November Revolution

The November Revolution of 1918/19 led in the final phase of the First World War to the overthrow of the monarchy in the German Reich and to its conversion into a parliamentary democracy , the Weimar Republic .

The deeper causes of the revolution lay in the extreme stresses caused by the war that lasted more than four years, in the general shock at the defeat of the German Empire , in its pre-democratic structures and social tensions as well as in the politics of its elites unwilling to reform. Its immediate trigger, however, was the naval command of the naval war command of October 24, 1918. It provided for the German deep-sea fleet to be sent into a final battle against the British Royal Navy despite Germany's already established war defeat . The mutiny of some ship's crews was directed against this militarily senseless plan, which ran counter to the peace efforts of the Reich government , and this led to the Kiel sailors' uprising . This in turn developed within a few days into a revolution that swept across the empire. It led to the proclamation of the republic in Berlin on November 9, 1918 and to the takeover of power by the majority socialists under Friedrich Ebert . A little later, Kaiser Wilhelm II and all other federal princes abdicated .

The Council of People's Deputies , the provisional revolutionary government, announced elections for a constituent national assembly , which took place on January 19, 1919 and for the first time women had the right to vote . The National Assembly, which met in Weimar, passed the new, democratic Reich constitution on August 11, 1919, which formally brought the revolution to a close.

Goals of the left wing of the revolutionaries that went beyond parliamentarization and were guided by council- democratic ideas failed, among other things, because of the resistance of the SPD leadership. For fear of a civil war , she did not want to completely disempower the old imperial elites in cooperation with the bourgeois parties, but rather to reconcile them with the new democratic conditions. To this end, she entered into an alliance with the Supreme Army Command (OHL) and in January 1919 had the so-called Spartacus uprising violently suppressed, among other things with the help of irregular, right-wing Freikorp troops . In the same way, the provisional government took action against further attempts at council democracy, for example against the Munich soviet republic .

Between November 1918 and May 1919 at least 2,400 people were killed in the fighting in Berlin and Munich.

prehistory

Empire and Social Democracy

The bourgeois March Revolution of 1848/49 failed primarily because of the problem of having to achieve national unification and democratization of Germany at the same time. After the state unity in the form of the Little German Solution under Prussian leadership had finally come about in 1871, large sections of the bourgeoisie came to terms with the authoritarian state and tended to increasingly nationalist ideas.

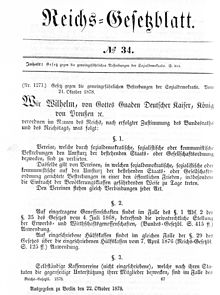

The newly founded German Empire was a constitutional monarchy . The Reichstag had universal, equal and secret male suffrage, but its influence on Reich politics was limited. Laws could only come into force with the consent of the Federal Council , which could dissolve it at any time and call new elections. The only other important authority of the Reichstag was to approve the state budget. However, within the framework of the so-called septnate, he was only allowed to vote on its largest post, the military budget, for a total period of seven years. The imperial government was responsible not to him, but to the emperor alone.

Social Democrats , whose parties merged to form the SPD in 1875, were also represented in the Reichstag from the start . As the only political party in the German Empire , it openly advocated a republican form of government. Otto von Bismarck therefore had them prosecuted on the basis of the socialist laws from 1878 until his dismissal in 1890 . Nevertheless, the Social Democrats were able to increase their share of the vote in almost every election. Since the Reichstag election in 1912 , in which they received 28 percent of the vote, they made up the strongest parliamentary group with 110 members.

In the 43 years from the founding of the Reich to the First World War, the SPD not only gained in importance, but also changed its character. In the revisionism dispute that had been going on since 1898, the so-called revisionists wanted to delete the goal of revolution from the party program. Instead, they advocated social reforms based on the existing economic order. Against this, the Marxist- oriented majority of the party prevailed once again. But the continuing revolutionary rhetoric only barely covered the fact that the SPD had become practically reformist since the repeal of the socialist laws in 1890. The Social Democrats, long defamed as “enemies of the Reich” and “ journeymen without a fatherland ”, saw themselves as German patriots . At the beginning of the First World War it became obvious that the SPD had become an integral - albeit opposition - part of the German Empire.

Approval of the SPD to the war credits

Around 1900, German social democracy was considered the strongest force in the international labor movement . At the pan-European congresses of the Second Socialist International , the SPD had always approved resolutions that provided for joint action by the socialists in the event that war broke out. Like other socialist parties in Europe , it organized large anti-war demonstrations in 1914 during the July crisis that followed the assassination attempt in Sarajevo . In a speech in Frankfurt am Main, Rosa Luxemburg , the spokeswoman for the left-wing party, called on the entire SPD to refuse war and obedience. She was therefore sentenced to several years in prison in 1915. The Reich government planned to arrest the party leaders immediately after the fighting began. Friedrich Ebert , one of the two SPD chairmen since 1913, traveled to Zurich with Otto Braun to keep the party funds safe from access by the state.

When, however, on August 1, 1914, the German declaration of war on Tsarist Russia , which was regarded as a refuge for reaction , the majority of the SPD party newspapers were infected by the general enthusiasm for the war . Their reporting was harshly criticized by the party leadership, but in the first days of August the editors believed they were following the line of SPD chairman August Bebel, who died in 1913 . In 1904 he said in the Reichstag that the SPD would take part in the armed defense of Germany in the event of a foreign war of aggression. In 1907 he affirmed at the Essen party congress that he himself would also “take the gun on his back” if it were to go against Russia, the “enemy of all culture and of all the oppressed”.

In view of the war-ready mood among the population, who believed in an attack by the Entente powers, many SPD members feared that consistent pacifism would alienate themselves from their voters. In addition, Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg threatened to ban parties in the event of war. On the other hand, the Chancellor used the anti-Tsarist attitude of the SPD skillfully to gain their approval for the war.

The party leadership and the Reichstag parliamentary group were divided in their stance on the war: with Friedrich Ebert, 96 deputies approved of the war credits required by the Reich government . 14 parliamentarians, headed by the second chairman Hugo Haase , spoke out against it, but nevertheless voted in favor of the faction's discipline. The entire SPD parliamentary group approved the war loans on August 4th. Two days earlier, the free trade unions had already decided to waive strikes and wages for wartime. With the trade union and party resolutions, the full mobilization of the German army became possible. Haase justified the decision he had rejected in the Reichstag with the words: We will not abandon the fatherland in the hour of danger! . At the end of his speech from the throne, the emperor welcomed the so-called truce of German domestic politics with the now famous sentence: I don't know any parties anymore, I only know Germans!

Even Karl Liebknecht , who later became a symbolic figure of resolute opponents of the war, leaned beginning of the party expediency: he stayed away from the vote in order not to have to vote against their own faction. A few days later, however, he joined the Internationale Gruppe , which Rosa Luxemburg had founded on August 5, 1914 with six other left parties and which adhered to the pre-war decisions of the SPD. From this emerged on January 1, 1916 the nationwide Spartacus League . On December 2, 1914, Liebknecht, initially as the only member of the Reichstag, voted against further war credits. This open violation of the parliamentary group's discipline was considered a taboo break and isolated it even among those SPD members around Haase who campaigned within the parliamentary group for a refusal of the loans. Liebknecht was drafted into the military in 1915 at the instigation of the party leadership as the only SPD parliamentary group member. Because of his attempts to organize the war opponents, he was expelled from the SPD and sentenced in June 1916 to four years in prison for high treason . After her temporary release, Rosa Luxemburg was also imprisoned until the end of the war.

Split of the SPD

The longer the war lasted and the more victims it claimed, the fewer SPD members were willing to maintain the "Burgfrieden" of 1914: all the less because since 1916 it was no longer the emperor and the imperial government that determined the guidelines of German policy, but the - meanwhile third - OHL under Generals Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff . They actually ruled as military dictators , with Ludendorff making the main decisions. They pursued expansionist and offensive war aims and also subordinated civil life entirely to the needs of warfare and war economy. For the workforce, this meant, among other things, a twelve-hour day with minimal wages and insufficient supplies.

After the outbreak of the Russian February Revolution in 1917 , the first organized strikes also took place in Germany . In March and April 1917, around 300,000 armaments workers took part. Since the USA's entry into the war on April 6th made a further deterioration of the situation likely, Kaiser Wilhelm II tried to appease the strikers with his Easter message of April 7th: He promised general, equal elections for Prussia after the end of the war , where until then the three-class voting system applied.

After the opponents of the war had been expelled from the SPD, so-called revisionists such as Eduard Bernstein and centrists such as Karl Kautsky reacted to the growing dissatisfaction in the working class, as well as the Spartacists . At a conference from April 6th to 8th, 1917 in Gotha they founded the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD) under Hugo Haase. It demanded the immediate end of the war and the further democratization of Germany, but had no uniform social policy program. The Spartakusbund, which had previously rejected a split, now formed the left wing of the USPD. In order to differentiate itself from the USPD, the SPD called itself from then on until 1919 Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany (MSPD).

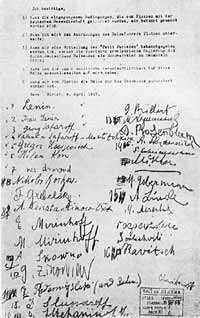

Effects of the October Revolution

In the course of the Russian February Revolution , Tsar Nicholas II had to abdicate on March 15, 1917. The power took over a government under Prince Georgi Lwow , which was composed of constitutional democrats and Mensheviks . Although this continued the war on the side of the Entente Powers, the OHL and the German Reich leadership saw the new situation as a chance for victory in the East. To heighten anti-war sentiment in Russia, they smuggled Lenin , the leader of the Russian Bolsheviks , who advocated an immediate end to the fighting, from his exile in Switzerland to St. Petersburg . In April he and a group of other Bolsheviks traveled in a sealed railway car that had been declared exterritorial via Germany and Sweden to revolutionary Russia.

In the October Revolution , Lenin's cadre party , which was also supported by Germany with considerable funds, prevailed against the moderate socialists and bourgeoisie and gained power in Russia. The new Bolshevik government began peace negotiations with the German Reich in Brest-Litovsk in December 1917. Nevertheless, Lenin's success increased the fear of a revolution based on the Russian model among the German bourgeoisie.

The SPD leadership also wanted to prevent a comparable development in Germany. This determined their behavior during the November Revolution. Board member Otto Braun clarified the position of his party in January 1918 in the party organ Vorwärts in the leading article The Bolsheviks and Us :

- Socialism cannot be erected on bayonets and machine guns. If it is to endure in the long term, it must be implemented democratically. A prerequisite for this is, of course, that the economic and social conditions are ripe for the socialization of society. If that were the case in Russia, the Bolsheviks would undoubtedly be able to rely on a majority of the people. Since this is not the case, they have established a saber rule that has not been more brutal and ruthless under the shameful regime of the Tsar. (...) That is why we must draw a thick, visible dividing line between the Bolsheviks and ourselves.

In the same month the so-called January strikes broke out , in which over a million workers took part across the empire. This movement was organized by the Revolutionary Obleuten , chaired by Richard Müller, of the USPD, who had successfully organized mass strikes against the war as early as 1916 and 1917 and were later to play an important role. The Berlin strike leadership in January 1918 called itself the “workers' council” based on the Russian “soviets” and was the godfather for the later council movement. In order to weaken their influence, Ebert joined the Berlin strike leadership and achieved an early strike.

Peace of victory or peace of understanding?

Since the USA entered the war in 1917, the situation on the Western Front has become increasingly precarious for the Reich. Therefore - and to take the wind out of the sails of the USPD - the MSPD , the Catholic Center Party and the Liberal Progressive People's Party formed the Intergroup Committee . They passed a peace resolution in the Reichstag in the summer of 1917 , which called for a mutually beneficial peace without annexations and contributions .

The OHL ignored the resolution, however, and forced a so-called "victory peace" in the peace negotiations with Russia. Under military pressure from Germany, the new Soviet government approved the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty negotiated by Leon Trotsky in March 1918 . This treaty imposed much tougher peace conditions on Russia than later the Versailles Treaty on the German Empire. A little later, this turned out to be a heavy mortgage. Because through its actions Germany exposed itself to the accusation of putting power over law. Logically, the Western powers used the treaty to strengthen the resistance of their own soldiers, since they could now point out what a German victory would mean for the defeated side.

In addition Brest-Litovsk introduced a de facto rejection of the 14-point program is that US President Woodrow Wilson had announced on January 8, 1918th In it he proclaimed the “ right of peoples to self-determination ” and envisaged a peace “without victors and defeated”. Hindenburg and Ludendorff ignored the offer because after the victory over Russia they believed that they could also force the remaining war opponents to a “victory peace” with far-reaching annexations. In the spring, many German politicians also indulged themselves in this illusion far into the democratic camp. Since the OHL was now able to deploy some of the troops that had become free in the east on the western front, most Germans believed that a victorious end of the war was now within reach in the west as well.

The German spring offensive in the west began in March, but soon came to a standstill after initial successes. On June 24th, Richard von Kühlmann , the State Secretary for Foreign Affairs, who had been the German negotiator in Brest-Litovsk that spring , spoke out in favor of a mutual agreement. According to this, the national territories of Germany and its allies were to remain untouched and these in turn were to renounce annexations in the west. Although a military victory was no longer possible after the failure of the last offensive, Ludendorff and Hindenburg also rejected Kühlmann's advance. Ludendorff even accused the State Secretary of State of jeopardizing the "victorious end of the war" and thus laid the foundation for the later stab in the back legend , according to which the army had failed due to a lack of support at home. Kühlmann received neither the support of the civil government nor the majority of the Reichstag, and had to resign on July 8 in favor of Paul von Hintzes , an admiral. With this, the OHL had once again gained the upper hand in German politics, but gambled away the last possibility of a mutual agreement.

Military defeat and constitutional reform

In the summer of 1918 it became clear that the German soldiers newly relocated to the Western Front could not outweigh the reinforcements Great Britain and France had received from the newly arrived US troops. Just a few days after Kühlmann's resignation, on July 18, 1918, the war finally turned around: In a counterattack in the second Battle of the Marne , the Allies won the initiative, which they did not lose again until the end of the war. At the end of July the last German reserves were used up and Germany's military defeat sealed. This became apparent to all military when the Allies broke through in the Battle of Amiens on August 8, the so-called " Black Day of the German Army ". In mid-September the Balkan front also collapsed . On September 29th, Bulgaria , which was allied with the Central Powers , surrendered . Even Austria-Hungary was about to collapse, which drew an Allied attack on southern Germany in the realm of possibility.

On September 29, the OHL informed the Kaiser and Chancellor Georg von Hertling in Spa, Belgium, about the hopeless military situation. Ultimately, Ludendorff demanded that the Entente be asked for a ceasefire , as he could not guarantee to hold the front for more than 24 hours. He also recommended that a central demand of Wilson be met and that the Reich government be put on a parliamentary basis in order to achieve more favorable peace conditions. In doing so, he shifted responsibility for the impending surrender and its consequences to the democratic parties : they should now eat the soup that they brought us , he told officers on his staff on October 1st. In doing so, he again laid the seeds for the later stab in the back legend.

Despite the shock of Ludendorff's situation report, the majority parties, especially the SPD, were ready to take over government responsibility at the last minute. Since the monarchist Hertling rejected the parliamentarization, Wilhelm II appointed Prince Max von Baden , who was considered liberal, as the new Chancellor on October 3rd . Social Democrats also entered his cabinet, including Philipp Scheidemann as State Secretary with no portfolio. The next day the new government offered the Allies the armistice demanded by Ludendorff.

The German public only found out about it on October 5th. In the general shock of the now apparent defeat in the war, the constitutional changes went almost unnoticed. The Reichstag also formally resolved this on October 28th. From then on the Chancellor was dependent on the confidence of the Reichstag. The Reichstag received control over the military administration, but not over command matters. The German Reich had thus also formally become a parliamentary monarchy . From the point of view of the SPD leadership, the October reforms fulfilled all of their important constitutional goals. Ebert therefore regarded October 5th as the “birth of German democracy” and considered a revolution after the emperor's voluntary relinquishment of power to be superfluous.

The Consequences of the Armistice Request

In the three weeks that followed, US President Wilson responded to Germany's request for a ceasefire on October 4 with three diplomatic notes . As preconditions for negotiations, he called for Germany's withdrawal from all occupied territories, the cessation of the submarine war and - albeit in clauses - the emperor's abdication. Wilson wanted to make it impossible for the Reich to resume the war even after a possible failure of the negotiations and to make the democratic process in Germany irreversible.

After the third Wilson Note on October 23, Ludendorff declared the Allied terms unacceptable. He asked for the war to be resumed, which he had declared lost a month earlier. It was not until the Entente's request for an armistice, submitted at his request, that the entire military weakness of the Reich had been revealed and its government had almost completely deprived of any room for negotiation. The German troops had prepared themselves for the near end of the war and were urging to come home. Their readiness to fight could hardly be re-awakened, and desertions increased.

The Reich government therefore stayed on the path that Ludendorff himself had chosen. She replaced him on October 26th as 1st Quartermaster General by General Wilhelm Groener . Ludendorff fled to neutral Sweden with the wrong passport . The third Wilson Note had convinced many soldiers, but also a large part of the civilian population and the representatives of the majority parties in the Reichstag that the emperor had to abdicate in order to achieve peace. On October 28, Philipp Scheidemann wrote to Chancellor Max von Baden demanding that Wilhelm II renounce the throne. The Kaiser then left Berlin and went to the headquarters in Spa . On November 5, the Allies agreed to the commencement of armistice negotiations, subject to German reparations payments. The German Armistice Commission arrived on November 8 at the meeting place in the Compiègne forest .

It turned out to be a heavy burden for Germany's future that Wilson was only willing to negotiate with representatives of the new, parliamentary government, not with Hindenburg and Ludendorff himself, whom he mistrusted. The two main people responsible for Germany's predicament therefore did not have to assume any responsibility for liquidating the war. This made it possible for Ludendorff to spread the lie about the stab in the back of the democratic politicians in the rear of the army “undefeated in the field”.

course

Kiel sailors' uprising

While the war-weary troops and the population disaffected with the imperial government expected the war to end soon, the German naval command in Kiel under Admiral Franz von Hipper was planning to send the entire ocean-going fleet on October 30 for a night advance into Southern Bight . This would have led to a naval battle with the Royal Navy , which was about twice as strong and reinforced by American battleships , and claimed thousands of lives without changing the outcome of the war. Neither the Kaiser nor the Reich Chancellor were informed, but Ludendorff was, however, who had been calling for the war to be resumed since October 23. The naval order of October 24, 1918 and the preparations for departure first triggered a mutiny among the affected sailors and then a general revolution that eliminated the monarchy in the Reich in a few days. The mutinous sailors did not want to be senselessly sacrificed in the already lost war. They were also convinced that they were acting in the interests of the new government, which was seeking peace negotiations with the Entente. A simultaneous attack by the fleet would have completely ruined their credibility. The Allies already had doubts about the honesty of the German armistice offer. They worsened after the German submarine UB-123 sank the RMS Leinster ferry in the Irish Sea on October 10, killing 500 people.

The publicist Sebastian Haffner therefore did not see the actual mutineers in the sailors. Rather, he described the Admiralty's project as "a mutiny by the naval leadership against the government and its policies" . Michael Salewski saw it similarly : The "rebellion of the admirals" followed, "logically consistent", the "revolution of the sailors".

The sailors' uprising began on Schillig -Reede off Wilhelmshaven , where the German deep-sea fleet had anchored in anticipation of the planned sea battle. On the night of October 29-30, 1918, some of the ship's crews first refused to give orders . On three ships of the III. In the squadron, the sailors refused to raise anchor. On the battleships of the 1st Squadron SMS Thuringia and SMS Helgoland , parts of the crews went over to open mutiny and acts of sabotage. When, however, some torpedo boats aimed their guns at these ships on October 31, around 200 mutineers initially holed up below deck, but were then arrested without resistance.

Since the naval command was no longer sure of the crew's obedience, they dropped their battle plan and ordered the squadron back to Kiel. After a trouble-free exercise in the Heligoland Bay, squadron commander Vice Admiral Kraft had 47 sailors from SMS Markgraf , who were considered the main ringleaders, arrested and arrested in Kiel while sailing through the Kiel Canal.

The sailors and stokers tried to prevent another departure and to have their comrades released. About 250 of them met on the evening of November 1st in the Kiel trade union building. They sent delegations to the officers, but they were not heard. As a result, they increasingly sought contact with unions, the USPD and the SPD. These were well organized and had numerous followers in Kiel, as the city's population consisted to a large extent of workers because of the large shipyards.

After the police closed the union building for November 2nd, several thousand sailors and workers gathered in the afternoon on the large parade ground the following day. They had responded to a call from sailor Karl Artelt and shipyard worker Lothar Popp , both USPD members. Under the slogan of peace and bread, the crowd demanded the release of the mutineers, an end to the war and better food supplies. Finally, the participants moved to the detention center to free the arrested sailors.

In order to prevent the demonstrators from advancing further shortly before their destination, a lieutenant named Oskar Steinhäuser ordered his patrol to fire warning shots first and then aimed shots into the crowd. Seven people were killed and 29 seriously injured. There was also shooting from the demonstration. Steinhäuser and two other officers were seriously injured by blows with the buttocks and gunshots, but, contrary to what was later said, they were not killed. This brief skirmish is considered to be the beginning of the revolution.

After the outbreak of violence, both the demonstrators and the patrol initially withdrew. Nevertheless, the mass protest turned into a general uprising . The next day, November 4th, groups of insurgents roamed the city. There were demonstrations in the large barracks in the north of Kiel. Karl Artelt organized the first soldiers' council , which was soon followed by others. Soldiers and workers brought Kiel's public and military facilities under their control. The governor of the naval base, Wilhelm Souchon , was forced to negotiate and release the jailed sailors. When, contrary to his agreement with Artelt, troops came to suppress the movement, they were intercepted by the insurgents. They either turned back or joined the insurrection movement. Thus, on the evening of November 4th, Kiel was firmly in the hands of around 40,000 revolting sailors, soldiers and workers. These now also demanded the abdication of the Hohenzollerns and the free and equal right to vote for men and women.

That same evening, the SPD member of the Reichstag, Gustav Noske , arrived in Kiel. Governor Souchon had telegraphed a request for an SPD deputy to be sent to bring the uprising under control on behalf of the new Reich government and the party leadership. The soldiers' council consisting of SPD and USPD supporters immediately elected Noske as its chairman. A few days later he took over Souchon's post as governor, while Lothar Popp became chairman of the Supreme Soldiers' Council. In the following years, Noske succeeded in suppressing the influence of the councils in Kiel. However, he could not prevent the revolution from spreading to all of Germany.

Expansion to the whole empire

Since November 4th, delegations of the revolutionary sailors swarmed into all major German cities. In taking over civil and military power, they met almost no resistance; only in Lübeck and Hanover did two local commanders attempt to maintain military discipline by force of arms. On November 6th Wilhelmshaven was in the hands of a workers 'and soldiers' council , on November 7th all the larger coastal cities as well as Braunschweig , Frankfurt am Main , Hanover, Stuttgart and Munich . King Ludwig III was there on the same day . overthrown by Bavaria as the first German federal prince. After a large demonstration by soldiers and workers , he fled the city. Kurt Eisner from the USPD proclaimed a republic in Bavaria as the first country in the empire and was elected Prime Minister of Bavaria by the Munich Workers 'and Soldiers' Council. By November 25, the other German monarchs were also forced to abdicate, the last being Prince Günther Victor von Schwarzburg Rudolstadt .

The workers 'and soldiers' councils consisted for the most part of supporters of the SPD and USPD. Their thrust was democratic , pacifist and anti-militarist . In addition to the princes, they only disempowered the all-powerful military general commands . All civil authorities and officials of the empire - police, city administrations, courts - remained untouched. Confiscations of property or occupations of factories hardly took place either, since such measures were expected from a new Reich government. In order to create an executive that was committed to the revolution and the future government, the councils initially only claimed the overall supervision of the authorities, which had previously been in the hands of the general commands.

This gave the SPD a real power base at the local level. But while the councils believed that they were acting in the interests of the new order, the party leaders of the SPD saw in them disruptive elements for a peaceful change of power that they believed had already taken place. Like the bourgeois parties, they called for the quickest possible elections to a national assembly that would decide the final form of government. This soon brought them into opposition to a large part of the revolutionaries. The USPD in particular tried to take up their demands. She, too, was in favor of elections to a national assembly as late as possible, in order to be able to create facts before the meeting that met the expectations of a large part of the working class.

Reactions in Berlin

Ebert agreed with Max von Baden that a social revolution must be prevented and state order must be maintained under all circumstances. He wanted to win the bourgeois parties, which had already worked with the SPD in the Reichstag in 1917, as well as the old elites of the empire for the state restructuring and avoid a feared radicalization of the revolution based on the Russian model. Added to this was his fear that the already precarious supply situation could collapse if the administration were taken over by revolutionaries inexperienced in it. He believed that the SPD would inevitably gain parliamentary majorities in the future, which would enable it to implement its reform projects. For these reasons, he acted as closely as possible to the old forces.

In order to be able to show his followers a success, but at the same time to save the monarchy, Ebert demanded the resignation of the emperor since November 6th. On November 7th, according to Max von Baden's notes, he declared: If the Kaiser does not abdicate, then the social revolution is inevitable. But I don't want it, yes, I hate it like sin. But Wilhelm II, who was still at the headquarters of the Supreme Army Command in Spa, Belgium, played for time. After the Entente had promised armistice negotiations on November 6th, he hoped to be able to return to the Reich at the head of the soon-to-be-released troops from the front and to crush the revolution by force. Max von Baden wanted to travel to Spa to personally convince the emperor of the necessary abdication. But that didn't happen because the situation in Berlin quickly deteriorated.

November 9, 1918: End of the monarchy

→ see also the proclamation of the republic in Germany

On the evening of November 8th, the USPD called 26 meetings in Berlin at which a general strike and mass demonstrations were announced for the next day. Ebert had then once again ultimately called for the emperor's abdication and wanted to announce this step at the meetings as a success of the SPD. In order to counter possible unrest, Prince Max von Baden had the 4th Jägerregiment, considered particularly reliable, relocated from Naumburg an der Saale to Berlin that evening .

But even the soldiers of this regiment were unwilling to shoot at compatriots. When their officers handed them hand grenades on the early Saturday morning of November 9th , they sent a delegation to the editorial office of the Social Democratic Party organ Forward to request an explanation of the situation. There they met Otto Wels , a member of the SPD Reichstag . He was able to convince the soldiers to support the leadership of the SPD and its policies. Then he won other regiments to subordinate themselves to Ebert.

With that, the military control over the capital fell to the Social Democrats. But Ebert feared that it could quickly slip away from them again if the USPD and Spartacists were to pull the workers on their side in the announced demonstrations. Because in the morning hundreds of thousands of people marched into the center of Berlin in several demonstrations. On their posters and banners were slogans such as "Unity", "Law and Freedom" and "Brothers, don't shoot!"

Around the same time, the emperor learned the results of a questionnaire among 39 commanders: even the soldiers at the front were no longer willing to obey his orders. The evening before, a regiment of guards had also refused to obey for the first time . In telegrams from Berlin, the Chancellor urged him to abdicate immediately, so that the news of this could have a soothing effect. Nevertheless, he hesitated further and considered resigning only as German Kaiser, but not as King of Prussia .

After all, Max von Baden acted on his own in Berlin. Without waiting for the decision from Spa, he issued the following statement at noon that day:

- The emperor and king decided to renounce the throne. The Chancellor remains in office until the questions connected with the abdication of the Kaiser, the resignation of the Crown Prince of the German Empire and Prussia and the establishment of the regency have been settled.

When the declaration became known in Spa, Wilhelm II fled occupied Belgium into exile in the Netherlands , first to Amerongen , then to Doorn , where he lived until his death in 1941. Since he did not sign the deed of abdication in Amerongen until November 28, crossing the border was tantamount to deserting. That also cost him the sympathy of his military.

In order to remain in control of the situation, Ebert demanded the office of Reich Chancellor for himself at noon on November 9th and asked Max von Baden to take over the office of Reich Administrator. He then handed over the Chancellery to him, the State Secretaries remained in office. With this Ebert believed he had found a transitional arrangement until a regent was appointed.

The news of the emperor's resignation came too late to make an impression on the demonstrators. Nobody heeded the calls to return home or to the barracks published in the special editions of the Vorwärts . More and more demonstrators demanded the abolition of the monarchy. Karl Liebknecht, only recently released from prison, traveled to Berlin immediately and re-established the Spartakusbund the day before . Now he was planning the proclamation of the socialist republic.

During lunch in the Reichstag, the deputy SPD chairman Philipp Scheidemann found out about it. He did not want to let the Spartakists take the initiative and, on the spur of the moment, stepped onto a balcony of the Reichstag building. From there he in turn proclaimed the republic - against Ebert's declared will - in front of a demonstrating crowd. The exact wording of his proclamation is controversial. Scheidemann himself reproduced it two years later:

- The emperor has abdicated. He and his friends have disappeared, and the people have triumphed over all of them. Prince Max von Baden has handed over his Reich Chancellery to Member of Parliament Ebert. Our friend will form a workers' government to which all socialist parties will belong. The new government must not be disturbed in its work for peace and the care for work and bread. Workers and soldiers, be aware of the historical significance of this day: something unheard of has happened. Great and obvious work lies ahead of us. Everything for the people. Everything through the people. Nothing can happen that dishonors the labor movement. Be united, faithful, and conscientious. The old and rotten, the monarchy has collapsed. Long live the new. Long live the German Republic!

It was only hours later that Berlin newspapers published that Liebknecht had proclaimed the socialist republic in Berlin's Lustgarten - probably almost simultaneously - to which he once again swore a crowd gathered in the courtyard of the Berlin City Palace at around 4 p.m.

- Party comrades, I proclaim the free socialist republic of Germany, which should include all tribes. In which there will be no more servants, in whom every honest worker will find the honest wages of his work. The rule of capitalism, which has turned Europe into a mortuary, is broken.

Liebknecht's goals, which corresponded to the demands of the Spartakusbund of October 7th, had hardly been made public until then. This included, above all, the restructuring of the economy, the military and the judiciary, among others. a. the abolition of the death penalty . The main point of contention with the MSPD was the demand to socialize some economically important sectors of the economy before the election of a constituent national assembly. H. placed under the direct control of workers' representatives. The MSPD, on the other hand, wanted to leave Germany's future economic order to the Constituent Assembly (National Assembly).

In order to take the edge off the revolutionary mood and to meet the demands of the demonstrators for unity of the workers' parties, Ebert now offered the USPD entry into the government and agreed to accept Liebknecht as minister. This demanded control of the workers' councils over the soldiers and made his participation in government dependent on it. Because of the debates about it and because party chairman Hugo Haase was in Kiel, the USPD representatives could no longer agree on Ebert's offer that day.

Neither the premature announcement of the imperial renunciation of the throne by Max von Baden and his handover of the Chancellery to Ebert, nor the proclamation of the republic by Scheidemann were constitutionally protected. All of these were revolutionary acts by actors who did not want the revolution , but who nonetheless created permanent facts. That same evening, on the other hand, a deliberately revolutionary action took place, but in the end it turned out to be in vain.

Around 8 p.m., a group of 100 revolutionary stewards from large Berlin companies occupied the Reichstag and formed a revolutionary parliament. The stewards were largely the same people who had acted as strike leaders during the January strike. They mistrusted the SPD leadership and, in alliance with the USPD left and the Spartacus group, had been working towards a revolution for weeks. Surprised by the sailors' uprising, they initially set November 11 as the date for the coup. But after the group's military expert, Ernst Däumig , who had all the insurrection plans with him, was arrested on November 8, the alliance decided to act immediately. In order to wrest the initiative from Ebert, the revolutionary parliament decided to call elections for the next day: every Berlin company and regiment was to appoint workers' and soldiers' councils that Sunday, which would then elect a revolutionary government consisting of both workers' parties. This council of people's representatives was supposed to carry out the resolutions of the revolutionary parliament according to the will of the representatives and replace Ebert's function as Reich Chancellor.

November 10, 1918: SPD leadership against revolutionary representatives

The SPD leadership learned of the plans of the revolutionary stewards on Saturday evening. Since the elections to the council meeting and this itself could no longer be prevented, Ebert sent speakers to all the Berlin regiments and factories that night and the following morning. They should influence the elections in his favor and announce the USPD's planned participation in government.

These activities did not escape the stewards. When it was foreseeable that Ebert would also set the tone in the new government, they planned to propose to the council assembly not only to elect a government but also to set up an action committee. This should coordinate the activities of the workers 'and soldiers' councils. The stewards had already prepared a list of names for this election, on which the SPD was not represented. So they hoped to be able to set up a control over the government that would suit them.

In the assembly that met on the afternoon of November 10th in the Busch Circus , the majority were on the side of the SPD: almost all soldiers 'councils and a large part of the workers' representatives. They now repeated the demand for "unity of the working class" that had been made the day before by the revolutionaries and now used the slogan to implement Ebert's line. As planned, the USPD sent three of its representatives to the six-member “Council of People's Representatives”, which was now elected: its chairman Haase, the Reichstag delegate Wilhelm Dittmann and Emil Barth for the Revolutionary Obleute. The three SPD representatives were Ebert, Scheidemann and Otto Landsberg, a member of the Reichstag from Magdeburg .

The surprising proposal by the SPD leadership to also elect an action committee as a control body sparked heated debates. Ebert finally succeeded in ensuring that this 24-person Executive Council of the Workers 'and Soldiers' Councils in Greater Berlin was made up of SPD and USPD members on an equal footing. Richard Müller , the spokesman for the Revolutionary Obleute , became chairman of the Executive Council. The USPD mandates of the council were also occupied by the stewards. The Executive Council decided to convene a Reich Councilor Congress in Berlin for December .

Although Ebert had retained the decisive role of the SPD, he was dissatisfied with the results. He saw the council parliament and the executive council not as aids, but only as obstacles on the way to a state order that should be seamlessly linked to the empire. The entire SPD leadership viewed the councils as a danger, but not the old military and administrative elites. She greatly overestimated their loyalty to the new republic. Ebert was particularly bothered by the fact that he could no longer appear before them as Reich Chancellor, but only as chairman of a revolutionary government. Indeed, conservatives viewed him as a traitor, even though he had come to the fore of the revolution in order to slow it down.

During the eight-week dual rule of the councils and the imperial government, the latter was always dominant. The state secretaries and senior civil servants, who were formally subject to the supervision of the Council of People's Representatives, worked alone to Ebert, although Haase was formally equal chairman in the council. The decisive factor in the question of power was a phone call from Ebert on the evening of November 10th with General Wilhelm Groener , the new 1st Quartermaster General in Spa, Belgium. This assured Ebert the support of the army and received Ebert's promise to restore the military hierarchy and to proceed against the councils.

Behind the secret Ebert-Groener Pact was the concern of the SPD leadership that the revolution could lead to a Soviet republic based on the Russian model. The expectation of being able to win over the imperial officer corps for the republic was not to be fulfilled. At the same time, Ebert's behavior became increasingly incomprehensible to the revolutionary workers and soldiers and their representatives. The SPD leadership lost more and more confidence among its supporters without gaining sympathy among the opponents of the revolution.

In the turmoil of that day it was almost forgotten that the Ebert government had accepted the Entente's harsh conditions for a ceasefire that morning after another request from the OHL. On 11 November early in the morning, the Center Member Matthias Erzberger signed the Compiègne armistice on behalf of Berlin . This ceasefire came into force on the same day at 11 a.m. French time and 12 p.m. German time and was initially valid for 30 days. This ended the fighting of the First World War.

Stinnes Legien Agreement

As they did about the state, the revolutionaries had very different ideas about the future economic order . In both the SPD and the USPD, the demand was widespread that at least the war-important heavy industry should be subject to democratic control. The left wing of both parties and the Revolutionary Supervisors also wanted to establish direct democracy in the production area. The delegates elected there should also control political power. Preventing this council democracy was not only in the interests of the SPD, but also in that of the unions , which the councils threatened to make superfluous.

At the same time as the revolutionary events, the chairman of the General Commission of the German Trade Unions , Carl Legien , and other trade union leaders met from November 9th to 12th in Berlin with the representatives of large-scale industry under Hugo Stinnes and Carl Friedrich von Siemens . On November 15, they signed a joint venture agreement that benefited both sides: the union representatives promised to ensure orderly production flow, end wildcat strikes , reduce the influence of the councils and prevent the socialization of productive property. In return, the employers guaranteed the introduction of the eight-hour day and recognized the unions' claim to sole representation. Both sides formed a central working group with an equal central committee at the top. At the association level, arbitration committees, which were also represented equally, should mediate in future conflicts. It was also agreed to set up workers' committees in every company with more than 50 workers. Together with the company management, they should monitor compliance with collective agreements.

In doing so, the unions had achieved some of what they had been asking for years in vain. At the same time they had undermined all efforts to socialize the means of production and largely eliminated the councils.

Transitional government and council movement

The Reichstag has not been convened since November 9th. The Council of People's Representatives and the Executive Council had replaced the old government. But the previous administrative apparatus remained almost unchanged. Representatives of the SPD and USPD were only assigned to the officials who had been imperial until then. These also all retained their functions and continued their work largely unchanged.

On November 12th, the Council of People's Representatives published its democratic and social government program. He lifted the state of siege and censorship , abolished the rules of the servants and introduced universal suffrage from the age of 20, for the first time also for women. All political prisoners received amnesty . Regulations on freedom of association , assembly and freedom of the press were issued. On the basis of the working group agreement, the 8-hour day was prescribed and benefits from unemployment welfare, social and accident insurance were expanded.

At the pressure of the USPD representatives, the Council of People's Representatives set up a Socialization Commission on November 21 . You belonged u. a. Karl Kautsky , Rudolf Hilferding and Otto Hue . It should examine which industries are “suitable for socialization” and prepare for the nationalization of the coal and steel industry . This commission met until April 7, 1919 without any tangible result. “Self-governing bodies” were only set up in coal and potash mining and in the steel industry , from which today's works councils emerged . A socialist expropriation was not initiated.

The SPD leadership preferred to work with the old administration than with the new workers 'and soldiers' councils, as they did not trust them to provide the population with an orderly supply. This has led to constant conflicts with the Executive Board since mid-November. This changed his position continuously, depending on the interests of those he represented. Ebert then withdrew more and more authority from him with the aim of finally ending the “ruling around and in by the councils in Germany”. He and the SPD leadership overestimated not only the power of the council movement, but also that of the Spartakusbund. For example, the Spartacists never controlled the council movement, as conservatives and parts of the SPD believed.

The workers 'and soldiers' councils dissolved u. a. in Leipzig , Hamburg , Bremen , Chemnitz and Gotha the city administrations and put them under their control. In Braunschweig , Düsseldorf , Mülheim an der Ruhr and Zwickau , all officials loyal to the emperor were also arrested. “Red Guards” were formed in Hamburg and Bremen to protect the revolution. In the Leunawerke near Merseburg , councils deposed the corporate management. Often the new councils were determined spontaneously and arbitrarily and had no leadership experience. Some were corrupt and selfish. The newly appointed councilors faced a large majority of moderate councils, who came to terms with the old administration and worked with it to ensure that calm was quickly restored in factories and cities. They took over the distribution of food, police violence as well as the accommodation and catering for the soldiers who were gradually returning home. Administration and councils were dependent on each other: some had knowledge and experience, others political influence.

Most of the time, SPD members were elected to the councils, which viewed their activities as a temporary solution. For them, as for the majority of the rest of the population, the introduction of a soviet republic or even a Bolshevik council dictatorship in Germany was never up for debate in 1918/19. Rather, a majority of the councils supported the parliamentary system and the election to a constituent national assembly, since the decades-long practice of Reichstag elections and the parliamentary work of the SPD had proven their worth in their eyes.

Many wanted to support the new government and expected it to abolish militarism and the government . War weariness and hardship gave the majority of the people hope for a peaceful solution and led to some of them overestimating the stability of what had been achieved.

First counter-revolutionary violence and Imperial Councils Congress

As decided by the Executive Council, the workers 'and soldiers' councils sent delegates from all over the Reich to Berlin, who were to meet on December 16 in the Circus Busch for the First General Congress of Workers 'and Soldiers' Councils . Because they feared a Bolshevization of Germany when it met, parts of the Berlin garrison undertook an armed action at the beginning of December, which some referred to as an attempted coup, while others like Richard Müller referred to it as a mere "antics". In any case, it made a significant contribution to increasing the distrust between the SPD and the extreme left.

On the morning of December 6th, at the instigation of Hermann Wolff-Metternich , who later had to give up his command as the main actor in the attempted coup and had to flee Germany, a troop of the Kaiser Franz infantry regiment, after the original plan to carry out the arrest by members of the People's Navy Division let failed, the Prussian House of Representatives , in which the Executive Council met, and declared it arrested. The soldiers believed they were acting in the interests of the Council of People's Deputies. Because when his member Emil Barth of the USPD, who was in the House of Representatives, pointed out to the soldiers that the government had not issued an arrest warrant against the Executive Council, they withdrew after a brief debate. At the same time, other soldiers of the "Franzer Regiment" gathered in front of the Reich Chancellery under the leadership of a sergeant named Kurt Spiro. They protested against the “mismanagement” of the Executive Council, called for elections to the National Assembly in December and finally proclaimed Friedrich Ebert President. The latter replied evasively because he shied away from breaking with the Executive Council, so that this group also gave up in the end without having achieved anything. Whether this attempted coup was a spontaneous action or was initiated by parts of the government apparatus has never been investigated and is therefore still controversial today.

The tragic consequences of this "great spook", as Philipp Scheidemann called the action, only became apparent on the afternoon of December 6th: Upon the news of the coup attempt, several Spartakist demonstrations were formed, led by Police President Emil Eichhorn, a USPD member , had been approved. The city commandant, Otto Wels from the SPD, had not heard of this approval. Therefore, he had the demonstration route on the corner of Chausseestrasse and Invalidenstrasse cordoned off by a section of guard fusiliers armed with a machine gun. For reasons that are still unexplained, they opened fire on the demonstrators and hit a tram during the evening rush hour. 16 people died.

This incident deeply poisoned the atmosphere between the Spartacists and their opponents in the MSPD and the bourgeois parties. Both sides blamed each other for the escalation of violence. The Spartakist “ Rote Fahne ” wrote on December 7th: “The bloody crime must be punished, the conspiracy of the Wels, Ebert, Scheidemann must be crushed with an iron fist, the revolution saved.” On the other side, among the bourgeoisie, Liebknecht was again in to an extent of a frightening figure that was out of proportion to its realpolitical possibilities. Only 800 to 1000 people gathered for a Spartacist protest demonstration on December 7th, but as the demonstrators carried two armored cars and several machine guns, the fears of their opponents were further incited.

On December 10, Ebert and 25,000 citizens welcomed ten divisions returning from the front at Pariser Platz . In his speech he called out to them: “No enemy has ever conquered you! Germany's unity is now in your hands! ”With which he unintentionally promoted the stab-in- the-back legend , according to which the war defeat was not due to the strength of the Western powers, but to the weakness of Germany as a result of the revolution. Nevertheless, this event was a great success for the majority social democracy, which presented itself as a guarantor of German unity and an overcoming of the current turmoil.

The Reichsrätekongress, which began its work on December 16 in the Prussian House of Representatives, consisted in its majority of supporters of the SPD. Not even Karl Liebknecht had succeeded in gaining a mandate there. His Spartakusbund was not allowed to have any influence. On December 19, the councils voted 344 to 98 against the creation of a council system as the basis for a new constitution. Rather, they supported the government's decision to hold elections as soon as possible to a constituent national assembly that would decide on the final form of government.

The only point of contention between Ebert and Congress was over control of the military. Among other things, the congress demanded that the “ Central Council of the German Socialist Republic ” elected by it have a say in the supreme command of the armed forces, the free election of officers and the disciplinary power for the soldiers' councils. But this ran counter to the secret agreement between Ebert and Groener. Both did everything possible to undo the decision. The Supreme Army Command, which had meanwhile moved to Kassel , began to set up their loyally devoted Freikorps , which they intended to deploy against the supposedly impending Bolshevik danger. These troops were monarchist-minded officers and men who could not find a way back into civilian life and who rejected the republic.

Failure to take control of the troops through the War Department itself and instead maintain its partnership with the OHL ultimately made the revolutionary government dependent on the protection of those who were deeply hostile to the revolution. Historians such as Heinrich August Winkler and Joachim Käppner rate this as the Ebert government's greatest mistake.

Christmas crisis

After November 9, the government ordered the newly formed People's Navy Division from Kiel to Berlin to protect it . She was considered to be absolutely loyal and in fact refused to participate in the attempted coup on December 6th. The sailors even removed their commander because they saw him involved in the affair. But after various art treasures had been stolen from the city palace in which the troops were stationed, the council of people's representatives demanded that they be dissolved and withdrawn from the palace. Otto Wels , city commandant of Berlin since November 9, put the sailors under pressure by withholding their pay .

The dispute escalated on December 23rd during the Christmas battles . The sailors mutinied and occupied the Reich Chancellery. You clipping off the phone lines, presented the Council of People's Representatives under house arrest and took Wels in stables as a hostage and abused him. Contrary to what would have been expected from Spartacist revolutionaries, they did not use the situation to eliminate the Ebert government, but only continued to insist on their wages. Ebert, who was in contact with the Supreme Army Command in Kassel via a secret telephone line, gave the order on the morning of December 24th to attack the castle with troops loyal to the government. This attack failed. 56 government soldiers, eleven sailors and some civilians lost their lives. After renewed negotiations, the sailors cleared the castle and stables and released Wels. In return, he lost his office as city commander, the People's Navy Division received its pay and remained as a military unit. The affair showed the defenselessness of the government, which had no reliable and powerful troops of its own. The crisis thus strengthened the alliance between Ebert and Groener, which, according to historian Ulrich Kluge, only came about as a result of the Christmas battles. The defeated government troops were either disbanded or integrated into the newly formed Freikorps. To make up for the loss of face, they temporarily occupied the editorial offices of the Rote Fahne . But military power in Berlin was now again in the hands of the People's Naval Division, and once again it did not take advantage of it.

This shows on the one hand that the sailors were not Spartacists, on the other hand that the revolution had no leadership. Even if Liebknecht had been the revolutionary leader in Lenin's sense, whom legend later made of him, the sailors and the councilors would hardly have accepted him as such. The only consequence of the Christmas crisis, which the Spartacists referred to as “Ebert's Blood Christmas”, was that the revolutionaries called for a demonstration for Christmas Day and the USPD left the government on December 29 in protest. But this was only right for the SPD chairman, since he had only included the independents in government under the pressure of the revolutionary events. Within a few days, the Ebert government's military defeat turned into a political victory.

Founding of the KPD and January uprising

After the Christmas riots, the Spartacus leaders no longer believed that they could bring about the socialist revolution with the SPD and USPD. In order to absorb the dissatisfaction of their supporters and many workers with the course of the revolution to date, they convened a Reich Congress at the turn of the year to found their own party. Rosa Luxemburg presented the Spartacus program she had written on December 10, 1918 on December 31. It was adopted as the party program with a few changes and stated that the new party would never take over government without a clear majority will. On January 1, 1919, the Spartakists who had traveled there founded the KPD together with other left-wing socialist groups from all over the Reich . Rosa Luxemburg once again called for their participation in the planned parliamentary elections, but was overruled. The majority continued to hope to be able to gain power through continued agitation in the factories and the pressure of the “street”. However, after negotiations with the Spartacists, the “revolutionary stewards” decided to remain in the USPD.

The left's decisive defeat occurred in the first days of the new year 1919. As in November, a second wave of revolution arose almost spontaneously, but this time it was violently suppressed. It was triggered when the government dismissed USPD member Emil Eichhorn as police chief of Berlin on January 4th . Eichhorn had refused to take action against demonstrating workers during the Christmas crisis. The USPD, revolutionary stewards and the KPD leaders Karl Liebknecht and Wilhelm Pieck took his dismissal as an opportunity to call for a protest action for the next day.

What was planned as a demonstration developed into a mass march that the organizers themselves had not expected. As on November 9, 1918, on January 5, 1919, a Sunday, hundreds of thousands poured into the center of Berlin, including many armed men. In the afternoon they occupied the Berlin train stations and the Berlin newspaper district with the editorial buildings for the bourgeois press and the Vorwärts . In the days before, some of the newspapers concerned had not only called for the formation of further voluntary corps, but also for the murder of the Spartakists. The protesters were essentially the same as they were two months earlier. They now demanded the redemption of what they had then hoped for. The demands came from the workers themselves and were supported by the various groups on the left of the SPD. The Spartacists were by no means leading. The so-called Spartacus uprising that followed was only partly initiated by KPD supporters. These even remained in the minority among the rebels.

The initiators of the demonstrations gathered in the police headquarters elected a 53-member "Provisional Revolutionary Committee", which, however, did not know what to do with its power and did not know how to give the uprising a clear direction. Liebknecht, one of the three chairmen alongside Georg Ledebour and Paul Scholze , called for the government to be overthrown and joined the majority opinion in the committee that propagated armed struggle. Like the majority of KPD leaders, Rosa Luxemburg considered an uprising at this point in time to be a catastrophe and expressly spoke out against it.

On January 4th, Ebert had appointed Gustav Noske as the people's representative for the army and navy. On January 6th, Noske took over the command of these troops with the words: “All right, someone has to become the bloodhound. I do not shy away from the responsibility. ”On the same Monday the Revolutionary Committee called for another mass demonstration. More people responded to this call. They again carried posters saying, "Brothers, don't shoot!" And paused at a meeting place. Some of the revolutionary officials began to arm themselves and to call for the overthrow of the Ebert government. But the efforts of the KPD activists to get the troops on their side were largely unsuccessful. Rather, it became apparent that even units like the People's Navy Division were not prepared to actively support the armed uprising. She declared herself neutral. The majority of the other regiments stationed in Berlin continued to support the government.

While other troops were advancing on Berlin on his behalf, Ebert accepted an offer from the USPD to mediate between him and the Revolutionary Committee. After the troop movements and an SPD leaflet with the title “The hour of reckoning is approaching”, the committee broke off further negotiations on January 8th. Ebert then ordered the troops stationed in Berlin to take action against the occupiers. From January 9th, they violently suppressed their improvised attempted insurrection. On January 12th, the anti-republic free corps that had been set up since the beginning of December also marched into the city. After they had brutally evacuated several buildings and shot the occupiers with the law, the others quickly surrendered. Some of them were shot as well. 156 people fell victim to this practice in Berlin.

Assassination of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg

The alleged masterminds of the January uprising had to go into hiding, but refused to leave Berlin despite urgent requests from their comrades. On the evening of January 15, 1919, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were arrested in an apartment in Berlin-Wilmersdorf and handed over to Captain Waldemar Pabst , the leader of the Guard Cavalry Rifle Division , in the Hotel Eden . He had them interrogated, during which they were ill-treated, and planned their murder with his officers. Around midnight, both of them were taken out of the hotel one after the other in a car. At the hotel exit, the soldier Otto Wilhelm Runge previously knocked both of them almost unconscious. On the way, the naval officer Horst von Pflugk-Harttung shot Karl Liebknecht and Lieutenant Hermann Souchon Rosa Luxemburg. Kurt Vogel , also an officer in the rifle division, had Liebknecht's body handed over to a police station and that of Rosa Luxemburg thrown into the Landwehr Canal, where it was not found until May 31, 1919. Pabst presented the acts in a press release as lynching of unknown perpetrators.

Paul Jorns , a military judge chosen by the rifle division itself, acquitted Harttung in June 1919 and sentenced Runge to two years, Vogel to two and a half years. Pabst and Souchon, however, were neither prosecuted nor charged. Noske had the appeal proceedings against Runge and Vogel suspended. After 1933 the National Socialists compensated Runge for imprisonment and prosecution and transferred the guard cavalry to the SA . Souchon's involvement in the murder was not known until 1968 and proved in 1992. The nephew of Wilhelm Souchon, the governor of Kiel during the sailors' uprising, always denied the crime and was never punished. After the Second World War , Pabst stated that Noske had approved his murder order by telephone. In his diary, which was discovered later, he noted in 1969 that the SPD leadership had covered him and thwarted his prosecution.

The Freikorps became a permanent power factor after the suppression of the January uprising. What weighed more heavily in the long term was that the murders of January 15, as well as the lack of clarification and persecution, exacerbated the rift between the SPD on the one hand and the USPD and KPD on the other. During the Weimar Republic, the SPD and KPD were never able to agree on joint action, especially since the KPD became dependent on the Comintern and its ideological guidelines after the murder of its founders . The split in the left that began in 1919 contributed significantly to the later rise of National Socialism .

Further uprisings and general strikes

In the first months of 1919 further uprisings, general strikes and attempts to found a Soviet republic followed in several areas of Germany.

At the end of January, Noske decided to take violent action against the Bremen Soviet Republic . Despite an offer to negotiate from the other side, he ordered the voluntary corps units to invade the city. About 400 people were killed in the fighting that followed. As a reaction to this, there were mass strikes in Berlin , Saxony , Upper Silesia , the Rhineland and the Ruhr area . Some of them were aimed at driving the revolution further, for example with the socialization movement in the Ruhr area . A general strike began in Berlin on March 4th, which the workers' councils had called for the councils to be recognized and permanently established, as well as a democratic military reform and socialization. Around a million employees took part and brought economic life and traffic to an almost complete standstill. When the military intervened, it was decided to extend the strike to the utilities. The strike front, which had been largely closed until then, broke up, and street fighting broke out again, against the will of the strike leadership. At the request of the Prussian government, which had meanwhile declared a state of siege, Noske deployed troops against the strikers and the People's Navy Division. They killed at least 1,200 people by March 16, including many unarmed, bystanders and 29 members of the People's Navy Division. The latter were arbitrarily executed, as Noske had ordered every martial law to shoot, which is to be met with a gun.

Civil war-like situations also arose in Hamburg and Saxe-Gotha . The Munich Soviet Republic lasted until May 2, 1919, when Prussian, Württemberg and Freikorps troops ended it with similar excesses of violence as in Berlin and Bremen.

According to current research, the establishment of a Bolshevik council system in Germany has never been in the realm of probability since the beginning of the revolution, especially since the democratically minded SPD and USPD supporters, who made up the majority of the councils, rejected a dictatorship anyway. Nevertheless, the Ebert government felt threatened by an attempted coup by the radical left and entered into an alliance with the Supreme Army Command and the Freikorps. Their brutal approach during the various uprisings has alienated many left-wing democrats from the SPD. They viewed the behavior of Ebert, Noske and other SPD leaders during the revolution as a betrayal of their own supporters.

National Assembly and new Imperial Constitution

On January 19, 1919, the elections to the constituent national assembly took place, the first in Germany, to which the right to vote for women also applied. It turned out that the transition from monarchy to parliamentary republic was supported by an overwhelming majority of Germans. The SPD was 37.4 percent of the vote, by far the strongest party in the elections and put 165 of the 423 deputies. The USPD only got 7.6 percent and 22 MPs. After the Kapp-Lüttwitz Putsch in 1920, it temporarily gained in importance again, but dissolved in 1922. The second strongest force, with 19.7 percent of the vote, was the Center Party, which entered the National Assembly with 91 members. The liberal DDP won 18.5 percent and 75 seats. The National Liberal DVP came with 4.4 percent to 19, and the conservative - nationalist DNVP 10.3 percent to 44 mandates. Contrary to Rosa Luxemburg's advice, the KPD did not take part in the elections.

In order to escape the revolutionary turmoil in Berlin, the National Assembly met on February 6 in Weimar . It set up a provisional constitutional order and on February 11, elected Friedrich Ebert as Reich President . On February 13, he appointed a government under Philipp Scheidemann as Reich Minister-President. It was supported by the so-called Weimar coalition made up of the SPD, the center and the DDP. Germany thus had a legitimate, post-revolutionary government again.

The new Weimar constitution , which made the German Reich into a democratic republic, was passed with the votes of the SPD, Zentrum and DDP and signed by the Reich President on August 11, 1919. It stood in the liberal and democratic tradition of the 19th century and took over ideas from the Paulskirche constitution of 1849. However, because of the majority in the National Assembly, central demands of the November revolutionaries remained unfulfilled: the socialization of the coal and steel industry and the democratization of the officers' corps, which had already been done by the Kieler The workers 'and soldiers' council had demanded and the Reichsrätekongress had initiated, as did the expropriation of big banks , big industry and aristocratic large estates . Employment and pension rights of imperial officials and soldiers were expressly protected.

On the one hand, the Weimar Constitution contained more possibilities for direct democracy than the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany. B. Referendum and referendum ; On the other hand, Article 48 of the Emergency Ordinance granted the Reich President extensive powers to rule against the majority of the Reichstag and, if necessary, to deploy the military at home. This article proved to be a crucial means of destroying democracy in 1932-33.

reception

The November Revolution is one of the most important events in recent German history , but it is hardly anchored in German historical memory. The failure of the Weimar Republic that emerged from it and the subsequent period of National Socialism blocked the view of the events at the turn of the year 1918/19 for a long time. To this day, their interpretation is determined more by legends than by facts.

Both the radical right and the radical left - under opposite signs - nurtured the idea that there had been a communist uprising at the time with the aim of transforming Germany into a Soviet republic based on the Soviet model. For a long time the parties in the democratic center, especially the SPD, had little interest in a fair assessment of the events that made Germany a republic. Because on closer inspection, they turn out to be a revolution supported by social democrats, which was stopped by the social democratic party leaders. The fact that the Weimar Republic turned out to be a weak democracy and went under again 14 years later also has to do with this and other birth defects during the November Revolution.

Of great importance was the fact that the imperial government and the Supreme Army Command shirked their responsibility at an early stage and placed the majority parties in the Reichstag on the majority parties in the Reichstag to deal with the defeat they were responsible for in the First World War. A quote from the autobiography of Ludendorff's successor, Groener, shows the calculation behind this:

- I could only appreciate it if the army and command remained as unencumbered as possible during these unfortunate armistice negotiations, from which nothing good could be expected.

This is how the so-called stab in the back legend arose , according to which the revolutionaries stabbed the army "undefeated in the field" in the back and only then turned the almost certain victory into a defeat. Erich Ludendorff, who wanted to cover up his own serious military mistakes, made a significant contribution to the spread of this falsification of history . The legend fell on fertile ground in nationalist and ethnic circles . There the revolutionaries and even politicians like Ebert - who had absolutely no intention of the revolution and who had done everything to channel and contain it - were soon defamed as “ November criminals”. The radical right did not shy away from political murders, for example of Matthias Erzberger and Walter Rathenau . It was a deliberate symbolism that the Hitler coup of 1923 was also carried out on November 9th.

From the time it was born, the republic was tainted with defeat in war. A large part of the bourgeoisie and the old elites from large-scale industry, large-scale agriculture, the military, the judiciary and administration never accepted the new form of government, but instead saw the democratic republic as an entity that should be eliminated at the first opportunity. The Prussian Ministry of the Interior had to issue a special decree on March 27, 1920, which stipulated that the symbols of the monarchy - including the images of the emperors - should be removed from public space. On the left, however, the behavior of the SPD leadership during the revolution drove many of its former supporters to the communists. According to Kurt Sontheimer , the slowed November revolution meant that the Weimar Republic remained a “democracy without democrats”.

With a few exceptions, historical research has only found a balanced assessment of the November Revolution since the 1960s.

Judgments from contemporary witnesses

Contemporaries judged the November Revolution very differently depending on their political convictions. This is made clear by statements made partly during or immediately after the events of November 1918, partly from retrospect.

The Protestant theologian and philosopher Ernst Troeltsch registered, rather calmly and with a certain relief , how the majority of Berlin's citizens perceived November 10th:

- On Sunday morning after the anxious night, the picture from the morning papers became clear: the emperor in Holland, the revolution victorious in most of the centers, the federal princes about to abdicate. No man dead for emperor and empire! The continuation of the obligations secured and no storming of the banks! (…) Trams and subways went as usual, the guarantee that everything was in order for the immediate needs of life. On all faces was written: The salaries will continue to be paid.

The liberal publicist Theodor Wolff was extremely optimistic about the success of the revolution in an article that appeared in the Berliner Tageblatt on November 10th :