German Army (German Empire)

|

|||

Stand of the German Emperor, the Supreme Warlord |

|||

| guide | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Commander in Chief de jure : |

The Kaiser (in times of peace with the exception of the Bavarian army contingent ) last: Wilhelm II. |

||

| Commander in chief de facto : | until 1914: The Kaiser from 1914: Chief of the General Staff of the Field Army, lastly: Paul von Hindenburg |

||

| Headquarters: |

Imperial Headquarters in Berlin 1914/18: Large Headquarters |

||

| Military strength | |||

| Active soldiers: | 794,000 as of 1914 |

||

| Conscription: | See subsection | ||

| Eligibility for military service: | Age 17 and over | ||

| Share of soldiers in the total population: | Between 1% (year 1890) and 1.20% (year 1914) | ||

| household | |||

| Military budget: | 2,224 million marks as of 1914 |

||

| history | |||

| Founding: | 1871 | ||

| Replacement: | January 19, 1919 ( Peace Army ) | ||

German Army was the official designation of the land forces of the German Empire from 1871 to 1918. The constitution of the German Empire also uses the term “Reichsheer” based on the federal army of the North German Confederation.

The commander in chief of the German Army was the Kaiser. The troop contingents of the German federal states were under Prussian command due to military conventions or were incorporated into the Prussian army . Exceptions were the armies of the kingdoms of Bavaria , Saxony and Württemberg . When they joined the North German Confederation, these states had negotiated so-called reserve rights or agreed corresponding regulations with Prussia .

The Bavarian , Saxon and Württemberg armies were under the orders of their respective sovereigns in peacetime. Their administration was under their own war ministries. The Saxon and Württemberg armies each formed a self-contained army corps within the German army. The Bavarian Army provided three of its own army corps and was not included in the numbering of the troop units in the rest of the army. The contingents of the smaller German states generally formed closed units within the Prussian army. Württemberg assigned officers to the Prussian army for training purposes . Only Bavaria had its own war academy alongside Prussia . The separation by country of origin was relaxed under the necessities of the First World War , but not given up.

Even in peacetime the emperor had the right to determine the strength of the presence, to determine the garrisons, to build fortresses and to ensure uniform organization and formation, armament and command, as well as the training of men and officers. The military budget was set by the parliaments of the individual states. As armed forces outside the army, the protection troops of the German colonies and protected areas and the navy including its three sea battalions were under the direct command of the emperor and the administration of the empire.

After the defeat of 1918, the army, which was already largely demobilized, had to be reduced to a peace force of 100,000 men due to the Peace Treaty of Versailles . From his remains and some volunteer corps that was Reichswehr erected.

Overview

The army and the navy were subordinate to the emperor. A parliamentary control was carried out through the approval of the financial means by the Reichstag . The limits of the “power of command ” were hardly defined, however, and effective control by parliament was difficult. Below the "supreme warlord" (the emperor) there were three institutions, the military cabinet , the Prussian war ministry and the general staff , which at times fought among themselves over competencies. The General Staff in particular tried - already under Helmuth Karl Bernhard von Moltke and later Alfred von Waldersee - to influence political decisions. The same applies to Alfred von Tirpitz on naval issues.

The close ties with the monarchy was reflected in the initially very strong noble dominated officer corps resist. Even later, the nobility retained a strong position, especially in the higher ranks. However, with the enlargement of the army and the navy, the bourgeois share increased more and more. The role model function of the nobility, in addition to internal socialization in the military, ensured that the self-image of the bourgeois group hardly differed from that of the noble officers.

Between 1848 and the 1860s, society viewed the military with rather suspicion. This changed after the victories in the German Wars of Unification between 1864 and 1871. The military became an element of the emerging imperial patriotism. Criticism of the military was considered improper. However, the parties did not support an expansion of the army indefinitely. For example, it was not until 1890 that the armed power reached its constitutional strength of one percent of the population, with a peace presence of almost 490,000 men (for comparison: before reunification, the Bundeswehr accounted for around 0.9 percent and that of the armed organs of the GDR around 1.5 percent of the population. Today it is only 0.3 percent in reunified Germany). In the following years the land forces were further strengthened. Between 1898 and 1911, the expensive armament of the navy imposed restrictions on the land army. It is noteworthy that at this time the General Staff itself opposed an increase in troop strength because it feared an increase in the bourgeois element at the expense of the noble element in the officer corps. During this time, the Schlieffen Plan developed the concept for a possible two-front war against France and Russia , taking into account the participation of Great Britain on the side of the opponents. After 1911, armaments were intensively promoted. The troop strength required for the implementation of the Schlieffen Plan was ultimately not achieved.

The army gained strong social prestige during the empire. The officer corps was regarded by the leading parts of the population as the “first estate in the state”. Its view of the world was shaped by loyalty to the monarchy and the defense of the rights of the king; it was conservative, anti-socialist and fundamentally anti-parliamentary. The military code of conduct and honor had a deep impact on society. For many citizens, too, the status of reserve officer has now become a desirable goal.

The military was undoubtedly also of importance for the internal formation of nations. The joint service improved the integration of the Catholic population into the predominantly Protestant empire. Even the workers did not remain immune to the military radiance. The long military service of two or three years at the so-called “School of the Nation”, as which one began to see the army, played a formative role.

All over the empire the new war clubs became carriers of military values and a militarist worldview. The 2.9 million membership of the Kyffhäuserbund in 1913 shows the widespread effect these groups had . The Bund was thus the strongest mass organization in the Reich. The associations sponsored by the state should cultivate a pious military, national and monarchical attitude and immunize the members against social democracy.

history

The German Empire was the North German Confederation, reformed in 1870 . Its constitution brought about the unification of the armed forces by integrating the troops of the smaller alliance states into the Prussian army. Only the Kingdom of Saxony was able to reserve special rights for its army when it joined the North German Confederation. During the war against France in 1870/71 , the southern German states, i.e. the Grand Duchies of Baden and Hesse , as well as the kingdoms of Bavaria and Württemberg, joined the North German Confederation.

However, the kingdoms of Württemberg and Bavaria retained some reservation rights , including maintaining their own army organization. Only in the event of an alliance, i.e. during war, was the Bavarian troops subordinate to them, while the Württemberg and Saxon troops were already subordinate to the Great General Staff in the peace. However, the administration of the Württemberg and Saxon troops was carried out by war ministries in Stuttgart and Dresden.

This coexistence was the cause of organizational difficulties at the beginning of the First World War, as the war ministries in Berlin, Stuttgart, Munich and Dresden had not coordinated their procurement and the equipment of the individual armies sometimes differed considerably. This finally led to the establishment of the “Standards Committee of German Industry” in 1917, the forerunner of the German Institute for Standardization and the well-known “DIN standards”.

Legal basis

The main features of the strength and organization of the German Army were laid down in particular by:

- the Imperial Constitution of April 16, 1871

- the alliance treaty between the North German Confederation and Bavaria of November 23, 1870

- the military convention between the North German Confederation and Württemberg from 21./25. November 1870

- the conventions between Prussia and Saxony of February 7, 1867

- the conventions between Prussia and the other federal states

- the Reich Military Law of May 2, 1874

- the laws relating to the strength of the peace presence of the German army.

Leadership principles

The Israeli military historian Martin van Creveld remarked in his book “Kampfkraft”: “In contrast to the widespread clichés of“ cadaver obedience ”and“ Prussian discipline ”, the German army had always had the decisive importance of initiative and initiative, at least since the time of the elder Moltke Emphasizes personal responsibility, even at the lowest level ” .

Since Friedrich II. The officers were consistently trained to act independently. Here is a quote from Frederick II:

"I made him a general so that he knows when to disobey."

An incident from the Battle of Zorndorf can be used as an example of the interpretation of Prussian obedience . Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz refused several times the order of the king to intervene with his cavalry units in the battle, although he was threatened with "his head will be liable for the outcome of the battle". Seydlitz only attacked when he could achieve maximum effect by attacking the flank. This contributed significantly to the victorious outcome of the battle. Seydlitz obeyed the command of his king not according to the word, but according to the meaning.

An accelerated development began in Prussia from 1806, from 1888 the order tactics with the " Exercise Regulations for the Infantry" became binding for the Prussian army and was taken over by the other German armies and later expanded by the Reichswehr .

Other elements were the principles such as “ leading from the front ”. Here, too, great independence and a sense of responsibility on the part of the soldiers were a prerequisite. The greater flexibility and reaction options were offset by the risk of the Führer being cut off and the high number of officer losses. Despite this risk, it was a firm principle in the German army.

Another principle from the drill regulations of 1888: "Failure to do so is more difficult than making mistakes in the choice of means". Behind this was the realization that hesitant and wait-and-see behavior is always worse than a, perhaps not optimal, action. The Prussian and German soldiers were trained to keep the initiative by all means. An English study after the Franco-Prussian War concluded as follows: "Nowhere are the independence of judgment and freedom of will, from the commanding general to the sergeant , so cultivated and promoted as in the German army". A sense of responsibility was the most important quality of leadership in the Prussian and German armies, and the deportation of responsibility was frowned upon.

In 1914, the SPD deputy in the Württemberg state parliament, Hermann Mattutat, wrote in the Socialist Monthly Bulletin : “Today's type of warfare differs enormously from that of earlier times. Above all, very considerable demands are made on the personality of officers and soldiers. A cadaver obedience would fail completely, since it does not enable any active actions without continued driving and supervision. Instead, soldiers today are required: perseverance, independence, good orientation skills, quick adaptation to the respective situation [...] and extensive initiative even without guidance. These are all qualities that can only be acquired through careful mental and physical training. "

Such leadership principles played their part in the evident operational superiority of the Prussian-German armies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Bundeswehr and other armed forces continue to be led according to this example. Modern management methods such as managing with goals by setting target agreements are based on these principles.

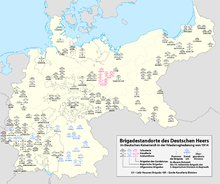

structure

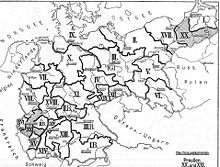

In peacetime, the highest level of leadership, training and administration was the Army Corps . The supervision of all measures taken by the Army Corps was the responsibility of the Army stage managers , who, on behalf of the Supreme Warlord, had only the right to inspect down to the lowest level, but had no management duties. The army stage managers appeared particularly at the annual maneuvers. For this, the army was divided into army inspections with assigned army corps. Originally there were five inspections, then eight in 1914. In the event of war, these inspections were reorganized into armies . The staff consisted of the army stage manager, a general staff officer and, if necessary, an adjutant and another officer; the seat was at the respective place of residence of the army stage manager.

In addition, there were general inspections and inspections of the branches of arms . They had to take care of matters specific to the type of weapon (equipment, reassembly, etc.).

| inspection | Location | inspected army corps |

|---|---|---|

| I. Army inspection |

Hanover , from 1900 Berlin , from 1914 Gdansk |

1871: I. Army Corps, II. Army Corps, IX. Army Corps, X. Army Corps from 1906: I. Army Corps, II. Army Corps, IX. Army Corps, X. Army Corps, XVII. Army Corps from 1914: I. Army Corps, II. Army Corps, XVII. Army Corps |

| II. Army inspection |

Dresden , from 1906 Meiningen , from 1914 Berlin |

1871: V. Army Corps, VI. Army Corps, XII. Army Corps from 1906: V. Army Corps, VI. Army Corps, XII. Army Corps, XIXth Army Corps from 1914: Guard Corps, XII. (1. Royal Saxon) Army Corps, XIX. (2nd Royal Saxon) Army Corps |

| III. Army inspection |

Darmstadt , from 1906 Hanover |

1871: VII. Army Corps, VIII. Army Corps, XI. Army Corps from 1906: VII. Army Corps, VIII. Army Corps, XI. Army Corps, XIII. Army Corps, XVIII. Army Corps from 1914: IX. Army Corps, X Army Corps |

| IV. Army inspection | Berlin, from 1906 Munich |

1871: III. Army Corps, IV. Army Corps assigned to I. Bavarian Army Corps, II. Bavarian Army Corps from 1906: III. Army Corps, IV. Army Corps assigned to I. Bavarian Army Corps, II. Bavarian Army Corps from 1914: III. Army Corps assigned to I. Bavarian Army Corps, II. Bavarian Army Corps, III. Bavarian Army Corps |

| V. Army inspection | Karlsruhe | 1871: XIV Army Corps, XV. Army Corps from 1906: XIV. Army Corps, XV. Army Corps, XVI. Army Corps from 1914: IX. Army Corps, XIV. Army Corps, XV. Army Corps |

| from 1908 VI. Army inspection |

Stuttgart | IV Army Corps, XI Army Corps, XIII (Royal Württemberg) Army Corps |

| from 1913 VII Army inspection |

Saarbrücken | XVI. Army Corps, XVII. Army Corps, XXI. Army Corps |

| from 1914 VIII. Army inspection |

Berlin | XI. Army Corps, XVIII. Army Corps, XX. Army Corps |

In addition, there was the General Inspection of the Cavalry from 1898 , to which the cavalry brigades of the divisions were not subordinate.

| inspection | Location |

|---|---|

| General inspection of the cavalry | Berlin |

| 1st cavalry inspection | Koenigsberg |

| 2nd cavalry inspection | Szczecin |

| 3rd cavalry inspection | Muenster |

| 4. Cavalry inspection | Saarbrücken, 1900/02 in Potsdam |

The 25 army corps, three of which were Bavarian with separate numbering, two from Saxony and one from Württemberg, were generally subordinate to two divisions . The total strength of an army corps was 1554 officers, 43,317 men, 16,934 horses and 2933 vehicles.

The divisions usually comprised two infantry brigades with two regiments each , one cavalry brigade with two cavalry regiments and one field artillery brigade with two regiments. An infantry regiment normally consisted of three battalions of four companies each, i.e. twelve companies per regiment. The rearmament in 1912/1913 brought about the establishment of a 13th (machine gun) company for almost all regiments. A cavalry regiment consisted of five squadrons , in Bavaria sometimes only four squadrons.

In addition, an army corps had one or two foot artillery regiments , a hunter battalion , one or two engineer battalions , a train battalion and, in some cases , various other units, such as a telegraph battalion , one or two field engineer companies, one or two medical companies, railway companies, etc. at their disposal as corps troops.

In 1900 an infantry regiment had a peacetime strength of 69 officers, 6 doctors, in 1977 NCOs and men and 6 military officials, a total of 2058 men. A cavalry regiment had 760 men and 702 service horses. This strength applied to regiments with a high budget. Medium- or lower-budget regiments were less powerful. An infantry company with a high budget had 5 officers and 159 NCOs and men, with a lower budget 4 officers and 141 NCOs and men.

In peacetime the cavalry had no corps, only one division, the Guard Cavalry Division . When mobilizing for World War I, the cavalry was divided into army cavalry and division cavalry .

In 1914 the Reichsheer comprised:

Bars

- 25 general commands

- 50 infantry divisions and 1 cavalry division

- 25 Landwehr inspections

- 106 infantry, 55 cavalry, 50 field artillery, 7 foot artillery and 2 railway brigades

infantry

- 651 infantry battalions in 217 regiments of three battalions each

- 18 hunter and rifle battalions

- 233 machine gun companies, one for each infantry regiment and one for 16 fighter battalions

- 11 MG divisions for the cavalry divisions to be formed upon mobilization

- 15 fortress machine gun detachments

- 9 NCO schools, 1 infantry training battalion, 1 infantry shooting school, 1 rifle examination committee

cavalry

- 547 cavalry squadrons in 107 regiments of five and 3 regiments of four squadrons

artillery

- 600 mobile and 33 mounted field artillery batteries in 100 regiments of two or three divisions each

- 1 teaching field artillery regiment of the field artillery shooting school

- 190 foot artillery batteries in 24 regiments of two battalions each

- 30 clothing departments of the foot artillery

- 1 teaching foot artillery regiment of the foot artillery shooting school

Pioneers

- 35 engineer battalions with 26 floodlights

- 9 pioneer commands for two subordinate engineer battalions each

Transport troops

- 8 railway battalions, 6 of them in 3 regiments of two battalions each, 2 independent

- 9 telegraph battalions

- 8 fortress telephone companies

- 5 airship battalions

- 5 air battalions

- 1 motor battalion

- 1 (Bavarian) Air and Motor Vehicle Battalion

Train

- 25 train departments

also

- 317 district commands

Development of the manpower of the German army at selected times:

| year | 1875 | 1888 | 1891 | 1893 | 1899 | 1902 | 1906 | 1908 | 1911 | 1913 | 1914 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| soldiers | 420,000 | 487,000 | 507,000 | 580,000 | 591,000 | 605,000 | 610,000 | 613,000 | 617,000 | 663,000 | 794,000 |

Military branches

In addition to the previous classic armies of infantry , cavalry and artillery , new armies arose due to technical developments, partly through the expansion of smaller units ( pioneers , train ), partly through the use of new technical devices and applications by the army.

Armament and equipment

No. 3911 of June 13, 1918, war number 202

The armament of the infantry consisted of the Gewehr 88 , later Gewehr 98 , both for the 7.92 × 57 mm cartridge; the Gewehr 88 did not prove itself and was relatively quickly replaced by the more powerful design of the Gewehr 98, the successor of which was carried in the carbine version as the main orderly weapon Karabiner 98k in World War II , and the side gun . Portepee NCOs had the so-called Reichsrevolver and the officer's side gun. Hunters carried a deer catcher instead of a side rifle . Rear-mounted and specialized troop units on foot were first equipped with a shortened version of the Gewehr 88, this was the Gewehr 91. Later this was replaced by a shortened version of the Gewehr 98, the Karabiner 98 Artillery. In order to create a uniform short weapon for mounted and unmounted troops, a standard carbine was created with the carbine 98A. Since the 98A carbine generated enormous muzzle flash because of its short barrel, an extended version was created with the 98AZ carbine. The Kar98AZ was mainly used by the storm troops in World War I and later renamed the Karabiner 98a (small a) in the Reichswehr.

In the cavalry there was held the rifle the carabiner 88 and 98 carbine cavalry and swords , sword knot-commissioned officers wore instead the officer saber. The lance was also used for this purpose. The Karabiner 88 was a shortened version of the Gewehr 88 and was given the name commissioning socket due to its whole stock. Because of the problem with the 88 system, a carbine version of the Gewehr 98 was introduced with the Karabiner 98 Kavallerie. Later, a uniform short version for infantry and cavalry was created with the 98A carbine.

uniform

Although the various contingents of the army were gradually equipped according to uniform specifications after the establishment of the empire, the principle of diversity in uniformity was followed for headgear, color and cut.

The distinguishing features were:

- Badge color and button color (the color of the braids , braids , and helmet fittings is usually based on this )

- Armpit flaps ( enlisted men and NCOs), shoulder boards (officers) and epaulettes

- Shape and fittings of the helmets

- Cockades

- Cuffs

Examples:

infantry

The tunic was single-breasted with eight buttons. The trousers were black, and white trousers were also worn in summer. Boots were the so-called "Knobelbecher" .

The infantry's tunic was dark blue, that of the hunters and riflemen dark green. The rifle (fusilier) regiment "Prince Georg" (Royal Saxon) No. 108 was the only association of line infantry to wear green tunics. The Bavarian infantry and the hunters wore light blue tunics. The machine gun departments wore gray-green tunics.

The German soldier was given a new uniform once a year , with a total of up to five sets. The first set was put on for parade , the second as a dress uniform, the third and fourth set for daily duty and the fifth set, if any, lay in the closet in case of war.

The contingents of most of the German states had already been incorporated into the Prussian army through military conventions or affiliated to it and only had small reservation rights , such as the right to their own cockades on the headgear, the various crests and other distinguishing features. Which contingent a soldier belonged to could be recognized by the country cockade of the headgear, the cuffs and the epaulettes. In 1914 there were a total of 272 different variations in uniforms. In some cases, it was just a matter of minor details (for example, only the Hessian Life Guard Infantry Regiment No. 115 had the button placket of the Gardelitzen not in the basic color of the cuffs, but underlaid in white. The five Hessian infantry regiments wore their sleeve flaps not the color of their (XVIII.) army corps , but each regiment had a different color, which, however, were jealously observed). The national colors appeared also in other clothing and badges such as epaulets , sashes , Portepees , Einjährigenschnüren and award buttons for non-commissioned officers and privates .

Saxony had the following deviations in particular: the epaulettes were angular, the advance on the front of the skirt was led around the lower lap edge of the skirt.

The basic headgear was the well-known " Pickelhaube ". Hunters , shooters and MG - departments wore a shako . For the parade the two Prussian guards regiments grenadier caps in old Prussian style. For some types of suits, the peaked cap or, for teams, also the " Kratzen " (cap without a peak) was ordered.

The uniforms remained largely unchanged until the outbreak of war. From 1897 onwards, in addition to the state cockade, the Reich cockade was also worn.

In 1907 the first field-gray uniform was introduced on a trial basis , which was only to be worn in the event of war, but had been used in maneuvers since 1909/1910. Until the beginning of the war and during the war, the field gray uniform underwent some changes; For example, the color was turned gray-green, but the name " field gray " was retained. During the World War only this "field gray" uniform was worn, initially the " Pickelhaube " with cover, from the middle of the war the steel helmet M1916 was introduced across the board.

cavalry

The cuirassiers wore a Koller white Kirsey with matching collar and epaulets, according to regiment with different colored cuffs, trimmings, advances and collar Patten. The cuirassiers' headgear was a spiked bonnet with a metal bell, the neck shield of which was pulled back low.

The heavy riders , to whom the cuirassiers had been converted in Saxony in 1876 and in Bavaria in 1879, wore cornflower-blue kollers (Saxony) or tunics. While the Saxons wore the Prussian cuirassier helmet, the Bavarians wore the leather helmet for mounted people.

The Uhlans wore a dark blue (in Saxony light blue, in Bavaria dark green) ulanka with epaulettes and collar, lapels and lugs, each with a badge-colored collar. A chapka was worn as headgear .

The dragoons wore a cornflower blue (in Hesse: dark green) tunic with badge-colored collars, lapels and epaulettes. Helmet for mounted men with a point (similar to that of the infantry).

The uniform of the Chevaulegers , which existed only in Bavaria, was similar to that of the Uhlans, but was dark green and had angular epaulettes and leather spiked bonnets.

The hussars wore an Attila in regimental colors with cord trimmings and armpit cords. The Kolpak served as headgear . Some regiments also wore fur .

The hunters on horseback , who were set up from 1901, wore a collar and tunic made of gray-green cloth. Epaulets and lapels were light green and set off with colored piping . Regiments No. 1 to No. 6 wore blackened cuirassier helmets and cuirassier boots. In Regiments No. 7 to No. 13, only the officers were equipped in this way, while the NCOs and men were equipped with dragoon helmets and dragoon boots. (The retrofitting with the cuirassier helmets did not take place until 1915, until then these helmets had not been available.)

Field-gray uniforms were introduced for field suits in 1909, in which the badge-colored elements were usually only piped in the corresponding color. Some of the newly established units, such as the Hussar Regiment No. 21, no longer received a colorful peace uniform. The hunters on horseback, who already had a slightly greener camouflage-colored uniform, kept it.

Artillery, train and technical troops

The artillery wore a dark blue tunic with black markings. Instead of the tip of the helmet, a ball was worn to avoid injuries, only in Bavaria the tip was worn here. The soldiers of the train wore dark blue tunics with light blue markings and a shako . In Saxony, the artillery, pioneers and train wore dark green tunics, the badges were red or light blue for the train.

Engineers and railroad troops wore the uniform of the artillery, but with white instead of yellow buttons. Airmen, airshipmen and telegraph troops wore the uniform of the artillery, but instead of the helmet the shako.

Standard

Bath. Foot artillery regiment No. 14 in Strasbourg (back side)

Ranks

Rank groups

There were six rank groups in the German Army :

- Teams (common)

- NCOs (with and without portepee )

- Subaltern officers ,

- Captains ,

- Staff officers and

- Generals .

The ranks of the Prussian Army formed the basis for the ranks of the German Army up to today's Bundeswehr .

| Foot troops | cavalry | artillery | description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teams | |||

| Grenadier, fusilier, hunter, musketeer, guardsman, infantryman, soldier, pioneer | Dragoons, hussars, hunters, cuirassiers, Ulan, horsemen, Chevaulegers | Gunner, driver | No authority. The soldier with no rank was also called the commoner . |

| Private | Private | Private | The private was the corporal's deputy. |

| unavailable | unavailable | Corporal / Bombardier | The corporal replaced the Bombardier NCOs in the Prussian foot artillery in 1859 . Both ranks usually distinguished the gunner . |

| NCOs without portepee | |||

| Sergeant / corporal | Sergeant / corporal | Sergeant / corporal | The corporal (1856 Sergeant ) commanded an up to 30-strong "squad". Three per company. Among the hunters, the NCO was called Oberjäger . |

| sergeant | sergeant | sergeant | Like the sergeant, the sergeant headed a corporal body. |

| NCOs with portepee | |||

|

Vice Sergeant /

Vice sergeant |

Deputy Sergeant /

Vice constable |

Deputy Sergeant /

Vice constable |

The rank was introduced throughout the army in 1873. In companies with no more than two officers, vice sergeants acted as platoon leaders - a position generally assigned to a lieutenant or first lieutenant. The salutation by soldiers of lower rank was always sergeant or sergeant . |

| regular sergeant | regular sergeant | regular sergeant | Highest rank of non-commissioned officer. The regular sergeant / sergeant was entrusted with internal service and administrative tasks ("Spieß" / "mother of the company") and worked closely with the company and battery chief. |

| Officer deputy | Officer deputy | Officer deputy | The service position was created in 1887. Active deputy sergeants and sergeants could be appointed after at least four years of impeccable leadership. Two posts per company were set up during the First World War. After the end of the war or in the event of a dismissal, the downgrade to the old rank was planned. The salutation was always "Vice Sergeant" (exception see above) or "Sergeant". |

| Ensign | Ensign | Ensign | Officer candidate in the rank of NCO. |

| Subaltern officers | |||

| Sergeant Lieutenant | Sergeant Lieutenant | Sergeant Lieutenant | Since 1877 the lowest officer rank. The sergeant lieutenant held the rank of lieutenant, but always ranked behind the holder of the "real" rank, as he did not have an officer license. Hybrid position between NCO and officer . The non-commissioned officers on leave (reserve) were intended for promotion, but not the "active" (ie professional) non-commissioned officers, who - albeit only in the event of war - could be promoted to regular officers. |

| Lieutenant / Second Lieutenant | Lieutenant / Second Lieutenant | Lieutenant /

Fireworks lieutenant |

Platoon leader, control of the practical service and the NCOs. |

|

First Lieutenant /

Premier lieutenant |

First Lieutenant /

Premier lieutenant |

First Lieutenant /

Fireworks lieutenant |

Deputy of the captain, platoon leader, control of the practical service and the NCOs. |

| Captains and captains | |||

| Captain / Captain | Rittmeister | Captain / Captain | Company commander or battery commander |

| Staff officers | |||

| major | major | major | Battalion commander |

| Lieutenant colonel | Lieutenant colonel | Lieutenant colonel | Representative of the regimental commander |

| Colonel | Colonel | Colonel | Commander of a regiment |

| Generals | |||

| Major general | Major general | Major general | Leader of an association consisting of three to six tactical units, brigade commander. |

| Lieutenant General | Lieutenant General | Lieutenant General | Commander of a wing or a division, entitled to be addressed as " Excellence ". |

| General of the Infantry | General of the cavalry | General of the artillery | Commander of a meeting (part of an army set up in battle order, usually two meetings in one battle) or commanding general of an army corps (largest military association in peacetime). With the right to be addressed as " Excellence ". |

| Colonel General | Colonel General | Colonel General | Since 1854, Colonel General was the designation of the highest regularly achievable rank of general in the Prussian army. Commander-in-chief of an army (during war) or inspector of an army inspection (during peace). With the right to be addressed as " Excellence ". |

| Colonel General (with the rank of General Field Marshal) | Colonel General (with the rank of General Field Marshal) | Colonel General (with the rank of General Field Marshal) | Since 1911, honorary award. Replaced the title of "characterized field marshal" previously awarded. With the right to be addressed as " Excellence ". |

| Field Marshal General | Field Marshal General | Field Marshal General | Title for special merits, e.g. B. a won battle, a stormed fortress or a successful campaign. With the right to be addressed as " Excellence ". |

Rank badge

Teams

The private wore an award button on each side of the collar, the so-called private button. The corporal corporal wore the larger badge button of the sergeants and sergeants on each side of their collar, as well as the saber tassels of the NCOs.

NCOs without portepee

Gold or silver braid on the collar and the lapels of the tunic. Saber tassel or thong with a tassel mixed in the national color.

The sergeants wore a large award button.

NCOs with portepee

Uniform like sergeants. Sergeants or sergeants and vice sergeants or vice sergeants wore the officers' side rifle (e.g. sword, saber, etc.) with portepee, sergeants or sergeants also carried a second metal braid over the cuffs ("piston rings").

Officer deputy

They wore the badges of the vice sergeants or vice sergeants with the officers' buckle belts and the epaulettes have a button-colored braid edging.

Sergeant Lieutenant

wore the uniform of the vice sergeants or vice sergeants, but also the shoulder boards of the lieutenant.

Lieutenant and first lieutenant

wore shoulder pieces (armpit pieces) made of several silver strings lying next to each other. These were interwoven with thin threads in the national colors (Prussia: black, Bavaria: blue, Saxony: green, Württemberg: black-red, Hesse: red, Mecklenburg: blue-yellow-red etc.). The numbers or names that the teams also wore were stamped on it from metal. Lieutenant without a star, first lieutenant a gold star below the numbers / names. In most cases, the epaulette fields and the shoulder pieces (advances) were the same color as the teams' epaulets. The moons of the epaulettes in button color. No fringes.

Captains or Rittmeister

Like first lieutenant, but two stars. One above and one below the numbers / names on the shoulder pieces. On the epaulettes to the left and right of it.

Staff officers

Braided silver cords with national colors. Major without a star, Lieutenant Colonel a gold star below, Colonel a gold star below and above the numbers / names. On the epaulettes, however, to the left and right of it. Epaulets with silver fringes, otherwise like lieutenants and captains.

Generals

Oak leaf embroidery on the collar and lapels. Shoulder pieces: Braided golden round cords with a silver edging cord in between. This is interwoven with thin threads in the national colors. Major General without a star, Lieutenant General one star (center), General of the Infantry / Cavalry / Artillery two stars (one above the other), Colonel General three stars (below two next to each other, above one), Colonel General with the rank of General Field Marshal four stars (two next to each other above and below) and the General Field Marshal two crossed command staffs (on edge). The stars of rank and command staffs were silver on the shoulder boards and gold on the epaulets.

Epaulettes: The rank stars of the general of the infantry etc. lay next to each other. With the Colonel General they were arranged in a triangle. In the case of the Colonel General with the rank of General Field Marshal, they were distributed trapezoidally. The field marshal's command staffs lay across the epaulette field. The moons were silver, as were the fields. Thick stiff silver cantilles (fringes).

Military training, everyday life and recruitment

General

Each army corps had its own replacement district, from which most of the personnel requirements were covered. From today's perspective, general conscription was an important integration factor in the rapidly modernizing German Empire. With around 200,000 to 300,000 men drafted annually, not all of the conscripts were drawn; Land recruits were clearly preferred. The confiscation rate of “city dwellers” or workers, on the other hand, was significantly lower. The young men experienced an organization of strict discipline that sought to practice justice. The requirements and conditions of the service were generally harsh. Abuses and attacks against conscripts were increasingly picked up by the press and sometimes even discussed in the Reichstag . The upper management felt compelled to counteract the worst undesirable developments. Service in the army became much more attractive in the course of the 19th century, and in 1912 64,000 men volunteered.

The bulk of the NCOs emerged from the ranks of the surrenders - conscripts who had voluntarily extended their two-year military service by one year. A promotion to officer was as good as impossible. Most of them served twelve years and were then placed as so-called " military candidates " primarily in the entire lower civil administration, with the post office and railroad, etc.

When it came to the next generation of officers, it was increasingly necessary to fall back on the non-aristocratic population. The prerequisite for officer applicants in Prussia was primary school , in Bavaria the Abitur , but before the First World War two thirds of the officer applicants had already had the Abitur. In 1913 70 percent of the officers were commoners.

The officer corps held an outstanding social position, especially in Prussia, less so in the southern German states. In Prussia the lieutenant was already acceptable , in Bavaria it was only the staff officer . The officer's reputation was high, for example because of the great importance of the unification of Germany, which was won by the military. Accordingly, a reserve officer career was very popular in bourgeois circles .

Wilhelm II had emphatically emphasized that the reserve officers should only be taken from the so-called "officer-capable layers". Jews were excluded because of an unwritten law. They were only able to become reserve officers in the Bavarian Army.

Every officer was obliged to uphold and defend their honor. It was not just personal and individual, but the common property of the entire corps. The class honor included loyalty to the monarch and people and fatherland , the "Prussian" sense of duty under the umbrella term of "service", but also loyalty to the bottom, a personal duty of care for his subordinates. This concept of honor led to a homogeneous officer corps with uniform norms and values.

Conscription

Every German - provided that they were fit and not excluded because of dishonorable punishments - was required to do military service from the age of 17 to 45 . Every conscript could be called upon to serve in the army or the navy between the ages of 20 and 39 .

The compulsory service was divided into:

- active service

- the reserve requirement

- the military service

- the replacement reserve obligation.

Anyone who did not belong to any of these categories belonged to the Landsturm .

Since 1893, active duty was two years for the infantry and all other infantry, three years for the cavalry and mounted artillery , one or two years for the train and three years for the navy .

Young men who were able to prove a scientific qualification (e.g. certificate after attending the lower secondary school for one year, school-leaving certificate) or who had passed the one-year examination, and who were financially able to dress themselves, could do their service as so-called one-year volunteers . They had to volunteer between the ages of 17 and 23. The examination covered three languages (German and two foreign languages) as well as geography, history, literature, mathematics, physics and chemistry. The appointment took place on October 1st of each year, exceptionally on April 1st of each year. The one-year-old volunteers were allowed - if possible - to choose the troop themselves and served for one year. After six months of active service, they could be promoted to private. The one-year volunteers were trained as officers of the reserve and the Landwehr , if they were suitable , otherwise as NCOs of the Reserve and Landwehr.

Those discharged from active duty transferred to the reserve. The reserve obligation lasted until seven years were reached together with the active duty. Reservists were required to participate in exercises lasting eight weeks.

In the Landwehr there was the first and the second contingent. After the reserve period, the first squad was transferred. For up to two years of active service, the service obligation lasted five years. Men with at least three years of active service only stayed three years in the first lineup. The men of the first contingent could be used for exercises. Landwehr soldiers belonged to the second contingent until March 31 of the year in which they turned 39. For those who started their service before the age of 20, their compulsory service ended earlier.

Men who had been adequately mustered but not called up for active military service were referred to the replacement reserve as needed. These teams were intended to supplement the army in the event of war. The group of people was very extensive, because in 1914 almost half of all those who were fit were not called up for active service. The obligation to replace reserves lasted for twelve years, from 20 to 32 years of age.

All persons between the ages of 17 and 45 who did not belong to the above groups and who were worthy or capable of military service belonged to the Landsturm. In addition, the members of the Landwehr were transferred to the Landsturm after they reached the age of 39 and the inexperienced reserve reservists after the age of 32. It was regulated according to paragraphs 14 and 20 of the German Defense Code of November 22, 1888. There were no exercises in peacetime.

Each army corps had its own replacement district, from which the troops belonging to the corps were primarily supplemented. The corps districts were further subdivided into Landwehr districts, led by a district command. The Landwehr districts, in turn, consisted of several lower administrative districts (Prussian districts, Bavarian district offices, Saxon authorities, etc.). In addition, registration offices and main registration offices were set up to monitor the conscripts. The Guard Corps did not have its own corps district, the selected replacement team of the Prussian Guard came from all over Prussia and the other federal states of northern and central Germany.

Military service began in October each year. The swearing-in took place after the war articles had been read out and prepared by clergy, denominationally in the churches and synagogues , with the hand on the flag or with the artillery on the cannon. Each state had its own formula of the oath. The swearing-in took place on the respective sovereign and the emperor. Alsatians and Lorrainers were only sworn in on the emperor. If conscripts did their military service in another federal state, they took the oath of their own state with instruction that they should also be obliged to the sovereign of their unit.

There was the option of volunteering for two, three or four years of active service - with the advantage of being able to choose the preferred type of weapon instead of being assigned. The military service could also be voluntarily extended, these volunteers were then called surrenders , from them the NCOs were preferably recruited.

Non-commissioned officers who resigned after twelve years of service were given a civil service certificate, which enabled them to prefer a preferred position in the civil service. In addition, those who passed received a service bonus (NCO bonus) of (1911) 1,000 marks.

Living conditions in the German army

Earnings and maintenance around 1900

The income (wages) of the crews and NCOs consisted of the wages paid every ten days in advance as well as the bread allowance, food allowance and clothing and accommodation with heating, lighting, etc. In special cases, financial compensation was paid for this. In addition, free medical treatment and medicines. Married NCOs also received free medical treatment and medicines for their families .

Some NCOs, such as B. Wallmeister and Zeugfeldwebel received a monthly salary similar to the officers .

| Rank | Salary or wages | Catering fee or service | Housing allowance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crews and NCOs - monthly wages in marks | |||

| Mean | 6.60 * | approx. 9 | Accommodation will be provided |

| Private | 8.10 | ||

| Sergeant | 21.60 | approx. 13 | |

| sergeant | 32.10 | ||

| Vice Sergeant | 41.10 | ||

| sergeant | 56.10 | ||

| Officers salary annually in marks | |||

| Equipment Sergeant (not an officer, but salaried) |

1104 to 1404 | 300 | Official residence |

| lieutenant | 900 to 1188 | 288 to 420 | 216 to 420 (unmarried lieutenants 6 table allowances ) |

| Captains and Rittmeister 2nd class | 3900 | 432 to 972 | 360 to 900 |

| Captains and Rittmeister 1st class | 5850 | ||

| Staff officers (no regimental commander) |

594 to 1314 | 540 to 1200 | |

| Staff officers (as regimental commander) |

7800 | 600 to 1500 | |

| Commanding general | 12,000 | 1188 to 2520 | Official residence with furnishings |

Living conditions of officers

The financial circumstances of the lower officer ranks were extremely meager. The lieutenants were dependent on allowances from home. Depending on the exclusivity of the regiment and the resulting lifestyle, allowances of 50 to 200 marks per month were necessary. A lieutenant couldn't live on his salary. Of course, this also ensured social selection. The would-be officers usually came from families who were able to provide financial support for their sons.

As a rule, it took around ten years to get promoted to captain, and the next promotion to major took another 15 years. Very few officers made it to the position of staff officer. Most of them left the army beforehand, which was easily possible at any time. There were no fixed commitment times.

An annual income of at least 4,000M was considered necessary for a marriage, which was only achieved by the elder captain. Before that, the officer could only marry if the bride brought enough money into the marriage. A “ marriage license” issued by the superior had to be available for the marriage . The financial situation was very important when this permit was granted, as was the bride's “befitting” origin.

It was only from the captain onwards that officers' salaries became comparable to those of higher officials.

literature

- Curt Jany : History of the Prussian Army from the 15th Century to 1914. Biblio Verlag, Osnabrück 1967.

- Hans Meier-Welcker (Ed.): Handbook on German Military History 1648–1939. (Volumes 2, 3), Munich 1979.

- Neugebauer / Ostertag: Basics of German military history. Volume 1 and 2: Work and source book. Rombachverlag, Freiburg 1993, 1st edition, ISBN 3-7930-0602-6 .

- Hein: The little book of the German Army. Lipsius & Tischer, Kiel and Leipzig 1901.

- Reprint: Weltbildverlag, Augsburg 1998, ISBN 978-3-8289-0271-8 .

- Ralf Raths : From mass storms to shock troop tactics. The German land war tactics in the mirror of service regulations and journalism 1906 to 1918. Freiburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-7930-9559-0 .

- Christian Stachelbeck : Germany's army and navy in the First World War. Oldenbourg, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-486-71299-5 .

Web links

- Wording of the constitution of the German Empire of 1871, regulations on the land army in Art. 57 ff.

- Wording of the alliance agreement with Bavaria

- Wording of the military convention with Württemberg

Footnotes

Remarks

- ↑ In this color combination only for this one regiment.

-

↑ For more illustrations seeCommons : flags and standards in the empire - collection of pictures, videos and audio files

- ↑ Teams received a daily salary of 22 pfennigs. These 22 pfennigs are also used in the popular text of the presentation march of Friedrich Wilhelm III. sung about. Soldiers of the guard received 1 pfennig guard allowance and thus came to 23 pfennigs.

- ↑ For this, a metal worker earned compared 1910 (turners, fitters, iron bender, grinder, etc.) every week between 20 and 40 M (~ 1,040 to 2,080 M per year).

Individual evidence

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German history of society. Volume 3, pp. 877 f.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society. Volume 33, pp. 873-885, 1109-1138.

- ↑ Thomas Nipperdey : German History 1866-1918. Power state before democracy. Munich 1992, pp. 230-238.

- ↑ Treaty between the North German Confederation, Baden and Hesse on the one hand, and Württemberg on the other, regarding the accession of Württemberg to the constitution of the German Confederation.

- ^ Hermann Mattutat: Youth Armed Forces and Workers' Movement. Published in 1914 in the Socialist monthly issue.

- ↑ Stephen Bungay: Moltke - Master of Modern Management. europeanfinancialreview.com of April 25, 2011, accessed January 6, 2017.

- ↑ The little book of the German army. Verlag von Lipsius & Tischler, Kiel and Leipzig 1901, p. 24 ff.

- ↑ a b Karl-Volker Neugebauer / Heiger Ostertag : Basics of German military history. Volume 2: Work and source book. Rombach-Verlag, Freiburg 1993, 1st edition, p. 212.

- ^ Hans-Dieter Götz: The German military rifles and machine guns 1871-1945 . 3. Edition. Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart, ISBN 3-87943-350-X , p. 105 .

- ^ Hans-Dieter Götz: The German military rifles and machine guns 1871-1945 . 3. Edition. Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart, ISBN 3-87943-350-X , p. 144 .

- ^ Hans-Dieter Götz: The German military rifles and machine guns 1871-1945 . 3. Edition. Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart, ISBN 3-87943-350-X , p. 149 .

- ^ Hans-Dieter Götz: The German military rifles and machine guns 1871-1945 . 3. Edition. Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart, ISBN 3-87943-350-X , p. 159 .

- ↑ Niel Grant: Weapon Volume 39 Mauser Military Rifles . Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2015, ISBN 978-1-4728-0594-2 , pp. 12 (English).

- ↑ Niel Grant: Weapon Volume 39 Mauser Military Rifles . Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2015, ISBN 978-1-4728-0594-2 , pp. 17 (English).

- ↑ Niel Grant: Weapon Volume 39 Mauser Military Rifles . Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2015, ISBN 978-1-4728-0594-2 , pp. 19 (English).

- ^ A b Karl-Volker Neugebauer : Fundamentals of German military history. Rombach-Verlag, Freiburg 1993, p. 220 ff.

- ^ Cabinet order of March 29, 1890.

- ↑ Section 14 of the Reich Military Law

- ↑ The little book of the German army. Published by Lipsius & Tischler, Kiel and Leipzig 1901, p. 124 ff.

- ^ Adolf Levenstein: The worker question with special consideration of the socio-psychological side of the modern large enterprise and the psychophysical effects on the workers. Munich 1912, pp. 68-75.

- ^ Karl-Volker Neugebauer: Fundamentals of German military history. Volume 1, Rombach-Verlag, Freiburg 1993, pp. 223-224.