Tabor light

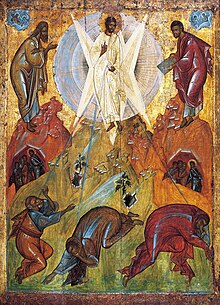

Taborlicht is a term from Christian spirituality. What is meant is the light that Peter , James and John saw according to the report of the three synoptic Gospels during the transfiguration of Christ on a mountain. This light is called Tabor light because, according to extra-biblical tradition, the mountain is Mount Tabor .

The Tabor light in hesychasm

Tabor light plays a central role in hesychasm , an originally Byzantine form of spirituality that was later spread throughout the entire Orthodox world. Hesychasm has been attested since the 12th century and experienced its first heyday in the Byzantine Empire in the 14th century. The center of the Hesychastic movement were the monasteries on Mount Athos .

The hesychasts (hesychasm practitioners) repeat the Jesus prayer for long periods of time . They strive for a state of complete external and internal calm (Greek hesychia ), which is a prerequisite for experiencing a special divine grace: Hesychasm teaches that the Tabor light can be perceived by those who pray. The doctrine that this light was not only seen by the three apostles, but is fundamentally accessible to everyone who prays in the right way, when he has cleansed his soul, is part of the core of hesychastic convictions.

The theological foundation and justification of the hesychastic doctrine of the Tabor light was created by the Athos monk Gregorios Palamas (1296 / 1297-1359), who is venerated as a saint in the Orthodox world. Palamas defended hesychasm in the " hesychasm controversy " against the criticism of Barlaam of Calabria . At several councils in Constantinople from 1341 to 1351, the Byzantine Church decided to first condemn the opponents of hesychasm and then to make the theoretical justification of hesychasm by Gregorios Palamas ("palamism") binding church doctrine. This decision is still authoritative in Orthodoxy. Hesychastic traditions, for example, have been powerful in 19th century Orthodox monasticism and in the Imjaslavie ( worship of the name of God) movement of the early 20th century. The renewed attention that the Imjaslavie movement is receiving in the Catholic-Orthodox dialogue of the present is also directed towards traditions such as that of the Tabor light.

In palamism, the view of the Tabor light is the climax of the possible experience of grace for those who pray hesychastically. The perceptions of light in the visions of the praying hesychasts are expressly equated with the light that the apostles saw when the Lord was transfigured. Palamas notes:

“The light that shone around the disciples during the metamorphosis of Christ and that now lets the spirit purified through virtue and prayer shine, is the light of the world to come [...] Isn't it obvious that there is only one and the same light that has appeared to the apostles on the tabor that now appears to the purified souls and in which the essence of future goods consists? "

Since the Tabor light is considered to be “uncreated”, i.e. not part of creation, the claim is made that it is a direct experience (Greek peira ) of God in his uncreated reality. Therefore, in depictions of hesychasm, there is often talk of a “divine vision”. However, according to the Palamas, this perception does not relate to God's inaccessible being, but only to his revealed and therefore perceptible energies (effective forces). In spite of this limitation, the doctrine of the view of the Tabor light has strongly offended the critics of the Palamitic hesychasm. In particular, the assertion that light and thus God's uncreated reality is perceived physically, i.e. that God is also perceived on the physical level, was already considered scandalous by his opponents at the time of the Palamas.

Within the late medieval hesychasm there was a trend that emphasized that not all visions of light are authentic. The influential Hesychast Gregorios Sinaites († 1346), a contemporary of the Palamas, warned against deceptive visions that were the product of the imagination, but he was also convinced that the Tabor light could and should be perceived in the present as well as in the time of Jesus.

literature

- Georg Günter Blum: Byzantine mysticism. Its practice and theology from the 7th century to the beginning of the Turkocracy, its continuation in modern times . Lit Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8258-1525-7 , pp. 348–353, 372–423

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Mark 9: 2-8; Matthew 17: 1-8; Luke 9.28-36.

- ^ Volkmar Fritz : Tabor . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Volume 32, Berlin 2001, pp. 595-596, here: 596.

- ↑ For example at the Institutum Studiorum Oecumenicorum (ISO) of the University of Friborg, Switzerland.

- ↑ Gregorios Palamas, Triad I 3.43; 203.26-205.2.28-31; quoted from the translation by Georg Günter Blum: Byzantinische Mystik , Berlin 2009, p. 385.

- ↑ A detailed account of the arguments in the controversies is provided by Georg Günter Blum: Byzantinische Mystik , Berlin 2009, pp. 368–423.

- ↑ Georg Günter Blum: Byzantinische Mystik , Berlin 2009, pp. 337f., 348–353.