Clique analysis

The clique analysis is a method of social network analysis to examine closely networked subsets in social networks . With the help of computer programs, data sets from networks are evaluated in order to identify parts of the network that have a higher connection density than the rest of the network. Certain characteristics are ascribed to these cliques, for example the fact that the actors in the cliques are in particularly active exchange. Typical questions relate to the social environment, for example socialization and group formation processes among young people.

Clique analysis makes it possible to examine the relationship between actors. It is mainly used in sociology . The narrow concept of the clique is criticized for the fact that even a lack of connection can exclude large parts of the network from the clique, which is why expanded definitions of clique and further subgroup definitions are now used in network analysis.

object

The goal of a clique analysis is to identify cohesive subgroups within a network. In addition to the clique, there are also numerous extended concepts for subsets or subgroups of social networks that are used in the clique analysis method. These have in common that they have a greater cohesion and density than their surroundings in the network. A second criterion for subgroups is that their members are close to one another.

Concepts of subgroups in social networks

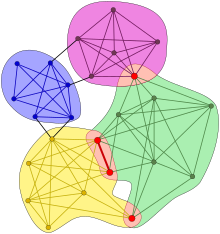

Social networks are often represented as a sociogram in the structure of a graph . The nodes of the graph stand for people or groups in the social network. The connections between the nodes are called edges and symbolize the social relationships between the nodes in the network.

clique

In terms of network analysis, clique is the maximum subset of at least 3 nodes of an undirected graph, for which it applies that every node is connected to every other node of the clique by an edge. In a social network, these are actors who are all interconnected.

n-clique

A clique is a clique in which the maximum distance between the parts of the clique is edges. The strict clique described above is therefore a 1-clique. A 2-clique includes all nodes that are connected by a maximum of 2 edges, with a 3-clique all nodes that are connected by 3 edges, and so on. Choosing such a modified clique definition has the advantage that 2 cliques are more robust against isolated missing connections than 1 cliques. In most cases, however, 2-cliques and not higher-grade cliques are used, since at higher grades the actual proximity of the actors in a clique to one another decreases sharply. (See section Criticism )

k-plex

The term plex was introduced by Seidman and Foster in 1978. An advantage of -Plexes compared to sociometric -Cliques is that -Plexes are much more robust with regard to missing connections. For a plex of the size , each node is directly connected to at least one node. This means that every 1-clique is also a 1-plex. However, this does not apply to cliques of a higher degree. In a 3-plex with 10 nodes, each of the 10 nodes is connected to 7 other nodes, a 3-plex of size 11 with 8 nodes.

n-clan

A clan is a clique that also has a maximum diameter of . This means that any node in the clan is at most edges away from any other .

component

If graphs are not fully connected, they can be separated into components. A component includes all nodes that are connected by any number of edges. It is the least strict concept compared to Clique, Plex and Clan.

Affiliation networks

In bimodal networks (also often English two-mode networks ) the nodes not only stand for actors, but also for categories. As a result, the subsets of the network can be formed via a common association with a category. This common node then stands for membership in an organization, for example.

Conducting a clique analysis

The analysis follows the scheme of quantitative social research, which consists of three steps: data collection, data processing and final evaluation. In practice, computers are used to analyze the data sets and identify the cliques, as manual evaluation is very time-consuming.

Even before the survey, it should be clear in which way the data should be evaluated in order to collect all the necessary information. If, for example, a directed graph is available, either software that can process it must be used, or a theoretical reduction to an undirected graph must be established. It must also be specified in the study design how cliques overlap should be dealt with.

Collection of data

The raw data for a network analysis can be collected in various ways.

- Surveys , for example with the help of a name generator, are a common form in research practice. This means that a respondent is asked to give the names of people around them. These people are then also interviewed and give further names. This creates a directed graph. Since surveys usually only ask for part of the relationships, typically three people, the size of the clique is limited, which makes the use of n-cliques of a higher degree recommended.

- observation

- As passive data collection, archives offer the possibility of examining historical networks.

- Metadata and the Internet have been a cheap and abundant source of network data since the proliferation of social media .

Preparation of the data

The data must be brought into a format in which the computer program used can process them ( machine readability ). Representations as a matrix (also called sociomatrix) are common.

| A. | B. | C. | D. | E. | F. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. | X | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| B. | 1 | X | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| C. | 1 | 1 | X | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| D. | 1 | 1 | 1 | X | 0 | 0 |

| E. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | X | 1 |

| F. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | X |

The table is structured in such a way that the nodes are entered both in the front row and in the header column. The Matrix form of a network table shows the matrix form of a directed graph . “0” stands for no connection. A connection from A to B is marked in the element in row A and column B with a "1". If it is a reciprocal connection, there is also a "1" in row B, column A. The table contains clique A, B, C, D. The corresponding graph is shown above in the figure "Directed network" .

Only reciprocal relationships (undirected edges) are relevant for clique analysis. The data must be prepared accordingly. Usually all one-sided relationships are removed for this purpose.

evaluation of the data

If the network is available in a machine-readable form, the data must be evaluated according to the theoretical concept. The clique analysis method is compatible with various research designs . The concrete evaluation depends on the question and the underlying theoretical concepts. Data is not to be equated with knowledge.

Relevant theories

In addition to the actor-network theory , a few other theories and considerations are relevant for the evaluation of a clique analysis:

- Social capital is primarily available to those actors who are well networked, for example part of a clique.

- The exchange theory in the version expanded by blue also applies to networks, whereby a connection between centrality and power can be shown.

- The diffusion theory is concerned with how information and knowledge spread. The group membership facilitates access to information.

- Social influence , also known colloquially as “peer pressure”, is particularly powerful in closely networked groups.

- Transivity (transferability), according to the proverbial phrase "Friends of my friends are also my friends".

- Balance - Actors who have the same contacts are very likely to choose each other too.

Overlap

The overlap poses a challenge when evaluating cliques. Overlapping cliques can be grouped into a social circle , as suggested by network researchers Kodushin and Alba in 1966. There is no general procedure. It is a methodological decision whether, for example, extended clique concepts are used, in which overlaps are neglected, or a different interpretation of the data is made.

Further analysis steps

Most studies rely on various structural properties of graphs and nodes. In addition to various measures for the centrality of nodes, the density of the network and the number of nodes connected are also included . Degree, examined. Further methods for the investigation of substructures of social networks are the triad census and the block model analysis .

history

The term clique was already used in scientific articles in the early 1940s to denote informal grouping of people. The graph theoretical version of cliques followed a few years later under the research strand of sociometry , a forerunner of social network research. In the 1960s, the first algorithms were presented with which the largest cliques in networks can be automatically determined (see also clique problem ). However, these algorithms were not implemented in scientific evaluation programs until the 1980s.

Up until the mid-1980s, a maximum of networks on the order of 50 nodes could be examined on home computers. In the 1990s, however, there were already a large number of programs with which networks can be analyzed and some of which were also able to examine larger networks. In the first decade after the turn of the millennium, more efficient algorithms were added. In addition to the greatly increased performance of the computers, this development contributed to expanding the area of workable questions and areas of application of clique analysis.

Since 2008 there have been approaches to use fuzzy logic to record cliques that are not clearly delimited.

Relevance of the clique analysis

The interest in clique analysis feeds on the assumption that in "köhasive subgroups" or cliques (in the sense of everyday language) mutual alignment and consensus building can be observed. It is also assumed that there is not only group formation there, but also a tendency towards homogeneity.

Other methods of social science data analysis cannot capture relationship structures. The network analysis provides an instrument for developing structural theories. Both small groups and corporate structures can be examined. Network analysis can examine the structure of all group formation. The concept of the clique is a very catchy concept for subgroups within networks. It is therefore particularly suitable for exploratory data analysis of the internal structure of social networks.

criticism

The main point of criticism of the clique analysis is the low robustness of 1-cliques. A single missing connection can exclude large parts of the network from a 1-clique. In practice it must be assumed that the networks are incomplete. This means that 1-cliques in large networks are usually small in relation to the overall network.

In the case of n-cliques of a higher degree, which are used as an alternative in response to these problems, one increasingly moves away from an understanding of the "clique" as a "group that is closely related": 2 cliques include friends of friends, 3- Cliques already people who are known "across three corners" (see small world phenomenon ).

In clique analysis, it is often assumed that homophilia can be observed in cliques . However, cliques in network analysis are initially only defined via a relational characteristic. A qualitative differentiation of the social relationships does not take place. All the children in a school class know each other, so they belong to the same clique. The relationship between best friends and the relationship between any children in the school class are treated equally. The construct of the clique cannot simply be used synonymously with the concept of the peer group , as in everyday language .

The data basis required for clique analysis is much more complex to collect than is necessary for other methods of empirical social research such as classic survey research. This also applies to other methods of network analysis to the same extent.

If a clique analysis is based solely on a graph-theoretical (sociometric) definition of clique, the network is only examined for structures that are internally defined. External relationships are not taken into account. The social relationship is reduced to exist or not, to “yes” or “no”. In addition, the cliques often overlap in large networks, the interpretation of which is unclear.

In addition, the general criticism of empirical social research can also be applied to network analysis in general and thus to clique analysis in particular.

Software for performing clique analyzes

- UCInet - one of the oldest programs for network analysis, which is widely used in research

- COMPLT by Richard Alba - software with an innovative method for handling clique clashes

- igraph - free software package for analyzing and displaying social networks, compatible with the statistical programming language R , among others

- Gephi - free software for visualizing networks that can also highlight cliques.

- Pajek - free software for analyzing and visualizing networks

See also

literature

- Dorothea Jansen: Introduction to network analysis: basics, methods, applications . Leske + Budrich, Opladen 1999, ISBN 3-8100-2262-4 , 8.1 Method of clique analysis.

- Peter Kappelhoff: clique analysis. The determination of internally connected subgroups in social networks . In: Franz Urban Pappi (Hrsg.): Techniques of empirical social research . 1st edition. Network Analysis Methods, No. 1 . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-486-44801-3 , p. 39-63 .

- Christina Prell: Social network analysis: history, theory & methodology . SAGE, Los Angeles 2012, ISBN 978-1-4129-4715-2 .

- Christian Stegbauer (Ed.): Network analysis and network theory: a new paradigm in the social sciences . 1st edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften / GWV Fachverlage, Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-15738-2 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Lloyd Allen Cook: An Experimental Sociographic Study of a Stratified 10th Grade Class . In: American Sociological Review . tape 10 , no. 2 , 1945, p. 250-261 , doi : 10.2307 / 2085644 , JSTOR : 2085644 .

- ↑ Christian Stegbauer, Roger Häußling: Introduction: Fields of application of network research . In: Handbuch Netzwerkforschung . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-15808-2 , p. 571-571 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-531-92575-2_48 .

- ↑ a b c Jansen, Dorothea .: Introduction to network analysis. Basics, methods, applications . Leske + Budrich, Opladen 1999, ISBN 3-8100-2262-4 , 8.1. Method of clique analysis.

- ↑ Marina Hennig… [et al.]: Studying social networks: a guide to empirical research . Campus-Verl, Frankfurt am Main 2012, ISBN 978-3-593-39763-4 , p. 132 .

- ^ A b c Peter Kappelhoff: Ciquenanalyse. The determination of internally connected subgroups in social networks . In: Fraz Urban Pappi (Hrsg.): Techniques of empirical social research . 1st edition. Network Analysis Methods, No. 1 . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-486-44801-3 , p. 51 .

- ↑ Marina Hennig… [et al.]: Studying social networks: a guide to empirical research . Campus-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2012, ISBN 978-3-593-39763-4 , p. 130 .

- ^ Mark Trappmann: structural analysis of social networks. Concepts, models, methods . 1st edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-531-14382-4 , pp. 71 .

- ↑ a b c Volker G. Täube: Cliques and other subgroups of social networks . In: Handbuch Netzwerkforschung . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-15808-2 , p. 397-406 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-531-92575-2_35 .

- ↑ Stephen B. Seidman, Brian L. Foster: A graph ‐ theoretic generalization of the clique concept . In: The Journal of Mathematical Sociology . tape 6 , no. 1 , 1978, ISSN 0022-250X , pp. 139-154 , doi : 10.1080 / 0022250X.1978.9989883 .

- ^ Franz Urban Pappi: Methods of Network Analysis . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-486-44801-3 , p. 50 f .

- ^ Robert J. Mokken: Cliques, clubs and clans . tape 6 . Klett-Cotta, 1980, ISBN 3-12-911060-7 , p. 353–366 , urn : nbn: de: 0168-ssoar-326164 .

- ^ Trappmann, Mark .: Structural analysis of social networks: concepts, models, methods . 1st edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-531-14382-4 , pp. 91 .

- ↑ Christina Prell: Social network analysis: history, theory & methodology . SAGE, Los Angeles 2012, ISBN 978-1-4129-4715-2 , pp. 162 .

- ^ Mark Trappmann: structural analysis of social networks. Concepts, models, methods . 1st edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-531-14382-4 , pp. 74 .

- ↑ Marina Hennig… [et al.]: Studying social networks: a guide to empirical research . Campus-Verl, Frankfurt am Main 2012, ISBN 978-3-593-39763-4 , p. 86 .

- ↑ Marina Hennig… [et al.]: Studying social networks: a guide to empirical research . Campus-Verl, Frankfurt am Main 2012, ISBN 978-3-593-39763-4 , p. 79 .

- ↑ Marina Hennig… [et al.]: Studying social networks: a guide to empirical research . Campus-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2012, ISBN 978-3-593-39763-4 , p. 82 .

- ↑ Christina Prell: Social network analysis: history, theory & methodology . SAGE, Los Angeles 2012, ISBN 978-1-4129-4715-2 , pp. 74 .

- ↑ Douglas A. Luke: A user's guide to network analysis in R . 1st edition. Springer International Publishing, Cham 2015, ISBN 978-3-319-23883-8 , pp. 18 , urn : nbn: de: 1111-20151215319 .

- ↑ Christina Prell: Social network analysis: history, theory & methodology . SAGE, Los Angeles 2012, ISBN 978-1-4129-4715-2 , pp. 158 .

- ↑ Different roles and mutual dependencies of data, information, and knowledge - An AI perspective on their integration . In: Data & Knowledge Engineering . tape 16 , no. 3 , September 1, 1995, ISSN 0169-023X , p. 191-222 , doi : 10.1016 / 0169-023X (95) 00017-M .

- ↑ a b c d e Christina Prell: Social network analysis: history, theory & methodology . SAGE, Los Angeles 2012, ISBN 978-1-4129-4715-2 , pp. 62 ff .

- ↑ a b Mark Trappmann: Structural analysis of social networks: concepts, models, methods . 1st edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-531-14382-4 , pp. 76 .

- ^ Richard D. Alba, Charles Kadushin: The Intersection of Social Circles: A New Measure of Social Proximity in Networks . In: Sociological Methods & Research . tape 5 , no. 1 , August 1, 1976, ISSN 0049-1241 , pp. 77-102 , doi : 10.1177 / 004912417600500103 .

- ↑ Tracy E. Strevey, W. Lloyd Warner, Paul S. Lunt: The Social Life of a Modern Community . In: The Mississippi Valley Historical Review . tape 29 , no. 4 , March 1, 1943, ISSN 0021-8723 , doi : 10.2307 / 1916643 .

- ^ Leon Festinger: The Analysis of Sociograms using Matrix Algebra . In: Human Relations . tape 2 , no. 2 . SAGE Publications Ltd, 1949, pp. 153-158 , doi : 10.1177 / 001872674900200205 .

- ^ Richard D. Alba: A graph ‐ theoretic definition of a sociometric clique . In: The Journal of Mathematical Sociology . tape 3 , no. 1 , July 1, 1973, ISSN 0022-250X , p. 113-126 , doi : 10.1080 / 0022250X.1973.9989826 .

- ^ Lothar Krempel: Network analysis and network theory: a new paradigm in the social sciences . Ed .: Christian Stegbauer. 1st edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften / GWV Fachverlage, Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-15738-2 , p. 216 .

- ^ Lothar Krempel: Network analysis and network theory: a new paradigm in the social sciences . Ed .: Christian Stegbauer. 1st edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften / GWV Fachverlage, Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-15738-2 , p. 217 .

- ^ Lothar Krempel: Network analysis and network theory: a new paradigm in the social sciences . Ed .: Christian Stegbauer. 1st edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften / GWV Fachverlage, Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-15738-2 , p. 218-219 .

- ↑ George B. Davis, Kathleen M. Carley: Clearing the FOG: Fuzzy, overlapping groups for social networks . In: Social Networks . tape 30 , no. 3 , July 2008, p. 201–212 , doi : 10.1016 / j.socnet.2008.03.001 .

- ^ Franz Urban Pappi: The network analysis from a sociological perspective . In: Franz Urban Pappi (Hrsg.): Techniques of empirical social research . 1st edition. Network Analysis Methods, No. 1 . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-486-44801-3 , p. 11-19 .

- ↑ Douglas A. Luke: A user's guide to network analysis in R . 1st edition. Springer International Publishing, Cham 2015, ISBN 978-3-319-23883-8 , pp. 107 , urn : nbn: de: 1111-20151215319 .

- ↑ Douglas A. Luke: A user's guide to network analysis in R . 1st edition. Springer International Publishing, Cham 2015, ISBN 978-3-319-23883-8 , pp. 109 , urn : nbn: de: 1111-20151215319 .

- ↑ Roger Häußling: Handbuch Netzwerkforschung . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften / Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-92575-2 , p. 402 .

- ↑ Christina Prell: Social network analysis: history, theory & methodology . SAGE, Los Angeles 2012, ISBN 978-1-4129-4715-2 , pp. 159 .

- ^ Christian Stegbauer: Handbook Network Research . 1st edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-15808-2 , p. 404 .

- ↑ Network Analysis and Network Theory: A New Paradigm in Social Sciences . 1st edition. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften / GWV Fachverlage, Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-15738-2 , p. 215 .

- ^ Heinz Harbach: Computer and human behavior Computer science and the future of sociology . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften / Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-531-18349-7 , p. 68 .

- ↑ analytictech.com

- ^ RD Alba: Computer program abstracts . In: Behavioral Science . tape 17 , no. 6 , 1972, ISSN 1099-1743 , pp. 566-575 , doi : 10.1002 / bs.3830170609 .

- ↑ igraph.org

- ↑ mrvar.fdv.uni-lj.si