Kingdom of Prussia

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Kingdom of Prussia refers to the Prussian state at the time of the rule of the Prussian kings between 1701 and 1918.

The Kingdom of Prussia emerged from the Brandenburg-Prussian areas after Elector Friedrich III. of Brandenburg had been crowned king in Prussia. It consisted of Brandenburg, which belonged to the Holy Roman Empire , and the eponymous Duchy of Prussia , which emerged from the Teutonic Order as a Polish fief . The originally Prussian areas in the east of the kingdom were henceforth called East Prussia .

In the 18th century Prussia rose to become one of the five major European powers and became the second major German power after Austria . Since the middle of the 19th century, it pushed the creation of a German nation-state forward and from 1867 it was the dominant member state of the North German Confederation . In 1871 this union was expanded to the German Empire and the King of Prussia took over the office of German Emperor . With the abdication of the last emperor and king, Wilhelm II , as a result of the November Revolution in 1918, the monarchy was abolished. The kingdom went up in the newly created Free State of Prussia .

story

The history of the Kingdom of Prussia and its Prussian states comprises two distinctive periods: the first half from 1701 to 1806, known as the period of the Old Prussian Monarchy, and the "New Prussian Monarchy" from 1807 to 1918. The years from 1806 to 1809 led to renewal All state institutions in a changed state territory, old Prussian lines of tradition and structures were dropped and a new era began. In the course of the Prussian reforms , the "New Prussian State" came into being.

Raised rank under King Friedrich I (1701–1713)

The new Prussian state

The countries of the Hohenzollern dynasty with their dominant focus in the Mark Brandenburg were a middle power by European standards in 1700 . As the Elector of Brandenburg, the Hohenzollern had held a prominent position as an imperial estate in the Holy Roman Empire since the 15th century . The empire was able to consolidate again after 1648, but the political position of the imperial princes was considerably strengthened with the Peace of Westphalia . With their location in the north-east of the empire, the ties between the Hohenzollern areas and the Kaiser were looser than in the central areas on the Rhine and in southern Germany. In the previous centuries, the Brandenburg electors, in the course of the effects of the Reformation and religious wars , in the struggle between the Unitarian imperial power and the polycentric princely power in the empire, also together with the Saxon electors, had at times formed a regional antithesis to the imperial power.

The rank, reputation and prestige of a prince were important political factors around 1700. Elector Friedrich III. Recognizing the signs of the times, aspired to the title of king . Above all, he was looking for equality of rank with the Elector of Saxony , who was also King of Poland, and with the Elector of Hanover , who was a candidate for the English throne. With the consent of Emperor Leopold I, he finally crowned himself on January 18, 1701 as Friedrich I in Königsberg as "King in Prussia". In return, the Royal Prussian Army took part in the War of the Spanish Succession against France on the side of the Emperor. During the Great Northern War , which broke out at the same time on the northeastern border , Friedrich managed to keep his country free from the clashes.

The restrictive "in Prussia" was retained because the designation "King of Prussia" would have been understood as a claim to rule over all of Prussia, including the western part of the Teutonic Order State , which has belonged to Poland since 1466 . The title “in” averted possible Polish claims to East Prussia, although it was associated with a lower status in the European diplomacy of the time. In the Hohenzollern state, the status of the individual parts of the country continued to apply , of which the Margraviate of Brandenburg followed by the province of East Prussia were the most prominent; the Duchy of Magdeburg , Western Pomerania and the Principality of Halberstadt formed the central provinces. The smaller western parts of the country were initially given a subordinate role. All authorities, state institutions and officials from then on bore the royal Prussian title, contrary to the current constitution.

The turn of the century marks the beginning of the heyday of European absolutism , in which the sovereign princes, after the secularization of church property in the 16th century, were able to significantly reduce the power of the immediate cities and the local nobility. In the course of the rise of the Hohenzollern in power, Berlin became the political center, at the expense of the once politically autonomous cities and the submissive peasants. Newly established sovereign institutions began to replace traditional class structures step by step. The greatly expanded Kurbrandenburg army gained a central role in securing power for the king.

In the eastern parts of the kingdom which had in the 17th century Gutsherrschaft of the landed gentry enforced from formerly free peasant serfs made; the western provinces were not affected, also because other industries dominated there. The population density decreased towards the east; the largest cities were Berlin and Königsberg, which with more than 10,000 inhabitants were also among the 30 largest cities in the empire.

Corruption, plague, famine and courtly splendor

The king ruled in the cabinet and the frequent, indirect government action resulted in a system of minions with ropes around the king. In addition to him, there were other influential officials at court who played a key role in shaping the government. In the 1700s it was primarily the Three Counts Cabinet that determined the actual state policy of Prussia. This created a significant amount of corruption emanating from the highest government offices. This put a considerable strain on public finances. This took place in a time of crisis when the Great Plague struck the Kingdom of Prussia from 1708 to 1714 , where many thousands of people perished. In addition, the millennium winter of 1708/09 led to a famine.

Frederick I concentrated on elaborate court keeping based on the French model. This and the general government mismanagement brought the Prussian feudal state to the brink of financial ruin. Only by leasing more Prussian soldiers to the Alliance in the War of the Spanish Succession was the king able to cover the costly expenses for the pomp at court. During his tenure, Prussia received 14 million thalers in subsidy payments from the Allies. The state budget in 1712 was around four million thalers, of which 561,000 were given exclusively to the court. The income consisted only partly of taxes. The Allies' subsidy payments depended on the course of the war, so they did not generate reliable income. During Frederick I's term of office, there was no significant increase in pure tax revenue.

Nevertheless, the king afforded himself an elaborate baroque court with the construction of new palaces ( Charlottenburg Palace , Monbijou Palace ) and hunting lodges in the outskirts of Berlin. The civilization deficit of the traditional agricultural state, perceived by other principalities, was to be made up within a few years through an ambitious courtly expansion program. The arts and crafts were particularly encouraged through increased orders. For the first time in the history of Brandenburg-Prussia, internationally important artists and architects such as Andreas Schlueter also worked in Prussia at this time. The entire court of Frederick was constantly on the move within the Berlin residence landscape. Construction projects and infrastructure measures were initiated, whereby the Margraviate of Brandenburg was more closely involved and developed from Berlin. A brilliant highlight of this time was the meeting of the Three Kings in 1709 in Caputher Castle . Here Frederick I was able to demonstrate the increased importance of the Prussian state since 1701. Due to the immigration of the Huguenots a few years earlier, there was now an educated and economically active bourgeoisie , mainly in the Berlin area , which formed the basis for the now increasing social differentiation . The demand from the Berlin court led to the establishment of new commercial branches and manufactories . The Huguenots also brought innovations to agriculture, such as tobacco growing in the Uckermark . The Berlin Residence was also considerably expanded and expanded with suburbs ( Friedrichstadt , Dorotheenstadt ). The number of inhabitants of the Prussian capital increased considerably. The establishment of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin and the newly founded University of Halle improved the higher education offer.

Internal consolidation under King Friedrich Wilhelm I (1713–1740)

Expansion of the army, reduction of culture

The son of Friedrich I, Friedrich Wilhelm I , was not fond of splendor like his father, but rather economical and practical. As a result, just coming out of his father's room in which he died, he cut the expenses for keeping the court and dismissed most of the courtiers after the funeral. Everything that served the courtly luxury was either abolished or used for other purposes. All of the king's austerity measures were aimed at building up a strong standing army , in which the king saw the basis of his internal and external power. He used 73% of the annual state income for running military costs, while the court and administration had to make do with 14%. During his tenure he built the Prussian army into one of the most powerful armies in all of Europe, which earned him the nickname “the soldier king”. In view of the size of the Prussian army in relation to the total population, 83,000 soldiers to 2.5 million inhabitants in 1740, Georg Heinrich von Berenhorst later wrote: “The Prussian monarchy always remains - not a country that has an army, but an army that has a country in which it is, as it were, only one quarters. "

Shortly after taking office, the War of the Spanish Succession ended , in which Prussian auxiliary troops fought against subsidies for years away from their own territory. Prussia had not played an independent role in the war; Despite this weak position, however, in the peace negotiations it was awarded the previously conquered areas around Geldern , Neuchâtel and Lingen from the Orange inheritance. The peace treaty of 1714 made it possible for the king to turn to the not yet ended Northern European conflict. Two years later he led the Pomeranian campaign , which lasted several months , which increased Prussia's property to include part of Swedish Western Pomerania including the Oder delta with the important port city of Stettin . A longer period of peace followed in Europe, which enabled Prussia to devote itself to internal development.

During his reign, Friedrich Wilhelm managed to finance the army, which was oversized in relation to its resources, and to keep it operational for decades. As a result of mass desertions, there was an excessive number of forced recruits in order to maintain the target manpower . With the introduction of compulsory military service , primarily affecting the lower classes , the cantonal regulations , as well as an effective administration and the integration of all social forces, including the nobility, under the goals of the king, it was possible to consolidate the Prussian military state. No further foreign policy goals were initially pursued.

Administrative reforms, manufacturing and government revenue

The state reorganization begun by Elector Friedrich Wilhelm in favor of princely power and at the expense of the estates and the autonomous cities was essentially completed by 1740 under his grandson, King Friedrich Wilhelm I. The transformation of the state superstructure took place under the influence of absolutism prevailing in Europe , which reached its peak in Prussia in the middle of the 18th century. In particular, King Friedrich Wilhelm I and his son and successor Friedrich II “ruled through” by means of individual decrees even in ancillary matters. This resulted in a highly personalized representation of Prussian history in the older historiography, up to and including the formation of legends and myths that arose around the great Prussian rulers of this epoch.

With the establishment of a general directorate , the initially purely princely administration was expanded to include general interests of the community, creating a uniform nationwide hierarchy with clear responsibilities. Class influences of the nobility were pushed back by the patriarchal leadership of Friedrich Wilhelm I. With the central administration geared towards the person of the monarch, which included a uniform royal bureaucracy , and the forced expansion of the standing army, institutions were created that united the geographically still fragmented country.

With extensive domain ownership and excise duties, the administrative bodies were given a concern for the development of agriculture that went far beyond fiscal interests. This was followed by a special reform of the royal domain management aimed at increasing yields , the annual income of which almost doubled between 1714 with 1.9 million thalers and 3.5 million thalers in 1740. A broadened taxation system with a uniform property tax, which included peasant and aristocratic estates equally, increased income. A mercantilist economic policy, the promotion of trade and industry as well as the tax reform helped to double the annual state income from 3.4 to 7 million thalers. The measures altogether led to a period of great state progress in the period from 1713 to 1740.

Foreign policy

In terms of foreign policy, the king was not always happy. His Spartan conception of representation differed considerably from the dominant French conception of culture. The Prussian king was decried as a sergeant at foreign courts . In courtly intrigues, the opinion was widespread that one could "lead the king around like a dancing bear on the diplomatic floor". Overall, the king was "imperial" loyal throughout the time. Dynastic ties existed with Hanover , which in turn was dynastically linked to Great Britain. The conflict with the heir to the throne, culminating in Frederick II's attempted escape in 1730, turned into a diplomatic scandal. Friedrich Wilhelm I conducted a lively diplomacy with Saxony; Alternating between competition and cooperation, there were several important state visits, trade agreements or the Zeithainer Lustlager . Significant alliance agreements were concluded with Russia, most of which were directed against Poland.

Halle Pietism, social discipline, peuplication

As the influence of the Protestant Church waned, the state, which was actively formed under Friedrich Wilhelm I, took on more and more social tasks with the help of an ethical civil service, including social reform , poor welfare and education. During his reign, the pious king promoted Halle Pietism , which became the state-determining intellectual basis in Prussia, which, according to the thesis of the historian Gerhard Oestreich, should achieve social discipline or "fundamental discipline". Developed by the means of the 18th century, characteristic of Prussia man image with extended beatings implemented social discipline spread to Europe on State reform programs. The formation of the population was the long-term goal of a state-controlled economic policy and the building of a standing army . Thanks to a population accustomed to rules, norms, superordinate standards and duties, it was possible to create social institutions that included large parts of the state. The University of Halle became the most important school for the enlightened civil service. Reason as well as faith should find implementation in state action. A state-political "Prussian style" arose with certain legal and social notions of equality. In addition to the “law of the law”, the administration also took into account to a certain extent the “law of circumstances”, ie the socio-political effects of the law. In order to fulfill the concept of compensation, compromises in the law were also accepted. The first approaches to social policy emerged; individual institutions such as the Potsdam military orphanage or the Francke Foundations in Halle were founded. In order to attract the necessary skilled workers, compulsory schooling was introduced and economics chairs were set up at Prussian universities; they were the first of their kind in Europe. At the beginning of the reign of the soldier king in 1717 there were only 320 village schools, in 1740 there were already 1480 schools.

In the course of a massively pursued peuplication policy , he let people from all over Europe settle there; so he brought more than 17,000 Protestant Salzburg exiles and other religious refugees to the sparsely populated East Prussia .

When Friedrich Wilhelm I died in 1740, he left behind an economically and financially stable country. He had increased Prussia's area by 8,000 km² to 119,000 km², and it is his merit that the population, which in 1688 was 1.5 million inhabitants, increased to 2.4 million by 1740. A downside of his tenure, however, was the heavy militarization of life in Prussia.

Rise to a major European power under King Friedrich II. (1740–1786)

Silesian Wars

On May 31, 1740, his son Friedrich II - later also called "Friedrich the Great" - ascended the throne. Unlike his father, he thought of using the military and financial potential he had built up to expand his own power. Although the king, as crown prince, was inclined to philosophy and the fine arts, the pacifist attitude did not have a noticeable effect on his government. In the first year of his reign he had the Prussian army march into Silesia , to which the Hohenzollerns raised controversial claims. In doing so, Prussia prevailed against its southern neighbor, the Electorate of Saxony , which had also made claims on Silesia, which put a lasting strain on mutual relations . The acquisition of Silesia considerably strengthened Prussia's war economic infrastructure. In the three Silesian Wars (1740–1763) he succeeded in asserting the conquest against Austria , in the last, the Seven Years War (1756–1763), even against a coalition of Austria, France and Russia . This was the beginning of the Prussian great power position in Europe and the Prussian-Austrian dualism in the empire. As early as 1744, the county of East Friesland , with which there had been trade relations since 1683 , fell to Prussia after the Cirksena dynasty there died out.

Enlightened absolutism, socio-political reforms

The age of enlightened absolutism began with Frederick II . This was expressed in reforms and measures with which the king extended state influence to almost all areas. The torture was abolished and eased censorship. With the establishment of the general Prussian land law and the granting of complete freedom of belief, he lured further exiles into the country. In his opinion, in Prussia "everyone should be saved according to his own style". In this context, his saying also became known: “All religions are the same and good, if the people, if they profess, are honest people, and if Turks and pagans came and wanted to poop the country, we wanted to build them mosquees and churches let " . In the late years of his reign, which lasted until 1786, Frederick II, who saw himself as the “first servant of the state”, particularly promoted the development of the country. The population of the sparsely populated areas east of the Elbe, such as the Oderbruch , was at the forefront of his political agenda.

The measures following Friedrich's enlightened conception of the state led to an improved rule of law . Although the administration of justice was one of his sovereign rights as an absolute ruler, Frederick II largely renounced it for more justice. In 1781 Friedrich introduced a legislative commission to evaluate the laws he had passed. In doing so, he lifted jurisprudence and legislation out of his purely subjective sphere of power without constitutionally restricting his princely sovereign rights. In an effort to displace the previously valid religious-patriarchal conception of the state ( God's right , God with us ) in favor of a more rational state based on an immaterial social and submission contract ( Leviathan (Thomas Hobbes) ), Friedrich decided in favor of the welfare of the Society and against regulatory arbitrariness . He no longer embodied the state, but was itself just an institution in the service of the state; the civil servants had the right to preserve the rights and security within the state community.

The will of the king was nevertheless still autocratically enforced through decrees, orders, secret service instructions, ordinances or patents. The administration lacked a legal and formal system, with the consequence of frequent reorganization, disputes over competencies as well as aimlessness of official actions. The king thwarted their work by deciding over them, the administration reacted with embellished and falsified reports. The cumbersome state administration around 1750 nevertheless enabled a relatively dense intensity of rule. A modern professional civil service that worked according to the departmental principle did not yet exist; To improve this, a successfully completed university degree was introduced as a prerequisite for the recruitment of senior civil servants and civil servants. With increasing age it became more and more difficult for the king to keep the strings in hand and the bureaucracy developed increasingly self-interest, with which the personally enlightened absolutism of Frederick turned into a bureaucratic state absolutism.

Frederick II subordinated all political action to the reasons of state . This led to a state centrism, which provided for the willingness to make sacrifices and subordination of every inhabitant as obedient subject (" Dogs, do you want to live forever "). Frederick II did not envisage society as an active political force; society and the economy remained subject to his claim to power. Until 1806, the nobility dominated the management positions of the administration and the military, access to the higher ministerial bureaucracy and higher military service was closed to the bourgeoisie. In spite of this, an economic bourgeoisie developed with royal protection in the industrial and commercial centers. The feudal professional ethics to get objective was the social policy of Frederick II., Which he a social mobility prevented. Maintaining the political and social status quo became the traditional cornerstone of Prussian domestic politics . By keeping all social classes within the barriers assigned to them by the state, they used the state and its army in the sense of an expansive foreign policy. In terms of financial policy, increasing income and limiting expenditure in order to maintain the high level of military capability remained an ongoing state-political goal with high priority; the economic policy was the financial policy and defense policy subordinate.

Retablissement, War of the Bavarian Succession, Prince League and First Partition of Poland

After Prussia's high war losses - estimates assume 360,000 civilians and 180,000 fallen soldiers for the Seven Years' War - Frederick II devoted himself to rebuilding the country after 1763 as part of an overall plan whose long-term goal was to increase popular education and improve the situation of farmers and the creation of manufactories. To do this, he used mercantilist methods with state subsidies for companies as well as export and import bans and further measures for market regulation. Against great internal resistance, he introduced the French direction and leased the excise to Marcus Antonius de la Haye de Launay . He restricted the Polish grain trade on the Vistula in 1772 through an unequal trade agreement. A coin decree with currency devaluation by 33 to 50 percent brought relief to the state in 1764 with the state finances. The famine years of 1771 and 1772 passed Prussia. Prussia fought trade wars with Saxony and Austria. Hundreds of new colonist villages emerged in river plains on previously drained marshland ( Frederick's Dzian colonization ).

The picture shows the arrival of a company at the New Palace in July 1775. The six-horse carriages have passed Sanssouci Palace and continue to the New Palace. Various Württemberg and Hessian princes and princesses sit in the two 6-horse carriages. King Friedrich II can be seen on a white horse.

Background: Friedrich had many siblings and therefore also had many relatives by marriage, to whose children and grandchildren he was related as an uncle in various degrees, and who lived all over Europe. They served in his army and they also came to visit their royal relatives in Berlin and Potsdam. Once a year Friedrich invited all of these relatives to stay in Potsdam for three weeks - in the New Palace.

Prussian foreign policy remained shaped by the unstable European power system even after 1763. Crises threatened to develop into continental crises, but after 1763 Prussia as well as Austria and France were too exhausted for new armed forces. The antagonism between Austria and Prussia continued, came to a head in the War of the Bavarian Succession . The Prussian policy of its own state sovereignty towards the Reich remained decisive. With the establishment of the Fürstenbund , Frederick II acted as the protector of the empire at times. Together with Austria and Russia , Friedrich operated the partition of Poland . During the first division in 1772, Polish-Prussia , the Netzedistrikt and the Duchy of Warmia fell to Brandenburg-Prussia . The land connection between Pomerania and the Kingdom of Prussia, which was outside the territory of the Reich, was thus established, which was important for Frederick II. Now “both Prussians” were in his possession and he could call himself “King of Prussia”. Administratively, this kingdom consisted of the provinces of West Prussia and East Prussia as well as the network district.

The king enlarged his territory during his reign by 76,000 km² to 195,000 km² (1786). During this time, the population of Prussia grew from about 2.4 million to 5.629 million, despite the loss of about 500,000 people during the Seven Years' War. The number of immigrants to Prussia between 1740 and 1786 is estimated at 284,500. Despite the temporary disruption of the economy as a result of the protracted wars during his reign, the state revenue rose from 7 million thalers in 1740 to 20 million in 1786. Frederick the Great died on August 17, 1786 in Sanssouci Palace .

Hubris and Nemesis (1786–1807)

Effects of the French Revolution

With the death of Frederick II, the phase of the Prussian monarchy ended, in which the king as a political actor could independently set up his own programmatic goals, define and order them in packages of measures. Frederick II, who was constantly on inspection trips, tried to cope with the increasing number of tasks with his distinctive service ethic, from which the legend of the “king everywhere” developed. In the meantime, however, the state apparatus had grown to a size that no longer enabled it to oversee and control political affairs even at the highest level of the state. By 1800 at the latest, the kingdom had become too big and society had developed too far. His successors limited themselves in government business to a less time-consuming style of rule. The steadily enlarged substructure of the state administration now took over the problem definition and the development of solutions, which the king, as the highest authority, only had to approve.

In 1786 Friedrich's nephew, Friedrich Wilhelm II (1786–1797) became the new Prussian king. Due to his lack of skills, the monarchical system got into trouble and a court with mistresses and favorites was established . His most famous mistress was Wilhelmine Enke , whom he ennobled with the title of Countess Lichtenau. Berlin grew into a handsome residential city in the 1790s. In 1791 the Brandenburg Gate was completed by the architect Carl Gotthard Langhans . Other classical buildings followed.

The Enlightenment movement under Frederick II had led to a steadily growing society of responsible, self-confident and independent individuals, whose political sense of mission was reflected in demands for participation and critical debates in the existing media and public circles. The overthrow of the absolute monarchy in France led to fears among the German princes that the ideas of the French Revolution could also spread in their own countries with the help of the enlightened bourgeoisie . Friedrich Wilhelm II was therefore under the influence of counter-Enlightenment efforts from an early age , represented by Johann Christoph Wöllner and Johann Rudolf von Bischoffwerder . The Enlightenment Berlin Wednesday Society therefore had to meet in secret; Members included the authors of the General Land Law Carl Gottlieb Svarez and Ernst Ferdinand Klein , the editors of the Berlin monthly Gedike und Biester, the publisher Friedrich Nicolai and, as an honorary member, Moses Mendelssohn . However, people who expressed themselves in a revolutionary and derogatory manner about the Prussian government were either detained for several weeks and also expelled from 1790, while others emigrated voluntarily. In 1794 the General Land Law , which had already begun under Frederick II, was introduced for the Prussian states . Although the comprehensive body of law lost its enlightened character during the reign of Friedrich Wilhelm II, it nevertheless provided a generally applicable legal basis for all Prussian provinces.

Partition of Poland, end of dualism with Austria, peace with France

The partition policy towards Poland was continued by Friedrich Wilhelm II as well as by Russia and Austria. During the second and third partition of Poland (1793 and 1795) Prussia secured further territories as far as Warsaw. As a result of this increase in area, the population increased by 2.5 million Poles and the difficult task was to integrate them into the state. Whether this would have succeeded in the end cannot be conclusively stated, since the areas of the last two partitions of Poland were initially lost to Prussia under Napoléon's rule.

In terms of foreign policy, Prussia was primarily interested in reducing Austria's strength and influence in Germany. In the 1780s, tensions between the two great powers had intensified considerably. Prussia supported revolts against Austrian rule in Belgium and Hungary. This caused the Emperor and Austrian King Leopold II to draw closer to Prussia during the time of the French Revolution . With the Reichenbach Convention of July 27, 1790, the era of bitter Prussian-Austrian dualism, which had shaped the politics of the Holy Roman Empire since 1740, was over. From then on, both powers pursued their interests together. A first meeting between Leopold II and Friedrich Wilhelm II on August 27, 1791 resulted in the Pillnitz Declaration , thanks to the influence of the Count of Artois, who later became King Charles X of France . In it they declared their solidarity with the French monarchy and threatened military action, provided that the other European powers would agree to such a step. In addition, on February 7, 1792, a defense alliance, the Berlin Treaty , was concluded between Austria and Prussia. Revolutionary France then declared war on Austria, and thus also Prussia, on April 20, 1792. The advance of the Austro-Prussian army came to a standstill on September 20, 1792 after the unsuccessful cannonade at Valmy , so that French troops could again advance into the Rhineland. In this power-consuming first coalition war against France, Prussia finally sought a compromise. The two powers came to an agreement in the Franco-Prussian peace treaty of Basle of 1795. Prussia recognized the conquests of France on the left bank of the Rhine and achieved a north German neutrality zone extending as far as Franconia . Germany thus crossed a line of demarcation that defined the zones of influence of the three great powers France, Austria and Prussia and led to peace in the north of Germany, while the south of Germany remained a theater of war.

North German neutrality zone, dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire

The Prussian solo effort meant that the other European powers mistrusted the Prussian king, so that he was isolated in the following years. With its unilateral departure from the war coalition, Prussia showed its indifference to the fate of the empire. Austria, too weak on its own, also gave up and thus admitted the end of the Prussian-Austrian great power politics in Europe. While the Empire journalism Prussia for the informal peace with France strongly condemned, the other imperial estates remained cautious. With the Berlin treaties of August 5, 1796, Prussia came into the possession of the dioceses of Münster , Würzburg and Bamberg . For the north, the Hildesheim Congress formed a kind of counter-Reichstag; Payments from the north German imperial estates no longer went to the emperor, but to the Prussian treasury. France completed the transformation of the European state system with the business-like liquidation of the empire. On November 16, 1797, Friedrich Wilhelm II died, his son Friedrich Wilhelm III. (1797-1840) was his successor. In accordance with the personal character of the new king, the Prussian government became more vacillating, deliberate and hesitant, both internally and externally. The king still ruled in absolute form around 1800, but the state administration had taken the political initiative in many areas, while the king only reacted without being able to actively and actively shape the program.

With the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss (Reichsdeputationshauptschluss) , Prussia was able to realize the considerable gains in land and people decided in the Peace of Basel in 1802/1803 and, with secularization, absorbed the former spiritual dominions of the Hildesheim Monastery , the Paderborn Monastery ( Principality of Paderborn ), the Münster Monastery ( Hereditary Principality of Münster ). , the imperial monasteries Quedlinburg , Elten , Essen , Werden and Cappenberg as well as Electoral Mainz possessions in Thuringia ; it also received the former imperial cities of Mühlhausen , Nordhausen and Goslar .

The beginning of the 19th century completed a phase of growth and expansion lasting over a hundred years. As the original European middle power, Prussia had caught up with the top ranks by 1800. Of the five great powers of the continent that was economically, socially, technologically and militarily most advanced at the time, Prussia was still by far the smallest in terms of its economic power, its population density and even in terms of its army of 240,000 men. Around 1800, its political reputation was mainly based on symbolic factors from the glory days of the Silesian Wars. This led to misperceptions among the national competitors of the time about their real strengths.

| Rank after EW |

Country | resident | Area in km² |

Inhabitants per km² |

Army size | State income in guilders |

State income in guilders per capita |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (European) Russian Empire | 36,385,000 | 4,356,336 | 8.4 | 510,000 | 110,000,000 | 3 |

| 2 | First empire | 32,359,000 | 642.365 | 50.4 | 600,949 | 252,300,000 | 8th |

| 3 | Empire of Austria | 25,588,000 | 670.513 | 38.2 | 356,000 | 120,000,000 | 5 |

| 4th | United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland | 15,024,000 | 315.093 | 47.7 | 200,000 | 260,000,000 | 17th |

| 5 | (European) Ottoman Empire | 11,040,000 | 670.208 | 16.5 | 100,000 | 54,000,000 | 5 |

| 6th | Spain | 10,730,000 | 506.996 | 21.2 | 76,000 | 75,000,000 | 7th |

| 7th | Kingdom of Prussia | 9,851,000 | 316.287 | 31.1 | 240,000 | 60,000,000 | 6th |

| Europe | 182,599,000 | 9,598,225 | 19.0 | 2,549,686 | 1,173,730,000 | 6th |

Fourth coalition war with France

Prussia's fickle policy of neutrality brought about its political devaluation, especially in France. In contemporary analyzes, discourses and reports, French voices demanded that Prussia renounce claims "which could only have been owed to the genius of the great Friedrich for thirty years, but which did not match the strength of the other powers" ( Conrad Malte- Brun , 1803). Instead, France, like the other German states, should submit as an ally, without expecting a special position.

The superiority of the French army posed a new and existential threat. Napoleon I was also unwilling to limit French expansion and therefore ignored international treaties and agreements. As a result, the Prussian government faced an acid test. In 1806, after a number of provocations, Prussia made the fatal mistake of competing militarily with France without first ensuring the support of the other great powers. In the battle of Jena and Auerstedt , the kingdom suffered a crushing defeat against Napoleon's troops. King Friedrich Wilhelm III. and his family had to flee temporarily to Memel , and the so-called " French era " began for Prussia . In the Peace of Tilsit in 1807 about half of its national territory, including all areas west of the Elbe and the land gains from the second and third partition of Poland, which now fell to the new Duchy of Warsaw established by Napoléon .

State reforms and wars of liberation (1807-1815)

The political doctrine of Christian Wolff ( Wolffianism ) was in the late 18th century by Immanuel Kant in his political theory developed designs; for a good coexistence of the people of the state the basis of all law should be the freedom of the individual. In doing so, he was based on the ideas of Adam Smith , Rousseau and Montesquieu, and especially on the idea of the separation of powers and the Volonté générale . The experience of the American and French Revolutions nurtured ideals that were incompatible with the existing political conditions of an insistent absolute monarchy. The need for reform was great after the death of Frederick II, but the reform approaches initially remained timid and limited. These ideas were decisive for the implementation of later reforms, but first a total collapse of the existing political system was necessary.

In 1807 Prussia had to endure the French occupation, supply the foreign troops and make large contributions to France. These restrictive peace conditions in turn brought about his state-political renewal with the aim of preparing the basis for the liberation struggle. With the Stein-Hardenberg reforms under the leadership of Freiherr vom Stein , Scharnhorst and Hardenberg , the educational system was redesigned, the serfdom of the peasants was abolished and in 1808 the self-government of the cities and in 1810 the freedom of trade were introduced. The army reform was completed in 1813 with the introduction of general conscription .

After the defeat of the "Grande Army" in Russia, the armistice was signed on December 30, 1812 near Tauroggen by the Prussian Lieutenant General Graf Yorck and for the Russian Empire by General Hans von Diebitsch . In the Tauroggen Convention , which York initially agreed on its own initiative without the participation of the King, it was decided to separate the Prussian troops from the alliance with the French army; that was the beginning of the uprising against French rule. At the beginning of February 1813, the entire province of East Prussia had been withdrawn from the Prussian king's grasp, and the authority was exercised by Freiherr vom Stein as the representative of the Russian government. In this situation, the Berlin government slowly distanced itself from its French alliance partner. By mid-February the rebellious mood had already spread across the Oder to the Neumark and there were the first signs of a revolution. Advisors to the king made it clear to him that the war against France would take place with him at the helm or, if necessary, without him. After a period of indecision, the king finally decided to join forces with Russia at the end of February; the Treaty of Kalisch was concluded as an anti-Napoleonic alliance and agreements were made about the future possession of territories in neighboring countries.

When the king called for the liberation struggle on March 17, 1813 with the slogan “ To my people ”, 300,000 Prussian soldiers (6 percent of the total population) were standing by due to the general conscription. Prussia became a war zone again. The main fighting along the Prussian-Saxon border zone ended for Prussia and its allies with a victory over the remnants of the French troops. After the decisive Battle of the Nations near Leipzig , in which 16,033 Prussians were killed or wounded, the end of Napoleon's supremacy over Germany was within reach. With the autumn campaign of 1813 and the winter campaign of 1814 , Napoleon's troops were further weakened. After the humiliating defeat of 1807, Prussia saw itself rehabilitated and again on a par with the Austrian Empire . Under Marshal Blücher , the Prussian troops and their allies achieved the final victory over Napoleon in the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Restoration and reaction, pre-March and March revolutions (1815–1848)

Congress of Vienna, Metternich system, German Confederation

After the end of the revolutionary era, the victorious great powers began negotiations for a stable post-war order in Europe, which led to a conservative turnaround and the establishment of the Metternich system . Friedrich Wilhelm III., The Emperor of Russia ( Alexander I ) and the Emperor of Austria ( Franz II. ) Founded the Holy Alliance ; it was supposed to suppress democratic aspirations throughout Europe and restore the absolute monarchical system.

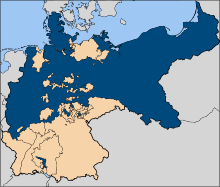

At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Prussia was given back part of its old territory. New additions were Swedish Pomerania , the northern part of the Kingdom of Saxony , the Province of Westphalia and the Rhine Province . Prussia got back the previously Polish province of Posen , but not the areas of the second and third partition of Poland , which went to Russia. Since then, Prussia has consisted of two large, but geographically separate, country blocks in East and West Germany. The newly won provinces had traditional spatial structures and ties that were no longer applicable. The term Musspreuße describes the difficult and emotionally stressful transition of the former residents to the new state. The population, primarily of the Rhine Province, brought constant unrest to the kingdom with their large and self-confident urban middle class.

In terms of power politics, Prussia was unable to assert itself at the Congress of Vienna; It could not have a decisive influence on the future structure of the German states and Saxony was preserved as a state. The Prussian delegation wanted a Germany with strong and central government functions under its own leadership. In the final act of June 8, 1815 of the German Federal Act , however, the Austrian concept prevailed. Prussia thus became a member of the German Confederation , a loose association of German states under Austrian leadership that existed from 1815 to 1866. Although Prussia had no formal authority over northern Germany , there was still enough leeway to exercise a limited de facto hegemonic position.

The new defensive foreign policy order in Europe led to a revival of fortress construction . In the new provinces in the west, mighty fortresses were built in Koblenz , Cologne and Minden , built according to the New Prussian fortification style . After 1815, Prussia remained by far the smallest of the major European powers. Strictly speaking, Prussia was neither a great power nor a small state, because of its limited scope for foreign policy, but lay between these two levels. For Prussia, this began a long phase of foreign policy passivity, during which it tried to stay out of all conflicts and to get on as well as possible with all powers. Prussia avoided a conflict with Austria. It also had largely good relations with Russia by accepting Russian hegemony over larger parts of Europe .

Conservative turn

With the murder of the theater poet and Russian envoy August von Kotzebue in Mannheim by the student Karl Ludwig Sand , the radicalism of the national unification movements became apparent. With the Karlovy Vary resolutions of August 1819, stricter censorship and surveillance measures were enacted, which were unanimously approved by the Bundestag in Frankfurt am Main on September 20, 1819 . The conservative advisors to the Huguenot Jean Pierre Frédéric Ancillon , who influenced King Friedrich Wilhelm III during the French occupation. won a wave of arrests known as the persecution of demagogues . The royal cabinet government, consisting primarily of the trio Sophie Marie von Voss , Wilhelm zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Hohenstein and Ancillon, opposed Chancellor Hardenberg, on whom the king had become dependent. Intrigue and an overall more conservative political climate in Europe led to a conservative turnaround. A poisoned political atmosphere, which suspected anyone who did not strictly follow the line, led to the dismissal of such important reformers as Humboldt , Beyme and von Boyen at the end of 1819 ; Heinrich Dietrich von Grolman and August Neidhardt von Gneisenau also went last . The promise made during the wars of freedom to give the country a constitution was canceled by Friedrich Wilhelm III. never one. In place of a central parliament as in other German states, there were only the provincial parliaments in Prussia from 1823 , which were elected and organized according to class criteria and required long-term property for the members of the parliament. Quotas initially ensured that the local nobility initially had a preponderance. Due to a structural economic crisis, the Prussian landed nobility was increasingly forced to sell real estate to the bourgeoisie. In the province of East Prussia, the share of the nobility in land ownership fell from 75.6 percent in 1806 to 48.3 percent in 1829. As a result, the provincial estates came more and more under the control of plutocrats .

The provincial estates had no legislative or fiscal powers, but were primarily advisory bodies. The conservatives had prevailed without creating any real political stability. On the one hand, the reformers had brought about lasting changes in the thinking of the political class , and the conservatives themselves had already adopted many of the reform ideas. This included the changed view of the Prussian state as an organically grown nation that included all residents . However, considerable centers of power remained with the government, especially in the areas of finance, foreign policy, education, religion and health. Ultimately, the provincial estates developed into important focal points of political change. The state parliaments increasingly sought to expand the role assigned to them and gradually increased liberal political pressure in the provinces. As political forums, they demanded that the government hold a general assembly and fulfill the constitutional promise. Their embedding in the provincial public through the provincial press and political circles of urban society, such as the Club Aachener Casino , led to the increasing spread of the state parliament debates, which were secret in themselves . This involvement of the political hinterland, which the government did not want, increased the influence of public opinion on the role of the state parliaments. With many petitions from broad sections of the population, the Berlin government demanded extended decision-making rights.

Zollverein

Due to the division of its national territory into two parts, the economic unification of Germany was in Prussia's own interest. The efforts of the royal government to combat liberalism , democracy and the idea of the unification of Germany were thus opposed by strong economic constraints. Economic deregulation and tariff harmonization were resolved in the Customs Act of May 26, 1818; the first homogeneous and nationwide customs system was created. With the establishment of the German Customs Union in 1834 under Prussian patronage, harmonization beyond Prussia's borders was achieved. This means that more and more supporters outside the country are betting on German unification; Protestants in particular hoped that Prussia would replace Austria as the leading power of the German Confederation. However, the government did not want to hear about “Prussia's German mission” for the political unification of Germany and still opposed the growing calls for a constitution and a parliament even in their own country.

Pre-march

The phase of the so-called Vormärz , which began in France in 1830 with the overthrow of the Bourbon King Charles X and destroyed Metternich's foreign policy system of restoration, became more noticeable in Prussia from 1840 onwards. The restoration policy had not been able to suppress the dynamic forces of the bourgeois movement and political progress in the long term. In the 1830s, the ruling conservative forces in Prussia were still strong enough to suppress the liberal forces that flared up here and there and thus prevent their importance from increasing. Collective protests and outbursts of resentment against the state control remained short-lived phenomena and subsided again after their suppression without any noteworthy political consequences. Protests such as the Berlin tailor revolution from 16.-20. September 1830, as well as tumults in Cologne, Elberfeld, Jülich and Aachen. In the east, too, Prussia was indirectly hit by a wave of revolution. In the Polish province of Poznan , the uprising movement from Congress Poland had to be prevented from spreading. With a policy of Germanization, the attempt was made to master the wave of enthusiasm triggered by the Polish uprising of 1830 , as a result of which thousands of Poznan people crossed the border to fight for the Polish nation.

The small and medium-sized German states were more severely affected by the July Revolution of 1830, which originated in France . In four states, social protests forced the transition to more modern constitutional forms. The unconstitutional Great Powers Prussia and Austria, on the other hand, prepared new repression measures in secret talks, which were decided in 1832 by the Federal Assembly for the German Confederation.

The aging King Friedrich Wilhelm III. died on June 7, 1840, the new King Friedrich Wilhelm IV was hopefully awaited by the liberal forces. One of the innovations associated with the change of government was the easing of censorship decreed in December 1841. An exuberant political journalism followed, so that in February 1843 new censorship regulations were introduced. With the cabinet order of October 4, 1840, the new king, like his predecessor in 1815, expressly distanced himself from the constitutional promise made.

Conflict over the United State Parliament

The hopes that the accession of Friedrich Wilhelm IV. (1840–1861) had initially aroused among liberals and supporters of German unification were soon disappointed. Even the new king made no secret of his aversion to a constitution and an all-Prussian state parliament. For the necessary approval of the funds for the construction of the eastern railway , which the military had demanded , the king had a committee of estates meet, to which representatives of all provincial parliaments belonged. When this committee declared that it was not responsible and because of increasing public pressure, Friedrich Wilhelm IV finally found himself ready in the spring of 1847 to convene a united state parliament that had long been called for.

In his opening speech, the king made it unmistakably clear that he saw the state parliament only as an instrument for granting money and that, in principle, he did not want any constitutional issues discussed; he would not allow " a written leaf to penetrate between our Lord God in heaven and this land, as it were as a second providence ". Since the majority of the state parliament demanded not only the budget approval right from the beginning, but also parliamentary control of the state finances and a constitution, the body was dissolved again after a short time. This revealed a constitutional conflict that ultimately culminated in the March Revolution .

German Revolution of 1848/1849

After the popular uprisings in southwest Germany, the revolution finally reached Berlin on March 18, 1848. Friedrich Wilhelm IV., Who initially had the rebels shot, had the troops withdrawn from the city and now seemed to bow to the demands of the revolutionaries. The united state parliament met again to decide to convene a Prussian national assembly . At the same time as the elections for the Prussian national assembly took place, which was to meet in Frankfurt am Main .

The Prussian National Assembly was given the task of working out a constitution together with the Crown. However, the assembly, in which there were less moderate forces than in the United State Parliament, did not approve the government draft for a constitution, but worked out its own draft with the " Charte Waldeck ". The counter-revolution decreed by the king after apparent concessions ultimately led to the dissolution of the National Assembly and the introduction of an imposed Prussian constitution of 1848/1850 . This retained some points on the chart , but on the other hand restored central prerogatives of the crown. A state parliament consisting of two chambers for all of Prussia was created. Above all, the right to vote in three classes had a decisive influence on the political culture of Prussia until 1918. The Austrian counterpart to the imposed constitution of Prussia was the short-lived March constitution imposed by Emperor Franz Joseph I in 1849 , which was abolished with the New Year's Eve patent of 1851.

The Frankfurt National Assembly initially assumed a greater German solution : that part of Austria that had already belonged to the Federation should naturally belong to the emerging German Reich . However, since Austria was not prepared to set up a separate administration and constitution in its non-German parts of the country, the so-called small German solution was finally decided. H. an agreement under Prussia's leadership. However, democracy and German unity failed in April 1849 when Friedrich Wilhelm IV rejected the imperial crown offered to him by the National Assembly. The revolution was finally put down in southwest Germany with the help of Prussian troops.

After Prussia's failed policy of founding a more conservative but constitutional nation- state with the Erfurt Union (1849/1850) , Austria forced the restoration of pre-revolutionary conditions in the German Confederation in the Olomouc punctuation . During the era of reaction that followed , Prussia worked closely with Austria to fight the liberal and national movement, and especially the Democrats.

As a constitutional monarchy until the founding of the empire (1849–1871)

From the Reaction Era to the New Era

Industrialization brought about a restructuring of the social classes. The population in Prussia grew rapidly. In the structure of the workforce, the factory proletariat grew even faster, triggered by the rural exodus. The urban proletariat usually lived on the subsistence level. A new social class emerged, which, driven by its predicament, from then on pushed itself into the foreground politically. The railway boosted mining and metallurgy in the Ruhr to.

The value system of pre-March liberalism lost its importance after the failed revolution of 1848. Although the bourgeoisie was denied a political say, it was still able to work in the economy. Through the accumulation of capital and means of production, the most capable among them achieved comparable top social positions in the nobility. The emergence of economic classes and class antagonisms was followed by the break in the unity of education and property. The bourgeois groups, who until then had upheld the idea of the rule of law and freedom, paralyzed in their struggle for a just liberal order. In the property elite, interest in comprehensive political reforms waned the more their economic and social position became stronger. After the experiences of the 1848 revolution, the educated bourgeois elite had also wavered in their belief in the possibilities of political impact. The working class , in competition with the bourgeois institutions, took over part of the progressive program for its own, newly forming labor movement . The latter was not ready to fight as an auxiliary force for a German nation-state dominated by education and property, the opposition movement against the state regime was henceforth divided. Only the idea of German unity had retained its luster for the bourgeoisie, despite all disappointments. Political developments in the 1850s and 1860s gave the bourgeois national movement a powerful boost.

Wilhelm I , who had already taken over the reign of his brother Friedrich Wilhelm IV, who was unable to govern after several strokes , took over the title of king in 1861 and established a phase of the "New Era"; that seemed to be the end of the time for political reaction. With War Minister Roon , he sought an army reform that provided for longer periods of service and an arming of the Prussian army . However, the liberal majority in the Prussian state parliament , which had budget rights , did not want to approve the necessary funds. A constitutional conflict arose , in the course of which the king considered abdicating. As a last resort, he decided in 1862 to appoint Otto von Bismarck as Prime Minister. He was a vehement supporter of the royal claim to sole power and ruled for years against the constitution and parliament and without a statutory budget. The liberal parliament and also Bismarck mutually made several proposals for compromise, but both rejected them again and again. So it happened that in 1866, after winning the war against Austria, Bismarck presented the indemnity law as a declaration of indemnity , in which the unapproved budgets were subsequently approved.

Assuming that the Prussian crown could only gain popular support if it took the lead in the German unification movement, Bismarck led Prussia in three wars that brought King Wilhelm the German imperial crown.

First war of unification: German-Danish war

The King of Denmark was in personal union the duke of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein , about which it is stated in the Treaty of Ripen in 1460 that these should remain “op forever ungedeelt” (“forever undivided”). Although it several times in a row to land divisions came within the duchies, the German National Liberals appealed in the 19th century on this very statement of the Ripener contract to their call for a connection Schleswig to Holstein and the German federal government to justify. Under constitutional law, only the Duchy of Holstein belonged to the German Confederation as a former Roman-German fiefdom , while Schleswig was a Danish fiefdom (see also: Danish State as a whole ). The decision of the Copenhagen government after the rejection of the previous general state constitution by the German Confederation to pass a constitution for Schleswig and Denmark alone with the November constitution led in December 1863 to a federal execution against the national Holstein and from February 1864 to protests from the Germans Confederation for the German-Danish War and the occupation of Schleswig and large parts of North Jutland by Prussia and Austria. After the Austro-Prussian victory, the Danish crown had to renounce the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg in the Peace of Vienna . The duchies were initially administered jointly in a Prussian-Austrian condominium . After the Gastein Convention of 1865, Schleswig fell under Prussian administration, Holstein initially under Austrian administration, while Austria sold its rights to the Duchy of Lauenburg to the Prussian crown. In 1866 Schleswig, the previously annexed Holstein and Lauenburg were united to form the new Prussian province of Schleswig-Holstein .

Second war of unification: war against Austria

Soon after the end of the war with Denmark, a dispute broke out between Austria and Prussia over the administration and the future of Schleswig-Holstein. Its deeper cause, however, was the struggle for supremacy in the German Confederation. Bismarck succeeded in persuading King Wilhelm, who had long hesitated for reasons of loyalty to Austria, to find a martial solution. Prussia had previously concluded a secret military alliance with the Kingdom of Sardinia- Piedmont, including Provided for the assignment of territory to Austria. Austria, in turn, had assured France in a secret treaty that it would establish a “Rhine State” at the expense of Prussia. These were clear violations of the law, since the federal act of 1815 members of the German Confederation forbade them to enter into alliances against other member states.

After the Prussian invasion of the standing under Austrian administration Holstein Frankfurt decided Bundestag , the Federal execution against Prussia. Prussia, for its part, declared the German Confederation extinct and occupied the kingdoms of Saxony and Hanover as well as the Electorate of Hesse . On the side of Austria stood the other German kingdoms and other, especially south-west and central German states. The Free City of Frankfurt as the seat of the Bundestag leaned towards the Austrian side, but was officially neutral. On the part of Prussia, in addition to some small northern German and Thuringian states, the Kingdom of Italy also entered the war (→ Battle of Custozza and Sea Battle of Lissa ).

In the German War , Prussia's army under General Helmuth von Moltke won the decisive victory in the Battle of Königgrätz on July 3, 1866 . With the Peace of Prague on August 23, 1866, the German Confederation, which in fact had already disintegrated as a result of the war, was also formally dissolved and Austria had to withdraw from German politics. Through the annexations of the opposing states Kingdom of Hanover , the Electorate of Hesse , Duchy of Nassau and the Free City of Frankfurt , Prussia was able to connect almost all of its territories with one another. It formed the provinces of Hanover , Hessen-Nassau and Schleswig-Holstein from the territories gained .

Five days before the peace agreement, Prussia had founded the North German Confederation together with the states north of the Main Line . Initially a military alliance, the contracting parties gave it a constitution in 1867, which made it a federal state dominated by Prussia, but which did justice to federalism in Germany . The constitution drafted by Bismarck anticipated that of the German Empire in essential points . The King of Prussia was the holder of the Federal Presidium and appointed the Prussian Prime Minister Bismarck as Federal Chancellor. The southern German states remained outside the North German Confederation, but entered into “ protective and defensive alliances ” with Prussia.

Bismarck's increased popularity as a result of his military success had prompted Bismarck, in the run-up to the founding of the North German Confederation, to subsequently request the Prussian state parliament to grant him impunity for the budget-free period of government. The acceptance of this indemnity bill led to the division of liberalism into a part that belongs to the authorities ( National Liberal Party ) and a part that continues to be opposition ( German Progressive Party as a rump party). The German Customs Parliament established in 1867 by Bismarck's tough conduct of negotiations and under pressure from the economy brought about the inclusion of South German representatives in an institution dominated by Prussia and North Germany. Majority resolutions replaced the veto rights of the individual states that had previously existed in the German Customs Union. Bavarian and Württemberg patriots reacted with just as much concern as the French Emperor Napoléon III. However, when the latter demanded a territorial equalization in return for France's policy of standstill towards Prussia, he inadvertently stirred up public distrust in the southern German states. This in turn strengthened their ties to Prussia.

Third War of Unification: Franco-German War

With vague promises that Luxembourg might be left to France , Bismarck had Napoléon III. made to condone his policy towards Austria. Now France was faced with a strengthened Prussia, which no longer wanted to have anything to do with the earlier territorial commitments. Relations between the two countries deteriorated noticeably. Finally, in the Emser Depesche affair , Bismarck deliberately intensified the dispute over the Spanish candidacy for the throne of the Catholic Hohenzollern Prince Leopold von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen to such an extent that the French government declared war on Prussia. This represented an alliance case for the southern German states of Bavaria , Württemberg , Baden and Hesse-Darmstadt, which is still independent south of the Main line .

After the rapid German victory in the Franco-Prussian War and the ensuing national enthusiasm throughout Germany, the southern German princes now also felt compelled to join the North German Confederation. Bismarck bought King Ludwig II of Bavaria with money from the so-called Welfenfonds from the willingness to propose the German imperial crown to King Wilhelm. The German Reich was founded as a small German, unified nation- state , which was already envisaged as a model of unification by the National Assembly in 1848/49. In the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles , Wilhelm I was proclaimed German Emperor on January 18, 1871 - the 170th anniversary of Frederick I's coronation .

As a federal state in the German Empire (1871-1918)

Imperial Constitution

With the establishment of the Reich, the individual German states ceased to be subjects of international law and sovereign members of the European state system. They were now represented within the international society by the German Reich. As recently as 1848, the Prussian elite were self-sufficient and opposed to the national movement . At the time of the founding of the empire, Prussian particularism no longer emerged so clearly. However, there remained fears on the part of the ruling class that Prussia would withdraw completely behind the Reich.

From 1871 on, Prussia was just as much a part of the German Empire as the German Empire assumed a Prussian character. Prussia's leadership role was constitutionally anchored in Article 11, which granted the King of Prussia the presidium of the empire with the title of German Emperor . The personal union of king and emperor also resulted in the personal union of the offices of Prussian Prime Minister and Imperial Chancellor , although this was not prescribed in the constitution. The Prime Minister and Chancellor did not necessarily have to be Prussian, as the appointment of Clovis as Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst shows. There were a total of three such short interruptions, none of which worked. The Reich Chancellor needed the backing of power for Reich policy that the chairmanship of the Prussian State Ministry gave him. The designation "German Kaiser" and not "Kaiser von Deutschland" meant that the title of emperor was inferior in hierarchical terms. This created title was intended as primus inter pares in relation to the other sovereigns in the empire . A direct rule of the Prussian king as German emperor over non-Prussian territory was constitutionally not possible.

The Prussian hegemony in the Reich was based on his real power in Germany. About 2/3 of the state area was Prussian territory. About 60 percent of the population were Prussian citizens. Prussia, with its tried and tested army, was the military supremacy. Of the 36 existing divisions of the Imperial Army in 1871, 25 were Prussian. Prussia was also Germany's economic supremacy. It had the largest industry in Germany and the most deposits of usable minerals. The brown coal and hard coal deposits were also almost exclusively on Prussian territory. The large fertile agricultural areas were also on Prussian territory.

The drafting of imperial bills and the fulfillment of other imperial tasks by Prussian ministers and authorities meant that the empire was initially ruled and administered by Prussia. This superiority was reinforced by the fact that in the first few years the Reich had only a few authorities of its own and had to fall back on the Prussian authorities for the conduct of official business. In order to guarantee the constitutional tasks of the Reich, Prussia handed over several ministries and other central authorities to the Reich in the 1870s. This included the Foreign Office, the Central Bank of Prussia , the General Post Office , and the Ministry of the Navy .

As a result of this staggered transfer of institutions from Prussia to the Reich, the image of Prussian dominance changed over time. This was also structurally promoted by the Clausula antiborussica . On the one hand, Prussia received only 17 out of 58 votes in the Bundesrat, the central federal state organ of the Reich. This meant that it could be overruled by the other German states when it came to resolutions, even if this only seldom happened. In return, Prussia had the right to veto changes to the military constitution, customs laws and the imperial constitution (Articles 5, 35, 37 and 78 of the imperial constitution).

Overall, the imperial authorities emancipated themselves from Prussia and the previous relationship between Prussia and the Reich was reversed. The state secretaries of the Reich offices now pushed into the top Prussian offices. The interests of imperial politics thus took precedence over the interests of Prussia.

Foreign policy, domestic policy

The foreign policy of the new Reich was carried out in Berlin, largely by Prussian personnel under the direction of Prussia's Foreign Minister Bismarck, who was also Chancellor of the Reich. The foreign policy continuities of Prussian foreign policy were preserved even after the state was founded. The German Empire, which essentially represented an enlarged Prussia, was still geopolitically wedged between Russia and France and could find itself in an existential danger position due to a coalition of the two great powers. The status quo should be secured by continuing the traditional Eastern alliance with Russia. As before Prussia, the German Reich was able to navigate between the powers to prevent a broad anti-German coalition of the major European powers.

Between 1871 and 1887 Bismarck led the so-called Kulturkampf in Prussia , which was supposed to push back the influence of political Catholicism . Resistance from the Catholic population and the clergy, especially in the Rhineland and in the formerly Polish areas, forced Bismarck to end the dispute without any result. In the parts of the country where the majority of the population was inhabited by Poles, the Kulturkampf was accompanied by an attempt at a policy of Germanization. The Prussian settlement commission, for example, tried to acquire Polish land for German new settlers with limited success. After Bismarck's dismissal, the Germanization policy was continued by the German Ostmarkenverein , which was founded in Posen in 1894.

Wilhelm I was followed in March 1888 by Friedrich III, who was already seriously ill . who died after a reign of just 99 days. In June of the " Three Emperors Year " Wilhelm II ascended the throne. He dismissed Bismarck in 1890 and tried from then on, in late Byzantine fashion, to have a say in the highest politics of the country. The court and the court ceremony swelled again in all their splendor. The emperor endeavored to maintain his position and function as an important official or at least to give the impression that he, the king, would continue to be the most important figure in politics.

High industrialization

The period of high industrialization brought about a comprehensive modernization push for Prussia, at the height of which around 1910 the federal state of Prussia and the German Empire belonged to the group of the world's leading political, economic and technological states. The cities grew by leaps and bounds and Berlin developed into one of the largest metropolises in the world. The Ruhr area and the Rhineland also experienced unprecedented growth. Within a few years, pulsating cities were raised from insignificant provincial towns. In particular, the rural exodus but also the inhabitants from the eastern areas of Prussia contributed to this population growth on the Rhine and Ruhr. The demographics had the characteristics of a population explosion . Large families were the norm. In connection with this, epidemic outbreaks such as cholera but also pauperism were widespread. The start-up boom brought an economic development boost.

Innovation, a spirit of progress and top performance took place in Prussia in the decades around 1900. The scientification of the economy took place above all in the electrical industry , the chemical industry , in mechanical engineering and shipbuilding, and also in large-scale agriculture. This development started earlier and more strongly in Prussia than in the other German states. In connection with economic interests, numerous regional or local science-promoting societies, academies, foundations and associations were founded. This made Berlin, the Ruhr area, Upper Silesia and the Rhineland into globally important innovation clusters . The Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Promotion of Science was trained as a central network support company .

Imperialism and German nationalism

The ruling imperialism led to an exaggeration of self-perception, which developed megalomaniac traits and encompassed all strata of the population. Warmongering , Germanism and masculine aggression ("We Germans fear God, but nothing else in the world") acquired the character of a widespread, culturally accepted mass phenomenon in the run-up to the First World War. The Prussian-patriarchal social model and the imperious demeanor of the state elites now also imitated the men below in the hierarchy in their immediate environment at work, in their families, on the street, in the clubs. The Prussian masculinity culture (e.g. fraternities , conscripts) of this time meant that the vast majority of men wrested unnatural harshness but also heteronormative obsessions in order to outwardly adopt the socially required type of "(real) German man" are equivalent to. This in turn shaped a structural social potential for violence and promoted the militaristic attitude of most men of that time. The misrepresentation in the culture of upbringing and socialization was exemplary in Wilhelm II, who absolutely wanted to prevent his physical disability. As a result of the suppression of the individual personality and the resulting cleavage of feelings , a type of person with an authoritarian personality spread in Prussia , who then transferred these self-restricting social forms to the next generation and thus, as a “psychological basis”, contributed to the failings of German history between 1933 and 1945.

Answering the social question

At the same time, however, the standard of living of society as a whole rose significantly from 1850 to 1914 . A broader bourgeois middle class developed and the top performers of the bourgeois class made it into high society . There were thus sufficient incentives and offers for integration by the (state) elites for the representatives of the bourgeois class, so that they could come to terms with the prevailing political conditions. The character of the state elites changed from feudal aristocratic to plutocratic . This was accompanied by a change in the self-portrayal of the new elites. The de facto elite reorganization in Prussia since 1850 resulted in an increase in the control competencies of the elite class, which now included both state officials and the wealthy from the economy. To an increasing extent, softer methods of rule ( soft power ) were also used, which also changed the character of the until then rather authoritarian, fatherly state . This gained a caring, quasi maternal component, which complemented the authoritarian model of the state superstructure without displacing it. At that time, the state treated its citizens more like a parent-child relationship. The state did not regard citizens as mature and independent persons.

As a result, social innovations after 1848 no longer took place in the area of political participation and democratic co-determination, but predominantly in the social (welfare) area. The state's answer to the social question raised by the struggles of the working class led to new state welfare obligations, which were expressed in the beginning of social legislation . It was an attempt, after the bourgeois class found greater consideration in the state institutions after 1848 and thus became “agents of the monarchical system”, to bind the workers to the ruling system and to neutralize their radicalism and ideas of revolution. It emerged social and a wider network of social services. This was intended to combat grievances such as child labor , wage dumping and slum-like living conditions, which had affected around 30 to 35 percent of the population in the course of high industrialization.

The merit of the working class was to have shifted the focus of social development. Previously, this revolved among the bourgeois reformers around an elite-like debate about a hypothetical co-determination on a theoretical and abstract level, from which the mass of the people hardly benefited. The social discourse now dealt with very specific and practical issues that revolved around the satisfaction of individual basic needs (enough food, labor rights, limited working hours, security in emergencies, education, medical care, security, hygiene, living space).

The social starting point on the basis of which the development of society took place was still low around 1850. The majority of people in the 18th century were exposed to even greater hardships in their social life and legally provided with even less protection (people at the level of objects without basic rights ). In this respect, all problems and improvements already bore signs of a more advanced civilization with higher cultural standards than before.

Around 1900 there was at the same time a heterogeneous club-related social life in sport, culture, and leisure. Tourism became increasingly important. The pluralism of opinion became more and more apparent.