Heckscher-Ohlin model

The Heckscher-Ohlin theorem is one of the most influential theories in foreign trade . It comes from two Swedish economists, Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin . Since this theory focuses on the interaction between the proportions in which different factors of production are available in different countries and the proportions in which these are used in the production of different goods, it is also called factor proportion theory. The Heckscher-Ohlin theorem is one of four central theorems derived from the Heckscher-Ohlin model, alongside the Stolper-Samuelson theorem , the factor price equalization theorem and the Rybczynski theorem .

The core idea of the Heckscher-Ohlin model was summarized in the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem . It provides information about the structure of foreign trade, which arises due to different relative factors. Factor endowment is understood to mean all the components that are available for an economy and suitable for production. This means work and capital (classic input factors ). Countries that have a relatively large amount of a factor of production (e.g. capital) will export goods that use this factor intensively (i.e. capital-intensive goods). For example, Germany has a relatively large amount of capital, makes intensive use of this factor and exports a relatively large number of machines and systems. On the other hand, a country like Brazil, which has a large human workforce, specializes in labor-intensive goods like coffee.

Theoretical development of the model

Adam Smith and David Ricardo worked out one of the early world-wide known theories of foreign trade theory . Ricardo extended Smith's approach of absolute cost advantages with his theory of comparative cost advantages . The reasons for advantageous trade led Ricardo to different production functions, i. H. to differences in the global productivity of the factors of production in the different countries. We speak of global factor productivity when we mean the relationship between the input of all production factors (e.g. land and capital) and the output of production. Production functions describe the dependency of the amount of a good produced on the amount of production factors used to produce it . Different production functions mean that the countries have to produce at unequal costs and thus heterogeneous goods prices. Ricardo concluded that after entering into foreign trade, every country specializes in the production of that good whose production has a comparative cost advantage , i.e. H. the absolute cost differences in the manufacture of the individual products diverge. Surpluses of this good are exchanged for those goods whose production it has a comparative cost disadvantage.

While Ricardo's “one-factor model” was based on a single production factor, labor, Heckscher and Ohlin added another production factor to their theory, namely capital .

The model is classically traced back to Bertil Ohlin's 1933 treatise Interregional and International Trade . Nevertheless put Ohlin already in 1924 in his submitted only in the Swedish language and less-received dissertation action Teori ( "trade theory") the basics of the model before. Some elements of the theory were also justified by Eli Heckscher in his article The Effect of Foreign Trade on the Distribution of Income in 1919; Ohlin used this work for his dissertation.

The 2 × 2 × 2 model

“Generally speaking, in any region, abundant factors are relatively cheap and rare factors are relatively expensive. Goods which require much of the former and little of the latter for their production are exported in exchange for goods which require these factors in opposite proportions. So factors that are in abundance are exported indirectly and scarce factors are imported. ”B.Ohlin

According to the Heckscher-Ohlin model, a country will have a comparative advantage in the good the production of which is intensive in relation to the factor that is abundant in that country. Hence, a country that is abundant in capital will have a comparative advantage in capital-intensive industries such as petroleum processing. On the other hand, a country that has ample labor will have a comparative advantage in labor-intensive industries such as textile production.

A good example of the validity of the Heckscher-Ohlin model is world trade in clothing. The production of clothing is a labor-intensive activity: it does not require a lot of physical capital, and it does not require a lot of human capital in the form of well-trained workers. Therefore, one would expect countries where labor is abundant, such as China and Bangladesh, to have a comparative advantage in the textile industry.

Foreign trade comes about when there are differences in relative prices in self-sufficiency ; That is, if domestic and foreign have price advantages for different goods. The simplest version of the factor proportion theory is the so-called 2x2x2 model . In this version there are 2 countries with different factor endowments (domestic and foreign), 2 factors (labor and capital) and 2 goods (correspondingly labor or capital-intensive in production). A distinction is made between factor intensity and factor wealth. The factor intensity affects the two industries, the factor wealth classifies both countries.

Two countries

Although both countries have the same type of production factors (e.g. labor and capital), they have different relative factor endowments. The people in the countries have identical and homothetic preferences . The first property ensures that there are no trade incentives based on preference differences, the second ensures that the relative quantities of the two goods in the optimum consumption are only dependent on the relative prices and not on income. The preferences can be, for example, by a Cobb-Douglas - utility function represent:

- .

Two production factors

There is complete competition in the factor markets and all factors of production are used in equilibrium ( full employment ). Internationally, too, there is perfect competition: Neither labor nor capital have the power to influence prices or factor rates with limited availability. Both countries use identical technologies in production with constant economies of scale . The factor supply is inelastic , that is, independent of the factor prices.

Capital can be split into each technology so that the industrial mix between the types of production can be changed without conversion costs. For example, in agriculture and fishing, the assumption is that farms are sold and boats can be built with them without losing any money.

Two goods

There is a capital-intensive and a labor-intensive good. This means that every good is manufactured using a different technology. So both countries have the same two different production technologies. Goods have the same prices everywhere. Each good in itself is homogeneous, i.e. always of consistent quality.

Factor mobility

The factors are completely mobile within the countries between the two sectors ( factor mobility ), while factor migration between the countries is excluded. As with Ricardo's comparative advantage argument, it is assumed that factors can be redistributed at no additional cost. If the two production technologies are agriculture and the fishing industry, then it is assumed that farmers can work as fishermen and vice versa without incurring additional costs.

The international immobility of factors is necessary to explain long-term trade. For example, if capital could be freely invested anywhere, competition (of investments) will balance the amounts of capital worldwide. Mainly, free trade in investments would mean a global investment pool. Movements of the labor factor are also not provided. This would lead to an approximation of the relative quantities of the two factors of production.

The national factor mobility and at the same time international factor mobility are strict assumptions of the model.

Other general assumptions

There are no restrictions on trading by tariffs and no market control (capital is immovable, but repatriation of overseas sales is free). There are no transport costs for trading the goods . If two countries have different currencies, this does not affect the model in any way. Since there are no transaction costs or currency-related losses, goods are offered abroad at the same price as in Germany.

In Ohlin's day this was quite an oversimplification, but economic changes and econometric experience since the 1950s have shown that local prices of goods are related to incomes (although this is less the case for commercial goods).

In spite of the incentive of the comparative advantage in international trade, none of the countries specializes in a single good. The production costs are equal to the long-term prices, which are identical for both countries. This results in a balance in the prices of goods. In a balanced trade, economic spending must not exceed income. However, this restriction will change with the definition of factor wealth. World trade is free from obstacles such as customs duties and exchange controls, as well as free from transport costs. Goods and factor markets are characterized by free and complete competition. Furthermore, the economic agents are price takers and informed about all market events.

Equilibria

Self-sufficiency

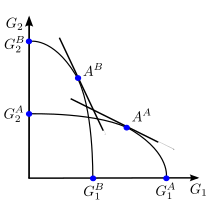

The situation without trade is defined as the reference value (self-sufficiency). Each country will find an optimal combination of minimum costs here, which brings its possibilities ( transformation curve ) into harmony with its goal ( indifference curves ). In the case of self-sufficiency, the country will consume its production itself: that is, in the points , production corresponds to consumption and there is no trade. It has been assumed that the transformation curve is not a linear function; H. the opportunity cost along the curve is not constant.

In the optimum, the opportunity costs correspond to the relative price of good 1.

trade

If there is trade between two countries, each country will produce the relatively factor-intensive good even more (see points ) in order to export this surplus. It can accordingly import more of the other good so that the new equilibrium lies outside the individual transformation curves (see points ). In this model, free trade continues to have advantages for those involved.

Conclusions from the basic model

The Heckscher-Ohlin theorem is an important part of modern foreign trade theory. On the one hand, it serves to explain inter-industrial trade, i.e. H. that part of trade in which a country exports goods from one branch and imports goods from another branch in return. On the other hand, it shows the long-term effects of taking up foreign trade or influencing the corresponding trade flows through economic policy measures on different groups within a country.

Classical theorems in the HO model

Based on the assumptions of the model, important results were formulated as theorems.

- Heckscher-Ohlin theorem : A country exports the good whose production uses the factor relatively intensively, which is relatively abundant in the country, and imports the good whose production uses the factor relatively intensively, which is relatively little available in the country .

- Stolper-Samuelson Theorem (1941): Trade leads to higher reward for the abundant factors.

- Factor price equalization theorem (1948): through trade, factor prices equalize (and goods prices).

- Rybczynski theorem (1955): Factor migration increases the output of the sector that uses this factor intensively.

Further special statements

If certain raw materials occur exclusively in one country, then these countries export the corresponding goods to those countries that demand these products but cannot manufacture them themselves. The model also explains retail in extreme cases that there is only one good.

In the case of identical technology and factor endowments, there can still be trade in the presence of homogeneous goods if the demand relationships differ (different preferences).

Empirical review and criticism

In an empirical review of the factor proportion theory for the USA , Wassily Leontief found in 1953 that, contrary to this prediction, the USA primarily exported labor-intensive goods and imported capital-intensive goods (so-called Leontief paradox ). The Leontief paradox triggered a large number of empirical follow-up studies on the contradiction between empiricism and theory.

Leontief found a solution to this paradox by distinguishing between the different qualities of labor and capital: The USA exported goods that required a well-qualified labor force to produce, while the imported goods required a large but technically not very demanding capital stock. This led to the formulation of the neo-factor proportion theory .

The factor price equalization theorem or Stolper-Samuelson theorem is an extension of the idea . Furthermore, Stuffan B. Linder tried to use the Linder hypothesis to correct the weaknesses of the Heckscher-Ohlin model.

In general, however, empirical studies allow the conclusion that this theorem maps trade between industrialized and developing countries far better than trade between industrialized countries, which usually differ less in terms of their factor prices.

Model extensions

The model has been expanded by many economists since the 1930s. These developments did not change the fundamental role of variable factor ratios in international trade, but it did add various real aspects (e.g. tariff agreements) to the model in hopes of increasing the predictive power of the model or of making it a mathematical means by which macroeconomic problems can be examined.

Important contributions came from Paul A. Samuelson , Roland Jones and Jaroslav Vanek , so that these variants are sometimes referred to as the Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson model or the Heckscher-Ohlin-Vanek model.

The version 2x2x2 corresponds to the simplest modeling in the HO model. A model variant with several factors and several goods was developed by Harry Bowen , Edward Leamer and Leo Sveikauskas (1987) , among others .

Daniel Trefler (1995) developed a variant for countries with different production technologies.

literature

- Primary literature

- Interregional and International Trade. by Bertil Ohlin. Review by: James W. Angell. In: Political Science Quarterly. Volume 49, No. 1 (Mar., 1934), pp. 126-128. Published by: The Academy of Political Science. JSTOR 2143331 .

- Eli Filip Heckscher: The effect of foreign trade on the distribution of income. 1919.

- Secondary literature

- Robert E. Baldwin: The Development and Testing of Heckscher-Ohlin Trade Models. A review. MIT Press, Cambridge and London 2008, ISBN 978-0-262-02656-7 .

- Harry Flam, M. June Flanders: Introduction. In this. (Ed.): Heckscher-Ohlin Trade Theory. MIT Press, Cambridge and London 1991, ISBN 0-262-08201-2 , pp. 1-37.

- Ronald W. Jones: Eli Heckscher and the Holy Trinity. In: Ronald Findlay u. a. (Ed.): Eli Heckscher, International Trade, and Economic History. MIT Press, Cambridge and London 2006, ISBN 0-262-06251-8 , pp. 91-105.

- Paul Krugman , Maurice Obstfeld : International Economy. Theory and Politics of Foreign Trade. 6th edition. Pearson Studium, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-8273-7081-7 (on the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem see p. 105 ff.).

- Edward E. Leamer: The Heckschler-Ohlin model in theory and practice. Princeton University, Princeton 1995, ISBN 0-88165-249-0 .

- Bertil Ohlin: Interregional and International Trade. Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1933 (revised edition: Cambridge 1967; reprint of the first edition: Routledge, London et al. 1998, ISBN 0-415-15891-5 )

- Tadeusz M. Rybczynski : Factor Endowment and Relative Commodity Prices. In: Economica. 22, No. 88, 1955, pp. 336-341 ( JSTOR 2551188 ).

- Paul A. Samuelson : International Trade and the Equalization of Factor Prices. In: Economic Journal. 58, No. 230, pp. 163-184 ( JSTOR 2225933 ).

- Paul A. Samuelson: International Factor-Price Equalization Once Again. In: Economic Journal. 59, No. 234, pp. 181-197 ( JSTOR 2226683 ).

- Akira Takayama: International Trade. An approach to the theory. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York et al. a. 1972.

- Wolfgang Ströbele , Holger Wacker : Foreign trade. Introduction to theory and politics. Oldenburg Verlag, Munich 2000.

Notes and individual references

- ^ Paul R. Krugman, M. Obstfeld: Internationale Wirtschaft. 8th, updated edition, p. 90.

- ↑ Cf. Flam and Flanders 1991, p. 1. A complete translation of the dissertation into English can be found under the title The Theory of Trade in Harry Flam and M. June Flanders (eds.): Heckscher-Ohlin Trade Theory. MIT Press, Cambridge and London 1991, ISBN 0-262-08201-2 , pp. 71-214.

- ↑ See Jones 2006, pp. 91 ff .; Flam and Flanders 1991, p. 1. Heckscher's article (Heckscher 1919) originally appeared only in Swedish, a partial translation is contained in Howard S. Ellis (ed.): Readings in the theory of international trade. Blakiston, Philadelphia et al. a. 1949, pp. 272-300, for a full English translation, see Harry Flam and M. June Flanders (Eds.): The Effect of Foreign Trade on the Distribution of Income. MIT Press, Cambridge and London 1991, ISBN 0-262-08201-2 , pp. 39-69.

- ↑ See WJ Ethier: Moderne Außenwirtschaftstheorie, 1991, p. 137, pp. 140–141

- ↑ cf. M. Chacholades: International Economics. 1990, pp. 63-65.

- ↑ cf. JN Bhagwati, TN Srinivasan: Lectures on international Trade. 1983, p. 50.

- ↑ cf. M. Chacholades: International Economics. 1990, pp. 63-65.

- ↑ Thieß Petersen: Fit for the exam: foreign trade. UTB GmbH; Edition: 1st edition (October 4, 2012). ISBN 978-3-8252-3805-6 . P. 25.

- ↑ Harry P. Bowen, Edward E. Leamer, Leo Sveikauskas: Multicountry, multifactor tests of the factor abundance theory. In: The American Economic Review. 1987, pp. 791-809.

- ↑ Daniel Trefler: The case of the missing trade and other mysteries. In: The American Economic Review 1995, pp. 1029-1046.

Web links

- Heckscher-Ohlin-Handel - definition in Gabler Wirtschaftslexikon

- Heckscher-Ohlin theorem - definition in the Gabler Wirtschaftslexikon

- Heckscher-Ohlin model, Lerner diagram and factor content (PDF) - detailed presentation on the University of the Bundeswehr Munich

- Nobel Prize: Why Trade? - Heckscher-Ohin theory

- Economics Iowa State University: Leontief Paradox