaller), the company will choose the production variant in which more labor and less capital are used ( factor substitution ). The use of production factors in the production process therefore depends on the respective wage-interest ratio. This fact can also be seen from the graphic. The straight line C 1 ( isocost straight line ) describes the input combinations through which the company incurs the same costs with a certain wage-interest ratio in the production process. The slope of the isocost line corresponds to the negative wage-interest ratio ( ).

The intersection of q 1 and C 1 (point A ) indicates the input combination at which the output q 1 can be produced with minimal costs. Here there is minimal cost production to L 1 units of work and K 1 units of capital. If the price of labor rises, the wage-interest ratio increases. Accordingly, the increase in the isocost line becomes greater; the isocost line becomes steeper (represented by the line C 2 ). There is now a new point of intersection (point B ) with the coordinates ( L 2 , K 2 ), i.e. a new combination of labor and capital is cost-minimal.

Two-goods model

Assumptions

A country produces two different goods (apples and butane). Production takes place through the use of the production factors labor and capital. With any wage-interest ratio, the quotient of capital and labor input in the apple industry (see graph curve AA ) is greater than in the butane industry (see graph curve BB ), which means that more capital is used in the apple industry compared to the butane industry . Apple production is therefore also referred to as capital-intensive . The butane industry produces relatively more labor-intensive than the apple industry because the butane industry uses more labor per unit of capital than the apple industry at identical wages and interest rates.

Explanation

The wages and the interest determine the total production costs of the two goods in a country. An increase in wages while the interest rate remains the same increases production costs for both industries. However, both industries are not affected in the same way. Since the butane industry is more labor intensive, its production costs will rise significantly more than in the apple industry, where work is not so important. An increase in wages relative to interest increases the cost of the more labor-intensive good (butane) in relation to that of the more capital-intensive good (apples).

Effects on goods prices

As a result of competition between producers, the price of every good on the sales market is equal to its production costs. An increase in wages therefore has a greater effect on butane prices than on apple prices. The sales prices for butane will rise faster than the sales prices for apples.

This cause-and-effect relationship can also be viewed in reverse. If consumer preferences change in favor of butane, the demand and consequently the price for butane increases. There is an incentive for suppliers to produce more butane than apples. Since butane is the more labor-intensive commodity, more labor is in turn required. Wages rise and labor becomes more expensive compared to interest. The wage-interest ratio increases.

Open economy

In reality, the countries do not exist as closed economies, but as open systems , that is, they have foreign trade relations with other countries.

Historical classification

The importance of the factor endowment of a country for foreign trade and the consequent change in the wage-interest ratio was first examined by the Swedish economist Eli Filip Heckscher (1879–1952). He developed essential points of the factor endowment theory of international trade, which was published in 1919. The Swedish economist Bertil Ohlin (1899–1979) was considered the successor to Eli Filip Heckscher. He developed and expanded the factor endowment theory in the 1930s.

The factor endowment approach is known as the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem and is considered a modern theory of international trade. The theory has been refined and expanded by many economists in a process that is still ongoing.

Explanation

A 2x2x2 model is used to determine the effect of foreign trade on the wage-interest ratio. The basis for this is the following assumption: Two countries (e.g. Germany and France) produce two goods (e.g. butane and apples) using two production factors (labor and capital). Furthermore, it is defined by definition that the countries differ in their factor allocation. Compared to Germany, France is relatively financially richer. Germany, on the other hand, is relatively more labor-intensive than France. Based on the factor abundance, it is found that the abundant factor is relatively cheap and the scarce factor is relatively expensive. The wage-interest ratio in Germany is consequently smaller than the wage-interest ratio in France.

The country has a relative cost and price advantage and thus a comparative cost advantage for the production of goods, in the production of which the abundant factor is used relatively intensively, since the country can produce this good particularly cheaply. When they enter into foreign trade, the countries expand the production of goods for which they have a comparative cost advantage. Germany will therefore specialize in the butane industry and France in the apple industry. The surpluses not sold in their own country are exported. In Germany, in foreign trade, the demand for the labor factor increases while the demand for the capital factor decreases. In France it is the other way around. The shift in production in Germany makes labor more expensive than capital; the wage-interest ratio increases. At the same time, in France, capital is becoming more expensive than labor; the wage-interest ratio falls. Thus, in the course of entering into foreign trade relations, there is a tendency for the national factor price ratios to converge. See also Heckscher-Ohlin theorem .

The abundant factor, which is relatively cheap before trade, wins because it is rewarded higher after entering into foreign trade. The scarce factor, which is relatively expensive before trade, loses because it is paid lower after entering into foreign trade.

criticism

General

In the 1950s and 1960s a capital controversy developed that made a decisive contribution to the reputation of the neoclassical area of capital theory. This controversy was triggered by the English economist Joan Robinson , who in 1953/1954 referred to the "capital paradox". The capital paradox was recognized by the Italian economist Piero Sraffa through empirical observations. This concerns the relationship between factor input and factor price ratio. It says that it is possible that, for example, an increase in interest rates initially - as expected - leads to a more labor-intensive mode of production, but then - if the interest rate rises further - to a more capital-intensive mode of production again. The factor usage ratio can therefore be reswitched . As a result, there is no clear relationship between the factor input and the factor price relationship. The central postulate of neoclassical production theory that a change in factor prices is unambiguously linked to a change in the factor price ratio was thus refuted. Defenders of the neoclassical, including the American economist Paul Samuelson , were of the opinion that this was merely a pseudo-problem that could arise in individual companies, but was irrelevant from a macroeconomic perspective. It turned out, however, that the capital paradox could not be refuted either on a micro or macroeconomic level.

Only the two production factors labor and capital are recorded in the model. In reality, however, in addition to labor and capital, natural resources (e.g. raw materials) are usually required for the production of goods. In addition, the production factors labor and capital are partly replaced by other production factors such as human capital and natural resources. In order to obtain a comparable result for different countries, the prices for the additional production factors and the substitutes must therefore be included in the facts.

Heckscher-Ohlin theorem

The first and best-known empirical study of the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem was published in a study by the Russian economist Wassily Leontief in 1953. With the USA the most capital-rich country in the world, he expected the statistical data for 1947 to mean that the USA would export capital-intensive goods and import labor-intensive goods. The results of the investigations, however, were the opposite and the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem was thus refuted: US exports were less capital-intensive than imports. This finding is known as the Leontief paradox . This discovery led to numerous considerations as to how this phenomenon could be explained. The different production technologies of the countries in reality (which are regarded as completely identical in the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem) and the special conditions of the post-war period are possible explanations for this.

literature

- Robert S. Pindyck and Daniel L. Rubinfeld: Microeconomics. 6th edition. Pearson, Munich 2005, ISBN 978-3-8273-7164-5 .

- Wilfried J. Ethier: Modern foreign trade theory. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-486-21777-1 .

- Paul R. Krugman and Maurice Obstfeld: International Economy: Theory and Politics of Foreign Trade. 7th edition. Pearson, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8273-7081-7 .

- Gerhard Rübel: Basics of Real Foreign Trade. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-58770-8 .

- Gustav Dieckheuer: International economic relations. 4th edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-486-24854-5 .

supporting documents

- ^ Gerhard Rübel: Fundamentals of Real Foreign Trade. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2008, p. 53.

- ↑ Wilfried J. Ethier: Modern foreign trade theory. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 1991, p. 144.

- ↑ Wilfried J. Ethier: Modern foreign trade theory. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 1991, p. 144.

- ↑ Michael Hohl Stein, Barbara Plow Man Hohlstein, Herbert Sperber, Joachim Sprink: Encyclopedia of Economics. 2nd Edition. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 2003, pp. 392, 592, 593.

- ↑ Robert S. Pindyck and Daniel L. Rubinfeld: Microeconomics. 6th edition. Pearson, Munich 2005, p. 312.

- ^ Gerhard Rübel: Fundamentals of Real Foreign Trade. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2008, p. 53.

- ↑ Fritz Söllner: The history of economic thinking. 2nd Edition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg 2001, p. 69.

- ↑ Robert S. Pindyck and Daniel L. Rubinfeld: Microeconomics. 6th edition. Pearson, Munich 2005, p. 275.

- ↑ based on Robert S. Pindyck and Daniel L. Rubinfeld: Microeconomics. 6th edition. Pearson, Munich 2005, p. 276.

- ↑ Robert S. Pindyck and Daniel L. Rubinfeld: Microeconomics. 6th edition. Pearson, Munich 2005, p. 276.

- ^ Paul R. Krugman and Maurice Obstfeld: International Economy: Theory and Politics of Foreign Trade. 7th edition. Pearson, Munich 2006, p. 107.

- ↑ Robert S. Pindyck and Daniel L. Rubinfeld: Microeconomics. 6th edition. Pearson, Munich 2005, pp. 312, 313.

- ↑ Robert S. Pindyck and Daniel L. Rubinfeld: Microeconomics. 6th edition. Pearson, Munich 2005, p. 314.

- ^ Paul R. Krugman and Maurice Obstfeld: International Economy: Theory and Politics of Foreign Trade. 7th edition. Pearson, Munich 2006, p. 108.

- ↑ Wilfried J. Ethier: Modern foreign trade theory. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 1991, p. 143.

- ↑ Wilfried J. Ethier: Modern foreign trade theory. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 1991, p. 144.

- ^ Paul R. Krugman and Maurice Obstfeld: International Economy: Theory and Politics of Foreign Trade. 7th edition. Pearson, Munich 2006, pp. 108, 109.

- ^ Gerhard Rübel: Fundamentals of Real Foreign Trade. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2008, p. 40.

- ↑ Wilfried J. Ethier: Modern foreign trade theory . 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 1991, p. 138.

- ↑ Wilfried J. Ethier: Modern foreign trade theory . 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 1991, p. 139.

- ↑ Wilfried J. Ethier: Modern foreign trade theory. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 1991, p. 142.

- ↑ Gustav Dieck Heuer: International Economic Relations. 4th edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 1998, p. 64.

- ↑ Gustav Dieck Heuer: International Economic Relations. 4th edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 1998, p. 64.

- ^ Gerhard Rübel: Fundamentals of Real Foreign Trade. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2008, p. 83.

- ↑ Fritz Söllner: The history of economic thinking. 2nd Edition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg 2001, pp. 102-104.

- ↑ Gustav Dieck Heuer: International Economic Relations. 5th edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2001, p. 98.

- ^ Paul R. Krugman and Maurice Obstfeld: International Economy: Theory and Politics of Foreign Trade. 7th edition. Pearson, Munich 2006, p. 123.