Uprising of June 17, 1953

The uprising of June 17, 1953 (also popular uprising or workers' uprising ) is the uprising in which there was a wave of strikes, demonstrations and protests in the days around June 17, 1953 in the GDR , with political and economic demands were connected. He was violently suppressed by the Soviet Army ; 34 demonstrators and bystanders as well as five members of the security forces were killed.

This first anti- Stalinist uprising had numerous causes, including the accelerated development of socialism in the GDR, the associated ignorance of the GDR leadership towards the needs of the working class, including its decision to raise labor standards , and other mistakes by the SED .

The uprising of June 17th acted as a political signal for the people of the Eastern Bloc countries .

From 1954 until German reunification in 1990 , June 17 was the national holiday of the Federal Republic of Germany as the “ Day of German Unity ” ; it is still Remembrance Day .

background

From July 9 to 12, 1952, the 2nd party conference of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) took place in the Werner-Seelenbinder-Halle in East Berlin . Under Walter Ulbricht's formulation of the “systematic construction of socialism ”, society was “ Sovietized ” and state power was strengthened based on the Soviet model. The five federal states were newly divided into 14 districts , with East Berlin being included as the 15th administrative unit. The Barracked People's Police (KVP), which was being set up, was to become a “national armed forces”, a “people's army”. The remaining middle class in the GDR was harassed more, in particular farmers and small commercial and industrial enterprises were to be forced to give up their independence through increased taxes. They were also blamed for the economic problems.

In the spring of 1953, the state budget was very tense: expenditure of 1.1 billion marks was not covered by income. The development of the KVP had allowed the GDR's military spending to grow to 3.3 billion marks (8.4% of the budget) in 1952. A large part of the state budget was tied up by the expenditures for armament, occupation costs and reparations payments (including the costs for the SAGs ). Armament and post-war costs for the GDR amounted to 22% in 1952 and over 18% of the total state budget in 1953.

The SED's economic policy had directed investments mainly into heavy industry, which had previously had no basis in the GDR. As a result, urgently needed funds for the food and consumer goods industries were missing, and supplies for the population were impaired. At dusk there were power cuts to meet the needs of the industry at peak times. The weak economic development of the nationalized economy - after all, two thirds of industrial production was generated by state-owned companies - had led to an enormous excess of purchasing power in the GDR in the early 1950s. Wrong developments in the planned economy should be corrected through higher taxes and duties, wage and premium cuts and later through a "new course".

In connection with the economic policy described, there was also the almost complete elimination of private holiday organization and private holiday letting in favor of the FDGB holiday service (February 1953: " Aktion Rose ").

In spring 1953 the existence of the young GDR was indeed threatened by a serious food crisis. Expropriations and land reform had already led to the abandonment of farms in the mid-1940s. The parcelling after the land reform and, above all, the lack of agricultural equipment by many new farmers made economic work hardly possible. The collectivization policy of the SED at the beginning of the 1950s should lead to more efficient management and increasing yields. The real goal of collectivization, however, was the dissolution of the independent peasant class and, in particular, the smashing of the more profitable large farms. The tax increases for farmers and the withdrawal of food cards caused further displeasure. In the autumn of 1952, harvests were also very below average. The result was a lack of food. Basic foodstuffs were still allocated with food cards until 1958 and the prices of the state trade organization (HO) were well above the level in the Federal Republic of Germany, for example a bar of chocolate cost 50 pfennigs in the west and eight marks in the east . The GDR citizens had only half the amount of meat and fat available from the pre-war period. Even vegetables and fruit were not sufficiently produced. There were long lines in front of the shops. The prosperity gap to West Germany widened due to the shortcomings of the central administration economy . Since the GDR was not allowed to accept the assistance of the Marshall Plan and had to pay higher reparations, it found itself in an economically worse starting position. Even the support of the Soviet Union to stabilize the GDR was not enough to compensate for the consequences of reparations and a planned economy.

The dramatic increase in the emigration movement (" voting with one's feet "), which had been constant since the founding of the GDR, in the first half of 1953 represented an economic as well as a social problem. Another factor that put pressure on the political situation was the high one Number of prisoners in the GDR.

The repression against the illegal organization Junge Gemeinde, which is designated as the central youth organization of the Evangelical Church and fought against, played a major role . Numerous student pastors and youth guards were in custody (Johannes Hamel, Fritz Hoffman, Gerhard Potrafke). Church recreational homes were closed and taken over by the Free German Youth (FDJ) ( Mansfeld Castle , Huberhaus Wernigerode ). High school students who professed to be a member of the Church were often expelled from school, sometimes shortly before graduation. The church student communities at the universities were severely hindered.

Increase in norms

Against this crisis-ridden national background, the increase in labor standards ( i.e. the work to be performed for wages) was perceived as a provocation and a foreseeable deterioration in the living conditions of the workers. By raising labor standards by ten percent by June 30, Walter Ulbricht's 60th birthday , the Central Committee wanted to counter the economic difficulties. Issued as a recommendation, it was in fact an instruction that was to be carried out in all state- owned companies and would ultimately have resulted in a wage reduction. The Central Committee of the SED decided to raise the standard on May 13 and 14, 1953, and the Council of Ministers confirmed it on May 28.

New course

In the meantime, the leadership of the Soviet Union had made its own thoughts on the situation in the GDR and, at the end of May, conceived the measures to heal the political situation in the GDR , which were communicated to an SED delegation appointed to Moscow on June 2, 1953. SED politicians asked for a more cautious and slower change of course, for example, from the new High Commissioner Vladimir Semjonow - the highest-ranking Soviet representative in the GDR who was de facto superior to the GDR leadership - with the sentence “In 14 days you might not be a state more have refused.

On June 11, the “New Course” of the Politburo was finally announced in the SED central organ Neues Deutschland : It certainly contained self-criticism. Some measures to build socialism have been withdrawn. Tax and price increases should be repealed. Craftsmen, retailers and private industrial companies could request the return of their shops and businesses. Middle farmers got their previously confiscated agricultural machinery back. All arrests and convictions should be reviewed. The electrical current was no longer switched off.

The fight against the young community was stopped. Pastors and church workers have been released from custody, and confiscated buildings have been returned. Pupils expelled from secondary school because of their religious beliefs had to be re-accepted and admitted to high school. For the 5th German Evangelical Church Congress , which took place shortly afterwards in Hamburg, interzone passes were generously issued and special trains were even used.

Above all, the remaining middle class as well as the farmers would benefit from the “new course”. The rise in labor standards continued, which led to the first expressions of discontent among the workers. The population in the villages was told that expropriated farmers would get their land back, detainees would be released from prisons and GDR refugees could return with impunity. Furthermore, the unilateral promotion of agricultural production cooperatives should be ended and unprofitable LPGs should be dissolved again. The population saw this change of course as an admission of the government's ineptitude.

On June 14th, the article It is time to put the mallet aside was published in Neues Deutschland, which critically examined the implementation of the increase in standards on the basis of a report on the construction industry without, however, generally calling it into question. This article, especially the latter, received a lot of attention and, in conjunction with an article published two days later in the trade union newspaper Tribüne , which justified the ten percent increase in norms as "completely correct", triggered protests.

course

From Friday, June 12, 1953

Before the unrest in the cities, resistance campaigns began in many villages as early as June 12th. In more than 300 communities with fewer than 2,000 inhabitants, there were spontaneous protests in which, for example, flags were burned and the mayors and other SED officials were deposed, beaten and, in individual cases, thrown into cesspools . Farmers also organized protests in various district towns such as Jessen and Mühlhausen and took part in the demonstrations in the centers, including in Berlin. The Ministry of State Security later noted that “the fascist attempted coup on June 17, 1953 [showed] that the class opponent was concentrating his forces on the country”.

Tuesday June 16, 1953

On Tuesday, June 16, the first work stoppages occurred at two major construction sites in Berlin, Block 40 in Stalinallee and the new hospital building in Berlin-Friedrichshain , which had been informally agreed on the previous days. An initially small protest march formed from both construction sites, which quickly expanded - mainly to include more construction workers - on the way to the house of the trade unions of the Free German Trade Union Federation (FDGB) and on to the government seat on Leipziger Strasse .

After the union leaders refused to listen to the workers, the demonstration in front of the government building was informed that the Politburo had decided at noon to withdraw the increase in standards. In the meantime, however, the demands of the crowd have moved far beyond this specific reason for protest.

In an increasing politicization of the slogans, among other things, the resignation of the government and free elections were called for. The crowd then moved in a steadily growing march through the city center back to the construction sites on Stalinallee, with chants and a captured loudspeaker truck calling for a general strike on the way and calling the population to a protest meeting at 7 a.m. on Strausberger Platz the following day .

On the evening of June 15, the RIAS had already reported in detail about strikes in East Berlin's Stalinallee. Since midday on June 16, he reported extensively on the strikes and protests. Representatives of the strike movement went to the station and spoke directly to the then editor-in-chief Egon Bahr to call the general strike on the radio. The broadcaster RIAS, however, denied the strikers this opportunity. On June 17th, the Berlin DGB chairman Ernst Scharnowski called for the first time through the RIAS that East Germans should go to their “Strausberger Platz everywhere”. Despite a relatively cautious presentation of the events on the radio, it can be assumed that the reports made a decisive contribution to the fact that the news of the protests in the capital spread extremely quickly throughout the GDR.

Wednesday June 17th 1953

On the morning of June 17th something broke out throughout the GDR that would later go down in history as the June 17th uprising . The workforce, especially large companies, went on strike at the beginning of the morning shift and formed demonstration marches that were directed to the centers of the larger cities. In the days of the uprising, the Western media and probably most protesters were not yet aware of the national dimension of the protests. The RIAS reported almost exclusively from Berlin. In fact, according to recent research, there were strikes, rallies or violence against official persons or institutions in well over 500 locations in the GDR.

The insurgents occupied 11 district council buildings, 14 mayor's offices, 7 district leaderships and one district leader of the SED. Furthermore, nine prisons and two service buildings of the Ministry for State Security (MfS) as well as eight police stations, four People's Police District Offices (VPKA) and one department of the District Authority of the German People's Police (BDVP) were stormed. More than twice as many facilities were pressed, but the occupation failed.

The focus was on Berlin and the traditional industrial regions, such as the “ chemical triangle ” around Halle , but also in the district capitals Magdeburg , Leipzig and Dresden . The number of those involved in the protest cannot be precisely determined; figures vary between 400,000 and 1.5 million people. The various protests took place very spontaneously, there was practically no target planning beyond the day, nor any real executives who would have directed the uprising nationwide. In addition to work stoppages and demonstrations, prisons were stormed and prisoners were liberated in several places. In Gera there was a storming of the Stasi investigation detention center Amthordurchgang , and detainees were released. Around 20,000 people demonstrated in the city center with the support of miners from the Wismut districts. Arson broke out in Berlin , the most spectacular being the fires at the flagship HO department store Columbushaus and the Haus Vaterland restaurant on Potsdamer Platz in Berlin. In Berlin alone there were 46 injured police officers, 14 of them seriously, as well as destruction worth over 500,000 marks.

The police were overwhelmed by the extent of the events, in some cases people's police ran over to the demonstrators. There were bloody clashes between demonstrators and the police, especially in East Berlin. In Rathenow angry insurgents beat up the Stasi informant Wilhelm Hagedorn , who died as a result. In Niesky, employees of the state security were locked in a dog kennel and in Magdeburg the demonstrators forced a police officer to lead their procession in scanty clothes.

In the Görlitz and Niesky districts, the SED regime was eliminated for a few hours. Due to the particular demographic structure of these circles, the protest movement escalated into a political uprising, which led to the local rulers being temporarily disempowered. As a border town, Görlitz had to integrate a high proportion of displaced persons. After Berlin and Leipzig, the city was the most densely populated area in the GDR and there was a high level of unemployment, especially among young people, women and the severely disabled, which was accompanied by a housing shortage well above the GDR average. In addition, the Görlitz community was made more difficult by the division of their city and the border security measures of the GDR against the “Polish Brotherhood”. Likewise, most Görlitzers did not accept the Oder-Neisse border according to the contract of July 6, 1950. The non-urban political leadership had set in motion a radical wave of expropriation since 1952, which had led to a drastic decline in the number of self-employed. The number of people who fled the republic had also risen since October 1952 .

The GDR government fled under the protection of the Soviet authorities to the building of the former fortress pioneer school in Berlin-Karlshorst .

At 2 p.m., a statement by Prime Minister Otto Grotewohl was broadcast on GDR radio : it explicitly stated once again that the norms would be withdrawn. The uprising, however, was "the work of provocateurs and fascist agents of foreign powers and their accomplices from German capitalist monopolies". He called on all “workers and honest citizens” to help “seize the provocateurs and hand them over to the state organs”. This representation of the events as an externally staged counter-revolutionary coup attempt already corresponded to the later official reading of June 17 in GDR historiography. However, according to some historians, the uprising could not have taken place without external influences. This is how the former RIAS employee, Egon Bahr, sums up :

“Precisely because there had been no organization, it was indisputable that the RIAS, without wanting to be, had become the catalyst of the uprising. Without the RIAS, the uprising would not have happened. The SED's hatred of the RIAS was understandable. The conspiracy theory, the allegations that we brought this about on purpose: nonsense. As in Hungary and Poland later, the West was itself surprised. "

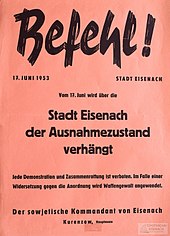

Suppression of the uprising and martial law

The Soviet authorities reacted by imposing a state of emergency for 167 of the 217 districts of the GDR . Around 1 p.m., the military commander of the Soviet sector of Berlin, Major General Pyotr Dibrowa , announced the state of emergency in East Berlin, which was not lifted again until July 11, 1953. With this proclamation of martial law, the Soviet Union officially took over governance over the GDR again. The Soviet troops, which were moving into other parts of the GDR as early as 10 am in Berlin, delayed around noon or afternoon, demonstrated their presence above all, because the uprising quickly lost momentum with the arrival of the tanks; there were no major attacks on the military. A total of 16 Soviet divisions with around 20,000 soldiers and around 8,000 members of the Barracked People's Police (KVP) were deployed.

Although the Soviet authorities brought the situation largely under control on June 17th, protests continued in the following days, especially on June 18th. In individual companies, they lasted into July. Strikes took place on July 10 and 11 at Carl Zeiss in Jena and on July 16 and 17 at the Buna plant in Schkopau . The strength of June 17, 1953, however, was no longer even close.

In a first wave of arrests, the police, the MfS and the Soviet Army arrested mainly so-called " provocateurs ".

Victim

According to the results of the project The Dead of the People's Uprising of June 17, 1953 , sources have proven 55 fatalities. About 20 more deaths are unexplained.

On June 17 and the days after, 34 demonstrators and spectators were shot dead by People's Police and Soviet soldiers or died as a result of gunshot wounds. Seven people were executed after the death sentences of Soviet and GDR courts . Four people died and four people killed themselves in custody as a result of the detention conditions. A protester died of heart failure while storming a police station. In addition, five members of the GDR security organs were killed. So far there has been talk of 507 deaths in the west and 25 in the GDR. Random victims such as the 27-year-old agricultural doctoral student Gerhard Schmidt from Halle who was fatally hit by a stray police bullet stylized the SED as an “anti-fascist” martyr, although his family was expressly against it.

The Soviet troops also set up trial courts from June 17 to 22, 1953 , of which 19 insurgents were sentenced to death and shot , including Alfred Diener from Jena, Willi Göttling from West Berlin and Alfred Dartsch and Herbert Stauch from Magdeburg. Hundreds have been sentenced to forced labor in Siberia. Around twenty Red Army soldiers who allegedly refused to shoot the rebels are said to have been executed. According to other research, there is no evidence that this insubordination and the executions took place.

On March 5, 1954, the attorney general of the GDR, Ernst Melsheimer , submitted a report to Hilde Benjamin , Minister of Justice, on "the trial of the provocateurs of the June 17, 1953 putsch", the following for the period up to the end of January 1954 Judgments on a total of 1,526 defendants broken down:

- 2 defendants were sentenced to death: Erna Dorn , Ernst Jennrich

- 3 defendants received a life sentence: Lothar Markwirth ( District Court Dresden ), Gerhard Römer (District Court Magdeburg) and Kurt Unbehauen (District Court Gera)

- 13 defendants, including the Dresden Wilhelm Grothaus (1893–1966) and Fritz Saalfrank (1909–199?), Were sentenced to prison terms of ten to fifteen years.

- 99 defendants received prison sentences of between five and ten years.

- 824 defendants received prison terms ranging from one to five years.

- 546 defendants received prison terms of up to one year.

- 39 defendants were acquitted.

A further 123 criminal proceedings had not yet been concluded at the end of January 1954. It can be assumed that the GDR courts sentenced a total of around 1,600 people in connection with the June uprising.

Those convicted of June 17 were marked with a yellow "X" in detention centers. Because of the poor medical care, the harassment of the guards and the inadequate occupational safety in the penitentiaries, many "Xers" suffered serious health problems. The wives of the convicts were often advised to divorce or threatened with the removal of their children.

The SED also used the uprising to discipline its own comrades. For example, the members who came mainly from the former SPD and who represented moderate political views were removed from the party. The Justice Minister Max Fechner , who wanted to moderate the criminal justice system after June 17, was removed from his position on July 14, 1953, excluded from the party for anti-party and subversive behavior and imprisoned under inhumane conditions. Party functionaries and members of the People's Police were also punished for whom the SED leadership accused them of “conciliatory, capitulant and non-combative behavior”. As a result of these purges, radical communists like Erich Mielke , Hilde Benjamin and Paul Fröhlich shaped future politics in the GDR. Rudolf Herrnstadt , editor-in-chief of the daily newspaper Neues Deutschland , was made jointly responsible for the events on June 17, 1953. He was dismissed from his job and, together with Wilhelm Zaisser, expelled from the SED.

June 17th and the SED

For the SED leadership, the events of June 17, 1953 were a traumatic experience. The main target group of their politics, the working class, had massively withdrawn their trust in the SED. In particular, the employees of the large state and SAG companies had stopped working and took to the streets with their political demands. The SED found none of the demands worthy of open discussion. Immediately after the uprising, the SED began to consciously cover up the causes. In Otto Grotewohl's speech at the 15th Central Committee Plenum (July 24-26, 1953), the uprising - without any evidence to prove it - turned into a "fascist attempted coup " directed by the West . The real problem of the GDR, the “functional deficits of a dedifferentiated society”, was not solved by the “new course” announced on June 9, 1953. After the crackdown by Soviet tanks, it became clear to those involved in the strike and demonstrations that the SED regime was part of the Soviet empire and was not up for grabs. In the SED itself, "party purges" were the order of the day.

GDR internal representation of the events

Presentation of the events by the GDR media

The state-controlled press and radio vehemently denied any self-infliction of the unrest of June 17, 1953 in the form of dissatisfaction among the population with the political situation, depressing supply shortages and considerable increases in standards for the workers. According to this, the uprisings of June 17, 1953 were allegedly deliberately provoked events initiated by the “West”. The GDR radio journalist Karl-Eduard von Schnitzler put it this way: “[…], while some of Berlin's workers and employees misused the good faith that they had to respond to gross errors in raising the standard with work stoppages and demonstrations, people were paid Provocateurs, an attack on freedom from the scraps of the West Berlin underworld, an attack on existence, on jobs, on the families of our working people. "

Representation of the events through the GDR historical science

A book on the history of the GDR published in 1974 under the direction of the historian and unofficial employee of the state security Heinz Heitzer at the Academy of Sciences of the GDR described the popular uprising as a "counterrevolutionary coup attempt": The Soviet troops stationed in the GDR had "determined Intervene ”thwarted the“ intentions of imperialism ”. The use of Soviet armed forces was described as an action in the "spirit of proletarian internationalism". The majority of the "misguided working people" soon turned away from the putschists, their devastation and the openly proclaimed counterrevolutionary goals of the putschists and began to recognize that they had acted against their own interests.

Reactions

Apart from the Soviet Union, no other states intervened in the uprising. The consequences could have been serious, because according to the current treaties, the American occupiers had no right to penetrate the Soviet sector of Berlin.

Federal Republic of Germany

Contemporary witnesses

When Ernst Reuter , the Governing Mayor of West Berlin, who was in Vienna at the European City Council, asked the Americans to provide him with a military aircraft for the fastest return flight, he was told that this was unfortunately not possible. Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer traveled to Berlin on June 19 to commemorate the dead.

On the occasion of the memorial service, which took place with great sympathy from the West Berlin population, the RIAS editor Hanns-Peter Herz judged on June 19, 1953: “Bonn did not behave generally across Germany on this issue, the Prussian potato fields were not as interesting as the vines at Rhine."

Franz Josef Strauss described the behavior of the federal government in his memoirs: “In Bonn there was no possibility of serious action. There were declarations, demonstrations of sympathy, appeals to the victorious powers - what else should the federal government do? At that time one became aware of the whole German impotence again. "

Commemoration

On June 22, 1953, five days after the outbreak of the uprising, the Berlin Senate named the Berliner Strasse and Charlottenburg Chaussee between the Brandenburg Gate and the S-Bahn Tiergarten, later the Ernst-Reuter-Platz in Strasse des 17. Juni to . By law of August 4, 1953, the Bundestag declared June 17 to be the “ Day of German Unity ” and a public holiday. The Federal President declared it on June 11, 1963, in addition to the “National Day of Remembrance of the German People”. In 1990, the Unification Treaty on German reunification set October 3rd as the day of the accession of the German Democratic Republic to the Federal Republic of Germany, the Day of German Unity and a public holiday. June 17th only retained its status as a memorial day . In 2016, Thuringia declared June 17th a day of remembrance for the victims of the SED injustice .

In 1964 the bridge of June 17th in Hamburg got its name.

United States

In the United States , people initially thought of a trick by the USSR with regard to the uprising : legitimized by the uprising, it wanted to relocate armed groups to Berlin to crush it, so that it could take the entire city. For a time, the demonstrations were thought to be events staged by the GDR government that got out of control.

United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom , Winston Churchill , was critical of the uprising, as it threatened his initiative for a new four-power conference. He told the Soviet government that it was right in putting down the uprising.

Soviet Union

The uprising of June 17, 1953 intensified the struggle for his successor that had broken out in the Soviet Union since Stalin's death on March 5, 1953. The group around the powerful Minister of Internal Affairs ( MWD ) Lavrenti Beria (1899–1953), who ordered the immediate suppression of the uprising, favored a release of the GDR in the interests of international relaxation and in the hope of German economic cooperation. The victorious faction around Nikita Khrushchev , on the other hand, feared that the uprising would serve as a model for other Eastern European states ( Poland , Czechoslovakia , Hungary ) or for nations within the Soviet Union ( Ukraine , Baltic States ). As a result of this policy and the previous accession of the Federal Republic to NATO , the Warsaw Treaty was ratified in 1955 , which bound the Eastern European states and the GDR militarily to the Soviet Union and strengthened the division of Europe.

Yugoslavia

On June 28, 1953, the Yugoslav party newspaper Borba published an editorial by the leading communist theorist Edvard Kardelj , in which the uprising of June 17 was described as "the most important event after the Yugoslav resistance of 1948". Kardelj recognized in the strikes and demonstrations “the character of a real revolutionary mass action by the working class against a system that calls itself 'socialist' and 'proletarian'.” He further wrote: “The driving force of these events is not fundamentally the national moment; it is not just a problem for the Germans against a foreign occupation. No, it is above all a matter of the class protest of the German worker against the state capitalist conditions, which the occupation forced on him as 'socialist' and 'proletarian' in the name of a 'socialist messianism', but which he did not call 'proletarian'. still recognized as 'socialist'. And precisely therein lies the historical significance of these events. "

Poland

In Warsaw there was great concern about the events in the GDR. The Polish leadership viewed the uprising as a political warning signal. She feared that similar social protests would also take place in Poland, mainly because labor standards were raised much more drastically than in the GDR. They also expected unrest among the Germans who remained in Poland, as they received independent information from German-language broadcasters. The PVAP also feared that the Polish population in western Poland, i.e. H. in the former East German territories, would react with concern as a result of the political events in the GDR. An analysis written by the PVAP on June 23, 1953 highlighted: "[...] that the mistakes made by the leadership of our sister party undoubtedly provided a basis for that provocation". Specifically, the SED's mistake was the excessive increase in labor standards, the accelerated course in building socialism, the ignorance of the needs of the people and the turning away from German reunification.

Expansion of the surveillance, discipline and suppression apparatus after the uprising

In order to stabilize the regime, after the uprising, the SED pushed for the expansion of the oppressive apparatus, which eventually encompassed almost the entire population. To this end, the Stasi was tied even more closely to the SED and mass organizations and other institutions were entrusted with the surveillance and suppression of system critics. In order to be able to fight civil unrest more effectively and to better protect objects, the SED founded a paramilitary organization in large factories and administrations , the so-called " working class combat groups ". For the early detection and suppression of further opposition unrest, the police forces were strengthened and better equipped and district, district and city operations management was formed, which should cooperate closely with the SED leadership, the barracked people's police , people's police and Stasi . At the district, district and company party leadership level, most of the leading functionaries were replaced.

Protagonists

- Max Fechner (1892–1973): Minister of Justice, turned against the prosecution of striking workers and was sentenced to eight years in prison;

- Hilde Benjamin (1902–1989): replaced Fechner as the new Minister of Justice and ensured harsh judgments;

- Erna Dorn (1911–1953): beheaded as an alleged ringleader;

- Max Fettling (1907–1974): construction worker, union official on the hospital construction site in Friedrichshain. He signed the letter to the government of the GDR dated June 15, 1953, which he personally handed to Otto Grotewohl and which said: “Our workforce is of the opinion that the ten percent increase in standards is a great hardship for us. We demand that this increase in standards be refrained from on our construction site. ”He was arrested as a“ strike leader ”on June 18, 1953 and sentenced to ten years in prison. In 1957 he was released on parole. A square in Berlin-Friedrichshain has been named after him since 2003 .

- Georg Gaidzik (1921–1953): People's Policeman, suffered fatal gunshot wounds;

- Gerhard Händler (1928–1953): People's Policeman, sustained fatal gunshot wound;

- Ernst Jennrich (1911–1954): sentenced to death on instructions from Hilde Benjamin and beheaded;

- Günter Mentzel (1936–2007): construction worker, 16-year-old strike leader of Block 40 on Stalinallee;

- Otto Nuschke (1883–1957): Deputy Prime Minister, was pushed to West Berlin by demonstrators on June 17, 1953, from where he returned to the GDR two days later;

- Paul Othma (1905–1969): Electrician, spokesman for the strike committee in Bitterfeld , sentenced to twelve years in prison, died as a result of eleven and a half years in prison .;

- Karl-Heinz Pahling (1927–1999): construction worker, 26-year-old strike leader, ten years in prison;

- Otto Reckstat (1898–1983): symbolic figure of the workers' uprising on June 17, 1953 in Nordhausen , eight years imprisonment;

- Walter Scheler (1923–2008): accountant, took part in the uprising, arrested by Soviet occupation forces and sentenced to 25 years in a camp in Weimar one day later and pardoned in 1961;

- Gerhard Schmidt (1926–1953): shot dead by the police as a passer-by who happened to be present and exploited by the SED as one killed by the rebels;

- Fritz Selbmann (1899–1975): GDR minister, tried in vain on June 16 to persuade the workers to give up the strike;

- Johann Waldbach (1920–1953): Employee of the Ministry for State Security of the GDR, suffered a fatal head shot.

Artistic reception

Bertolt Brecht processed the events of June 17 in his poem The Solution with the famous closing sentence: "Would it be there / Wouldn't it be easier, the government / dissolved the people and / chose someone else?"

The solution is part of the Buckower Elegies collection with other poems that Brecht wrote mainly in the summer of 1953. At the same time his poem The Bread of the People was written : "Justice is the bread of the people [...]"

Brecht and his attitude towards the events of June 17th are the subject of the "German tragedy" The plebeians rehearse the uprising that Günter Grass published in 1966.

Stefan Heym describes the events in Berlin in his novel 5 Days in June . It was first published in 1974 in the FRG and only in 1989 in the GDR.

Stephan Hermlin portrays the alleged concentration camp guard and ringleader Erna Dorn in the story Die Kommandeuse . It first appeared in 1954 in the journal Neue Deutsche Literatur .

Final considerations

The uprising of June 17, 1953 is part of the tradition of progressive, all-German historical events such as the March Revolution of 1848/49 or the November Revolution of 1918/19, which were followed by social developments such as the 1968 movement and the peaceful revolution of 1989/90. However, the international constellation in 1953 did not allow any revolutionary change in Germany ( see: Cold War ).

However, the previous reconstructions of June 17, 1953 show that there was no unified uprising that took place in a similar manner in all places. Instead, the spontaneous surveys took an extremely different regional course. In the industrial metropolitan areas, such as Leipzig, Halle, Bitterfeld, Magdeburg, Dresden and Görlitz, the uprising achieved a higher degree of organization than in East Berlin. While the Berlin construction workers mainly submitted social and economic demands, such as the withdrawal of the standard increases or the reduction of the cost of living, the central strike leadership of the Bitterfeld district wrote the following program, which they sent to the government by telegram:

- Resignation of the so-called German Democratic Government, which came to power through electoral maneuvers

- Formation of a provisional government from the progressive working people

- Approval of all major parties in West Germany

- Free, secret, direct elections in four months

- Release of all political prisoners (direct political, so-called economic criminals and denominational persecution)

- Immediate abolition of the zone border and withdrawal of the People's Police

- Immediate normalization of living standards

- Immediate abolition of the so-called People's Army

- No reprisals against a striker

So far little research has been done on public protests that have formed in the countryside, in the villages and in the communities. Examples are the events in the villages of Zodel or Ludwigsdorf in the Görlitz area.

Like the insurgents, the local SED officials acted differently. So ordered z. B. Paul Fröhlich told Leipzig VP and MfS members to use their firearms between 1 p.m. and 2 p.m., although the state of emergency was only declared at 4 p.m. As a result of this order, 19-year-old Dieter Teich and 64-year-old pensioner Elisabeth Bröcker were shot in the early afternoon of June 17 . Thousands of people from Leipzig followed the funeral procession with the nineteen-year-old's corpse laid out in front of him, which ran from Dimitroffplatz via Georgiring to the main train station. On the other hand, on June 16, officials like Fritz Selbmann in East Berlin or on June 17, Otto Buchwitz in Dresden, tried to persuade the strikers to resume their work. The SED district leadership of Karl-Marx-Stadt promised the insurgents to respond to their social demands, so that the June uprising in this district was more restrained than elsewhere. SED functionary Fred Oelßner , who was in Halle on business, constituted - initially without any support from Berlin - a district operations command (consisting of the heads of the district SED, MfS, VP and KVP institutions as well as the Soviet armed forces) with the aim of Quickly and forcibly put down rebellion. In contrast, Fritz Selbmann, who was sent from Berlin to the Dresden district on June 17, received official instructions from Walter Ulbricht.

The various strike lines tried to prevent property damage and violence against people, although they usually had little influence on what was happening outside their workplaces. They were also concerned about strict adherence to democratic rules and avoided anti-Soviet slogans because they were aware that no social change would be achieved in the GDR against the Soviet Union. In some cities (e.g. Leipzig, Schkeuditz, Görlitz), inter-company organizational structures developed during the uprising, which coordinated the mass demonstrations that had already arisen spontaneously. In other cities (e.g. Dresden, Halle) the mass demonstrations developed dynamically and independently of the strike leadership. The proportion of former NSDAP members in the strike leadership was - in contrast to the later SED propaganda - very low. Most of the strike activists were non-party, including many excluded SED members, often including former Social Democrats. Leading actors in the strike leadership were often older workers, technical or commercial employees who could fall back on their experience in the political and union struggle before 1933.

However, outstanding protagonists of the uprising, such as the Berlin brigadier Alfred Metzdorf, the Görlitz pensioner Max Latt, the self-employed photographer Lothar Markwirth and the body builder Erich Maroske from Niesky or the strike leaders of VEB ABUS Dresden Wilhelm Grothaus and Fritz Saalfrank could not stand as leaders of the whole Profiling uprisings. The uprising of June 17 was a spontaneous mass uprising or a collective popular movement without central leadership and without a uniform strategy. Some historians see this as a cause for the failure of the uprising.

The participation of young people in the uprising was very high. Among the ten protesters killed or shot dead on the streets of the Leipzig district, there were seven young men between the ages of 15 and 25. Because many young people had taken part in the destruction of institutions and symbols of the SED, the Stasi and the FDJ, the proportion of those arrested and convicted was particularly high. Of those convicted by the Dresden District Court up to July 23, 1953, 16% were between the ages of 14 and 18, 22% were in the 18 to 20 age group and 17% were between 20 and 25 years of age. That is, more than half of those convicted were young people. This was also due to the fact that many men born before 1928 or 1929 had died in the war; some of these vintages were clearly decimated.

The weekly newspaper Die Zeit commemorated eight Berlin victims in an obituary notice on June 25, 1953, six of whom were between 14 and 25 years old.

The uprising of June 17, 1953 made everyone in the GDR realize that the SED regime was only maintained with the help of Soviet weapons. In order to rule out another uprising, the Stasi built up a dense network of surveillance and spying over the next few years. Ulbricht finally put an end to the “voting with the feet” of broad sections of the population with the construction of the Berlin Wall on August 13, 1961. In the years that followed, GDR social policy favored workers in the heavy and construction industry with wage increases and bonuses. On the other hand, care for retirees and the disabled remained limited to a minimum. The opposition that existed before 1989 was formed from all walks of life.

literature

Non-fiction

- Arnulf Baring : June 17, 1953 . Federal Ministry for All-German Issues, Bonn 1957 (also dissertation in English, Columbia University , New York 1957).

- Hans Bentzien : What happened on June 17th? Third revised and expanded edition. Edition Ost, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-360-01843-4 .

- Stefan Brant ( pseudonym of Klaus Harpprecht ), Klaus Bölling : The uprising . Prehistory, history and interpretation of June 17, 1953. Steingrüben, Stuttgart 1954.

- Peter Bruhn: June 17, 1953 Bibliography . 1st edition. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-8305-0399-7 .

- Bernd Eisenfeld , Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk , Ehrhart Neubert : The suppressed revolution. The place of June 17th in German history . Edition Temmen, Bremen 2004, ISBN 3-86108-387-6 .

- Roger Engelmann , Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk (ed.): Popular uprising against the SED state. An inventory for June 17, 1953 (= The Federal Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the former German Democratic Republic. Analyzes and documents. 27). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-525-35004-X .

- Roger Engelmann (ed.): The GDR in view of the Stasi 1953. The secret reports to the SED leadership . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-525-37500-6 .

- Karl Wilhelm Fricke , Ilse Spittmann-Rühle (Ed.): June 17, 1953. Workers' uprising in the GDR . 2nd Edition. Edition Deutschlandfunk Archive, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-8046-0318-1 .

- Torsten Diedrich : Arms against the people. June 17, 1953 in the GDR . Published by the Military History Research Office, Oldenbourg, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-486-56735-7 .

- Torsten Diedrich, Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk (Hrsg.): State foundation on installments ?. Effects of the popular uprising in 1953 and the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961 on the state, the military and society (= military history of the GDR . Vol. 11). On behalf of the Military History Research Office and the Federal Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the former GDR, Links, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-86153-380-4 .

- András B. Hegedüs, Manfred Wilke (ed.): Satellites after Stalin's death. The "New Course" - June 17, 1953 in the GDR - Hungarian Revolution 1956 . Oldenbourg Akademieverlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 978-3-05-003541-3 .

- Haruhiko Hoshino: Power and Citizens. June 17, 1953 . Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-631-39668-6 .

- Hubertus Knabe : June 17, 1953. A German uprising . Ullstein Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-548-36664-3 .

- Guido Knopp : The uprising June 17, 1953 . ISBN 3-455-09389-2 .

- Volker Koop : June 17th. Legend and reality . Siedler, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-88680-748-7 .

- Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk , Armin Mitter , Stefan Wolle : The day X - June 17, 1953. The "internal founding of the state" of the GDR as a result of the crisis in 1952/54 (= research on GDR history. 3). Ch. Links, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-86153-083-X .

- Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk: June 17, 1953. Popular uprising in the GDR. Causes - processes - consequences . Edition Temmen, Bremen 2003, ISBN 3-86108-385-X .

- Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk: June 17, 1953 - history of an uprising . Beck, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-64539-6 .

- Ulrich Mählert (Ed.): June 17, 1953. An uprising for unity, law and freedom . Dietz, Bonn, ISBN 3-8012-4133-5 .

- Klaus-Dieter Müller, Joachim Scherrieble, Mike Schmeitzner (eds.): June 17, 1953 in the mirror of Soviet intelligence documents. 33 secret MWD reports about the events in the GDR (= time window . Vol. 4). Leipziger Universitätsverlag, Leipzig 2008, ISBN 978-3-86583-272-6 .

- Jörg Roesler : "Piecework is murder, raising standards is the same". A tradition of the economic struggle of the German working class and June 17, 1953 . Yearbook for Research on the History of the Labor Movement , Volume II / 2004.

- Heidi Roth: June 17, 1953 in Saxony . Ed .: Hannah Arendt Institute for Research on Totalitarianism e. V. at the Technical University of Dresden. Special edition for the Saxon State Center for Political Education.

- Edgar Wolfrum : Historical Politics and the German Question. June 17th in the national memory of the Federal Republic (1953–1989) . In: History and Society . tape 24 , 1998, pp. 382-411 .

- Andreas H. Apelt, Jürgen Engert (ed.): The historical memory and June 17, 1953 . Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Halle (Saale) 2014, ISBN 978-3-95462-225-2 .

Fiction

- Stephan Hermlin : The commanding officer . In: New German Literature . tape 2 , no. 10 , 1954, pp. 19-28 .

- Stefan Heym : 5 days in June . 1st edition. Bertelsmann, Gütersloh 1974, ISBN 3-570-02974-3 .

- Erich Loest : Summer thunderstorm . Steidl, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 978-3-86521-177-4 .

- Titus Müller : The D-Day . Blessing, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-89667-504-0 .

youth book

- Petra Milz: The short freedom. Berlin 1953. Hase and Igel, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-86760-196-2 .

Web links

- History - popular uprising of June 17, 1953 on bstu.de.

- Literature on uprising from June 17, 1953 in the catalog of the German National Library

- MfS Lexicon: People's uprising in June 1953 and the MfS

- Collection of Stasi documents on the popular uprising of June 17, 1953 in the Stasi media library of the BStU

- June 17, 1953. Extensive bibliographical database of international literature on the events of June 1953

- Ehrhart Neubert : The uprising of June 17, 1953 .

- June 17, 1953: The uprising in the GDR. Chronology of the Bavarian Radio .

- June 17, 1953: Uprising in the GDR. Calendar sheet of Deutsche Welle .

- June 17th was not a revolution . Günter Grass in Spiegel Online , June 16, 2003.

- Young people during the 1953 popular uprising. Interviews, documents, photos and videos on jugendopposition.de

- June 17th and the GDR opposition . In: Horch und Guck 12th vol., Issue 42 (2/2003), pp. 18-21.

- Federal Archives: June 17, 1953.

- Popular uprising in the GDR on June 17, 1953. On the information portal for political education.

- Resistance in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. Texts about June 17, 1953 in Mecklenburg and Western Pomerania.

Individual evidence

- ^ Speech by the President of Parliament. In: In Parliament. RBB, June 17, 2010, archived from the original on February 11, 2013 ; Retrieved June 19, 2012 .

- ↑ Michael Lemke: June 17, 1953 in the history of the GDR. In: From Politics and Contemporary History. BpB , June 2, 2003, accessed June 19, 2012 .

- ↑ In the Soviet Union , the forced laborers in the Vorkuta camp went on strike from July 22 to August 1, 1953 , and anti-Stalinist uprisings also broke out in the Norilsk nickel works in 1953/1954. On June 28, 1956, 15,000 workers at the Stalin plant in Poznań (Zakłady Metalowe imienia Józefa Stalina w Poznaniu - ZISPO) stopped their work - the Poznan Uprising - and on October 23, 1956, the Hungarian people's uprising began . The “ Prague Spring ” of 1968 in Czechoslovakia , the uprising of December 1970 , the August strikes of 1980 in Poland and the political events of 1989/1990 in Central and Eastern Europe also follow the anti-Stalinist model of June 17, 1953.

- ↑ Torsten Diedrich, Rüdiger Wenzke: The camouflaged army. History of the barracked people's police of the GDR 1952–1956. Links, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-86153-242-5 , p. 225

- ↑ military expenditure including occupation costs; Torsten Diedrich, Armament Preparation and Financing in the Soviet Zone / GDR 1948–1953; in Bruno Thoss; Create people's army - without shouting !; Studies on the beginnings of a "covert armament" in the Soviet Zone / GDR, Munich 1994, ISBN 978-3-486-56043-5 , pp. 272–336, here pp. 329, 332.

- ↑ Rüdiger Wenzke, Torsten Diedrich: The camouflaged army. History of the Barracked People's Police of the GDR 1952–1956 , Ch. Links, Berlin 2001, ISBN 978-3-86153-242-2 ; P. 311/312.

- ↑ Christoph Buchheim : On the other hand, the problem of excess purchasing power could only be temporarily resolved by a new money exchange campaign in 1957 . In: Deficiencies inherent in the planned economy , economic background to the workers' uprising of June 17, 1953 in the GDR, Munich, quarterly books for contemporary history 1990, issue 3, p. 418 ff, here p. 433 ( PDF ).

- ↑ “The bad harvest of 1952 had an even more serious impact than the shortage of industrially manufactured consumer goods. It was a consequence of bad weather conditions, but also of the socialization campaign in agriculture, carried out for ideological reasons, which had caused many farmers to flee. The shortage of food for the population was further exacerbated by the creation of larger state reserves and the increasing demands of the military. In any case, a food crisis broke out in the GDR in 1953, which was comparable to the situation in the early post-war period. "Christoph Buchheim: Economic Background of the Workers' Uprising of June 17, 1953 in the GDR , Munich, Quarterly Issues for Contemporary History 1990, Issue 3, p. 415 –433, here p. 428.

- ↑ Armin Mitter: Die Bauern und der Sozialismus , in: Der Tag X, June 17, 1953: the "inner state foundation" of the GDR as a result of the crisis 1952–1954 , Ch. Links Verlag, 1996, ISBN 978-3-86153- 083-1 , pp. 75 ff, here pp. 80–82.

- ↑ See Wilfriede Otto (ed.): "The construction workers [...] do not recognize the 10% increase in standards dictated to them." In: Yearbook for Research on the History of the Workers' Movement , Volume II / 2003.

- ↑ a b Jens Schöne: The Agriculture of the GDR 1945–1990 , State Center for Political Education Thuringia, 2005, pp. 28/29

- ^ Ray Furlong: Berliner recalls East German uprising. In: BBC NEWS. June 17, 2003, accessed November 12, 2008 .

- ↑ Peter Bruhn: June 16, 1953 I will never forget ( Memento from April 4, 2013 on WebCite ) (eyewitness report)

- ↑ Egon Bahr recalls: “Do you want the third world war?” . In: Handelsblatt Online , accessed on June 17, 2013

- ↑ June 17th in Thuringia. Jan Schönfelder, Thuringia Journal ( Memento from April 30, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Angelika Holterman: Das divided Leben: Journalist biographies and media structures on the GDR and after , p. 45

- ^ Dead on June 17, 1953. In: June 17, 1953. 2004, accessed on November 12, 2008 .

- ↑ 17juni53.de: Alfred Diener

- ↑ 17juni53.de: Willi Göttling

- ↑ 17juni53.de: Alfred Dartsch

- ↑ 17juni53.de: Herbert Stauch

- ↑ Guido Knopp: The uprising of June 17, 1953 , Hoffmann and Campe Verlag, Hamburg, 1st edition 2003, ISBN 3-455-09389-2 , p. 218 ff.

- ↑ Klaus Schroeder , The SED State. History and structures of the GDR , Bavarian State Center for Political Education, Munich 1998, p. 124

- ^ Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk : June 17, 1953 - popular uprising in the GDR. Causes - processes - consequences , Bremen 2003, p. 257 f .; Torsten Diedrich, Waffen gegen das Volk - or - the power and powerlessness of the military, in: Roger Engelmann / Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk (eds.): People's uprising against the SED state , Göttingen 2005, pp. 58–83, here p. 82

- ^ Heidi Roth: June 17, 1953 in Saxony , special edition for the Saxon State Center for Political Education, Hannah Arendt Institute for Totalitarism Research e. V. at the Technical University of Dresden, p. 67.

- ↑ “Not one of the desires was fulfilled, on the contrary. After the violent suppression of the uprising, the SED intensified its repression through forced militarization of all areas of life and through the expansion of the spying apparatus. ”In: Die Politische Demokratie (6/2003) Volker Koop, Targets and Testimonies of June 17, 1953. Der Wille des whole people, 2003.

- ↑ "A differentiated analysis of the serious, economic, social and political problems of real socialism that existed in reality did not take place until the end of the GDR."; Hermann-Josef Rupieper (Ed.), And the most important thing is unity. June 17, 1953 in the districts of Halle and Magdeburg . LIT 2003, ISBN 978-3-8258-6775-1 , pp. 10-11.

- ^ Dierk Hoffmann: Otto Grotewohl (1894-1964). A political biography. Oldenbourg, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-486-59032-6 , p. 544

- ↑ Kimmo Elo, The systemic crisis of a totalitarian system of rule and its consequences. An updated totalitarian theory using the example of the systemic crisis in the GDR in 1953, LIT 2006, ISBN 978-3-8258-8069-9 , p. 169.

- ^ Andreas Malycha, Peter Jochen Winters The SED: History of a German Party . Beck, Munich, ISBN 3-406-59231-7 , pp. 122, 124/125. Stefan Wolle: The campaign of the SED leadership against "social democracy" . In: Der Tag X, June 17, 1953: the "inner state foundation" of the GDR as a result of the crisis of 1952–1954 . Ch. Links Verlag, 1996, ISBN 978-3-86153-083-1 , pp. 243-277.

- ↑ Karl Eduard von Schnitzler - The attempt on peace has failed. 17juni53.de, accessed on May 28, 2012 .

- ^ Academy of Sciences of the GDR, Central Institute for History (Hrsg.): GDR, becoming and growing. On the history of the German Democratic Republic , Berlin (East) 1974, p. 242 f.

- ↑ See also: Kurt Gossweiler : Background of June 17th , pdf ( Memento of September 28th, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Guido Knopp : Der Aufstand des June 17, 1953 , Hoffmann and Campe Verlag, Hamburg, 1st edition 2003, ISBN 3-455-09389-2 , p. 227.

- ↑ Guido Knopp: The uprising of June 17, 1953 , Hoffmann and Campe Verlag, Hamburg, 1st edition 2003, ISBN 3-455-09389-2 , p. 228.

- ↑ Bundesgesetzblatt 1953 Part I No. 45 of August 7, 1953, p. 778; repealed by the Unification Treaty.

- ↑ Bundesgesetzblatt 1963 I, p. 397 f.

- ↑ Art. 2 Unification Agreement

- ↑ Law on the introduction of a day of remembrance for the victims of the SED injustice of April 29, 2016 ( GVBl. P. 169 , PDF, 1.6 MB)

- ↑ Henning Hoff: Great Britain and the GDR 1955-1973: Diplomacy on detours . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2003, ISBN 978-3-486-56737-3 , p. 43 .

- ↑ See also: “The Case of Beriah. Billing log. The plenum of the Central Committee of the CPSU. July 1953, Stenographic Report ”, edited and translated from Russian by Viktor Knoll and Lothar Kölm, Construction Taschenbuch Verlag Berlin, 1st edition 1993, ISBN 3-7466-0207-6 .

- ^ Heidi Roth: June 17, 1953 in Saxony , special edition for the Saxon State Center for Political Education, Hannah Arendt Institute for Totalitarian Research at the Technical University of Dresden, p. 89

- ^ Heidi Roth: June 17, 1953 in Saxony , special edition for the Saxon State Center for Political Education, Hannah Arendt Institute for Totalitarism Research e. V. at the Technical University of Dresden, p. 90.

- ↑ Gerhard A. Ritter : A historical location. In: Roger Engelmann, Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk (ed.): Popular uprising against the SED state: an inventory of June 17, 1953. Analyzes and documents. Vol. 27. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005. P. 37 f.

- ↑ Werner van Bebber: The uprising did not start on Stalinallee . In: Der Tagesspiegel , June 17, 2010; accessed November 27, 2010 ; see also Klaus Wiegrefe : A German uprising . In: Der Spiegel , February 21, 2006, accessed November 27, 2010

- ↑ Paul Othma tries to curb violence and tries to enforce the strike committee as the new center of power

- ↑ Short biography

- ↑ Guido Knopp, Der Aufstand des June 17, 1953, Hoffmann and Campe Verlag, Hamburg, 1st edition 2003, ISBN 3-455-09389-2 , p. 227

- ^ Bitterfeld telegram to the government of the GDR

- ↑ Guido Knopp: The uprising of June 17, 1953 , Hoffmann and Campe Verlag, Hamburg, 1st edition 2003, ISBN 3-455-09389-2 , p. 10 f.