Distribution of wealth in Germany

The distribution of wealth in Germany is synonymous with the distribution of the total net wealth of German citizens consisting of financial assets , land , fixed assets and consumer assets among individuals, households or groups of people in Germany . It is to be distinguished from the distribution of income , but it must be taken into account that a significant part of income itself consists of returns on assets .

While the distribution of wealth in the Federal Republic has become more equal since around the 1950s, wealth inequality has risen sharply in reunified Germany and has remained at a high level in recent years, mainly due to the increase in financial wealth and private insurance. On a scale of the Gini coefficients between 0 (absolute equal distribution) and 1 (absolute uneven distribution), the distribution of wealth in Germany in 2012 was a Gini coefficient of around 0.78. The federal government's report on poverty and wealth published in March 2013 also found a very uneven distribution.

Germany has one of the highest inequalities within the euro area. The study of the distribution of wealth by the DIW in 2014, based on socio-economic panel data, found the highest inequality of wealth for Germany among the countries of the euro zone. In an international comparison, Germany shows high inequality of wealth.

Development of the distribution of wealth since the end of the 19th century.

The concentration of wealth in Germany fell sharply until around the middle of the 20th century. In 1895 the richest 1% of the population still had almost 50% of the wealth, in 2020 this quota fell to less than 25%. In particular in the interwar period and the period of the economic miracle, the wealth spread narrowed. In the medium and short term, however, the development of asset prices determines the distribution of assets. As a result of the strong increase in equity and, above all, real estate values, the wealth of both the 10% and 50% of the wealthiest, adjusted for inflation, doubled from around 1993 to 2020, while the low wealth of the lower half (without taking pension entitlements into account) hardly changed .

In Germany, a modern wealth tax was introduced for the first time in 1893 with the Prussian Supplementary Tax Act. According to this, the wealth share of the richest 1% was initially around 47%, then rose to around 49%, and from 1909 onwards it fell to just under 46%. The First World War and the subsequent hyperinflation led to a reduction in wealth inequality. After the end of inflation, the richest 1% of the population still had just under 42% of the wealth. The effects of inflation were unspecific. The tangible assets (which most of the assets of the wealthy group) were not affected by inflation, the relative gains in property value owners were but by taxes such as rent tax skimmed off partially. The distribution of wealth in the Weimar Republic initially remained stable. However, with the global economic crisis , share prices and the prices of real assets collapsed. Accordingly, the share of the wealth of the richest 1% collapsed from 1930 to 1934 to 35%. The distribution of wealth during the Nazi era was shaped by the murder and expropriation of the Jews. A large number of Jews had been wealthy before the Nazi era. Their expropriation technically reduced the concentration of assets accordingly. The Second World War , the loss of the eastern territories of the German Reich and the Burden Equalization Act radically changed the distribution of wealth. In the war, property in particular was destroyed, property in the East (and also in the Soviet Zone ) was lost. This hit the wealthy in particular, especially property owners. In burden sharing, 50% of the assets were redistributed. In 1953, the share of the richest 1% had fallen to below 25%. In the context of the economic miracle, the prices of real assets rose massively. The distribution of wealth also became more unequal again and reached a local maximum in 1960 with over 32% of the top 1%. The stagflation then led to the mid-1970s to a real value of the loss property and a period of weakness at the exchanges and a decrease in the proportion of the top 1% to below 20%. By 1990 the share of the richest 1% rose again to almost 25% in line with the real increase in asset prices. The German reunification brought together two economic areas whose wealth distribution was extremely different. Statistically, in 1993 the richest 1% had a share of less than 20%. This rose again to just under 25% by 2020.

Development of the distribution of wealth from 1973 to 1998 (West Germany)

| group | group | 1973 | 1983 | 1988 | 1993 | 1998 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Richest fifth | Richest tenth | 78.0% | 70.1% | 48.8% | 45.5% | 40.8% | 41.9% |

| second richest tenth | 21.3% | 21.9% | 20.2% | 21.1% | |||

| second richest fifth | 3rd tenths | 13.5% | 23.5% | 14.5% | 15.1% | 15.1% | 15.2% |

| 4th tenths | 9.0% | 9.6% | 11.2% | 10.7% | |||

| 3rd fifth | 5th tenths | 5.7% | 5.5% | 4.0% | 5.0% | 7.1% | 6.5% |

| 6th tenths | 1.5% | 2.4% | 3.3% | 3.0% | |||

| 4th fifth | 7th tenths | 2.0% | 1.1% | 0.7% | 1.2% | 1.6% | 1.3% |

| 8th tenths | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.7% | 0.6% | |||

| poorest fifth | 9th tenths | 0.8% | -0.2 % | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.1% |

| poorest tenth | -0.3 % | -0.8 % | -0.3 % | -0.4 % | |||

| Gini index | 0.748 | 0.701 | 0.668 | 0.622 | 0.640 | ||

In 2003, the economist Richard Hauser stated that the analysis of wealth distribution in Germany was insufficient for a long time:

“The personal distribution of [...] assets in Germany has been a research field that has been neglected for many years. […] So far, there is no comprehensive and detailed national wealth account from which the entire wealth attributable to the household sector could be taken. The existing estimates […] differ widely. The statistics on the personal distribution of wealth attributable to the household sector are even more incomplete than the income statistics. The [...] derived results can therefore only provide an incomplete picture [...]. "

In addition to the data basis, methodological differences also make comparison difficult. Most studies do not include pension entitlements in the examined wealth due to lack of data or problematic comparability. For 1973, Mierheimer / Hoher also took into account the pension entitlement assets for the assets examined and subsequently came up with a Gini index of 0.5403; Without including the pension entitlement, as in the table, the Gini index was 0.748.

Between 1973 and 1998, the numbers came from slightly different studies. Therefore, there is no complete comparability between the figures in this period. The apparent decrease in inequality between 1973 and 1998 is questionable in Hauser's view. Because in the years 1988, 1993 and 1998 the company assets are not included, which are not represented in the form of shares traded on the stock exchange. As a result, the actual inequality is likely to be underestimated. The corresponding corporate assets in private hands that are not in the form of shares in 1995 amounted to around DM 1,500 billion.

The distribution of wealth from 2002 to 2007

SOEP as a data basis

More detailed studies on the distribution of wealth are available on the basis of the Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) , a representative longitudinal study classified as excellent. Various problems make it difficult to investigate the distribution of wealth - for example the statistical problem of recording wealthy people in a survey. Since 2002 there has been an additional sub-sample “high-income households” in the SOEP. As a result, the quality of the analyzes of wealth distribution (and income distribution) in Germany has risen sharply since the survey year 2002 compared to earlier data sets. Another advantage of the longitudinal section survey SOEP is the possibility of comparing data. In the SOEP, the years 2002 and 2007 were intensively examined with regard to the distribution of wealth.

Determination of net assets

The SOEP the DIW distinguishes the following asset components: real estate holdings , including real estate, financial assets, including securities, assets from private insurance including home savings contracts, business assets, including forest ownership, property, assets and debts.

The private net wealth examined in the SOEP consists of the following parts:

- Tangible assets

- Basic assets

- Utility (including jewelry, works of art)

- Financial assets (also claims against the state, companies, financial institutions, foreign countries)

- Equity investments (shares, property rights in companies or financial institutions at home and abroad)

After deducting all types of liabilities (e.g. mortgages, consumer loans), this results in total private net assets.

Pension entitlements, a very common form of assets, cannot be methodologically recorded in a population survey and are not included in the assets considered by the SOEP. Because of its widespread use, consideration in the examined wealth would result in a lower Gini coefficient. In addition to the often missing data, the problem of correctly assessing the current value of future pension payments (e.g. due to different life expectancies, discount rates, lack of portability and tradability) speaks against equating it with other types of assets and thus against inclusion in the examined assets.

The total wealth

In 2007 the total net wealth of people in private households, as defined in this way, was 6,100 billion euros. Later analyzes of the same dataset, which take into account the fact that top wealth is difficult to measure, assumed total private wealth for 2007 of 7,225 billion euros.

In 2017, the total assets were around 14,300 billion euros.

Overview of wealth distribution 2002–2007

The following table and graphic (based on SOEP data ) shows the distribution of wealth in 2002 and 2007, for which the population is divided into tenths of a percent, i.e. the richest 10%, the second richest 10%, etc. up to the poorest 10%, respectively form one of ten groups:

The Gini coefficient as a measure of wealth distribution increased from 0.777 in 2002 to 0.799 in 2007. 0 means a complete equal distribution (all people have the same amount) and 1 the greatest possible unequal distribution (one person owns everything, all others nothing). The main part of this increase was recorded by the increase in financial assets and assets in the form of private insurance. About half of the German citizens had no assets and lived directly on their income.

The table above shows a strong concentration of wealth. According to this analysis of the data (2009), the richest 5% of the population owned 46% of total private wealth in 2007, the richest percent owned 23%. In the opinion of Grabka and Frick, the concentration of wealth is actually likely to be even greater, as it is very unlikely that the 100 richest households in Germany were included in the SOEP study . Correspondingly, further studies that take special account of top assets come to greater asset concentrations.

Further investigations

Investigation by DIW for 2012

According to the DIW study based on SOEP data published in 2014 , Germany had the highest inequality of wealth within the euro zone in 2012 . On average, every German owned 83,000 euros, while the median wealth was just under 17,000 euros. The richest percent owned almost 800,000 euros or more. One of the richest 10% belonged to a net worth of EUR 216,000 or more. The average of these richest 10% had a net worth of 639,000 euros. 27.6% had nothing or had more debts than wealth. The Gini coefficient for wealth inequality was 0.78 - this did not, however, include top wealth. The biggest difference to previous years was the wealth of the unemployed: in 2002 they had an average of 30,000 euros, in 2012 an average of 18,000 euros. This decrease is mainly attributed to the Hartz reforms . Due to the limited amount of data available on particularly high wealth, the DIW assumes that the real wealth inequality is very likely to be significantly greater than was recorded in the study.

Investigations by DIW for 2017

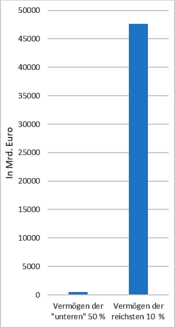

The poor half of the population owned 1.3% of total wealth in 2017, and the richest 10% 56%.

Research that takes into account top wealth

| Persons from 17 |

Fortune 2007 | in % |

|---|---|---|

| poorer 50% | 103 billion euros | 1.4% |

| 6-9 tenth | 2,310 billion euros | 32.0% |

| total | 7.225 billion euros | 100.0% |

| Top 10% | 4,813 billion euros | 66.6% |

| Top 7.5% | 4,408 billion euros | 61.0% |

| Top 2.5% | 3,227 billion euros | 44.7% |

| Top 1% | 2,590 billion euros | 35.8% |

| Top 0.5% | 2.252 billion euros | 31.2% |

| Top 0.1% | 1,627 billion euros | 22.5% |

| Gini coefficient | 0.81 | |

| households | Fortune 2007 | in % |

| Top 0.001% | 419 billion euros | 5.28% |

| Top 0.0001% | 132 billion euros | 1.67% |

The calculations of the DIW (2011) based on SOEP data with additional data on particularly high wealth (which are usually not recorded in the SOEP) from 2007 resulted in the values according to the table for the wealth concentration of people aged 17 and over. According to this, the top 10% owned two thirds of total wealth in 2007, the richest 0.1% (fewer than 70,000 people) owned almost a quarter of total wealth, which is around 16 times as much as half of people aged 17 and over (around 35,000 .000). The top 0.5% (around 350,000 people) together owned roughly as much wealth as the bottom 90% (around 63,000,000 people). According to this calculation by DIW, the Gini index for 2007 is 0.8097.

For 2012, there were only a few observations on particularly large wealth, so that the DIW corrected values on inequality in 2015 by adding external data. According to the calculations of the DIW on the basis of the SOEP data with the addition of the particularly large wealth, in 2012 the richest percent in Germany owned 31–34% of total wealth. The share of the richest 0.1 percent of households was between 14 and 16 percent.

According to an analysis at household level, in 2008 0.001%, i.e. 380 households, had a net wealth of 419.3 billion euros or 5.28% of the net wealth of private households. The richest 0.0001% of households (38 households) owned 132.35 billion euros or 1.67% of total private wealth. A comparable concentration of wealth can also be demonstrated for other countries. For example, in the US, the richest 100 Americans (about 0.00005% of the population ) owned about 1.9% of total wealth in 2006 and the richest 1% of households owned about 34.6% in 2007 (Gini coefficient of 0.83) .

In 2019 too, DIW estimates, which supplemented missing data from the Federal Statistical Office, showed a strong concentration of wealth. According to this, the richest 10% of Germans owned at least 63% of the national wealth.

Studies that include pensions and pension entitlements as assets

A study by the German Institute for Economic Research in 2010 included pensions and pension entitlements (statutory, collective bargaining and private) in the distribution of assets, which until then was mostly not done for methodological reasons. The authors saw a disregard of these entitlements as an important weak point so far. Regarding the informative value of the inclusion of these entitlements, however, they also pointed out that these claims to old-age pension assets are essentially fictitious because, in contrast to existing assets, they cannot be invested and the level of the policy can be changed.

According to the calculations, the total pension entitlements based on 2007 amounted to around 4,600 billion euros, an average of 67,000 euros per adult. In this overall view, civil servants and retirees did well above average. As a result, the inclusion of pension entitlements in the concept of wealth, according to the data collected from the SOEP , meant that the difference between median wealth (middle class) and higher wealth in the 90th percentile (upper middle class / lower upper class) was significantly reduced to 4.4. The authors came to the conclusion that the pension entitlement assets are much less unevenly distributed than the monetary, non-cash and participation assets. According to the authors, this weakens inequality, but the high inequality of wealth remains overall and was assessed as blatant by the authors.

In the international comparison

Since there are different measures for uneven distribution, comparisons can be made for the different measures.

Gini coefficient

With a Gini coefficient of 0.816, the distribution of wealth in Germany is comparable to Saudi Arabia (0.81) and Haiti (0.82). Germany ranks 110th out of 131 countries recorded.

Share of the top 1% in national wealth

The richest percent of the population in Germany has 30 percent of the wealth. By contrast, in Great Britain the richest percent of the population has 24 percent of the wealth, in Italy and France 22 percent each.

Ratio of average to average per capita wealth

If the ratio of average to mean per capita wealth is used as a measure of the inequality, the Global Wealth Report 2019 shows that Germany ranks 164th out of 171 countries worldwide.

Coefficient of variation with increased wealth

For a study on behalf of the EU Commission , not only assets, but so-called augmented wealth , i.e. H. Net wealth plus pension entitlements are taken into account and compared using half the squared coefficient of variation . According to this, Germany took 11th place in a comparison of 15 European countries in terms of inequality.

Origin of wealth and distribution of wealth

Wealth can either be self-acquired or inherited. A study by the Free University of Berlin with the Panel Private Households and Their Finances (PHF) based on survey data distinguishes between the poorer half , middle class (51st to 89th percentile ), middle upper class (91st to 99th percentile) and upper class (100th percentile ). The study looked at the cumulative inheritances up to the beginning of 2015.

In the middle class and middle upper class defined in this way , about 1/3 of the wealth is inherited and 2/3 acquired (this share is relatively constant for the percentiles in the upper middle). In the poorer half , the proportion of heirs is significantly lower, at 17 percent. Inheritance plays the largest role in wealth for the middle class compared to other forms of wealth. Nevertheless, the authors do not see inheritance among the poorer half and the middle class as a dominant cause of wealth accumulation.

The data from the PHF panel were not representative for the upper class , the top percentile (from around 2.5 million euros in net worth) (the highest wealth in the PHF is 75 million euros), also because the basis for data and Investigations are missing. The scientists therefore supplemented the data from other property studies. With the help of statistical comparisons from better researched countries, the authors come to the conclusion that the share of inherited wealth in the upper class is around 4/5 of net wealth.

According to a survey by the Bundesbank on the wealth situation in households in 2014, the composition of net wealth also differs, although data on the top percentile in particular are also missing from this study. According to this, wealthier households more often own real estate, and the difference is even clearer when it comes to company ownership: shareholdings and more generally company ownership are significantly more common in the richer 20% and 10% of households, respectively.

According to Michael Hartmann , the concentration of wealth in Germany is due to the high number of family businesses and their benefits under the inheritance tax law of 2009. The beneficiaries are not, as has often been shown, larger craftsmen's businesses, but large and very large companies. In contrast to other countries in Germany, around half of the 100 largest companies are family-owned. (The managing director of the Association of Family Entrepreneurs, who was referred to in Manager Magazin as the "chief lobbyist of the rich", made a similar statement insofar as, according to him, in the case of family entrepreneurs, business assets on the balance sheet are often indistinguishable from the assets of rich people.) The Inheritance Tax Act According to Hartmann, which was hardly changed by a 2016 reform, enables large corporate assets to be bequeathed almost tax-free. Hartmann refers to statistics according to which the inheritance tax in companies, the higher the smaller the inherited wealth.

Policy measures that affect the distribution of wealth

Historically, the discussion about the distribution of wealth in Germany focused on the inequality of land ownership. In addition to the discussion about land reform in Germany , the question of the expropriation of princes also played a role during the Weimar Republic .

The first legal expression of the demands was found in the 1919 Weimar Constitution with the provision on the social liability of property (Art. 153 Para. 3 WRV), which was also adopted in a slightly modified form in 1949 in the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany ( Art. 14 Para. 2 GG). However, due to the property guarantee laid down in the same article , the possibilities of the rule of law to influence the distribution of wealth are less than with the distribution of income . The welfare state principle anchored in Art. 20 and Art. 28 GG imposes certain obligations on state action, the scope of which is interpreted differently depending on the political point of view.

Within these obligations and legal limits, property policy played an important role in the first decades of the Federal Republic. After the extensive destruction of financial assets in the Zero Hour the new beginning and the currency reform in 1948 first led to offset the burdens of war in the foreground, from 1952 mainly through the bombed and displaced persons were compensated. Thereafter, a number of measures have been taken to encourage workers to build up wealth, thereby making the distribution of wealth more even.

In the concept of the social market economy formulated by Economics Minister Ludwig Erhard , the state promotion of private wealth creation also plays an important role because it is seen as functional to maintain the competitive order. In the law on the formation of the council of experts for the assessment of macroeconomic development of 1963, the council of the five wise men was therefore obliged to examine “the formation and distribution of income and assets”.

Important measures included a. the first capital formation law (1961), the promotion of employee shares and the issue of people's shares . In the area of collective bargaining policy , various models of investment wages have been implemented. Measures to promote housing (7b depreciation, housing bonus , home ownership allowance , child benefit , etc. ) should raise the home ownership rate , which is traditionally low in Germany , and thus also help to change the distribution of wealth. After the successful reconstruction and the economic miracle , the classic instruments to burden the wealthy again gained greater importance: the inheritance tax and the wealth tax . The wealth tax was uniformly regulated in Germany in 1923; the wealth tax law was last amended in 1974. However, after a constitutional court ruling from 1995, the collection of wealth tax was suspended from the 1997 tax year.

In Stabilization Act of 1967 not a distribution destination was included, but was in the following years, the demand for extension of the repeated magic quadrangle charged to the goal of a balanced wealth distribution. Today there is a broad consensus among the parties in the Bundestag about the value of a fair distribution of wealth for the development of the economy and society, although naturally there are different ideas about what is perceived as such and by what means it should possibly be achieved. However, many tried-and-tested instruments for promoting wealth creation have been scaled back since reunification , as other priorities were in the foreground due to the costs of German unity and the ecological restructuring of the market economy .

According to Stefan Josten, in developed economies with unevenly distributed incomes and assets, the formation of human capital can be impaired to an extent that is undesirable in terms of growth and efficiency. Nevertheless, a negative growth effect of inequality should not be equated with a positive growth effect of state redistribution. Only at a control rate below a "growth-maximum" value state redistribution is adapted to increase the economic growth, so Josten.

In November 2007 the DIW suggested:

"Against the background of the increasing importance of property income and the highly unequal distribution of wealth, the reform of inheritance and gift taxes should be reconsidered, as the tax rates are low by international standards and the tax exemptions are already very extensive."

In addition, against the background of wealth distribution in Germany, it makes sense to charge large assets with a wealth tax or a wealth tax for millionaires, according to studies by DIW (2010/2011) (on behalf of the Greens ). The purpose of these taxes or levies - as in the context of the Burdens Equalization Act of 1952 - was to better distribute the burdens of the financial crisis and the resulting national debt in Germany .

See also

- List of countries by total wealth

- List of countries by wealth distribution

- List of countries by wealth per capita

- Distribution of income in Germany

literature

- Richard Hauser : The development of income and wealth distribution in Germany, an overview . (PDF) Information on spatial development, issue 3 / 4.2003

- Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka: Increased wealth inequality in Germany (PDF; 276 kB). In: DIW Berlin weekly report No. 4/2009

- Markus M. Grabka, Christian Westermeier: Persistently high wealth inequality in Germany (PDF) In: DIW, weekly report 9/2014, pp. 151–164

- Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka, Richard Hauser: The distribution of wealth in Germany - Empirical analyzes for people and households , foreword by Sir Anthony Atkinson (research from the Hans Böckler Foundation, vol. 118). Berlin 2010.

- Final report to the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs: “Update of reporting on the distribution of income and assets in Germany” . (PDF) Institute for Applied Economic Research , Tübingen 2011.

Web links

- Distribution of wealth information from the Federal Agency for Civic Education (2009)

- Distribution of wealth: Republic of the have-nots Handelsblatt dated December 4, 2007

Footnotes

- ↑ a b MACROFINANCE LAB BONN. Retrieved June 10, 2020 (American English).

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka: Increased wealth inequality in Germany . (PDF; 276 kB) In: DIW Berlin weekly report , No. 4/2009, p. 54.

- ^ Markus M. Grabka, Christian Westermeier: Persistently high wealth inequality in Germany . In: DIW Berlin weekly report , No. 9/2014, p. 164.

- ↑ The Fourth Report on Poverty and Wealth of the Federal Government (PDF) Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, p. 343 (p. 400 in PDF)

- ↑ Data on wealth only after Cyprus was saved . Article by Stefan Ruhkamp on faz.net , March 11, 2013.

- ↑ DIW boss Fratzscher: "The social market economy no longer exists". In: SPIEGEL ONLINE. Retrieved March 17, 2016 .

- ^ Germany - a divided country . Markus Sievers, Frankfurter Rundschau , February 26, 2014.

- ^ Markus M. Grabka, Christian Westermeier: Persistently high wealth inequality in Germany . In: DIW Berlin weekly report , No. 9/2014, p. 164.

- ^ Moritz Schularick, Charlotte Bartels, Thilo NH Albers: The Distribution of Wealth in Germany, 1895–2018, 2020, digitized

- ↑ Richard Hauser : The development of the distribution of income and wealth in Germany, an overview ( Memento from February 8, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Information on spatial development, issue 2/4.2003, p. 111; 119.

- ↑ Similarly, seven years later, Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka, Richard Hauser: The distribution of wealth in Germany - empirical analyzes for people and households , foreword by Sir Anthony Atkinson (research from the Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, vol. 118 ). Berlin 2010, p. 13: “In view of this multifaceted significance of wealth, it is therefore rather surprising that the current state of research on wealth distribution accounting for Germany is characterized by a rather limited database and a […] only a small number of relevant analyzes based on the The basis of microeconomic data is available over a longer period of time. "

- ↑ The Handelsblatt stated in 2007: Unfortunately, there are no studies for the past like the one recently published by DIW. Richard Hauser from the University of Frankfurt tried to close the existing gaps with estimates ...

- ↑ The official sample of income and expenditure does not contain this data, and larger scientific surveys such as the SOEP do not collect this aspect. See Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka: Increased wealth inequality in Germany (PDF; 276 kB). In: DIW Berlin weekly report , No. 4/2009, p. 60, footnote 12.

- ↑ Rolf-Jürgen Hober / Horst Mierheim: The importance of supply assets for the personal distribution of assets in private households in the FRG 1973 . In: Yearbooks for Economics and Statistics , Issue 5, 1981 page 404.

- ↑ Numbers (1983): H. Schlomann, wealth distribution and private old-age provision, Frankfurt / M. / New York 1992, pp. 136-139; 1988-1998. R. Hauser / H. Stein: The distribution of wealth in the united Germany. The personal distribution of assets . Tübingen, pp. 58-59 .; The net wealth of households is not delimited in the same way in the individual studies, which are all based on the income and consumption samples, as individual asset categories were recorded differently (Hauser, p. 120).

- ↑ Richard Hauser : The development of income and wealth distribution in Germany, an overview ( Memento from February 8, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Information on spatial development, issue 2 / 4.2003, p. 120.

- ↑ Richard Hauser : The development of income and wealth distribution in Germany, an overview ( Memento from February 8, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Information on spatial development, issue 2 / 4.2003, p. 123, note 35; Cf. Stefan Bach / Bernd Bartholmai: Distribution of productive wealth among private households and people. Research report , ed. from the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, Bonn 2002, pp. 18–20.

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka: Increased wealth inequality in Germany . (PDF; 276 kB). In: DIW Berlin weekly report , No. 4/2009, p. 58 f.

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka: Increased wealth inequality in Germany . (PDF; 276 kB). In: DIW Berlin weekly report , No. 4/2009.

- ↑ Federal Agency for Civic Education: Distribution of Assets | bpb. Retrieved December 9, 2018 .

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka: Increased wealth inequality in Germany . (PDF; 276 kB). In: DIW Berlin weekly report , No. 4/2009, p. 56.

- ↑ When interpreting these results, it should also be taken into account that the analysis of financial and tangible assets presented here does not take into account any claims to the social security institutions (GRV, miners' unions, professional pension funds, pension funds, etc.) and neither in the SOEP nor the official Income and expenditure sample (EVS) are not collected. While current pension payments are recorded as an income stream by default, future pension payments are excluded from the analyzes due to the assumptions required to calculate a present value (differential life expectancy, discount rate, etc.) as well as the lack of transferability and tradability. Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka: Increased wealth inequality in Germany . (PDF; 276 kB). In: DIW Berlin weekly report , No. 4/2009, p. 60, footnote 12.

- ↑ The distribution of wealth in Germany - empirical analyzes for people and households . Berlin 2010, p. 53.

- ↑ Stefan Bach, Martin Beznoska, Viktor Steiner: A Wealth Tax on the rich to bring down public debt? Revenue and Distributional Effects of a Capital Levy . (PDF; 246 kB), DIW 2011, p. 10.

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka: Increased wealth inequality in Germany (PDF; 276 kB). In: DIW Berlin weekly report No. 4/2009, p. 59.

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka: Increased wealth inequality in Germany . (PDF; 276 kB). In: DIW Berlin weekly report , No. 4/2009, p. 57.

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka: Increased wealth inequality in Germany . (PDF; 276 kB). In: DIW Berlin weekly report , No. 4/2009, p. 54.

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka, Richard Hauser: The distribution of wealth in Germany - empirical analyzes for people and households (research from the Hans Böckler Foundation, volume 118). Berlin 2010.

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka: Increased wealth inequality in Germany . (PDF; 276 kB) In: DIW Berlin weekly report , No. 4/2009, p. 59.

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka, Richard Hauser: The distribution of wealth in Germany - empirical analyzes for people and households . Berlin 2010, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Persistently high wealth inequality in Germany (PDF) Markus M. Grabka, Christian Westermeier, in DIW weekly report No. 9.2014, pp. 151–164.

- ↑ The wealth gap in Germany: the poor stay poor, the rich get richer. sueddeutsche.de, February 26, 2014, accessed on February 28, 2014 .

- ↑ Germany has the greatest wealth inequality in the euro zone. Handelsblatt, February 26, 2014, accessed on February 28, 2014 .

- ↑ Great statistical uncertainty regarding the share of the top wealthy in Germany (PDF) DIW weekly report No. 7.2015, p. 132

- ↑ New study on wealth distribution: Always more for a few . In: The daily newspaper: taz . October 2, 2019, ISSN 0931-9085 ( taz.de [accessed on May 11, 2020]).

- ↑ a b Stefan Bach, Martin Beznoska, Viktor Steiner: A Wealth Tax on the Rich to Bring down Public Debt? (PDF; 246 kB), DIW 2011, p. 11.

- ↑ a b Stefan Bach, Martin Beznoska, Viktor Steiner: A Wealth Tax on the Rich to Bring down Public Debt? DIW 2011: Given the modest size of the high-income sample and the fact that the very rich are underrepresented in household surveys, household wealth at the top of the distribution cannot be accurately estimated on the basis of SOEP data alone. The SOEP records 75 persons who report net wealth of at least Euro 2 million, and 20 persons reporting at least Euro 5 million. While the reported net wealth of the richest person in the SOEP was less than Euro 50 million in 2007, it is well known that a substantial number of persons or families living in Germany have wealth exceeding this amount by a large margin. According to the yearly ranking of the 300 richest Germans published by the business periodical manager magazin (2007), the minimum amount of net wealth required to make it on this list was about Euro 350 million in 2007. We estimate the wealth distribution at the very top on the basis of this source and adjust the wealth distribution derived from the SOEP accordingly. , Pp. 8-9; Details on the methodology cf. P. 9.

- ↑ a b Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka, Richard Hauser: The distribution of wealth in Germany - empirical analyzes for people and households . Berlin 2010, p. 56. Numbers there according to Klaus Boldt: The 300 richest Germans . In: Manager Magazin Spezial , October 2008, pp. 12–57. and after: Wojciech Kopczuk , Emmanuel Saez : Top Wealth Shares in the United States: 1916-2000: Evidence from Estate Tax Returns . (PDF; 1.0 MB), in: National Tax Journal , 2004, 57, pp. 445–488.

- ↑ Great statistical uncertainty regarding the proportion of the top wealthy in Germany (PDF) DIW weekly report No. 7.2015, pp. 130–131

- ^ Edward N. Woolf: The Asset Price Meltdown and the Wealth of the Middle Class . (PDF; 220 kB) New York University, 2012, p. 58.

- ↑ Ulrike Herrmann: The fortune of millionaires: Hidden wealth . In: The daily newspaper: taz . December 18, 2019, ISSN 0931-9085 ( taz.de [accessed on May 11, 2020]).

- ↑ a b c Old-age pension assets dampen inequality . (PDF) German Institute for Economic Research , January 18, 2010; Retrieved December 6, 2015

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka, Richard Hauser: The distribution of wealth in Germany - empirical analyzes for people and households . Berlin 2010, p. 166. Abstract for conclusion ( Memento from December 30, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Anthony Shorrocks, Jim Davies, Rodrigo Lluberas: Global wealth report 2019 . In: Credit Suisse Research Institute (ed.): Global wealth reports . October 2019 (English, credit-suisse.com [PDF]).

- ↑ Anthony Shorrocks, Jim Davies, Rodrigo Lluberas: Global wealth report 2019 . In: Credit Suisse Research Institute (ed.): Global wealth reports . October 2019, p. 48 (English, credit-suisse.com [PDF] "Wealth inequality is higher in Germany than in other major West European nations ... We estimate the share of the top 1% of adults in total wealth to be 30%, which is Also high compared with Italy and France, where it is 22% in both cases. As a further comparison, the United Kingdom ['s] ... share of the top 1% is 24%. ").

- ↑ Kristina Antonia Schäfer: Global Wealth Report 2019: The Prosperity Illusion. Retrieved June 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Lawrence Mishel, Josh Bivens, Elise Gould, Heidi Shierholz: The State of Working America . Cornell University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-8014-6622-9 ( google.de [accessed May 12, 2020]).

- ↑ Eva Sierminska, Márton Medgyesi: The distribution of wealth between house holds, Research note 11/2013 . Ed .: European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion. December 2013 ( europa.eu ).

- ↑ Timm Bönke, Giacomo Corneo, Christian Westermeier: Inheritance and personal contribution in the assets of the Germans: A distribution analysis, April 2015 . ( Memento of April 19, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF) p. 16

- ↑ Lena Schipper: You have to work hard for your fortune - at least in Germany . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung , April 19, 2015, p. 18

- ^ Timm Bönke, Giacomo Corneo, Christian Westermeier: Inheritance and personal contribution in the assets of the Germans: A distribution analysis . April 2015, p. 30 and pp. 33–34.

- ^ Timm Bönke, Giacomo Corneo, Christian Westermeier: Inheritance and personal contribution in the assets of the Germans: A distribution analysis . April 2015, p. 30 and p. 34.

- ↑ Wealth and finances of private households in Germany: Results of the 2014 wealth survey , Deutsche Bundesbank Monthly Report March 2016, p. 72.

- ↑ a b Lea Fauth: Elite researcher on wealth: “Billions inherited tax-free” . In: The daily newspaper: taz . July 16, 2020, ISSN 0931-9085 ( taz.de [accessed July 28, 2020]).

- ↑ Lukas Heiny, manager magazin: Wealth tax: How the rich influence politics - manager magazin - companies. Retrieved July 28, 2020 .

- ↑ § 2, Law on the formation of the Expert Council for the Assessment of Overall Economic Development of August 14, 1963.

- ↑ Stefan Josten, Inequality, State Redistribution and Overall Economic Growth , Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8305-1377-3 , pages 252, 253

- ↑ Stefan Josten, Inequality, State Redistribution and Overall Economic Growth , pp. 176–177

- ↑ Press release of November 7, 2007

- ↑ Stefan Bach, Martin Beznoska, Viktor Steiner: A Wealth Tax on the rich to bring down public debt? Revenue and Distributional Effects of a Capital Levy (PDF; 246 kB), DIW 2011.

- ↑ Stefan Bach, Martin Beznoska, Viktor Steiner: occurrence and distributional effects of a green property tax . (PDF; 1.1 MB), DIW 2010