Deportation (law)

The compulsory measure of deportation (in Switzerland also: deportation and repatriation ; in EU law also: repatriation ) is the enforcement of the obligation to leave the country of a person who does not have the nationality of the country from which they are to be deported. It is carried out as a real act by state authorities, usually in the person's country of origin or in a third country .

Conceptually inseparable from the deportation is the rejection (as the required z. At a boundary because the conditions of entry visa ) are missing, as are the forcible return after a successful entry, because it was forbidden: it is performed usually within six months .

Germany

Legal position

Legally, deportation and repatriation mean the same thing. German law on aliens uses the term deportation, European law mainly uses the term repatriation. The word deportation has a negative connotation; the word repatriation , on the other hand, is sometimes viewed as euphemism or as a euphemism.

In colloquial language and in the media, the terms expulsion and deportation are often used synonymously. However, these have different meanings.

- The expulsion is an administrative act under the law on foreign nationals under the Residence Act (AufenthG), which ends the legality of a stay, invalidates any existing residence permit ( Section 51 (1) No. 5 AufenthG) and thus leads to an obligation to leave the country. In addition, an expulsion also has a blocking effect. A foreigner who has been deported may no longer be granted a residence permit even if he / she has a claim (exception: humanitarian right of residence in accordance with Section 25 (5) of the Residence Act); there is an absolute re-entry ban, which also applies to short-term stays, e.g. B. in the transit zone of an airport or short visits to relatives. A foreigner whose stay endangers public safety and order, the free democratic basic order or other significant interests of the Federal Republic of Germany, will be expelled if the interests in the departure must be weighed up, taking into account all the circumstances of the individual case (see the interest in deportation in accordance with Section 54 AufenthG) with the interests of the foreigner remaining in the federal territory (see the interest in remaining in § 55 AufenthG) shows that the public interest in leaving the country prevails ( § 53 Abs. 1 AufenthG). Special protection regulations according to EU law and association law (especially for EEA citizens and Turkish nationals ) must be observed . In the event of expulsion, the blocking effect of the stay and re-entry ban comes into effect when the deportation order is announced; it remains in place even if the person concerned voluntarily complies with the expulsion.

- The deportation , on the other hand, is a coercive means within the framework of administrative coercion, with which the illegal stay of the foreigner is ended. Deportation can be made if the obligation to leave the country is enforceable ( Section 58 AufenthG) and voluntary departure does not take place. What the enforceability of the obligation to leave the country is based on (deportation order from the immigration authorities, mere expiry of the period of validity of the residence permit, unauthorized entry without a residence permit ) is fundamentally irrelevant. An expulsion order is therefore not necessarily followed by deportation (namely not if the expelled person leaves voluntarily), nor does deportation require prior deportation; deportation is possible after the expiry of the period of validity of the residence permit if the person concerned does not leave voluntarily and has not applied for an extension. In contrast to expulsion, the blocking effect of the absolute re-entry and residence ban does not apply to non-expelled persons until they are deported; the mere threat of deportation or deportation order does not yet trigger it. Anyone who has lost their right of residence without being expelled can avert a re-entry ban by voluntarily leaving the country; if there is a compulsory deportation, this has the same negative consequences as an eviction order.

If the deadline for voluntary departure has expired and there are no obstacles to deportation (see Section 60a, Paragraph 2, Sentences 1 and 2 of the Residence Act), the authorities can continue to tolerate the foreigner's whereabouts at their discretion, "if there are urgent humanitarian or personal reasons or significant public ones Interests require his temporary further presence in the federal territory "( § 60a Abs. 2 S. 3 AufenthG), or has to deport the foreigner. To ensure the removal can detention be arranged whose conditions in § 62 are fixed Residence. A distinction must be made between large and small preventive detention. Large preventive detention requires a court order, must be proportionate, can last up to six months and can be extended by a maximum of twelve months if the foreigner has prevented his deportation. The prerequisite for detention is the existence of certain reasons for detention that indicate a risk of flight. These are 1.) the unauthorized entry, 2.) the existence of a special danger for the security of the Federal Republic of Germany emanating from the foreigner, 3.) the change of the place of residence without notification of the new address to the competent authority, 4.) the culpable failure to act a deportation date, 5.) thwarting the deportation in any other way and 6.) the well-founded suspicion that the foreigner will evade deportation. In contrast to large preventive detention, small preventive detention does not require any special reasons for detention, because its purpose is to be able to carry out imminent deportations, usually collective deportations. It can be ordered for a maximum of two weeks if it is certain that the deportation can be carried out.

For a planned arrest for the purpose of detention pending deportation, the authority needs a judicial decision in advance. In the event of an accidental arrest (spontaneous arrest), a judicial order must be obtained immediately afterwards by the authority. At the latest during detention, the necessary prerequisites for carrying out the deportation must be created (procurement of the necessary travel documents and, if necessary, the consent of the country of origin to take them back, booking a flight), whereby the authorities must work particularly quickly to maintain the proportionality of the deprivation of liberty ( acceleration requirement ) .

With the deportation and / or deportation, a residence and re-entry ban arises, which is to be limited in the deportation order at the latest, however, immediately before deportation ( Section 11 subs. 2 AufenthG). The authorities often require that the cost of a deportation be paid before re-entry. In certain cases (illegal employment, illegal entry) the employer or the airline can also be obliged to bear the costs of the deportation.

Change of German deportation and deportation law

The law of August 19, 2007 ( Federal Law Gazette I, p. 1970 ) in Section 5, Paragraph 4, Section 54, No. 5 and 5 a of the Residence Act (previously as of January 1, 2002, Section 8, Paragraph 1, No. 5 of the Aliens Act ) The additional reasons for the refusal of residence permit and the reasons for deportation are based on the anti-terror measures jokingly named "Otto Catalog" after the former Federal Minister of the Interior Otto Schily . According to this, the well-founded suspicion of membership or support of a group that supports terrorism at home or abroad is sufficient to refuse a residence permit or to be expelled.

Great expectations were placed on this amendment to make it easier to deport violent Islamists in the future. These have not been fulfilled. Because the accusation of support for terrorism must be proven beyond doubt in order to stand up in court. However, this is often not possible because those affected either act conspiratorially or move in an environment that is difficult for the authorities to understand (e.g. hate preacher in a mosque where Turkish or Arabic is spoken).

In terms of procedural law, a new deportation order should enable violent terrorist offenders to be removed more quickly. According to § 58a AufenthG, which came into force on January 1, 2005 , the respective highest state authority (Ministry of the Interior, Senator of the Interior) can also act against a foreigner on the basis of a factual forecast to avert a particular danger to the security of the Federal Republic of Germany or a terrorist threat issue a deportation order without prior expulsion. The deportation order is immediately enforceable; there is no need for a deportation threat. The Federal Ministry of the Interior can initiate the procedure if there is a particular interest on the part of the federal government ( Section 58a, Subsection 2, Residence Act). An application for the granting of provisional legal protection according to the administrative court regulations must be submitted to the Federal Administrative Court within seven days of the notification of the deportation order ( Section 50 (1) No. 3 VwGO ). The deportation may not be carried out until the deadline has expired and, if the application is submitted in good time, until the court has decided on the application for provisional legal protection ( Section 58a subs . 4 AufenthG). Deportation may also not be carried out if the conditions for a ban on deportation in accordance with Section 60 (1) to (8) of the Residence Act are met ( Section 58a (3) of the Residence Act).

This regulation has also remained meaningless for a long time. The case law of the Federal Administrative Court on Section 58a of the Residence Act, in which the court had to deal with the material requirements, was not issued for over 10 years. It was not until 2017 that the Federal Administrative Court decided on the first deportation orders in accordance with Section 58a of the Residence Act.

In July 2017, the law for better enforcement of the obligation to leave the country was passed ( Federal Law Gazette I p. 2780 ), which aims to facilitate the deportation of rejected asylum seekers and tighten the rules for so-called endangered persons. The design looks u. a. provide that endangered persons can more easily be taken into deportation detention.

Deportation proceedings

Several authorities are responsible for deportation. The foreigners authorities of the federal states are generally responsible for issuing the threat of deportation and for carrying out the deportation ( Section 71 subs. 1 of the Residence Act). There is an exception in the case of an asylum procedure. In the event of an application being rejected, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) issues the threat of deportation ( Section 34 AsylG). However, the foreigners authorities of the federal states are again responsible for executing the deportation ( Section 40 AsylG). The deportation has to be threatened in writing beforehand ( Section 59 AufenthG). The person concerned is to be given a deadline for voluntary departure. As a rule, the threat of deportation is issued together with the administrative act with which the right of residence expires.

In the countries in which there are exit facilities , the immigration authorities can order the person to take up residence in an exit facility if the person concerned refuses to provide information about himself or to participate in obtaining return travel documents ( Section 61 (2) of the Residence Act).

If resistance by the person to be deported is to be expected during the intended deportation, the immigration authorities can avail themselves of the support of the police in the context of enforcement assistance . The actual repatriation of the foreigner to his home country is the responsibility of the authorities responsible for police control of cross-border traffic ( Section 71, Subsection 3, No. 1 of the Residence Act), i.e. usually the Federal Police . The police in the federal states are also responsible for preparing and securing deportation, insofar as arrest and application for detention in the context of an intended deportation are concerned ( Section 71, Subsection 5, Residence Act).

If the person to be deported is ill or undergoing treatment or has a medical certificate, he will be examined by a doctor. It is determined whether the transport can lead to damage to health and whether the ability to travel can be established, for example, by an accompanying person. In their role in the medical examination before deportation, however, doctors see themselves in some cases in a medical-ethical conflict.

Scheduled aircraft are usually used for deportation. The foreigners are taken over by law enforcement officers from the immigration authorities or the state police and brought into the aircraft. If non-cooperative or violent behavior is expected, or if a deportation has already failed, the foreigner can be accompanied by law enforcement officers from the Federal Police. This is also to prevent foreigners from causing pilots to refuse transport through their behavior . It is preferable to separate offenders from non-offenders and especially from families with children on the plane. In exceptional cases, aircraft are only chartered with persons to be deported.

Under special conditions, the executing authority can dispense with a deportation in individual cases and on a discretionary basis (so-called discretionary tolerance ). This must be distinguished from a so-called deportation freeze, which is usually based on a decision by a state ministry and temporarily prohibits the executing immigration authorities from deporting certain groups of foreigners.

Deportation peculiarities for stateless persons and persons of unknown nationality

The Residence Act (and thus the residence permit requirement) applies to all persons who are not Germans i. S. d. Article 116, Paragraph 1 of the Basic Law ( Section 2, Paragraph 1 of the Residence Act), thus also for stateless persons and persons whose nationality has not been clarified. What applies to every foreigner also applies to stateless persons: under international law there is only one obligation to take back one's own citizens. In the case of stateless persons or persons whose nationality has not been clarified, deportation is generally not possible due to the lack of a state willing to accept them. How many asylum seekers (cannot) submit a passport is not officially recorded. The private association “ Pro Asyl ” is of the opinion that this is “the vast majority”. According to Wilfred Burghardt, the chairman of the federal-state repatriation working group, more than 80 percent of the asylum seekers who have entered the country state that they have no passports or other documents. "Many have lost ID, birth certificates and other identifying documents, destroyed them before entering Germany or they are not presented to the German authorities."

Before the start of the deportation, the nationality must either be clarified via the national passport or the destination country must have given consent to accept the person. The European Union has concluded readmission agreements with many states in which these states undertake to take back their own citizens. The readmission assurance is preceded by an examination of the target country as to its readmission obligation; Here, too, the nationality of the person being deported is clarified before the deportation.

Under international law, it is not permissible to dispense with the readmission obligation by expatriating the person concerned abroad . The expatriation may be effective under the domestic law of the state concerned; According to international law, however, the foreign state in which the expatriate is located is still obliged to take the former national back into his home.

Apart from that - if citizenship persists - international law obliges them to accept their own citizens and to allow transfers. Some states violate this (e.g. Iran, which in principle does not issue a national passport if the person concerned declares that he does not want to leave Germany). Some states are not cooperative in determining citizenship and make the issuing of a national passport dependent on conditions that are almost impossible to meet. This includes states that have their own interest in their nationals staying because they support their relatives living in their home country with transfers in foreign currency (US dollars, euros), which ultimately also benefits the country of destination.

If deportation is not possible due to unclear citizenship or lack of a national passport, there is an actual obstacle to deportation. The person concerned then first receives a tolerance ( § 60a Abs. 2 AufenthG), his deportation is suspended. The existing obligation to leave the country remains unaffected (Section 60a, Paragraph 3 of the Residence Act); the stay remains illegal. Illegal periods of residence will not be offset against residence rights that depend on a minimum length of stay (e.g. settlement permit or naturalization ). Tolerated persons are also often excluded from benefit claims (e.g. according to SGB II ). If the continued stay is not at fault (e.g. because the person concerned has done everything possible on his part to remove the obstacle to deportation - this includes applying for a national passport at the diplomatic mission in question), he can after 18 months Receiving a residence permit for humanitarian reasons ( Section 25 (5) of the Residence Act). Only then will his stay become legal and deportation will no longer be considered for the duration of this residence permit.

Deportation of foreigners who have already applied for protection in another member state of the European Union

There are special features for asylum seekers who have already applied for admission in another EU member state. As a rule, these people are refused the asylum procedure in Germany. They are then deported to the state in which they were first admitted ( Section 27 and Section 34a AsylG). This safe third country must carry out the asylum procedure and receive them. The procedure is based on the Dublin Convention (DC).

However, regardless of its non-existent obligation under international law, every member state of the DÜ has the option of carrying out the asylum procedure on a voluntary basis. Article 3 (2) of Regulation (EC) No. 343/2003 provides a right of self-entry . Because of the uncertain reception situation for refugees in Greece , the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees is initially making use of this option until January 12, 2012 for all refugees who would have to be transferred to Greece. As a result, a legal dispute before the Federal Constitutional Court has been settled.

Number of persons obliged to leave Germany and deportations from Germany

According to the Center for Return Assistance ( ZUR ), the number of people required to leave the country was 246,737 on June 30, 2019 ; a year earlier, 234,603 people were required to leave the country.

According to the ZUR , the largest groups of foreigners required to leave the country come from Afghanistan (20,921), Iraq (18,457) and Serbia (12,659).

While a total of 11,496 people were deported in the first half of 2019, the figure was 12,266 in the same period of the previous year.

Number of deportations to Germany

The Ministry of the Interior registers hundreds of deportations of Germans from abroad every year (2014: 306; 2013: 336; 2012: 363), only counting those cases in which the federal police were involved. A total of 220 Germans were deported from the United States in 2010, a high since records began there in 2001. In Germany, the returnees may be entitled to take part in integration courses and to receive public support.

According to estimates from the immigration authorities from the beginning of 2019, more than a third of the people deported from Germany subsequently returned to Germany. The Interior Ministry commented that there was no statistical data on this and that no reliable information could be given.

criticism

Opponents of the deportation point to the consequences for those affected and, above all, to the fact that decisions by authorities are prone to errors under the real situation of imperfect information. The legal situation in Germany prohibits deportation if the person concerned is threatened with the death penalty or if there is a significant concrete danger to life, health or freedom ( Section 60 subs. 3 and subs. 7 sentence 1 of the Residence Act). But also a deported person can be in a z. B. life-threatening situations arise, for example if the defense attorney defends his client poorly in administrative and / or court proceedings or if those involved in the deportation procedure underestimate the dangerous situation of the (later) deported person.

In some cases, an obligation to leave the country is immediately enforceable, even if there is still an appeal against the relevant decision in the main proceedings . The possibility of making additional urgent applications to postpone a deportation cannot always be used.

Deportations from the Federal Republic of Germany have often been accompanied by critical public attention, for example the threatened deportation of the vocational student Asef N. on May 31, 2017, during which there were clashes between police officers and 300 opponents of deportation. Attention was also drawn to the deportation of 69 Afghans on July 4, 2018 , which was the highest number of deportees in an airplane to date and in which one of the persons was illegally deported. A few days after deportation, one of the deportees died of suicide.

The case of Sami A. , a Tunisian classified as a threat , who was deported on July 13, 2018 , also attracted attention . The administrative court of Gelsenkirchen had issued a ban on deportation the previous evening, but only communicated this on the morning of July 13th. After the deportation, it ordered his repatriation in an urgent decision, against which the city of Bochum lodged a complaint with the Higher Administrative Court of Münster . The North Rhine-Westphalian refugee minister Joachim Stamp said that he only learned of a ban on deportation shortly before 9 a.m. on the day of the deportation and that at that point in time he saw no opportunity to intervene. The federal police told the media that the deportation could have been prevented even after the plane had landed at 9:08 am until it was handed over to the Tunisian authorities at 9:14 am.

Several deaths due to the violent execution of the departure are documented: In 1994 the gagged Kola Bankole suffocated while being deported on board a Lufthansa plane, in 1999 the Sudanese Aamir Ageeb from the consequences of being handcuffed by officers of the Federal Border Police. The psychological consequences of the deportation procedure, which opponents associate with around 20 documented suicides by deportation detainees since the 1950s, are also discussed .

The frequent failure of deportations is regularly discussed. For example, according to media reports from February 2019, citing information from the Federal Police, more than half of all planned deportations in 2018 failed. Of the 57,035 planned returns, 30,921 did not take place. In 2018, more than 27,000 foreigners intended for deportation were not handed over to the federal police by the federal states as planned. According to Federal Interior Minister Horst Seehofer (CSU), the reasons for the canceled handovers were that the people concerned were "not traceable" or "did not have the necessary travel documents".

Switzerland

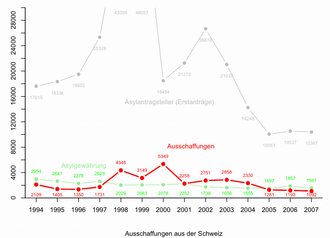

The Swiss term is deportation. Deportation can be ordered if a person without a residence permit allows a deadline that was set to leave the country to pass, or if there is a legally binding eviction or removal decision for persons in custody. The cantonal authorities are responsible.

On July 10, 2007, the Swiss People's Party (SVP) launched a " Federal People's Initiative" For the deportation of criminal foreigners (deportation initiative) ", which aims to simplify the deportation of foreigners. The initiative was declared to have taken place in March 2008. In June 2009, the Federal Council recommended it for rejection due to concerns about its compatibility with international law, in particular the principle of non-refoulement , and recommended that an indirect counter-proposal be drawn up. It came to a vote together with the direct counter-draft on November 28, 2010 and was adopted with a majority of 52.9 percent. The counter-proposal was rejected with 54.2 percent.

The federal popular initiative "To enforce the deportation of criminal foreigners (enforcement initiative )" was a popular initiative of the Swiss People's Party (SVP) that was voted on on February 28, 2016. The initiative intended to literally and literally implement the deportation initiative adopted in the referendum on November 28, 2010, and to expand the offenses that lead to deportation. In the opinion of the SVP, the implementation proposal passed by the Swiss Parliament does not meet the original requirements of the adopted initiative, in particular because the envisaged hardship clause allows a court to waive the deportation of a criminal foreigner in individual cases.

The Federal Council and Parliament recommended that the sovereign reject the initiative, which was what happened in the vote on February 28, 2016.

France

The French term is expulsion. In 2013 around 27,000 people were deported. 20,800 of them were éloignements d'étrangers en situation irrégulière (the rest were régularisations ).

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia deported 243,000 people to Pakistan between 2012 and 2015. 40,000 Pakistanis were deported from October 2016 to February 2017. The deportees were former migrants who had previously come to the kingdom to work. According to official information, they were deported for visa violation and security concerns. Observers assumed, however, that the mass deportations took place in order to prevent unrest caused by lack of wages.

European Union

Return of third-country nationals

In EU law, instead of “deportation”, “repatriation” is usually used, which legally means the same thing. In December 2008, the European Union issued common standards on the procedure in the Member States for returning illegally staying third - country nationals . According to this, detention can be imposed for up to six months, in exceptional cases up to 18 months. The re-entry ban was limited to five years and minimum standards for the deportation procedure were defined. For the details cf. the main article → Return Policy .

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) has confirmed in a ruling that the Return Directive does not forbid the member states from classifying an illegal entry after a deportation as a criminal offense. The fundamental rights and the principles of the Geneva Refugee Convention must, however, be preserved.

The Dublin Regulations and their implementing regulations provide for several options for transferring an asylum seeker to the Member State responsible for the asylum procedure. On the one hand, it can take the form of a repatriation (either as a controlled departure in which the foreigner is accompanied to the German train station or airport, or as an escorted transfer, in which the foreigner is taken by police officers in the plane, car or train to the relevant EU Land is brought). On the other hand, there is the possibility of a self-organized transfer in which the foreigner leaves voluntarily and then reports to the authorities of the responsible Member State. It is up to the Member State which form of transfer to choose. If the asylum seeker takes the initiative, however, the immigration authorities responsible for the execution of Dublin transfers must, for reasons of proportionality, examine whether, as an exception, the person concerned can be given a transfer organized and financed by himself instead of being returned, provided that it appears certain that he is voluntary goes to the other Member State and reports to the competent authority there in due time. This is conceivable, for example, if he himself wishes to have family reunification in the other Member State.

In March 2019, the ECJ ruled that an asylum seeker can be transferred to another Member State under Dublin III even if there is a lack of social benefits, unless he is put into extreme material hardship that goes against the prohibition of inhuman or degrading conditions Treatment (Article 4 EU Charter of Fundamental Rights or Article 3 ECHR) would be violated. However, exceptional circumstances in cases of particularly vulnerable people must be taken into account separately.

Repatriation of EU citizens

Council of Europe

On May 4, 2005, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe drafted 20 guidelines on deportation, including guideline 1 on voluntary return, guideline 2 on the disposal of deportation, guideline 3 on the prohibition of collective expulsions, guideline 4 on the notification of the deportation order, guideline 5 on Appeal against the order on deportation, guidelines 6 to 11 on detention pending deportation, guidelines 12 and 13 on cooperation and obligations of states, guideline 14 on statelessness and guidelines 15 to 20 on forced deportation.

United States

Extent of deportation

The USA deported the largest number of illegal immigrants to date with 410,000 people in the 2012 budget year . In 2016, 240,255 people were deported. Although US President Donald Trump had announced more deportations, according to estimates from September 2017, slightly fewer deportations will take place in the 2017 financial year than in 2016. Although the ICE had arrested many people who had previously lived in the country as illegal immigrants, many are using it Arrested all available legal means in order to avoid deportation. In 2017, around 600,000 corresponding proceedings were pending before the courts, which threatened to overload the judicial system.

According to ICE , tens of thousands of those deported each year are the parents of a child with US citizenship.

literature

- Gerda Heck: ›Illegal Immigration‹. A contested construction in Germany and the USA. Edition DISS Volume 17. Münster 2008, ISBN 978-3-89771-746-6 ( Interview heiseonline November 10, 2008)

- Steffi Holz: Everyday uncertainty. Experiences of women in custody. Unrast, Münster 2007, ISBN 978-3-89771-468-7 (contains an appendix on legal issues)

- Julia Kühn: deportation order and detention. An investigation into § 58a and § 62 of the Residence Act in terms of constitutional law. Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-428-13091-7 .

See also

Web links

- general

- Caravan for the rights of refugees and migrants

- Asylum information network - case law and counseling addresses

- Database for researching the country of origin

- Germany

- BMI fact sheet for enforcing the obligation to leave the country (deportation) , July 2016

- Current information from anti-deportation opponents and a critical press review on the subject of deportation in Berlin

- How does the federal government work with countries of origin to carry out deportations? , Federal government

- Information portal on German residence law

- Addresses of the refugee councils in the German federal states

- Deportation policy using Hamburg as an example (PDF file; 96 kB)

- Problem case deportation (1/2) - How Nigeria and Germany work together In: Online presence of the TV station 3sat , February 11, 2015.

- Infographics on the subject of deportations in Germany from the Federal Agency for Civic Education / bpb

- Austria

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Helena Baers: “Deportation” or “Return”? Legally the same - but still a difference. In: Deutschlandfunk. April 5, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2017 .

- ↑ a b c Selected questions on asylum standards in EU member states (file number: WD 3 - 3000 - 084/15). Scientific Services of the German Bundestag - Department WD 3: Constitution and Administration, June 3, 2015, pp. 5-6 , accessed on April 20, 2016 .

- ↑ cf. Julia Kühn: deportation order and detention. An investigation into § 58a and § 62 of the Residence Act in terms of constitutional law. Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-428-13091-7

- ↑ Resolutions of March 21, 2017 - 1 VR 1.17 - and - 1 VR 2.17 - , of May 31, 2017 - 1 VR 4.17 - and of July 13, 2017 - 1 VR 3.17 - .

- ↑ Better enforce the obligation to leave the country. German Federal Government, May 18, 2017, accessed on May 20, 2017 .

- ↑ draft law of the federal government. Draft law to improve the enforcement of the obligation to leave the country. In: Printed matter 18/11546. German Federal Government, March 16, 2017, accessed on May 20, 2017 .

- ↑ Traumatized refugees: Mental health problems usually go undetected. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt 2009, Volume 106, No. 49: A-2463 / B-2115 / C-2055. Deutscher Ärzteverlag, 2009, accessed on July 26, 2016 .

- ^ Klaus Martin Höfer: Rejected asylum seekers. Return with dignity. Deutschlandfunk, January 6, 2017, accessed on January 21, 2018 .

- ↑ Die Welt, Why Germany Deports So Few Asylum Seekers , March 22, 2015

- ↑ BVerfG, decision of January 25, 2011 , Az. 2 BvR 2015/09, full text.

- ↑ Press release No. 6/2011 of the BVerfG of January 26, 2011.

- ^ A b c Roman Lehberger: Confidential analysis: the number of deportations is falling . In: Spiegel Online . September 27, 2019 ( spiegel.de [accessed October 24, 2019]).

- ↑ a b Stephanie von Selchow: Foreigners, go home! Deported to Germany. In: MiGAZIN. January 10, 2017, accessed December 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Stefan Kaufmann: Simply deported - to Germany. In: Handelsblatt. April 16, 2015, accessed December 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Marcel Leubecher: "Every third deportee travels back to Germany" Welt.de of February 17, 2019

- ↑ SPIEGEL online: Who is the young Afghan Asef N. Accessed on July 19, 2018 .

- ↑ ZEIT online: 69 Afghans deported on a joint flight. Retrieved July 19, 2018 .

- ↑ Gabor Halasz, Sebastian Pittelkow, Hannes Stepputat: Afghane illegally deported. Retrieved July 19, 2018 .

- ^ Sueddeutsche Zeitung: Seehofer on suicide of deported refugee: "Deeply regrettable". Retrieved July 19, 2018 .

- ^ Sascha Lübbe: When politics and the rule of law collide. In: time online. July 17, 2018, accessed July 22, 2018 .

- ↑ City of Bochum files a complaint against the decision of the VG Gelsenkirchen: NRW wants to prevent Sami A. from returning. In: Legal Tribune Online. July 18, 2018, accessed July 22, 2018 .

- ↑ Federal police contradict NRW refugee minister Joachim Stamp. In: time online. July 22, 2018. Retrieved July 22, 2018 .

- ↑ Report from www.no-racism.net of January 3, 2008 Suicide in the deportation prison in Berlin-Köpenick

- ↑ Figures from the Federal Police: More than half of all deportations in 2018 failed. In: Spiegel Online . February 24, 2019, accessed February 24, 2019 .

- ↑ Barcelona: Hundreds of thousands protest for separatist leaders. In: maz-online.de . February 24, 2019, accessed February 24, 2019 .

- ↑ SR 142.20 Federal Act on Foreign Nationals , Art. 69

- ^ Federal People's Initiative 'for the deportation of criminal foreigners (deportation initiative) , Swiss Federal Chancellery. Regardless of the title deportation initiative , the text of the initiative concerns the loss of the right of residence or the expulsion of foreigners who have committed criminal offenses; the actual deportation (deportation) of expelled persons is not mentioned.

- ↑ Popular initiative of February 15, 2008 'For the deportation of criminal foreigners (deportation initiative)

- ↑ http://www.interieur.gouv.fr : Politique d'immigration 2013–2014: bilan et perspectives

- ↑ Immigration: 27,000 expulsions in 2013

- ↑ Bethan McKernan: "Saudi Arabia 'deports 40,000 Pakistani workers over terror fears'" The Independent dated February 13, 2016

- ↑ European Court of Justice (ECJ), AZ: C-290/14. Quoted in: ECJ - re-entry after deportation can be a criminal offense. Reuters, October 1, 2015, accessed October 1, 2015 .

- ↑ Preamble, (24): “Transfers to the Member State responsible for examining an application for international protection can be made on a voluntary basis in accordance with Regulation (EC) No. 1560/2003 of the Commission [..], in the form of controlled departure or in Accompanying take place. ", Dublin III Ordinance of June 26, 2013.

- ↑ a b BVerwG 1 C 26.14. In: Press Release No. 72/2015. September 15, 2015, accessed October 22, 2017 .

- ↑ Marcel Keienborg: ECJ on secondary migration: Even with deportations, human dignity remains inviolable. In: Legal Tribune Online. Retrieved April 22, 2019 .

- ^ Twenty Guidelines for Forced Expulsion

- ↑ Nick Miroff: "Deportations fall under Trump despite increase in arrests by ICE" Washington Post, September 28, 2017

- ↑ ICE data: Tens of thousands of deported parents have US citizen kids. Center for Public Integrity , accessed December 1, 2018 .