Alliance 90 / The Greens

| Alliance 90 / The Greens | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| party leader |

Ricarda Lang Women's Policy Spokesperson Omid Nouripour (subject to postal vote confirmation) |

| general secretary |

Emily May Büning Political Secretary |

| vice-chairman |

Pegah Edalatian-Schahriari Spokesperson for Diversity European and International Coordinator Heiko Knopf |

| Federal Managing Director | Emily May Büning Organizational Federal Manager |

| Federal Treasurer | Marc Urbatsch |

| founding | January 13, 1980 (The Greens) September 21, 1991 (Alliance 90) May 14, 1993 (Association) |

| place of incorporation |

Karlsruhe (The Greens) Potsdam (Alliance 90) Leipzig (Association) |

| Headquarters | Square in front of the New Gate 1 10115 Berlin |

| youth organization | green youth |

| newspaper | Green Magazine |

| Party-affiliated foundation | Heinrich Böll Foundation |

| alignment |

Green Politics Left Liberalism European Federalism |

| Colours) | green ( HKS 60) |

| Bundestag seats |

118/736 |

| seats in state legislatures |

290/1884 |

| Government grants | €25,622,757.67 (2020) |

| number of members | 125,126 (as of December 2021) |

| minimum age | none |

| average age | 48 years (as of December 31, 2019) |

| proportion of women | 41% (as of December 31, 2019) |

| International connections | Global Greens |

| MEPs |

21/96 |

| European party | European Green Party (EGP) |

| EP Group | The Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA) |

| site | gruene.de |

Bündnis 90/Die Grünen ( abbreviation : Greens ; also known as Bündnisgrüne , B'90/Grüne , B'90/Die Grünen or Die Grünen ) is a political party in Germany . One main focus is environmental policy . The guiding principle of "green politics" is ecological , economic and social sustainability .

In West Germany and West Berlin comes the 12./13. The Greens party , founded in Karlsruhe on January 1, 1980, of the anti-nuclear and environmental movements , the new social movements , the peace movement and the New Left of the 1970s. In the federal elections of 1983 , the Greens managed to get into the Bundestag and from 1985 to 1987, in a red-green coalition in Hesse, they provided Joschka Fischer as a state minister for the first time. After reunification , the West German Greens fell through the five percent hurdle in the 1990 federal election .

Two other lines of development go back to the citizens' movement in the GDR . Alliance 90 was formed by the Peace and Human Rights Initiative , Democracy Now and the New Forum founded during the political upheavals in autumn 1989 . In the 1990 Bundestag elections , this moved into the Bundestag as a parliamentary group together with the Green Party in the GDR , which was founded at the turn of the year 1989/1990 , the Independent Women's Association and the United Left . After the Green Party in the GDR had already merged with the West German Greens immediately after this election, which meant that the Greens were represented by two East German MPs in the Bundestag, the Greens were not united with Alliance 90 until May 14, 1993. The fourth line of development was the Alternative List for Democracy and Environmental Protection (AL) , founded on October 5, 1978 , which, as an independent party, took on the tasks of a state association of the Greens under its own name from 1980 and also merged with Bündnis 90 on May 14, 1993.

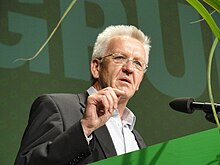

After returning to the Bundestag as a parliamentary group in 1994, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen were part of the federal government for the first time from 1998 to 2005 in a red-green coalition . From 2005 to 2021, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen were again the opposition party in the Bundestag, before the Greens entered into a traffic light coalition with the SPD and FDP at federal level in 2021. In the 2021 federal election , the party achieved the best national result in its history with a vote share of 14.8%, and in the 2019 European election Bündnis 90/Die Grünen achieved the best international result in its history with 20.5%. In May 2011, Winfried Kretschmann was the first prime minister in Baden-Württemberg , who, after a green-red government, has been in charge of a green-black state government since 2016 . In addition, the Greens are involved at state level in a red-green government in Hamburg and in a Jamaica coalition in Schleswig-Holstein . In Hesse , the Greens form a black-green coalition together with the CDU . Since 2014, the Greens have governed Thuringia with the Left Party and the SPD for the first time in a red-red-green coalition under Prime Minister Bodo Ramelow (Die Linke). In addition, the Greens have been part of the government in a traffic light coalition in Rhineland-Palatinate since 2016. Another red-red-green coalition has governed Berlin since December 2016, but under SPD leadership; in Bremen since the 2019 election as well. In Saxony and Brandenburg, the party has been involved in Kenya coalitions since 2019 . Overall, the party is currently represented in 15 out of 16 state parliaments and participates in 10 out of 16 state governments .

Content profile

Programmatic Development

The Greens are considered a “program party”. Since their founding, they have made a change from radical ecological and pacifist demands to a more pragmatic content orientation. This development did not take place continuously, especially in the first few years. While the programs were initially characterized by conceptual innovation and a discursive style of argumentation, they became radicalized verbally and in terms of content around 1986, before consolidating again from 1990.

Appearing as a "fundamental alternative" to all established parties, the Greens emphasized their character as ecological , social , grassroots democracy and non-violent in their first party program from 1980 . The social and economic policy demands clearly bore the Marxist signature of the eco-socialists who had defected from the K groups to the Greens . These include the " realos " Winfried Kretschmann , Ralf Fücks , Krista Sager (all Communist League West Germany ) or Jürgen Trittin ( Communist League ). For a long time, bitter arguments between “ Fundis ” and the pragmatically oriented “Realos” determined the struggle for the basic content of the Greens.

After German reunification , the failure of the West German Greens to pass the five percent hurdle in the 1990 federal elections , and the Greens' unification with the GDR citizens' movement in Alliance 90 in 1993, Alliance 90/The Greens repositioned themselves. An intermediate step in the programmatic development was the so-called “Basic Consensus” of 1993, in which the West German Greens and Alliance 90 had formulated their common basic political convictions as the basis for their merger and which since then has preceded the party statutes. The ecological and foreign policy demands were geared more closely to the possibilities of the social market economy and the changed realities of international politics after the end of the East-West conflict . In the course of this process, the party was on the brink of splitting several times. In 1990/91, numerous prominent representatives of the left wing left the party, which accelerated the programmatic change. During the red-green coalition from 1998 to 2005, there were renewed crucial tests in view of Germany's military operations in Kosovo and the war in Afghanistan , the compromise on the nuclear phase-out and the Hartz IV reforms. After 2005, the Greens focused more on their ecological core issue and in 2008 they decided on the Green New Deal , a concept that should rebalance the relationship between ecology and economy and promote ecological modernization .

Today's policy and election programs

"... to respect and to protect... - change creates stability" is the title of the current basic program of Bündnis 90/Die Grünen. It was decided by a large majority at the first purely digital party conference of the Greens in November 2020. It replaces the old basic program that was decided at a federal delegates ' conference in Berlin in March 2002 and in turn replaced the federal program from 1980.

As in 2002, the current basic program states: “The focus of our policy is on people in their dignity and freedom.” It is expressly emphasized that the basic value of ecology is derived from this: “Protecting and preserving the environment is a prerequisite for a life in dignity and freedom.” In general, the program has the following five basic values: ecology, justice, self-determination, democracy and peace.

According to the foreword, the fourth basic program in the history of BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN marks “the entry into a new phase of the party: It defines an alliance party that makes an offer to society in its entirety.” The main differences to the earlier basic program are in terms of content in the rejection of referendums at federal level (so-called "citizens' councils" are being demanded instead), the unconditional basic income as the "guiding principle" of social security and the commitment to a "federal republic of Europe" as a long-term perspective.

While the idea of sustainability is conservative at its core , the Greens stand for left-liberal and communitarian concepts and positions in socio-political terms. Examples of this are the multicultural society the Greens are aiming for, the integration of immigrants , lesbian and gay policy , in particular the commitment to equality in civil partnerships and the opening up of marriage , as well as the positions on data protection , the information society and civil rights . The Greens' concept of justice emphasizes intergenerational justice in addition to distribution , opportunities , gender and international justice .

The election program for the 2013 federal election entitled “Time for green change” was accepted in April 2013 with no dissenting votes and one abstention. It marked a clear shift to the left by the party. The Greens based their demand for higher taxes for high earners less on social redistribution requirements than on a universal sustainability law.

In a membership decision in June 2013, the party members selected the nine most important key projects from the election program that should be given priority in coalition negotiations. In the area of "environment and energy", the party base gave top priority to the goal of completely converting the power supply to renewable energies by 2030. This was followed by calls for an end to factory farming and a redefinition of prosperity indicators that should no longer be based solely on economic growth . Party members from the "Justice" area voted for the introduction of minimum wages , followed by the abolition of private health insurance in favor of citizen insurance for all and a reorganization of the financial markets . Limiting arms exports was identified as the most important project from the topic of "modern society" , followed by the abolition of childcare allowances in favor of expanding daycare places and systematically promoting programs against right- wing extremism . The tax plans, which were discussed particularly controversially in the media after the party congress, were not chosen by the members as one of the core demands. The demand for the introduction of a wealth levy came in fourth place, and the demand for low taxes for low-income earners and the middle class in fifth place in the area of justice. Compared to the election of the top candidates, in which 62% of party members took part, turnout in the membership decision was significantly lower at 26.7% of party members.

Protection of the environment and nature, energy, transport

The core idea of green politics is sustainable development . The idea of environmental protection therefore runs through large parts of the program of Bündnis 90/Die Grünen. In particular, the economic, energy and transport policy requirements are closely interrelated with environmental policy considerations. Climate protection policy is at the center of all considerations .

Right from the start, the green program focused on the immediate halt to the construction and operation of all nuclear power plants , the promotion of alternative energies and a comprehensive energy -saving program. After the Chernobyl catastrophe in 1986, the Green demands became more radical and realpolitik compromises were rejected. With the reorientation after 1990, the party returned to a more dovish program, and concerns about global warming and the ozone hole somewhat eclipsed those about nuclear energy. Many Greens found the numerous compromises made during the red-green government from 1998 to 2005 disappointing.

The goals of the energy transition formulated in the program for the 2013 federal elections were above all the phase-out of coal -fired energy and a complete power supply from renewable energies by 2030. By 2040, heat generation and transport should also be largely converted to renewable energies. An increase in electricity prices was to be prevented by withdrawing the special regulations for electricity-intensive companies , and job-creating effects in the field of renewable energies were also expected.

A similarly high priority is given to transport policy . Utopian resolutions, such as the demand made at the Magdeburg party conference in 1998 to raise the price of petrol to five DM through a corresponding tax, are no longer to be found in today's programs. In the run-up to the Bundestag elections, this decision had led to considerable losses in polls, as it was perceived as an expression of a return by the potential governing party to the fundamentalism of previous years.

According to the ideas of Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, the speed limit should be 80 on country roads and 120 on motorways . The proportion of bicycle traffic is to be increased to more than 20% by 2020. The party calls for a traffic turnaround . Furthermore, the Greens often criticize the construction of high-speed routes .

One of the specific demands in the 2013 election campaign was to designate 10% of public forests as protected areas. In the election program for the 2017 Bundestag elections , the Greens are calling for only zero-emission new cars to be permitted from 2030 onwards. In addition, they provide a mobile pass with which local public transport, car sharing and bike sharing can be booked centrally.

business

For a long time, the basic economic policy demands of the Greens were critical of capitalism and, according to some authors, also Marxist in orientation. The causes of the ecological problems were essentially located in the production conditions and in the consumer behavior of the capitalist economic system. However, pragmatic, non-Marxist approaches, such as ecologically justified infrastructure investments, energy taxes or saving and recycling techniques, were added to the classic socialist proposed solutions such as the unbundling of large corporations early on . After the party redefined its positions in the early 1990s, pronounced socialist economic demands have largely disappeared from the Greens' program in favor of liberal demands.

The basic program of 2002 calls for further development of the economic system into an eco-social market economy (referred to here as "ecological-social market economy"). The aim is "that our society agrees on long-term goals for an economic policy that sets clear ecological framework conditions for the market" and advocates an "ecological further development of our tax and financial system". One of the principles of an ecological and social market economy is that "the profits of the individual may not be achieved at the expense of society". A "strengthening of society" is demanded and in doing so, one sets oneself apart from "state-socialist, conservative and free-market political models". Globalization , at least in its actual current form, is described negatively, which is characterized by environmental destruction, an increasing division of the world population into rich and poor, and privatized, commercialized, and terrorist violence.

The central demands of the Greens in the 2013 federal election campaign included a debt brake for banks and a cap on bonuses for managers.

In the immediate climate protection program published in summer 2019, the Greens are calling for CO 2 pricing that reflects the costs of climate damage. This should go hand in hand with the abolition of the electricity tax. The proceeds are to be paid back in full to the citizens as a climate bonus.

“Those who protect the climate pay in less than they get out and have made a profit at the end of the year. Anyone who damages the climate pays for it. This also applies to companies. This increases the incentive to switch to climate-friendly technologies and to invest in renewable energies and efficiency.”

In the basic program of 2020, one again commits to an eco-social market economy (now called "social-ecological market economy") and emphasizes: "The economy serves the people and the common good, not the other way around." Here, "markets [...] could be a powerful instrument for economic efficiency, innovation and technological progress.”

Social, family, education

In family policy, the Greens have long been calling for the abolition of spouse splitting and “modern individual taxation”. The previous regulations are no longer up to date: "It promotes marriages and not families." Furthermore, the rapid, massive financial expansion of kindergarten places nationwide was required.

In the 2013 election program, a nationwide minimum wage of EUR 8.50 or more was planned, with equal pay for temporary workers and permanent staff. The Hartz IV standard rate for long-term unemployed should be raised to 420 euros, sanction rules for benefit recipients should be relaxed and initially suspended. It should no longer be possible to limit employment contracts without a material reason, and mini-jobs should be curbed by the fact that social security contributions should apply from as little as 100 euros.

The Greens wanted to introduce a guaranteed pension of 850 euros a month for those who have been in the labor market for 30 years or who have taken care of children. The Greens stuck to the pension at 67, but wanted to cushion it with a partial pension and easier access to full disability pensions . Citizen insurance for everyone should replace the current system of private and statutory health insurance . Rent increases should be more strictly limited for new leases or modernizations.

According to the goals formulated in the program for the 2013 Bundestag elections, one billion euros more should be invested annually in universities and 200 million euros in adult student loans . Childcare allowance should be abolished.

In the case of soft drugs such as cannabis, the Greens want to decriminalize personal use and private cultivation and, taking into account the protection of minors, allow them to be sold legally through licensed specialist shops. The medical use of and research into drugs should no longer be hindered. The unequal treatment of cannabis and alcohol by driving license law should also be ended. Cannabis offenses unrelated to road traffic should then no longer be sent to the driver's license office unsolicited and without the consent of the person concerned.

Bless you

The Greens wish to make precaution the guiding principle of health policy. The players in the healthcare system should be better networked, especially through better digitization .

They demand more support for patients in the event of treatment errors and greater appreciation of the nursing profession, which is characterized not only by appropriate pay but also by improved working conditions.

Funding is to be provided by a citizens' insurance scheme, and the health authorities are to be strengthened. In rural areas, there is a wish for additional health and care centers.

Corona policy

- Compulsory vaccinations: As part of the current federal government, the Greens have decided to make vaccinations compulsory for health and nursing staff from March 15, 2022

- Corona vaccine must be available to everyone worldwide, a global vaccine campaign is needed, and the WHO must be strengthened for this.

- With the financial support of companies and corporations in the context of the pandemic , they must be converted to climate neutrality at the same time .

Gender, lesbian and gay politics

Topics such as gender mainstreaming or equal pay between the sexes were already extensively anchored in the federal program of the Greens in 1982. The party has advocated a legal quota for women on supervisory boards and executive boards since 2013 .

Since a party congress resolution in November 2015 , gender-equitable language has been mandatory in all party resolutions; as a rule, the gender asterisk should be used because it does not discriminate against intersex and transgender people ( details ).

In 2017, the Greens welcomed the opening up of marriage to same-sex couples ( Marriage for All ).

For the 2021 federal election , the Greens’ election program calls for a women’s quota of 33% for the executive boards of listed companies and 40% for the supervisory boards. For companies owned or with participation by the federal government, the quota of women should be 50%, as well as in the diplomatic service of the Federal Republic. "Voluntary regulations have brought nothing," explains the election program. In order to reduce the gender pay gap , the Greens want to introduce an equal pay law, including the right to bring legal action for women's associations. The "outdated transsexual law" must be replaced by a self-determination law.

consumer protection, nutrition and agriculture

When Minister Renate Künast took office in 2001, the previous Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Forestry was renamed the Federal Ministry of Consumer Protection, Food and Agriculture . This should make it clear that consumer protection is a high priority . Among other things, the organic seal was introduced in September 2001 , which is used to mark products that come from at least 95% organic farming. The agricultural turnaround with a regionally anchored and ecological agriculture is given a similarly high priority as the energy turnaround.

One of the central concerns in the 2013 federal election campaign was the abolition of subsidies for factory farming . The election program also called for a significant improvement in the situation of animals in agriculture and a reduction in the number of animals kept overall through various measures. These include a heavily revised animal welfare law and clear bans on serious interventions such as castration of piglets without anesthetic , docking of tails or beaks and grinding of teeth.

Further program points are protection against excessive overdraft interest and the right to your own checking account .

Civil rights, democratic participation, internet politics

Civil rights take up a lot of space in the programme. The Greens oppose centralized and untargeted mass surveillance, any restriction of freedom of assembly , and any form of weakening or undermining rule-of- law standards in criminal law or criminal proceedings. In contradiction to these principles was, among other things, the approval of the Greens for the so-called anti-terror laws and the aviation security law during the red-green coalition.

Bündnis 90/Die Grünen unreservedly endorses the basic individual right to asylum and sees immigration in general as a productive force. For this reason, the isolation of Europe as an island of prosperity against the growing global migration flows is rejected .

In the 2013 election campaign, the Greens called for the abolition of informants for the protection of the constitution . The voting age should be lowered to 16.

In internet policy , the Greens strictly reject any restriction of freedom on the internet. A free Internet for everyone, financed by a company fund, was called for in the 2013 federal election program.

military operations and arms exports

One of the key characteristics of the Greens in their early years was their strong roots in the peace movement . In the 1980s, the Greens opposed Germany's NATO membership. In the federal program of 1980, the Greens called for the immediate dissolution of the military blocs in the west and east. Many Green members took part in protests against the storage of US nuclear weapons on German soil . Petra Kelly was one of the key activists against nuclear weapons .

This position changed in the course of the 1990s. In June 1992, Daniel Cohn-Bendit called for military action in Sarajevo . Particularly under the impression of the Srebrenica massacre in 1995, after Joschka Fischer had become German Foreign Minister in 1998 , Germany took part in the Kosovo War and the war in Afghanistan . The federal delegates' conference in Bielefeld on May 13, 1999 (see also Joschka Fischer's speech on the NATO mission in Kosovo ) led to the resignation of the pacifist wing of the Greens.

As the governing party, the Greens supported the Bundeswehr's deployment in Afghanistan . On November 16, 2001, Chancellor Gerhard Schröder put the vote of confidence in the Bundestag.

With the basic program of 2002, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen bid farewell to strict pacifism and no longer categorically ruled out violence against genocide and terrorism , which is legitimate under international law.

One of the most important items on the agenda for the 2013 federal election was the legal limitation on arms exports .

In June 2013, during the civil war in Syria , the Greens refused to supply arms to the rebels. In October 2014, the leader of the Greens parliamentary group in the Bundestag, Katrin Göring-Eckardt, announced that her parliamentary group would support a deployment of the Bundeswehr against IS , even if this meant deploying ground troops. On December 4, 2015, the majority of the faction rejected the approval of the Bundeswehr's combat mission in Syria because, among other things, it had not been clarified how the relationship with President Bashar al-Assad should be shaped.

foreign policy and European policy

The Greens are committed to a strong Europe and a common foreign and security policy in Europe. They criticize Erdoğan's role in Turkey and demand that Turkey 's accession negotiations with the EU be put on hold. In the basic program of 2002, the European Union is described as the most far-reaching approach to a responsible community of states, but is too fixated on a neoliberal economic policy. In their 2013 federal election program, the Greens campaigned for a more democratic Europe and a refugee policy based on solidarity. In the fight against the euro and financial crisis , budget consolidation is to be supplemented by stronger financial market regulation and a European debt redemption fund.

taxes and finances

For more than twenty years, starting in 1980, under the heading “Taxes, Currency and Finances” it was characteristically said that “This part of the program is still being revised”, but considerations on the financing of the Green demands now occupy a large part of the Greens’ program. The Greens consider the expansion of the eco-tax introduced under the red-green federal government to be the most important incentive tax in order to be able to solve ecological problems within the framework of the market economy according to the polluter -pays principle .

For the 2013 federal elections, the Greens presented plans to finance the desired social change through additional burdens for top earners and the wealthy. The additional income should flow into a better infrastructure for education and childcare, into the ecological restructuring of society and into debt reduction . Recipients of a taxable income of up to around 60,000 euros should be relieved by increasing the basic allowance from 8130 euros to 8712 euros.

Specifically, the Greens called for a temporary wealth tax of 1.5% on assets of one million euros or more, which is to be replaced after ten years by a permanent wealth tax . The wealth levy should bring the budget 100 billion euros to reduce the national debt in ten years. The top tax rate should be raised from 42 to 49% from a gross income of 80,000 euros. The Greens wanted to melt away the marriage splitting and replace it with individual taxation, in which the tax-free subsistence level can be transferred to the partner. For existing marriages, the splitting benefit should initially be capped so that only households with an income of 60,000 euros or more would be charged. In principle, income from capital should again be taxed at the same rate as income from work, so the current withholding tax should be dropped. Flat-rate taxes such as company car taxation , the tax benefits for hoteliers, for example, or the exemptions from the eco-tax should be phased out, and the motor vehicle tax should be amended in favor of electric and hybrid cars . There are also plans to double inheritance tax revenue . In addition, a blacklist in the fight against tax havens in Europe and sanctions against banks and states that do not stop such practices should help in the fight against tax evasion and tax evasion .

party structure

members

| Membership numbers since 1982 | |

|---|---|

| 1982 | 22,000 |

| 1984 | 31,078 |

| 1986 | 38,170 |

| 1988 | 40,768 |

| 1990 | 41,316 |

| 1992 | 36,320 |

| 1994 | 43,899 |

| 1996 | 48,034 |

| 1998 | 51,812 |

| 2000 | 46,631 |

| 2002 | 43,881 |

| 2004 | 44,322 |

| 2006 | 44,677 |

| 2008 | 45,089 |

| 2010 | 52,991 |

| 2012 | 59,653 |

| 2014 | 61,369 |

| 2016 | 61,596 |

| 2017 | 65,257 |

| 2018 | 75,311 |

| 2019 | 96,487 |

| 2020 | 107,307 |

| 2021 | 125.126 |

The composition of the members of Bündnis 90/Die Grünen has changed several times in the course of its history. After it was founded, conservative forces left the party and turned to the ÖDP from 1982 . Between 1990 and 1992, many eco-socialists left the party. During this period, the number of members fell by 6,000 to just over 35,000, but the number of resigned members was higher, since a significant number of new members joined the party in the same period, who obviously agreed with the prevailing realpolitik orientation.

In East Germany, after the union of Alliance 90 with the Greens in 1992/93, the number of members jumped from a good 1,000 to around 3,000, but dropped to a good 2,500 after 1998. The proportion of the East German state associations was consistently 6 to 7% of the total number of members of the party. By 1998, the total number of members had risen to almost 52,000. The compromises with the SPD and, above all, Germany's participation in the war under the red-green government resulted in a slump in membership numbers. Since Bündnis 90/Die Grünen have been in opposition, the number of members has increased again and roughly doubled in the 2010s. The largest increase of 21,000 new members was recorded in 2019. Since April 2020, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen have been one of four German parties with more than 100,000 members, alongside the Union parties and the SPD.

In West Germany, the majority of active party members were recruited from the age cohort of those born between 1954 and 1965, i.e. from a “post -1968 movement ”. For this reason, the Greens were long regarded as a "generational party", so that a "greying" of the party was predicted. However, this prediction was not confirmed. Although the Greens are no longer the youth party they were considered to be in the 1980s and to some extent still in the 1990s, the Green Alliance members have the lowest average age at 48 years and the party has the lowest proportion of pensioners at 13% of all parties represented in the Bundestag. With an average age of 46.6 years in 2009, the parliamentary group was the youngest in parliament. In the current 19th Bundestag, the parliamentary group of the Greens is, on average, the second youngest after that of the FDP .

At 40.5%, the proportion of women among the Greens is higher than that of the other parties represented in the Bundestag. Bündnis 90/Die Grünen achieved the highest value of all parties in terms of the proportion of members with a university degree. This is 68%. The proportion of non- denominational people is also high at 42% . It is only significantly higher for the Left Party at 79%.

Among the professions represented by the Greens, the strong presence of civil servants and employees in the public sector is striking, with 45% of all working members being more represented than all other professional groups. From this derives the criticism that "the protest officials". It is sometimes seen as problematic that the majority of members today not only have a high level of formal education, but also earn significantly more than the average (while two-thirds were still unemployed in 1983), so that there is a risk that social problems will be perceived differently.

electorate

Freiburg with 21.2%, Berlin-Friedrichshain – Kreuzberg – Prenzlauer Berg Ost (20.4%) and Stuttgart I (19.6%)

In party research , there is the thesis that the Greens and their electorate are the result of a change in values and are post-materialist because of wealth and education . The conflict between ecology and economy has partially or even largely suppressed the left - right opposition. Nevertheless, most Green Party voters describe themselves as "left", especially since the party was strongly influenced by the new social movements of the 1970s. However, after many eco-socialists and “ fundis ” left the party in 1990/91 and the establishment of the Left Party , the Greens lost part of the left-wing electorate. Participation in government at the federal level and the associated joint responsibility for the German military operations in Kosovo and Afghanistan and for the Hartz IV reforms also contributed to the fact that about half of the electorate has changed over the years. In this context, there is talk of a "bourgeoisification" of the Greens. This process is also progressing with the aging of the age cohort that has shaped the Green Party since its inception. Despite this, the Greens achieved their best result among the under-30s in the 2009 federal elections.

Green voters are considered to have an above-average education (62% have a high school diploma or advanced technical college entrance qualification ), have an above-average net household income (EUR 2,317) and are relatively young (38.1 years on average). In the 2009 federal election, they did well above average with 15.4% among first- time voters , while among voters over 60 they were far below the overall result at 5%. Since the 1990s, the Greens have attracted new groups of voters and have had a strong following among the up-and-coming young voters. Women vote Green more often than men. In the 2009 federal election, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen won 13% of female voters compared to 9% of male voters. Service occupations are particularly well represented among green voters . While civil servants made up the largest proportion of Green voters, at 18% in the 2009 federal election, the self -employed , who accounted for just 1% in 1987, had risen to 14%, making them the second largest group of voters.

The Greens find their voters primarily in urban milieus with a high level of education. In the three city states of Berlin, Hamburg and Bremen, for example, the party usually achieves double-digit election results and has been involved in state governments there several times. However, the Greens also have strongholds in some non-city states, particularly in Baden-Württemberg and Hesse, and more recently in Schleswig-Holstein and parts of Lower Saxony and Bavaria. In the university towns of Freiburg im Breisgau , Constance , Tübingen and Darmstadt , the party provided or provides the mayors . Since January 2013, Stuttgart has been the first state capital to be governed by a green mayor. In the Berlin constituency of Kreuzberg-Friedrichshain-Prenzlauer Berg Ost , Hans-Christian Ströbele was able to win a direct mandate for the Bundestag four times in a row . On the other hand, the party has a lower percentage of votes in rural areas.

The position of Bündnis 90/Die Grünen in the eastern federal states is problematic . In 1990, the Alliance 90 and the East Greens were still relatively successful here and were involved in a traffic light coalition in Brandenburg . The merits of the civil rights movement and thus of Alliance 90 no longer played a significant role soon after reunification. In the “ super election year ” of 1994, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen fell through the five percent hurdle in all eastern German states except Saxony-Anhalt. This fate befell the state association in Saxony-Anhalt four years later. In the following years, the results in state elections were sometimes below 2%. In the sparsely populated Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen had never been able to clear the five percent hurdle before the state elections on September 4, 2011. In the state elections in Saxony in 2004 and those in Thuringia and Brandenburg in 2009 , it narrowly managed to re-enter some East German state parliaments. In the 2009 federal election , the party also increased its share of the vote in the east by 1.6 percentage points to 6.0% (compared to 11.4% in the west, each time excluding Berlin), so that the character of a “west party” seems to be gradually weakening . Nevertheless, in East Germany there is largely no milieu for a firm social anchoring, which provides the main voters of the Greens in West Germany .

In the 2009 federal election, voter migration by previous SPD voters brought the Greens an increase of 870,000 votes, while Bündnis 90/Die Grünen lost 140,000 voters to the Left Party and a further 30,000 votes to the group of non-voters . The migration of voters to and from the bourgeois camp was significantly lower . While 50,000 previous Union voters switched to the Greens, the party lost 30,000 voters to the FDP. In the 2005 federal election, the Greens had gained 140,000 votes from the SPD, but 240,000 voters switched to the Left Party and 70,000 votes to the non-voter camp. In contrast to 2009, 130,000 votes were lost to the Union in 2005. In the 2019 European elections, the party mainly won votes from the CDU and SPD, but compared to the 2017 federal election.

Women's statute, separation of office and mandate

Bündnis 90/Die Grünen have committed themselves to a women's statute. This provides for a women's quota for list places , delegates and speaking rights. At least half of the seats are reserved for women in elections to equal offices and in the preparation of electoral lists. In a body with three seats, at least two women must be elected. If there is no candidate for a place that is reserved for women, the women present can release it for an open election. Because of the quota system, most spokespersons or chairmen in the federal and state associations, in the parliamentary groups and other bodies are double-headed. The Greens consider the women's quota to be necessary until a balanced ratio of men and women in politics is achieved in order to achieve equal participation of women in politics. Other privileges for female party members are the "women's vote" and the "women's veto". At the request of at least ten women who are entitled to vote (at the federal level) or by one individual (up to and including the state level), a vote must be carried out among the women present before a regular vote. At all meetings, the majority of the women present can exercise a veto right to postpone a proposed resolution to the following meeting. A right of veto can only be exercised once per submission.

For the Greens in the 1980s, grassroots democracy was not only a demand from society as a whole, but should also be exemplified within the “anti-party party”. As a "fundamental alternative to the conventional parties", which of course had to comply with the requirements of the party law, their political representatives should always be bound to the will of the decentrally organized party base and be subject to constant control. One wanted to prevent a functionary caste of professional politicians, as criticized by the Greens in all established parties. One of the rigid preventive measures against bureaucratic inflexibility in a political class was that in the early years all party offices had to be held on an honorary basis. Another element to prevent professionalized parliamentary elites was that a large part of the allowances had to be paid to the party and only an amount equivalent to a skilled worker 's salary could be kept personally. In addition, there were no chairpersons in any of the committees, but rather a board of speakers. Until 1990/91, the party and the parliamentary group each had three spokespersons with equal rights, who were replaced by others after a short time. Consequently, the Greens did not conduct any personalized election campaigns for a long time, for which external consultants and advertising agencies have only been commissioned since the beginning of 2000. In order to avoid an accumulation of offices and a concentration of power, the Greens pursued a strict separation of office and mandate for a long time . In 2003, however, this regulation was relaxed, since then no more than a third of the members of the federal executive board may also be members of parliament, but they may not be members of a state or federal government. At the Green Party Congress in January 2018, an eight-month transitional period was introduced, with a majority of 77% exceeding the required two-thirds majority, during which members of the government can continue to hold office despite the election as Green Party leader. This affected the Federal Chairman Robert Habeck, who had been in office since January 2018 and who had to resign from the office of Schleswig-Holstein Environment Minister after the transition period at the end of August 2018 . Since 1987, members of the Federal Executive Board have been able to apply for remuneration.

Of the numerous special features that differentiated the Greens from the established parties in terms of organization in their founding phase, only the dual leadership, the greatly relaxed separation of office and mandate and the women's quota remain today. The SPD adopted the latter in a milder form in 1988, while the CDU introduced a so-called women's quorum in 1994 . In many areas, the Greens have become more professional and aligned with other parties.

outline

| national association | Spokesperson/Chairman | members |

|---|---|---|

| Baden-Wuerttemberg | Sandra Detzer , Oliver Hildenbrand | 14,040 |

| Bavaria | Eva Lettenbauer , Thomas von Sarnowski | 18,600 |

| Berlin | Susanne Mertens , Philmon Ghirmai | 10,469 |

| Brandenburg | Julia Schmidt , Alexandra Pichl | 1,979 |

| Bremen | Alexandra Werwath , Florian Pfeffer | 1,037 |

| Hamburg | Maryam Blumenthal | 2,200 |

| Hesse | Sigrid Erfurth , Philip Kraemer | 8.229 |

| Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania | Weike Bandlow , Ole Krueger | 1,000 |

| Lower Saxony | Hans-Joachim Janssen , Anne Kura | 11,000 |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | Mona Neubaur , Felix Banaszak | 23,000 |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | Jutta Paulus , Josef Winkler | 5,000 |

| Saarland | vacant | 1,728 |

| Saxony | Christin Furtenbacher , Norman Volger | 3,060 |

| Saxony-Anhalt | Susan Sziborra-Seidlitz , Britta-Heide Garben | 1,200 |

| Schleswig Holstein | Ann-Kathrin Tranziska , Steffen Regis | 5,000 |

| Thuringia | Ann-Sophie Bohm-Eisenbrandt , Bernhard Stengele | 1,200 |

The party is organized into 16 state associations as well as around 1,800 local associations and around 440 district associations. In large cities, there are sometimes local groups for individual parts of the city and district groups for city districts. According to the principle of decentralization , the local branches are granted extensive autonomy. Overseas chapters exist in Brussels and in Washington, DC

The strongest state associations are those of North Rhine-Westphalia, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, the smallest are the state associations in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt. Measured against the number of inhabitants, the city-states of Berlin, Hamburg and Bremen have associations with a large number of members.

Federal Delegates Conference

The Federal Delegates' Conference (BDK) or Federal Assembly is the supreme decision-making body and corresponds to the federal party congress of other parties. The delegates elect the federal board, the candidates on the European election list, the members of the party council, the federal arbitration court and the federal auditors and decide on the program and statutes.

The Federal Delegates' Conference takes place at least once a year. Depending on its size, each district association sends at least one delegate to the Federal Assembly. When the Greens merged with Alliance 90, the East German state associations were granted special rights. They are entitled to 185 of the 840 delegate places.

Federal Board

The day-to-day business of the federal party is carried out by the federal executive board, which consists of an equal dual chairmanship ( Annalena Baerbock and Robert Habeck ), the political director ( Michael Kellner ), the federal treasurer ( Marc Urbatsch ) and two deputy chairmen, the European and international coordinator Jamila Schäfer and spokeswoman for women's policy Ricarda Lang .

The six-member federal board is elected by the federal delegates' conference for two years. Since 2001, the two equal party leaders have been called federal chairmen, previously there was talk of spokespersons. Until 1991, the party executive in the west was headed by a group of three, whose appointments took into account not only the quota of women but also the representation of the various currents within the party.

The then chairmen of the board, Claudia Roth and Fritz Kuhn , did not stand for re-election to the board in December 2002 after the federal delegates' conference had narrowly rejected a motion to abolish the separation of office and mandate. However, Claudia Roth was re-elected in October 2004 in the election to the Federal Board of Directors in Kiel. This was possible because a ballot on this problem had relaxed the previously strict regulation and now one third of the members of the federal executive board can also be members of the Bundestag.

political management

Instead of a general secretary , there is a political director in the federal association and in some state associations. He works full-time for the party, is a voting member of the board and is elected directly by the delegates' conference. Previous political directors were Eberhard Walde (1983-1991), Heide Rühle (1993-1998), Reinhard Bütikofer (1998-2002), Steffi Lemke (2002-2013) and Michael Kellner (since 2013).

The federal association and some regional associations also have an organizational management. Organizational managing directors are employed by the board of directors as employees , are bound by instructions and have no political decision-making authority of their own. The organizational manager of the federal association since August 2012 is the former spokeswoman for the Green Youth, Emily Büning .

Country and Party Council

The supreme decision-making body between the federal assemblies is the regional council, which meets quarterly. It decides on the policy guidelines between the federal delegate conferences and coordinates the work between the bodies of the federal party, the parliamentary groups and the state associations. In fact, its function as a discussion body is more important than that of a decision-making body. The members of the federal executive board belong to the state council by virtue of their office; other members are delegated from the state associations, the parliamentary group, the state parliamentary groups and the European Parliament as well as from the federal working groups. In 1991, the state council replaced the federal main committee.

The advisory party council set up in 1998 has similar tasks . It develops and plans joint initiatives of the committees, parliamentary groups and state associations. The party council usually meets during the session weeks of the German Bundestag. Its members work on the committee on a voluntary basis. The federal chairmen and the political director belong to the party council by virtue of their office. The rest of the up to 16 members are elected by the federal delegates' conference.

G coordination

Due to the many government participations that the Greens have taken in the federal states since 2007, they have become an influential factor in the Bundesrat and in the federal-state votes. The Greens have created the so-called G-Coordination for internal party coordination in federal politics. The leaders of the federal party, the parliamentary group and the government Greens in the federal states coordinate with her. The structure of the G-coordination includes a specialist coordination for selected policy areas, an overarching G-coordination at working level and two fireside chats for top political personnel.

Federal Women's Council, policy commission and working groups

The Federal Women's Council plans and coordinates the women's political work within the party. It includes the female members of the federal executive board, the parliamentary group and the European Parliament, as well as two female delegates from each state association. Between the Federal Assemblies, it decides on the guidelines for women's policy. The members are elected by the women of the state associations and the state working groups on women's policy as well as the federal executive board, the Bundestag and European parliamentary group and the federal working groups on women's and lesbian policy. A federal women's conference is convened annually.

There are federal working groups (BAG) for many policy areas . These flank the programmatic work of the Principles Commission and are intended to develop concepts and strategies on key issues in cooperation with (professional) associations, initiatives and scientific institutions and to coordinate the work within the party. The federal working groups have the right to submit motions to federal assemblies and the state council. The voting members are elected by the respective state working groups (LAG) or delegated by the state executive committees. The federal working groups usually meet two to three times a year.

The following federal working groups have existed since 2016: work, social affairs, health, disability policy, education, Christians, democracy and law, energy, Europe, women's policy, peace, global development, children, youth, family, culture, agriculture and rural development, lesbian policy, media and Network policy, migration and escape, mobility and traffic, ecology, planning, building, living, secular greens, gay policy, animal welfare, business and finance, science, university, technology policy.

Green youth and campus green

The youth association of Bündnis 90/Die Grünen is the Green Youth with 7,100 members (as of October 2017). At the federal level, the youth association was only founded in 1994, at that time still under the name Green Alternative Youth Alliance (GAJB), state associations have existed since 1991. The Green Youth has been a sub-organization of the party since 2001. As such, it has the right to submit motions at party conferences and appoints representatives to party committees. The maximum age for membership is 27 years, it is independent of a party membership. The highest decision-making body is the Federal Congress, to which, in contrast to most other political youth organizations, all members are invited and are entitled to vote. In many areas, the Green Youth positions itself to the left of the parent party.

The more than 70 green and green-related university groups are united in the Federal Association of Green-Alternative University Groups Campusgrün, which is organizationally and politically independent of the party. Among other things, Campusgrün works with the Alliance Green Federal Working Group on Science, University & Technology Policy, with the Green Youth and with the Heinrich Böll Foundation. The individual university groups are autonomous and have different ties to the party. National assemblies of the umbrella organization are held twice a year, at which each member university group is represented by one or two delegates with voting rights.

Heinrich Böll Foundation

Like all other party-affiliated foundations , the Heinrich Böll Foundation is formally independent. Contrary to its name, its legal form is not a foundation , but a registered association . In its current form, it emerged in 1996/97 from the three foundations Buntstift (Göttingen), Frauen-Anstiftung (Hamburg) and Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung (Cologne), which were founded in the first half of the 1980s and formed the Rainbow Foundation was. The various foundations of the green state associations were organized in the colored pencil federation. The Heinrich Böll Foundation is still organized on a federal basis and maintains sixteen state branches. It is represented in 27 foreign offices worldwide. Since 2017, the board has been made up of Barbara Unmüßig and Ellen Ueberschär, the managing director is Livia Cotta.

The Heinrich Böll Foundation is a political education institution and maintains a study program that awards scholarships to students and doctoral candidates. It shares the basic values of ecology , democracy , solidarity and non- violence with the Green Party . Cross-cutting issues that run through the entire work of the foundation are migration and gender democracy . The history of green politics and the new social movements is documented and processed in the Green Memory Archive .

finance

| Revenue of the Greens in 2013 | EUR | portion |

|---|---|---|

| State Funds | 15,056,822.65 | 37.50% |

| membership fees | 8,724,659.32 | 21.73% |

| Mandate contributions and similar regular contributions | 8,988,904.88 | 22.38% |

| Donations from natural persons | 4,283,060.27 | 10.67% |

| Events, distribution of pamphlets and publications and other revenue-related activities | 843,988.05 | 2.10% |

| Donations from legal entities | 697,127.62 | 1.74% |

| income from other assets | 149,890.02 | 0.37% |

| Other revenue | 1,409,040.04 | 3.51% |

| Income from business activities and participations | 1,476.67 | 0.00% |

| total | ≈ 40,154,970 | 100% |

The annual report of the Greens for 2013 showed income of around 40.2 million euros for the entire party. A good 8.2 million euros of this went to the federal association, a good 13.6 million euros to the state associations and around 19.5 million euros to subordinate regional associations. State party funding accounted for the largest share , which is heavily dependent on the number of elections in a year and the success of the party. In 2014, state funds of around 14.8 million euros were set by the German Bundestag. Of this, around 2.3 million euros went to the state associations and around 12.5 million euros to the federal association.

This contrasted with expenditure in 2013 of almost 43.4 million euros. The federal association accounted for a good 10.9 million euros, the state associations for a good 13.6 million euros and the subordinate regional associations for 20.0 million euros. With more than 14.3 million euros (32.89% of expenses), personnel expenses accounted for by far the largest item, alongside expenses for election campaigns of 14.2 million euros (32.73% of expenses). A good 7.8 million euros were spent on general political work and a good 6.6 million euros on material expenses for ongoing business operations.

The positive net worth of the party was 34,771,885 euros. The federal association accounted for almost 40,000 euros, the regional associations almost 14 million euros and the subordinate regional associations around 20.8 million euros.

The financial investor Jochen Wermuth, who has been investing exclusively in "green" companies since 2008, donated a total of 599,989 euros to Bündnis 90/Die Grünen in 2016.

| Donations to Bündnis 90/Die Grünen over €10,000 in 2012 | |

|---|---|

| Association of the metal and electrical industry in Baden-Württemberg | €60,000 |

| BMW AG | €48,535 |

| Daimler AG | €45,000 |

| Association of Bavarians. Metal and electrical industry | €35,000 |

| Metal and Electrical Industry Association NRW | €15,000 |

| alliance | €30,000 |

| IBC Solar AG | €23,500 |

| Ergo | €15,000 |

| Munich Re | €15,000 |

| Chemical Industry Association V | €12,500 |

| total | €299,535 |

| donation amount | dispenser | date of receipt |

|---|---|---|

| 300,000 euros | Jochen Wermuth | February 23, 2016 |

| 299,989 euros | Jochen Wermuth | Aug 29, 2016 |

| 110,000 euros | Südwestmetall – Association of the metal and electrical industry in Baden-Württemberg | December 12, 2016 |

Politics in federal, state, local and EU

parliamentary group

An important power center within the party is the parliamentary group . In the 20th German Bundestag of 2021, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen is represented with 118 MPs as the third largest parliamentary group. The average age is 42 years and 59.3% of the group members are women. The parliamentary group chairmen are Britta Haßelmann and Katharina Dröge , the parliamentary secretary is Irene Mihalic .

The Greens in the Bundestag used to have three spokespersons with equal rights, who changed every year. This changed after the federal elections in 1990, in which Bündnis 90 and the Greens were represented as a group with only eight MPs, with Werner Schulz as spokesman . Since Bündnis 90/Die Grünen re-entered the Bundestag as a parliamentary group in 1994, they have had two chairpersons elected for the entire legislative period.

coalitions at the state level

| Government participation of the Greens, Alliance 90 and Alliance 90/The Greens |

||

|---|---|---|

| length of time | state/federal | coalition partner |

| 1985-1987 | Hesse | SPD ( Cabinet Borner III ) |

| 1989-1990 | Berlin | AL with SPD ( Senate Momper ) |

| 1990-1994 | Lower Saxony | SPD ( Schröder I Cabinet ) |

| 1990-1994 | Brandenburg | B'90 with SPD and FDP ( Cabinet Stolpe I ) |

| 1991-1999 | Hesse | SPD ( Cabinet Acorn I and II ) |

| 1991-1995 | Bremen | SPD and FDP ( Senate Wedemeier III ) |

| 1994-1998 | Saxony-Anhalt | SPD ( Cabinet Höppner I ( tolerated by PDS )) |

| 1995-2005 | North Rhine-Westphalia | SPD ( Cabinet Rau V , Cabinet Clement I and II , Cabinet Steinbrück ) |

| 1996-2005 | Schleswig Holstein | SPD ( Cabinet Simonis II and III ) |

| 1997-2001 | Hamburg | SPD ( Senate round ) |

| 1998-2005 | federal government | SPD ( Schröder I and II cabinet ) |

| 2001-2002 | Berlin | SPD ( Senate Wowereit I (tolerated by PDS)) |

| 2007-2019 | Bremen | SPD ( Böhrnsen II and III Senate , Sieling Senate ) |

| 2008-2010 | Hamburg | CDU ( Beust III Senate and Ahlhaus Senate ) |

| 2009-2012 | Saarland | CDU and FDP ( Müller III cabinet and Kramp-Karrenbauer I cabinet ) |

| 2010-2017 | North Rhine-Westphalia | SPD ( Cabinet Kraft I (as minority government) and II ) |

| 2011-2016 | Baden-Wuerttemberg | SPD ( Cabinet Kretschmann I ) |

| 2011-2016 | Rhineland-Palatinate | SPD ( Cabinet Beck V and Cabinet Dreyer I ) |

| 2012-2017 | Schleswig Holstein | SPD and SSW ( Albig Cabinet ) |

| 2013-2017 | Lower Saxony | SPD ( Cabinet Weil I ) |

| 2014-2020 | Thuringia | Die Linke and SPD ( Cabinet Ramelow I ) |

| 2016-2021 | Saxony-Anhalt | CDU and SPD ( Haseloff II cabinet ) |

| since 2014 | Hesse | CDU ( Cabinet Bouffier II and III ) |

| since 2015 | Hamburg | SPD ( Senate Scholz II , Senate Tschentscher I and II ) |

| since 2016 | Baden-Wuerttemberg | CDU ( Cabinet Kretschmann II and III ) |

| since 2016 | Rhineland-Palatinate | SPD and FDP ( Cabinet Dreyer II and III ) |

| since 2016 | Berlin | SPD and Die Linke ( Senate Müller II and Senate Giffey ) |

| since 2017 | Schleswig Holstein | CDU and FDP ( Günther cabinet ) |

| since 2019 | Bremen | SPD and Die Linke ( Senate Bovenschulte ) |

| since 2019 | Brandenburg | SPD and CDU ( Cabinet Woidke III ) |

| since 2019 | Saxony | CDU and SPD ( Cabinet Kretschmer II ) |

| since 2020 | Thuringia | Die Linke and SPD ( Cabinet Ramelow II ) |

| since 2021 | federal government | SPD and FDP ( Scholz cabinet ) |

The Greens entered into many government alliances at federal and state level with the SPD . Red-Green was considered a political project of the 1968 generation . Government cooperation between the Social Democrats and the Greens appeared to be a realistic option for power when SPD federal chairman Willy Brandt spoke of a “majority on this side of the Union” in the Bonn round after the state elections in Hesse in 1982 . Since then, the left-wing camp has viewed red-green as a project, as a “concrete utopia of post- materialism ”. At the end of the 1980s, the SPD 's Berlin program and its candidate for chancellor , Oskar Lafontaine , clearly converged on green positions. Within the Greens, however, the stance on government participation was the most controversial point of disagreement between the Realos and the Fundis. The party threatened to break up on this question. The first red-green coalition was formed in Hesse between 1985 and 1987. The first government participations in particular were extremely conflictual. In 1990/91 the Realpolitik wing prevailed and red-green state governments became more and more common.

After the end of the red-green federal government in 2005, there were initially hardly any starting points for a revitalization of red-green, for which both the political and the arithmetic prerequisites were missing. All red-green governments were voted out in 2005 and in Berlin, where a government with the Alliance Greens would have been possible in 2006, Klaus Wowereit preferred a coalition with the PDS . It was not until 2007 that the SPD and the Greens formed a government again in Bremen. This was also a grand coalition from 2011 to 2015 , since the SPD and Bündnis 90/Die Grünen were the two largest parliamentary groups. However, the red-green cooperation in the smallest federal state did not serve as a coalition political model. Only in 2010 and 2011 was there a renaissance with the formation of governments in North Rhine-Westphalia, Rhineland-Palatinate and Baden-Württemberg. In the latter federal state, the Greens have had Winfried Kretschmann as prime minister since 2011, initially in a green-red coalition and since 2016 in a green-black coalition.

While government alliances with the SPD are considered “intersection coalitions”, those with the Union are seen as “supplementary coalitions”. Cooperation between the CDU and the Greens depends largely on the top players. While the black-green coalition in Hamburg of the green base in 2008 was primarily due to the person of the metropolitan liberal Ole von Beust , it failed shortly after Christoph Ahlhaus took office in 2010. In Hesse, the Greens were able to participate in the government under the Conservative hardliner Roland Koch as prime minister impossible, even though they were fiercely courted by the Hessian CDU and FDP after the 2008 state elections. In 2014, as a result of the Hessian state elections on September 22, 2013 , a black-green coalition was formed under Koch's successor, Volker Bouffier . It is the first of its kind in a flat country.

The development of the German party landscape into an asymmetrical five -party system had a significant influence on the inner-party discussions about the coalition behavior of the Greens. They play a central role as the “hinge party” between the left and the bourgeois camp. Almost all realistic three-way constellations require Bündnis 90/Die Grünen. Since the 2009 federal election, the Greens have increasingly not committed themselves to coalition statements, even before state elections. In 2018, the Greens governed in nine coalitions and in eight different constellations. Due to the high number of government participations, their influence on federal legislation has grown significantly.

Since December 2014, the first red-red-green coalition , i.e. made up of the Left Party , SPD and Greens, has governed Thuringia under the left-wing politician Bodo Ramelow . It was Bündnis 90/Die Grünen's first government participation in an East German state since 1998. Another red-red-green coalition has existed in Berlin since 2016, here led by SPD politician Michael Müller .

In addition, there were red-green alliances in Saxony-Anhalt (1994 to 1998) and in Berlin (2001 to 2002), which were tolerated by the PDS according to the so-called Magdeburg model . In Hesse, this model failed in 2008 due to resistance from four SPD deputies. In North Rhine-Westphalia, the Kraft I cabinet was a red-green minority government from 2010 to 2012, which, however, did not follow the Magdeburg model but relied on changing majorities and campaigned for approval from the Left Party as well as the CDU and FDP. The government lacked one vote for a majority in the state parliament. In the May 2012 election , the coalition achieved its own majority (→ Kabinett Kraft II ).

A government made up of the SPD, the Greens and the FDP is referred to as a traffic light coalition . From 1990 to 1994 there was a government alliance in Brandenburg similar to a traffic light coalition , in which, however, not the Greens but the then independent Alliance 90 was the coalition partner of the SPD and FDP (→ Cabinet Stolpe I ). The first real traffic light coalition at state level was the Wedemeier III Senate in Bremen (December 1991 to July 1995). FDP party leader Guido Westerwelle has always strictly rejected coalitions, especially with Bündnis 90/Die Grünen. The course of the then FDP was rejected by the then Greens. From 1995 to 2016 there was no traffic light coalition.

It was only after the state elections in Rhineland-Palatinate on March 13, 2016 that a traffic light coalition was formed again. The second Dreyer cabinet was sworn in on May 18, 2016.

A coalition of SPD, Greens and SSW , known as the “ Danish traffic light ”, governed Schleswig-Holstein from 2012 to 2017. Since the 2017 state election, the Greens have been part of the Jamaica coalition there .

From 2009 to 2012, the CDU, FDP and Greens in Saarland formed the first so-called Jamaica coalition ( Cabinet Müller III (Saarland) and Cabinet Kramp-Karrenbauer I ). Prime Minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer resigned from the coalition on January 6, 2012 and brought about early state elections on March 25, 2012 .

From 2016 to 2021 there was the first Kenya coalition of CDU, SPD and Greens at state level in Saxony-Anhalt. There are currently other Kenya coalitions in Brandenburg and Saxony (since 2019).

local politics

After the Hessian local elections in 1981, the first red-green alliances were formed in Kassel and in the Groß-Gerau district , and a traffic light alliance was formed in Marburg . In the mid-1990s, black-green coalitions in several cities in the Ruhr area, which were seen as experiments or models for such in state and federal politics, caused a sensation. Alliances with the CDU followed later, including in Saarbrücken , Kiel , Frankfurt am Main and Hamburg , whose Senate is both the state government and the supreme body for municipal tasks.

The first green mayor in Germany was Elmar Braun in Maselheim in Baden-Württemberg in 1991 . Previously, in May 1990, Hans-Jürgen Zimmermann had been elected mayor of Ludwigslust in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania by the New Forum , and later he became a member of Alliance 90/The Greens. Sepp Daxenberger , who was the first green mayor in Bavaria from 1996 to 2008 in Waging am See and at the same time state chairman of the Bavarian Greens from 2002 , became particularly well known before he became chairman of the state parliamentary group in 2008. As a down-to-earth (organic) farmer, he managed to win a clear majority in the CSU homeland of Upper Bavaria . In Berlin, Monika Herrmann is the district mayor of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg . With Franz Schulz and Elisabeth Ziemer , there were two district mayors in Kreuzberg and Schöneberg for the first time in 1996 .

In total, the party provided around 40 mayors in 2013 , most of them in Hesse, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg. In October 2012, Fritz Kuhn was elected the first green mayor of a state capital in Stuttgart. Green mayors also hold office in the university cities of Bonn ( Katja Dörner ), Freiburg im Breisgau ( Dieter Salomon ), Tübingen ( Boris Palmer ) and Darmstadt ( Jochen Partsch ) as well as in Bad Homburg vor der Höhe ( Michael Korwisi ) . In the runoff elections for the 2014 local elections in Bavaria on March 30, Wolfgang Rzehak in the district of Miesbach and Jens Marco Scherf in the district of Miltenberg were elected district administrators for the first time .

European Parliament and international memberships

At the European level , Bündnis 90/Die Grünen has joined forces with other green parties to form the European Green Party (EGP). Reinhard Bütikofer has been co-chair of the EGP since 2012 . The members of the EGP in the European Parliament belong to the group The Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA). In addition, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen is a member of the Global Greens and the European Movement network .

Daniel Cohn-Bendit was an integration figure of the European Greens. He is a member of both the German and French Greens . Cohn-Bendit has been a member of the European Parliament since 1994. In Germany in 2004, in France in 1999 and in 2009 he was the green top candidate. Since 2002 he was one of the two group leaders, since 2009 together with Rebecca Harms , also from Bündnis 90/Die Grünen.

In the 2014 European elections , Bündnis 90/Die Grünen achieved 10.7% and thus won 11 seats, which form a German delegation within the entire Greens/EFA group. The head of the delegation is Sven Giegold .

From 1999 to 2004 Michaele Schreyer was Commissioner for Budget and for the European Anti-Fraud Office in the Prodi Commission . She was the first and so far only representative of Bündnis 90/Die Grünen in the European Commission .

story

prehistory

The Greens emerged in the Federal Republic of Germany as a merger of a broad spectrum of political and social movements in the 1970s. The founding of the party was largely supported by the ecology , anti-nuclear , peace and women's movements . The political spectrum ranged from the K-groups in the wake of the student movement of the 1960s to conservative environmentalists. Various parties and electoral alliances from the ecology and anti-nuclear movement, such as the Green List for Environmental Protection in Lower Saxony, the Green List for Schleswig-Holstein , the Green Action Future , the Action Group for Independent Germans (AUD) and left-leaning alternative and colorful lists, especially in the big cities. Most of these electoral lists failed at the five percent hurdle, for example in the state elections in Lower Saxony and Bavaria in 1978. In the European elections in 1979 , the other political association Die Grünen, with Petra Kelly and the former CDU member of the Bundestag Herbert Gruhl , ran as the top candidates and achieved 3.2% of votes. The reimbursement of campaign costs of over 4.5 million DM formed the financial basis for the further development of a nationwide party. With 5.1% of the votes, the Bremen Green List (BGL) succeeded in entering a state parliament for the first time in the state elections on October 7, 1979.

Founding of the first state associations in 1979 and the federal party in 1980

On September 30, 1979, a meeting of about 700 supporters of the ecological movement took place in Sindelfingen near Stuttgart , which resulted in the founding of the Greens in Baden-Württemberg as the first state association. In addition, a state association in North Rhine-Westphalia was founded on December 16, 1979 in Hersel near Bonn .

On January 13, 1980, the federal party Die Grünen was founded in Karlsruhe . The first federal program described the Greens as "social, ecological, grassroots democracy, non-violent". The self-image was that of an “anti-party party”.

The founding of the party was accompanied by arguments between the left and the right wing about the programmatic orientation, the composition of the executive board and the possibility of dual membership in the Greens and in a K-group, which was ultimately rejected. Some spokesmen on the right wing of the party, such as Baldur Springmann , Herbert Gruhl , Werner Vogel and August Haussleiter (co-founder of the Action Group of Independent Germans ) were suspected of having racialist ideas, being close to right-wing extremist organizations or having a National Socialist past. Right-wing extremist groups also tried to infiltrate the party in the early days. Above all, the Berlin Greens, which were in competition with the Alternative List (AL) and were almost meaningless, were considered to be extremely right-wing.

With the third party congress in June 1980, the party actually split. The right wing around Herbert Gruhl and Baldur Springmann left the party by 1981 due to the influx of left-wing activists to form the Ecological-Democratic Party (ÖDP), while the influence of the K-groups, especially Group Z , was growing. In 1985, the federal main committee of the Greens decided to dissolve the Berlin state association, whose function was taken over by the AL instead. By the mid-1980s, the eco -fascist tendencies within the Greens had disappeared.

With 1.5% of the votes in the federal elections on October 5, 1980 , the Greens were only able to achieve a disappointing result, but then jumped the five percent hurdle in state elections in Berlin (1981) and Hamburg, Hesse and Lower Saxony (1982).

Establishment in the Bundestag and failure (1983–1990)

In 1983 , the Greens entered the German Bundestag for the first time with 5.6% of the second votes and 27 MPs . Werner Vogel , who was elected on the North Rhine-Westphalian state list, would have been the senior president of the new Bundestag, but did not take up his mandate due to allegations of pedophilia and previous memberships in the NSDAP and SA.

In the years that followed, public perception was primarily determined by the fierce and sometimes chaotic factional struggles between the fundamentalists (“ Fundis ”) and real politicians (“ Realos ”) over the relationship to the social system of the Federal Republic. The main point of contention was whether the Greens should strive for government participation or settle for a strict opposition role. In 1985 the first red-green coalition was formed in Hesse , in which Joschka Fischer was appointed Hessian Minister of the Environment.

In the 1987 federal election , the Greens won 8.3% of the second votes and 44 seats in the German Bundestag. The fall of the Wall in 1989 also proved to be a historic turning point for the West German Greens. In the federal elections of 1990 , the votes were counted in separate electoral areas in the old federal states with the former West Berlin and in the new federal states including East Berlin . The Greens had only enforced this unique special regulation six weeks before the election after a lawsuit before the Federal Constitutional Court - and now it failed. Unlike the other parties represented in the Bundestag, they did not merge with a "sister party" before the election, so the Greens in West Germany and a list of Alliance 90/Greens - a citizens' movement in East Germany - ran separately. For the majority of the Greens, there was no German question before the fall of the Wall . The two-state system was not questioned until the Volkskammer elections in 1990 , and people were skeptical or opposed to reunification . In the federal elections of 1990, the West German Greens advertised accordingly with the slogan “ Everyone is talking about Germany. We're talking about the weather " and failed with the voters. With 4.8% of the votes, they missed entering the Bundestag.

No organizational feature of the Greens has caused as much discussion inside and outside the party as the rotation principle, which was only used for a few years . According to the decision of a federal assembly in 1983, members of parliament had to vacate their mandate halfway through the legislative period for a successor who had previously shared an office with the elected member of parliament. In addition, the parliamentarians were only given an imperative mandate by the party base . In fact, the constitutionally untenable imperative mandate played no role from the outset, and already in the first electoral term after entering the Bundestag there were various problems with the handling of the rotation principle. Petra Kelly and Gert Bastian refused to rotate, while others reluctantly gave up the MP seats to an alleged or actual second guard. Otto Schily only had to resign from the Bundestag in March 1986 because of his prominent work in the Flick investigative committee . As early as 1986, the two-year rotation for members of the Bundestag was replaced by a four-year rotation, which was no longer to play a role at federal level, however, since the Greens were no longer represented in the Bundestag from 1990 to 1994. In 1991 the rotation principle was completely abolished. Other principles of the founding period quickly proved to be unsustainable. So the general public of all party and even the parliamentary group meetings was abolished after a few years.

Foundation of the Green Party and Alliance 90 in the GDR