German Democratic Republic

| German Democratic Republic | |||||

| 1949-1990 | |||||

|

|||||

| Official language |

German Sorbian (in parts of the districts of Dresden and Cottbus ) |

||||

| capital city | Berlin ( East Berlin ) | ||||

| State and form of government | real socialist republic with one-party dictatorship | ||||

| Head of state |

President of the GDR Wilhelm Pieck ( SED , 1949–1960) Chairman of the State Council Walter Ulbricht (SED, 1960–1973) Willi Stoph (SED, 1973–1976) Erich Honecker (SED, 1976–1989) Egon Krenz (SED, 1989) Manfred Gerlach ( LDPD , 1989–1990) President of the People's Chamber (i. V.) Sabine Bergmann-Pohl ( CDU , 1990) |

||||

| Head of government |

Prime Minister of the GDR Otto Grotewohl (SED, 1949–1964) Chairman of the Council of Ministers Willi Stoph (SED, 1964–1973) Horst Sindermann (SED, 1973–1976) Willi Stoph (SED, 1976–1989) Hans Modrow (SED / PDS, 1989 –1990) Prime Minister of the GDR Lothar de Maizière (CDU, 1990) |

||||

| surface | 108,179 km² | ||||

| population | 16.675 million (1988) | ||||

| Population density | 154 inhabitants per km² | ||||

| currency | 1949 Deutsche Mark (DM), renamed in 1964 to Mark of the German Central Bank (MDN), in 1967 renamed to Mark of the GDR (M). Replaced in 1990 by the Deutsche Mark (DM) as a result of the monetary, economic and social union . |

||||

| founding | October 7, 1949 | ||||

| resolution | 3rd October 1990 | ||||

| National anthem | Rising from the Ruins | ||||

| Time zone |

UTC + 1 CET UTC + 2 CEST (March to September) |

||||

| License Plate | until the end of 1973: D, then: GDR | ||||

| ISO 3166 | DD, DDR, 278 no longer valid | ||||

| Internet TLD | .dd (provided, never assigned / delegated ) | ||||

| Telephone code | +37 (no longer valid; +37x reassigned to several states) | ||||

The German Democratic Republic ( GDR ) was a state that existed from 1949 until the establishment of German unity in 1990. The GDR emerged from the division of Germany after 1945, after the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) established a dictatorial regime at the instigation of the Soviet occupying power , which existed until the peaceful revolution in autumn 1989 . The official state ideology was Marxism-Leninism . In contemporary historical research , the system of rule in the GDR is sometimes referred to as real socialist , sometimes as communist . The rulers called the GDR a " socialist state of workers and peasants " and a German peace state, and claimed that the GDR had removed the roots of war and fascism . Anti-fascism became a state doctrine of the GDR.

Emerging from the Soviet Occupation Zone (SBZ), which arose with the division of defeated Germany , the GDR and its government, like the other real socialist Eastern Bloc countries , remained largely dependent on the Soviet Union for the four decades of its existence .

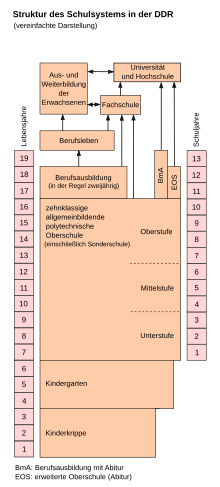

The prevailing political and economic conditions met with some rejection, but only rarely with active resistance from the population. However, this was unmistakable in the early phase of the popular uprising of June 17, 1953 , which was suppressed by Soviet troops. The emigration movement , which threatened the very existence of the state and which was drastically curbed by the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961 , also signaled clear rejection . The Ministry of State Security (short Stasi or colloquially "Stasi") was transformed to the whole society pervading organ of surveillance and targeted decomposition opposition activities and groupings. From kindergarten to university, state education and training was geared towards “ training to become a socialist personality ” in accordance with the ideology of Marxism-Leninism. Block parties and mass organizations in the GDR were subject to the SED leadership claim, not only in the People's Chamber elections , which were held via a single list , but also through an extensive system of control over the filling of management positions of all kinds within the framework of cadre policy .

The undemocratic political system and economic weaknesses led to an increasingly critical attitude of the population, especially since the first conference on security and cooperation in Europe (1973). With this conference, applications to leave the country were possible, against which the state was unable to respond despite various harassment in the further course. In the final phase, Erich Honecker's refusal to allow the reform process initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev in the Soviet Union to also take effect in the GDR intensified both the need to leave and the willingness to protest. Support for the system also waned within the power structures of the GDR, and the peaceful protests of many citizens that broke out in 1989 were no longer suppressed. These protests and a wave of emigration via Hungary and Czechoslovakia were essential components of the turning point and peaceful revolution in the GDR , which culminated in the unexpected fall of the Wall on November 9, 1989 and ultimately paved the way for the end of the GDR and German reunification .

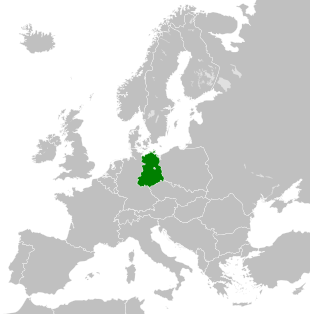

geography

The national territory of the German Democratic Republic consisted of today's German states Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania , Brandenburg , Saxony , Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia as well as the Neuhaus and Bleckede-Wendischthun office in Lower Saxony ; The inclusion of East Berlin was controversial . In terms of natural space, the GDR extended an average of 450 kilometers in a north-south direction, the mean east-west extension was around 250 kilometers. The northernmost point of the GDR was Gellort on the island of Rügen , northwest of Cape Arkona , and the southernmost point was Schönberg am Kapellenberg ( Vogtland ). The westernmost point was near the village of Reinhards in the Rhön , the easternmost near Zentendorf between Rothenburg and Görlitz .

In the north, the Baltic Sea formed a natural border, with the territorial waters of the GDR partially bordering those of the Federal Republic of Germany , Denmark and the People's Republic of Poland (viewed from the north-west to the north-east). The Oder-Neisse border with Poland existed in the east and the border with Czechoslovakia in the southeast . The inner-German border with the Federal Republic ran in the west and south-west of the GDR . In its center, the GDR enclosed the area of West Berlin .

The north and center of the GDR were part of the northern German lowlands, which were shaped by the Ice Age , and took up three fifths of the total area of the country. There, undulating ground or terminal moraine landscapes such as the northern and southern ridges alternate with flat sand areas and glacial valleys ( Mecklenburg Lake District , Märkische Seen ). Most of the lakes of the GDR can be found in this lowland , including the Müritz , Schweriner See and Plauer See , the largest inland waters. The south of the country, on the other hand, is occupied by the low mountain ranges ( Harz , Thuringian Forest , Rhön , Ore Mountains , Elbe Sandstone Mountains , Saxon Switzerland , Lusatian Bergland , Zittau Mountains ), into which pronounced basin landscapes protrude from the north ( Leipzig lowland bay , Thuringian basin ). The highest elevations in the GDR were the Fichtelberg with 1214.79 meters, followed by the Brocken (1141.2 m) and the Auersberg (1019 m).

Elbe and Oder , connected by different navigable canals ( Oder-Havel Canal , Oder-Spree Canal ), were the two largest river basins in GDR territory ; they were of great importance for inland navigation . The Elbe, with its numerous direct and indirect tributaries from the Saale , Havel , Mulde and Spree, drained most of the GDR's territory into the North Sea. The Oder, with the Lusatian Neisse as its largest tributary, was the second largest river basin; like Peene and Warnow, it drains into the Baltic Sea.

Rügen , Usedom , Poel and Hiddensee as well as the Fischland-Darß-Zingst peninsula belonged to the GDR as the largest islands in terms of area .

population

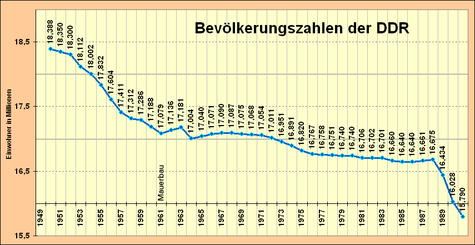

resident

In 1950, 18.388 million people lived in the GDR and East Berlin . At the end of the state in 1990 it was 16.028 million people. The decrease had several reasons:

- the permanent escape from the Soviet occupation zone and the GDR or the relocation from the Soviet Zone / GDR to West Germany ;

- in the early years of Weiterzug of displaced persons over the zone boundary in the West zones;

- the reduction in the birth rate, in particular through the introduction of the contraceptive pill and as a result of the legalization of abortions ("birth kink " , " pill kink "); in addition, as in other developed countries, there was also the trend away from larger families towards families with one or two children;

- the increase in the death rate due to adjustment to a normalized demographic development , after this had shown serious differences in the respective population groups in the early years of the Soviet occupation zone and GDR due to the war.

Due to international agreements, there were two small but still clearly demarcated foreign population groups, the Vietnamese contract workers and the 15,000 contract workers from Mozambique , also known as Madgermanes .

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

languages

The area in which the GDR was located belongs to the German-speaking area . In some districts of the Dresden and Cottbus districts , the West Slavic languages Upper Sorbian and Lower Sorbian , which are native to them, were also officially recognized (→ minority protection ).

The Benrath Line divides the country from west to east at the level of the districts of Magdeburg, Potsdam and Frankfurt (Oder) or on a line between Nordhausen and Frankfurt (Oder). To the north of it the East Low German dialects Mecklenburgisch-Vorpommersch and Mark-Brandenburgisch or Märkisch are spoken. They are parts of the Low German language (Low German). On the border with the state of Lower Saxony, East Westphalian and Brunswick-Lüneburg dialects such as Elbe-East Westphalian and Heideplatt are also widespread. One of the East Central German dialects is spoken south of the Benrath Line, where around 60 percent of the GDR population lived . This group includes the southern Mark dialect and the Thuringian-Upper Saxon dialect group . The area south of the Rennsteig in the Suhl district belongs to the East Franconian language area . In the south of the Vogtland ( district of Oelsnitz and district of Klingenthal ) the Upper German dialect North Bavarian is spoken, in addition the Upper German dialects Vogtland and further east the Erzgebirge are common. In the area around Görlitz, which until 1945 belonged to the province of Lower Silesia , the Silesian dialect has been preserved.

Religions and Religious Substitutes

State cult

In order to “ shape the younger generations” into “ socialist personalities ” and alienate them from the churches, the SED began a cultural war against the Christian churches in the 1950s and, from 1954, introduced the ritual of socialist youth consecration . In this quasi-religious substitute act, as a counter-event to confirmation and communion , combined with the pledge to serve the GDR, almost 99% of all 14-year-olds took part from the 1970s onwards. In addition, as a substitute for religion, analogous to the corresponding Christian rites, individual celebrations emerged, such as the socialist consecration of names (as a substitute for baptism), the socialist marriage and burial. In 1957 Ulbricht gave the youth consecration a state character and made it de facto a compulsory event with various means of pressure. While several attempts to introduce a socialist worker consecration failed, a pronounced state cult developed , with socialist festivals, forms of personality cult and a ritualization of the military. In 1958, the socialist state religion, created by Walter Ulbricht as a substitute for ethics, postulated the Ten Commandments of socialist morality and ethics . In 1988 the SED founded the Freethinkers' Association controlled by the Stasi as a replacement for pastoral care offered by the churches .

church

| Religion in the GDR, 1950 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Believe | percent | |||

| Protestantism | 85% | |||

| Catholic Church | 10% | |||

| Not connected | 5% | |||

| Religion in the GDR, 1989 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Believe | percent | |||

| Protestantism | 25% | |||

| Catholic Church | 5% | |||

| Not connected | 70% | |||

There were various religious communities in the GDR . The largest were the Christian churches. In addition to the eight Protestant regional churches and the Roman Catholic Church , which have been united in the Federation of Evangelical Churches in the GDR since 1969 , there were the following free churches : the Federation of Evangelical Free Churches in the GDR , the Federation of Free Evangelical Congregations , the Methodist Church , the Moravian Church , The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints ( Mormons ), the Seventh-day Adventist Fellowship , the Mennonite Congregation, and the Quakers . There were also the Evangelical Lutheran Free Church , the Evangelical Lutheran (Old Lutheran) Church and the Federation of Evangelical Reformed Congregations in the GDR.

In 1950 around 85 percent of GDR citizens belonged to a Protestant and around 10 percent to the Catholic Church. By 1989, the proportion of church members in the total population decreased significantly: 25 percent of the population were Protestants and 5 percent Catholics. The proportion of non-denominational in the total population rose from about 6 to about 70 percent in 1989. While most of the GDR were Protestant areas, there were also some traditionally Catholic areas: in Thuringia the Eichsfeld , the Rhön around Geisa , the traditionally bi-denominational city of Erfurt as well as the Upper Sorbian core settlement area in the Kamenz / Bautzen area .

“Full freedom of belief and conscience ” was written into Article 41, Paragraph 1 of the 1949 Constitution of the GDR . In the constitutional reality, however, SED officials and representatives tried to limit the undisturbed practice of religion, to reduce the influence of the churches and, above all, to withdraw church influence from young people. The prohibition of discrimination against Christians set out in Article 42 of the GDR constitution was undermined by many simple legal provisions that required an atheist profession. The anti-church policy of the GDR had its sharpest form in the early 1950s. It culminated in 1953 with the criminalization of the " young communities ". This led to relegations to schools and universities, including arrests, which were withdrawn in June 1953. Even afterwards, professing Christians had no more opportunities to study or to pursue a career in the state. Up until the end of the GDR, there were school-age children who were refused entry to the EOS due to a lack of youth consecration .

Other religions

There were some Jewish communities whose membership steadily decreased. But Jews in the GDR could live in safety without open anti-Semitism . On the other hand, the GDR rejected any compensation for Holocaust survivors because it saw itself as the successor state , but not as the legal successor to the German Reich . Like all Eastern Bloc states, the GDR took a stand against the " Zionist imperialism" of the State of Israel. In the 1980s, the SED paid more attention to the Jewish heritage and also invited Jewish organizations.

In addition, there were isolated Buddhist , Hindu and Muslim groups from the 1980s onwards . Dealing with paranormal ideas and practices in the GDR was examined from 2013 to 2016 in a knowledge-sociological DFG project. Such ideas were subject to strong reservations, especially in comparison with the Soviet Union. The anthroposophical movement was continued in the GDR, especially in the context of the Christian community . The esoteric St. John's Church had a special ecclesiastical role in the SED state .

Although the number of people with religious ties decreased considerably, the churches remained an independent social factor. From 1989/90 onwards, many people came together in the Protestant churches as semi-public assembly rooms, some of them without being religious themselves, who became the supporters of the peaceful revolution in the GDR.

story

The four decades between the founding of the GDR in October 1949 and the rapid fall in power of the SED since October 1989 form the main strand of GDR history. This was preceded by the division of Germany into zones of occupation decided and carried out by the victorious powers of World War II . From 1945 until the founding of the state in 1949 was the Soviet zone of occupation of the Soviet Military Administration in Germany (SMAD) was assumed that a land reform and the forced merger of the SPD and KPD to form the SED had already set the course. The opening of the border in November 1989 was followed by the initiation of the GDR's accession to the Federal Republic of Germany and the associated contractual arrangements between the two German states and in relation to the victorious powers.

Foundation of the GDR and development of socialism (1949–1961)

The German Democratic Republic was founded on October 7, 1949 ( Republic Day ) - a few months after the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany . On this day the constitution of the German Democratic Republic came into force, which had been in place since October 1948. The Second German People's Council was constituted as a provisional People's Chamber and commissioned Otto Grotewohl as Prime Minister to form a government . His colleague in the chairmanship of the SED, Wilhelm Pieck , was elected President of the GDR on October 11th .

The GDR was described as a real socialist people 's democracy . Political rule was exercised by the SED and extended to all areas of social life. In addition, there were “bourgeois” parties such as the LDPD and the CDU, but they had to submit to the SED. The CDU, DBD, LDPD and NDPD were part of the National Front (officially constituted on January 7, 1950) as block parties together with the SED and could not be elected separately. The Council of Ministers formally formed the government of the GDR, but was in fact subordinate to the Politburo of the Central Committee of the SED - the actual center of power. Walter Ulbricht was a member of the Politburo and, since 1950, Secretary General of the Central Committee of the SED . But even after the Soviet government had declared on March 25, 1954 that "the Soviet Union [...] wanted to establish the same relations [...] with the German Democratic Republic [...] as with other sovereign states", the sovereignty granted in this way remained restricted: the social historian Hans-Ulrich Wehler therefore describes the GDR as a " satrapy in the western frontier of the Soviet empire".

The first elections to the People's Chamber were set for October 15, 1950 and then held on the basis of a unified list. This date, more than a year after the constitution came into force, was opposed to the bourgeois politicians in the CDU and LDPD , as was the electoral mode. Meanwhile, their representatives received high posts in the new government: the LDPD chairman Hans Loch became finance minister , the CDU chairman Otto Nuschke became deputy head of government , his party friend Georg Dertinger foreign minister . Two of the most important foreign policy decisions of the GDR fell during his term of office: on July 6, 1950, the Görlitz Agreement with the People's Republic of Poland, in which the GDR recognized the Oder-Neisse line as the “state border between Germany and Poland”, and on September 29 In 1950 he joined the Council for Mutual Economic Aid (Comecon / Comecon).

Right from the start, true or supposed opponents of the SED regime were subjected to Stalinist repression. In the years 1950–1953, around 1,000 people were arrested by the State Security or its predecessor organization, extradited to the Soviet Union in violation of the GDR constitution and executed in Moscow.

Like the Federal Republic of Germany, the GDR claimed to speak for all of Germany. Initially, democratic constitutional features were also emphasized on the eastern side and the possibilities of an East-West German understanding were explored. However, they failed because of mutual insistence on certain incompatible basic conditions, as did Stalin's proposal for a united, neutral and democratic Germany in March 1952, since the Western powers again made free all-German elections a precondition.

As a result, in July 1952 , Josef Stalin gave Ulbricht's SED leadership a free hand to accelerate the development of socialism . In the economic field, there was now an increasing nationalization of industrial companies, in agriculture, collectivization based on the LPG model was elevated to a model. Propagandistically the innovations were accompanied by the long-term motto: “To learn from the Soviet Union means to learn to win.” This was accompanied by increased ideological repression directed against all adversaries and especially against the churches . At the low in May 1952 after a several kilometer exclusion zone sealed off inner-German border were in action vermin thousands aligned suspicious or dissident residents of the border areas forcibly relocated . The gradual adoption of the Stalinist Soviet model of society, without freedom of opinion , lack of worker participation and a materially privileged class of functionaries who occupied the important state and administrative positions, was accompanied by a personality cult promoted by the SED about the infallible leader Stalin, who, as the great " Teacher of the German labor movement and best friend of the German people ”.

The change of course ordered by the new Soviet leadership after Stalin's death in March 1953 , which included a suspension of the socialization and intensified ideological repression course, was followed by the SED, but without withdrawing the increased labor standards . The demonstrations directed against it in the eastern part of Berlin expanded into the nationwide uprising of June 17, 1953 . At least 55 people died in connection with the crackdown by the Soviet troops stationed in the GDR.

Financial aid from the Soviet Union, which also waived further reparations from the GDR and converted the remaining Soviet stock corporations in the GDR into state-owned companies, eased the supply situation and restabilized the SED regime under Ulbricht's leadership, which was now highly controversial. The de-Stalinization that Nikita Khrushchev on the XX. Had initiated the CPSU party congress , the SED leadership took part only hesitantly: In the GDR there was neither a personality cult nor mass repression, which is why there was not much that could be changed. But it contributed to a thaw in which students and intellectuals of the party hoped for further liberalization up to and including the reunification of Germany . The suppression of the Hungarian popular uprising in November 1956 by Soviet troops, which resulted in several thousand deaths and more than 2,000 death sentences, triggered a new wave of repression in the GDR. In 1959, the SED considered the time for a second attempt to “build socialism” to have come, by using all means more or less forceful means that in the first quarter of 1960 almost 40 percent of the agricultural area was taken over by “voluntary” accessions agricultural production cooperatives and that in the following year almost 90 percent of agricultural production was generated in socialist collectives . As a result, the number of refugees rose sharply again; 47,433 people left the GDR in the first two weeks of August 1961 alone. When Khrushchev condemned the terror of the Stalin regime in October 1961, Ulbricht distanced himself from the personality cult around Stalin and the crimes committed under his leadership, whereupon the GDR leadership initiated the de-Stalinization the USSR approved.

Between building the wall and policy of détente (1961–1971)

The massive emigration threatened the existence of the GDR, especially since an above-average number of young and well-educated people left the state. With the backing of the Soviet leadership, on the night of August 12th to 13th, 1961, People's Army Soldiers, People's Police and members of the working class combat groups of the GDR began to cordon off the border around West Berlin with barbed wire and armed forces. This resulted in the Berlin Wall , which became a symbol of the division of Germany and Europe. In addition, the inner-German border was secured more and more extensively by mine barriers , self- firing systems and border guards firing deliberately . Several hundred refugees were killed on the inner-German border in an attempt to overcome this blocking system , which the GDR propaganda referred to as the “ anti-fascist protective wall ”. These and other human rights violations committed in the GDR were documented by the Central Registration Office of the State Justice Administrations established in November 1961 in Salzgitter, West Germany.

Just two months after the border wall had begun, the SED leadership received new signals from Moscow in October 1961 amid a wave of repression against the regime opponents who were now prevented from fleeing, where CPSU General Secretary Khrushchev initiated a second wave of de-Stalinization . In East Berlin, people reacted by renaming streets, squares and facilities named after Stalin and rejecting the personality cult . However, this did not prevent Ulbricht from being celebrated on his 70th birthday in 1963 for his “simplicity, straightforwardness, simplicity, openness, honesty, cleanliness” and being propagated as a “statesman of the new type” distinguished by the “nobility of humanity”. In place of purely repressive measures against latently oppositional sections of the population, there was now more ideological persuasion and an economic policy oriented towards raising living standards . By working in the workplace, the people who had been deprived of the opportunity to escape sought to improve their standard of living and their chances of advancement as far as possible. "This attitude had a positive effect on economic development, the material improvements that it made possible in turn reduced oppositional moods, so that the relationships between the leadership and the population gradually became more objective."

The SED leadership gave up certain forms of harassment towards the young people, especially with regard to imports of Western dance forms. A Politburo resolution in 1963 stated: “It does not occur to anyone to tell young people that they should only express their feelings and moods while dancing to the waltz or tango rhythm. Which tact the youth chooses is up to them: the main thing is that they remain tactful! ”So the FDJ chairman, as a public activist for the fashion dance“ Twist ”, which had been frowned upon up to that point, worked hard to improve the“ musty ”image of the FDJ . At the third and last meeting of young people in Germany in May 1964, half a million young people from the GDR were represented as well as 25,000 participants from the Federal Republic and West Berlin. A youth program from Berliner Rundfunk went on air around the clock, was very well received and was given a permanent slot as DT64 .

However, this opening period in 1965 was quickly over soon after the overthrow of Khrushchev on October 14, 1964 and youth riots in Leipzig on October 31, 1965. It was a matter of curbing the "hooliganism" and taking action with the press against " bums ", "long-haired", "neglected" and "loitering". Now the FDJ leadership even supported campaigns in which students had their classmates cut off their hair. Honecker railed against the beat music on DT64 and against the "cynical verses" of the songwriter Wolf Biermann , against whom a performance ban was imposed.

The hopes of reform socialism associated with more freedoms that arose in the GDR population with the Prague Spring 1968, despite the renewed climate of repression, were suddenly dashed when parts of the United Armed Forces of the Warsaw Treaty under Soviet leadership adopted the Czechoslovak reform model of KPČ party leader Alexander Subdued Dubček by military means. The protests directed against it, mainly by young people in small groups in many cities in the GDR, were nipped in the bud by the security organs. In this context, the MfS ascertained over 2000 “hostile acts” up to November 1968.

The decisive importance of the course guidelines emanating from Moscow for the government of the GDR was again evident in the power struggle that broke out in 1970 for the party leadership between Ulbricht and Honecker. Honecker presented himself as the GDR politician who was more closely connected to the Soviet guidelines regarding the German-German rapprochement policy and found support in the SED Politburo for his criticism of Ulbricht's economic strategy, which was aimed at supporting future industries as well as research and industry, while Honecker There were complaints about backlogs and reduced production figures in the consumption-related area. It was not until Brezhnev's cooperation, after some hesitation and waiting and waiting, that Ulbricht resigned in April 1971.

From a new departure to stagnation (1971–1981)

After resigning from all offices except for that of the chairman of the State Council “for health reasons” and his being put aside by Honecker, Ulbricht died on August 1, 1973. Honecker had already given a change of course at the SED party congress in June 1971 and the “further increase in material and cultural standard of living of the people "of the party as" main task ". The working people in the “developed socialist society” should now participate more in the fruits of their labor. The “ unity of economic and social policy ” became the core slogan . One focus was placed on the construction of houses and the provision of adequate living space; by 1990 this social problem should be resolved. The increased employment of women in the work process was promoted through measures such as reducing working hours and extending maternity leave, as well as through the strong expansion of childcare facilities ( crèche , kindergarten ). The concentration on consumer goods production led to considerable results for GDR standards in equipping households with fridges and televisions, for example, and raised hopes for further increasing prosperity, even if the increase in minimum wages to over 400 marks and minimum pensions to over 230 marks until 1976 . However, the stimulation of the economy and consumption was only possible through increased indebtedness in western countries.

In December 1971, Honecker also set new accents in cultural policy , which were initially interpreted as liberalization and also used in this sense, while a restrictive reading prevailed after the mid-1970s at the latest:

“If one starts from the firm position of socialism, then in my opinion there can be no taboos in the field of art and literature. This applies to questions of content design as well as style - in short: the questions of what is called artistic mastery. "

A GDR-specific rehabilitation now also experienced the musical tastes of the younger age groups. At a dance music conference in April 1972 it was said: "We do not forego jazz, beat, folklore just because imperialist mass culture misuses them to manipulate aesthetic judgment in the interests of maximizing profit." In 1973, Honecker stopped the fight against reception of West German radio and TV stations in the GDR as well as the reservations against long hair, short skirts and blue jeans , the "riveted pants" that were previously known had been scourged as a symbol of Western decadence .

In foreign and German policy, Honecker followed the line of close ties to the Soviet Union, already championed by Honecker in the power struggle with Ulbricht, and invoked “firm anchoring in the socialist community of states”. Relations between the GDR and the Soviet Union were, according to the official reading in 1974, at a level of maturity "that there is practically no crucial area of daily life that does not reflect friendship with the Soviet Union."

In the course of the New Ostpolitik of Federal Chancellor Willy Brandt , beginning with the Erfurt summit in 1970, there were efforts to reach an understanding between the GDR and the Federal Republic of Germany. A transit agreement with foreign currencies for the GDR ensured easier transit through the GDR and improved the traffic route situation to and from West Berlin. With the basic agreement of September 21, 1972, which, among other things, regulated the mutual establishment of permanent representations in Bonn and East Berlin , the existence of both German states was mutually recognized on the basis of a peaceful coexistence. As a result, both German states became members of the UN in 1973 .

With the signing of the CSCE Final Act in 1975, the GDR government gained further renown in terms of foreign policy, but domestically it was faced with demands based on human rights based on the new international commitments. Citizens who petitioned the Secretary General of the United Nations and the governments of the CSCE signatory states who accused the GDR officials of depriving them of their liberty after rejecting an application to leave the country were arrested in October 1976 and convicted of " subversive agitation ", one year later in the Federal Republic deported . The West German government turned to the prisoner ransom in 1964 to 1989, 33,753 political prisoners from East German prisons total of 3.4 billion German marks to - the historian Stefan Wolle sees parallels with the soldiers trade under Landgrave Friedrich II of Hesse-Kassel. While of absolutism . In the Politburo, Honecker vigorously tried to prevent the emergence of an emigration movement motivated in this way. The first SED secretaries of the district leaderships were instructed on how to proceed as follows:

“Lately, revanchist circles in the FRG have been trying desperately to organize a so-called civil rights movement in the German Democratic Republic [...] It is necessary to reject these circles accordingly. This also requires that our competent organs reject all applications that apply for release from our citizenship and exit to the FRG on the basis of the Helsinki Final Act or other justifications . "

Honecker issued instructions that all such applicants were to be dismissed from their employment relationships and ensured that they were criminalized as part of an amendment to the criminal law in April 1977.

Also in the fall of 1976, with the expatriation of the songwriter Wolf Biermann, the beginning of the cultural and political opening with which the Honecker era had begun ended. Biermann's concert in Cologne, at which he was as drastic and critical of the GDR functionaries as he was communist and loyal to the GDR itself, provided the last pretext for Biermann's long-planned removal from the GDR. Unexpected for the SED superiors, however, came the protests against this expatriation measure , initiated by well-known GDR writers and generating a broad response, even beyond their own artistic circles . Of the twelve first signatories of the protest note of November 17, 1976, only two took part in the eighth writers' congress in May 1978. The others were not granted admission or voluntarily waived.

In terms of foreign policy, the situation for the GDR government became more complicated in the second half of the 1970s with the emergence of Eurocommunism, which was breaking away from the Soviet model, in Western Europe , with the establishment of the Charter 77 human rights group in Czechoslovakia, and at the transition to the 1980s the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and through the protest strikes in Poland in the summer of 1980, which were popularized with the independent trade union Solidarność .

Decline and turnaround (1981–1990)

The second oil crisis in 1979/80 had dramatic consequences for the GDR's economy , which led to accelerated economic decline. The Soviet leadership, themselves in economic difficulties, cut the GDR's annual crude oil deliveries on preferential terms from 19 to 17 million tons. Honecker intervened several times and asked Brezhnev “whether it is worth two million tons of oil to destabilize the GDR and to shake our people's trust in the party and state leadership”. The GDR had meanwhile specialized in processing parts of its Soviet crude oil contingent using the oil refineries in Schwedt, Böhlen, Lützkendorf and Leuna ( Leuna works ) and selling them on the Western European market at a good profit and against Western currencies. Since Honecker's protests did not get caught, but were answered with the request to support the difficulties of the USSR in solidarity, since otherwise its position in the world would be endangered with “consequences for the whole socialist community”, the financial and economic system of the GDR got into a “tangle of Worries and hopelessness ”(according to the chairman of the State Planning Commission Gerhard Schürer ).

In 1982 the GDR was threatened with insolvency . It was largely saved from this by two West German billion-dollar loans in 1983 and 1984, initiated by the head of the Commercial Coordination Department responsible for foreign exchange procurement and at the same time Stasi officer on special operations (OibE) Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski , who won the Bavarian Prime Minister Franz Josef Strauss as an advocate could by including a defusing of the GDR border regime was promised. The Schmidt III cabinet (1980–1982) had previously considered lending the GDR three to five billion DM through a “straw bank” in Zurich . The supply of the population with high-quality consumer goods could not be solved satisfactorily. Color televisions, refrigerators with freezers and fully automatic washing machines of almost western standards not only had to be paid for in a comparatively expensive manner, but also had to be paid for with long waiting times: “The delivery time for a fully automatic washing machine was up to three years; With at least a decade of waiting , the Trabant remained the uncrowned leader. "

On the Soviet side, however, the special German-German agreements also sparked distrust of the GDR leadership. This is one of the reasons why Honecker's visit to the Federal Republic , which was recorded as the culmination of the international recognition of the GDR, only came about in 1987. As had Mikhail Gorbachev to the Soviet Union glasnost and perestroika already embarked on a course of reform and had friendly parties and governments in the Eastern Bloc countries now free hand for the internal development . This shifted the basic foreign policy coordinates for the SED superiors, who were used to seeing the Soviet leadership as the guarantor of the GDR and their own power. They strictly refused to follow Gorbachev's model, now even imposed censorship on the Soviet media and propagated “ socialism in the colors of the GDR ”. While a number of Eastern Bloc countries relaxed their exit policy after Gorbachev took office, the GDR adhered to its restrictions, with which it isolated itself from the socialist camp at the CSCE follow-up conference in 1988 when it came to the recognition of human rights .

With this, the SED superiors in the GDR population met with incomprehension and increasing resistance, even in their own SED ranks. Organized forms of protest were mainly to be found in a peace movement that had arisen since the early 1980s. It consisted of local small groups , some of which were also committed to ecological and Third World issues and some of them developed under ecclesiastical protection and encouragement. The dissatisfaction with the SED regime took on increasingly clear forms in the course of 1989, especially during the protest against the falsified results of the local elections in May, and culminated in a diverse motivated civil rights movement. The GDR government also had serious problems with the mass exodus of GDR citizens via Hungary , which had dismantled its border security with Austria in the spring of 1989, made it possible for them to flee at the Pan-European picnic and, from September 11, 1989, also for GDR citizens to officially leave the country allowed to Austria. The protests of the reform-oriented civil rights movement were expressed in the Monday demonstrations that took place regularly during the autumn . While the demonstrators were pushed aside and harassed by the security forces at the celebrations in East Berlin for the 40th anniversary of the GDR's founding on October 7, the mass demonstration in Leipzig only two days later led to the groundbreaking breakthrough for the peaceful revolution in the GDR : Even the resignation of Honecker on October 18 and his replacement by Egon Krenz as well as the offer of the new SED leadership for a dialogue with the population did not stop the fall of power of the state party. The announcement of imminent travel opportunities for GDR citizens to the western part of Germany led to the rush to the Berlin Wall and its opening on the night of November 9, 1989. In 1989, around 344,000 people left the GDR for the Federal Republic.

The new government under Hans Modrow , the former 1st Secretary of the District Management of the SED Dresden , was controlled by the opposition forces at the round table , who also pushed for the dissolution of the Stasi apparatus , while the slogan changed during the continued Monday demonstrations: We are the people ! ”Until then, challenged the state power, the slogan“ We are one people ! ”Was now aimed at German unity.

With the victory of the Alliance for Germany in the Volkskammer election on March 18, 1990 , the course was set in this direction ( see main article German reunification ). A grand coalition under the first freely elected GDR Prime Minister Lothar de Maizière , energetically supported by the Kohl / Genscher government, pursued the goal of the GDR's accession to the Federal Republic according to Article 23 of the Basic Law after the entry into force of a monetary, economic and social union On July 1, 1990, the ratification of the Unification Treaty and - as a foreign policy requirement - the conclusion of the two-plus-four treaty with the former victorious powers of World War II, the GDR was absorbed into the Federal Republic of Germany on October 3, 1990.

politics

Constitution

The striking changes that were made to the original constitution of the GDR reflect the development and the respective political guidelines of the SED leadership, which held the actual power in the state. Because both the state structure and the organization of the parties and mass organizations were subject to the principle of “ democratic centralism ”.

Article 1, paragraph 1 of the 1949 Constitution of the GDR read: “Germany is an indivisible republic; it is built on the German states . ”Since 1968, instead, with emphasis on the socialist character and the SED leadership role, it was said:

“The German Democratic Republic is a socialist state of the German nation. It is the political organization of the working people in town and country who, under the leadership of the working class and their Marxist-Leninist party, are realizing socialism. "

With the renewed change in 1974 (after the Basic Treaty and the admission of both German states to the United Nations ), the connection to the German nation was omitted:

“The German Democratic Republic is a socialist state of workers and peasants. It is the political organization of the working people in town and country under the leadership of the working class and its Marxist-Leninist party. "

The Council of Ministers as the government of the GDR was constitutionally the highest executive organ of the state and was elected by the People's Chamber. The ministers came from the various parties of the National Front, but in practice had less influence than the secretaries and heads of departments who were represented in the central committee of the SED and who belonged to the respective ministry.

The actual center of power was the Politburo , which was chaired by the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the SED . The decisions made at this highest level became binding for the lower levels in the manner of democratic centralism. Cadre policy and “ nomenklatura ” contributed to this, as did the increasingly extensive surveillance apparatus of the Ministry for State Security . Printed matter , radio and television, literature and art were subject to censorship , those with political differences were subjected to repression and were not infrequently criminalized.

The State Council of the GDR was - after the death of the first and only President Wilhelm Pieck in September 1960 - as a collective presidential body the head of state of the GDR. Walter Ulbricht became the first chairman of the State Council . Until the fall of the Berlin Wall, the chairman of the State Council was always provided by the SED.

Elections and legitimation of the regime

In all elections that took place in the GDR before 1990, those eligible to vote were only presented with a single list of candidates from the parties and mass organizations that were linked together in the National Front . There was no possibility of voting for individual persons or parties. For the elections, which were based on a purely confirmatory function of the rulers, the electorate was elaborately mobilized and, in the collectives to which they belonged, motivated or forced to participate with some emphasis. The individual voting process itself was usually carried out without any effort and not in secret: most of the voters - under careful observation - refrained from using the voting booths set up in the back of the polling station , but simply folded their slip of paper with the unit list and threw it in unread the urn . This process was popularly called "going to fold". As early as the first Volkskammer election in 1950 , extensive electoral fraud resulted in the picture that had become common on this scale from Soviet votes: 98 percent voter turnout and 99.7 percent approval.

These types of unity elections do not allow any conclusions to be drawn as to how large a percentage of the population approved or disapproved of the SED regime. Historians rely on estimates to answer this question. Stefan Wolle points out the consistently high voter turnout of 99%, which the SED repeatedly referred to for legitimation purposes. Since nobody had to fear prosecution for refusing to vote and the state propaganda was not taken seriously by anyone, Wolle assumes that the citizens of the GDR "partly reluctantly, partly approvingly and to a large extent indifferent" gave their vote to the candidates of the National Front . To explain it, he cites "an apparently deeply rooted striving for harmony with those in power, a joy in submission and the collective humiliation of outsiders".

The historian Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk emphasizes that no regime can be based on repression alone. The fact that the real existing socialism in the GDR actually met with approval was due to three promises of the regime: that war should never again start from German soil, that fascism or National Socialism should never repeat itself, and the promise of social justice. The GDR therefore acted as an anti-fascist peace state in which “everyone was allowed to live and work according to their possibilities”. Indeed, some wealth began to spread in the 1960s. The unity of economic and social policy enforced by Honecker in 1971 served the same purpose. In the words of Hans-Ulrich Wehler:

"At the price of obedience, loyalty to the system, the renunciation of active influence and readiness for conflict, an authoritarian-paternalistic care in the style of the propagated anachronistic 'security' was introduced."

According to the historian Arnd Bauerkämper , the party’s official promise of social equality met with a wide response. The real social inequality in the GDR and in particular the privileges of the nomenklatura, such as the forest settlement of Wandlitz , which is described as luxurious, led to a legitimacy gap and thus significantly to the fall of the regime in 1989.

The American historian Andrew I. Port, on the other hand, believes that the GDR had no legitimacy in the sense of Max Weber's sociology of domination . The fact that it did not collapse sooner despite the widespread dissatisfaction with its numerous shortcomings, he attributes to a widespread "unwilling loyalty". Many behaved defensively, participated as far as it was unavoidable and promised advantages. The numerous conflicting interests between the social groups and individuals in the GDR prevented the emergence of a broad opposition movement until 1989.

State symbols

|

|

The flag of the German Democratic Republic consisted of three horizontal stripes in the traditional German democratic colors black, red and gold with the state coat of arms of the GDR in the middle, consisting of a hammer and compass , surrounded by a wreath as a symbol of the alliance of workers , peasants and intelligence . The first drafts of Fritz Behrendt's coat of arms only contained a hammer and a wreath of ears, as an expression of the workers 'and peasants' state . The final version was mainly based on the work of Heinz Behling .

With the law of September 26, 1955, the national coat of arms was designated with a hammer, compass and wreath of ears, while the national flag was still black, red and gold . By law of October 1, 1959, the coat of arms was added to the state flag. The public display of this flag was viewed in the Federal Republic of Germany and West Berlin as a violation of the constitution and public order until the end of the 1960s and was prevented by police measures (cf. the declaration by the federal and state interior ministers , October 1959). It was not until 1969 that the federal government decreed "that the police should no longer intervene anywhere against the use of the flag and coat of arms of the GDR."

At the request of the DSU , the first freely elected People's Chamber of the GDR decided on May 31, 1990 that the GDR national coat of arms should be removed in and on public buildings within a week. Nevertheless, until the official end of the republic , it was still used in a variety of ways, for example on documents.

The text risen from the ruins of the national anthem of the GDR comes from Johannes R. Becher , the melody from Hanns Eisler . From the beginning of the 1970s until the end of 1989 the text of the hymn was no longer sung due to the passage “Germany united fatherland”.

Legal system

Like the power-political structures in general, the legal system of the GDR was shaped by the SED's claim to leadership, as laid down in the constitution. There was no separation of powers based on the independence of the courts ; there was also a lack of other constitutional standards. In politically motivated proceedings, for example, lawyers were subject to arbitrary restrictions in safeguarding the interests of their clients: access to files was only granted in part, and discussions with clients were sometimes not allowed at all or only in a monitored manner.

The Criminal Code and the Code of Criminal Procedure of the GDR were decisive for the jurisprudence . In the area of criminal law, the GDR judiciary politically criminalized in part on the basis of vague and indefinite facts such as "subversive agitation", "public degradation", "impairment of state and social activity", "hooliganism", "anti-social behavior" or "unlawful connection" undesirable behavior. So blurred worded offenses did not meet the constitutional principle of certainty . In addition, there was an extensive and hardly foreseeable interpretation of such facts. Particularly in the first years of the GDR, extremely harsh penalties were often imposed for objectively harmless acts for " boycott agitation ". In politically significant proceedings, courts and the public prosecutor's office in the GDR were sometimes actually forced to act contrary to the legal situation due to specific requirements on the part of the SED.

The first constitution from 1949 still contained democratic and constitutional principles such as the separation of powers, certain basic rights such as the right to freedom of expression or assembly , the rule of law, freedom of the press and the independence of the courts and the administration of justice . Individual elements were also retained in the later constitutions of the GDR, but were actually not granted or only granted to a very limited extent. The low binding effect of the constitution and the lack of independence of the judiciary were shown, among other things. in secret procedures such as the Waldheim trials . In addition to its influence on the courts, the SED used internal party procedures (including Paul Merker ) to sanction members. The Central Party Control Commission was responsible for this.

Since there was no effective administrative jurisdiction , fundamental rights were not enforceable - there was no legal protection against the actions of the state organs (as the state authorities were called). Instead, since 1975 citizens who did not agree with their measures or decisions had the legally guaranteed possibility of submitting submissions to administrations, for example the city council , party branches, the People's Chamber or the Council of State. The petitioners did not have a legal right to have their request fulfilled. Such submissions could also be sent to companies and other institutions. Entries regarded as justified may have been complied with, albeit arbitrarily and in a way that is often incomprehensible to the public. Submissions that were unwelcome to the authorities, especially with regard to exit applications, could lead to repression against the applicants. An estimated half a million to a million such submissions were received by the state and the party every year. Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk sees an authoritarian tradition in the input system of the GDR , the historian Martin Sabrow compares it with the enlightened absolutism of Frederick II .

The planning law was a result of the party-controlled planned economy , the resolution of conflicts between different regional authorities and authorities , such as in infrastructure projects, environmental protection and monument law not provided for or unregulated.

International commitments entered into by the GDR, e.g. For example, the respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms recognized within the framework of the CSCE gave opposition groups and dissidents more room for maneuver in terms of formal law. The same applied to the freedom of religious belief, which was incorporated into the GDR constitution in 1968 .

The regulations of the civil code were initially adopted in the GDR. The age of majority had already been reduced to 18 in 1950 (in the Federal Republic this did not take place until 1975), and the mandatory official guardianship for illegitimate children was abolished in favor of full parental authority of the mother. In 1966 family law was transferred to a separate law, the Family Code, and the distinction between illegitimate and legitimate children was abolished. The (remaining) civil code was replaced in 1976 by the civil code of the German Democratic Republic . Property , patent and inheritance law were strictly limited, contract law was committed to the planned economy. As in all real socialist states, an interdisciplinary and interdisciplinary labor law developed in the GDR in the sense of a right to work . This corresponded to the self- image of the SED, anchored in the traditions of the labor movement , according to which the marketing of labor on a free labor market was rejected as exploitation .

Parties and mass organizations

The party pluralism that also existed in the GDR alongside the dominant SED from 1949 to 1989 - the so-called socialist multi-party system - arose from the early efforts of the SMAD to bring the implementation of the Potsdam Agreement with regard to denazification and democratization in line with the goals of its own occupation policy. Therefore, in order to preserve the democratic appearance, no one-party system as in the USSR should initially be set up. Even bourgeois and nationally oriented parts of East German society should be included in an anti-fascist alliance, which was then formed into the National Front . The founding of parties that promised to open up Christian, liberal and national milieus was also emphatically promoted, and the spectrum of parties was combined to form the democratic bloc . As block parties were represented:

- Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU)

- Democratic Peasant Party of Germany (DBD)

- Liberal Democratic Party of Germany (LDPD)

- National Democratic Party of Germany (NDPD)

The purpose of recording and integrating as many parts of society as possible into everyday political life in accordance with the SED was also served by the mass organizations, in which those who were less politically interested could be encouraged to cooperate collectively. These included:

- Democratic Women's Federation of Germany (DFD)

- Free German Youth (FDJ)

- Free German Trade Union Confederation (FDGB)

- Kulturbund (KB)

- Pioneer organization Ernst Thälmann as a political mass organization for children

- Association of Mutual Farmers Aid (VdgB)

The distribution of mandates and offices among the parties and organizations was independent of the elections and remained constant for a long time. It is true that the SED itself held only a good quarter of the mandates, according to the proportional representation that was fixed before every election to the People's Chamber; but with the deputies of the mass organizations, mostly also SED members, it could not fail to have a majority, even if the bloc parties had wanted to behave less obediently than was usual under the pressure of the circumstances. In the 9th electoral period (1986–1990) the People's Chamber consisted of the following 500 members:

- SED: 127

- DBD: 52

- CDU: 52

- LDPD: 52

- NDPD: 52

- FDGB: 61

- DFD: 32

- FDJ: 37

- Kulturbund: 21

- VdgB: 14

Of these, 271 MPs were designated as workers, 31 farmers, 69 salaried employees, 126 members of the intelligentsia and three as other MPs. In the history of the People's Chamber, up until the turning point in 1989, there were only one dissenting votes, namely in 1972 from the CDU on the liberalization of the regulations on abortion through the law on the interruption of pregnancy . In addition to the People's Chamber, there were people's representatives at the district assembly level, district level and communal level, also elected according to a list of candidates drawn up beforehand.

In the turning point of 1989 , numerous new parties and organizations such as the New Forum , Democratic Awakening and the Social Democratic Party in the GDR emerged . On December 1, the People's Chamber deleted the SED leadership claim from the constitution. The SED itself tried to free itself from its dictatorial legacy by expelling its former leadership and gradually renaming it to the Party of Democratic Socialism . On March 18, 1990, these parties ran for the first and only free elections to the People's Chamber .

Restricted public life

The Marxist-Leninist doctrine as read by the SED gave the guidelines and limits to public life in the GDR. This also applied to the interpretation of the fundamental rights, for which it was stated in the constitution of 1968 that the GDR guaranteed all citizens “the exercise of their rights and their participation in the management of social development. It guarantees socialist justice and the rule of law. ”(Article 19, Paragraph 1). Furthermore, the following principle follows the statement: "Work with us, plan with us, govern!" the agreement with the GDR socialism bound:

- The free development of personality was subordinate to the goal of developing socialist personalities and was only promoted in this sense.

- The right to demonstrate on official occasions partly had the character of a collective obligation, but was not suffered in the case of oppositional statements and constituted a criminal offense in the form of " boycotts " or "subversive agitation" .

- The freedom of expression in the form of the published opinion and ensuring freedom of the press were in the GDR reality tied to line loyalty within the current bandwidth. Statements deviating from this were subject to the various levels of state censorship . The “abuse of the media for bourgeois ideology”, which disciplined authors and journalists and, in addition to newspapers, books and other printed matter, also affected radio and television, satire, art and science, was also punishable .

Public life was strictly controlled, but its intensity fluctuated. At the beginning of the 1950s it was still quite possible to publicly e.g. B. to thematize the inadequate supply of spare parts for motor vehicles and to specifically name the guidelines of the government and its organs as the culprits. In later years the publication of such articles was unthinkable. In the cultural field, the accompanying censorship was subject to fluctuations. A period of relaxation came in the early 1970s when films like The Legend of Paul and Paula were made. However, the phase was rigorously ended with the ban on the system-critical rock band Renft in 1975 and Biermann's expatriation in 1976. A second phase of easing set in in the mid-1980s when films like Whispering & Screaming and Coming Out, as well as rock albums like Riot in the Eyes of Pankow and February by Silly , were released. That period of relaxation ended up in the peaceful revolution of 1989 , during which the public protests were not put down.

There was a shortage in the range of magazines approved by the censorship, especially in the weekly and hobby magazines. Illustrated magazines such as the magazine “ Neues Leben ” or the television magazine “ FF bei ” were very difficult to obtain. Popular media, such as “ Das Magazin ”, the only magazine that had nudes in its program, was limited in circulation in the GDR. Performances of the few political cabarets in the GDR (including Die Distel and Leipziger Pfeffermühle ) were sold out for years, but the performances on the radio or TV were only broadcast in exceptional cases and in parts. In the case of books, especially fiction , the printing approval procedure de facto led to prior censorship and work-specific control.

The "complete and perfect" surveillance of the public space in the GDR, which is unique according to wool - "The state security lay over the country like a giant octopus and penetrated the most hidden corners of society with its suction cups" - created a climate of constant uncertainty and a substitute public, fed by political jokes and rumors. The suppression of an independent public resulted in the general absence of political scandals . Scandalous public disputes, for example about theater performances in the 1950s and 1960s, the self-immolation of Pastor Brüsewitz in 1976, Biermann's expatriation or the coffee crisis in the GDR from 1977 onwards remained exceptions. They were also closely related to the reports in western media that were accessible to GDR citizens and the use of which the government was unable to object. With the exception of the so-called valley of the unsuspecting , West German radio and television programs could be received everywhere in the GDR . Especially after the building of the wall, political programs like “ Kennzeichen D ” or “ Kontraste ” with correspondent reports from the GDR contributed to the information about changes in the GDR. Since these also reached large parts of the GDR population, the GDR leadership tried to counteract propagandistically, in particular in the program " The Black Canal " moderated by Karl-Eduard von Schnitzler . The every evening "collective departure" by means of western television, which was tolerated in the Honecker era, undermined the credibility and effectiveness of state propaganda on the one hand, but also broadened the information horizon to the west for those physically prevented from traveling to the west, thereby easing the situation to a certain extent.

An all-encompassing political control of society was therefore not feasible on the part of the GDR leadership. For example, certain informal networks and freedom remained for the churches . The planned economy, with its unplanned side effects and deficits, also promoted the perception of self-interest and informal self-help activities in the collective. In spite of all general loyalty to the line, there was a certain amount of freedom, for example, in the bloc parties, where the bourgeois "you" were upheld and had no chance of getting into the real key positions of the state, but due to the lack of mass in relation to SED membership, they even expected better chances was able to move forward on the “party line” and to move up on a proportional basis in a privileged position compared to the GDR ordinary citizen.

The GDR had one of the highest suicide rates in the world. The SED leadership largely hushed up and made taboo on the subject of high suicidal tendencies .

Political opposition and its fight by the Stasi

The term GDR opposition refers to many different currents and forms of protest that have existed side by side and one after the other during the four decades of GDR history. They often appeared individually or in locally organized small groups. In the early phase of the GDR, the SED reformers who advocated a “special German path to socialism” formed a counterweight to the Ulbricht course, which was stripped of its ground through purges and targeted criminal prosecution. Opposition groups have emerged since the 1970s, adhering to a socialism modeled on the Prague Spring , committed to human rights, peace and all-round disarmament, or starting initiatives against environmental pollution and destruction. These resistors found support in parts of the Protestant Church, for example through the provision of rooms and publication opportunities.

Until the turning autumn of 1989 , including when the New Forum was founded , the civil rights activists in the GDR mainly advocated reforms and had to accept professional disadvantages, surveillance and, in some cases, repression. Politically dissenters were particularly observed in the nationwide state surveillance system, in particular with the help of the “unofficial employees” of the MfS (popularly: “Horch und Guck”). Depending on the degree of resistance to be expected from the point of view of the security organs , Stasi victims were fought with a whole range of methods, from mere intimidation to harassment and decomposition to long-term imprisonment in the Bautzen prison . In the case of “defectors” from the ranks of the Stasi and escape helpers , there were also kidnappings and murders on the secret orders of the Stasi. Torture and solitary confinement were among the various means of coercion, especially in the MfS pretrial detention centers , to make political prisoners compliant and confess. Physical torture was more likely to be used until at least the 1960s. Later, more and more psychological torture methods were used to wear down political prisoners and break their will, as the use of psychological torture is more difficult to prove.

Women and Family Policy

The law on mother and child protection and women's rights , passed in 1950, formed the legal basis of women's and family policy in the GDR . The compatibility of work and family was taken for granted for women in the GDR and was specifically promoted. By 1989, almost 92 percent of women were integrated into working life, which shows a significantly higher employment rate for women compared to the Federal Republic of Germany: on the one hand, the employment of women corresponded to the socialist conception of gender emancipation and, on the other hand, it served to cover the labor needs of the GDR, which was disproportionately high many male skilled workers had turned their backs at an early stage by fleeing. In management positions, however, women were clearly underrepresented.

The promotion of female employment was created, for example, through the development of a comprehensive infant and child care system or through special curricula and study plans for student families. As part of family policy , the state promoted married couples primarily when they had children. This was done through special loans and through a clear preference in the allocation of housing. On the issue of abortion, under the Abortion Act introduced in 1972, women were given the choice of terminating the pregnancy within the first twelve weeks. Nevertheless, the number of live births rose by a third between 1973 and the peak in 1980.

In everyday life, the emancipation of women through employment was usually accompanied by a double burden on the one hand at work and on the other hand in the household and family, in that traditionally male tasks were simply added to traditionally female roles. A survey from 1970 showed that of the average 47 hours of housework per week, 37 hours were done by women, around 6 hours by men and around 4 hours by “others”.

Environmental policy

The reindustrialization of the post-war period was associated with increasing environmental pollution in both parts of Germany. It culminated in the 1970s, when environmental protection was first weighted in economic policy - but not in the GDR: a lack of investment leeway made a rapid approach to environmental protection impossible in view of the already inadequate production of goods. The party leadership always considered the approach to western consumer conditions more important than measures to protect the environment. In addition, there was the ignorance of the GDR leadership towards committed citizens who would like to do something to protect the environment. In the 1980s, however, more and more environmental activists, cycling clubs etc. were formed. In a new study from 2009, the ecological balance of the GDR is described as "catastrophic". In the absence of hard coal deposits, lignite- fired power plants burned raw lignite on a large scale . The consequences were, among other things, the highest emissions of sulfur dioxide and the highest dust pollution of all European countries. The air pollution caused increased mortality; More than twice as many men died from bronchitis , emphysema and asthma as the European average. Around 1.2 million people did not have access to drinking water that met the general quality standard. Only 1 percent of all lakes and 3 percent of all rivers were considered intact in 1989. Until then, only 58 percent of the population was connected to a sewage treatment plant . 52 percent of all forest areas were considered damaged (see also forest dieback ). More than 40 percent of the garbage was improperly disposed of.

There were no high-temperature incinerators for hazardous waste . On the grounds that the environmental data were used by the class enemy to discredit, the data was classified as " Confidential classified information " from 1970 and as "Secret classified information " from the beginning of the 1980s and thus withheld from the public. Criticism of environmental policy was ruthlessly suppressed; also criticism of the extensive uranium mining that was carried out by the bismuth in Saxony and Thuringia. For a long time, the GDR was the fourth largest uranium producer in the world after the Soviet Union , the United States of America and Canada .

Rubbish imports from western countries (especially from western Germany ) brought the GDR foreign currency income that it urgently needed. The dumping prices in the GDR were sometimes less than a tenth of the prices charged in properly managed landfills in West Germany; For the garbage suppliers (companies, municipalities, federal states), garbage transport was therefore worthwhile despite the sometimes high transport costs. Part of the foreign exchange generated in these transactions, in which the Commercial Coordination Department and the Ministry for State Security played a leading role, ended up in the "Honecker account" and the "Mielke account" of Deutsche Handelsbank AG and was able to supply the SED- Elite are used in Wandlitz . Towards the end of the 1980s, the MfS determined not only in the Federal Republic but also in the population of the GDR a growing environmental awareness and, in some cases, a negative attitude towards garbage imports into the GDR. In contrast, those responsible for the disposal of West German rubbish in the GDR accepted non-compliance with German environmental standards.

In the GDR, public passenger transport and freight transport by rail were heavily promoted, which at the time was not ostensibly for environmental reasons, but nevertheless represented a sustainable transport concept that was initially discarded during the fall of 1989. In view of climate change , bad air and a lack of space in large cities, there is now a rethinking, and parts of this transport policy are being taken up again.

The automobile production of the GDR was neglected economically, so that further developments in terms of environmental protection were hardly implemented. The Trabant and Wartburg cars produced by the GDR contributed significantly to environmental pollution with their outdated two-stroke engines and their harmful exhaust gases. Exhaust gases from a two-stroke engine are clearly smell and visible due to their high KH content (blue exhaust plumes). Compared to a four-stroke engine without a catalytic converter, on the other hand, a two-stroke engine only emits a tenth of the amount of acid rain and smog that causes nitrogen oxide (NO x ).

Administrative structure and capital city problems

Since its foundation, the administrative structure of the GDR was characterized by a strong central power. The first constitution of 1949 constituted a federal structure with the states of Mecklenburg , Brandenburg , Saxony-Anhalt , Thuringia and Saxony . These five countries were originally its own constitutional body , the Bundesrat , on the legislation involved the GDR, in addition East Berlin had an advisory capacity. Nevertheless, the GDR was not a real federal state , but, as constitutional lawyer Karl Brinkmann writes, “a unified state , moreover as a uniting power , more centralized. There was no federalism at all, but a strict unitarianism ”.

With the administrative reform of 1952 , the states were relieved of their functions. 14 districts took their place as the new middle level of state administration. At the same time, the number of urban and rural districts was greatly increased as part of a district reform . In 1958, the federal states were finally formally abolished.

According to the constitution , Berlin was the capital of the GDR , which was a violation of the agreement reached by the Allies at the Yalta Conference in 1945 . Although after this entire Berlin as a four- sector city under joint Allied control, none of the zones of occupation and thus could not belong to one of the two resulting German states, the successive occupation of the eastern part by the GDR was ultimately tolerated by the western powers de facto (→ Berlin question ) . In 1977 the special features of East Berlin compared to the GDR were dismantled: the East Berlin administration was called the “ Magistrate of Greater Berlin ” until then . On January 1, 1977, the Ordinance Gazette for Greater Berlin and with it the official documentation of the adoption of laws from the GDR by the East Magistrate was discontinued. the control booths on the border of the eastern sector from Berlin to the GDR were removed. The three western allies always emphasized the special constitutional status of the whole of Berlin, which results from the occupation sovereignty exercised by all four victorious powers . Finally, the Western powers reminded the Soviet Union to “keep their obligations with regard to Berlin”, although since 1955 a gradual concealment of the legal situation in the Eastern sector could be observed, even if there was no legally binding document by which it was fully identified as part of the GDR.

The State Council of the GDR put East Berlin on a par with the districts in 1961. The following districts existed until the end of the GDR (bb according to community number key bbkkgg; bb: district (numeric); kk: district (numeric); gg: municipality (numeric)):

|

|

Foreign and Development Policy

The GDR leadership was not allowed to pursue an independent foreign policy under Soviet influence. Even in the 1952 Stalin Notes , the GDR represented a power-political and diplomatic asset for the Soviet leadership: “If a reunification of the four zones of occupation had proven to be feasible, which corresponded better to the foreign policy interests of the Soviet Union than the status quo , the GDR regime would have been was not sacrosanct. "Only when the all-German option failed at the beginning of 1954 due to western preconditions that demanded free all-German elections, and when the acceptance of the Federal Republic into the western military alliance NATO was immediately apparent, did the USSR admit to the GDR in March of the same year," to determine at its own discretion about internal and external affairs ”. In May 1955, the GDR was already among the founding members of the Warsaw Pact .