German Confederation

The German Confederation was a federation of states agreed upon in 1815 by the “ sovereign princes and free cities of Germany” including the Emperor of Austria and the kings of Prussia , Denmark (with regard to Holsteins ) and the Netherlands (with regard to Luxembourg ). This federation existed from 1815 to 1866 and already had federal features, since a law of the German federation developed that bound the member states . Nevertheless, the German Confederation had no state authority , but only “association competence mediated under international law ” ( Michael Kotulla ). According to the preamble to the federal act, the princes had united in a “permanent alliance”, but these are to be seen as representatives of their states. The federal government's task was to guarantee the internal and external security of the member states. The federal purpose was thus significantly more limited than that of the Holy Roman Empire , which had been dissolved in 1806. This German federation finally failed because of the different ideas about state and society, but above all because of the political power struggle between Prussia and Austria .

During the revolution of 1848/49 , the federal government lost its importance and in fact dissolved in July 1848. After the suppression of the revolution, after the interlude of a Prussian-dominated Erfurt Union and an Austrian-dominated rump federation, the federation in its entirety was not restored until the end of 1850.

The German Confederation was due to the German war in the summer of 1866 dissolved . Prussia and its allies founded a federal state , the North German Confederation . This was not formally a successor to the German Confederation, but took up many ideas and initiatives from that time. A "German Confederation" existed for a short time at the beginning of 1871. By agreement of the North German Confederation with Bavaria , Württemberg , Baden and Hesse on December 8th and resolution of the Federal Council and the Reichstag on 9/10. December 1870 the half-sentence "This union will bear the name of the German Confederation " was replaced by: "This league will bear the name of the German Empire "; the provision on the new state name came into force on January 1, 1871. With the new Reich constitution of April 16, 1871, the "German Confederation" was deleted from the title of the constitution.

Foundation of the German Confederation

The first attempts to establish a German Confederation went back to the First Peace of Paris on May 30, 1814. This contained a clause on the future of the German states. These should be independent of one another, but at the same time be linked to one another by a common federal bond. After discussing other models , the Congress of Vienna largely followed these results on June 8, 1815. The founding charter of the Federation, the German Federal Act , was part of the Vienna Congress Act . With it, the princes and the free cities of Germany decided to unite in a long-term alliance, the German Confederation , as part of a new European economic and peace order.

The federal act was initially signed by 38 representatives of the future member states , 34 principalities and four free cities; the 39th state, Hessen-Homburg, was not incorporated until 1817. Their number sank, despite the admission of further members, through associations as a result of purchase or inheritance to 35 states by 1863.

In 1815, the area of the German Confederation comprised around 630,100 square kilometers with a population of around 29.2 million inhabitants, which grew to around 47.7 million inhabitants by 1865. Belonging to the German-speaking area was not a criterion. The Austrian Emperor and the King of Prussia acceded to their " possessions previously belonging to the German Empire ", therefore only to those of their states that had been part of the Holy Roman Empire, which is why only these parts belonged to the German Confederation, for example also the Kingdom of Bohemia . Also members of the German Confederation were the King of England as King of Hanover (until 1837), the King of Denmark as Duke of Holstein and Lauenburg (until 1864) and the King of the United Netherlands (from 1830/39 of the Netherlands ) as Grand Duke of Luxembourg and Duke of Limburg (from 1839).

As the protectorate of the victorious powers of the Sixth Coalition War , after the fall of Napoleon , the German Confederation, like the so-called Holy Alliance (which, in addition to Russia , Austria and Prussia , also belonged to France from 1818 ) , sought the restoration of the Ancien Régime . On the other hand, during the revolution of 1848/49 bourgeois resistance formed, which wanted to replace the confederation of more or less autocratic monarchies with a federal state with a democratic basic order. When the federation was founded, there were states and politicians who wanted a closer federation or even a federal state. Initiatives to renew the federal government led to the protracted federal reform debate .

The European dimension of the federal government

The German Confederation was one of the central results of the Vienna Congress of 1814/15. On June 8, 1815, the assembled powers sanctioned the international legal basis of the German Confederation with the German Federal Act ; According to the Vienna Final Act , it was an "association under international law" (Art. I) and, as a subject of international law, had the right to wage war and to make peace . This was formally a constitutional treaty of the participating member states . By inserting the Federal Act into the Vienna Congress Act, the founding of the great European powers was guaranteed. At least that was the view of the major foreign powers, who thereby reserved the right to object to constitutional changes. The German states, however, strictly rejected this claim. Nor was it expressly formulated in the files.

Since the federal act was only a framework agreement, it had to be supplemented and specified. It was not until five years later that the representatives of the federal states and cities reached an agreement at the Vienna Ministerial Conference and signed the final act. It was unanimously adopted by the Federal Assembly on June 8, 1820 and thus came into force as the second federal constitution with equal rights.

At the European level, the federal government should ensure calm and balance. Last but not least, the military constitution served this purpose. As a whole, through the creation of a federal army from contingents of the member states , the federal government was able to defend itself , but structurally it was not capable of attack .

The guarantee powers were Austria, Prussia, Russia, Great Britain , Sweden , Portugal and Spain . If individual member states violated the content of the treaty, they felt they were entitled to intervene in internal federal affairs. This was the case around 1833 in connection with the Frankfurt Wachensturm , when federal troops occupied the city. This led to protests from the British and French governments, who believed this to be a violation of the guaranteed sovereignty of the individual states.

The aforementioned membership of foreign kings also included the Federation in the European community of states. Like the fact that a large part of Austria and also a significant part of Prussia outside the Federal territory was, she stood in contradiction to under the influence of nationalism emerging demand for creation of a nation-state . That is, the membership of princes of foreign states, as well as the fact that Prussia and Austria had extensive territories outside the federal government, contradicted the gradually prevailing principle of nation states.

Members of the Federation

The individual (as of September 1, 1815 a total of 41) member states of the German Confederation:

- the empire of Austria without Galicia and Lodomeria , Hungary , Croatia , Dalmatia and Lombardy-Venetia ; since 1818 the westernmost part of Galicia ( Auschwitz , Saybusch , Zator ) also belonged to the German Confederation

- the Prussian state without the Kingdom of Prussia (consisting of the provinces of East and West Prussia until 1824 ) and the Grand Duchy of Posen ; from 1848 to 1851 the province of Prussia and the west and north of the divided province of Posen were part of the covenant

- the kingdoms of Bavaria , Saxony , Hanover (until 1837 in personal union with the United Kingdom ), Württemberg

- the Electorate of Hesse-Kassel , the Grand Duchies of Baden , Hesse-Darmstadt , Luxembourg (in personal union with the Netherlands , the western part of Luxembourg left the Confederation in 1839 after unification with Belgium. The Dutch Duchy of Limburg became a federation, see below ), Mecklenburg-Schwerin , Mecklenburg-Strelitz , Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach , Oldenburg

- the duchies of Holstein and Lauenburg (until 1864 in personal union with Denmark ), Nassau , Braunschweig , Saxe-Gotha , Saxe-Coburg , Saxe-Meiningen , Saxe-Hildburghausen , Anhalt-Dessau , Anhalt-Köthen , Anhalt-Bernburg , Limburg (from 1839 ; in personal union with the Netherlands)

- the principalities of Hohenzollern-Hechingen , Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen , Liechtenstein , Lippe , Reuss older line , Reuss younger line , Schaumburg-Lippe , Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt , Schwarzburg-Sondershausen , Waldeck

- the Free Cities of Bremen , Frankfurt , Hamburg , Lübeck

- from 1817 the Landgraviate of Hessen-Homburg as a result of the belated recognition of its sovereignty

- The rule Kniphausen had a special constitutional position in relation to the German Confederation , which until 1854 had limited sovereignty, but was not a member of the Confederation.

The number of members changed several times, mainly because some ruling houses died out and their countries were united with those of their heirs:

- In 1818 the federal government took over the territory of the former Bohemian Duchy of Auschwitz-Zator in favor of Austria.

- In 1825 the house of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg died out, so that a reorganization of the Ernestine duchies became necessary. The Hildburghausen partition treaty regulated the division of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg in 1826, whereby Saxe-Gotha came to Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld , which became Saxe-Coburg-Gotha through the assignment of Saalfeld to Meiningen . Altenburg came to the Duke of Hildburghausen, who gave Hildburghausen to Saxe-Meiningen and became Duke of Saxe-Altenburg .

- In 1839, the Duchy of Limburg (a Dutch province) was added as compensation for Walloon parts of Luxembourg that were incorporated into the new Belgian state after the revolution . The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg itself (still in personal union with the Netherlands) remained in the federal government.

- In 1847, Anhalt-Köthen passed by inheritance to Anhalt-Bernburg .

- 1848-1851 came due to a Bundestag resolution Prussia eastern provinces Prussia (the kingdom ) and - subject to a regulation for the Polish population - Posen (the Grand Duchy ) to the German Confederation. Prussia had this recording reversed in 1851 in order to emphasize its status as a major power in its own right (with areas outside the federal government).

- In 1849, Hohenzollern-Hechingen and Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen abdicated to the Prussian state.

- In 1863, Anhalt-Bernburg passed by inheritance to Anhalt-Dessau , which was then only called Anhalt .

- On March 24, 1866, a few months before the end of the Confederation, Hessen-Homburg came to Hessen-Darmstadt by inheritance.

Schleswig was part of an Austro-Prussian condominium since 1864 , together with the federal members Holstein and Lauenburg. In the remaining time of the Federation, however, it no longer became a federal member.

Federal organs

The central federal body was the Federal Assembly (Bundestag), which met in Frankfurt am Main , and was a congress of ambassadors that met continuously. This met for the first time on November 5, 1816. The first task was to create a Federal Basic Law with regard to external, internal and military conditions (Art. 10 Federal Act). So it was a matter of filling out the framework of the federal act. However, this only happened in part, even though the Vienna Final Act of June 8, 1820 was an attempt to summarize federal law in a constitutional manner.

The Federal Assembly consisted of the plenary session and the “narrow council”. All states were entitled to vote as such in the plenary session. However, the number of votes was based on the number of inhabitants. A state could only cast its votes together. In addition, government representatives voted, not representatives of the people. The Federal Assembly is thus very much reminiscent of today's Federal Council of the Federal Republic of Germany .

The plenary seldom met. It was primarily responsible for questions of principle or for setting up new federal institutions. In these cases a unanimous vote was necessary. This principle blocked the structural development of the federal government. On the other hand, the Executive Council met regularly as the executive sub-organ of the Federal Assembly under the chairmanship ( Federal Presidium ) of Austria. This had 17 members. While the larger states of Prussia , Austria , Saxony , Bavaria , Hanover , Württemberg , Baden , Hessen-Kassel , Hessen-Darmstadt , the Duchies of Lauenburg and Holstein as well as the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg had so-called virile votes and thus provided their own representatives, the smaller states had only a curious voice . They were only involved in the deliberations indirectly and jointly through one of six curiae. The federal agent with voting rights changed regularly between the states. This distinction between viril and curiate voices, like other elements, was adopted by the Diet of the Old Kingdom.

A simple majority was sufficient to pass resolutions in the Select Council . In the event of a tie, the Austrian President's envoy gave the casting vote. Federal law took precedence over the law of the member states . Otherwise the respective state laws apply. Measured by the distribution of votes, neither Austria nor Prussia could outweigh the plenary session or the inner council. Neither of the two large states was able to outvote the other federal members together with the virile votes of other states.

In this respect, the structure of the federal government did not correspond to a Metternich system tailored to Austria , but initially had a fundamentally more open federal constitution and gave rise to hopes for the development of the federal government towards a nation-state among national-minded citizens . That was, of course, over with the beginning of the restoration period. In the large states of Austria and Prussia in particular, the introduction of a constitution was not implemented until the revolution of 1848 .

Even if most constitutional historians take the view that the German Confederation was just a loose confederation of states that had no other organs apart from the Bundestag , approaches to a federal order have also developed in the constitutional reality . After the Karlsbad decisions, two judicial (not police ) authorities , the Mainz Central Investigation Commission and the Federal Central Authority in Frankfurt am Main, were established. In addition, decisions on economic policy issues, the regulation of emigration and other problems were made in various committees of the Bundestag.

Some foreign states were represented in the Bundestag; With a few exceptions, however, the Federation itself did not maintain an active embassy system, although Article 50 of the Vienna Final Act expressly provided for a common foreign policy and an active and passive federal embassy law. Above all, the two major European powers had no interest in an independent foreign policy, and this would also have contradicted the principle of the sovereignty of the individual states. This remained a matter for the larger individual states. For a long time the union didn't even have its own symbol; It was not until March 1848 that the Federation adopted black, red and gold as the federal colors.

The structure of the Federal Assembly as a conference of ambassadors led to a mostly slow decision-making process. In addition, it soon became apparent in practice that the federal government was usually only able to make decisions when Austria and Prussia worked together. Especially after 1848 and after 1859, the rivalry between the two great powers flared up and eventually led to the end of the covenant.

The history of the Federation from 1814 to 1866 was thus pervaded by the juxtaposition and opposition of Austria, Prussia and the “ Third Germany ”. As long as the German great powers worked together, the German Confederation was an instrument to discipline the small and medium- sized states. This came into play, for example, when there was liberalization in the area of associations or the press. The highlights were the phases of the Restoration after 1819 and the reaction after 1849. In contrast, the smaller and medium-sized states had more in times of revolutionary unrest, such as in the July Revolution of 1830 and in the Revolution of 1848/49, as well as during the phases of the Prussian-Austrian conflict Freedom of movement. The strong position of the two great powers, however, did not arise from the construction of the Confederation, but was based essentially on power politics, which if necessary also made use of military force. Since the two German great powers extended beyond the federal government, they were able to maintain more troops than the Federal War Constitution of 1821 allowed them. This clearly distinguished them from the smaller federal states.

Nevertheless, the construction of the federal government itself contributed to the maintenance of internal peace and the territorial integrity of the member states for a considerable historical period, although not only the major German powers , but also medium- sized states such as Bavaria, Baden and Württemberg tended to acquire or annex further areas. An important factor was the delivery order (of delivery or delivery ). As a supplement to Article XI of the Federal Act, the Austrägalordnung of the German Confederation was passed on June 16, 1817. This provided for a differentiated procedure for disputes among themselves. In a first step, the Federal Assembly itself should try to find a balance. If this failed, a special Austrägal instance should be brought in. One of the highest courts of justice in a member state could be designated for this. In addition to an enforceable executive, the federal government also lacked a permanent federal court of last instance, but recourse to the courts of the federal states offered a certain substitute in particularly problematic cases. Between 1820 and 1845, Austrägal proceedings were initiated in 25 disputes, including a long-running trade dispute between Prussia and the Anhalt principalities. Despite the important role played by the federal government in maintaining peace internally, this aspect has so far been neglected by research.

Federal military violence

organization

In part, in contrast to the idea of an entity that was barely capable of acting, the German Confederation had a well-developed military order. He had a Federal War Constitution and an executive order to enforce his decisions against conflicting states.

A federal military commission carried out the ongoing organizational work on behalf of the federal assembly. But if necessary, a considerable military power could also be mobilized abroad with the armed forces. This consisted of an armed forces divided into ten army corps. Part of it even existed as a standing army. However, there was no single army, but the military was made up of contingents of members. Austria and Prussia each provided three corps , Bavaria one, and the other three corps were mixed units from the other federal states. The military contribution was based on the number of residents. Therefore the preponderance of Prussia and Austria was reflected in their shares in the federal troops. In total, after a mobilization, the federal government came to around 300,000 men.

The federal fortresses , in which the standing part of the troops were stationed, were of considerable importance . These lay along the borders with France, as there was fear in the West that new revolutionary movements or state expansionist efforts would spread. The largest fortress until 1859 was in Mainz , followed by Luxembourg and Landau and, after the Rhine crisis of 1840, Rastatt and Ulm . To maintain the fortresses, the member states paid into a federal register .

There was no permanent supreme command of the armed forces. For the individual case of war, the Federal Assembly's narrow council elected a federal general . This was responsible to the Federal Assembly. However, the corps commanders of the troops were determined by the sending states.

Federal executions and federal interventions

In 1830, for example, federal troops with a commander from the Kingdom of Hanover prevented the annexation of Luxembourg by the newly emerging Belgium . After the Frankfurt guard storm in the free city of Frankfurt, Prussian and Austrian federal troops intervened from the Mainz federal fortress in 1833. In the revolutionary year 1848/49, federal troops were used against the revolutionaries several times. Initially, this was done on the orders of the old Bundestag, for example during the April Revolution in Baden against Friedrich Hecker and Gustav Struve . In the summer of 1848, the federal troops in the fortresses passed into the command of the provisional central authority . They were used many times as imperial troops, most recently to remove the democratic Baden government in the summer of 1849 with the support of other Prussian units.

The federal intervention by federal troops, the so-called penal Bavaria , after the revolution between 1850 and 1852 in Electoral Hesse in support of the largely isolated reactionary Elector Friedrich Wilhelm was particularly spectacular .

Due to the still unsolved Schleswig-Holstein question and the constitutional conflict triggered by the Danish side, federal troops with one brigade each from Austrians, Prussians, Saxons and Hanoverians moved into Holstein, which belongs to the Danish state as well as to the German Confederation (→ federal execution against the duchies of Holstein and Lauenburg from 1863 ). In the subsequent German-Danish War , Denmark suffered a defeat in 1864 and had to cede Schleswig to Prussia and Holstein to Austria. Disputes over the future of these areas and ultimately over the supremacy in the German Confederation ultimately led to the German War of 1866, before which Austria applied for federal execution against Prussia . Prussia unilaterally declared the German Confederation dissolved and defeated the allied federal troops.

The assertiveness of the federal troops ended with the great powers Austria and Prussia; it was just strong enough to assert itself against small and medium-sized states. In some cases, the threat of federal execution was enough to induce a country to give in. That concerned z. B. the state of Baden, which in 1832 was forced to renounce a liberal press law in this way. The federal military power undoubtedly played an important role as a repressive means against the various political movements in the German states. On the other hand, the military power of the federal government and the hegemony of the great powers Prussia and Austria ensured a peace-keeping balance internally until 1866.

Interior design during the restoration period

The federal government was of considerable importance in domestic politics, in which the problematic contradictions between agricultural and industrial society, between the Protestant north and the Catholic south and between constitutional and absolute monarchies within the federal territory had to be taken into account. There were limits to what matter could be agreed. It is true that recent research emphasizes that the Federal Assembly has often debated the economic, trade and transport issues provided for in Article 19 of the Federal Act; but no decisions were made. The various customs associations came into this loophole and thus essentially took on an original federal task. The continuation of the emancipation of the Jews as provided for in the Federal Act and anchoring freedom of the press were also not implemented.

Constitutional question

Even before the founding of the Confederation, constitutions began to emerge in rather small states, before developments also reached the larger states. It all started with Nassau (1814), followed by Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt (1816), Schaumburg-Lippe (1816), Waldeck (1816), Saxony-Weimar-Eisenach (1816), then Saxony-Hildburghausen (1818), Bavaria (1818) , Baden (1818), Lippe-Detmold (1819), Württemberg (1819) and Hessen-Darmstadt (1820). Other states followed until finally Luxembourg (1841) put the final point in the constitution of the Vormärz '.

Some of the MPs already had free seats. Everywhere, however, the old class traditions continued to have an effect, such as the primacy of the nobility in the creation of a first chamber or mansion. Representatives of the nobility, high officials and the military, and some church or university officials sat in them. The right to vote not only excluded women, but also included circles of the poor through a census right to vote . In addition, the rights of the people's representative bodies were restricted by the monarch's right to convene and dismiss. The parliaments discussed taxes or draft laws , but only in a few states, such as Württemberg, did they have the right to rule on the state budget.

A significant deficit in the implementation of the declarations of intent of the founding treaty was the handling of the constitutional question. Article 13 of the Federal Act stipulated that “a state constitution should be introduced in all federal states ”. This term was ambiguous and allowed different interpretations, especially since it was not specified in what period the provision had to be fulfilled. Was this the demand for a constitution based on Western European models or did the old pre-revolutionary estates' advisory bodies mean? So the design of Article 13 ultimately remained a question of power. Until the revolution of 1848/49, the constitutional question was decided in line with Metternich's state conservatism.

The different interpretations of the constitutional term soon split the states into three groups. Before federal regulations to the contrary were drafted, some of them gave themselves a constitutional constitution . Again some of these linked to the experiences from the time of the Rhine Confederation . This also included Bavaria, where according to the constitution of 1808 a revised version had already been drawn up in 1815, but without initially coming into force. It was only when a turning point in constitutional policy became apparent at the federal level that a second constitution was passed in 1818. Baden also enacted a comparatively modern constitution in 1818 , while in Württemberg it lasted until 1819 due to representatives of old-class and constitutional positions.

Other states did not change their old status at all or even returned to the old constitution. In 1821, 21 monarchies and four towns ruled by patricians had such an older type of “landed estate”. The Mecklenburg aristocratic regime was particularly ancient . In the Kingdom of Saxony, the conditions from the time of the old Empire continued until 1832. In the Kingdom of Hanover, after the end of the Kingdom of Westphalia, a profound restoration of the old conditions quickly began. The situation was similar in Braunschweig and Kurhessen.

In Austria, too, the old country-class organs remained in the sub-areas. In contrast, the Metternich system successfully prevented the creation of a constitution for the entire state. Although this could not prevent the advance of the southern German states , it supported the other countries in their restoration efforts. A crucial question was whether Austrian diplomacy could succeed in preventing a state constitution in Prussia as well. If this succeeded, the urge for a constitution could be regarded as contained and the trend could even be reversed sooner or later. If this does not succeed, the constitutional states beckoned to an increase in power that could have decisively restricted the scope of action of the presidential power Austria. Behind the scenes, Metternich therefore resolutely argued against the constitutional plans that were being pushed forward in Prussia, primarily by State Minister Hardenberg . Last but not least, Metternich was able to rely on a conservative court party , the so-called camarilla , around the Prussian crown prince, later Friedrich Wilhelm IV . Since the position of the constitutional supporters in Prussia was not to be underestimated either, both sides initially balanced each other out. However, the position of Hardenberg and the reformer was decisively weakened. Even his approval of the planned internal repression ( see below ) did not prove to be useful in saving the constitutional project in Prussia. With the revolutions of 1820 in southern Europe, particularly in Spain , the scope for constitutional development continued to decrease. When Hardenberg fell out of favor with the king, it was in fact the end of the plans for a state constitution. Like Austria, Prussia remained without a state constitution until 1848.

Carlsbad resolutions

Metternich used the fraternities and the emerging liberal movement to assert a threat to public order. The first occasion he used was the Wartburg Festival on October 18, 1817. The individual states and the German Federation with police and informers took action against the fraternities in particular. At the Aachen Congress of 1818, Austrian policy of restorative restructuring of the Confederation and cooperation with the conservative Berlin court party made further progress. Internationally, the proponents could be sure of the support of Russia. The possibility of a frontal attack against the reformers was offered by the murder of the writer August von Kotzebue by the student Karl Ludwig Sand on March 23, 1819.

Thereupon Metternich met in Teplitz with the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III. and Hardenberg, where the later Karlsbad resolutions were prepared. The advocates of a liberal-constitutional development among the members of the German Confederation - additionally put on the defensive by a press campaign by Metternich's confidante Friedrich von Gentz - could hardly counter this and had to agree to the Austro-Prussian agreement in a "Teplitz punctuation".

Immediately afterwards, a secret conference took place in Karlsbad from August 6 to 31, 1819, attended by ministers from the ten largest federal states. In long debates, they agreed on a whole bundle of federal bills that contained repression measures against the opposition at universities and schools, especially against the student fraternities, and meant the abolition of freedom of the press. However, in the face of resistance from Bavaria and Württemberg, Metternich did not succeed in implementing the old-class constitution as a binding model for all federal states. The Federal Assembly decided everything else extremely quickly and in a constitutionally questionable manner. A breach of the constitution, however, was already in the Karlsbad Conference itself, which had bypassed the Bundestag as the sole competent body under Article 4 of the Federal Act and disregarded the right of the smaller federal states to have a say.

Restorative restructuring of the federal government

Despite its initial openness, the image of the German Confederation is shaped by this function as the “executor of restoration ideas” ( Theodor Schieder ). The federal government acquired the character of a patronizing police state, which was concerned with enforcing “law and order”. The University Act made it possible to dismiss politically suspicious professors, the fraternities were banned, and the Press Act, contrary to Article 18 of the Federal Act, introduced strict censorship . A seven-person Mainz Central Investigation Commission was set up to carry out these measures . This had a high degree of authority over the police authorities of the individual states.

Most states implemented these provisions in state law to varying degrees. Resistance was strongest in Bavaria, Württemberg and Saxony-Weimar . Baden, Nassau and Prussia, on the other hand, showed particular zeal . These even went beyond federal regulations. Immediately after the Karlovy Vary resolutions, the so-called demagogue persecution of unpopular people began. A number of professors suspected of the opposition were dismissed, such as Jakob Friedrich Fries and Lorenz Oken in Jena , Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette in Berlin , Ernst Moritz Arndt in Bonn and the brothers Carl and Friedrich Gottlieb Welcker in Giessen . In addition, numerous fraternity members were to jail or imprisonment convicted.

Nevertheless, these measures and the resulting socio-political conditions were far removed from those of the dictatorships of the 20th century. There was public opposition to the Karlsbad resolutions, for example from Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling , Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann or Wilhelm von Humboldt . Some of the critics, such as Johann Friedrich Benzenberg , warned that the measures would make a revolution possible in the long term.

Metternich's policy of conservative restructuring of the Confederation was completed at the Vienna Ministerial Conferences from November 1819 to May 1820. They served to close the open points of the Federal Act in the restorative sense. The result was the "Federal Supplementary Act", better known under the name Vienna Final Act of May 15, 1820. It laid down an interpretation of the constitutional article of the Federal Act, according to which, on the one hand, the existing constitutions had validity, but on the other hand the monarchical principle was firmly anchored and the possible rights of the estates or parliaments were limited.

economy and society

The German Customs Union

In contrast to the mandate of the Federal Act, the German Confederation did not succeed in standardizing economic conditions in the German states. In particular, the fragmentation of customs policy hindered industrial development. Important impulses for changes in this area came from outside. With the lifting of the continental blockade, German traders were in direct competition with British industry. A General German Trade and Industry Association called for customs protection. His spokesman, the economist Friedrich List , also called in a widespread petition for a dismantling of internal German customs barriers. It is true that the Bundestag dealt with a possible tariff settlement on Baden's initiative as early as 1819 and 1820, but without an agreement. The overcoming of internal German tariffs therefore took place outside the federal organs at the level of the participating states themselves.

The initiative for this came primarily from Prussia. In view of the fragmented national territory, the government of this state had a self-interest in overcoming the customs borders. In Prussia itself, all internal trade barriers had fallen in 1818. Outwardly, only a moderate protective tariff was levied. Both the large landowners interested in free trade and the commercial economy threatened by foreign competition could live with it. The neighboring states of Prussia immediately protested against the hindrance of their economy by the high Prussian transit tariffs. There was considerable pressure from this to join the Prussian customs system. The principality of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen joined the system first, followed by various other small Thuringian states. In other countries, the Prussian customs offensive triggered violent counter-reactions. As early as 1820, Württemberg planned to found a customs association of the “Third Germany”, that is, the states of the German Confederation excluding Austria and Prussia. However, the project failed due to the different interests of the countries addressed. While the relatively highly developed Baden advocated free trade, the Bavarian government demanded a protective tariff. After all, there was later an agreement between Württemberg and Bavaria and the establishment of a South German customs union . As a counter-foundation to the Prussian activities, a Central German Trade Association was established in 1828 from Hanover, Saxony, Kurhessen and other states, which was supported by Austria . The states undertook not to join the Prussian alliance, but did not form a customs union themselves.

The Prussian government, especially Finance Minister Friedrich Christian Adolf von Motz , increased its efforts in the face of these foundations. The first larger state to join the Prussian customs area was the Grand Duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt in 1828. The Central German Zollverein began to break up as early as 1829 when the Electorate of Hesse left it. In the same year there was a contract between the Prussian and the southern German customs union. This paved the way for the establishment of a larger German customs union. In 1833 the Prussian and South German customs areas officially merged. Saxony and the Thuringian states were added in the same year. On January 1, 1834, the German Customs Union came into force. In the following years Baden, Nassau, Hesse and the Free City of Frankfurt became members. For the time being, Hanover and the northern German city-states were still missing, some of which did not join until the era of the establishment of the Empire; Hamburg took its time until 1888.

In order to protect the sovereignty of the smaller states, attempts were made to uphold the principle of equal rights in the negotiations on the association's structures. The highest body was the customs union conference, for whose decisions unanimity was required. These resolutions then had to be ratified by the individual states. At the same time, joining the federal government meant giving up sovereign rights to an intergovernmental institution. The contract was initially concluded for eight years. It was automatically renewed if it was not terminated by one of the members. Despite all theoretical equality, Prussia had a preponderance, in particular the conclusion of trade agreements with other states was in his hands.

The economic effects are not entirely clear, however. Although direct taxes could be reduced in some states, the Zollverein was not a targeted instrument to promote the industrial economy. Rather, the guiding principles of most of the leading politicians were still shaped by a medium-sized pre-industrial image of society. Although the Zollverein facilitated industrial development, it did not provide any decisive growth impulses. The function of the association as the engine of German unity, which was later repeatedly emphasized, was also not the intention of the politicians of the individual states. However, some contemporaries, such as the Prussian Finance Minister von Motz, were well aware of the political dimension. He saw the planned Zollverein as early as 1829 as a tool for the implementation of a small German nation state under Prussian leadership. Metternich, in turn, saw it as a threat to the German Confederation in 1833.

The industrial revolution

If the political development in the German Confederation was largely characterized by restorative tendencies, one of the most momentous economic and social changes in this area occurred during this period with the industrial revolution. At the beginning of the federal government, Germany was still predominantly agricultural. In addition, there were a few older commercial densification zones with more traditional production methods, and there were only a few modern factories.

At the end of the era, industry was clearly decisive for economic development and shaped society, either directly or indirectly. Unlike in Great Britain, where the textile industry was the decisive engine for industrial development, in the German Confederation the railways provided the necessary growth boost. The age of the railroad began in Germany with the six kilometer long line between Nuremberg and Fürth of the Ludwigseisenbahn-Gesellschaft in 1835. The first economically important line was the 115 kilometer long line between Leipzig and Dresden (1837) built on the initiative of Friedrich List . In the following years, railway construction experienced rapid growth. In 1840 there were only 580 kilometers, in 1850 it was already over 7,000 kilometers. The growing demand for transport led to the expansion of the rail network, which in turn increased the demand for iron and coal. The number of miners in the emerging Ruhr area rose from 3,400 in 1815 to 9,000 in 1840.

The iron and steel industry experienced a similar boom, as the example of Krupp shows. While the company only had 340 workers around 1830, it was already around 2000 by the beginning of the 1840s. Mechanical engineering directly benefited from the construction of the railway. Since the 1830s, the number of manufacturers of steam engines and locomotives increased . These included the machine factory in Esslingen , the Saxon machine factory in Chemnitz , August Borsig in Berlin , Josef Anton Maffei in Munich , the later so-called Hanomag in Hanover , Henschel in Kassel and Emil Keßler in Karlsruhe . At the top was undoubtedly the Borsig company, which produced its first locomotive in 1841 and its thousandth in 1858, and with 1,100 employees rose to become the third largest locomotive factory in the world.

However, industrial development was not a nationwide phenomenon, but a regional one. At the end of the German Confederation, four types of regions can be distinguished:

- The first includes clearly industrialized areas such as the Kingdom of Saxony , the Rhineland, the Rhine Palatinate and also the Grand Duchy of Hesse .

- A second group includes regions in which some sectors or subregions appear to be pioneers of industrialization, but the entire area cannot be considered industrialized. These include Württemberg , Baden , Silesia , Westphalia , the Prussian province of Saxony and Nassau .

- A third group includes regions in which there were early industrial approaches in some cities, but which otherwise exhibited comparatively low commercial development. This includes the Kingdom of Hanover and the Province of Hanover , Upper and Middle Franconia .

- There are also areas that were largely agricultural and whose trade was mostly craftsmanship. These include, for example, East and West Prussia , Posen and Mecklenburg .

Pauperism and Emigration

Especially in the non-industrialized areas, the population did not benefit from the new economic developments. Not infrequently, the collapse of the old trade and the crisis of the handicrafts aggravated social hardship. This mainly affected the often overstaffed manufacturing trade. In rural society, since the 18th century, the number of farms in the lower or small peasant classes with little or no arable land had increased significantly. The commercial employment opportunities - be it in the agricultural trade or in the home trade - had made a major contribution to this. With the crisis in the handicrafts and the decline of the home industry, significant parts of these groups found themselves in dire straits. These developments contributed significantly to the pauperism of the Vormärz. In the medium term large parts of the factory workers came from these groups, but for a longer transition period industrialization meant the impoverishment of many people. At first, the standard of living declined with the opportunities for profit, before a large part of the home traders became unemployed. The best known in this context are the Silesian weavers .

Since most of the new industries initially gave work to the local lower classes, internal migration played a subordinate role in the first few decades. Instead, emigration appeared to be a way of overcoming social hardship. In the first decades of the 19th century, the quantitative scope of this type of migration was still limited. Between 1820 and 1830 the number of emigrants fluctuated between 3,000 and 5,000 people per year. Since the 1830s, the numbers began to increase significantly. The main phase of pauperism and the agricultural crisis of 1846/47 had an impact here. The movement therefore reached its first peak in 1847 with 80,000 emigrants per year.

Emigration itself took on organized forms, initially through emigration associations and increasingly through commercially oriented agents, who often worked with disreputable methods and cheated their clientele. In some cases, especially in south-west Germany and especially in Baden, emigration was encouraged by the governments in order to defuse the social crisis.

In the early 1850s, the number of emigrants continued to rise, reaching 239,000 people a year in 1854. Social, economic and also latent political motives were mixed. A total of around 1.1 million people emigrated between 1850 and 1860, of which a quarter came from the real division areas of southwest Germany.

The working classes

| area | 1816 | 1865 | Growth in percent |

Average growth rate per year in% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prussia (federal territories) | 8,093,000 | 14,785,000 | 83 | 1.2 |

| Schleswig-Holstein (Schleswig not a member of the federal government) |

681,000 | 1,017,000 | 49 | 0.8 |

| Hamburg | 146,000 | 269,000 | 84 | 1.2 |

| Mecklenburg-Schwerin | 308,000 | 555,000 | 80 | 1.2 |

| Hanover | 1,328,000 | 1,926,000 | 45 | 0.7 |

| Oldenburg | 220,000 | 302,000 | 37 | 0.6 |

| Braunschweig | 225,000 | 295,000 | 31 | 0.5 |

| Hessen-Kassel | 568,000 | 754,000 | 33 | 0.6 |

| Hessen-Darmstadt | 622,000 | 854,000 | 37 | 0.6 |

| Nassau | 299,000 | 466,000 | 56 | 0.9 |

| Thuringian states | 700,000 | 1,037,000 | 48 | 0.8 |

| Saxony | 1,193,000 | 2,354,000 | 97 | 1.4 |

| to bathe | 1,006,000 | 1,429,000 | 42 | 0.7 |

| Württemberg | 1,410,000 | 1,752,000 | 24 | 0.4 |

| Bavaria (with Bavarian Palatinate) | 3,560,000 | 4,815,000 | 35 | 0.6 |

| Luxembourg / Limburg (federal territory) |

254,000 | 395,000 | 56 | 0.9 |

| Austrian Empire (federal territory) |

9,290,000 | 13,856,000 | 49 | 0.8 |

| Others | 543,000 | 817,000 | 51 | 0.8 |

| German Confederation | 30,446,000 | 47,689,000 | 57 | 0.9 |

From around the mid-1840s, the composition and character of the lower social classes began to change. One indicator for this is that since around this time the term proletariat has played an increasingly important role in social discourse and superseded the concept of pauperism until the 1860s. Contemporary definitions show how differentiated this group was in the transition from traditional to industrial society. These included manual workers and day laborers, journeymen and assistants, and finally factory and industrial wage workers. These “working classes” in the broadest sense made up about 82% of all employed persons in Prussia in 1849 and together with their members they made up 67% of the total population.

Among these, the modern factory workers initially formed a small minority. In purely quantitative terms, there were 270,000 factory workers in Prussia (including those employed in the factories) in 1849. Including the 54,000 miners , the overall figure of 326,000 workers is still quite small. That number rose to 541,000 by 1861.

Women's work was and remained widespread in some sectors such as the textile industry , but women were hardly employed in mining or heavy industry. In the first few decades in particular, there was also child labor in the textile industry . While women's and child labor were of minor importance in some sectors, both remained widespread in agriculture and the domestic sector .

The merging of the initially very heterogeneous groups into a workforce with a more or less common self-image initially took place in the cities and was not least a result of the immigration of rural lower classes. The members of the pauperized strata of the Vormärz hoped to find more permanent and better paid services in the cities. In the course of time, the initially very heterogeneous stratum of the “working classes” grew together, and a permanent social milieu developed thanks to the close coexistence in the cramped workers' quarters .

The bourgeoisie

The 19th century is considered to be the time of the breakthrough in civil society . In purely quantitative terms, however, the citizens never made up the majority of society. In the beginning rural society predominated, and in the end the industrial workers were on the point of outnumbering the citizens. But there is no doubt that the bourgeois way of life, its values and norms shaped the 19th century. Although the monarchs and nobility initially maintained their leadership role in politics, this was shaped and challenged solely by the new national and bourgeois movements.

However, the bourgeoisie was not a homogeneous group, but was made up of different parts. The old urban bourgeoisie of craftsmen, innkeepers and traders stood in continuity with the bourgeoisie of the early modern period . This gradually passed down into the petty bourgeoisie of the small tradesmen, individual masters or shopkeepers. The number of full citizens was between 15 and 30% of the population until well beyond the 19th century. After the reforms in the Confederation of the Rhine, in Prussia and later in the other German states as well, they lost the exclusivity of their citizenship status due to the civic concept of equality and the successive implementation of the municipalities . With a few exceptions, in the early 19th century the group of old townspeople persisted in the traditional ways of life. In the urban bourgeoisie, class tradition, family rank, familiar forms of business, class-specific expenditure on expenditure counted. By contrast, this group was skeptical of the rapid but risky industrial development. Numerically, this group formed the largest citizen group until well into the middle of the 19th century.

Beyond the old bourgeoisie, new civic groups have emerged since the 18th century. Above all, this includes the educated and economic bourgeoisie. The core of the educated bourgeoisie in the territory of the German Confederation was predominantly made up of senior employees in the civil service, in the judiciary and in the higher education system of grammar schools and universities, which expanded in the 19th century. In addition to the civil servant education bourgeoisie, freelance academic professions such as doctors, lawyers, notaries and architects only began to gain in importance in the 1830s and 1940s. It was constitutive for this group that membership was not based on class privileges, but on performance qualifications.

Self-recruitment was high, but the educated middle class in the first half of the 19th century was quite receptive to social climbers. About 15–20% came from a rather petty bourgeois background and made it through high school and university. The different origins were leveled out by training and similar groups of people.

The educated bourgeoisie, which made up a considerable part of the bureaucratic and legal functional elite, was politically undoubtedly the most influential bourgeois subgroup. At the same time, however, it also set cultural norms that were more or less partially adapted by other bourgeois groups up to the working class and even by the nobility. This includes, for example, the bourgeois family image of the publicly active man and the wife caring for the house and children, which dominated into the 20th century. The educated bourgeoisie was based on a new humanist ideal of education. This served both as a demarcation against the privilege-based nobility and against the uneducated classes.

With industrial development, a new economic bourgeoisie appeared alongside the urban and educated bourgeoisie. The German form of the bourgeoisie came from the group of entrepreneurs. By the middle of the century, research estimates that several hundred entrepreneurial families can be expected here. In the following decades up to 1873 their number increased to a few thousand families, but the economic bourgeoisie was numerically the smallest bourgeois subgroup. In addition to industrialists, it also included bankers, capital owners and, increasingly, employed managers.

The social origins of the economic citizens varied. Some of them, such as August Borsig, were social climbers from craft circles, a considerable number, such as the Krupps, came from respected, long-established and wealthy city-middle-class merchant families. It is estimated that around 54% of industrialists came from entrepreneurial families, 26% came from families of farmers, self-employed artisans or small traders, and the remaining 20% came from the educated middle class, from families of officers and large landowners. Hardly any industrialists came from working-class families or the rural lower class. Already during the industrial revolution, the type of social climber lost weight. While around 1851 only 1.4% of entrepreneurs were academically educated, by 1870 37% of all entrepreneurs had attended a university. Since the 1850s, the economic bourgeoisie began to separate itself from the other bourgeois groups through its lifestyle - for example by building representative villas or buying land. Some of these began to orientate themselves towards the nobility in their lifestyle . However, only the owners of large companies had the opportunity to do so. In addition, there was a middle class of entrepreneurs, such as the Bassermann family , who set themselves apart from the nobility and followed a distinctly middle-class ideology.

History and political developments

The history of the covenant can be divided into different phases:

The first phase from 1815 to 1848 is known as the time of restoration and pre- march. Some authors start the pre-march with the year 1830, others with the year 1840. In pre-march, the epoch before the March revolution of 1848 , political oppression and political awakening were already grappling with each other.

The second phase is the period from the March Revolution to the restoration of the Bundestag in 1851. During this period the Frankfurt National Assembly set up an imperial government and drafted an all-German constitution , which, however, due to the refusal of the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. To accept the imperial dignity proposed to him , was not legally effective. After the suppression of the revolution in 1849, Prussia tried to attempt its own unification ( Erfurt Union ) and Austria tried to accede its entire area to the German Confederation ( Greater Austria Plan).

The third phase is the reaction era up to 1859 with a subsequent phase of renewed reform discussion. The reaction time was marked by the attempt to restore the German Confederation in its pre-revolutionary form and by the suppression of all opposition movements by the authorities . The last major attempt at federal reform was the Frankfurt Princely Congress of 1863, which Prussia failed. The political contradiction between Austria and Prussia over the question of the administration of Schleswig-Holstein and the outcome of the German War led to the end of the German Confederation.

The German Confederation did not have a successor in the legal sense . In the Peace of Prague between Prussia and Austria, it was determined that the property should be divided and that federal officials kept their pension rights. A commission regulated the details. The Peace of Prague allowed Prussia to reorganize north of the Main line, from which a federal state emerged, the North German Confederation of 1867. The confederation of states in southern Germany , however, was not realized.

The July Revolution in the German Confederation

Despite the police measures taken during the Restoration period, the German Confederation and its member states did not succeed in weakening the liberal and national opposition in the long term; even in the 1820s they repeatedly flared up and sometimes violently opposed the prevailing politics. Since they could no longer be openly active, the national movement, for example, looked for outwardly unsuspicious forms of expression. In the course of the Greek revolution , philhellenism also served as a replacement for the banned German movement.

Its continued existence became clear to contemporaries, especially since the July Revolution spread from France to the member states of the Federation in 1830. The renewed revolution in France had made it clear to the governments that a Europe-wide restorative stabilization threatened to become an episode. Conversely, the events in France have strengthened the liberals' hopes for political change. It should not be forgotten that some federal states were directly affected by the Belgian revolution , the November uprising in Poland and the events of the Italian Risorgimento . Within the federal borders themselves, revolutionary unrest broke out, which could temporarily be fought militarily by the federal government or the individual states, but in the medium term gave impetus for reforms in the sense of constitutionalism and marked the beginning of a process of political radicalization that intensified in the 1940s.

Revolutionary unrest broke out in around 1830 in the Duchy of Braunschweig . The ruling Duke Charles II had repealed the constitution in a kind of coup d'état in 1827 against the express will of the federal government and introduced an absolutist form of rule. The resulting political dissatisfaction mixed with social problems. Both together eventually led to the storming of the ducal palace and the dismissal of the Duke because of " government incompetence " by a parliamentary committee which met. A possible federal execution did not take place because the duke had discredited himself from the other members of the federal government in previous years.

In Electorate Hesse, too, Elector Wilhelm II had lost all trust due to his absolutist behavior and his mistress economy. Here too, political protest was associated with social discontent. The bourgeois opposition succeeded in channeling the discontent of the lower classes in their favor. The government finally had to give in and agree to the introduction of a liberal constitution drawn up primarily by Marburg constitutional lawyer Sylvester Jordan . The elector himself had to abdicate in favor of his son. The new constitution was actually very progressive for the time. The right to vote was broader than in other states and the parliament consisted of only one elected chamber. In addition, there was a catalog of basic rights , ministerial responsibility , the right to represent the people's budget and other elements. Despite the far-reaching concessions, which were unprecedented in the German Confederation until 1848, the new ruler's governance proved no less despotic than that of his predecessor. In the following years, the country was therefore characterized by far-reaching political conflicts.

In Saxony, revolutionary unrest first developed in the cities and spread to the villages of weavers and other textile manufacturers. There, political criticism of the old-fashioned constitution and anti-Catholic resentment (against the royal family) were combined with protests of craftsmen and workers. In Saxony, too, the bourgeois opposition, in cooperation with the ministerial bureaucracy, managed to channel the protests and to implement a new constitution and a gradual reform of the state and society.

In the Kingdom of Hanover, the protest was directed against the old-class feudal system. The real opponent was not the distant English king, but the leading minister Ernst Graf von Munster . In Hanover, too, riots broke out in many places, and in Göttingen there was even a putsch led by three private lecturers, which, of course, was quickly put down. Nevertheless, the old government could not hold out and a new constitution came into being, which, however, still contained considerable class elements. But at least the peasants' liberation began here too . A new situation arose in 1837 when, after the death of William IV, the personal union with Great Britain ended and Ernst August von Cumberland became King of Hanover. The latter rejected the oath on the constitution and finally declared it invalid, without the German Federation protesting against it. The aftermath that caused a sensation in the German public was that seven professors from Göttingen ( Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm , Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann , Georg Gottfried Gervinus , Heinrich Ewald , Wilhelm Eduard Albrecht and Wilhelm Eduard Weber ) declared that they would continue to feel bound by the constitution. The Göttingen Seven paid for this attitude with their dismissal from university service. The public protests across Germany forced the Hanover government to make its course a little less reactionary.

Politicization in the 1830s and Federal Response

An expression of the politicization was not least of all the increasing importance of political-oppositional journalism. Heinrich Heine and Ludwig Börne were among the most important authors who were already in exile at the time . Together with younger people like Karl Gutzkow or Heinrich Laube , they represented the literary movement of Young Germany . Apparently, their criticism of the temporal situation was so hated by those in charge of politics that the Federal Assembly in 1835 issued a ban on the grounds of blasphemy and immorality. In Hesse, Georg Büchner and the pastor Ludwig Weidig founded the “Society for Human Rights”, and Büchner published the Hessian Landbote in this context .

How deep the opposition already reached into society is also shown by the range of the bourgeois festival culture, initially in the form of the “ Polish clubs ” as a form of solidarity with the Polish uprising. Starting in the Bavarian Palatinate, a widespread opposition organizational movement was formed in 1832 with the German Press and Fatherland Association , which had numerous local associations, especially in federal states in which the conflicts of the July Revolution had been particularly profound. Their goal was the rebirth of Germany in a democratic sense and in a lawful way. The organization was banned by the authorities shortly after it was founded. However, the journalists Johann Georg August Wirth and Philipp Jakob Siebenpfeiffer in particular were able to organize the Hambach Festival as the “National Festival of the Germans” to support the association . With an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 participants, this was the first major political mass demonstration in federal history. In addition to Germans, Poles and French also took part in the event and in addition to the colors black, red and gold , the Polish eagle could also be seen. There were only a few nationalist tones; rather, despite all the differences, the speakers pleaded for freedom and equality of peoples alongside national unity. Despite all the revolutionary pathos, however, the participants could not, as the initiators hoped, agree on further revolutionary measures or even the proclamation of a revolutionary representative body.

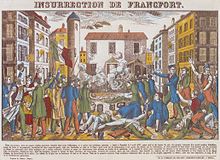

Without realpolitical calculation, as it was carried through in the discussions at the Hambacher Fest, intellectuals from the fraternities tried with the Frankfurt Wachensturm (1833) an attempted coup against the organs of the federal government. The attempt to seize the city of Frankfurt, the federal envoy to arrest and set up a revolutionary central power in order to set a signal for a general revolution, failed after the storm on the Frankfurt police station through betrayal and through the rapid deployment of the military.

In the face of the crisis, the German Confederation showed itself to be able to act. By deploying the military, he put an end to the aftermath of the Frankfurt guard storm. After the repression of the federal government of the 1820s gradually came to an end and even the Central Investigation Commission had ceased its activities in 1827, the revolutionary unrest and the politicization in the wake of the July Revolution once again intensified the measures taken by the authorities against the opposition. The initiative for this came directly from the Federal Assembly. After the Hambach Festival, censorship was tightened again by federal law. In addition, all political associations, gatherings or celebrations were banned. This largely meant the end of political activities outside the state parliaments. These measures were tightened again in the "six articles" of June 28, 1832 and the "ten articles" of July 5, 1832. In addition to the extension of the assembly bans to folk festivals, the law of the state parliaments was also interfered with. Petitions were no longer allowed to violate the monarchical principle, and budget rights and the right to speak in parliaments were restricted. Federal law thus offered the states a legal tool to block further developments in the constitutions. The federal measures were again enforced and executed by a central political investigation agency. By 1842 it had investigated approximately 2,000 cases and prompted the states to initiate numerous criminal proceedings. The main focus was again on the fraternities. In Prussia membership was now even considered high treason. Overall, at the Vienna Ministerial Conference of 1834, the member states committed themselves to a tough course of repression, strict control of civil servants and universities, curtailing the rights of the state parliaments and suppressing freedom of the press. Objections from France and Great Britain were dismissed as interference in domestic affairs.

Political pre-march

Formation of the political camps

In the 1840s, as in 1830, the mixture of social problems with political developments was repeated to an increasing extent. The decade was marked by an awareness of the crisis based on real foundations. In the bourgeois public, pauperism and the social question became the most debated issues. With the rejection of the repression of the 1930s, the political camps began to develop more clearly.

Political liberalism became the central bourgeois emancipation ideology. It stood in the tradition of the specific form of the Enlightenment in Germany. Liberalism emphasized individualism, was against the authoritarian state and bondage to estates, was based on the recognition of inalienable human and civil rights. However, social inequality was taken for granted. In addition, the concept of liberalism as a society was deeply rooted in the pre-industrial world. The target utopia was ultimately a classless, medium-sized society of independent livelihoods in town and country. Liberalism saw the core of the people in the middle class, which of course extended broadly from the craftsmen to the educated middle class. Nonetheless, this meant that the lower strata, as supposedly politically incapable of making judgments , should be excluded from the decision-making process, for example through a census vote . However, individual advancement should be facilitated, for example, through better schooling. Classic German liberalism was therefore anything but egalitarian and threatened to become a defense ideology when it turned out that social advancement was not taking place in any significant way. In terms of constitutional law, constitutionalism was not called into question. Basically, they only called for reforms aimed at greater civic participation. Not least because the French Revolution and in particular the Jacobin reign of terror played a negative role in the discourse of the leading liberals , the principle of popular sovereignty was rejected. On the other hand, for reasons of foreign and domestic policy, the Liberals advocated the creation of a unified nation-state. For them, the German Confederation was primarily a product of the restoration and had discredited itself through its policy of repression. However, it should not be overcome in a revolutionary way, but should be democratized evolutionarily in gradual negotiations, for example through the creation of a federal parliament. The leading role in early liberalism was primarily taken by the educated middle class. In view of the closeness of this class to the state, but also as a bulwark against a possible revolution, some of them, such as Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann or Johann Gustav Droysen, advocated a strong monarchy, albeit bound by a constitution and controlled by a parliament. Since around the July Revolution, numerous business citizens, especially from the Rhineland, have also spoken out. These included David Hansemann , Ludolf Camphausen , Friedrich Harkort and Gustav Mevissen . The early Liberals were in close contact with one another through correspondence, travel, and publications. The State Lexicon published by Karl von Rotteck and Carl Theodor Welcker also created a common theoretical basis. In addition, there was the daily press such as the Deutsche Zeitung, which has appeared in Heidelberg since 1847 . In the same year, the foundation for a liberal party was created during the Heppenheim conference .

An independent democratic-republican camp began to split off from liberalism in the 1830s . Together with the Liberals, the Democrats were opponents of the existing restorative system. Behind this common opposition the contradictions between the two currents took a back seat. It was clear, however, that the Democrats were fundamentally questioning monarchical constitutionalism rather than gradually developing it. In addition, they aimed not only at legal equality, but at least also at political equality for all citizens. This meant the demand for universal and equal active and passive suffrage. In addition, there was the demand for a reform of the school system and the free teaching at all educational levels. For the Democrats, the principle of popular sovereignty formed a central basis. While this was not always clearly stated, it did mean that the Republic was the ideal form of government for the Democrats . In addition to political equality, there was the goal of the greatest possible social equality. Unlike the liberals, they did not rely on the individual's will for advancement, but demanded active support from the state and society. In contrast to the socialists , however, the way was not seen in a revolution in property relations, but in a gradual equalization of the same. At the time, the demand for a progressive tax system or state-guaranteed minimum wages appeared revolutionary in this context . In the 1940s, the Democrats were much more threatened by state repression than the Liberals. In addition to the emigrants, Robert Blum , Gustav Struve and Friedrich Hecker developed into influential figures among the Democrats. It was not until 1847 that they constituted themselves as a political party with the Offenburg program and distinguished themselves as the “whole” from the liberal “halves”.

One consequence of the repression of the 1830s was that the number of political emigrants rose steadily. They included writers such as Büchner or Heine, but also numerous unknowns. It was mainly from this group that the first noteworthy beginnings of a socialist movement emerged. In exile, opposition parties and groups have been formed since then, mainly from the radical democratic spectrum, and in some cases from the labor movement as well. In Switzerland, as part of Giuseppe Mazzini's “ Young Europe ”, a German section was created as Young Germany . In Paris , the League of the Righteous was created from forerunners . Its leading figure was Wilhelm Weitling . In 1847 he renamed himself the League of Communists and at the beginning of 1848 adopted the program of the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels .

During the time of the German Confederation, conservatism developed into a conscious conception of the state and society as a result of the French Revolution . Its representatives rejected rationalism , the Enlightenment, the principles of the French Revolution such as equality of citizens, popular sovereignty and the idea of the nation state. Even the enlightened absolutism and the centralized bureaucratic state they were critical of and deplored the de-Christianization of the world. Instead, they advocated class-corporate structures and the monarchical principle . In terms of social policy, they emphasized the god-willed inequality of people. As early as 1816, Karl Ludwig von Haller's main work, “Restoration of Political Science”, was one of the most influential works of conservative thought in German-speaking countries. It was not until the pre-March period, particularly under the influence of Friedrich Julius Stahl, that a somewhat more differentiated trend emerged that no longer rejected the constitutional state. Under the influence of the July Revolution, the Berliner political weekly paper became a political mouthpiece for the conservatives.

Even the political Catholicism has its roots in pre-March. The Cologne turmoil played a central role. This dispute between the Catholic Church and the Prussian state was sparked by the differing views on the question of the Catholic education of children with parents from different denominations. There was also a dispute over Hermesianism , a rationalistic theological trend that had fallen under the verdict of the Vatican . The Catholic Archbishop of Cologne Clemens August Droste zu Vischering had canceled the compromise negotiated with his predecessor on the question of mixed marriages and criticized the state for not dismissing the followers of Hermesianism from university service. The conflict reached its climax when the Prussian government arrested the archbishop. This triggered a wave of protest within Catholic society, which was combined with older anti-Prussian resentments, especially in the Rhine Province and the Province of Westphalia . In a flood of pamphlets, the freedom of the church was demanded by the state, but paradoxically also the recognition of the privileges of the church and the strengthening of its position in the educational system. As the organ of the emerging political Catholicism, Joseph Görres founded the historical-political papers for Catholic Germany in 1838 .

Rhine crisis and the beginning of organized nationalism

As a confederation of states, the German Confederation was embedded in international politics. It is not uncommon for external events and developments to have an impact on the internal conditions of the Federation. This was the case in 1830 with the repercussions of the Belgian and French revolutions on political life in Germany. The interaction was similar in 1840. France was diplomatically isolated through its independent politics and the support of Mehmed Ali in Egypt, since the other great powers were not interested in a collapse of the Ottoman Empire . The diplomatic defeat of France in the Orient crisis led to an increase in national passions there. Edgar Quinet put forward the much-noticed thesis that the domestic political stagnation was closely related to the foreign policy weakness of the July monarchy . In memory of the Napoleonic conquests, the public demanded that the Rhine border be regained. Prime Minister Adolphe Thiers could not avoid this. In order to achieve a revision of the London treaty concluded to settle the Eastern Crisis , France put Austria and Prussia (two of the signatory states) under pressure through armaments measures on its eastern border. Since Louis Philippe considered this policy too risky, a new government was installed, which returned to Metternich's policy of stability. The Rhine crisis was effectively over quickly.

In the area of the German Confederation, however, the Rhine crisis sparked long-lasting national passions. With the Rheinlied by Nikolaus Becker “You shouldn't have it, the free German Rhine” , the poem Die Wacht am Rhein by Max Schneckenburger, but also the Song of the Germans by Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben , popular opportunities for identification emerged. If the liberal Hoffmann limited himself to German unity, there were also chauvinistic tones. Ernst Moritz Arndt, for example, not only called for the defense of the Rhine, but also called for Alsace and Lorraine from France in a song .

- “This is what the slogan sounds like: to the Rhine! Across the Rhine! / All Germany into France. ” (The Pan-German Association of the Empire took its name from these lines.)

The national enthusiasm was reflected in the explosive expansion of the men's choir movement. National song festivals became mass events in the Vormärz. In total there were around 1,100 clubs with 100,000 members in 1848. For the same reasons, the gymnastics club movement experienced a considerable boom in the 1840s and it reached a similar size as the singing clubs. Only recently has the German Catholic movement around Johannes Ronge been described as another notable nationally oriented organization , which strived for a German national church and had up to 80,000 members in 240 parishes. These and similar organizations strengthened the enforcement of the "national idea" beyond students and educated citizens to the petty bourgeoisie and the upper class.

German Confederation and the Revolution of 1848/49

With the exception of Berlin and Vienna , where there had been unrest after the outbreak of the March Revolution, the liberal opposition, supported by peaceful gatherings and protests, quickly prevailed in almost all federal states without significant resistance. But also in Austria and Prussia the rulers had to give in to the pressure. In almost all federal states, the so-called March governments took over the affairs of government from mostly moderately liberal forces. However, with the exception of Bavaria, where King Ludwig I also had to resign because of his affair with Lola Montez , the princes remained in office.