Social network analysis

The social network analysis is a method of social research to collect and analyze social relationships and social networks . Social network analysis propagates a certain perspective on social phenomena that emphasizes their relational character. Connections and interdependencies between units (e.g. people or organizations) are in the foreground, not their individual attributes and properties. Social relationships and their structure thus become the unit of analysis itself. This is what distinguishes it from classical variable psychology. The social network analysis accordingly describes a relational research approach .

application

This recording and analysis is particularly used in psychology, for example in the context of organizational consulting and development processes, as well as in sociology. In the context of organizational psychology, a distinction is made between the analysis of inter-organizational and intra-organizational networks. In interorganizational networks, relationships between organizations are examined. These can relate to the exchange of goods and services, to personal connections such as memberships in supervisory boards and executive boards. Intra-organizational networks, i.e. networks within an organization, on the other hand, are usually used as an operationalization of the “informal organization” and thus differentiated from the formally established hierarchy.

history

Social network analysis was used in its early forms in the 1930s . She achieved her breakthrough with the establishment of block model analysis by Harvard structuralism, which resulted in the establishment of her own research direction. The block model analysis describes a method actors in "subsets" ( dt. Subset, subset ) to divide in order to subsequently relations or, optionally, a lack of these to identify between the "subsets." With the advent of modern software applications at the beginning of the 1990s, this method has become increasingly important in science and has enjoyed increasing popularity ever since.

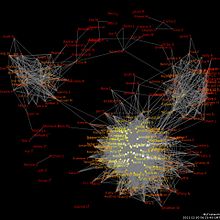

Formalization of network structures

Formal representations enable graph-theoretical interpretations of social networks. A network is represented as a graph with a delimited set of nodes , which represent the actors in a network, and edges , which represent the meaning of the relationship. This graph-theoretic representation is particularly clear. For more complex analyzes, it can be combined with sociometric and algebraic methods. The network is then translated into a sociomatrix , that is, into a tabular listing of the nodes and their relationships.

Measurements / analysis methods

Network analysis uses several methods with which social networks can be analyzed and described systematically and quantitatively. Thus, the metrics can help to understand complex networks. What all measures have in common is that they are interested in the relative position of individual actors in a network and not in certain attributes / characteristics of the people.

- Methods for centrality calculation ( English Centrality ): These aim to identify the most important, most active and most prominent actors in a network. A distinction is generally made between degree centrality, intermediate centrality and proximity centrality of actors:

- Degree centrality: Degree centrality expresses how many connections (relations) an actor has to other actors in the network. A distinction is made here between the connections originating from an actor and those directed towards an actor. The former are referred to as out-degree , the latter as in-degree . This distinction often results in an asymmetrical sociomatrix in which the sender-receiver roles are not evenly distributed. The degree centrality illustrates the basic principle of a network-analytical approach: The status of an actor in a network is determined on the basis of relationships to other actors, not on the basis of his individual attributes. However, degree centrality is sometimes not a good measure of the position of an actor in the entire network. Since only the connections to other actors are taken into account, actors with many connections ("local heros") are rated as more central than actors who are at critical / important points in the network. However, it does not have to be a disadvantage if you are only connected to two actors in a network instead of all of them, but these two offer access to important information, for example.

- Between centrality (ger .: betweenness centrality ): This measure takes into account not only direct but also indirect relationships in a network, and thus allows a more precise operationalization of some issues. Inter-centrality expresses the actor through which most information is conveyed in a network, for example, or through whom most of the communication takes place. Often, actors with a high level of inter-centrality connect two separate parts of a network. With the loss of the actor as a link, these would break down into two separate parts that no longer have anything to do with each other.

- Near centrality (ger .: Closeness Centrality ): This analysis method not only measures the connections of an actor to immediately obvious neighboring actors, but all actors in the network. Proximity centrality is also defined as the average path distance from one actor to the others in the network. To do this, you first add up the path distances from one node to all the others; the average “proximity” is then the reciprocal of this sum.

- Density (engl .: Density ): A measure for the characterization of networks or network parts is the density. It is an indicator of the total activity of a network. Density is defined as the ratio of the existing relationships to the maximum number of possible relationships. It can have a value between 0% (= there are no relationships) and 100% (= there is the maximum possible number of relationships). The maximum number of possible relationships results from the number of actors in a network. The density is also a measure of the selectivity of the network. The greater the size of an overall network, the greater the selection requirement: the more actors there are in a network, the greater the probability that the density in a network is low.

-

Clique Analysis (ger .: clique analysis ): Such procedures aim to divide a network into different sub-groups. Cohesive subgroups are sought, i.e. those regions of a network that are particularly strongly connected internally. The term clique is used in a similar way to colloquial language: A clique is a group of at least three people who are completely connected to one another. Each group member has a direct, undirected relationship with all other members. The meaning of the clique concept and related subgroup delimitations lies in formalizing the concept of the “social group” in terms of graph theory.

- n-cliques: describe a less strict definition of subgroups. Those subgroups are also taken into account that are created through indirect connections. The n-clique consists of all nodes that are at most n nodes apart. If you set n = 1, you are in the “strict” clique, if you choose higher values (usually 2 or 3), larger composite structures are recorded.

research object

With the social network analysis, a large number of different network types can be examined, for example:

- Communication networks comprise the exchange of information or knowledge between social actors.

- Evaluation and emotional networks include friendships, relationships of trust, but also antipathy between actors.

- Transaction networks describe the transfer of resources (for example workflow networks ).

Analysis software

- Pajek - network analysis and visualization program developed at the University of Ljubljana.

- UCINET - software package for analyzing social network data , developed by Linton Freeman, Martin Everett and Steve Borgatti.

- Gephi - open source software for analyzing and visualizing networks.

- MyNetworkmap - Online tool for surveying, analyzing and visualizing networks.

Web links

- Sociological Network Research Section of the German Society for Sociology

- German Society for Network Research

literature

- David Easley, Jon Kleinberg: Networks, Crowds, and Markets. Reasoning About a Highly Connected World. Cambridge 2010. ISBN 978-0-521-19533-1 .

- Markus Gamper, Linda Reschke (Ed.): Knots and Edges. Social network analysis in economic and migration research. transcript, Bielefeld 2010, ISBN 978-3-8376-1311-7 .

- Markus Gamper, Linda Reschke, Michael Schönhuth (Eds.): Knots and Edges 2.0. Social network analysis in media research and cultural anthropology. transcript, Bielefeld 2012, ISBN 978-3-8376-1927-0 .

- Tobias Müller-Prothmann: Leveraging Knowledge Communication for Innovation. Framework, Methods and Applications of Social Network Analysis in Research and Development. Peter Lang, Frankfurt a. M., Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-631-55165-7 .

- Thomas Schweizer: Patterns of social order: network analysis as the foundation of social ethnology. 2006, ISBN 3-496-02613-8 .

- Christian Stegbauer, Roger Häußling (Ed.): Handbuch Netzwerkforschung. VS-Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-15808-2 .

- Christian Stegbauer (Ed.): Network Analysis and Network Theory: A New Paradigm in the Social Sciences. VS-Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-15738-2 .

- Boris Holzer: network analysis. In: St. Kühl, P. Strodtholz, A. Taffertshofer (ed.): Handbook Methods of Organizational Research. Quantitative and Qualitative Methods. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2009, pp. 668–695.

- Jessica Haas, Thomas Malang (2010). Relationships and edges. In: C. Stegbauer, R. Häußling (Hrsg.): Handbuch Netzwerkforschung. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2010, pp. 89–98.

- Martin Kilduff, Daniel J. Brass: Appendix: Glossary of Social Network Technical Terms zu Organizational Social Network Research: Core Ideas and Key Debates. In: Academy of Management Annals. 4, 2010, pp. 68-70.

Individual evidence

- ^ Moreno, J. 1934: Who shall survive? New York.

- ↑ Jansen, D. 2006: Introduction to network analysis: basics, methods, research examples. Wiesbaden. Page 47

- ↑ Borgatti, S. / Mehra, A. / Brass, D. / Labianca, G. 2009: Network Analysis in the Social Sciences. In: Science 323: 892-895.

- ↑ Ricken, B./Seidl, D. 2010: Invisible networks. How social network analysis can be used for companies. Wiesbaden: pp. 61-90.

- ↑ B. Holzer: Network analysis. In: St. Kühl, P. Strodtholz, A. Taffertshofer (ed.): Handbook Methods of Organizational Research. Quantitative and Qualitative Methods. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2009, pp. 668–695.

- ↑ Knoke, D. / Kublinski, J. 1982: Network Analysis. London. P. 18.

- ↑ a b gephi.org

- ↑ Pajek on vlado.fmf.uni-lj.si

- ↑ sites.google.com