Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (born February 4, 1871 in Heidelberg , † February 28, 1925 in Berlin ) was a German social democrat and politician . From 1913 to 1919 he was chairman of the Social Democratic Party of Germany and from 1919 to his death in 1925 he was the first Reich President of the Weimar Republic .

After the death of August Bebel Ebert was next to Hugo Haase Chairman of the face of the impending war fractious SPD selected. During the war he strongly advocated the policy of "defense of the fatherland" and domestic political stagnation ( civil peace policy ) against those Social Democrats who rejected this policy. In the November Revolution of 1918, his party and the USPD, which had split off from them, took over government. The Weimar National Assemblyelected Ebert on February 11, 1919 as the first Reich President. In the years 1919 to 1923 Ebert had several revolts by revolutionary socialists suppressed by force of arms. He also took decisive action against coup attempts from the right in 1920 and 1923. Otherwise he appeared as a politician of the balance of interests. His early death at the age of 54 and the subsequent election of the monarchist-minded Paul von Hindenburg to the head of state represent a turning point in the Weimar Republic.

Shortly after his death in 1925, the Friedrich Ebert Foundation , which was close to the SPD and named after him, was founded.

Life

youth

Friedrich Ebert was born the seventh of nine children, three of whom died in infancy. His father Karl was a master tailor , but like his mother Katharina (née Hinkel) came from a small-scale family. His mother was a Protestant, the father a practicing Catholic. Ebert was baptized a Catholic on March 19, 1871, but later left the Church. The exact time is unknown, but Ebert was already listed as a “dissident” when he was elected to the Reichstag in 1912. The father temporarily employed journeymen and apprentices. The family's wealth was modest.

Ebert attended elementary school without attracting any particular attention. Ebert's desire to become a priest, mentioned by some biographers, would not have been an unusual path to social advancement. There is no evidence of this. Between 1885 and 1888 he learned the craft of saddler . At the trade school, Ebert made such an impression on one of the teachers that he even advised him to study. However, he never took the journeyman's examination. Then Ebert went on a journey between 1888 and 1891 . He mainly traveled to southern and western Germany. Stations included Karlsruhe , Munich , Mannheim , Kassel , Hanover , Braunschweig , Elberfeld (now part of Wuppertal ), Remscheid , Quakenbrück and Bremen .

On the way, he was committed to bringing together craftsmen in trade unions and professional associations. He was temporarily unemployed . In Mannheim he got to know the socialist and trade union movement through a stepbrother of his father who lived there and joined the Socialist Workers' Party of Germany (SAP) around 1889 . Also in 1889 he joined the Saddlery Association. It was during this time that Ebert first got an insight into Marxist writings and works by Ferdinand Lassalle .

After joining the party and union, he worked as an agitator and organizer. In 1889 he became secretary of the saddler's association in Hanover. Ebert founded them in cities in which he found no branches during his wandering. In Kassel he organized a successful labor dispute. He was not only observed by the state in the context of the Socialist Law until its repeal in 1890, but was blacklisted by employers as an unwelcome agitator.

Bremen years

In May 1891 Ebert came to Bremen , where he lived for 14 years. Here, too, he was committed to the party and the union. He became chairman of the local saddlery association. He also headed the illegal local free trade union cartel . After the death of his father, Ebert returned to Heidelberg for a short time in 1892. Since he had to give up his job because of this, he tried to exist as a self-employed craftsman and casual worker after returning to Bremen.

In March 1893 Ebert got a permanent position as an editor at the " Bremer Bürger-Zeitung ", the newspaper of the Bremen SPD. As early as the following year he left the editorial office and took over the inn "Zur gute Hilfe" as a leaseholder on Brautstrasse in the Neustadt district . He did not appreciate this activity and later did not mention it in official résumés. His political opponents tried to capitalize on it:

“As long as, for example, the historical memory of Frederick the Great has not died, Friedrich Ebert can only arouse limited astonishment. The hero of Sanssouci behaves to the former Bremen pub owner like the sun to the moon; only when the rays of the sun go out, the moon can shine. "

Politically, the economy was a meeting place for trade unionists and social democrats. In terms of material matters, the Ebert company allowed him to marry Louise Rump (1873–1955) and start a family in May 1894 . The couple had four sons and a daughter Amalie (1900–1931). The sons Georg (1896–1917) and Heinrich (1897–1917) died in the First World War. The eldest son Friedrich (1894–1979) was also politically active (initially for the SPD, later as an SED functionary) and became Lord Mayor of East Berlin after the Second World War . Karl (1899–1975) was a member of the state parliament in Baden-Württemberg for the SPD from 1946 to 1964 . Heinrich Jaenecke (1928–2014), son of his daughter Amalie, worked as a journalist, publicist and historian.

Because of his numerous speeches for the party and trade unions, the police authorities rated him as the most zealous agitator in Bremen as early as 1891. His speeches were based on thorough research, but were also characterized by sharp-tongued and irony. However, he also occasionally lost his temper in discussions and critics accused him of being arrogant.

In 1892 Ebert presented a study on the "situation of workers in the Bremen bakery trade". A year later he became a member of the party's press commission for the Bremer Bürgerzeitung. In March 1894 he became party chairman in Bremen and held this position until 1895. In the election campaigns for the Bremen citizenship , Ebert had been a leader for the SPD since 1896. In the same year he was for the first time a delegate at a party rally of the SPD. In 1897 Ebert was responsible for agitation in the rural outskirts of Bremen. In this position he ran for the first time for the Reichstag in the safe central constituency of Vechta in 1898 , but remained unsuccessful. From 1902 Ebert was again a member of the Bremen party executive.

Over time, social policy became the real focus of Ebert's political activity. His inn became a point of contact for those seeking advice. This made him familiar with the needs of the working class, which preoccupied him intensively. In order to solve the specific problems, Ebert considered state aid to be essential. This resulted in his political classification: For him, fighting current social grievances was more important than the hope of the collapse of capitalism or the theoretical debates about the economy and society. For Ebert, winning elections was the central means of moving the ruling classes to change. Participation in parliaments with the aim of achieving improvements for the working population made it necessary to find compromises with other political parties, but also meant a certain recognition of the existing system.

At Ebert, it was not political but trade union work that dominated. He remained chairman of the saddler's association in Bremen and was a leader in the local union cartel . The voluntary social and legal advisory activity performed by Ebert in his restaurant became very extensive, and the idea of professionalising this activity by employing a workers' secretary arose in the Bremen trade unions . Resolutions on this had been in place since 1897, but initially failed due to the resistance of the individual trade unions to transfer a large part of their membership fees for this purpose. It was not until 1900 that Ebert was hired as a workers' secretary. This enabled him to give up the little-loved inn. Ebert familiarized himself with his new role on a long study trip that took him to Nuremberg and Frankfurt am Main , among others . Following the Nuremberg model, he himself then wrote a regulation applicable to the Bremen Secretariat, which, among other things, provided for advice not only to union members, but to all those seeking advice.

When it turned out that Ebert could not cope with the tasks alone, Hermann Müller (Lichtenberg) was hired as an additional secretary in 1900 . In addition to providing advice, the secretaries also carried out statistical studies on the social situation in Bremen. In doing so, Müller and Ebert filled a gap, because the city of Bremen's statistical office did not publish any comparable data at the time. It is worth mentioning the result of a statistical survey of the living conditions of the Bremen workers from 1902 with data on the work, wage and housing conditions in the Hanseatic city. As a result, the city authorities began to publish relevant statistics.

Group leader in the citizenry

Despite the eight-class suffrage, which was very obstructive for the Social Democrats , Ebert succeeded in being elected to the Bremen parliament by a by-election in December 1899, to which he belonged until 1905. Although he was new to the city parliament, he was elected chairman by the faction of his party formed for the first time. In parliament he focused on social and economic policy, but also took care of constitutional problems. He belonged to several commissions and deputations . Due to the special structure of the Bremen constitution, the parliamentary group was only able to pass a few motions. This was one reason to sharply attack liberal domination as “class rule”. The course of the parliamentary group under Ebert's leadership was marked on the one hand by constructive cooperation, on the other hand by fundamental criticism and the demand for constitutional reforms.

At first Ebert saw no problem in reconciling this parliamentarian strategy with the Marxist goals of the Erfurt program . For a long time he represented a strictly centrist course on the line of the party executive around August Bebel . That is, he stuck to the idea of the class struggle , the transfer of private property into common property, and focused on the collapse of the capitalist system. At the same time, practical work to improve living conditions was a central goal for him. As an advocate of strict party unity, he was an opponent of both the left-wing critics of the “Junge” and the reformist Georg von Vollmar and later the revisionists around Eduard Bernstein .

For Ebert, the organizational strength of the trade unions and the party became the decisive factor during this time. It was clear to him that only maximum strength and internal unity would enable the socialist movement to wrest concessions from its political opponents and employers. Since he believed that the internal party dispute would damage party unity, Ebert had been rejecting these theoretical disputes since 1899. When the revisionism controversy flared up again at the Dresden party congress in 1903, Ebert, as a delegate, agreed to reject Bernstein's theses, but expressed himself more differently afterwards. He spoke of a necessary merging of the revolutionary and evolutionary paths and called this the “diagonal of forces.” If this was understood as revisionism, the majority of the party would consist of revisionists. Again he asked to end the theoretical discussions in favor of the practical work. Sharp criticism of the behavior of the party leadership around Bebel at the party congress was exercised by a resolution by Ebert's party members in Bremen. Overall, a gradual move away from older positions can be observed. Over the years, Ebert has at least partially distanced himself from the Erfurt program. In 1905, criticism from parts of the Bremen SPD earned him his positive assessment of the non-partisan cooperation in the educational institution “Goethebund”. The fact that Ebert had distanced himself from the majority of the Bremen party after the departure of men like Franz Diederich and Hermann Müller is shown by the party's decision to end cooperation with the liberals in this league.

Advancement within the party

Party organizer

Gradually Ebert became known nationwide within the SPD. The 1904 Reich Party Congress, which met in Bremen, contributed to this. As president, Ebert headed the party congress and was up to the task. In Bremen, on the other hand, he and the more reform-minded wing he represented lost influence, while left-wing forces around Heinrich Schulz and Alfred Henke pushed forward. Although the contrast was not as clear as in later years, to which Ebert had contributed through a balancing attitude, he was not satisfied with his position in Bremen.

He therefore applied for the newly created position of party secretary in the party executive. Ebert was elected against Hermann Müller (Franconia) at the 1905 party congress. A year later, Müller received a comparable position. Ebert belonged to the executive committee of the party. This position meant a clear financial improvement. The reason for the creation of the new position was that the seven paid members of the party executive needed someone to take over the bureaucratic routine work for which there was no time apart from political work in the party or in the Reichstag. In contrast to later legends, however, Ebert did not set up a bureaucratic apparatus on the party executive with the help of which he could later rise to party chairman. Rather, he initially took care of gaining a correct overview of the membership numbers and promoting the organization of the party at local and regional level. However, the conception was not just Ebert's business, but was driven by a group of board members, in particular Wilhelm Dittmann .

The practical implementation was mainly in Ebert's hands until 1909/10. The relationship with the subdivisions became Ebert's main task. He traveled to the party branches in the country, monitored the implementation of the party congress resolutions and helped with organizational and political issues, resolved internal conflicts and presented the wishes and criticisms of the branches in the party executive committee. It was precisely this that made Ebert known among the many full-time and part-time functionaries, who came to appreciate him for his tireless efforts.

Within the board of directors, he gradually gained in stature. It was of great importance that August Bebel broke down his initial reservations about Ebert and trusted him. In addition to the purely bureaucratic work, Ebert was therefore increasingly given politically significant tasks. So he became the liaison of the SPD to the general commission of the trade unions . Having attended trade union meetings, he was as familiar with internal operations in the General Commission as he was in the party leadership. Ebert was also involved in the joint youth work of the party and the trade unions.

Although he made contacts abroad in this context, international relations and foreign policy issues remained marginal issues for Ebert. Apart from these policy areas and education policy, Ebert was soon more familiar with the central political issues and of course the organization than most of the other board members.

Member of the Reichstag and party chairman

After Paul Singer's death in 1911, the SPD party congress in Jena in September 1911 elected Hugo Haase as co-chairman of the SPD alongside long-time chairman August Bebel in a vote against Ebert. According to other information, Ebert withdrew his candidacy shortly before the ballot and recommended Haase's election himself, but still got 102 votes in the election.

In 1912 Ebert ran in the Elberfeld - Barmen constituency of the Reichstag . What is remarkable is that the party there was more leftist. This suggests that Ebert was not viewed as a reformist or revisionist, but as a man of compromise and guardian of party unity. Ebert did not run in a constituency that was safe for the party. Despite considerable efforts, he did not succeed in winning the mandate in the first ballot, but only in the runoff ballot. In the following years he kept in close contact with his constituency and stood up for him in the Reichstag.

The SPD parliamentary group had become the strongest political force in the Reichstag in 1912 with 110 members. Although Ebert was new, he was elected to the seven-member parliamentary committee. In the plenary session, Ebert concentrated on social policy and the question of pay. All in all, he rarely spoke in parliament and never on issues of public interest.

After August Bebel's death in 1913, Ebert was the favorite for his successor because of his work in the party and parliamentary group, his close ties to the trade unions and the branches of the party. With 433 of 473 votes, he was elected chairman alongside Haase on September 20, 1913 at the SPD party congress in Jena. He saw his main task in holding the diverging wings together. The small concrete steps to improve living conditions were still more important to him than the ideological disputes.

First World War

Consent to the war credits

Ebert was surprised by the July crisis on vacation in 1914 , which followed the assassination attempt in Sarajevo . He traveled to Zurich with Otto Braun to set up a foreign line in the event of an SPD ban and to bring the party coffers to safety. Ebert did not stay in Switzerland and was back in Berlin on August 4th. He had thus missed the previous day's resolution in the Reichstag parliamentary group to approve war credits. Then he made it clear that he was behind the majority of the parliamentary group and not behind the minority around Haase. He later reported on the following session of the Reichstag: “The war with Russia and France had become a fact. England lay in wait to strike on some pretext as well. Italy does not participate, and Austria is Austria. The danger is great, our people were also under this impression. "

In doing so, he expressed the majority mood among the party base, which in Germany, as almost everywhere in Europe, had turned from massive rejection of the war to enthusiastic approval within a few days. Almost all workers' parties in Europe believed the national propaganda , regarded the behavior of their own governments as "defense" and that of the others as "attack" and put aside domestic political contradictions in favor of "national unity". This broke the 2nd International . Characteristic for this was the sentence with which the SPD parliamentary group justified its approval in the Reichstag on August 4th: "We will not abandon the fatherland in the hour of danger."

Ebert and with him other supporters of war credits also linked this decision with the hope of being able to obtain concrete concessions in economic, social and political terms as the price for approval. The conservatives feared that the political balance in the light of Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg proclaimed truce could move to their disadvantage.

End of party unity

Despite his stance on war credits, Ebert initially tried to maintain the threatened party unity and made concessions to the critics of the war course. When in December 1914, after the Battle of the Marne and the failure of the German war planning against France, another approval of war credits was due, Ebert succeeded once more in swearing the parliamentary group members to his line. Only Karl Liebknecht refused to give his consent.

As a result, internal conflicts broke out openly. The right wing of the party around Eduard David , Wolfgang Heine and the union representatives demanded Liebknecht's exclusion from the parliamentary group. Ebert and Haase tried to prevent this. The collaboration between Ebert and Haase ended after Haase, together with Eduard Bernstein and Karl Kautsky, sharply criticized the emerging annexationist war aims of the Reich government in the Leipziger Volkszeitung on June 19, 1915 and called on the SPD to openly resist. At Ebert's instigation, the SPD party committee condemned Haase's behavior on June 30, 1915 as “inconsistent with the duties of a chairman”. Philipp Scheidemann , Ebert's internal party rival, noted in his diary: "Ebert treated him [Haase] directly brutally."

Before the Reichstag session on December 9, 1915, the opposition within the SPD parliamentary group had grown to around 45 votes. Haase and Georg Ledebour demanded that the minority should also have a say in the plenary, especially since they had no other opportunity to represent their position publicly due to military censorship. The faction majority around Ebert rejected this, however, and nominated Otto Landsberg as the second speaker who called on the German people to "self-defense".

Haase then resigned as chairman of the parliamentary group and on December 21, 1915 made a special declaration by the war opponents in the Reichstag for the first time. Ebert criticized this sharply, but initially spoke out against the exclusion of the minority. On January 11, 1916, Ebert was elected group chairman alongside Scheidemann with a narrow majority. Not only the left, but also some of the right refused to consent. He still considered the break with factional unity to be avoidable. Above all, he hoped to keep the pacifist group around Bernstein and Kurt Eisner , who had belonged to the revisionists before the war, in the party.

In March 1916, Haase spoke surprisingly in the plenary against accepting the note budget after Scheidemann, representing the SPD majority, had advocated it. Then Ebert and others accused Haase of “breach of discipline” and “disloyalty” and demanded that the Haase group be excluded from the parliamentary group. On March 16, 1916, the opponents of the war were expelled from the joint faction. They were constituted as a Social Democratic Working Group (SAG) . The majority began to use their better connections to the apparatus of the party and to the trade unions outside the parliamentary group in order to enforce their position. In a stroke of a hand, the party executive replaced the largely left-wing editorial staff of the party newspaper Vorwärts with its own people. From then on, the split in the party could no longer be stopped. On March 25, the party executive forced Hugo Haase to resign as party chairman. In January 1917, the SAG members and their supporters in the party organization were also expelled from the party. After another winter of starvation, the first spontaneous mass strikes and the United States' entry into the war , they founded the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD) in April 1917 .

Strive for domestic reforms

Ebert's hope for a turnaround in domestic politics was not fulfilled. Certain concessions in favor of the workers could only be achieved with the auxiliary service law. The lack of reforms led in 1917 to the formation of a new majority in parliament from (M) SPD, center , progress party and parts of the National Liberals . These parties worked together on the July 1917 peace resolution . This spoke out in favor of a "peace without annexations". The text largely corresponded to the demands of the Social Democrats. When the government made no move to reform the three-tier suffrage , Ebert threatened the main committee with refusing the next war loans. Ebert and the parliamentary group were the driving forces behind the formation of the intergroup committee , which should try to push through the reform demands. This initially led to Bethmann-Hollweg falling and the Supreme Army Command being given greater weight.

Also in 1917 there were the first large demonstrations and strikes against the war. For the MSPD, these became a serious problem because they strengthened the USPD. Ebert defended the USPD, against which the new Chancellor Georg Michaelis stepped up in the summer of 1917. He openly threatened: "But if the Reich leadership should really embark on such a policy (...), we will consider it our highest task to fight it most ruthlessly with the use of all our strength and all our conscience of duty." the government. In the subsequent formation of a government under Georg von Hertling , Ebert was heavily involved. However, even this new government did not fulfill hopes for peace and reform. Instead, she was responsible for the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty , which in the east, under pressure from the OHL, laid down considerable territorial restructuring of the formerly Russian areas. This made Ebert and the parliamentary group go back into opposition to the government.

In the country, however, the protests intensified and in January 1918 led to the large munitions workers' strike in Berlin. The MSPD threatened to break away from the mass base in the face of agitation by the USPD and the Spartakusbund . Although Ebert refused the strike, he took part in the strike leadership. After the war he was called a traitor to the workers because of this, while the right defamed him as a traitor. In truth, he took part because, on the one hand, he believed the demands were legitimate, and, on the other hand, wanted to end the strike quickly because he believed that it would not contribute to achieving peace.

Parliamentarization of the empire

At the parliamentary level, there were new efforts from September 1918 to parliamentarise the Reich and to end the war as quickly as possible. On September 12, Ebert made it clear that the SPD would not support the Hertling government because of its subordination to the OHL. Basically, the SPD was ready to join the government now. Among other things, it made it a condition that no all-party coalition be formed, but sought a government made up of the parties represented in the intergroup committee. This government should commit itself to a speedy peace agreement and domestic political reforms. Ebert connected this with the hope of being able to avert an impending revolution in this way. Ebert swore the leading majority Social Democrats to take responsibility:

- “If we don't want an understanding with the bourgeois parties and the government, then we have to let things go, then we resort to revolutionary tactics, stand on our own feet and leave the fate of the party to the revolution. Anyone who has seen things in Russia cannot, in the interests of the proletariat, wish that such a development should occur in us. On the contrary, we have to step in the breach, we have to see if we can get enough leverage to get our demand through and, if it is possible, to combine it with saving the country, then it is our damned duty and debt to do so to do."

Ultimately, Ebert and Scheidemann prevailed with this course. This new government was formed under Prince Max von Baden . This was able to succeed not least because the OHL itself pushed for parliamentarization. The reason for this was that the defeat of the German armed forces had become inevitable since the Black Day of the German Army on August 8, 1918 at the latest . Erich Ludendorff in particular wanted to shift responsibility for this to the majority parties in parliament.

The Reich was formally parliamentarized on October 28, 1918 with the amendment of the constitution. Philipp Scheidemann and Gustav Bauer had already joined the new government beforehand . In Prussia, however, the electoral reforms did not make progress and negotiations on a ceasefire were also delayed. Ebert had changed from a republican to a monarchist of reason during the war because he believed that an abrupt end of the monarchy could not be supported by the majority of the citizens. Basically, Ebert wanted to keep the monarch even after the form of government was converted into a parliamentary system, and he strived for a parliamentary monarchy . On November 6th, against the background of the beginning revolution, he pushed for Emperor Wilhelm II and the Crown Prince to renounce the throne in favor of another member of the Hohenzollern family.

When the OHL under Wilhelm Groener refused to participate in such a plan, the SPD made its ultimate demands on November 7th. In this way, the party tried to position itself at the head of the popular movement that demanded the abdication of the emperor and crown prince. In talks with Max von Baden, among others, Ebert made it clear that the SPD was raising its claim to political leadership precisely to prevent a revolutionary overthrow movement. In this context, Ebert Max von Baden said, “If the Kaiser does not abdicate, then the social revolution is inevitable. But I don't want them, yes I hate them like the plague. "

November Revolution

Formation of the Council of People's Representatives

After the Kiel sailors' uprising , there was disarmament, city hall occupations, mass demonstrations and fraternization of workers and deserted soldiers throughout the empire. The November revolution spread to all German cities in a few days. Gustav Noske traveled to Kiel on Ebert's order to contain the revolution there.

On November 9, 1918, a political general strike began in Berlin, to which the SPD had also called. Thereupon Prince Max von Baden arbitrarily transferred the office of Chancellor to Ebert, who had risen to a politician of national importance during the war years. At the same time, the prince announced the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II without his consent and without support in the constitution. Scheidemann publicly proclaimed the republic from a window of the Reichstag and announced that Ebert was its Chancellor. This happened against Ebert's will, who wanted to maintain continuity with the empire until a constituent assembly would decide between monarchy or republic. The emperor fled to the Netherlands .

Ebert placed himself at the head of the revolution in order to steer it into parliamentary channels and to prevent a development analogous to the Russian October Revolution . He appointed other Social Democrats to the cabinet and at the same time tried to involve the USPD in the government in order to increase its legitimacy base vis-à-vis the workers 'and soldiers' councils that were being formed everywhere . Since the councils in Kiel, Berlin and elsewhere were pushing for an agreement between the two social democratic parties, the USPD leadership around Haase was forced to comply with Ebert's requests after a controversial debate. On November 10, the SPD and USPD agreed on the formation of an equal council of people's representatives . The bourgeois ministers should initially remain in office, but be controlled by representatives of the socialist parties. On the same evening, this decision was approved by the general assembly of the Berlin workers 'and soldiers' councils gathered in the Busch Circus .

Ebert Groener Alliance

With Ebert, the MSPD had the strongest position of power in this constellation. He chaired the meetings of the Council of People's Representatives and those of the entire government, thus determining the course of debates in the government, reserved domestic and military policy and was recognized by the bureaucracy as head of government. Haase, who was formally equal, took a back seat.

The most important power base of Ebert and the MSPD was their support from the revolting soldiers. When the Council of People's Representatives was formed, another power factor - the OHL (and thus the entire military) - had not yet been involved. On the evening of November 10, Wilhelm Groener offered to support the army on behalf of OHL Ebert . The Ebert-Groener alliance and the non-dissolution of the OHL were also supported by the USPD members of the Council of People's Representatives with a view to the upcoming tasks of returning the troops to the Reich and demobilization . But behind this was Ebert's intention, in the event of further revolutionary movements, to get hold of a means of power that could be used domestically. In addition, a power vacuum should be prevented that would have enabled radical groups to usurp power. In addition, given the unclear borders with Poland, the military still seemed necessary. The alliance gave the OHL the opportunity to expand the military's temporarily limited political leeway and to work on establishing a conservative counter-resistance against the government. Even if Ebert had succeeded in supporting the new order with the alliance for the time being, his hope of subordinating the military to the civilian government in the long term failed.

For quick elections to the National Assembly

Ebert saw the government he led as a temporary arrangement that had to act as the bankruptcy administrator of the old man and hold power in trust until a new government based on the democratic elections of the entire people was installed. The aim of the Ebert government was, in addition to the enormous tasks that were initially imminent, such as demobilizing the army and ensuring the food supply, to eliminate the Prussian-German authoritarian state, to establish a classic western-style democracy and to maintain the political alliance between workers and bourgeoisie, which Ebert on the one hand and in particular the leading center politician Matthias Erzberger, on the other hand, had brought about a year earlier with the intergroup committee. The MSPD wanted to introduce socialism in a democratic way. A revolution like the one in Russia, which had led to the Bolshevik dictatorship and civil war , she firmly opposed. In order to counteract such a development in Germany, Ebert wanted to end the revolution and initiate elections for a national assembly as soon as possible.

So Ebert found himself in opposition to revolutionary forces who insisted on the revolution continuing. Within the Council of People's Representatives, the USPD representatives advocated using the revolutionary phase to implement a number of far-reaching demands of social democracy such as socialization and to postpone the calling of the National Assembly. At the Reichsrätekongress , however, Ebert found a large majority for his policy: with 400 votes to 50, the delegates of the workers 'and soldiers' councils voted for the election of a national assembly at the earliest possible time.

The coalition between the SPD and the USPD was effectively broken. The external reason was the Christmas fights when, on the morning of December 24, 1918, regular troops of the Berlin General Command, at Ebert's request, shot at the New Marstall and the Berlin City Palace with artillery. The mutinous People's Navy Division was stationed there. After a dispute over its dissolution and the outstanding payment of its wages, it occupied the Reich Chancellery and took Berlin city commander Otto Wels hostage and mistreated it. The conquest failed, among other things, because of the intervention of the security forces, which was under the authority of Berlin Police President Emil Eichhorn (USPD). Ebert negotiated a compromise that freed Wels and had the People's Navy Division withdrawn, but brought in the outstanding pay and a guarantee of existence.

Opinions differ on Ebert's role in this crisis. The historian Ulrich Kluge suspects that Ebert deliberately did without the help of loyal armed forces from the Potsdam Workers 'and Soldiers' Council in order to justify his cooperation with the OHL and the deployment of regular troops through ostentatious helplessness. Ebert's biographer Walter Mühlhausen, on the other hand, cites Noske's memories from 1920, according to which the government's calls for help were only "80 men." According to Groener's memoirs, it was extremely difficult for Ebert to authorize him to use military force against the mutinous sailors. The historian Hagen Schulze believes it is possible that Ebert intentionally escalated the conflict over the People's Navy Division in order to push the USPD out of government. In fact, on December 28th, they sharply criticized Ebert's “blank check” for the troops as well as the artillery bombardment of the castle and resigned from the joint interim government on December 29th in protest against these measures. At the turn of the year, the Spartakusbund convened a Reich Congress at which various left groups united to form the KPD . A majority there refused to participate in the elections to the National Assembly scheduled for January 19.

After Ebert's remaining government ousted the Berlin Police President Eichhorn, workers close to the Revolutionary Obleuten occupied the Berlin newspaper district on January 5, 1919 . Appeals for murder on the leaders of the left had previously been published from there. After failed negotiations and to forestall the expansion of a general strike , Ebert gave the military the order on January 8 to put down the Spartacus uprising . Ebert wanted to stem the revolution in an alliance with the Supreme Army Command. On January 10th, Noske's free corps moved into the city. This practically ended the November Revolution, which had helped Ebert to become chancellor, and a preliminary decision on the nature of the Weimar constitution had been made.

On January 15, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were murdered by officers of the largest free corps, the Guard Cavalry Rifle Division . Their first general staff officer, Waldemar Pabst , said that he had previously telephoned Reichswehr Minister Noske. In the months that followed, the other attempts to establish a council system in major German cities were also militarily suppressed.

Reich Presidency

Understanding of office and political scope

On January 19, 1919, the election for the German National Assembly took place. The SPD was the strongest party with 37.90%, but remained dependent on coalitions with the Center Party and the Liberals until the end of the Weimar Republic . The National Assembly , which will meet in Weimar on February 6, elected Ebert as President of the Weimar Republic on February 11, 1919. The reasons why Ebert sought this office and not that of the Reich Minister President are unclear, because there are no personal reports about it. In his speech after the election he defined the office of the Reich President as the guardian of national unity, as the protector of law and internal and external security.

“I want to and will act as the representative of the entire German people, not as the foreman of a single party. But I also confess that I am a son of the working class, raised in the world of ideas of socialism, and that I am never inclined to deny my origins or my convictions. "

Ebert did not only want to concentrate on the representative function of the office, but also saw the task of the presidents in advising and intervening in disputes. This required familiarity with what was happening in the country. In order to meet this requirement, Ebert asked for his own machine. He met with strong resistance from Reich Minister President Philipp Scheidemann and also from the SPD parliamentary group in the National Assembly. They feared that such a subsidiary government could emerge. Only the bourgeois government of Constantin Fehrenbach granted the Reich President adequate staffing. After a few predecessors, Otto Meißner took over the management.

In order to get the most accurate information possible, Ebert had the Reich Ministry of Economics draw up comprehensive economic reports as early as 1919. He was also informed about the situation of the workers and tried to mediate in conflict cases between the social partners or other opponents in the social and economic area. Before making important decisions, he often received the ministers responsible. However, Ebert's skills were ultimately limited in this regard. His wish to compensate for the social cuts of 1923 on the other hand to burden the property owners more financially, was not followed by the Reich Ministry of Finance; Rather, it operated the opposite policy. He had good information and contacts in foreign policy. But in this area too, Ebert was often informed too late about important decisions, such as the Rapallo Treaty , to be able to change anything. He did not even learn details of German-Soviet relations, such as the secret arming of Germany with the help of the USSR. Outwardly, despite all the criticism expressed internally, Ebert supported the foreign policy of the German governments.

the Versailles Treaty

Ebert played a not insignificant role during the crisis surrounding the acceptance of the Versailles Treaty . At first he had kept a low profile on the matter, but it was clear to him that there was no realistic alternative. Philipp Scheidemann and part of the government did not want to support this and announced their resignation. Ebert chaired the last attempts at agreement in the cabinet, in the intergroup deliberations and in negotiations between the Reich and the Länder. However, he did not succeed in preventing Scheidemann from resigning. An appeal to the SPD parliamentary group also failed. He successfully urged Gustav Bauer to form a new government. After the signing, Ebert spoke out in favor of unconditional loyalty to the contract, but also strove for a revision of the Versailles Treaty.

Public image

Ebert's presidency was continuously accompanied by malicious polemics from German national or communist publicists and politicians. The historian and Ebert biographer Walter Mühlhausen speaks of a "dirt campaign that accompanied Ebert until his untimely death".

The campaign began on July 16, 1919, when Ebert and Reichswehr Minister Noske visited a children's rest home run by the Hamburger Konsumgenossenschaft Produktion in Haffkrug and had their photos taken while they were bathing in the Baltic Sea. They wore unfavorably fitting swimming trunks instead of the swimsuits that had been common for men until then. The picture by photographer Wilhelm Steffen was first published on August 9, 1919 in the conservative German daily newspaper . The second use only caused a stir when the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung (BIZ) opened the photo on August 21, 1919, the day on which Ebert was sworn in as President of the Reich on the new Reich constitution . For this purpose it had been circumcised and now only showed the Reich President, the Reichswehr Minister and Josef Riege crouching in front of them in a joking Neptune pose . The journalists of the left-liberal Ullstein Verlag intended to find a tongue-in-cheek and entertaining lead story on the occasion of the swearing-in, which showed a celebrity as a private person on summer vacation - a popular magazine subject.

Nonetheless, the picture caused quite a stir, as it portrayed the new Reich President as undignified and irresponsible. Ebert, who did not have a well-rehearsed department for public relations in the Reich President's Office , initially only had the party newspaper Vorwärts spread that the photo was "unjustifiably ... brought to the public". At least the editor-in-chief of the BIZ, Kurt Korff , and the Ullstein director Georg Bernhard apologized to Ebert, but the picture was in the world.

In the period that followed, it was reprinted, quoted and caricatured again and again, until the swimming trunks finally became an icon of anti-republic polemics. The joke paper Kladderadatsch , which got caught up in the nationalistic waters, published a parody of the imperial hymn Heil dir im Wreath : “Heil dir am Badestrand / Ruler in Vaterland / Heil, Ebert, dir! / You have the Badebüx, / otherwise you have nothing more / than adornment of your body. / Heil, Ebert, dir! ”The German daily published a postcard that contrasted the bathing suit photo with pictures of Kaiser Wilhelm II and Hindenburg in sumptuous uniforms; the headline was "then and now". Thus the image finally became a weapon for the disavowal and delegitimization of the new republic and its representatives.

In September 1919, Ebert filed a criminal complaint against those responsible for the postcard under press law - it was the first of around 200 libel and defamation trials that he led during his tenure - but only achieved partial success: the court found that the publication was unlawful had taken place, but did not convict the defendants. Another lawsuit followed against the editor in charge of the magazine Satyr over a caricature of the bathing scene with a text that contained a play on words with the name of the corpulent president and a boar . The editor was acquitted that his satire was essentially no insult. The swimming trunks allusions continued. In 1923 the journalist Joseph Roth regretfully stated: “‹ Ebert in bathing trunks ›became the most effective, because it was the most rabid, argument against the republic."

Kapp putsch

After the dissolution orders against the Freikorps Marine Brigade Ehrhardt and Marine Brigade von Loewenfeld , which were interspersed with right-wing extremists , General Walther von Lüttwitz protested and on March 10, 1920 tried to get Ebert to withdraw the order. Ebert rejected this request, as did Lüttwitz's demands for the dissolution of the National Assembly and new elections for the Reichstag and Reich President. Reichswehr Minister Noske relieved Lüttwitz of his office. This meant that the latter was forced to start the putsch that had already been planned together with Wolfgang Kapp early. It soon became apparent that Reichswehr commander General Hans von Seeckt and most of the troops were abandoning the government and declaring themselves neutral.

That is why on the night of March 12th and 13th, 1920, a joint appeal by the Reich President, the Social Democratic members of the government and the SPD executive committee for a general strike against the putschists Kapp and Lüttwitz appeared. In retrospect, the social democratic members of the government stated that they had not known anything about the appeal and accused the Reich Press Chief Ulrich Rauscher of acting alone. Heinrich August Winkler thinks it is certain that at least Gustav Noske and Otto Wels knew and approved the text before it was published. On the other hand, Bauer, Ebert and the other ministers were not informed.

The general strike paralyzed large parts of the economy and traffic. Most of the officials also supported the Bauer government and refused to obey Kapp. In addition to opportunistic reasons, genuine loyalty and respect for Ebert also played a role among the under-secretaries who spoke in favor of the higher civil service. The strike and the government-loyal attitude of the officials caused the coup to collapse after five days.

After the failure of the coup, however, the crisis was not over. In the Ruhr area, the Red Ruhr Army , supported by the USPD, fought for the rapid socialization of heavy industry. Scheidemann, the SPD executive committee, the trade unions and even parts of the civil service demanded that Noske be dismissed. Ebert wanted to keep him as possible and threatened to resign. The unions also called for socialization and other far-reaching structural reforms. In Ebert's view, these demands contradicted the constitution. Ebert responded to the growing demand for a new government to be formed with the condition that “he must be given the freedom to form the cabinet”. The previous government agreed, and Ebert appointed Hermann Müller as the new Chancellor. The attempt by the unions to gain significant influence over the government had ultimately failed due to Ebert's resistance. However, he had to drop Noske as part of the cabinet reshuffle.

With Ebert's backing, Reichswehr troops and free corps brutally crushed the uprising of the Red Ruhr Army . The movement for the socialization of heavy industry flagged after this defeat. As the Reichstag elections showed, a political shift to the right prevailed throughout the Reich.

Unstable governments

The Reichstag election of June 6, 1920 brought the Weimar coalition and especially the SPD considerable losses. The USPD, DNVP and DVP in particular were strengthened . Ebert commissioned Hermann Müller again to form a government. In the Reichstag parliamentary group on June 13th, however, the latter spoke out, as did Scheidemann, Otto Wels , Otto Hue and Otto Braun, against renewed participation by the SPD in government; only Eduard David and Eduard Bernstein advocated it. In vain did they demand, in Ebert's spirit, not to give up the government position voluntarily and expressed the fear that the social gains of the revolution could not be defended. The attitude of the SPD forced Ebert to form a bourgeois minority government from the center, DVP and DDP with the center politician Constantin Fehrenbach as Reich Chancellor. However, this broke apart again in May 1921 against the backdrop of the London ultimatum . Ebert was now aiming for a Weimar coalition again. In order to achieve this goal in the SPD, he again threatened to resign. Although the SPD refused to take over the Reich Chancellery, it was represented in the government of Joseph Wirth with important departments.

According to the constitution, the Reich President should actually be elected by the people. According to Art. 180 S. 2 WRV, Ebert exercised his office as Reich President elected by the National Assembly until the first popularly elected Reich President took office. Ebert himself wanted to end this transition period quickly and, from June 1920 onwards, had repeatedly urged that the election be scheduled. Due to the permanent crisis of the republic, in which the Reich President had special responsibility according to Art. 48 WRV, the date was postponed again and again. In addition, there were fundamental concerns as to whether the people were mature enough to vote on the filling of such an important office. In the wake of the pro-republican demonstrations after the murder of Walter Rathenau , the Wirth cabinet agreed in early October 1922 on December 3 as the election date. Ebert would be supported by the DDP and the center . In mid-October, the DVP demanded that the election be postponed until the 1924 Reichstag elections. The background was that the DNVP had brought Hindenburg into play as a common bourgeois candidate. Gustav Stresemann , on the one hand, did not want to lead a presidential election campaign against the DNVP in order, as he put it in retrospect, to avoid “the great test of strength between republic and monarchy”. On the other hand, he did not want to oppose Ebert in order not to endanger the DVP's entry into a grand coalition such as that which Ebert was striving for. While Ebert held back in this conflict, the parliamentary groups of SPD, DDP, Zentrum, DVP and BVP agreed to extend Ebert's term of office through a law amending Article 180 of the Imperial Constitution until June 30, 1925, which was October 24 1922 was passed with a constitutional majority. According to Christoph Gusy Ebert, the fact that Ebert was only elected by parliament did not at any time affect “political weight as the founder of the republic and bearer of her will to assert herself”.

The Wirth government fell apart at the end of 1922. Since a government with a parliamentary majority could not be formed, Ebert appointed Wilhelm Cuno , the director general of the Hapag group who is closely related to the DVP , as Reich Chancellor. This formed a "cabinet of business", based only on the center, BVP and DVP. This appointment turned out to be a wrong decision by Ebert, as Cuno was not up to the task.

Crisis year 1923

The year 1923 was marked by various crisis areas, some of which were closely related. The conflict over the reparation payments of the German Reich culminated in the occupation of the Ruhr area by French and Belgian troops. The German government declared passive resistance to this. The cost of the so-called Ruhr War fueled inflation once again. The German currency actually collapsed. The industrialists on the Rhine and Ruhr, especially Hugo Stinnes , showed themselves determined to negotiate with France if necessary without regard to the imperial government. There were separatist tendencies in the Rhineland. In Saxony and Thuringia there were Popular Front governments made up of the KPD and SPD, which increasingly came into conflict with the Reich government. In Saxony, communist members of the government called for the establishment of a proletarian dictatorship. In Bavaria , the State Commissioner General Gustav Ritter von Kahr worked with right-wing extremist organizations including the NSDAP . In doing so, he repeatedly opposed the decisions of the Reich government and worked towards their overthrow and a dictatorship.

Conflict over currency reform and social policy

The Cuno cabinet lasted until August 1923. In view of the failure of the Ruhr struggle, the parties supporting the Chancellor were also ready to form a new government. Ebert's goal was to form a grand coalition from the SPD to the DVP. Since the political right would not have recognized a social democratic head of government, Ebert appointed Gustav Stresemann , the chairman of the DVP, as Reich Chancellor. Stresemann stopped fighting against the Ruhr and took the first steps on the way to currency reform .

With regard to rapprochement with France, Stresemann was able to rely primarily on Ebert and the SPD. In solving the domestic political problems, on the other hand, there were considerable differences between the SPD and Stresemann, which Ebert was unable to resolve. In contrast to the decision of a cabinet meeting chaired by Ebert, which decided to treat the restructuring of the Reich finances on the one hand and the stabilization of the currency on the other hand, the government later decided the opposite. The currency reform was now inextricably linked with social cuts such as the abolition of the eight-hour day . The bourgeois parties also wanted Ebert to legitimize the Chancellor in this sense by invoking Article 48 of the Imperial Constitution, while the SPD insisted on an orderly legislative procedure for social policy issues.

This conflict led to the rupture of Stresemann's first cabinet on October 3, 1923. Ebert, however, reappointed Stresemann as head of government and put pressure on the SPD to rejoin the grand coalition. Under pressure from Ebert, the SPD also essentially gave way in terms of content and approved the solution to the crisis through the emergency ordinance in accordance with Art.

Dispute over Bavaria and Saxony

No sooner had this problem been overcome than serious conflicts arose again in the coalition over the treatment of Saxony and Bavaria. Both state governments had completely or partially distanced themselves from the constitutional order. But the right-wing parties pushed through the violent execution of the Reich against the left-wing governments in Saxony and Thuringia, with Ebert's approval, in accordance with Article 48 of the constitution. The right-wing parties refused to do the same in the case of Bavaria, arguing that the government was too weak for that. Ebert ultimately agreed with this stance. As a result, there was a clear estrangement between Ebert and his party.

One aspect of Ebert's decision was his fear that General Hans von Seeckt could use the situation to establish a military dictatorship. In order to take the wind out of Seeckt's sails, Ebert temporarily transferred the entire executive power to him in accordance with Article 48, on condition that he expressly assured the Reich President of his loyalty. As a result, Seeckt was separated from the Bavarian monarchists and from the supporters of a dictatorship in the Reichswehr leadership and, contrary to his intentions, was forced to help suppress the Hitler-Ludendorff putsch in Munich.

The coalition broke up in the conflict over the states of Bavaria, Saxony and Thuringia. The SPD now went into the opposition, and Ebert formed a cabinet around the central politician Wilhelm Marx . Ebert's reputation in the SPD and the workforce as a whole suffered considerably from the events of 1923. He had helped to eradicate central socio-political achievements of the revolution. On the other hand, it was possible to stabilize the currency in 1923/24 ( currency reform 1923 ), to get government spending under control and to introduce approaches to easing reparations with the Dawes Plan . It was not least thanks to Ebert that parliamentary democracy survived its worst crisis to date.

Magdeburg Trial and Death

Ebert's last few months were marked by a political defeat. An editor of the Central German Press accused him of contributing to the war defeat through his behavior before and after the end of the war. In the course of the insulting process that Ebert had brought before the Magdeburg district court , his secret agreement with General Wilhelm Groener became public. Ebert's behavior during the January strike in 1918 was also discussed. Ebert emphasized that he had only allowed himself to be elected to the strike commission in order to end the strike as quickly as possible. On December 23, 1924, the court sentenced the journalist for insulting the head of state, but stated in the grounds for the verdict that his allegation that Ebert had committed treason as a participant in the January strike was correct in the criminal sense. Despite the advocacy of well-known personalities and the Reich government for Ebert, the Magdeburg judgment confirmed the anti-democratic camp in its hatred of the republic. Ebert was only rehabilitated posthumously in 1931 by the Reich Court .

In consideration of his ongoing trial, Ebert had delayed the surgical treatment of an appendicitis that had become acute in February 1925 by August Bier . At the age of 54 he succumbed on February 28th at 10:15 am to the peritonitis (inflammation of the peritoneum) , diagnosed during the operation on February 23rd, caused by an appendix perforation ("appendix rupture" ). He was buried in his hometown in the Heidelberg Bergfriedhof . The "exceptionally large-scale, a statesman worthy" grave complex is located in the new department V and includes the area 84/84 A, B, C, D, E, F, G and H as well as the area 85/85 A, B, and C. at the funeral on March 5, 1925 held Willy Hellpach as president of Baden , Heidelberg's mayor Ernst Walz , the SPD chairman Hermann Müller, the Baden Landtag President Eugen Baumgartner and Theodor Leipart as ADGB -President grave speeches . Although Ebert had been baptized as a Catholic and left the church, the Protestant theologian Hermann Maas , pastor at Heidelberg's Heiliggeistkirche , also gave a funeral speech. Maas was reprimanded for this by superiors.

Classification and assessment

Ebert has been highly controversial since taking office as SPD chairman. On the one hand there was admiration and admiration for the representative of the "common people", who had worked his way up from a humble background to become the leader of the largest and most progressive party. Ebert retained his reputation as a unifying “red emperor” well into the November Revolution.

After his decision to deploy the military against revolutionary workers and “council republics ” across the empire , the radical left regarded him as a “traitor of the working class”, “reactionary militarist” and “agent of the bourgeoisie ”. For right-wing and right-wing extremists, on the other hand, he was regarded as the “renunciation politician” who was largely responsible for the capitulation of the German Reich and the signing of the Versailles Treaty (“ November criminal ”, “traitor”). This rejection also extended to the Weimar Constitution, which Ebert stood for.

His political imprint had grown in the empire and remained attached to it. He embodied the type of realpolitiker who used the given legal leeway to achieve small, step-by-step improvements for the bulk of the wage-earning population - he was never a revolutionary. According to Max von Baden, on November 9, 1918, Ebert said of the revolution : But I don't want it, I hate it like sin. Ebert was actually striving for a parliamentary monarchy, which he saw achieved with the October reform of October 5, 1918. His understanding of “ socialism ” did not envisage any interventions in the relations of production , although this would have corresponded to the SPD's Erfurt program, which is still valid. Rather, he relied on a collective safeguard for working hours and pension entitlements of the workers in the tradition of Bismarck's social laws.

His distrust was directed primarily towards the radical left revolutionaries and the supporters of the Bolsheviks. In order to fend off this and ensure democratic development, he worked with opponents of social democracy: the imperial officer corps and generals of the Supreme Army Command . In October 1918 they invited him to participate in power in order to evade their own responsibility for the war defeat and its consequences.

Ebert alienated the SPD leadership from a part of its electorate that did not want to give up the original party goals. However, the “division of the working class” - more precisely, its political representation - had already begun before the First World War and was based on fundamentally different views about the right political path.

In the historical scholarly discussion of Ebert and the November Revolution, the main question is whether, for example, the later development of the republic would not have been better through more radical changes in the civil service. Gerhard A. Ritter and Susanne Miller were of this opinion . Hagen Schulze, on the other hand, rejects the criticism of bureaucratic continuity, because a highly differentiated modern state like Germany could not have existed “without the extremely complex network of highly qualified administrative experts”. Even in Russia the previous administration was taken over by the Bolsheviks "almost en bloc". The problem in Germany was that they later renounced strict control and application of the new standards. Even Heinrich August Winkler emphasized the factual impossibility of certain claims of the radical left, and not even the Free Trade Unions were thinking of "interference with the existing property ownership". Nevertheless, Winkler believes that the renouncement of changes went further “than the circumstances required.” So there was not even any attempt to build the army in line with the republic.

Afterlife

Honors

- The Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung , which is close to the SPD , carries out research, educational work, student funding and international development cooperation.

- The federally direct foundation Reichspräsident-Friedrich-Ebert-Gedenkstätte , one of the six politicians memorial foundations , maintains the Reichspräsident-Friedrich-Ebert-Gedenkstätte in Heidelberg .

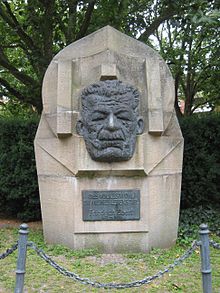

- Honorary grave at the Heidelberg Bergfriedhof : A large altar stone made of shell limestone bears the inscription under the name Friedrich Ebert: “The people's well-being is my work goal”. Stylized imperial eagles form the corners of the block. A high cross with a Corpus Christi rises behind the stone. Next to the stone block is a commemorative plaque that commemorates the two sons who died in World War I: Georg Ebert and Heinrich Ebert, who are buried in France.

- Naming of numerous streets and squares throughout Germany, e.g. B. Friedrich-Ebert-Platz with a monument in Dortmund - Hörde , Friedrich-Ebert-Siedlung , Friedrich-Ebert-Platz (Nuremberg) and schools .

- See also: Friedrich-Ebert-Straße , Ebertstraße , Friedrich-Ebert-Platz , Ebertplatz , Friedrich-Ebert-Allee , Friedrich-Ebert-Siedlung , Friedrich-Ebert-Park and Ebertpark

Representation in film and television

- In Kurt Maetzig's monumental film Ernst Thälmann - Son of His Class from 1954, Ebert was portrayed by Karl Weber (1898–1985).

- In Alfred Braun's feature film Stresemann , Ebert was portrayed by Paul Dahlke .

- In Hermann Kugelstadt's television film Friedrich Ebert - Birth of a Republic from 1969, Ebert was portrayed by Kurd Pieritz .

- Christian Redl plays Ebert in the 2018 television film Kaisersturz .

literature

- Wolfgang Abendroth : Friedrich Ebert. In: Wilhelm von Sternburg: The German Chancellors. From Bismarck to Kohl. Aufbau-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-7466-8032-8 , pp. 145–159.

- Waldemar Besson : Friedrich Ebert - merit and limit. Musterschmidt, Göttingen 1963.

- Bernd Braun / Walter Mühlhausen (eds.): From the workers' leader to the Reich President. Friedrich Ebert (1871-1925). Catalog for the permanent exhibition in the Reich President Friedrich Ebert Memorial . Foundation Reichspräsident-Friedrich Ebert-Gedenkstätte, Heidelberg 2012, ISBN 978-3-928880-42-8 .

- Friedrich Ebert. His life, his work, his time. Accompanying volume to the permanent exhibition in the Reichspräsident-Friedrich-Ebert-Gedenkstätte, ed. and edit v. Walter Muhlhausen. Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 1999, ISBN 3-933257-03-4 .

- Friedrich Ebert. 1871–1925: from workers' leader to President of the Reich. Exhibition of the Reichspräsident-Friedrich-Ebert-Gedenkstätte Foundation, Heidelberg and the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Bonn; Booklet with the main texts of the exhibition, ed. by Dieter Dowe . Research institute of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, historical research center. (= History discussion group. 9). 1st edition. 1995, ISBN 3-86077-379-8 . (online) (5th edition. Bonn 2005, ISBN 3-89892-347-9 )

- Sebastian Haffner : The betrayal - Germany 1918/19. Verlag 1900, Berlin 1968 u.ö., ISBN 3-930278-00-6 .

- Henning Köhler : Germany on its way to itself. A story of the century. Hohenheim Verlag, Stuttgart / Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-89850-057-8 .

-

Eberhard Kolb (Ed.): Friedrich Ebert as President of the Reich - Administration and understanding of office. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-486-56107-3 . In this:

- Ludwig Richter: The Reich President determines the policy and the Reich Chancellor covers it: Friedrich Ebert and the formation of the Weimar coalition.

- Walter Mühlhausen: The office of the Reich President in the political dispute.

- Eberhard Kolb: From the "provisional" to the definitive Reich President. The dispute over the "popular election" of the Reich President 1919–1922.

- Bernd Braun: Integration through representation - The Reich President in the federal states.

- Heinz Hürten: Reich President and Defense Policy. On the practice of personnel selection.

- Ludwig Richter: The presidential emergency ordinance law in the first years of the Weimar Republic. Friedrich Ebert and the application of Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution.

- Walter Mühlhausen: Reich President and Social Democracy: Friedrich Ebert and his party 1919–1925.

- Georg Kotowski : Friedrich Ebert. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 4, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1959, ISBN 3-428-00185-0 , pp. 254-256 ( digitized version ).

- Werner Maser : Friedrich Ebert. The first German Reich President. Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-548-34724-X .

- Walter Mühlhausen: Friedrich Ebert . Dietz, Bonn 2018, ISBN 978-3-8012-4248-0

- Walter Mühlhausen: Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. President of the Weimar Republic. Dietz, Bonn 2006, ISBN 3-8012-4164-5 . ( Review by Michael Epkenhans In: Die Zeit . Feb. 1, 2007)

- Walter Mühlhausen: The republic in mourning. The death of the first Reich President Friedrich Ebert. Reichspräsident-Friedrich-Ebert-Gedenkstätte Foundation, Heidelberg 2005, ISBN 3-928880-28-4 .

- Heinrich August Winkler : Weimar 1918–1933: The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-406-37646-0 . (4th revised edition. Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-44037-1 )

- Peter-Christian Witt : Friedrich Ebert: Party leader - Reich Chancellor - People's Representative - Reich President. 3rd, revised and updated edition. Verlag JHW Dietz Nachf., Bonn 1992, ISBN 3-87831-446-9 .

- historical:

- Emil Felden : One Man's Way - A Fritz Ebert novel. Friesen-Verlag, Bremen 1927.

- Paul Kampffmeyer : Fritz Ebert . Publishing house JHW Dietz, Weimar 1923.

Web links

- Literature by and about Friedrich Ebert in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Friedrich Ebert in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Friedrich Ebert in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Friedrich Ebert in the database of members of the Reichstag

- Friedrich Ebert's biography . In: Heinrich Best : Database of the members of the Reichstag of the Kaiserreich 1867/71 to 1918 (Biorab - Kaiserreich)

- Kai-Britt Albrecht: Friedrich Ebert. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Friedrich Ebert in the online version of the Reich Chancellery Edition Files. Weimar Republic

- Ebert memorial

- Friedrich Ebert and the signing of the Weimar Constitution in Schwarzburg

- The funeral ceremony of President Friedrich Ebert in Berlin and Heidelberg. In: Wiener Bilder , March 15, 1925, p. 5 (online at ANNO ).

- Magdeburg Trial of President Friedrich Ebert - the Erwin Rothardt case , online encyclopedia of political criminal trials

Individual evidence

-

↑ Friedrich Ebert chronological table .

Reichstag Handbook 1912, p. 237 . - ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 26 f .; Maser, pp. 15-20.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 29 f.

- ↑ Adolf Hitler: Mein Kampf. Munich 1926, p. 286.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 34 f.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 32 f.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 46.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 39.

- ↑ Walter Mühlhausen calls him a “multifunctional” in relation to his activities in Bremen (Walter Mühlhausen: Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. President of the Weimar Republic. Pp. 52 and 58.)

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 44 ff.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 46 ff.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 50 ff.

- ^ On this, Walter Mühlhausen: Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. President of the Weimar Republic. P. 61 and p. 70.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 39 ff. On Ebert's aversion to theoretical debates also Walter Mühlhausen: Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. President of the Weimar Republic. P. 56, P. 58, P. 65 and P. 69.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 54 ff.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 57 ff.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 60 ff.

- ↑ For contacts in the direction of the free trade unions and for joint youth work by the party and trade unions, see Walter Mühlhausen: Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. President of the Weimar Republic. Pp. 59-61; also Witt, 62 f.

- ↑ See Walter Mühlhausen: Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. President of the Weimar Republic. P. 63 f; see also Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 62 f.

- ↑ For Ebert's board work up to his election to the Reichstag, see Walter Mühlhausen: Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. President of the Weimar Republic. Pp. 58–65 and Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, pp. 60-64.

- ↑ D. Engelmann, H. Naumann: Hugo Haase, p. 16.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 63 f.

- ^ Imperial Statistical Office (ed.): The Reichstag elections of 1912. Issue 2, Verlag von Puttkammer & Mühlbrecht, Berlin 1913, p. 94 (Statistics of the German Reich, Volume 250).

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 66 f.

- ^ Walter Mühlhausen: Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. President of the Weimar Republic. Dietz, Bonn 2006, p. 68.

- ↑ On the election to the Reichstag, on work in the Reichstag and on the election of party chairman, see Walter Mühlhausen: Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. President of the Weimar Republic. Pp. 65-70; furthermore Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, pp. 64-68.

- ↑ Quoting Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 74.

- ↑ To this fundamentally Karl-Heinz Klär : The collapse of the Second International. Campus-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1981, ISBN 3-593-32925-5 .

- ^ Hajo Holborn : German history in modern times . Volume 3: The Age of Imperialism (1871–1945) . Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 1871, ISBN 3-486-43251-6 , p. 204.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 72 ff.

- ↑ D. Engelmann, H. Naumann: Hugo Haase. Berlin 1999, p. 31f.

- ↑ D. Engelmann, H. Naumann: Hugo Haase. Berlin 1999, p. 34.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 76 ff.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 78 ff.

- ↑ D. Engelmann, H. Naumann: Hugo Haase. P. 37.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 82 ff.

- ↑ Quoted from Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 85.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 86 f.

- ↑ Quoted from Walter Mühlhausen: Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. President of the Weimar Republic. P. 100. Also with Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993, p. 22.

- ↑ Quoted from Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 102; see ders., p. 100 ff.

- ^ Walter Mühlhausen: Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. President of the Weimar Republic. P. 88.

- ↑ D. Engelmann, H. Naumann: Hugo Haase. P. 56 f.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 109 ff.

- ^ On this, Walter Mühlhausen: Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. President of the Weimar Republic. P. 113.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler : Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy , Beck, Munich 1993, p. 38.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 113 ff.

- ^ On this, Walter Mühlhausen: Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. President of the Weimar Republic. P. 106 f.

- ^ Hagen Schulze : Weimar. Germany 1917–1933 (= The Germans and their Nation , Volume 4), Siedler, Berlin 1994, p. 161.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler : Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993, p. 53 f.

- ^ Ulrich Kluge: Soldiers' Councils and Revolution. Studies on military policy in Germany 1918/19. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1975, pp. 263 and 265.

- ^ Walter Mühlhausen: Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. President of the Weimar Republic. JHW Dietz Nachf., Bonn 2006, p. 142 f.

- ^ Hagen Schulze: Weimar. Germany 1917–1933 (= The Germans and their Nation. Volume 4). Siedler, Berlin 1994, p. 177 f.

- ↑ Quoted from Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 136; see ders., p. 134 ff.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 138 ff.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 148 ff.

- ^ Also on the following see Walter Mühlhausen: The Weimar Republic bare. The swimwear photo by Friedrich Ebert and Gustav Noske. In: Gerhard Paul (ed.): The century of pictures. Volume 1: 1900-1949. Special edition for the Federal Agency for Civic Education, Bonn 2009, pp. 236–243 (here the quote)

- ↑ Niels Albrecht: The power of a smear campaign. Anti-democratic agitation by the press and the judiciary against the Weimar Republic and its first Reich President Friedrich Ebert from the “Badebild” to the Magdeburg trial. Dissertation. Bremen 2002, pp. 45–88 ( online (PDF; 3.7 MB), accessed on July 3, 2010)

- ^ Cover picture of the BIS from August 21, 1919 on einestages.spiegel.de, accessed on June 29, 2010.

- ^ Bernhard Fulda: The politics of the "unpolitical". The tabloid and mass press in the twenties and thirties. In: Frank Bösch , Norbert Frei (Ed.): Medialization and Democracy in the 20th Century. Wallstein, Göttingen 2006, p. 66.

- ↑ Bernd Braun: The Reich President in the countries. In: Eberhard Kolb (ed.): Friedrich Ebert as Reich President. Administration and understanding of office. Oldenbourg, Munich 1998, p. 161.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-406-37646-0 , p. 122.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 158 ff.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 162 ff.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 166 ff.

- ↑ a b Christoph Gusy : The Weimar Imperial Constitution . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1997, p. 99.

- ↑ Thomas Raithel: The difficult game parliamentarism. German Reichstag and French Chambre des Députés during the inflation crises of the 1920s . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 2005, pp. 141-143.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 170 f.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 171 ff.

- ^ Witt: Friedrich Ebert. 1992, p. 176 f.

- ↑ See Heinrich August Winkler: The appearance of normality. Workers and the labor movement in the Weimar Republic. 1924 to 1930. Dietz, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-8012-0094-9 , p. 229, with further references

- ^ Eberhard Kolb (Ed.): Friedrich Ebert as President of the Reich: Administration and understanding of office. 1997. p. 307.

- ↑ Malte Wilke, Stefan Segerling: Politized Insult Processes in the Weimar Republic , Journal on European History of Law , Vol. 10, 2019, Issue 1, pp. 31–39, there p. 32 ff., Online

- ↑ Ernst Kern : Seeing - Thinking - Acting of a surgeon in the 20th century. ecomed, Landsberg am Lech 2000, ISBN 3-609-20149-5 , p. 202.

- ^ Friedrich Winterhager : The death of the Reich President Friedrich Ebert (1925). In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 9, 1991, pp. 105-113.

- ↑ Leena Ruuskanen: The Heidelberg Bergfriedhof through the ages . Ubstadt-Weiher 2008, ISBN 978-3-89735-518-7 , pp. 188 ff.

- ^ See Walter Mühlhausen, Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. President of the Weimar Republic. P. 977f. and Werner Keller: Hermann Maas. Pastor of the Holy Spirit and bridge builder. In: Gottfried Seebaß, Volker Sellin, Hans Gercke, Werner Keller, Richard Fischer (eds.): The Church of the Holy Spirit in Heidelberg 1398–1998 . Umschau Buchverlag, 2001, ISBN 3-8295-6318-3 , p. 108 ff.

- ^ Hagen Schulze: Weimar. Germany 1917–1933. (= The Germans and their nation. 4). Siedler Verlag, Berlin 1982, p. 165.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: The long way to the west. Volume I: German history from the end of the Old Reich to the fall of the Weimar Republic . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2000, p. 382.

- ↑ Fall of the Kaiser . ( zdf.de [accessed November 19, 2018]).

- ↑ Excerpt from: books.google.de

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ebert, Friedrich |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | German politician (SPD), MdBB, MdR, Reich President of the Weimar Republic |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 4, 1871 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Heidelberg |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 28, 1925 |

| Place of death | Berlin |