Wealth distribution

In economics, wealth distribution describes the distribution of wealth in regional , national or global terms. In addition, a distinction is made between the sectoral distribution of wealth (which examines the economic sectors of an economy ) and the personal distribution of wealth.

The distribution of wealth is nationally and globally more unequal than the distribution of income . In recent years, wealth inequality has increased worldwide, in Germany and in Austria . It should be noted, however, that when calculating the distribution of assets, only property, monetary and investment assets are taken into account and that state and private pension commitments, which are of major importance in the individual asset assessment, are not taken into account in the calculation. Since a large part of the wealth, especially of the super-rich, is barely recorded, wealth inequality, both nationally and internationally, is probably higher than official figures suggest.

The financial assets of companies around the world are also highly concentrated. The aim of wealth policy is to influence the personal distribution of wealth.

Basic distinctions

Sectoral wealth distribution

The sectoral distribution of wealth is a result of the wealth calculation according to economic sectors , a subsidiary calculation of the national accounts . It determines the distribution of the total wealth of an economy among individual economic subjects ( private households , companies and the state ), residents and foreigners, and down to economic sectors .

Personal wealth distribution

The personal distribution of assets deals with the distribution of assets among individuals or groups of people, broken down into different categories. An illustration of wealth or income inequality that is well-known beyond the medical community is Pen's Parade . The further article deals exclusively with personal wealth distribution according to the following aspects:

- The breakdown into asset size classes (asset stratification) is usually carried out in such a way that the individual persons or households are divided into asset size classes depending on the amount of assets. Often four, five or ten classes or quantiles (quartiles, quintiles, deciles) are formed. The 10% of households with the lowest individual income are in the bottom decile, and the richest 10% in the top. A common graphic representation is the Lorenz curve .

- The breakdown according to asset size classes shows that in practice assets are not evenly distributed, but that there is a concentration of assets in the upper quantiles. This structure is the most widely discussed form in science and politics. The causes of this unequal distribution, the fairness of distribution and the possibilities of influencing this (in the sense of a more even distribution) are discussed.

- A breakdown by age, generations, (professional) qualifications and gender serves to explain the causes of the asset stratification.

- A breakdown according to states and regions serves to compare different states, regions, cultures or economic systems with regard to capital formation , capital flight and distributive justice. In the regional planning and regional policy the distribution of wealth is an essential parameter. See also the list of countries by wealth distribution .

- A breakdown according to asset types (e.g. financial assets , real estate assets ) is used to analyze what effects phenomena such as inflation , economic growth or the like have on the distribution of assets.

- A breakdown according to socio-economic groups (e.g. self-employed, employees, etc.) is used to analyze sociological and economic issues such as economic power .

Definitions

The assets of a natural person is made up of goods with economic value along who is a person; their distribution is the distribution of wealth. In contrast, income denotes the influx of goods with economic value in a certain period of time; their distribution is the distribution of income .

Distribution measures

The inequality of a distribution is indicated by inequality measures. The Gini coefficient is most commonly used for this . It is specified as a number between 0 and 1. A Gini coefficient of 1 represents absolute unequal distribution (1 person owns everything, all others nothing), 0 means absolute equal distribution (all people have the same wealth).

Another, simple measure is the Hoover unequal distribution , which describes the deviation from the mean of all wealth. Other common measures are the Theil index and the Atkinson measure .

Problems of recording wealth

Various methodological and statistical problems arise in the study of wealth distribution. Certain components of wealth are difficult to capture. It is difficult to obtain an exact listing of the material assets . Another problem is that surveys and surveys make it difficult to record high wealth in a society. A significant proportion of very high assets are hidden in tax havens . Institutions such as the Tax Justice Network assume that wealth inequality in all societies is more unequal than previous studies, because all studies on economic inequality systematically underestimate the wealth and incomes of the world's richest people. (...) If assets are hidden in a bank account, trust or company offshore and the ultimate owners or beneficiaries of the income or capital cannot be identified, these assets and their income will not be counted in the inequality statistics . Almost all of these hidden assets belong to the world's wealthiest individuals. It follows that inequality statistics, especially at the higher end of the scale, underestimate the problem.

A crucial problem is the unwillingness to participate in certain population groups in a survey . Another problem is capturing the market value of most assets, especially assets inherited or purchased long ago, and also business assets .

Natural resources, land, works of art, household assets, intangible assets such as patents and licenses, labor assets and pension assets (pension entitlements) are named as asset components that are difficult to estimate and therefore often neglected. This makes international comparison difficult. For example, while old-age provision in the USA is based on the principle of individual funding and is counted as assets there, in Germany it is organized according to the pay-as-you-go system and statutory pension entitlements are not included in the distribution of assets.

Distribution of wealth by region

Worldwide wealth distribution

→ see also list of countries according to wealth distribution

Wealth is much more unevenly distributed than income. Inequality has increased over the past 20 to 30 years.

Inequality of the recorded wealth

Distribution of global private wealth in 2000 (as a percentage per tenth of the adult population)

According to a study, the Gini coefficient worldwide was 0.892 in 2000 . According to this, the richest percent of the world's population owns 40% of the world's wealth. The richest 10% together owned 85% of the world's wealth, the poorer 50% combined only 1%. The inequality value of 0.892 roughly corresponds to a situation in which out of 100 people one person owns 90%, while the other 99 people share the remaining 10 percent.

According to calculations by Oxfam , the asset concentration is even greater. According to Oxfam's 2014 calculations, the richest 85 people have the same wealth as the poorer half of the world's population combined. These 85 richest people, according to the report, are worth £ 1 trillion, the equivalent of the 3.5 billion poorest people. The wealth of the richest percent of the world's population continues to total £ 60.88 trillion. This concentration increased between 2014 and 2016. In 2016, the 62 richest people combined had as much wealth as the poorer half of the world's population. Oxfam cites tax havens as an important reason for the increase in concentration.

Financial wealth inequality, including hidden wealth

In the opinion of many economists, the inequality of wealth at the national and global level is significantly higher than most studies indicate because a large proportion of wealth is not taken into account.

The Tax Justice Network refers to using data from the UN, the World Bank and Capgemini in an investigation into the offshore financial centers hidden fortune with one. The result: the unequal distribution of wealth, even according to official figures, is significantly more unequal.

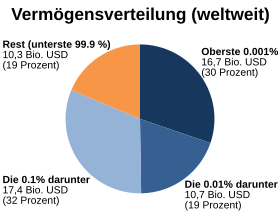

"Less than 100,000 people, that is 0.001% of the world's population, [control] more than 30% of the world's financial wealth."

The pie chart on the right shows the strong concentration of financial wealth alone for 2007. The richest 0.001%, around 90,000 people, own around 30% of financial wealth. The second 0.01%, around 800,000 people, own another 19%. The third 0.1%, 8 million people own another 32%. 99.9% of the people, over 6 billion people, share the remaining 19%. According to this, fewer than 9 million people, around 0.1% of the world's population, own over 80% of the world's financial assets.

Number and distribution of dollar millionaires

| 2007 | worldwide | Africa | middle East | Latin America | Asia | Europe | North America |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of wealthy millionaires (in millions) | 10.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.3 |

| Total assets (in $ trillion) | 40.7 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 6.2 | 9.5 | 10.6 | 11, 7 |

| Number of super-rich (in thousands) (wealth over $ 30 million) |

103.3 | 2.1 | 4.4 | 10.2 | 20.4 | 25.0 | 41.2 |

The number of dollar millionaires worldwide - measured by net worth in US $ - is regularly documented in the World Wealth Report . The results for 2007:

Shares of different areas in world population and global private wealth in 2000 (in percent)

(*) LA. = Latin America (South America and Central America) (**) Rich Asia = here mainly Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Australia, New Zealand

Distribution of wealth in Europe

The following table shows the distribution of wealth in the euro area for 2012 according to a survey by Credit Suisse . A high Gini coefficient and a low average wealth compared to average wealth indicate a potentially high inequality of wealth in the respective country.

| country | Average wealth in € | Average assets in € | Gini coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luxembourg | 119000 | 215000 | 0.62 |

| France | 63000 | 206000 | 0.76 |

| Belgium | 93000 | 181000 | 0.66 |

| Italy | 96000 | 165000 | 0.65 |

| Austria | 63000 | 139000 | 0.69 |

| Germany | 33000 | 135000 | 0.78 |

| Netherlands | 48000 | 135000 | 0.81 |

| Ireland | 47000 | 118000 | 0.73 |

| Finland | 57000 | 113000 | 0.66 |

| Cyprus | 31000 | 87000 | 0.75 |

| Spain | 41000 | 81000 | 0.66 |

| Greece | 28000 | 70000 | 0.71 |

| Portugal | 22000 | 60000 | 0.73 |

| Malta | 25,000 | 48000 | 0.66 |

| Slovenia | 24000 | 45000 | 0.64 |

| Estonia | 11000 | 21000 | 0.66 |

| Slovakia | 11000 | 19000 | 0.62 |

Distribution of wealth in Germany

In an international comparison, Germany occupies a middle position, but within the euro area, the second highest position in terms of wealth inequality (2012). After the turn of the millennium or since the mid-1990s, inequality increased.

In 2007 the richest 10% of the population aged 17 and over owned 66.6% of total assets (according to in-depth calculations from 2011 by the DIW , taking into account the top assets), the richest 0.1% (around 70,000 people) with 1,627 billion euros 22.5% of total assets. The poorer half of the population (around 35 million people), on the other hand, owned 103 billion euros, only 1.4% of the total wealth and thus less than the ten richest Germans in the same year (113.7 billion). The Gini index of wealth distribution rose in 2007 compared to the previous study from 2002. According to the DIW study based on SOEP data published in 2014, the poorer 27.6% of the population in Germany had nothing or had more debts than assets in 2012. The Gini coefficient for wealth inequality was 0.78 in 2012 - but this does not include top wealth. Due to the limited amount of data available on particularly high wealth, the DIW assumes that the real wealth inequality is very likely to be significantly greater than was recorded in the study.

Distribution of wealth in Austria

The Austrian National Bank found a pronounced inequality in the distribution of net wealth in Austria for 2010. The richest 5 percent owned about 45% of the property, the poorer 50% about 4 percent. Pensions are not taken into account.

Distribution of wealth in the USA

The top 1% of American households controlled more than half of the equity of U.S. companies in 2019, according to the Federal Reserve . Those richest had fortunes of about $ 35.4 trillion in the second quarter, just under the $ 36.9 trillion owned by the 50th to 90th percentile of Americans. The bottom 50% of the population owned $ 7.5 trillion.

Comparison of wealth distribution across countries worldwide

Worldwide, the Gini coefficient for the year 2000 varies in the individual countries between 0.54 and 0.85, mostly between 0.65 and 0.75%. Compare the list of countries by wealth distribution and the more complete English version.

Concentration of the financial assets of companies

In 2007, 147 corporations controlled about 40% of the global financial assets of all international companies.

Causes of the unequal distribution and concentration of wealth

General basics for wealth accumulation

Inherited wealth, life cycle and personal abilities play the essential role for the inequality of wealth distribution.

Life cycle means that wealth creation is a process that usually takes place in phases. In many cases, there is little or no wealth during the training phase, wealth can increase during working life, and wealth often declines at retirement age due to asset transfers to the next generation. The prerequisite for this is to build up and save assets at all, naturally linked directly to the income situation.

The level of (formal) qualifications, professional position and income are further important determinants for asset accumulation.

Asset accumulation especially in high income areas

The last three factors mentioned, however, play only a subordinate, if not negligible role, especially in the very high income ranges. Another important factor are inheritances and gifts . After Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century , this was usually the most important reason in history for a concentration of wealth in capitalism, since the interest income from wealth has been many times more profitable than the income from gainful employment since 1800.

Particularly in the area of very high asset concentration, the low taxation of interest income and inheritances, or non-taxation of assets by far, plays the main role:

“Capital, which is taxed less than labor, uses part of the money it owes its political decisions to consolidate its political pillars: the fair taxation; the rescue of the big banks after the small savers were taken hostage; the pressure on the masses of the population to compensate the creditors; the national debt, which means additional investment opportunities (and additional leverage) for the rich. "

Monotonous increase in the dispersion of distribution excluding property and inheritance taxes

Joseph Fargione et al. Showed in 2011, based on the work of Mandelbrot , Stiglitz and Champernowne as well as theories on the random development of ecosystems, that the accumulation of wealth can be modeled mathematically as a very simple process in which random, normally distributed returns are distributed on the already existing wealth ( Interest on investments) (In reality the distribution is slightly different, but does not play a major role in the practical effects on asset concentration). He showed that the compound interest effect triggers a concentration process that leads to a logarithmic normal distribution of wealth. This enabled him to explain the origin of the distribution of wealth and to characterize existing distributions of wealth better with this model than with the Pareto distribution, which is often used for these purposes . His model shows in a simple way that without external intervention such as the application of property and inheritance taxes, over time all available wealth is concentrated in fewer and fewer people. The reason for this is the monotonous increase in the spread of the distribution, since the probability of achieving an increase in wealth is higher than that of a loss of wealth (positive average return), which means that there are practically no limits to the concentration of wealth.

However, if you introduce an annually recurring wealth tax in this process, the spread can no longer increase monotonously. As wealth increases, it becomes increasingly unlikely that the normally distributed return will enable higher wealth growth than would have to be paid through a fixed wealth tax. In Piketty's words, it does . As a result, the spread of the assets converges towards a limit value . Another consequence of a wealth tax is a constant distribution of wealth over time. The statistically observable distribution of wealth is in principle a variable that can be influenced . The amount and breadth of the application of a wealth tax therefore directly determines the degree of unequal distribution of wealth and the relationship between the accumulated wealth of the individual social groups.

A simulation of the distribution of wealth over the distribution of wealth in the Federal Republic of Germany shows a very good agreement with the observed wealth distributions.

Against the background of Fargione's findings, all of the aforementioned causes are therefore plausible. Within society, personal characteristics and skills determine the individual achievable share of total assets. However, social parameters, in particular the amount and assessment basis of wealth tax, inheritance tax and taxes on interest income, determine the achievable share of assets of the individual social groups .

Wealth mobility

In connection with the distribution of wealth, wealth mobility means that the wealth position of the individual changes significantly in the course of life compared to the total number of people considered. The most important reason for this is the life cycle. Of the people who were in the poorest tenth in 2002, only 33% were in the poorest tenth five years later, and two thirds had improved their wealth position. 77% rose from the fifth tenth. The downward mobility of wealth is only low in the richest tenth. 62% of those who were classified there in 2002 stayed there in 2007 as well.

Justice discussion

In addition to the question of how wealth is distributed , the discussion of wealth distribution often touches on the question of how wealth should be distributed . This deals with the discussion of distributive justice, in which the distribution of wealth is also an issue in addition to income distribution. The assessment of a specific distribution as just or unjust is always a political judgment. For such a judgment to be possible in the first place, all other conditions apart from the assets must first be comparable. For example, if a 17-year-old student has no assets and a 50-year-old employee has assets of 100,000 euros, there is wealth inequality. However, this inequality does not necessarily result in an injustice. In order to obtain a meaningful measure of injustice, the (statistical) disparity must therefore be broken down into two components:

- On the one hand there is objectively justified inequality (different age, income, propensity to save, etc.), which does not represent an injustice

- On the other hand, the remaining inequality (which is then relevant for an asset policy)

What is factually justified can also be disputed here. In addition, it can be difficult to obtain statistical data in the degree of detail that is desirable.

The American economist Morton Paglin therefore suggested focusing on age (which is easy to raise and undisputedly an aspect that is not relevant to justice). While the inequality can be represented graphically as the area between the degree of equality (G) and the Lorenz curve (L), Paglin introduces an age-Lorenz curve (A), which shows the wealth distribution corrected for the life cycle effect. This is much closer to the equality line. The much smaller area between G and A instead of G and L describes the part of the uneven distribution that cannot be "explained" by the life cycle alone.

The justice discussion also has a welfare-theoretical aspect : the macroeconomic benefit (the social welfare function) is the sum of the benefits of the individual economic participants. With the same utility function of all economic participants and given total income, social welfare is at its maximum with an exact equal distribution. The reason is that the marginal utility is falling. A dispossessed increases his benefit by a transfer of ownership more than the benefit of the giver decreases. It follows from this idea that an even distribution of wealth would also be economically advantageous. This idea is largely not shared in economics. The prerequisites are not met: the utility function of all economic participants is neither the same nor is the total income given.

Historical development

In pre-industrial times, land was the main asset. Its unequal distribution led to attempts at land reforms even in antiquity (e.g. the Gracchian reform ) . The degree of unequal distribution of wealth varied greatly from region to region. While large landowners predominated in settlement colonies or in Germany east of the Elbe and the land distribution was extremely uneven, the land distribution in the Rhineland was much more even.

In 1882 the following distribution of the size of the property of agricultural holdings was recorded in the German Reich.

| area | surface | <1 ha | 1 - 10 ha | 10 - 100 ha | > 100 ha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| German Empire | 5276344 ha | 2.4% | 25.6% | 47.6% | 24.4% |

| Alsace-Lorraine | 233866 ha | 5.0% | 51.8% | 35.9% | 7.3% |

| Bavaria | 681521 ha | 1.6% | 35.6% | 60.5% | 2.3% |

| East Prussia | 188,179 ha | 1.0% | 9.3% | 51.1% | 38.6% |

| West Prussia | 134026 ha | 1.3% | 9.1% | 42.5% | 47.1% |

| Pomerania | 169,275 ha | 1.3% | 10.1% | 31.2% | 57.4% |

With the onset of industrialization , the importance of non-real estate assets slowly increased and there was a division between town and country. While the poor residents in the country often had small areas of land, a garden or a house, a proletariat of poor workers emerged in the cities . In the middle of the 19th century, there was an upper class in Germany consisting of the upper class in the city and the aristocracy in the country, who made up 5% of the population and owned the vast majority of the wealth. Around 40% belonged to the middle class as small farmers or self-employed and had small assets. 55% of the population had little or no wealth.

Meaningful statistical figures are available from around 1890. The wealth tax statistics of the German Empire show that 7.5% of the population had wealth greater than 20,000 marks (and 90% paid the wealth tax), another 7.5% of the population owned between 6,000 and 20,000 marks (and paid 10% ). 85% had little or no wealth.

literature

- Dieter Brümmerhoff , Heinrich Lützel: Lexicon of national accounts. 1994, ISBN 3-486-22028-4 , pp. 404-407.

- Dieter Brümmerhoff: Finance. 10th edition. 2011, ISBN 978-3-486-70261-3 , pp. 257-260.

- James B. Davies, Susanna Sandström, Anthony Shorrocks, and Edward N. Wolff: The World Distribution of Household Wealth. Helsinki 2008, ISBN 978-92-9230-064-7 . (PDF)

Web links

- Stefan Bach Distribution of Income and Wealth in Germany . Federal Agency for Civic Education , February 27, 2013

- International Association for Research on Income and Wealth

- Merrill Lynch : World Wealth Report. June 2008. (Statistics on the people with the highest net worth in the world.) Retrieved July 17, 2008. (PDF)

- UN statistics - Distribution of Income and Consumption; wealth and poverty

- Research on the World Distribution of Household Wealth (UNU-WIDER)

supporting documents

- ↑ Redistribution dispute in Austria: A class struggle with bad cards. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . March 6, 2015, accessed Nov. 21, 2015.

- ↑ a b Dieter Brümmerhoff , Heinrich Lützel: Lexicon of national accounts. 1994, ISBN 3-486-22028-4 , pp. 404-407.

- ↑ Sometimes numbers between 0 and 100 are also used.

- ↑ a b Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka: Increased wealth inequality in Germany. (PDF; 276 kB). In: DIW Berlin weekly report. No. 4/2009, p. 58.

- ↑ Nicholas Shaxson , John Christensen, Nick Mathiason: Inequality: More Than Half Stay Hidden (Or why inequality is greater than we thought). on: taxjustice.net (PDF; 658 kB), 2012, p. 1.

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka, Richard Hauser: The distribution of wealth in Germany - empirical analyzes for people and households. Berlin 2010, p. 14.

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka: Increased wealth inequality in Germany. (PDF; 276 kB). In: DIW Berlin weekly report. No. 4/2009, p. 59.

- ^ Dieter Brümmerhoff, Heinrich Lützel: Lexicon of the national accounts. 1994, ISBN 3-486-22028-4 , p. 405.

- ↑ James B. Davies, Susanna Sandström, Anthony F. Shorrocks, Edward N. Wolff: Estimating the World Distribution of Household Wealth. Study by the International Association for Research in Income and Wealth (PDF; 16 kB)

- ↑ a b c World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNI-WIDER): Pioneering Study Shows Richest Two Percent Own Half World Wealth , December 2006.

- ↑ James B. Davies, Susanna Sandström, Anthony Shorrocks, Edward N. Wolff: The World Distribution of Household Wealth . Discussion Paper No. 2008/03, February 2008, p. 7.

- ^ Oxfam: 85 richest people as wealthy as poorest half of the world. In: The Guardian. 20th January 2014.

- ↑ World's 85 richest people have as much as poorest 3.5 billion: Oxfam warns Davos of 'pernicious impact' of the widening wealth gap. In: The Independent. 20th January 2014.

- ↑ 62 The super-rich own as much as half the world's population . News dated January 18, 2016.

- ↑ Revealed: global super rich has at least $ 21 trillion hidden in secret tax have. on: taxjustice.net

- ^ For example, Thomas Piketty , Sam Pizzigati , Milorad Kovacevic , Branko Milanovic , Martin Ravallion , Stewart Lansley , Kevin Watkins . Cf. Nicholas Shaxson , John Christensen, Nick Mathiason: Inequality: More than half remain hidden (or why the inequality is greater than we thought). on: taxjustice.net (PDF; 658 kB), 2012, p. 2.

- ↑ New insights into the price of offshore banking: key points. on: taxjustice.net p. 2.

- ↑ Revealed: global super rich has at least $ 21 trillion hidden in secret tax have. on: taxjustice.net

- ↑ World Wealth Report 2008 ( Memento of the original from January 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. or as download [World Wealth Report 2008 World Wealth Report 2008] (pdf, noscript required), accessed on January 24, 2013.

- ↑ FAZ-Online , accessed on March 11, 2013. Gini coefficient and the deviation of average wealth from mean wealth are econometric measures for the unequal distribution of wealth in an economy.

- ↑ Central bank report: Data on wealth only after Cyprus was bailed out. on: faz.net

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka: Increased wealth inequality in Germany. (PDF; 276 kB). In: DIW Berlin weekly report. No. 4/2009, p. 59, footnote 10.

- ↑ See E. Sierminska, A. Brandolini, T. Smeeding: Comparing Wealth Distribution across Rich Countries: First Results from the Luxembourg Wealth Study. Luxembourg Wealth Study Working Paper Series, Working Paper No. 1, 2006.

- ^ Distribution of income and wealth in Germany. on the website of the Federal Agency for Civic Education

- ↑ Stefan Bach, Martin Beznoska, Viktor Steiner: A Wealth Tax on the rich to bring down public debt? (PDF; 246 kB), DIW 2011, p. 11.

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka: Increased wealth inequality in Germany . (PDF; 276 kB). In: DIW Berlin weekly report , No. 4/2009, p. 57.

- ↑ Persistently high wealth inequality in Germany (PDF) Markus M. Grabka, Christian Westermeier, in DIW weekly report No. 9.2014, pp. 151–164.

- ↑ The wealth gap in Germany: the poor stay poor, the rich get richer. sueddeutsche.de, February 26, 2014, accessed on February 28, 2014 .

- ↑ Great statistical uncertainty regarding the share of the top wealthy in Germany (PDF) DIW weekly report No. 7.2015, p. 132

- ^ Richest 1% of Americans Close to Surpassing Wealth of Middle Class. In: Bloomberg. Retrieved August 2, 2020 .

- ↑ List of countries by distribution of wealth (WP)

- ↑ Financial world dominated by a few deep pockets . September 2011; Vol.180 # 7, p. 13. Science News . The network of global corporate control (PDF; 2.0 MB).

- ^ Dieter Brümmerhoff: Finance. 10th edition. 2011, ISBN 978-3-486-70261-3 , p. 297.

- ↑ Annual report of the Council of Economic Experts 2009/2010, p. 327 ff. ( Online ( memento of the original dated November 25, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and remove then this note .; PDF; 455 kB)

- ↑ Michael Hartmann: The myth of performance elites. on: campus.de

- ↑ Review of Michael Hartmann: The Myth of the Performance Elites. on: deutschlandfunk.de

- ↑ Repairing the insurance on the ladder . In: The Economist . February 9, 2013.

- ↑ Serge Halimi: The real scandal: Social inequality undermines democracy. In: Le Monde Diplomatique

- ↑ Joseph E. Fargione et al: Entrepreneurs, Chance, and the Deterministic Concentration of Wealth.

- ↑ Statistical properties of financial time series. at: quantaddict.wordpress.com

- ↑ A crisis of the century every three to four years? on: morningstar.de

- ↑ [statmath.wu-wien.ac.at/courses/mmwi-finmath/Aufbaukurs/handouts/handout-10-Stochastisches_Modell_fuer_Aktienkurse.pdf] (Lecture notes Uni Vienna, Stochastic model for share prices)

- ↑ Annual report of the Council of Economic Experts 2009/2010, p. 330 ff. ( Online ( memento of the original dated November 25, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and remove then this note .; PDF; 455 kB)

- ^ AB Atkinson: The Economics of Inequality. Oxford 1975, pp. 5-6.

- ↑ M. Paglin: The measurement and Trend of Inequality, A Basic revision. In: American Economic Review. Vol. 65, No. 4, 1975, pp. 598-609.

- ↑ Real estate (statistical) . In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 4th edition. Volume 7, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1885–1892, p. 864.

- ^ Friedrich-Wilhelm Henning: Handbook of the economic and social history of Germany in the 19th century. Volume 2, 1996, pp. 769-770.