Republic of Venice

| Serenìsima Repùblica de Venessia (Venetian) Respublica Veneta (Latin) |

|||||

| Republic of Venice | |||||

| 697-1797 | |||||

|

|||||

| Official language | Venetian and Latin | ||||

| Capital | Venice | ||||

| Form of government | Aristocratic Republic | ||||

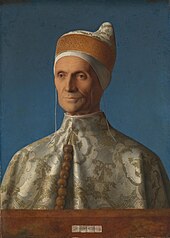

| Head of state , also head of government | Doge | ||||

| The Republic of Venice around 1500 including brief possessions, plus the main trade routes | |||||

The Republic of Venice ( Venetic Republica de Venessia or Serenisima Republica ; Italian Serenissima Repubblica di San Marco , Serene Republic of Saint Mark ') after the symbol of the city, the St. Mark's lion , also known as Mark's or lion's Republic referred, was on 7/8 . Century until 1797 a maritime and economic power , the center of which was in the northwest of the Adriatic . Their supremacy culminated in a colonial empire that stretched from Northern Italy to Crete and at times to Crimea and Cyprus , and was directed from Venice . In addition, Venice had merchant colonies in Flanders and the Maghreb , in Alexandria and Acre , in Constantinople and Trebizond and in numerous cities on the Adriatic.

A trading and sea power

The wealth of the aristocratic republic resulted from the fact that it acted as a hub between the Byzantine Empire and the Holy Roman Empire and at the same time monopolized important goods. The fragmentation of Italy was also beneficial to them. Only the nobility exercised the profitable long-distance trade ( Levant ) and increasingly controlled the political leadership - up to the abolition of the popular assembly.

Mainly legends and only a few historically reliable sources report about the early days. It was not until the 13th century that there was a broad written tradition, but the extent of this can then be compared with that of Rome . To legends , the state-controlled history has contributed significantly. She often projected the peculiarities of Venetian society, perceived as groundbreaking, back into the past. In doing so, she concealed or reinterpreted much of what contradicted the ideals of unity, justice and balance of power.

The sea power succeeded in playing a major role in the politics of the Mediterranean , despite limited resources and a scattered dominion area . Almost from the start, Venice navigated between the great powers such as Byzantium and the Holy Roman Empire or the papal power, rigorously used the power of its war fleet and its superior diplomacy , and set up trade blockades and professional armies. It had the competition of Italian trading cities such as Amalfi , Pisa , Bologna , and especially Genoa to defend. Only the large territorial states like the Ottoman Empire and Spain pushed back the influence of Venice militarily, the emerging trading nations like the United Netherlands , Portugal and Great Britain economically. France occupied the city in 1797; shortly before that, on May 12, the Grand Council voted for the dissolution of the republic.

Origin and rise

Settlement of the lagoon

The starting point for the settlement of Venice was a group of islands in the vicinity and in the lagoon , which pushed the deposits of the Brenta and other small rivers further and further into the Adriatic. The Grand Canal is the extension of the northern arm of the Brenta . The population of the fishing settlements on and in the resulting lagoon, which date back to Etruscan times, increased as a result of refugees who, according to legend, came to safety in 408 from the Visigoths of Alaric , but especially 452 from the troops of the Hun Attila . When the Lombards invaded northern Italy in 568 , another stream of refugees reached the lagoon. Venice's legendary founding date, March 25, 421, could be a reminder of the early immigrants.

In addition to the island of Rialto, the city was built by the neighboring Luprio, Canaleclo, Gemine, Mendicola, Ombriola, Olivolo and Spinalunga. Dense post gratings made of tree trunks were driven into the ground to expand the settlements. The fleet also devoured large quantities of wood.

Byzantine rule

With the conquest of the Ostrogoth Empire under Emperor Justinian I ( Restauratio imperii approx. 535 to 562), the lagoon came under Eastern Roman-Byzantine rule. However, the conquest of large parts of Italy by the Lombards from 569 forced Emperor Maurikios to grant the remaining peripheral provinces greater independence, and so the Exarchate of Ravenna was created at the end of the 6th century . The Exarch appointed the Magister militum as the military and civil commander in chief of the province. Tribunes were subordinate to him in the lagoon . The provincial capital was initially Oderzo , but it was conquered by the Lombards in 639 and destroyed in 666. The province largely dissolved and the lagoon was increasingly on its own. The bishopric was moved from Altinum to the safer Torcello in 635 . Nonetheless, trade with the mainland, especially in salt and grain, played an important role as early as the 6th century, which apparently increased in the 8th century. In contrast to their peers outside of Venice, the Venetian aristocracy, most of whom traced back to Roman roots, acquired their fortunes around 800, not only from immobile property, but increasingly through trade.

According to tradition, Paulicius was raised to the rank of first doge in 697 . Around 713/16 a Dux (leader or duke) Ursus is mentioned for the first time as the deputy of the exarch. The relocation of his official seat took place under his successors first to Heraclea and later to Alt Malamocco . 811 became the official seat of the Doge Agnello Particiaco Rialto .

According to the Venetian tradition, when the first doge is chosen, the so-called twelve “apostolic” families of Badoer, Barozzi, Contarini , Dandolo , Falier, Gradenigo , Memmo, Michiel, Morosini, Polani, Sanudo and Tiepolo appear for the first time .

Increasingly independent of Byzantium, Venice showed itself for the first time in the beginning Byzantine iconoclasm (726/27), when the city sided with the papal. In addition, for the first time there was a contract with the Lombards on their own authority, that is, without Byzantine confirmation. In this context, the Doge is said to have received the nickname "Ipato" (Greek "Hypatos"), ie "Consul", but not, as is often assumed, in recognition of his services in the reconquest of Ravenna and the Pentapolis after 729. The reconquest probably took place in 739/740. As early as 732, the places in the lagoon were placed under their own bishop, which will have strengthened their togetherness and at the same time made them more clearly visible.

Between Byzantium, the Lombards and the Frankish Empire

With the second conquest of Ravenna by the Lombards (751), Byzantine rule in northern Italy ended. Nevertheless, Venice appreciated the continued formal dependence on Byzantium, because only this enabled it to maintain its independence: initially from the Lombards, but even more so from the Franks (the Frankish King Charlemagne conquered the Lombard Empire in 774) . His son, King Pippin of Italy , made several attempts to conquer Venice between 803 and 810, and a siege of the city was ultimately unsuccessful. In the Peace of Aachen in 812 Venice was finally recognized as part of the Byzantine Empire. This and the relocation of the Doge's seat to the place of today 's Doge's Palace formed the basis for the later special development of the city compared to the rest of Italy.

There was by no means unanimity within the lagoon during this process. The fourth Doge Diodato , son of the probably first Doge Orso, apparently fell victim to the fighting between the prolangobard and probyzantine factions in 756. The probyzantine successor Galla , who had overthrown him, was also assassinated after a few months. Domenico Monegario, on the other hand, led a prolangobard faction until his fall in 764, which benefited Venice's northern Italian trade. At the same time, the first attempts were made to limit the Doge's power through two tribunes. Maurizio Galbaio , who held the Doge's office from 764 to 787, tried against strong opposition to enforce a Doge dynasty by making his son Giovanni his successor. But the latter fell out with the city's clergy and was ultimately defeated by a Pro-Frankish faction under the leadership of Obelerio , who then had to flee with his family in 804 before the siege by King Pippin , a son of Charlemagne, with his family.

Under the Particiaco dynasty, the city made significant progress. Her self-confidence grew, but what was missing was a spiritual elevation, a symbol of the city's importance.

After St Mark's relics were stolen from Alexandria (828), where there was already a Venetian merchant colony, the evangelist Mark became the city's patron saint . The republic was consecrated to him and the symbol of the evangelist, the winged lion , became the emblem of the republic. You can still find it today in the entire area of former Venetian possessions. This was a further step towards independence, now against the Patriarch of Aquileia , who claimed spiritual supremacy and thus demanded access to Venetian bishoprics. Venice's claim was symbolized by the transfer of the relics of the evangelist Mark to Venice. As the guardian of this high-ranking relic, Venice was able to underline its spiritual position and independence from the Patriarch of Aquileia by the fact that the saint , to whom the founding of the patriarchate was ascribed, was "physically" present in Venice.

But the political failures of Doge Iohannes Particiaco , who had to flee Venice in 829 and seek refuge with the Frankish Emperor Lothar while the Byzantine tribune Caroso ruled the lagoon for six months, contrasted sharply with this symbolic success. The Doge could only return with the help of the Franks. He had Caroso blinded and banished because, as a senator from Constantinople, he was not allowed to be executed. At the same time, the Byzantine office of tribune was soon to disappear. But as early as 832, John was banished to a monastery.

"Venetia" was now understood to mean an area that reached from Grado to Chioggia . In the Pactum Lotharii , in which Emperor Lothar I endowed Venice with numerous rights (840), 18 different places are listed, including Rialto and Olivolo. Their independence was finally recognized. Under the Doge Tribunus Memus , these two places were included in a common defense system, from which the actual city of Venice emerged. The trigger for this effort were attacks by the Hungarians who penetrated the lagoon in 900. A group of wealthy merchants established themselves within the city, most of whom came from the noble families. In contrast to their peers on the mainland, trade was highly regarded by them.

The Doge dynasty of the Particiaco

The weakness of the Byzantine Empire caused Venice to interfere in the raids and conquests initiated by Slavs , Hungarians and Muslims ( Saracens ). As early as 827/828, at the request of the emperor, Venice sent a fleet against the Saracens who had begun to conquer Sicily . At the same time, Venice fought pirate fleets of the Narentans (in the south of today's Croatia), to which the Doge Pietro Candiano fell victim in 887. Around 846 the Slavs advanced as far as Caorle , in 875 the Saracens as far as Grado - they had already attacked the Venetians in the sea battle off the island of Sansego ( Susak , southeast of Pola ).

Around 880, however, Venice succeeded in expanding its position as a regional supreme power, a development that could not stop the advance of the Hungarians (900) who destroyed Altino. In 854 and 946 Comacchio , which ruled the mouth of the Po , was conquered and destroyed by the Venetians. However, for Venice came to the Papal States in conflict, because this was by Pippi niche donation made of 754 overlord of Comacchio. The conquerors were first hit by the papal excommunication .

Meanwhile, the relationship with Byzantium increasingly assumed the character of an alliance. This phase of Venetian history was dominated by the Particiaco dynasty (810 to 887, again 911 to 942), although the rule of Pietro Tradonico , which was extremely successful, interrupted the dominance of the Particiaco from 837 to 864. At the same time, there were several treaties with the kings of Italy, such as 888 with Berengar I , 891 with Wido , 924 with Rudolf of Burgundy and 927 with Hugo I.

The Dogian dynasty of the Candiano, imperial policy of the Ottonians

Even under Pietro II Candiano (932–939) Venice asserted its supremacy over Capodistria ( Koper ), one of the most important trading places in Istria . For the first time, a blockade was sufficient, a means of power that Venice successfully used in the countries bordering the Adriatic for centuries. The Candiano family had already played an important role earlier and in 887 provided Pietro I. Candiano, their first doge. However, after barely half a year he died fighting the Narentans .

Under the Candiano dynasty, who were the Doges without interruption between 942 and 976, it almost seemed as if Western European feudal vassal relationships could gain the upper hand. Here had Pietro III. Candiano (942–959) gave way to his son Pietro IV , who was supported by the feudal lords of the mainland and King Berengar II . This in turn leaned on Otto I , who was made emperor in 962, and who induced the Doge to pay him tribute - in exchange for access to the church property in his area.

Otto II's imperial policy towards Venice fundamentally broke with the tradition of his father Otto I, which had existed since 812. As a result, the pro-Ottonian Candiano dynasty was overthrown in 976. The Doge and his son Vitale, Bishop of Venice, were killed and the Doge's Palace burned down. The new doge left her inheritance to the widow of his murdered predecessor, Waldrada, because she was under the protection of the imperial widow Adelheid .

When the Coloprini family, still loyal to Otto II, came into open conflict with the pro-Byzantine Morosini and Orseolo, they turned to Emperor Otto. While the first trade blockade ordered in January or February 981 hardly affected Venice, the second trade block imposed in July 983 caused considerable damage to the city. The Coloprini who remained in Venice were now imprisoned, their city palaces destroyed, and a few years later the Coloprini who had returned were also killed by the Morosini. Only the early death of Otto II (late 983) possibly prevented the submission of Venice to the empire.

The Orseolo, ascent to a great power

With the reign of Doge Pietro II. Orseolo (991-1008) the rise of Venice to a great power began, both economically and politically. In 992, Venice received a privilege from Emperor Basil II , which significantly reduced the trade taxes in Byzantium and favored the Venetians over the rival cities. At the same time, the privilege called the Venetians extraneity , i.e. foreigners , which was certainly no longer a term for Byzantine subjects, no longer even according to the claim.

The establishment of free navigation through the Adriatic was just as trend-setting. From 997 to 998 the first campaign against the Narentani pirates of Dalmatia was successful, and by 1000 the islands of Curzola and Lastovo , which were considered hiding places for pirates, were conquered. Important successes were also achieved further south of the Adriatic. 1002-1003 the fleet was able to defeat the Saracen besiegers off the Byzantine Bari .

Pietro is credited with the ceremony of the annual marriage of Venice to the sea ( Festa della Sensa ). This state spectacle symbolically underscored Venice's claim to control the Adriatic, if not the entire Mediterranean. The faction of groups focused on the Adriatic and long-distance trade had finally prevailed. The Doge now claimed the title of Dux Veneticorum et Dalmaticorum .

Political institutions, internal balance of power, isolation of the ruling class

This long phase, in which powerful families and their clientele fought bloody battles for Doge power and tried to found a dynasty, and in which foreign powers in particular repeatedly tipped the scales , left deep traces in Venetian historiography - but above all it has initiated political reforms. These were aimed at making the powerful Doge into a figurehead who was subject to close control and supervision without completely losing political influence.

Venice class system corresponded to the high and late Middle Ages to the division of labor. The Nobilhòmini were responsible for politics and high administration as well as for the war and naval leadership. Their economic basis, however, was just as much long-distance trade as with the Cittadini , those merchants whose families had no access to the politically decisive institutions of Venice. Nobilhòmini and Cittadini provided funds and added value through trade and production, the Populani , the majority of the population, provided soldiers, sailors, craftsmen, servants, did manual labor and carried out retail trade.

The early institutions arose in a society that relatively seldom needed and kept written documents. This is how the Small Council came into being as an advisory body for the Doge and the Arengo , a kind of people's assembly which in the early days probably still had participation rights, but which soon became a mere acclamation organ . As the Arengo lost its importance, the influence of the Small Council, whose six members represented the sixths of the city ( sestieri ) that made up Venice , grew .

Extensive written evidence in the form of council minutes and guarantees existed as early as the early 13th century. The documentation of the constitutional development as well as the domestic and foreign policy of Venice is from then on extensive, with few gaps and in its density can only be compared with that of the Vatican .

This was in close interaction with the institutions, which were constantly changing and developing. The principle of careful balancing of power and mutual control of the various bodies was always observed; this principle was one of the reasons for the unique stability of this state in troubled Europe. The aim of all reforms was to prevent the domination of a single family, as was common in the city-states of northern Italy and with which Venice itself had had such bad experiences. The downside, however, was a strict police and informal system.

Between 1132 and 1148 the sole rule of the Doge was opposed to a body from which the Grand Council developed. Representatives of the most important families had a seat and vote. Around 1200 with little more than 40 members, it grew temporarily to over 2,000 members. In 1297 the so-called closure of the Great Council ( Serrata ) took place, but this was a long process that dragged on into the 14th century. This limited access to the Grand Council with the right to actively and passively elect the Doge and all leadership positions to the families who were able to advise them. "Life-long hereditary membership in this council gave all members of the ruling class the security that they would not suddenly find themselves excluded." On September 16, 1323 it was clarified that the grand council was admitted whose father or grandfather had sat on the grand council . In 1350 the Badoer, Baseggio, Contarini , Cornaro , Dandolo , Falier (o), Giustiniani, Gradenigo with their branch line Dolfin , Morosini, Michiel (according to tradition a branch of the Frangipani ), Polani and Sanudo were among the twelve large families . They were followed in rank by the other twelve families Barozzi, Belno, Bembo, Gauli, Memmo, Querini , Soranzo, Tiepolo, Zane, Zen, Ziani and Zorzi. (The Bragadin later followed the Voucherno and the Ziani the Salamon.) In the rank after these came 116 advisable families, called curti or Case Nuove (among them such well-known as Barbarigo , Barbaro , Foscari , Grimani , Loredan , Mocenigo , Pisani, Polo, Tron, Vendramin or Venier ) and 13 families who had immigrated from Constantinople. Later on, several other local and immigrant families were co-opted. In the 15th century, the patriciate was awarded on an honorary basis to around 15 "foreign" noble families who had rendered outstanding services to the Serenissima primarily through military support .

On August 31, 1506, the entry of the children of families eligible for advice was regulated in a birth register ( Libro d'oro di nascita ) and since April 26, 1526 there has been the Libro d'oro dei matrimonio , in which the marriages of the Nobilhòmini were entered . Only those who were entered in these lists, later called the Golden Book , and who were re-registered when they reached the age of majority, belonged to the Great Rate ( maggior consiglio ) for life. The Grand Council was not actually a legislature , but it had to be heard on all bills. At the same time, all political offices were filled here, so that he was occasionally referred to as the "election machine".

A kind of presidium of the Grand Council was the Signoria , the highest controlling body. In addition to the Doge and the Small Council, the heads of the Quarantia , the presidents of the Supreme Court, were represented. In the middle of the 13th century, the Senate emerged from the Great Council, which was originally a council made up of veteran traders and diplomats that dealt with trade and shipping issues. Since all other political questions revolved around these questions in Venice, the senators, initially known as pregati , gradually took on various tasks and thus formed a kind of government. Conversely, this caused all long-distance trading families to concentrate their influence here, where all economic questions were negotiated and decided.

In addition, from 1310 there was the Council of Ten , a supervisory body in which, as in almost all important bodies, the doge also had a seat and vote. The Council of Ten was created after a nobility revolt to prevent further unrest. It was a kind of supreme police and administrative body that was endowed with extensive rights. It is characteristic of Venice that this body of public control and surveillance sometimes competed fiercely with the Senate, especially in times of crisis.

One of the highest offices after the Doge was that of the procurators , also elected for life , who represented a kind of finance and treasury ministry. They resided in the proxy offices on St. Mark's Square .

In addition to these main committees, special committees were set up for every major issue, dealing with the settler uprising in Crete , cleaning the canals and water management regulation in the lagoon, with public customs and fashion, etc. All offices - except that of the Doge, the Procurators and the Chancellor - were only filled for a short time, for a maximum of one or two years. Often the responsibilities and tasks of different committees overlap, which also served as mutual control. In the event of misconduct in office, advocators investigate and, if necessary, bring charges against those responsible. There was no proper vocational training until the end of the republic, so that all positions were filled by more or less experienced lay people.

In the Doge's Palace, the Chancellor, the only one not held by a Nobilhòmine for life , directed the correspondence. He was the only one whose qualifications were subject to verifiable criteria, while all others only had to be assessed and selected as suitable. Other subordinate administrative posts were also filled with Cittadini , whereby only those who, as well as their father and grandfather, were born from legal marriage in Venice and entered in the so-called "Silver Book" came into question.

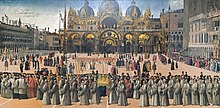

The political leadership, including the financial organs, concentrated around St. Mark's Square, while the island of Rialto formed the economic center.

Great power and decline

Supreme power in the Adriatic Sea, trading hub between East and West

In addition to the conflicts with the Holy Roman Empire , especially with the Patriarch of Aquileia , the Normans of southern Italy in particular threatened Venice's position of power in the Adriatic. At the same time, Hungarians and Croatians pushed their way to the Adriatic coast. When the Dalmatian cities asked the Normans for help against the Croats in 1075 and the Norman leader Robert Guiscard already established a foothold in Albania on a conquest of Constantinople , Venice's trade routes through the Adriatic were threatened with being blocked. This fear was not to let go of the city and prompted it to prevent the rule of a single political power over both Adriatic shores by all means. Only in this way could Venice's livelihood, long-distance trade, be secured.

Venice had been granted privileges before, but its trading supremacy rested mainly on two privileges. The city achieved this by supporting Henry IV in the investiture dispute with Pope Gregory VII . On the other hand, she assisted Emperor Alexios I of Byzantium against the Turkish Seljuks and the Normans of southern Italy, who threatened Constantinople from east and west at the same time. Due to the privilege of Henry IV, the merchants of the Holy Roman Empire were forbidden to bring their goods beyond Venice to the east. Conversely, Greek, Syrian or Egyptian traders were not allowed to offer their goods in the empire. Venice acted as a broker between the two empires, a function that was expressed through trading houses for the different trading nations, whose fees and tariffs brought large amounts of gold and silver into the city.

Nonetheless, the relationship with its old ally, the Byzantine Empire, soon turned out to be particularly conflictual . After the Battle of Manzikert (1071), the empire was increasingly on the defensive against the Turkish Seljuks. Venice offered Emperor Alexios I the support of his fleet in the fight against the Turks and the Normans and received trade privileges for this, which exempted its traders from all taxes from 1082 onwards. In addition, there was a large traders' quarter on the Golden Horn . This enabled the Venetians to dominate the Byzantine Empire economically within a few decades. This supremacy went so far that the economic foundation of the Byzantine state was threatened. The Oriental Schism (1054) and the First Crusade from 1096 to 1099 further contributed to the estrangement between Venice and Byzantium.

But the Crusades opened up new opportunities for Italian trading cities. In order to intervene here, in 1099, after having stayed away from the Crusade for a long time, Venice sent 207 ships under the command of the son of the Doge Giovanni Vitale and the Bishop of Olivolo. In December there was a sea battle off Rhodes with competitors from Pisa, after whose defeat the Venetians took relics of St. Nicholas with them from Myra . Venice was granted tax exemption and colonies in all cities still to be conquered in the emerging Kingdom of Jerusalem .

Conflict with Hungary, Friedrich Barbarossa and the Peace of Venice

With the Kingdom of Croatia, which belonged in personal union to the Kingdom of Hungary and was supported by the Pope, there have been repeated conflicts over the cities of Istria and Croatia and the bishopric of Grado since the early 10th century. The opponents of Venice allied themselves with the Normans and took the son of Doge Domenico Silvo (1070-1084) prisoner in a sea battle off Corfu . The opposition of the Normans was based on the fact that they were trying to conquer the Byzantine Empire while the Doge, who was married to a daughter of the emperor, pursued commercial interests there. Emperor Alexios I gave the Doge the title Duke of Dalmatia and Croatia . At the same time, however, Ladislaus installed a nephew as king in Dalmatia and Croatia. From 1105 to 1115 the conflict escalated into a war in the course of which Venice was able to recapture some coastal towns. Split fell in 1125 .

In 1133–1135, the Croats conquered Šibenik , Trogir and Split. At the same time, Padua tried to shake off the Venetian salt monopoly and Ancona tried to challenge Venice for supremacy in the Adriatic. Pope Eugene III. excommunicated Venice and its Doge. In internal power struggles, the powerful Badoer and Dandolo were temporarily ousted. The situation became particularly dangerous when a marriage alliance between Hungary and Byzantium emerged.

The field of conflict was widened by the fact that Friedrich Barbarossa got involved in Italian politics. Venice joined forces in 1167 with the Lega Lombarda , a northern Italian city federation supported by the Pope (see Ghibellines and Guelphs ). Even with the Normans of southern Italy, Venice was now in league, because, another constant of Venetian policy, the city had no interest in an overpowering neighbor on the mainland. In 1177, Frederick I and Pope Alexander III agreed . a peace treaty in Venice.

Under Emperor Manuel I (1143-1180), whose mother came from Hungary, Byzantium succeeded submission significant parts of today Serbia belonging Raszien . In 1167, the Hungarians were subject to him, making Byzantium once again the immediate neighbor of Venice.

Open conflict with Byzantium, Fourth Crusade

Relations with Byzantium had been extremely tense for decades. Since the privilege of 1082, Venice increasingly insisted on a monopoly-like position in Constantinople. This led to serious conflicts, especially with Pisa, which increased in the course of the wars for the Holy Land . The Doge Domenico Michiel drove with 40 galleys , 40 cargo ships and another 28 ships to Jerusalem in April 1123 in support of Baldwin II , proposed an Egyptian fleet in front of Ashkelon and on July 7th 1124 Tire fell . Although the doge refused the royal crown of Jerusalem, he drove his fleet against Byzantium when he heard of the privilege of the Pisans by Emperor John . The fleet plundered Rhodes , Samos , Chios , Lesbos , Andros , Modon and Kephallenia . In 1126, the emperor renewed the trading privilege of 1082.

Emperor Manuel I (1143–1180), the son and successor of John, not only pursued a restoration policy in Asia Minor and Italy ( Ancona was a Byzantine bridgehead for almost two decades), but also a rapprochement with Hungary. Both goals of Byzantine politics were directed against the interests of Venice, since if they had been realized, Constantinople would have extended its sphere of power to Istria and, with the control of the Adriatic, would have gained power over Venice's sea routes.

Emperor Manuel also wanted to revoke the 1082 agreement. On March 12, 1171, in an apparently completely surprising operation, he confiscated all Venetian property and in one night imprisoned the Venetians throughout his sphere of influence. A Venetian fleet carried out a campaign of revenge, but had to withdraw without having achieved anything. In Venice this led to riots in the course of which the doge was murdered on the street. The Latin pogroms of 1182 under Manuel's successor Alexios II Komnenos claimed even more victims . However, the rival Italian cities were more affected by this than Venice, whose merchants regained access to the Byzantine market in 1185, albeit under significantly stronger restrictions than before 1171. With a victory over the Pisan fleet in 1196, Venice was able to reassert its trade monopoly in the Adriatic. Alexios III Venice issued a far-reaching trade privilege in 1198.

The catastrophe of 1171 apparently led to the overcoming of social tensions and contradictions within the ruling class. The six city quarters (sestieri) were created, each represented by a representative in the Small Council, control and management organizations for trade and production were set up, the food market strictly regulated, and war-economy efforts were made. In addition, all wealthy people were subjected to a rigorous lending system in which large amounts of money could be raised at short notice against interest to pay for wars, but also to secure the supply of the city with food.

The Doge Enrico Dandolo used the Fourth Crusade (1201–1204) to conquer the still rich metropolis of Constantinople on the Bosporus - by far the largest city in Europe - and probably for revenge, as he himself had been a victim of the anti-Venetian actions of Emperor Manuel. It helped him that the Byzantine Empire began to disintegrate, because Trebizond , Lesser Armenia , Cyprus and parts of central Greece around Corinth had already renounced the capital. The lack of money crusader army that gathered near Venice from 1201 accepted Dandolo's proposal to recapture the stubborn Zara ( Zadar ) for Venice - to compensate for the crossing to the Holy Land or to Egypt on Venetian ships. After the conquest, the flight of a Byzantine pretender to the throne gave Dandolo the pretext to march in front of Constantinople. After two sieges, one of the greatest pillages of the Middle Ages took place. It brought immense treasures to the south and west of Europe. In Venice, the quadriga on St. Mark's Church was a symbol of Dandolo's triumph. Numerous Venetians set out to secure a piece of the crumbling Byzantium for themselves. The main territorial booty for Venice was the island of Crete .

Only a relatively small part of the Byzantine Empire fell to the conquerors, while partial empires formed in Asia Minor and Greece (e.g. the despotate of Epirus ), which in the following decades increasingly oppressed the Latin Empire , which was founded with significant participation from Venice ; the empire of Nikaia finally succeeded in retaking Constantinople in 1261 . However, these struggles not only overwhelmed the resources of the Greek sub-empires, but also relieved the Turkish Emirates, which were able to stabilize their settlement and power structures. The Beys of Aydın and Mentesche converted their coastal dominions into sea powers and thus became a serious danger. On the other hand, Venice established a consul there, maintained trade contacts and used Turkish mercenaries to keep its colonial empire together.

Colonial empire, competition from Genoa, attempts to overthrow

Venice benefited for almost half a century from the establishment of the Latin Empire , which it effectively controlled. The contractual agreements expressly guaranteed the Serenissima rule over three eighths of the empire, a rule that Venice only exercised in accordance with its commercial interests - and its limited military capabilities. As a result, it established a colonial empire in the Aegean Sea with a focus on Crete in the following years . A chain of fortresses stretched from the east coast of the Adriatic via Crete and Constantinople to the Black Sea (see Venetian colonies ). Under the protection of the Mongol Empire, it soon opened up trade deep into Asia. The most famous of these travelers is probably Marco Polo .

But this supremacy was not without risk. The most powerful rival was first Pisa , then Genoa. The Genoese had long tried to prevent the conquest of Crete and temporarily occupied the island themselves. In addition, the Byzantine exile pretender in Nikaia, Asia Minor, allied with Genoa. In 1261 the allies surprisingly succeeded in retaking Constantinople. Venice had to cede part of its territory and its privileges to its arch-rival Genoa. This permanent conflict between the two northern Italian trading metropolises escalated into four wars lasting several years in the 13th and 14th centuries. In 1379 the Genoese managed to conquer Chioggia for a year in alliance with Hungary .

At the same time, Venice tried to assert itself in the disputes between the Staufers, above all Friedrich II. , And the Pope. Finally Charles of Anjou succeeded in breaking the power of the Hohenstaufen in southern Italy (1266, finally 1268). Since Charles continued the policy of the Normans and tried to conquer Byzantium, he was the given ally of Venice to regain his privileges there. But in 1282 the Sicilian Vespers put an end to the joint plans and Sicily fell to the Iberian Kingdom of Aragón . It took another three years before Venice was re-admitted to Constantinople, but under unfavorable conditions. In addition, it came into conflict with Charles's successors, who managed to acquire the royal crown in Hungary. There was again the danger of the Adriatic being sealed off and Venice lost its dominance in Dalmatia.

A further development put the rule of Venice in danger, the emergence of the signories such as that of the Scaligeri in Verona or the Este in Ferrara . After Venice had increasingly succeeded in playing off the neighboring mainland cities against one another, subordinating them to its interests through trade blockades, coups or military force - these cities included Ferrara, Padua , Treviso, Ancona and Bologna - the Signori threatened its supremacy. This form of rule in the cities of northern Italy soon brought several of these rapidly growing centers into one hand, which made Venice politically open to blackmail. Venice was particularly threatened by Milan and Verona.

Nevertheless, Venice managed to maintain its dominant position in the eastern Mediterranean, although more than half of the population was killed in the first plague wave of 1348 and although in 1379 the Genoese in league with Hungary almost conquered the city. In addition, in 1310 a noble rebellion under the leadership of Baiamonte Tiepolo shook the republic, in 1355 the Doge Marino Falier attempted a coup and in 1363 the Venetian settlers on Crete rose up against the rigid politics of Venice in a year-long uprising .

Prosperity, expansion in Italy, Ottoman Empire

The Peace of Turin (1381) heralded a new phase of prosperity, especially since Genoa, weakened by internal struggles, no longer represented a great danger. After long battles with Hungary, who threatened the bases in Dalmatia, the Venetians even managed to conquer all of Dalmatia between 1410 and 1420. But they did not succeed in expanding their old dominion in southern Istria to the north; the northern part came under the influence of the Habsburgs . The demarcation was established around 1500, when the county of Gorizia fell to Habsburg by inheritance and Trieste was withdrawn from Venetian influence. In contrast, Corfu was bought by Venice in 1386 , as well as the Ionian Islands and a number of cities along the Albanian coast.

Meanwhile, the Turks succeeded - first under various dynasties, then under the leadership of the Ottomans - to conquer Asia Minor. In the mid-14th century they crossed over to Europe and increasingly reduced Byzantium to its capital, making them rivals to Venice. Because despite the reconquest of 1261, the passage through the Bosporus , which Constantinople protected, was of the greatest importance for Venice. All the more so when the last trading post in the Holy Land fell in 1291 . As a result, Venice had to concentrate on the trade routes via Lesser Armenia and Tabriz as well as via Famagusta , Constantinople and the Black Sea. This in turn exacerbated the rivalry with Genoa, which - even in times of relative peace - repeatedly led to raids on enemy bases and open piracy. Around the same time, Venice began to expand to the mainland, the Terra Ferma , where the nobility already owned extensive estates and where Venetians were often employed in the post of Podestà . The policy of conquest that began in 1402 was highly controversial in Venice because it inevitably led to conflicts with the empire, the Pope and the most powerful states in Italy. The attacks on Ferrara , which Venice was the first mainland city to conquer in 1240, had failed, as had been the case in the war from 1308 to 1312. In both cases, Venice failed primarily because of papal resistance. In 1339, however, Treviso was conquered in the course of a war against the Scaliger of Verona , although this conquest was not finally completed until 1388. In the years after 1402, the year of death of the Milanese Gian Galeazzo Visconti , who had ruled large parts of northern Italy, Venice took control of the whole of Veneto and Friuli , as well as the Dalmatian coast.

With these conquests Venice challenged the King of Hungary and the Holy Roman Empire Sigismund , whose rights were thereby violated in both cases. After all, the threatened Aquileia was an imperial fief and, as King of Hungary, Sigismund had a claim to the coastal cities of Dalmatia since the Treaty of Turin (1381). A first war broke out between 1411 and 1413, but despite blockade measures it did not lead to any results. 1418-1420 there was a second war between Venice and the king, at the end of which Feltre , Belluno , Udine and the rest of Friuli fell to Venice.

This conquest was accelerated under the leadership of Doge Francesco Foscari (1423-1457). In 1425 a Venetian army defeated the Milanese at Maclodio (in the province of Brescia ) and advanced the border to the Adda . But in 1446 Milan, Florence, Bologna and Cremona allied against Venice. Venice triumphed again at Casalmaggiore , and the Visconti were overthrown in Milan . Venice allied itself temporarily with the new lord of Milan, Francesco Sforza , but switched back to its enemies in view of its increasing power.

It was not until the Peace of Lodi in 1454 that a provisional border was drawn: The Adda was established as the Venetian western border. These conquests and several attempts to conquer Ferrara , to which the Papal States claimed, led the Papal States and most of the other Italian states to see Venice as their fiercest rival.

Venice had an advantage as the central financial center in these protracted wars, because it could more easily pay the large sums of money devouring professional armies of the Condottieri who were now waging the wars in Italy. But his opponents tried various monetary and economic policy measures to shake this position. The means ranged from the trade blockade to the issue of forged coins (see economic history of the Republic of Venice ).

Many of these means were not available to the Ottomans, who had become a great power with the first siege of Constantinople (1422) at the latest, which was now about to conquer the numerous small domains. Venice defended Thessaloniki in vain from 1423 to 1430 . The Hungarians were also repulsed. In 1453 the Ottomans finally succeeded in conquering Constantinople . Suddenly the still important trade with the Aegean and Black Sea regions broke off. Nevertheless, the Venetian diplomacy succeeded in tying new threads, so that the quarter in the now Ottoman capital could be occupied again. In 1460 Ottoman troops conquered the last significant Byzantine bastion Mistra , making the Ottoman Empire the immediate neighbors of the Venetian fortresses Koron and Modon on the Peloponnese . In 1475 the Crimea was added, causing the Genoese-mediated trade to collapse. Even in the time before the conquest of Constantinople, a wave of Greek refugees started to the west, so that the Greeks became the largest community in Venice. Its approximately 10,000 members were given the right to build an Orthodox church in 1514, San Giorgio dei Greci . The number of Armenians who consecrated their church of Santa Croce in 1496 also increased. There were also Jewish refugees from Spain, from where they were expelled in 1492.

1463–1479 Venice was again at war with the Turkish great power. Despite isolated Venetian successes, the Ottomans conquered the island of Negroponte in 1470 . Even attempts to form alliances with the Shah of Persia and attacks on Smyrna , Halicarnassus and Antalya did not produce any tangible results. When the rulers of Persia and Karaman were defeated by the Ottomans and Skanderbeg , who had defended Albania, died, Venice carried on the war alone. While there could Scutari initially defend against the besiegers, the city lost two years later still. The Hohe Pforte even attempted an attack in Friuli and Apulia . It was not until January 24, 1479 that a peace agreement was reached, which was confirmed five years later. Venice had to forego the Argolis , Negroponte, Skutari and Lemnos and, moreover, pay tribute 10,000 gold ducats every year .

Venice seemed all the more concentrated on the Italian mainland. Against the resistance of Milan, Florence and Naples it tried to conquer Ferrara in league with the Pope. Despite heavy defeats on land, it was possible to conquer Gallipoli in Apulia. In addition, in the peace of 1484 Venice fell to the Polesine and Rovigo . In the battles against the French King Charles VIII , who tried to conquer Italy in 1494, and in connection with the Spanish conquest of the Kingdom of Naples, the Venetian fleet occupied a large part of the Apulian coastal cities.

Overall, Venice had largely lost its supremacy in the east, but still benefited from Mediterranean trade to an extent that made it the richest and one of the largest cities in Europe. In addition, amelioration on the mainland enhanced the yield, so that substantial profits flowed to Venice from here as well. With around 180,000 inhabitants, it almost reached its maximum population, with around two million people living in its colonial empire . The expansion of the city inwards, through land reclamation and drainage of swamps, through higher houses and denser development, accelerated. In addition, immigrants from the entire trading area increasingly shaped the city. Persians, Turks, Armenians, residents of the Holy Roman Empire, Jews and residents of numerous Italian cities found their own trading houses, quarters and streets. In addition to long-distance trade and the trade in salt and grain, the glass industry and shipbuilding grew to become the most important sources of income.

Wars for Northern Italy, loss of the colonial empire

Under the leadership of Pope Julius II , the League of Cambrai tried to reverse the Venetian expansion. Emperor Maximilian I reclaimed the Terra Ferma as an alienated imperial territory, Spain claimed the Apulian cities, the King of France Cremona , the King of Hungary Dalmatia. The Venetian army suffered a crushing defeat in the Battle of Agnadello on May 14, 1509. Despite this, the Serenissima managed to retake the lost Padua in the same year, and Brescia and Verona soon returned to Venice. Despite the reconquests, the Venetian expansion came to a standstill. Spain achieved extensive supremacy in Italy, the south fell entirely to him. In 1511, however, a new coalition was formed against the French expansion into Italy, from which Venice turned away again in 1513. From 1521 to 1522 and 1524 to 1525, Venice supported King Francis I of France against the Pope and the Habsburgs. From then on the republic pursued a policy of strict neutrality towards the Italian states , but allied itself again and again against the Habsburgs, for example in the League of Cognac (1526 to 1530).

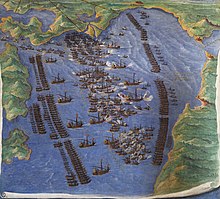

During the wars with the Ottomans from 1499 to 1503 and from 1537 to 1540 Venice was allied with Spain. In 1538 the admiral of the Federal Fleet , Andrea Doria , suffered a heavy defeat at Prevesa against the Ottoman fleet, which for the first time succeeded in asserting its superiority at sea. The Duchy of Naxos was taken over by the Ottomans. Due to its comparatively small resources, Venice was only able to play with great difficulty in the concert of the great powers of the time. From 1545 onwards, the city was forced, like other sea powers, to use galley prisoners who were chained to the rowing bench.

Venice played a political role for the last time in 1571 when it contributed 110 galleys to the Alliance fleet as part of the Holy League , which comprised a total of 211 ships. In the sea battle of Lepanto , not far from the Greek Patras , this fleet was able to defeat the Ottoman and conquer 117 of their 260 galleys . But Venice could not take advantage of it - the island of Cyprus had been lost before the sea battle (the loss of the island was contractually recognized in 1573) and the forces for a reconquest had long been lacking. In addition, the Ottoman fleet soon comprised 250 warships again.

From the perspective of the Venetians, the Turkish wars (five to date) continued to have top priority. In doing so, they tried not to get drawn into the disputes that the Uskoks repeatedly triggered through their piracy. The Uskoks were Christian refugees from the Turkish-occupied areas of Bosnia and Dalmatia. After Lepanto they were settled as subjects of the Habsburgs in the border areas for defense. When Venice took military action against them in 1613 and attacked Gradisca , it found itself in a multi-year conflict with the Habsburgs, which could not be resolved until 1617. In that year the Spanish viceroy of Naples tried to break the supremacy of Venice in the Adriatic - with little success. The Spanish ambassador involved in this was recalled and three of his men were hanged. The mistrust of Spain's intrigues went so far that in 1622 the innocent ambassador Antonio Foscarini - as it turned out later - was executed between the pillars of the piazzetta. The city was politically divided. On the one hand, the so-called giovani fought back . the boys. against the interference of the Pope in the politics of Venice and supported the Protestant rulers across confessional boundaries. They also mistrusted the Catholic Habsburgs, especially the Spanish. The leader of this anti-papal and anti-Jesuit group, which did not want to grant the Pope any privileges in worldly matters, was Paolo Sarpi . The opponents of the giovani were the vecchi , the ancients, also called papalisti , supporters of the pope. They supported Spain, which already ruled most of Italy.

In 1628 Venice was drawn into the struggle for the balance of power within Italy by the French Charles von Gonzaga-Nevers . Venice allied with France against the Habsburgs, who were in alliance with Savoy . The Venetians suffered a heavy defeat in trying to relieve Mantua from the German besiegers. This defeat, combined with the 16-month plague from 1630 to 1632, which cost Venice, a city of 140,000 people, around 50,000 lives, marked the beginning of its foreign policy decline. The church of Santa Maria della Salute was built in thanks for the end of the disaster.

In 1638 a Tunisian-Algerian corsair fleet invaded the Adriatic and withdrew to the Ottoman port of Valona. The Venetian fleet bombarded the city, hijacked the pirate fleet and freed 3,600 prisoners. The conquest of Crete was now being prepared at the Sublime Porte. The siege of the capital Candia (Iràklion) lasted 21 years. At the same time, Turkish naval units attacked Dalmatia, which, however, could be held. However, Candia capitulated on September 6, 1669. The last fortresses around Crete lasted until 1718.

Change in the ruling family associations

The rule of the nobility remained stable in spite of the external tremors, and the estate was sharply delineated from the outside. In 1594 Venice had 1,967 nobles at least 25 years old who gathered in the Grand Council and represented the nobility as a whole. During the battle for Crete , this nobility exceptionally allowed the admission of a hundred new families against payment of 100,000 ducats in order to be able to bear the burden of the war. Nevertheless, according to this aggregation , the 24 "old families" (case vecchie) still dominated politics, which could be traced back to the time before 800. In addition, there were about 40 other families who had access to the core area of exercise of power through numerous offices. Occasionally, new families pushed their way into the innermost, less clearly delimited core of power, and others had to leave it. Despite the aggregation, the number of nobles fell to only 1703 by 1719, which were divided into around 140 families with numerous branches. Their bond with one another was facilitated by the fact that the brothers represented a trading company within a family without a contract.

The distribution of wealth was raised within the taxable nobility - which was an exception in Europe - in 1581, 1661 and 1711. Of the 59 households that had an annual income from their houses and properties of more than 2,000 ducats per year, in 1581 only three were not noble. In 1711, of the 70 heads of households who received more than 6,000 ducats, only one was not a member of the nobility. With a few exceptions, wealth and nobility were practically identical.

This does not take into account the mobile assets that could be analyzed using the wills. Deposits with the Zecca , the state mint, played a major role in this, as in the 14th century with the wheat chamber, the camera del frumento . Alvise da Mosto, who died in 1701, had deposited 39,000 ducats there. In addition, there were deposits in family businesses, such as that of Antonio Grimani, who had invested 20,000 ducats in a soap factory by 1624. In addition, trading in the products of their own goods, such as grain and cattle, contributed significantly to wealth. The nobility acquired almost 40% of the communal land on the mainland, especially between around 1650 and 1720. Also important were dowries , which varied between 5,000 and 200,000 ducats, as well as income from state and church offices.

A total of about 7,000 people belonged to the nobility, who ruled the city with around 150,000 inhabitants and the colonial empire with 1.5 to 2.2 million inhabitants , politically and economically. The exercise of power continued to take place in a cycle of over 400 offices reserved for the nobility, which were mostly exercised annually, apart from the doge and the procurators and a few other offices that were awarded for life. A professionalization of politics in the sense of an apprenticeship or a degree has never caught on in Venice.

Last conquests in Greece

Only after the Second Turkish siege of Vienna by the Ottoman army had failed in 1683 , it was possible to forge a new alliance. In 1685 a Venetian army landed under Francesco Morosini and Otto Wilhelm von Königsmarck on Santa Maura (Lefkas), then on Morea (today's Peloponnese), conquered Patras , Lepanto and Corinth and advanced to Athens . In 1686 Argos and Nauplia were taken. The reconquest of Euboea failed in 1688. Although the Venetian fleet won sea victories at Mytilini , before Andros and even the Dardanelles (1695, 1697 and 1698), the actual victors, the Austrian Habsburgs and Russia , did not take Venice's demands seriously. After all, the Peace of Karlowitz in 1699 only marginally secured the conquests of Venice, after all the Morea peninsula remained Venetian for some time.

In December 1714, the Ottomans began the reconquest. Daniele Dolfin, admiral of the Venetian fleet, was not prepared to put it at risk for the Morea peninsula. In 1716 the commander in chief of the land troops, Field Marshal Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg , repulsed the Turkish siege of Corfu . Despite this victory and the defeats that the Ottomans suffered at the same time against the Habsburg armies under Prince Eugene of Savoy , Venice did not succeed in getting Morea back, whereas the Habsburgs made great territorial gains in the Peace of Passarowitz (1718). This war was the last between the Ottoman Empire and Venice. Venice's colonial empire , the Stato da Mar , consisted largely only of Dalmatia and the Ionian Islands . With a realistic assessment of the remaining forces, Schulenburg prepared these properties for their final defensive battle in the following decades.

Decline and end

Decisive for the gradual decline of Venice as a trading power, and thus as a European power factor, was the increasing loss of importance of trade in the Levant in the Age of Discovery and the accompanying rise of new powers. These powers also had forms of organization and credit that were not available in Venice. Due to its geographical location and the misjudgment of the importance of the discoveries of the newly developed resources of the New World and East India and thus cut off from the shifting trade flows ( Atlantic triangular trade and Indian trade ), Venice became economic and economic thanks to the emerging states of Portugal , Spain , the Netherlands and Great Britain gradually outstripped by power politics. In addition, due to its relatively small population and the lack of colonies rich in raw materials, it did not have the possibilities of a mercantile economic policy on a large scale. Only the producers of glass beads gained huge new markets through the trade of the new colonial powers in America, Asia and Africa. In Europe, Venice specialized in luxury goods, especially glass, and agriculture.

Venice and the Italian city-states as a whole sank from regional to local powers, and agriculture became the main field of activity of a growing section of the nobility.

Nevertheless, Venice succeeded in expanding its defenses that still exist today, a system that practically enclosed the entire lagoon and that was created between 1744 and 1782. In addition, Venice by no means stayed out of the conflicts, as in the Maghreb . In 1778 his fleet operated off Tripoli , from 1784–1787 a war ensued with Tunisia, led by Angelo Emo's fleet, in 1795 with Morocco and in October 1796 with Algiers .

On his Italian campaign , Napoleon offered Bonaparte an alliance, but the Senate refused. Instead, he supported the armed uprising on Terra ferma when Bonaparte pulled against the Austrians. From 1796 onwards, the whole of Northern Italy had become a battlefield for the French and Austrian troops. On April 15, 1797, the French general Andoche Junot gave the Doge an ultimatum accusing the republic of treason, which the republic did not accept. After the French fleet was repulsed by the cannons on the Lido on April 17th, Napoleon declared that he wanted to be the "Attila for Venice". On April 18, in a secret amendment to the Leoben Peace Treaty, it was agreed between France and Austria that Veneto , Istria and Dalmatia should fall to Austria. A week later, on April 25th, a French fleet lay in front of the Lido . Venice's cannons sank a ship and its captain, but the arrival of the French could not be stopped.

On May 12, the 120th and last doge, Ludovico Manin , resigned from office without any resistance in favor of a provisional administration, the municipalità provvisoria. Two days later he left the Doge's Palace forever. On May 16, foreign troops stood in St. Mark's Square for the first time in Venice's history . On the same day the surrender treaty was signed and Venice submitted to French rule. June 4th, the day a Provisional Government was established, was declared a national holiday as the Revolutionary Day of Freedom . There were only 962 patricians left from 192 families, almost all of whom lost their offices.

In the Treaty of Campoformio of October 17, 1797, Veneto , Dalmatia and Istria fell to Austria as the Duchy of Venice , and the Republic of the Ionian Islands to France. On January 18, 1798, the occupation of the city by the Habsburg Monarchy began with the entry of his troops .

From 1805 to 1814 Venice was again under French sovereignty after the Peace of Pressburg (as part of the Kingdom of Italy ). A significant part of his historical art treasures and archive materials were brought to Paris . After the final suppression of Napoleonic rule in Europe and the Congress of Vienna, which initiated the Restoration , it fell back to Austria in 1815 together with Lombardy (see Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia ), but only some of the works of art and archive items returned.

The city rose in the course of the revolutions of 1848 (for Italy see under Risorgimento ) against the Habsburgs and, under the leadership of the democratic-republican revolutionary Daniele Manin, proclaimed the Repubblica di San Marco on March 23, 1848 . This was put down by Austrian troops on August 23, 1849. After the defeat of the Habsburgs in the war against Prussia and Italy , Venice was annexed to the Kingdom of Italy , which was proclaimed in 1861 .

In 1997, on the 200th anniversary of the end of the Republic, eight men hijacked a ferry and brought sheet metal armor from the Lido to St. Mark's Square, where they hoisted the war flag of Venice on the bell tower of St. Mark, which shows St. Mark with a sword. The eight squatters, known as “lions” or “serenissimi”, were sentenced to prison terms of up to six years, but were released after one year.

Sources and Editions

The density of the medieval Venetian tradition can only be compared with that of the Vatican. Above all from around 1220, the protocols of the council bodies also come into play, and there are also countless sets of rules for corporations, major industries and financial administration.

The number of source editions is still small in relation to the holdings of the State Archives , the Biblioteca Marciana and the Museo Civico Correr . In historiography , this has to do with the fact that four authors have repeatedly copied: Andrea Dandolo , his successor Raffaino Caresini, Nicolo Trevisan and Giangiacopo Caroldo . Martino da Canale and the city praise of Marino Sanudo were also important authors . Since Venice strictly controlled the state historiography and appointed appropriate authors, non-Venetian writings are an important corrective.

Diplomatariums are available for the early Middle Ages , as are the editions of the Imperial Pacta and the numerous treaties with Italian cities. The editions by Tafel and Thomas on the earlier commercial and state history of the Republic of Venice are of particular importance for the transmission of documents.

The oldest surviving minutes were created in the Small Council and date from the years 1223 to 1229. For the period from 1232 to 1299, the minutes of the Great Council edited by Roberto Cessi are a main source.

The Council of Forty (the XL) is typical for the division of existing bodies in accordance with narrower competencies . It was created around 1220, rose to become an important body, but lost its political significance in the course of the 14th century and became the court of justice. The XL Nuova for civil law was created in the 14th century, leaving the old XL with criminal law. Around 1420 this was again divided according to new criteria for the allocation of competencies, so that now, in addition to the Quarantia Criminal , there was also talk of the Quarantia Civil Vecchia , or Nuova . The oldest surviving volume contains the resolutions of 1342/1347. The previous volumes have been lost, the surviving volumes are in poor condition. Antonino Lombardo prepared the three-volume edition, which covers the period from 1342 to 1368.

Particularly important for the 14th and 15th centuries are the Senate collections, especially Misti , Secreta and Sindicati . The Misti consist of 60 volumes for the years 1293 to 1440, but the first 14 have been lost. Volumes 1–14 contain (almost) only the headings of 4,267 resolutions, the unedited volumes 15 to 60 contain over 7,000 sheets. The Secreta started regularly from the year 1401 and comprises 135 volumes with 10 register volumes. Only four more of the original 19 volumes have survived from the 14th century ( Libri secretorum collegii rogatorum 1345–1350, 1376–1378, 1388–1397), so that a total of 139 volumes for the period from 1401 to 1630 are available. They represented the register in which magistrates and archivists could help themselves. The Sindicati are exclusively instructions to magistrates or envoys from the Senate (see Venetian Diplomacy ). In particular, the registers for the years 1329–1332 are of great importance, as only the Misti rubrics are available for this period .

The editions for the 14th century are the Notatorio del Collegio (1327–1383), the Secreta Collegii , the Liber secretorum Collegii Volume I (1363–1366) and (1408–1413), and finally the Regesta of the resolutions of the Collegio edited by Predelli , the Grand Council and the Senate (Regesti dei Commemoriali) .

The Council of Ten also left records, of which Ferruccio Zago has now published 5 volumes.

The most important fund for colonial history are the resolutions of the Duca di Candia , Lord of Crete. A collection of complaints on piracy in the Aegean has already been published by Tafel and Thomas. It illuminates the relationships between 1268 and 1278.

The numerous inscriptions of Venice were edited by Cicogna .

The tradition of diaries does not begin until the 15th century. Those of Girolamo Priuli and Marin Sanudos the Younger are particularly important .

The merchant's letters and books are of great importance for economic history, such as the letters of Pignol Zucchello or the (unedited) letters of Bembo for the late 15th century and the Pratiche della mercatura (merchant's handbooks ) by Giovanni da Uzzano, Benvenuto Stracca and many others Francesco Balducci Pegolotti. This also applies to the famous Zibaldone da Canal and the Tariffa de pesi e mesure by Bartholomeo di Pasi. The accounts books of Giacomo Badoer, which cover the years 1436–1439, have been edited, but have hardly been cataloged.

The numerous statutes (mariegole) are important for the history of the guilds and crafts . In the late Middle Ages, the records of the large, official and state bank-like institutions, such as the salt (Provveditori al Sal) and the grain chamber (Provveditori alle Biave), which are not edited.

Huge source editions, on the other hand, especially in the 19th century, were compiled under spatial aspects. These include the editions for Albania, the Belgrade Acta that concern Serbia, the counterpart from the Croatian Zagreb , then for Friuli, Istria, Ferrara, for the Levant and Romania or for Crete.

The Documenti finanziari were compiled less according to spatial than according to financial-historical criteria .

Maps and city plans became a precise source early on, as evidenced by the map by Iacopo de Barbari from 1500, whose printing blocks are in the Biblioteca Marciana .

literature

- Nicola Bergamo: Venezia bizantina , Helvetia editrice, Spinea 2018. ISBN 978-8895215686

- Andrea Castagnetti: La società veneziana nel Medioevo , Volume 1: Dai tribuni ai giudici , Volume 2: Le famiglie ducali dei Candiano, Orseolo e Menio e la famiglia comitale vicentino-padaovana di Vitale Ugo Candiano (secoli X – XI) , Verona 1992 / 1993.

- David Chambers (Ed.): Venice. A documentary history, 1450–1630 , Oxford 1992. ISBN 0-631-16383-2

- Helmut Dumler : Venice and the Doges , Düsseldorf 2001. ISBN 3-538-07116-0

- Ekkehard Eickhoff : Venice - late fireworks. Gloss and Downfall of the Republic 1700–1797 , Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2006. ISBN 3-608-94145-2

- Kurt Heller : Venice. Law, Culture and Life in the Republic 697–1797 , Böhlau, Vienna 1999. ISBN 3-205-99042-0

- Manfred Hellmann : Principles of the history of Venice , 2nd edition, Darmstadt 1989. ISBN 3-534-03909-2

- Achim Landwehr : The creation of Venice. Space, Population, Myth 1570–1750 , Schöningh, Paderborn 2007. ISBN 978-3-506-75657-2

- Reinhard Lebe : When Markus came to Venice - Venetian history under the sign of the St. Mark's Lion , Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-421-06344-3 .

- Ralph-Johannes Lilie : Trade and politics between the Byzantine Empire and the Italian municipalities Venice, Pisa and Genoa in the epoch of the Komnenen and Angeloi (1081–1204) , Amsterdam 1984. ISBN 90-256-0856-6

- Thomas F. Madden : Enrico Dandolo and the Rise of Venice , Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2003. ISBN 0-8018-7317-7

- John Julius Norwich : A History of Venice , Knopf / Random House, New York 1982 (2nd edition 2003), ISBN 0-14-101383-4

- Gerhard Rösch : Venice. History of a Maritime Republic , Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2000.

- Peter Schreiner (Ed.): Il mito di Venezia. Una città tra realtà e rappresentazione , Rome / Venice 2006.

- James E. Shaw: The Justice of Venice: Authorities and Liberties in the Urban Economy, 1550-1700 , Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006. ISBN 0-19-726377-1

- Alberto Tenenti , Ugo Tucci (eds.): Storia di Venezia , 8 volumes, plus 3 volumes (L 'Ottocento e il Novecento) and 3 themed volumes ( Il Mare , 2 volumes L'Arte ), Rome 1992–2002.

- Alvise Zorzi : Venice. A city, a republic, a world empire 697–1797 , Amber, Munich 1981. ISBN 3-922954-00-6

Web links

- State Archives website (ital.)

- Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia (Italian / English)

- Fondazione Giorgio Cini (Italian / English)

- more detailed version, further articles on Venetian history (private site)

- Detailed history (timetable) ( Memento from March 20, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (Italian, version from March 20, 2008 available)

- Giuseppe Tassini's “Curiosità Veneziane” with explanations of numerous names of Venetian streets, squares and other places

- Alphabetical list with illustrations of 138 palaces in Venice

- Campiello-Venise alphabetically arranged monuments of the city, with numerous photographs (French)

Remarks

- ↑ Gina Fasoli called her story of Venice (Florence 1937) simply La Serenissima .

- ↑ In German-language literature, the term nobility has largely established itself for the families active in long-distance trade and politically leading families ( Dieter Girgensohn : Church, Politics and Noble Government in the Republic of Venice at the beginning of the 15th century. (= Publications by Max Planck) Institute for History. Volume 118). 2 volumes. Göttingen 1996; Gerhard Rösch : The Venetian nobility up to the closure of the Grand Council: on the genesis of a leadership class. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1989 et al.). By contrast, Alexander Francis Cowan: The Urban Patriciate: Lübeck and Venice 1500–1700. Cologne / Vienna 1986.

- ↑ Still a good access to the sources: Andrea da Mosto: L'Archivio di Stato di Venezia. Indice generale, storico, descrittivo ed analitico. 2 volumes. Rome 1937 and 1940.

- ↑ On the early history of the lagoon cf. Vladimiro Dorigo: Storia delle dinamiche ambientali ed insediative nel territorio lagunare veneziano , Venice 1994.

- ^ Graziano Tavan: Archeologia della Laguna di Venezia. In: Veneto Archeologico January / February 1999 .

- ↑ This is what the Chronicon Altinate claims .

- ↑ Fundamental to the history of events and of great knowledge of the sources is still: Heinrich Kretschmayr : History of Venice , 3 volumes, Gotha 1905 and 1920, Stuttgart 1934 (reprint: Aalen 1964 and 1986, ISBN 3-511-01240-6 ).

- ↑ Luprio roughly corresponded to today's sixths of the city Santa Croce and San Polo . A luprio was a drained swampy area. There were numerous salt pans there .

- ↑ This formed the core of what is now the Cannaregio district .

- ↑ The district joined Rivoalto to the east.

- ↑ This was one of the seven islands that later formed the sixth of the city, Dorsoduro .

- ↑ The Church of San Zaccaria is located there today .

- ↑ Spinalunga today forms part of the Giudecca .

- ↑ This and the following, essentially based on Donald M. Nicol: Byzantium and Venice. A study in diplomatic and cultural relations. Cambridge University Press 1988.

- ^ Cassiodorus , Variae, X, 27 and XII, 24.

- ↑ Constantin Zuckerman: Learning from the Enemy and More: Studies in “Dark Centuries” Byzantium , in: Millennium 2 (2005) 79–135, especially pp. 85–94.

- ↑ The Longobard Empire had a similar tradition-building effect on Venice, because from there the commune took over the office of Gastalden .

- ↑ In addition: Johannes Hoffmann: Venice and the Narentaner , in: Studi Veneziani 11 (1969) 3-41.

- ^ Theodor Schieder : Handbook of European History , Volume 1: Europe in Change from Antiquity to the Middle Ages , Stuttgart: Cotta 1976, 4th edition. 1996, p. 394.

- ↑ On the expansion of rule over the upper Adriatic Sea, the Gulf of Venice : Antonio Battistella: Il dominio del Golfo , in: Nuovo Archivio Veneto, nuova series 35 (1918), pp. 5–102. Walter Lenel : The emergence of the supremacy of Venice on the Adriatic , Strasbourg 1897.

- ↑ See Johannes Hoffmann: Venice and the Narentaner , in: Studi Veneziani 11 (1969) 3-41.

- ↑ Hubertus Seibert : A great father's hapless son? The new politics of Otto II. , In: Bernd Schneidmüller , Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): Ottonische Neuanfänge. Symposium on the exhibition "Otto the Great, Magdeburg and Europe" , Mainz 2001, pp. 293-320.

- ↑ A great father's hapless son? The new politics of Otto II. , In: Ottonische Neuanfänge , edited by Bernd Schneidmüller and Stefan Weinfurter , Mainz 2001, pp. 293-320, here: p. 309.

- ↑ General on Venice's commercial privileges in Byzantium: Julian Chrysostomides: Venetian commercial privileges under the Palaeologi , in: Studi Veneziani 12 (1970) 267–356.

- ↑ Particularly noteworthy is the so-called Liber plegiorum, a paper codex that was created from 1223 (Roberto Cessi (ed.): Liber Plegiorum & Acta Consilii Sapientum (= Deliberazioni del Maggior Consiglio di Venezia, 1), Bologna 1950.

- ↑ On the relativization of the term foreign policy last: Hanna Vollrath (Ed.): The way in a wider world. Communication and “Foreign Policy” in the 12th Century , LIT Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-8258-6856-7 .

- ^ Giorgio Cracco : Societé e stato nel medioevo veneziano , Florence 1967, p. 110. The oldest surviving lists of members of the Grand Council are from the years 1261 (27 families with 242 members) and 1282. In 1284 the Great Council had 370 members; 1286 144, 1296 366. In 1297 it was expanded from 588 to approx. 1,100. Councilors 1310: 900; 1311: 1017, 1340: 1,212, around 1460: approx. 2,000, 1493: 2,420; 1510: 1,671, 1513: 2,570-2,622, 1527: 2,746, 1550: 2,615, 1563: 2,435, 1575: 2,500-3,000, 1594: 1,970, 1620: approx. 2,000, 1631: 1,160; 1714: 2,851; 1718: ca.1,700, 1797: 1,196.

- ↑ Cf. Gerhard Rösch : The Venetian nobility up to the closure of the Grand Council: on the genesis of a leadership class , Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1989, especially pp. 168–184.

- ^ Frederic C. Lane: Maritime Republic of Venice , Munich 1980, p. 182.

- ^ Dennis Romano: Patricians and Popolani: The Social Foundations of the Venetian Renaissance State. Baltimore 1987, pp. 141-158.

- ↑ Monumenta Germaniae Historica , Const. 72, p. 121.

- ↑ Franz Dölger (Ed.): Regest of the imperial documents of the Eastern Roman Empire from 565-1453 , 2nd part: from 1025-1204, Munich 1925, n. 1081, May 1082. On this Chrysobullon cf. Ralph-Johannes Lilie: Trade and politics between the Byzantine Empire and the Italian communes Venice, Pisa and Genoa in the epoch of the Komnenen and Angeloi (1081–1204), Amsterdam 1984. The Doge was given the title of Protosebastus , one of the highest awarding title of the Eastern Empire ( Famigliazuto (1083–1199), ed. Luigi Lanfranchi , Venice 1955, n. 1, 1085).

- ^ John Danstrup: Manuel I's coup against Genoa and Venice in the light of Byzantine commercial policy , in: Classica et Mediaevalia 10 (1948) 195-219; on the trading quarters of the Venetians in Constantinople: Eric R. Dursteler: Venetians in Constantinople. Nation, identity, and coexistence in the early modern Mediterranean , The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore / London 2006, ISBN 0-8018-8324-5 .

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Hübner: Quia bonum sit anticipare tempus. The municipal supply of Venice with bread and grain from the late 12th to the 15th century , Peter Lang, 1998, pp. 111–198.

- ↑ On Enrico Dandolo: Thomas F. Madden : Enrico Dandolo & the rise of Venice , Baltimore 2003, ISBN 0-8018-7317-7 .

- ↑ Still fundamental: Freddy Thiriet: La Romanie vénitienne au Moyen Age. Le développement et l'exploitation du domaine colonial vénitien (XII – XV siècles) , Paris 1959, 2nd edition, Paris 1975.

- ↑ Still the best presentation: Vittorio Lazzarini: La presa di Chioggia , in: Archivio Veneto 81 (1952) 53–64.

- ↑ On his relations with Venice, cf. Francesco Carabellese: Carlo d'Angiò nei rapporti politici e commerciali con Venezia e l'Oriente. Bari 1911.

- ↑ On the policy of Emperor Andronikos II. Cf. Angelik Laiou: Constantinople and the Latins: The Foreign Policy of Andronicos II., 1282-1328 , Cambridge / Massachusetts 1972.

- ^ Antonio Battistella: Contributo alla storia delle relazioni tra Venezia e Bologna, Atti dell'Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, Volume 35, Venice 1915f. and Alfred Hessel: History of the City of Bologna 1116 to 1280. Berlin 1910.

- ↑ Mario Brunetti: Venezia durante la peste del 1348 , in: Ateneo Veneto 32 (1909) 289-311.

- ^ On the politics and economy of Venice in the 14th century: Roberto Cessi : Politica ed economia di Venezia nel trecento , Rome 1952.

- ↑ On this imperial age : David S. Chamber: The Imperial Age of Venice , New York / London 1970.

- ↑ On this Europe-wide war: Wolfgang v. Stromer : land power versus sea power. Emperor Sigismund's continental barrier against Venice 1412–1433 , in: Journal for historical research 22 (1995) 145–189.

- ^ Dennis Romano: The Likeness of Venice. A Life of Doge Francesco Foscari 1373-1457 , Yale University Press, New Haven 2007.

- ↑ The island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni was not inhabited by Armenians until 1717.

- ↑ On population development cf. Karl Julius Beloch : Population history of Italy , Volume 3: The population of the Republic of Venice, the Duchy of Milan, Piedmont, Genoas, Corsica and Sardinia. The total population of Italy , Berlin 1961, Section VII The Republic of Venice .

- ↑ Basically : Elisabeth Crouzet-Pavan : “Sopra le acque salse”. Escpaces, pouvoir et société à Venise à la fin du Moyen Age , 2 volumes, Rome 1992.

- ↑ There are numerous works on this, Robert C. Davies stands out in terms of social history: Shipbuilders of the Venetian Arsenal. Workers and workplace in the preindustrial city. Baltimore / London 1991, out.

- ^ Angus Konstam: Lepanto 1571. The greatest naval battle of the Renaissance , Oxford 2003.

- ↑ See Murray Brown: The Myth of Antonio Foscarini's Exoneration. In: Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Reforme , Société Canadienne d'Études de la Renaissance 25 (2001) 25–42.

- ^ Venezia e la Peste. 1348–1797 , exhibition catalog, Venice 1980.

- ↑ This and the following according to: Peter Burke : Venice and Amsterdam in the 17th century , London 1974, German Göttingen 1993; Oliver Thomas Domzalski: Political Careers and Distribution of Power in the Venetian Nobility (1646–1797) , Sigmaringen 1996.

- ↑ Susanna Grillo: Venezia. Le difese a mare. Venice 1989.

- ↑ On Napoleon's relationship to Venice: Amable de Fournoux: Napoléon et Venise 1796–1814. Editions de Fallois 2002, ISBN 2-87706-432-8 .

- ↑ On these losses cf. Maria Luxoro: La Biblioteca di San Marco nella sua storia , Florence 1954.

- ↑ Thomas Götz: Venice's tower squatters at large. Mayor campaigns for separatists. In: Berliner Zeitung . April 29, 1998, accessed June 16, 2015 .

- ^ Giovanni Monticolo , Ernesto Besta (ed.): I capitolari delle arti Veneziane , Rome 1905–1914.