Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire , shortened even Byzantium , or - because of the historical origin - the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium was an empire in the eastern Mediterranean . It emerged in the course of late antiquity after the so-called division of the empire of 395 from the eastern half of the Roman Empire . The empire ruled from the capital Constantinople - also known as "Byzantium" - extended from Italy and the Balkan Peninsula to the mid-sixth century during its greatest expansionArabian Peninsula and North Africa , but has been largely confined to Asia Minor and Southeastern Europe since the seventh century . The empire ended with the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans in 1453.

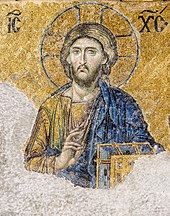

The history of the Byzantine Empire was marked by a defensive battle on the borders against external enemies, which put considerable strain on the empire's forces. Until the late period, when the empire no longer had sufficient resources, phases of expansion (after territorial losses in the seventh century, conquests in the tenth and eleventh centuries) alternated with phases of retreat. Internally (especially up to the ninth century) there were repeated theological disputes of varying degrees as well as isolated civil wars, but the state foundation, which was based on Roman structures, remained largely intact until the early thirteenth century. Culturally, Byzantium left behind important works of law , literature and art for the modern age . Byzantium also played an important mediating role due to the more strongly preserved ancient heritage. With regard to the Christianization of Eastern Europe , related to the Balkans and Russia, the Byzantine influence was also of great importance.

Definition and history of concepts

The Byzantinist Georg Ostrogorsky characterized the Byzantine Empire as a mixture of Roman state , Greek culture and Christian belief . The term Byzantine Empire , derived from the capital, is only common in modern research, but was not used by contemporaries of the time, who instead of "Byzantines" continued to refer to "Romans" (in modern research as " Rhomeans ") or (in Latin West) spoke of "Greeks".

In modern research, the history of the Byzantine Empire is divided into three phases:

- the late antique-early Byzantine period (around 300 to the middle of the 7th century), in which the empire as the eastern half of the Roman Empire was still shaped by the ancient Roman Empire and controlled the entire eastern Mediterranean as an intact great power ;

- the Middle Byzantine period (middle of the 7th century to 1204/1261), in which the now completely Graecised empire was consolidated again after major territorial losses and was still an important power factor in the Mediterranean;

- the late Byzantine period (1204/1261 to 1453), in which the empire shrank to a city-state and no longer played a political role in the region.

In addition to this traditional periodization, there are also considerations that deviate from it; Thus, in recent research there is an increasing tendency to have the "Byzantine" history in the narrower sense only begin with the late sixth or seventh century and to assign the time before that to (late) Roman history . Although this position is not without controversy, in practice the Eastern Roman history before the early 7th century was in fact mainly dealt with by ancient historians , while most of the Byzantinists are now concentrating on the subsequent period.

The Byzantines - and the Greeks to the 19th century - considered and called themselves "Romans" ( Ῥωμαῖοι Rhomaioi ; see. Rhomäer ). The word "Greeks" ( Ἕλληνες Héllēnes / Éllines ) was used almost exclusively for the pre-Christian, pagan Greek cultures and states. It was not until 1400 that some educated Byzantines such as Georgios Gemistos Plethon also called themselves "Hellenes".

The terms "Byzantine" and "Byzantine Empire" used today are of modern origin. Contemporaries always spoke of the Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων ( Basileia ton Rhōmaíōn , Vasilia ton Romäon "Empire of the Romans") or Ῥωμαικὴ Αὐτοκρατορία ( Rhōmaikḗ Autokratoría , Romaikí Aftokratoría "Roman dominion" or "Roman Empire", which is the direct translation of the Latin Imperium Romanum into Greek). According to their self-image, they were not the successors of the Roman Empire - they were the Roman Empire. This is also made clear by the fact that the terms “Eastern Roman” and “ Western Roman Empire ” are of modern origin and, according to contemporary opinion, there was only one empire under two emperors as long as both parts of the empire existed.

Formally, this claim was justified because there had been no break in the east as in the west and Byzantium continued to exist in a far more seamless state following the late antiquity, which only gradually changed and led to a Greekization of the state under Herakleios . However, even before that, the dominant identity of the Eastern Roman Empire, Greek and Latin, was only the language of rule used in the army, at court and in administration, not in everyday life. Ancient Greek and, since the turn of the century, Middle Greek , phonetic almost identical to today's Greek, not only replaced Latin as the official language since Herakleios , but was also the language of the church , literary language (or cultural language) and commercial language .

The Eastern Roman and Byzantine empires only lost their Roman and late antique character during the course of the Arab conquests in the seventh century. During its existence it saw itself as the immediately and only legitimate, continuing Roman Empire and derived from it a claim to sovereignty over all Christian states of the Middle Ages . Although this claim was no longer enforceable by the 7th century at the latest, it was consistently upheld in state theory .

Political history

Late Antiquity: The Eastern Roman Empire

The roots of the Byzantine Empire lie in Roman late antiquity (284–641). The Byzantine Empire was not a re-establishment, rather it is the eastern half of the Roman Empire , which existed until 1453 , which was finally divided in 395, i.e. the direct continuation of the Roman Empire . The related question of when Byzantine history actually begins cannot be answered unequivocally, however, as different research approaches are possible. Particularly in older research, the reign of Emperor Constantine the Great (306 to 337) was often seen as the beginning , while in more recent research the tendency predominates, only from the 7th century onwards as "Byzantine" and the period before that to be characterized as clearly belonging to late antiquity, although this is not undisputed either.

In a power struggle in the empire that lasted from 306 to 324, Constantine prevailed as sole ruler (in the West since 312), reformed the army and administration and consolidated the empire externally. As the first Roman emperor, he actively promoted Christianity ( Constantinian turn ) , which had an enormous impact; on the other hand, he created the later capital of the Byzantine Empire. Between 325 and 330 he had the old Greek polis of Byzantium generously expanded and renamed it Constantinople after himself . Before that, emperors had sought residences that were closer to the threatened imperial borders and / or were easier to defend than Rome, which after the brief reign of Emperor Maxentius at the latest was no longer the seat of the emperors, but only the ideal capital. However, in contrast to other royal cities, Constantinople received its own senate, which under Constantine's son Constantius II was formally equal to the Roman one. In the period that followed, the city developed more and more into the administrative focus of the eastern part of the empire. Towards the end of the 4th century even the names Nova Roma and Νέα ῾Ρώμη (Néa Rhṓmē) came up - the "New Rome". Despite this deliberate contrast to the old capital, ancient Rome continued to be the point of reference for imperial ideology. Since the time of Emperor Theodosius I , Constantinople was the permanent residence of the Roman emperors ruling in the east.

After Constantine's death in 337 there were mostly several Augustis in the empire who were responsible for ruling certain parts of the empire. At the same time, however, the unity of the Imperium Romanum was never questioned, rather it was a question of a multiple empire with regional division of tasks, as had become customary since Diocletian . Constantius II (337 to 361), Valens (364 to 378) and Theodosius I (379 to 395) ruled the east . After the death of Theodosius, who was the last emperor to actually rule the entire empire for a short time in 394/395, the Roman Empire was again divided into an eastern and a western half under his two sons Honorius and Arcadius in 395 . Such "divisions" of the empire had happened many times before, but this time it turned out to be final: Arcadius, who resided in Constantinople, is therefore considered by some researchers to be the first emperor of the Eastern Roman or Early Byzantine Empire. Nevertheless, all laws continued to apply in both halves of the empire (they were mostly enacted in the name of both emperors), and the consul of the other part was recognized. Conversely, both imperial courts rivaled for priority in the entire empire during the fifth century.

In the late fourth century, at the time of the beginning of the so-called Great Migration , the eastern half of the empire was initially the target of Germanic warrior groups such as the West and Ostrogoths . In the Battle of Adrianople in 378 the Eastern Roman army suffered a heavy defeat against mutinous (Western) Goths, who were then assigned in 382 by Theodosius I south of the Danube as formally alien Foederati land. Since the beginning of the fifth century, however, the external attacks have increasingly been directed towards the militarily and financially weaker western empire , which at the same time sank into endless civil wars that slowly decayed. Whether the Germanic warriors played a decisive role in the fall of West Rome is very controversial in recent research. In the east, on the other hand, it was possible to maintain extensive domestic political stability. Ostrom only had to fend off the attacks of the New Persian Sassanid Empire , Rome's only rival of equal rank , with whom, however, between 387 and 502 there was almost constant peace. In 410 the city of Rome was plundered by mutinous Visigothic foederati , which also had a clear shock effect on the Romans in the east, while the eastern half of the empire, apart from the Balkans , which repeatedly crossed warrior associations, remained largely unmolested and, above all, internal peace ( pax Augusta ) all in all could be true. Ostrom tried hard to stabilize the western half and repeatedly intervened with money and troops. The unsuccessful naval expedition against the Vandals 467/468 (see Vandal Campaign ) was largely carried out by Ostrom. But in the end the East was too busy with its own consolidation to be able to stop the decline of the Western Empire.

In the later fifth century the Eastern Empire also faced serious problems. Some politically significant positions were dominated by soldiers, not infrequently men of “barbaric” origin (especially in the form of the magister militum Aspar ), who were becoming increasingly unpopular: there was a danger that in East Stream, as had already happened in the West was that the emperors and the civil administration would come permanently under the domination of powerful military. Under Emperor Leo I (457-474), attempts were therefore made to neutralize Aspar's followers , which mainly consisted of foederati , by playing against them in particular Isaurians , the inhabitants of the mountains of southeast Asia Minor, that is, members of the empire. Leo also set up a new imperial bodyguard, the excubitores , who were personally loyal to the ruler; there were also many isaurians among them. In the form of Zeno , one of them was even able to ascend the imperial throne in 474 after Aspar was murdered in 471. In this way, the emperors gradually managed to regain control of the military between 470 and 500. Because under Emperor Anastasios I , the growing influence of the Isaurians could be pushed back again with great effort until 498. In more recent research, the view is held that the ethnicity of those involved in this power struggle actually played a subordinate role: It was not about a conflict between “barbarians” and “Romans”, but rather about a struggle between the imperial court and the army leadership, in which the emperors were finally able to assert themselves. The army continued to be shaped by foreign, often Germanic, mercenaries; From then on, however, the influence of the generals on politics was limited, and the emperors regained considerable freedom of action.

Around the same time, the empire ended in the west, which had already increasingly lost power to the high military in the late 4th century, so that the last western emperors in fact hardly ruled independently; In addition, the most important western provinces (above all Africa and Gaul) were gradually lost to the new Germanic rulers in the 5th century . The powerless last Western Roman emperor Romulus Augustulus was deposed in 476 by the military leader Odoacer (the last emperor recognized by Ostrom was Julius Nepos , who was murdered in Dalmatia in 480 ). Odoacer submitted to the Eastern Emperor. From then on he was de iure again the sole ruler of the entire empire, although the western regions were in fact lost. Most of the empires that now formed under the leadership of non-Roman reges on the ruins of the collapsed western empire, recognized the (Eastern) Roman emperor for a long time at least as their nominal overlord. At the turn of the sixth century, Emperor Anastasios I also strengthened the empire's financial strength, which benefited the later expansion policy of Eastern Europe.

In the sixth century, under Emperor Justinian (527-565), the two Eastern Roman generals Belisarius and Narses conquered large parts of the Western Roman provinces - Italy , North Africa and southern Spain - and thus restored the Roman Empire for a short time on a smaller scale. But the wars against the empires of the Vandals and Goths in the west and against the mighty Sassanid empire under Chosrau I in the east, as well as an outbreak of the plague that struck the entire Mediterranean world from 541 onwards , significantly undermined the substance of the empire. During the reign of Justinian, who was the last Augustus to have Latin as his mother tongue, Hagia Sophia was also built, for a long time the largest church in Christendom and the last great building in ancient times . Likewise, in 534 there was a comprehensive and powerful codification of Roman law (later known as the Corpus iuris civilis ). In the religious-political sector, the emperor was unable to achieve any sweeping successes despite great efforts. The ongoing tensions between Orthodox and Monophysite Christians, in addition to the empty treasury left by Justinian, represented a heavy burden for his successors. (Ostrogorsky), certainly still belongs to the ancient world. Under his successors, the importance and spread of the Latin language in the empire continued to decline, and with the establishment of the exarchates in Carthage and Ravenna , Emperor Maurikios for the first time adopted the late ancient principle of separating civil and military competences, albeit in the core area of the Reiches still clung to the conventional form of administration.

From the second half of the sixth century, empty coffers and enemies appearing on all fronts again brought the empire into serious trouble. During the reign of Justinian's successor Justin II , who provoked a war with Persia in 572, suffered a nervous breakdown as a result of his defeat and went mad, the Lombards occupied large parts of Italy as early as 568. Meanwhile, the Slavs invaded the Balkans from around 580 and mostly colonized it by the end of the seventh century. With the violent death of the emperor Maurikios in the year 602, who had been able to make an advantageous peace with the Sassanids in 591 and had taken energetic action against the Slavs , the military crisis escalated. Maurikios was the first Eastern Roman emperor to succumb to a usurper, and his ill-reputed successor Phocas did not succeed in stabilizing the position of the monarch. From 603 onwards, the Sassanid Persians under Great King Chosrau II temporarily gained control over most of the eastern provinces. By 620 they had conquered Egypt and Syria , and thus the richest eastern Roman provinces, and in 626 they even stood before Constantinople . Ostrom seemed to be on the verge of doom, as the Avars and their Slavic subjects were also advancing into imperial territory in the Balkans . These processes were favored by a civil war between Emperor Phocas and his rival Herakleios . The latter was able to prevail in 610 and, after a hard struggle, also brought about the turning point in the war against the Persians: In several campaigns from 622 onwards, he invaded Persian territory and defeated a Sassanid army at the end of 627 in the battle of Nineveh . Although the Sassanids had not been decisively defeated militarily, Persia was now also threatened on other fronts and therefore wanted peace in the west. The unpopular Chosrau II was overthrown and his successor made peace with Ostrom. Persia vacated the conquered territories and soon sank into chaos due to internal power struggles. After this tremendous effort, however, the strength of the Eastern Roman Empire was exhausted. The Senate aristocracy, which had been an essential bearer of the late ancient traditions, had also been severely weakened under Phocas. Control over most of the Balkans was lost.

Herakleios had the victory over the Persians and the salvation of the empire nevertheless lavishly celebrated and probably exaggerated his success. But the Eastern Roman triumph was short-lived. The military expansion by their new Muslim faith driven Arabs , which began in the 630 model-years, had not oppose the kingdom after the long and exhausting war against Persia much. Herakleios had to experience how the Oriental provinces, which had only just been vacated by the Sassanids, were lost again; forever this time. In the decisive battle of Yarmuk on August 20, 636, the East Romans were subject to an army of the second caliph ʿUmar ibn al-Chattāb , and the entire south-east of the empire, including Syria, Egypt and Palestine , was completely lost by 642; by 698 they lost Africa with Carthage .

The Middle Byzantine era

The Seventh Century: From the Eastern Roman to the Byzantine Empire

After 636, Ostrom stood on the edge of the abyss. In contrast to its long-standing rival, the Sassanid Empire , which went under in 642/651 despite fierce resistance, the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire was at least able to successfully defend itself against a complete Islamic conquest. The imperial troops , who had previously defended the Middle Eastern provinces, had to retreat to Asia Minor , which was ravaged by Arab attacks (raids) . In the course of the seventh century, As a result of Islamic expansion , Byzantium even temporarily lost its naval control in the eastern Mediterranean (defeat at Phoinix 655) and was also able to hold Asia Minor with difficulty, while Slavs and Bulgarians oppressed the empire in the Balkans and the imperial rule here limited a few places. Around 700, the eastern Romans were essentially reduced to a rump state with Asia Minor, the area around the capital, some areas in Greece and Italy. The loss of Egypt in 642 was the hardest blow for Byzantium, as the high economic output (Egypt was the province with the highest tax revenue) and the grain of Egypt were essential for Constantinople.

What the empire lost in territories, however, it gained in internal uniformity, especially since a population loss has been demonstrable since the late 6th century. For centuries, ancient civilization had been shaped by the existence of numerous large and small towns - póleis ; that time ended now. Most cities were abandoned or shrunk to the size of fortified villages called kastra . The old, urban upper class also went under; Under the conditions of the fierce fighting, a new military elite took its place, whose members were no longer interested in the maintenance of ancient educational goods.

The lost southern and oriental provinces were culturally very different from the north and, since the fifth century, had mostly belonged to the Eastern Orthodox , Monophysite churches, which had been in dispute with the Greek Orthodox Church of the northern provinces since 451. This conflict was perhaps one of the reasons for the early acceptance of the new Muslim masters in Syria and Egypt (which, however, is again highly controversial in recent research). In any case, the north of the empire, which remained under imperial control, achieved greater unity and greater readiness to fight. The price to be paid for survival, however, was the permanent loss of two-thirds of the empire and most of the tax revenue.

By already making Greek, which was the dominant language in the remaining territories of the empire, the sole official language, Herakleios took an important step on the way to the Byzantine Empire of the Middle Ages . Many researchers therefore only see this emperor, who gave up the title of imperator and henceforth officially called himself the basileus , the last (east) Roman and also the first Byzantine emperor. There is agreement that the seventh century as a whole marks a deep turning point in the history of the empire. The only disagreement is whether the three centuries before should be counted as part of Roman or Byzantine history; as this period is now referred to as late antiquity and understood as an epoch of transformation, the question of the “beginning” of Byzantium has lost a lot of its relevance. What is certain is that byzantinists as well as many ancient historians deal with Eastern Roman history up to Herakleios , but not with the following centuries, which represent the field of work of Byzantine studies .

The traditional structures of the state and society from late antiquity were often no longer appropriate to the radically changed situation. In any case, it is surprising that Byzantium survived the decades-long struggle for survival against an enormous hostile force. An important factor for this was - in addition to repeated internal Arab disputes and the geographical peculiarities of Asia Minor - the new system of military provinces, the so-called themes . The themes were very likely created after the reign of Herakleios (different from the older research) in order to counter the constant attacks and decay of urban life outside the capital. Overall, the following applies to this phase: tendencies that had already existed for a long time came into full effect after 636 in many areas of the state and society. At the same time, numerous strands of tradition ended - the late antique phase of the Eastern Roman Empire came to an end, and the Byzantine Empire of the Middle Ages came into being.

The period from the middle of the seventh to the late eighth century was largely characterized by heavy defensive battles, in which the initiative lay almost exclusively with the enemies of Byzantium. Emperor Konstans II moved his residence to Syracuse , Sicily , from 661 to 668 , perhaps to secure naval rule against the Arabs from there, but his successors returned to the east. In 681, Emperor Constantine IV. Pogonatos had to recognize the newly founded Bulgarian empire in the Balkans. Around 678 Constantinople was first sieged by the Arabs , who were repulsed by using the so-called Greek fire , which even burned on the water. In modern research, however, the later source reports are increasingly questioned; Wave-like attacks and sea blockades are more likely, but not a regular siege of the capital. In the period that followed, the empire remained limited to Asia Minor, with areas in the Balkans and Italy, and up to 698 in North Africa.

The eighth and ninth centuries: defensive battles and iconoclasts

Emperor Justinian II , during whose reign Byzantium went on the offensive at least in part, was the last monarch of the Heraklean dynasty. As part of a practice that was often repeated later, Slavic settlers were deported from the Balkans to Asia Minor and settled there. The aim was to strengthen the border defense, but in the period that followed, desertions occurred again and again ; Similarly, some groups of the population were transferred from Asia Minor to the Balkans. Justinian fell victim to a conspiracy in 695, was mutilated (his nose was cut off ) and sent into exile, where he married a princess of the Turkic Khazars . He eventually came back to power with Bulgarian support before he was killed in 711.

The most threatening siege of Constantinople by the Arabs took place in 717–718 ; only thanks to the skills of Emperor Leo III. , the successful naval operations (with the Byzantines using the Greek fire ) and an extremely harsh winter that made difficult for the Arabs, the capital was able to hold on. In 740 the Arabs at Akroinon were decisively defeated by the Byzantines. Although the defensive struggles against the Arabs continued, the existence of the Byzantine Empire was no longer seriously endangered by them. In the meantime, Byzantium was involved in heavy fighting with the Slavs in the Balkans, who invaded the Byzantine territories after the collapse of the Avar Empire. Large parts of the Balkans were withdrawn from the Byzantine control, but in the following years the Slavs gradually regained areas of Greece that had been part of the Sklaviniai since the seventh century . The Slavs were subjugated and Hellenized, and people from Asia Minor and the Caucasus were resettled to Greece. In return, the empire on the Danube arose a new opponent in the form of the Bulgarians, who now successfully strived to form their own state.

Emperor Leo III. is said to have sparked the so-called picture dispute in 726 , which was to last for over 110 years and caused civil wars to flare up several times. However, the writings of the anti-image authors were destroyed after the victory of the icon modules , so that the sources for this time were almost exclusively written from the perspective of the winner and are accordingly problematic. Triggered by a volcanic eruption in the Aegean Sea, Leo 726 removed the icon of Christ above the Chalketor at the Imperial Palace. In recent research this is sometimes doubted, because due to the tendentious sources it is often unclear which steps Leo took exactly; possibly later actions were projected into the time of Leo. In this respect, it cannot even be unequivocally clarified how sharply pronounced Leo's hostility to images actually was. Apparently, Leo and his direct successors were not supporters of icon worship. Their military successes apparently made it possible for these emperors to replace icons (which at that time did not play such an important role in the Eastern Church as they do today) with representations of the cross, which could be recognized by all Byzantines, without great resistance. The fact that the abandonment of the worship of images was stimulated by influences from the Islamic area is often viewed with great skepticism today. The iconoclastic emperors were also staunch Christians who rejected icons precisely because, in their opinion, the divine essence could not be captured. In addition, the cross, which was supposed to replace the icons, was outlawed in the Islamic world. Modern research no longer assumes that Leo issued a downright ban on images or that there was even serious unrest, as the later iconodule sources suggest. Obviously, this first phase of the iconoclasm was not conducted with the harshness of the second phase in the ninth century.

Leo carried out several reforms internally and was also very successful militarily. In Asia Minor he took offensive action against the Arabs, with his son Constantine proving himself to be a capable commander. When Constantine succeeded his father as Constantine V on the throne in 741 , he put down the rebellion of his brother-in-law Artabasdos . Constantine was an opponent of image worship and even wrote several theological treatises for this purpose. By the Council of Hiereia in 754, the worship of images was also to be formally abolished, but Constantine took only a few concrete measures and even explicitly forbade vandalism of church institutions. Although militarily very successful (against both the Arabs and the Bulgarians), Constantine is described in the surviving Byzantine sources as a cruel ruler - wrongly and apparently because of his attitude towards the icons. Because other sources prove not only its relative popularity in the population, but also its immense reputation in the army . In terms of domestic politics, Constantine carried out several reforms and seems to have pursued a more moderate policy that was hostile to images. Several political opponents whom the emperor had punished were probably only later turned into martyrs, who were allegedly killed because of their image-friendly position. So Constantine was not a merciless iconoclast, as was assumed in older research with reference to the iconic reports.

Constantine's religious policy was followed by his son Leo IV , but he had to fight back several attempts at overthrow and died after only five years of reign in 780. For his underage son Constantine VI. his mother Irene took over the reign; However, it soon became apparent that the latter did not intend to give up power. Constantine was later blinded and died as a result. Irene was again pursuing an image-friendly policy. Under their rule, the universal claim of the Byzantine Empire with the imperial coronation of Charlemagne suffered severe damage. In 802 Irene, who had acted rather clumsily politically, was overthrown, with the result that the Leo III. founded Syrian dynasty (after the country of origin Leo III.) ended.

In terms of foreign policy, there was little to be done in the Balkans against the Bulgarians. In 811 even a Byzantine army led by Emperor Nikephoros I was destroyed by the Bulgarenkhagan Krum , and Nikephoros fell in battle. Only Leo V was able to come to an agreement with Khan Omurtag . It was also Leo V who took another anti-image course in 815 and thus initiated the second phase of iconoclasm. In the ninth and especially in the tenth century, some significant foreign policy successes were achieved, even if under the Amor dynasty (from Michael II's accession to the throne in 820) Byzantium initially lost territory ( Crete and Sicily fell to the Arabs). In addition, Michael II had to fend off an uprising that Thomas the Slav had started with the support of Paulicianism in the east of the empire and led to the walls of Constantinople in 820. Under Michael's son and successor Theophilos , there was finally a final flare-up of the iconoclastic dispute, which, however, under Michael III. (842–867), the last emperor of the Amorian dynasty, was finally defeated in 843. Under Michael III. The Bulgarians accepted Christianity - in its eastern form, with which the Byzantine culture, which was now flourishing more and more, also became the dominant culture for the Bulgarian Empire. The iconoclastic controversy was finally ended, while in Asia Minor the Paulikians were annihilated and several victories were won over the Arabs. Fleet expeditions to Crete and even Egypt were undertaken, but were unsuccessful. Byzantium had thus overcome the phase of pure defensive battles.

The Macedonian dynasty

Michael III rose 866 Basil to co-emperor , but Basil Michael left the following year to murder, ascended the throne himself and founded the Macedonian dynasty . Michael's memory has been badly vilified - wrongly, as recent research points out. Culturally, however, Byzantium experienced a new heyday (so-called Macedonian Renaissance ) such as in the time of Constantine VII , who was initially excluded from government business by Romanos I. Lakapenos . In terms of foreign policy, the empire gradually gained ground: Crete was recaptured under Nikephorus II Phocas ; border security in the east was now largely in the hands of the Akriten . John I Tzimiskes , who like Nikephorus II only ruled as regent for the sons of Romanos II , extended the Byzantine influence to Syria and for a short time even to Palestine , while the Bulgarians were held down. Byzantium seemed to be on the way to regional hegemonic power again.

The empire reached its peak of power under the Macedonian emperors of the tenth and early eleventh centuries. When the sister of Emperor Basil II married the Kiev Grand Duke Vladimir I in 987, the Orthodox faith gradually spread to the territory of the present-day states of Ukraine , Belarus and Russia . The Russian Church was under the Patriarch of Constantinople . Basileos II conquered the First Bulgarian Empire in years of fighting , which earned him the nickname Bulgaroktónos ("Bulgarian slayer "). In 1018 Bulgaria became a Byzantine province, and Basil's expansionary activity was also in the east.

Even so, the Byzantine Empire soon went through a period of weakness, largely caused by the growth of the landed nobility , which undermined the thematic system . One problem was that the standing army had to be replaced by partly unreliable mercenary units (which was bitterly avenged in 1071 in the battle of Manzikert against the Turkish Seljuks ). Only faced with its old enemies, such as the Abbasid Caliphate , it might have recovered, but around the same time new invaders appeared: the Normans , who conquered southern Italy (fall of Bari 1071), and the Seljuks, who mainly attacked Egypt were interested, but also undertook raids into Asia Minor, the most important recruiting area for the Byzantine army. After the defeat of Emperor Romanos IV at Manzikert against Alp Arslan , the Seljuk Sultan , most of Asia Minor was lost, among other things because internal battles for the imperial throne broke out and no common defense against the Seljuks was established. The loss of Asia Minor did not occur immediately after the defeat, however; rather, the Seljuks did not invade until three years later, when the new emperor failed to keep to the agreements made between Romanos IV and the sultan, and the Seljuks thus had an excuse to invade.

The time of the Komnen emperors

The next century of Byzantine history was marked by the dynasty Alexios I Komnenos , who came to power in 1081 and began to restore the army on the basis of a feudal system . He made significant advances against the Seljuks and in the Balkans against the Pechenegs, who were also Turkic . His call for Western help unintentionally brought about the First Crusade , because instead of the mercenaries that the emperor had asked for, there were independent armies of knights who acted independently of his orders. Alexios demanded that each of the crusader princes who intended to march through Byzantium with his army should take the oath of feudalism. But although this submission was accepted by most of the Crusader lords and the oath of fief was taken, they soon forgot the oath to Alexios.

Furthermore, relations became increasingly hostile after the First Crusade, in the course of which there had already been those tensions. The correspondence between the Fatimid ruler of Egypt and the Byzantine emperor Alexios caused further conflict . In a letter read by the Crusaders, Emperor Alexios expressly distanced himself from the Latin conquerors of the Holy Land . In view of the traditionally good and strategically important relations between the Fatimids and Byzantium, this was understandable, but it was also due to the fact that the concept of a " holy war " was rather alien to the Byzantines .

From the twelfth century, paradoxically, the Republic of Venice - once an outpost of Byzantine culture in the west until about the ninth century - became a serious threat to the integrity of the empire. Manuel I tried to take back the trade privileges granted against military support in the fight against the Normans and Seljuks by arresting all Venetians. Similar action was taken against the other Italian dealers. In 1185, numerous Latins were killed in a pogrom-like massacre. In the same year the Bulgarians rose north of the Balkan Mountains under the leadership of the Assenids and were able to establish the Second Bulgarian Empire in 1186 . Nevertheless, Byzantium also experienced a cultural boom during this time. Under the emperors John II Komnenus , the son of Alexios I, and his son Manuel I, the Byzantine position in Asia Minor and in the Balkans was consolidated. Manuel I not only had to deal with the attacks of the Norman Kingdom in southern Italy and the Second Crusade (1147–1149), he also pursued an ambitious western policy aimed at territorial gains in Italy and Hungary; he came into conflict with Emperor Friedrich I Barbarossa . In the east he was able to achieve success against the Seljuks. His attempt to completely subjugate their empire, however, ended in the defeat at Myriokephalon in 1176.

As a result, the Seljuks were able to expand their power to the neighboring Muslim empires (including the empire of the also Turkish Danischmenden ) in Asia Minor and also against Byzantium to the Mediterranean coast. Andronikos I , the last Emperor of the Comnen , established a brief but brutal reign of terror (1183–1185), as a result of which the system of government founded by Alexios I, which was based primarily on the involvement of the military aristocracy , collapsed. The powerful and tightly organized armed forces with which the empire under Alexios, Johannes and Manuel had successfully gone on the offensive for the last time also degenerated.

The empire was shaken by serious internal crises under the subsequent emperors from the house of the Angeloi , which finally led Alexios IV to turn to the crusaders and induce them to fight for the throne for him and his father. When the hoped-for payment failed to materialize, it came to a catastrophe: under the influence of Venice , the knights of the Fourth Crusade conquered and plundered Constantinople in 1204 and founded the short-lived Latin Empire . This permanently weakened Byzantine power and widened the gap between Orthodox Greeks and Catholic Latins .

The late Byzantine period

After the conquest of Constantinople by the participants in the Fourth Crusade in 1204, three Byzantine successor states emerged : the Empire of Nikaia , where Emperor Theodor I Laskaris maintained the Byzantine tradition in exile, the Despotate of Epirus and the Empire of Trebizond , which was already a priority among the descendants of the Comnenes the conquest of Constantinople had split off. Theodoros I. Laskaris and his successor John III. Dukas Batatzes succeeded in establishing an economically flourishing state in western Asia Minor and in stabilizing the border with the Seljuks, which had been in decline since their defeat by the Mongols in 1243. Based on this power base, the Laskarids were able to expand successfully in Europe, conquer Thrace and Macedonia and the rivals for the recovery of Constantinople (the empire of Epiros, which was greatly weakened after a defeat by the Bulgarians in 1230, and the Bulgarian empire, which was also Mongol invasion in 1241 was severely affected) knocked out of the field.

After the brief reign of the highly educated Theodoros II Laskaris , the successful general Michael VIII Palaiologos took over the reign of the underage John IV Laskaris , whom he finally had blinded and sent to a monastery, thus establishing the new dynasty of palaeologists who Empire should rule until his downfall.

Michael was able to defeat an alliance of his opponents (Despotate Epiros, Principality of Achaia , Kingdom of Sicily , Serbia and Bulgaria ) in the Battle of Pelagonia in Macedonia in 1259 and, by luck, recaptured Constantinople in 1261 . The empire was thus restored, but large parts of its former territory were no longer under his control, because the rulers who had established themselves in these areas after the collapse in 1204 were not inclined to subordinate themselves to Constantinople. Constantinople was also no longer the glamorous metropolis of yore: the population had shrunk considerably, entire districts had fallen into disrepair, and when the emperor moved in, there were still plenty of traces of the conquest of 1204 to be seen, but nowhere were signs of reconstruction to be seen. Byzantium was no longer the potent great power, but only a state of at most regional importance. Michael's main concern now was to secure the European possessions and above all the capital against renewed attempts at crusades from the west (especially by Charles I of Anjou , who replaced the Hohenstaufen in southern Italy); therefore, in 1274, he entered into the domestically highly controversial union of Lyon with the Western Church in order to prevent the Pope from supporting crusades. When Charles I of Anjou nevertheless prepared an attack, Byzantine diplomacy successfully started a revolt in Sicily in 1282, the Sicilian Vespers . In addition, however, the paleologists neglected the border defense in the east, which enabled the various Turkish principalities to expand into Byzantine Asia Minor, which the empire gradually lost in the 1330s.

While in Asia Minor various sovereign Turkish principalities ( Mentesche , Aydin , Germiyan , Saruchan , Karesi , Teke , Candar , Karaman , Hamid , Eretna and the Ottomans in Bithynia ) established themselves in the course of the dissolution of the Sultanate of the Rum Seljuks , pushed the paleologists in a last, powerful offensive against the Latin rule in Greece and annexed all of Thessaly by 1336 and in 1337 the despotate of Epirus, dominated by the Orsini family , directly into the Byzantine Empire. Meanwhile, Emperor Johannes V Palaiologos was confronted with the dramatic consequences of the Great Pest Pandemic, also known as the "Black Death" , in the years 1346 to 1353, which shook the foundations of the state. In addition, Byzantine made, although at its frontiers hard pressed by foreign powers, several civil wars , the longest ( 1321-1328 ) between Andronikos II. Palaiologos and his grandchildren Andronikos III. Palaiologos . Following this “example”, John V. Palaiologos and John VI. Kantakuzenos fought several power struggles ( 1341–1347 and 1352–1354 ) against each other; Both parties sought the help of their neighbors (Serbs, Bulgarians, but also Aydın and Ottomans). This enabled the Serbian empire under Stefan IV Dušan to rise to the dominant power of the Balkans in the years 1331-1355. After the Battle of Küstendil in 1330 , the Bulgarians became dependent on Serbia, and by 1348 Stefan gained hegemony over large parts of Macedonia, Albania , Despotate Epirus and Thessaly, which had previously been under the rule of the Byzantine emperor. With his coronation as Tsar of the Serbs and ruler of the Rhomeans , he also claimed the Byzantine imperial throne and rule over Constantinople. However, he did not even succeed in conquering the second Byzantine capital, Thessaloniki , and his Greater Serbian Empire fell into a conglomerate of more or less independent Serbian principalities ( despotates ) after his death in 1355 .

So while the Christian world of the Balkans was divided and feuded, the Ottomans had established themselves in Europe since 1354 and expanded into Byzantine Thrace, which they largely conquered in the 1360s. A preventive blow by the South Serbian King Vukašin Mrnjavčević in alliance with the Bulgarian Tsar Ivan Shishman of Veliko Tarnowo against the center of Ottoman rule in Europe, Adrianople , ended, despite numerical superiority, in the defeat at the Mariza in 1371. By defeating the two Slavic regional powers, the Ottoman sultan won part of Bulgaria and Serbian Macedonia, thus dominating the southern Balkans. Finally, in 1373, he forced the Bulgarian ruler to recognize the Ottoman supremacy . This example was followed by Byzantium, which had become a small state (Constantinople and its surrounding area, Thessaloniki and its surrounding area, Thessaly, some Aegean islands, Despotate Morea ) and the North Serbian Empire of Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović , who also became a vassal of the Ottomans. Byzantium asked the West for help several times and even offered church union , for example at the Council of Ferrara and Florence in 1439 , but this failed because of the resistance of the Byzantine population ("Better to wear the sultan's turban than the cardinal's hat").

After the battle of the Amselfeld in 1389 and the defeat of the western crusaders at Nicopolis in 1396, the situation of the empire seemed hopeless. It was not until the devastating defeat of the Ottomans against Timur at Angora in 1402, who was well-disposed towards the Byzantines (while attempting to besiege Constantinople in 1402, that Timur's negotiators appeared in Sultan's Bayezid I camp and asked him to give the Christian emperor back his territories, which he had given him "Stole") and the chaos in the Ottoman Empire as a result of the battle gave the Greeks a last respite. But the empire no longer had the possibility of averting the fatal blow by the Ottomans due to the deprivation of the necessary territorial base and resources, so that only the path of diplomacy remained. The loss of territory continued, however, as the European powers could not agree on any aid concept for the threatened Byzantium. After 1402 in particular, they saw no need for this, as the once potent Turkish Empire was apparently in a state of internal dissolution - this fatal error gave away the unique chance to eliminate the danger posed by the considerably weakened Osman dynasty for all time .

Sultan Murad II , under whom the consolidation phase of the Ottoman interregnum came to an end, took up the expansion policy of his ancestors again. After he had besieged Constantinople unsuccessfully in 1422 , he sent a raid against the Despotate of Morea, the imperial secondary school in southern Greece. In 1430 he annexed parts of the "Frankish" dominated Epirus by taking Janina , while Prince Carlo II. Tocco , as his liege recipient, had to come to terms with the "rest" in Arta (the Tocco dynasty was completely eliminated by the Ottomans until 1480 today's Greece - Epirus, Ionian Islands - ousted, whereby the rule of the "Franks" over central Greece, which had existed since 1204, with the exception of a few Venetian fortresses, finally came to an end). In the same year he occupied Thessaloníki, which had been dominated by the Venetians since 1423 and which the trade republic of Venice had acquired from Andronikos Palaiologos , a son of Emperor Manuel , because he believed that he could not assert the city alone against the Turks. Immediately he moved against the Kingdom of Serbia of Prince Georg Branković , who was formally a vassal of the Sublime Porte, as the latter refused to give his daughter Mara to the Sultan as a wife.

During an Ottoman punitive expedition towards the Danube , the Serbian fortress Smederevo was destroyed in 1439 and Belgrade besieged unsuccessfully in 1440 . The Ottoman setback near Belgrade called his Christian opponents on the scene. Under the leadership of Pope Eugen IV , who saw himself at the goal with the church union of Florence in 1439, a new crusade against the "infidels" was planned. Hungary, Poland, Serbia, Albania, even the Turkish emirate Karaman in Anatolia, entered into an anti-Ottoman alliance, but with the outcome of the Battle of Varna in 1444 under Władysław , King of Poland, Hungary and Croatia, and the second battle on the Amselfeld in 1448 under the Hungarian imperial administrator Johann Hunyadi , all hopes of the Christians to save the Byzantine Empire from an Ottoman annexation were finally dashed. On May 29, 1453, after almost two months of siege , the capital fell to Mehmed II. The last Byzantine emperor Constantine XI. died during the fighting for the city.

May 29 is still considered by the Greeks as an unlucky because it began the long Turkish domination during which only the following partial language acquisition religion remained as binding force. The start and end dates of the capital's independence, 395 and 1453, have long been considered the time limits of the Middle Ages. As a result, the remaining states of Byzantine origin were conquered: the Despotate Morea in 1460, the Empire of Trebizond in 1461 and the Principality of Theodoro in 1475. Only Monemvasia submitted to the Protectorate of Venice in 1464 , which was able to hold the city against the Turks until 1540. In terms of constitution, the city represented what remained of the “Roman Empire” over the centuries.

The fall of Byzantium was one of the turning points of world historical importance . The Byzantine Empire, which had proven to be one of the longest-lived in world history, was thus politically collapsed ( culturally, it continues to have an effect up to the present day); with him an era of more than two thousand years came to an end. However, due to the conquest of the Byzantine Empire and blockade of the Bosphorus as well as the land route to Asia by the Ottoman Turks, a new era began, which marked the age of European discoveries and the Renaissance (favored by Byzantine scholars who fled to Western Europe after the fall of Constantinople ). initiated.

Constitutional, economic and cultural-historical sketching

The Byzantine Empire had - in contrast to other empires of the Middle Ages - a tightly organized and efficient bureaucracy , the center of which was Constantinople, even after the invasion of the Arabs . Hence Ostrogorsky could speak of a state in the modern sense. In addition to an efficient administrative apparatus (see also offices and titles in the Byzantine Empire ), the empire also had an organized financial system and a standing army . No empire west of the Empire of China could dispose of such large amounts as Byzantium. Numerous trade routes ran through Byzantine territory and Constantinople itself functioned as an important trading center, from which Byzantium benefited considerably, for example through import and export tariffs (kommerkion). The economic power and charisma of Byzantium was so great that the golden solidus was the key currency in the Mediterranean between the fourth and eleventh centuries . The emperor, in turn, ruled almost unrestrictedly over the empire (which was still committed to the idea of universal power) and the church, and yet in no other state was there such a great opportunity for advancement into the aristocracy as in Byzantium.

Only Byzantium, according to the contemporary idea, was the cradle of “true faith” and civilization. In fact, the cultural level in Byzantium was higher, at least until the High Middle Ages, than in any other empire of the Middle Ages. The fact that much more of the ancient heritage was preserved in Byzantium than in Western Europe also played a role here; likewise the standard of education was for a long time higher than in the west.

In large parts, little is known about the "New Rome". Relatively few files have survived, and byzantine historiography is also partly silent , which began in late antiquity with Prokopios of Caesarea and in the Middle Ages had some important representatives with Michael Psellos , Johannes Skylitzes , Anna Komnena and Niketas Choniates (see source overview ). Even though only "ecclesiastical" sources are available for some periods, this should not lead to the assumption that Byzantium was a theocratic state . Religion was often decisive, but parts of the sources, and especially for the period from the seventh to the ninth centuries, are too poor to get a clear picture. Conversely, research has also abandoned the idea of a Byzantine Caesaropapism , in which the emperor ruled the church almost absolutely.

military

Byzantium had a standing army throughout its history, in stark contrast to the medieval empires in Europe. The Roman army of late antiquity was completely reorganized in the Middle Byzantine period. In the second half of the seventh century, fixed military districts ( subjects ) emerged, which for a long time were the cornerstones of the Byzantine defense against external enemies. The army and the navy were split up into a central unit in the capital and the local troops stationed in the provinces, with the four great themed armies of the seventh and eighth centuries each having about 10,000 men. Overall, the Byzantine army turned out to be a very effective armed force (admittedly dependent on the respective commanders and logistics), but its overall strength can only be roughly estimated. In the seventh century it should have been around 100,000 men, in the eighth century around 80,000 men and around 1,000 around 250,000 men. However, the Byzantine army lost its effectiveness over time, especially from the 13th century onwards, the troops were no longer able to withstand the external threat effectively. At that time Byzantium did not have sufficient financial resources and also had to rely heavily on mercenaries, which made the situation even worse. With the loss of central areas (especially in Asia Minor to the Turks), the Byzantine army shrank more and more and became a marginal size. The Byzantine Navy, which had played an important role in the Middle Byzantine period, hardly existed in the late Byzantine period.

Cultural continuation

After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, refugees from Byzantium, including numerous scholars, brought their scientific and technical knowledge and the ancient writings of the Greek thinkers to the western European cities, where they made a significant contribution to the development of the Renaissance . The Byzantine culture survived the longest on the then Venetian Crete , which went down in history as the so-called "Byzantine Renaissance". These remnants of the autonomous Hellenistic-Byzantine culture ended with the conquest of the island by the Ottomans in 1669.

To this day, the Byzantine culture continues, especially in the rite of the Eastern Orthodox churches. Through Byzantine missionary work, Orthodox Christianity spread among many Slavic peoples and is the predominant denomination in Eastern Europe and Greece, in parts of Southeast Europe and the Caucasus, and among most Arab Christians to the present day. Byzantine culture and thinking left a deep mark on all Orthodox peoples.

The Slavic empires in the Balkans and on the Black Sea adopted not only the Orthodox Church but also profane Byzantine customs. Above all Russia , Serbia , Ukraine and Belarus , but also to a lesser extent Bulgaria, should continue the legacy of the Byzantine Empire.

As early as the ninth century, the Rus came into contact with Byzantium, which - despite repeated attempts on the part of the Rus to conquer Constantinople - developed intensive economic and diplomatic relations between the Byzantine Empire and the Empire of the Kievan Rus, which in 988 led to the conversion of the Led Rus to the Orthodox faith. In the centuries that followed, numerous magnificent churches based on the Byzantine model were built on East Slavic territory. Thus, Russian architecture and art in addition to (usually later) Scandinavian and Slavic originally mainly Byzantine roots. The same applies in full to the architecture and art of Ukraine and Belarus.

After the fall of the Byzantine Empire, many parts of the Russian Muscovite Empire adopted Byzantine ceremonies . The Patriarch of Moscow soon gained a position whose importance was similar to that of the Patriarch of Constantinople . As the economically most powerful Orthodox nation, Russia soon saw itself as the third Rome in the succession of Constantinople. Ivan III , Ruler of the Grand Duchy of Moscow , married the niece of Constantine XI. , Zoe , and adopted the Byzantine double-headed eagle as heraldic animal. Ivan IV , known as "the terrible", was the first Muscovite ruler to be officially crowned tsar .

But the Ottoman sultans also regarded themselves as legitimate heirs of the Byzantine Empire, although the Seljuk and Ottoman Turks had been archenemies of the Rhomeans for centuries and had ultimately conquered the Byzantine Empire. Sultan Mehmed II already referred to himself as “Kayser-i Rum” (Emperor of Rome) - the sultans therefore deliberately placed themselves in the continuity of the (Eastern) Roman Empire in order to legitimize themselves. The Ottoman Empire, which developed in the struggle with Byzantium, had more in common with it than just geographical space. The historian Arnold J. Toynbee described the Ottoman Empire - albeit very controversial - as the universal state of the "Christian-Orthodox society". In any case, the Byzantine Empire did not find a constitutional continuation in him.

Last but not least, the cultural and linguistic legacy of Byzantium lives on in today's Greeks , especially in modern Greece and Cyprus as well as in the Greek Orthodox Church (especially in the Patriarchate of Constantinople in Istanbul). Until the beginning of the 20th century, the Greek settlement area also covered large parts with the Byzantine core countries.

Demographic conditions

The Byzantine Empire was a polyethnic state , which, in addition to Greeks , included Armenians , Illyrians and Slavs , and in late antique / early Byzantine times also Syrians and Egyptians (smaller parts moved into the core realm after the loss of these provinces) and always a Jewish minority. Most of the areas covered by the Byzantine Empire had been Hellenized for centuries , that is, they had been part of the Greek culture. Important centers of Hellenism such as Constantinople, Antioch , Ephesus , Thessaloniki and Alexandria were located here ; it was here that the orthodox form of Christianity developed . Athens continued to be an important cultural center in late antiquity until Emperor Justinian banned the local Neoplatonic school of philosophy in 529 . Subsequently, the demographic conditions shifted, since the most economically and militarily important areas besides the capital were the oriental provinces of the empire. When these were lost, Asia Minor played an important role, and the Balkans again only since the early Middle Ages . When Asia Minor fell partially to Turkish invaders after 1071 and finally in the 14th century , the decline began from a major to a regional power and finally to a small state.

The population in late antiquity was probably around 25 million, although only estimates are possible; Constantinople may have had up to 400,000 inhabitants during this period. The population figures declined as early as the middle of the 6th century as a result of epidemics and wars (exact numbers cannot be determined), an urban decline process followed, although from the 9th century there was again a demographic and economic revival. At the beginning of the 11th century, the empire probably had around 18 million inhabitants. The following period was marked by strong territorial losses, especially from the 13th century, and the number of inhabitants decreased accordingly; an irreversible tendency, with the capital becoming more and more depopulated.

Basics of reception

The older, western research opinion saw in Byzantium often only a decadent, semi-oriental " despotism ", such as Edward Gibbon . This image has long been discarded by John Bagnell Bury , Cyril Mango , Ralph-Johannes Lilie , John F. Haldon and others. It is now always pointed out that Byzantium, as a mediator of cultural values and the knowledge of antiquity, achieved invaluable achievements. It was also the “protective shield” of Europe for many centuries, first against the Persians and steppe peoples , and later against the Muslim caliphates and sultanates . Ironically, the Byzantine Empire was unable to perform this function until after the devastating sack of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204.

See also

- List of Byzantine emperors

- Offices and titles in the Byzantine Empire

- Byzantine art

- Byzantine architecture

- Byzantine currency

- Astrology in the Byzantine Empire

- Circus parties

Source overview

The narrative sources represent the basic structure of Byzantine history, especially since only a few documents survived the fall of Byzantium. For the late antique phase of the empire, Ammianus Marcellinus (who still wrote Latin), Olympiodoros of Thebes , Priskos , Malchos of Philadelphia , Zosimos and Prokopios of Kaisareia are to be mentioned. Agathias and Menander Protektor joined the latter . The histories written by Theophylactus Simokates can be regarded as the last historical work of antiquity . In the Middle Byzantine period until the beginning of the ninth century, historical works ( Traianos Patrikios ) were apparently also written , but these have not been preserved. But they were used by the chroniclers Nikephoros and Theophanes . Theophanes was followed by the so-called Theophanes Continuatus , and the so-called Logothetenchronik as well as the historical work of Leon Diakonos were created in the tenth century . Regional chronicles such as the Chronicle of Monemvasia should also be mentioned. Michael Psellos and Johannes Skylitzes wrote in the eleventh century . In the twelfth century, among others, Anna Komnena and Johannes Kinnamos . For the subsequent late Byzantine period, Niketas Choniates , Nikephoros Gregoras , Georgios Akropolites , Theodoros Skutariotes and Georgios Pachymeres are of particular importance. Finally, Laonikos Chalkokondyles , Doukas , Georgios Sphrantzes and Michael Kritobulos report on the last years of the empire .

- Overview works

- Leonora Neville: Guide to Byzantine Historical Writing. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2018. [from the 7th century, with updated notes on editions and secondary literature]

- Warren Treadgold: The Early Byzantine Historians . Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2007.

- Warren Treadgold: The Middle Byzantine Historians . Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2013.

In addition, a large number of hagiographical works are to be mentioned, as are the various specialist publications - for example in the medical, administrative ( Philotheos ) or military field, as well as the important Middle Byzantine lexicon Suda -, seals, coins and archaeological findings of great importance.

- Aids:

- Johannes Karayannopulos, Günter Weiß: Source studies on the history of Byzantium (324-1453). 2 volumes. Wiesbaden 1982.

literature

With regard to current bibliographic information, the Byzantine magazine is particularly important . In addition, see, among other things, the information in the yearbook of Austrian Byzantine Studies . One of the most important research institutions of Byzantine Studies is the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection (see also Dumbarton Oaks Papers ).

- reference books

- Falko Daim (Ed.): Byzanz. Historical and cultural studies manual. JB Metzler, Stuttgart 2016, ISBN 978-3-476-02422-0 .

-

Alexander Kazhdan (Ed.): Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium . Three volumes, Oxford University Press, New York 1991, ISBN 0-19-504652-8 .

(Basic lexicon, alternatively: LexMA; on late antiquity, see now also The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity ) -

Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Nine volumes. Munich – Zurich 1980–1998.

(With a strong focus on Byzantium, numerous articles here also come from proven experts.)- In it the main article: J. Koder, A. Guillou, J. Ferluga, A. Kazhdan, M. Borgolte, R. Hiestand, H. Ehrhardt, G. Weiß: Byzantine Empire . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA) . tape 2 . Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1983, ISBN 3-7608-8902-6 , Sp. 1227-1327 .

-

Prosopography of the Middle Byzantine period . First division (641–867). Published by the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences, based on preliminary work by Friedhelm Winkelmann , prepared by Ralph-Johannes Lilie, Claudia Ludwig, Thomas Pratsch, Ilse Rochow, Beate Zielke and others, seven volumes (Prolegomena + volumes 1–6), Berlin – New York 1998 -2001; Second division. Prolegomena + eight volumes. Berlin 2009 and 2013.

(Important prosopographical reference work. For the time before 641: The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire . ) - Alexis GC Savvides, Benjamin Hendrickx (Eds.): Encyclopaedic Prosopographical Lexicon of Byzantine History and Civilization (EPLBHC). Volume 1ff. Brepols, Turnhout 2007ff.

(Prosopographical manual not yet completed.) -

Herbert Hunger , Johannes Koder (Ed.): Tabula Imperii Byzantini . Vienna 1976ff.

(Basic historical and geographical representation of the core areas of the Byzantine Empire, structured according to individual regions. 13 volumes have been published so far, five more are currently being worked on.)

- Overview representations

-

Hans-Georg Beck : The Byzantine Millennium. CH Beck, Munich 1994.

(Insight into the "essence of Byzantium" through the presentation of various aspects of Byzantine society.) - Falko Daim, Jörg Drauschke (ed.): Byzantium - the Roman Empire in the Middle Ages. Volume 1: World of Ideas, World of Things , ISBN 978-3-88467-153-5 ; Volume 2, 1 and 2: Schauplätze , ISBN 978-3-88467-154-2 ; Volume 3: Periphery and Neighborhood , ISBN 978-3-88467-155-9 (monographs of the Römisch Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz Volume 84, 1–3) Verlag des Römisch Germanisches Zentralmuseums, Mainz 2010 (four-volume academic volume accompanying the special exhibition Byzantium. Splendor and Everyday Life ).

- Falko Daim, Jörg Drauschke (ed.): Byzanz - splendor and everyday life. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-7774-2531-3 .

- Alain Ducellier (Ed.): Byzantium. The empire and the city. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 1990.

(Easy to read overall presentation, in which not only political history, but also social and cultural history are taken into account. Original title: Byzance et le monde orthodoxe. Paris 1986.) - Timothy E. Gregory: A History of Byzantium. Malden / MA and Oxford 2005.

(Informative overview; specialist review .) - Michael Grünbart : The Byzantine Empire ( compact history ). Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2014, ISBN 978-3-534-25666-2 .

- John Haldon: The Byzantine Empire. Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-538-07140-3 .

(Relatively brief overview work.) - Judith Herrin: Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire. London 2007 / Princeton 2008.

(Unorthodox, thematically rather than chronologically structured and easy to read introduction.)- German: Byzantium. The amazing story of a medieval empire . Reclam Verlag, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-010819-2 .

- Liz James (Ed.): A Companion to Byzantium. Blackwell, Oxford et al. 2010.

-

Elizabeth M. Jeffreys , John Haldon, Robin Cormack (Eds.): The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies. Oxford 2008.

(Current collection of specialist articles on a multitude of different aspects of Byzantium and related research. Often rather short, but with a good bibliography.) - Andreas Külzer : Byzantium ( Theiss Knowledge compact series ). Konrad Theiss, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-8062-2417-7 .

-

Ralph-Johannes Lilie : Byzantium - The second Rome. Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-88680-693-6 .

(Probably the most comprehensive scientific account of the history of Byzantium in German.) - Ralph-Johannes Lilie: Byzantium. History of the Eastern Roman Empire 326–1453. Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-41885-6 .

(Very short, easy-to-understand overview) - Ralph-Johannes Lilie: Introduction to Byzantine History. Stuttgart et al. 2007.

(Excellent, up-to-date introduction that - albeit briefly - deals with the most important aspects of Byzantine history.) -

Cyril Mango (Ed.): The Oxford History of Byzantium. Oxford 2002, ISBN 0-19-814098-3 .

(Concise but useful and richly illustrated introduction.) -

John J. Norwich : Byzantium - Rise and Fall of an Empire. Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-549-07156-6 .

(Well legible popular scientific Byzantine chronicle, but without scientific claim.) -

Georg Ostrogorsky : History of the Byzantine State. ( Handbook of Classical Studies XII 1.2). Third edition. Munich 1963, ISBN 3-406-01414-3 .

(For a long time the valid standard work, but now out of date on many issues and therefore no longer recommended as a guide; as a special edition without scientific apparatus: Byzantine History 324 to 1453. Munich 1996, ISBN 3-406-39759-X .) -

Peter Schreiner : Byzanz ( Oldenbourg floor plan of history , volume 22). Third revised edition. Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-57750-1 .

(Good and concise introduction with research part; the third edition has been completely revised and expanded.) - Ludwig Wamser (ed.): The world of Byzantium - Europe's eastern heritage. Splendor, crises and survival of a thousand-year-old culture ( series of publications by the State Archaeological Collection , Volume 4). Book accompanying an exhibition of the State Archaeological Collection - Museum for Prehistory and Early History Munich from October 22, 2004 to April 3, 2005. Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8062-1849-8 .

- [Various eds.]: The New Cambridge Medieval History . Volume 1ff., Cambridge 1995-2005.

(Various articles in the various volumes, well suited as a first introduction. There also extensive literature references.) - The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire. Edited by Jonathan Shepard. Cambridge 2008.

-

Warren Treadgold : A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford University Press, Stanford 1997.

(Comprehensive, controversial and not unproblematic presentation due to partly very subjective evaluations. Contrary to the title, mainly the political history is depicted.)

- Epoch-specific representations - late Roman / early Byzantine times

- Alexander Demandt : The late antiquity ( handbook of ancient science III.6). Second edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007.

-

John F. Haldon : Byzantium in the Seventh Century. The Transformation of a Culture. Second edition. Cambridge 1997.

(Important study on the “transformation” of late ancient culture in the seventh century.) - James Howard-Johnston : Witnesses to a World Crisis. Historians and Histories of the Middle East in the Seventh Century. Oxford University Press, Oxford et al. 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-920859-3 .

-

Arnold Hugh Martin Jones : The Later Roman Empire 284-602. A Social, Economic and Administrative Survey. Three volumes paged throughout, Oxford 1964 (reprinted in two volumes, Baltimore 1986).

(Standard work) - AD Lee: From Rome to Byzantium AD 363 to 565. The Transformation of Ancient Rome. Edinburgh 2013.

- Epoch-specific representations - Middle Byzantine period

- Michael J. Decker: The Byzantine Dark Ages. London / New York 2016.

- Michael Angold : The Byzantine Empire, 1025-1204. Second edition. London – New York 1997.

- Leslie Brubaker, John F. Haldon: Byzantium in the Iconoclast era. c. 680-850. A history. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 2011, ISBN 978-0-521-43093-7 .

- Jean-Claude Cheynet (Ed.): Le Monde Byzantin II. L'Empire Byzantin (641-1204). Paris 2006.

- John F. Haldon: The Empire That Would Not Die. The Paradox of Eastern Roman Survival, 640-740. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) 2016.

- Warren Treadgold: The Byzantine Revival, 780-842. Stanford 1988.

- Mark Whittow: The Making of Byzantium, 600-1025. Berkeley 1996.

- Epoch-specific representations - late Byzantine period

- Jonathan Harris: The End of Byzantium . Yale University Press, New Haven 2010, ISBN 978-0-300-11786-8 .

- Donald M. Nicol : The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261-1453. 2nd Edition. Cambridge 1993.

- David Nicolle , John F. Haldon, Stephen R. Turnbull : The Fall of Constantinople. The Ottoman Conquest of Byzantium . Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2007, ISBN 978-1-84603-200-4 .

-

Steven Runciman : The Conquest of Constantinople. Munich 1966 (and reprints), ISBN 3-406-02528-5 .

(The standard work on the subject, albeit out of date in some details.)

- Special examinations

- Hélène Ahrweiler : L'idéologie politique de l'Empire byzantin. Paris 1975.

- Henriette Baron: For better or for worse. Humans, animals and the environment in the Byzantine Empire ( mosaic stones. Research at the RGZM , Volume 13). Verlag des RGZM, Mainz 2016, ISBN 978-3-88467-274-7 .

- Hans-Georg Beck : Church and theological literature in the Byzantine Empire. Munich 1959.

- Leslie Brubaker: Inventing Byzantine Iconoclasm . Bristol Classical Press, London 2012.

(Current introduction to the Byzantine iconoclasm.) - Lynda Garland: Byzantine Empresses. Routledge, London – New York 1999.

- John Haldon: Warfare, State and Society in the Byzantine World. Routledge, London-New York 1999, ISBN 1-85728-495-X .

(Extensive and in-depth study of the Byzantine military.) - John Haldon: The Byzantine Wars. 2001, ISBN 0-7524-1795-9 .

(Overview of the Byzantine Wars.) - John Haldon: Byzantium at War. 2002, ISBN 1-84176-360-8 .

(Popular scientific and richly illustrated introduction to the Byzantine military system.) - John Haldon (Ed.): A Social History of Byzantium. Blackwell, Oxford et al. 2009.

(An explicitly socio-historical presentation written by several respected researchers, therefore without taking political history into account.) -

Hans Wilhelm Haussig : Cultural history of Byzantium (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 211). 2nd, revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1966, DNB 456927646 .

(Older, but scientifically sound and very legible.) - Herbert Hunger : The high-level profane literature of the Byzantines. 2 vol., Munich 1978.

- Herbert Hunger: Writing and Reading in Byzantium. The Byzantine book culture. Munich 1989 (Introduction to the Material Aspects of Byzantine Literature).

- Anthony Kaldellis: Hellenism in Byzantium. Cambridge 2007.

- Johannes Koder : The habitat of the Byzantines. Historical-geographical outline of their medieval state in the eastern Mediterranean ( Byzantine historians , supplementary volume 1). Reprint with bibliographical supplements, Vienna 2001 (introduction to the historical geography of the Byzantine Empire).

- Henriette Kroll: Animals in the Byzantine Empire. Overview of archaeozoological research ( monographs of the RGZM , 87). Verlag des Römisch Germanisches Zentralmuseums, Mainz 2010. (Overview of domestic animal husbandry, hunting, bird and fishing as well as mollusc use. With a list of Byzantine sites for which archaeozoological investigations were carried out and a list of the domestic and wild animal species represented.)

- Angeliki E. Laiou , Cécile Morrisson : The Byzantine Economy ( Cambridge Medieval Textbooks ). Cambridge 2007 (Introduction to Byzantine Economic History).

- Angeliki E. Laiou (Ed.): The Economic History of Byzantium. Three volumes, Washington, DC, 2002 (standard work on Byzantine economic history; (online) ).

- Ralph-Johannes Lily : Byzantium and the Crusades. Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-17-017033-3 .

- John Lowden: Early Christian and Byzantine Art. London 1997.

- Jean-Marie Mayeur et al. (Ed.): The history of Christianity. Religion politics culture. Volumes 2-6. Special edition, Verlag Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2005 and 2007.

(Comprehensive presentation of the history of Christianity including the Byzantine and Eastern churches.) -

Dimitri Obolensky : Byzantium and the Slavs. 1994, ISBN 0-88141-008-X .

(Study of the Byzantine heritage among the Slavic peoples.) - Basil Tatakis, Nicholas J. Moutafakis: Byzantine philosophy. Hackett, Indianapolis / In. 2003, ISBN 0-87220-563-0 .

Web links

- Brief overview of sources by Prof. Halsall

- Scientific portal for Byzantine history (English)

- Link list to the Byzantine Empire (English)

- E-texts at Dumbarton Oaks, one of the most important institutions for the study of Byzantium

- Glossary (Prosopography of the Byzantine World)

- Sources in engl. Translation ( Memento of April 13, 2001 in the Internet Archive )

- Website of the Institute for Byzantine and Neo-Greek Studies at the University of Vienna with links to other research institutions, projects and information on various aspects of Byzantium

- Website of the Institute for Byzantine Research of the Austrian Academy of Sciences with further resources and a repository with scientific articles on various aspects of Byzantine history

- A. Vasiliev, A History of the Byzantine Empire

Remarks

- ^ Georg Ostrogorsky: History of the Byzantine State ( Handbook of Ancient Science XII 1.2). Third edition. Munich 1963, p. 22.

- ↑ So recently z. B. Peter Schreiner : Byzantium. 3. Edition. Munich 2008. Schreiner suggests speaking of “Byzantine” only after the death of Justinian (I) (565): early Byzantine from the late sixth century to the ninth century, middle Byzantine from the ninth century to 1204 and late Byzantine to 1453. The 2008 published Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire treated the sixth to the 15th century, and John F. Haldon , a leading international expert, sees the decisive turning until the seventh century, with the end of late antiquity: John Haldon: Byzantium in the seventh century . The transformation of a culture. Second edition. Cambridge 1997. On the discussion, cf. also Mischa Meier : Ostrom - Byzanz, Spätantike - Mittelalter. Reflections on the “end” of antiquity in the east of the Roman Empire. In: Millennium 9 (2012), pp. 187-254.

- ↑ See the two reviews of the 3rd edition of Peter Schreiner's handbook / introduction by Günter Prinzing , in: Südost-Forschungen 65/66 (2006/2007), pp. 602–606 and Ralph-Johannes Lilie, in: Byzantinische Zeitschrift 101 (2009), pp. 851-853.

- ↑ See Mischa Meier: Ostrom - Byzanz, Spätantike - Mittelalter. Reflections on the “end” of antiquity in the east of the Roman Empire. In: Millennium 9 (2012), pp. 187-254.

- ↑ For Westrom see Henning Börm : Westrom. From Honorius to Justinian. 2nd edition, Stuttgart 2018. For general information on the migration period, see especially Mischa Meier: History of migration. Europe, Asia and Africa from the 3rd to the 8th centuries. Munich 2019.

- ^ Brian Croke: Dynasty and Ethnicity. Emperor Leo I and the Eclipse of Aspar. In: Chiron 35, 2005, pp. 147-203.