Political parties in Germany 1848–1850

The political parties in Germany 1848–1850 emerged shortly before the outbreak of the revolution in 1848/1849 . A large number of local and, in some cases, state associations emerged, while supra-regional organization was only partially successful.

In the Frankfurt National Assembly, the members of parliament were grouped according to common fundamental convictions and interests. As a rule, the parliamentary groups were named after the inns (conference rooms) in which the members of parliament met. Despite a few splits and regroupings, the factions were fairly stable and well organized. At times, the question of small German / large German superimposed the division into political groups.

After the end of the National Assembly, the center-right remained active and participated together with the right in the Erfurt Union Parliament , while the left was already being persecuted or boycotted the undemocratic election to the Union Parliament. In the Union Parliament, the right-center, constitutional or right-wing liberals, had a large majority, but Prussia's union project failed in 1850 because of the attitude of the medium-sized states and Austria. This was when the real reaction era set in, and it was only towards the end of the 1850s that it slowly became possible again to form political associations.

Designations

The contemporaries of the years 1848–1850, but also later historians, used many different names for the political currents and associations of the revolutionary era. Sometimes these terms refer to a more general left-right scheme, sometimes to larger ideologies such as liberalism or conservatism, sometimes there were already specific names of parties or factions based on the city or the restaurant in which they met.

According to the left-right scheme, a distinction was made between the center, the left and the right. The very broad middle, the center, was divided into a left and a right center. Especially for the left and right, but also with reference to ideologies , expressions such as extreme, extreme or decisive (i.e. tending to the left or right) or moderate (tending towards the middle) were used to identify more precisely: the moderate left, the decisive Left, the determined liberals, the moderate constitutional, the extreme right, etc.

At that time, there were two opposing principles on which power in the state could be based: traditionally it was the monarch, and in the age of constitutionalism there was also representation of the people. From an ideological point of view, the monarchical principle on the one hand and popular sovereignty or democracy on the other . The decided right was purely monarchical and wanted to give a parliament as little a say as possible; the left was purely democratic and called for a republic with a strong representation of the people and a weak government. Movements in between wanted to see both principles realized:

- The liberalism advocated a constitutional monarchy. Right-wing liberals (of the right-wing center) wanted to see a real balance between monarch and popular representation and only allow the people to be elected by the wealthy. Left-wing liberals (of the center-left) wanted more power for the parliament and a right to vote that would allow many men to vote.

- The Democrats wanted a strong representation of the people, which came about under universal suffrage . The moderate democrats could also imagine a constitutional monarchy with a rather weak kingship. The determined Democrats tended to abolish the monarchy.

Parties in the pre-march

Ban on parties

In the German pre-March , i.e. the years or decades before the revolution of 1848, there were no parties for various reasons. The view still prevailed that the people's representatives should represent the people in their entirety and should focus on the common good, not on the interests of individual groups. In the rules of procedure of parliaments, there were often fixed seating arrangements to prevent parliamentary groups from forming.

Above all, however, parties, that is, political associations, were banned. The freedom of association (the freedom to form associations) was mentioned in almost no German state constitution, although the constitutional doctrine of the time included it among the basic rights. The old corporate state, but also Rousseau, rejected the freedom of association, while the North American constitution protected it with the first amendment of 1791.

The reactionaries in the German Confederation from 1815 strictly rejected the freedom of association as well as the freedom of the press, and the murder of the poet Kotzebue in 1819 provided the pretext to ban all fraternities at the universities (Section 3 of the Federal University Act, i.e. not just the secret associations) , under threat of heavy penalties and the prohibition to hold public office later. The club system then moved to areas outside the university. The Hambach Festival of 1832, a large demonstration for freedom and national unity, provided the occasion for new repression. On July 5, 1832, the German Confederation issued ten articles that forbade all political associations and extraordinary public festivals, as well as political speech at public festivals and the wearing of badges in public. The repression of the federal government (in addition to that of the state laws) ensured that the population increasingly rejected the federal government, while the line between political and non-political associations could not be clearly drawn. Manfred Botzenhart: "In the exuberance of the March movement, the path from the regulars 'table to the electoral committee, from the reading club, from the' Society Harmonie 'or the' Citizens 'Museum' to the political association was probably often quickly completed."

Early party theory

According to Karl Theodor Welcker in the Staatslexikon of 1843, the association also included political associations. They could be designed to be permanent, had a fixed program and organization, and were basically open to all citizens. For Welcker they were a political organ to criticize, but also to support the assemblies of the estates and generally to articulate public opinion. As far as parliamentary groups in the people's assemblies are concerned, he refers to the English example.

In 1844 Friedrich Rohmer distinguished between radicalism, liberalism, conservatism and absolutism, which he compared with the ages of man: boy, young man, man, old man. According to him, the two middle parties (in the sense of currents) had most in common. The state encyclopedia named the democratic party the only one that represented the general interests of humanity, while the remaining three (absolutism, church, bourgeoisie) pursued special interests. What exactly the interests of mankind consist of is not specifically defined.

Heinrich von Gagern was one of the politicians in the Vormärz and then in the March Revolution, who early on called themselves a “party man” and thus wanted to get away from the negative connotation of the term “party”. One party, in his opinion, served to gain recognition for his views; You can only have political influence through a party.

Parties in the Revolution 1848/1849

In the actual March Revolution of March and April 1848, local associations were immediately founded everywhere. They wanted to put forward the March demands until they were realized by the rulers in the federal government or in the country. In addition, they were deliberately vague and not divided into individual parties. In the second half of March an attempt was made to create organizations at state level (in Baden , Grand Duchy of Hesse , Saxony and Württemberg ).

In the election for the National Assembly in April / May, the demarcation between such parties or electoral associations hardly played a role. The election was indirect in most countries, and the electors chose local celebrities known from local or state parliaments. After the election, many associations fell asleep again, until the debates in the National Assembly on central power and the Frankfurt Democratic Congress moved people and encouraged party formation. The Democrats' Congress tried to form a Germany-wide republican party, its central committee condemned the National Assembly as hostile to the people because it had elected an irresponsible imperial administrator (a kind of substitute monarch). In return, the Liberal-Constitutionalists sought national unification.

Organizations

The supraregional association organizations corresponded to two basic types:

- Most constitutional-liberal associations wanted the local associations to be as independent as possible. A “suburb” ran the business and ensured contacts with and between the local associations. The suburb could not speak or make decisions on behalf of it all.

- The Democrats and Republicans chose a hierarchical organization with local associations, associations at county or district level, and a central committee. They also paid more attention to party discipline in the local clubs.

The associations met at the state level approximately every three months, with the delegates of the affiliated associations meeting on the first day and a public assembly of the people taking place the next day.

First foundation attempts

The Offenburg People's Assembly of March 19, 1848 still united leftists and liberals and formulated a series of demands that democratize the political system and the abolition of noble privileges. Above all, they wanted to arm the people in order to be able to enforce the demands. To this end, "patriotic associations" should be founded in the individual places, which should unite at the district and county level up to the state level. The demand for weapons brought the clubs closer to a "revolutionary combat unit", according to Manfred Botzenhart.

The “Patriotic Associations” of the Mainz radicals at the end of March, on the other hand, should consist of a few people, including a representative of local self-government and the commander of the vigilante group. They should promote improvements in the life of the state and arm the people. A city's committee should maintain contact with the surrounding area and form a central state body with other cities. Such organizational plans were rather incomplete sketches and were not carried out.

Following the pre-parliament, a democratic central committee was formed in Frankfurt , which on April 4, 1848 dared to form a party. He saw himself connected to the democratic faction in the pre-parliament and wanted to win votes for the left in the upcoming national assembly election. Local associations were happy to reformulate the goals: an overly clear striving for a republic could have led to a loss of votes or conflicts with the police. There should only be one provincial level between the central and local levels. The organizational plan focused entirely on the election and made no provisions for the time after that. Nothing is known of provincial associations and notable influences on the election, and when the Democrats' Congress invited to Frankfurt in June, it had to be started all over again.

From March 26th the Patriotic Associations of Württemberg started from Göppingen . Here determined and moderate liberals jointly called for support for the March demands through local associations that were supported by district associations. The district clubs kept in close contact with the main club in Stuttgart. The call formulated general requirements for candidates for election to the National Assembly, such as certain virtues, knowledge and patriotism. About 50 local associations joined in the spring. In July, a program discussion split the Democrats from the Patriotic Associations, which then founded popular associations. The remaining constitutional members in the Fatherland Associations elected a regional committee of 15 members, which in turn elected a select committee and a board of directors.

In Saxony, on March 28, the democrats called for the establishment of patriotic associations. Here the local associations formed district associations and the district associations formed a state association. One of the clubs was elected as the main club, whose committee also served as the regional club's committee. The first general assembly took place on 23./24. April took place and already counted 116 delegates, from 43 associations with a total of 11,463 members. It passed a program with the commitment to popular sovereignty and parliamentary monarchy. Thereupon republican clubs developed in the patriotic associations of Leipzig and Dresden .

On April 6th, Biedermann and Göschen called in Leipzig to form “German clubs”. These were for a German federal state and in the individual states for constitutional monarchies on a democratic basis. In mid-May there were said to have been 42 associations with 8,000 members, later thirty associations with 10,000 members. However, there were double memberships which, according to the statutes, were not prohibited. The upper middle class was the social base of the German clubs, workers were hardly represented.

The formation of associations stopped at the borders of the individual states, plans by the moderate democrats and the constitutional members were unsuccessful. But since the end of March political Catholicism formed the “ Pius Associations for Religious Freedom”, which wanted to see the independence of the church from the state and basic rights such as freedom of the press realized. Only Catholics were allowed to become members. At first only local associations were founded, which merged with a main association at the level of the diocese, then 17 central associations were invited to the Mainz Katholikentag in October 1848, which founded the Catholic Association of Germany . The delegates of the local associations elected a suburb as the executive body for the general assembly. The association made social demands, but had no general political program and thus not the character of a party.

Left and Left Center

Democrats-Republicans

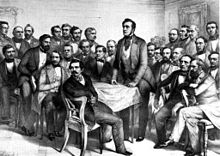

In June 1848, the Democratic Congress in Frankfurt gathered 234 delegates from 89 associations in 66 cities. Under the president Julius Froebel he represented the extreme left including some communists with the commitment to the social republic. The main committee of the Democratic-Republican Party , as it was called in the Frankfurt resolutions, was to have its seat in Berlin . Three members (Froebel, G. Rau, Hermann Kriege ) have already been elected, the rest should be determined by the democrats in Berlin ( Adolf Hexamer , Eduard Meyen ). Germany was divided into 18 districts on the map. District committees should coordinate the work of the local associations. The central committee was unable to represent the party externally and to issue instructions to the sub-organizations, which Congress had refused. According to Botzenhart, the party was typical of the Republicans of the time, who lacked political judgment due to excessive self-esteem, who had no common political theory and who were rife with mutual distrust.

A three-person provisional central commission should already publish the congress reports before the formation of the central committee in Berlin. But the commission also spread political demands such as a petition for Friedrich Hecker . The left of the National Assembly should leave it and form its own assembly. This overstepping of competencies resulted in a failure that tended to damage the Republican cause while the central committee was more cautious and wanted to act on legal ground.

The (modern) seeming organization of the left in Mainz, co-founded by Ludwig Bamberger, was unusual . The elaborate statutes described the composition of the governing committee and did not make its meetings public. The committee was elected for one year and decided on the admission of club members. Driven primarily by elementary school teachers, a large number of democratic-republican associations were formed on July 13th after the founding of a district association, in December there were around a hundred in the province of Rheinhessen alone.

While the number of left-wing associations grew, there were only about a dozen monarchical-constitutional associations in the Grand Duchy of Hesse, for example. In October 1848 the competent Hessian minister asked the Reich Ministry in vain to take measures against the Democrats. The Hessian government did not dare to act itself, while Baden, Württemberg and Bavaria stepped in to the ban. In Württemberg, for example, this was justified in July 1848 with the communist direction of the republican party. The sources and research situation do not allow precise information to be given about the political associations of the time and their supraregional connections.

From October 26 to 31, 1848, another democratic congress or party congress took place in Berlin. After a long debate about the abolition of the central committee, a new one with three members was set up. The organization remained fairly decentralized. From the organizational statute, the word republican was deleted from the self-designation democratic-republican because many local associations were bothered by it. In a declaration by the Congress, however, the goal of a democratic-social republic was found. An organizational connection with the workers' associations was rejected by the congress.

The congress called for new elections to a German parliament because the mandate of the national assembly had expired. He then fell out over the official participation in a popular assembly on the counter-revolution in Vienna. The moderate minority (with Congress Chairman Bamberger) left the Congress because they feared that the people's assembly would be called for action; but the congress has no mandate to organize a revolution. The opposition in the party thus broke out on the question of revolutionary tactics, said Manfred Botzenhart.

Central March Association

In the fall of 1848 one observed not only the stagnation of left party foundations, but also the strengthening of the counter-revolutionary forces. Unlike the Republicans, the actual Democrats had not even set up a supraregional party. On November 21, 1848, the Donnersberg, the Deutsche Hof and the Westendhall, i.e. the three left-wing parliamentary groups in the National Assembly, met again for a joint assembly. Rappard von der Westendhall proposed a central association of the three factions. A draft program was already available two days later: the aim was to implement democracy by legal means.

The Donnersberg and the Deutsche Hof joined the association, while the Württemberger Hof (the left-wing liberals) refused to join. The Westendhall released its members to join, which led to the faction falling apart. The local associations of the organization (or the provincial associations in Austria, Prussia and Bavaria) formed a central committee for each country; If clubs in a country had different orientations, there could be several central committees in the country. The clubs kept their programs and organizational forms. The members who joined the Frankfurt National Assembly formed a central association.

The Central March Association had a board of three members, initially Raveaux (Westendhall), Trützschler (Donnersberg) and Eisenmann (non-attached). In addition to Raveaux, Schüler / Jena (Deutscher Hof) and L. Simon (Donnersberg) later officiated. There was an office in which there was at least one full-time secretary in addition to volunteers. Because of the feared entry of Prussian troops into Frankfurt on May 15, 1849, the files of the association including the registry were burned. But it looks like the organization was not very effective, partly because the board was already heavily burdened by tasks in parliamentary groups, committees and in the national assembly. The Central March Association commented on current political issues and called for mass petitions to parliaments or governments.

According to its own information, the Central March Association had around 950 local associations with a total of half a million members by March 31, 1849. In April and May, the Reich constitution campaign brought many more clubs to the table. The sideline of the Republicans and the constitutional members delimited the Central March Association programmatically, but with its broad program and loose organization it should be seen more as an umbrella organization than a party.

After the rejection of the imperial crown by the Prussian king, the left of the Donnersberg left the Central March Association because they had promised more "energy". Most of those who left joined the survey in Baden and the Palatinate. Trützschler was finally executed, and death sentences were passed against nine other Donnersbergers. The majority of the Central March Association stuck to its legal methods and also had success in Württemberg, where the king was forced to accept the imperial constitution. A general assembly of the March clubs took place on May 6th in Frankfurt, where one spoke of the preparation of the revolutionary struggle (with the formation of military clubs), but did not call for the struggle itself. The Central March Association ended with the rump parliament in Stuttgart, and the local associations gave up disappointed or were banned.

Constitutional Liberals

The “constitutional association” of Nuremberg can serve as an example of party formation in the monarchical-constitutional direction. He called for a constitutional monarchy on a democratic basis and chose a suburb for the organization that had to change every six months. The long time the association was founded shows a low level of willingness to participate in politics; According to the government, there was only a comparable "Association of Friends of the Constitutional Monarchy" in Würzburg and three others in Middle Franconia, three in Upper Franconia, six in Swabia and four in Upper Bavaria. A closer connection between these clubs could not be determined.

In Baden, too, such associations had hardly any weight, as was the case in the Grand Duchy of Hesse, with the exception of the association in the capital Darmstadt . In many cases, constitutional and moderate democrats, i.e. the right and left center, remained in a joint association. The question of monarchy or republic usually caused a split. Right-wing associations received some protection from the government, for example in Hanover when a patriotic association separated from the national association.

At the end of June 1848, in response to the Democratic Congress, the Cologne Citizens' Association called for interconnected (monarchical) constitutional associations. In July, a people's assembly took place in Kösen (today Saxony-Anhalt) , at which 16 associations from Thuringia , neighboring Prussia and Saxony were represented. The People's Assembly expressed its confidence in the National Assembly and decided to found provincial associations for the Prussian Province of Saxony and the Kingdom of Saxony, with a “general German constitutional central association” as the final goal soon. On July 15, the Provincial Association for Prussian Saxony was founded in Halle, an association of the Thuringian Constitutionalists in Gotha on July 31, and the German associations already existed in Saxony.

On July 7, 1848 Westphalian constitutional representatives met in Dortmund . German unification and the achievements of the revolution hardly played a role there; they stood for old Prussia. Despite the resistance of the Bielefeld Liberals , more than 160 delegates from 60 associations came together in Duisburg on July 16, which took over the Dortmund program for a constitutional monarchy. The addition “on the broadest democratic basis” was rejected. On January 6th, again in Dortmund, the congress of the Rhenish-Westphalian constitutionals even thanked the Prussian king for the constitution that had been imposed. From an organizational point of view, the Cologne Citizens' Association was recognized as a suburb, to which the local associations should report on a monthly basis.

A congress in Berlin on July 22, 1848 attracted around 150 delegates from around 90 associations. The contrast between the supporters of Prussia and those of Germany became clear, with the decree of homage strongly polarizing; Although the resolutions of the National Assembly were declared binding and the election of the Reich Administrator welcomed, the Congress also spoke out in favor of a pronounced federalism . How exactly the constitutional monarchy should look like remained open. Some observers already doubted the possibility of establishing an all-German constitutional party in view of the differences.

Another impulse came from the Kassel Citizens' Association with its 11,000 members. While in Kurhessen itself a constitutional state association could only be founded on May 18, 1849, the Kassel people already propagated a "national association" for popular sovereignty on September 7, 1848. On November 3rd, the founding assembly came together in Kassel, with representatives from local or regional associations, mainly from Saxony and Northern Germany. The Prussians and the Thuringians were absent. Left-wing participants left the Congress because they unsuccessfully demanded a people's veto over decisions of the National Assembly; other participants wanted to support not just any majority of the National Assembly, but the democratic-constitutional direction. The latter motion received a narrow majority, but to avoid a split the final decision on it was left to a later Congress, which did not come about. So this approach to a national liberal party also failed due to inability, disinterest and internal tensions.

conservative

Prussia

The Association for the Protection of Property and for the Promotion of the Prosperity of All Classes of the People was founded in Stettin on July 24th, 1848 and was presented in the Neue Preußische Zeitung (Kreuzzeitung) and in the Deutsche Zeitung at the end of August 1848. The program promised measures for small and medium-sized businesses and small-town businesses as well as credit institutions for smallholders; However, the impetus for the establishment came from the Prussian nobility, who rejected a property tax reform. The association with local, district and provincial associations had a central committee to which each provincial association sent five members. The committee in turn elected an executive board with a chairman.

The only general assembly of the association, the so-called Junker Parliament , took place on 18./19. August in Berlin. It attracted a lot of attention, but political activity was very limited. Ludwig von Gerlach gave an indignant speech about the class egoism of most of the aristocratic participants: property is not just a means of personal enjoyment. The provisional club president Ernst von Bülow Cummerow also said that for your own credibility you should not only fight tax projects of the ministers, but also think about the prosperity of all classes. The association was subsequently still active as a journalist, but remained an organization of the aristocratic landowners, a class that had no members in the Prussian National Assembly (but in the first chambers of the middle states). The club did not gain any major importance.

On July 3, 1848, the Association for King and Fatherland was formed in Nauen (Brandenburg), which wanted to fight for the rights of the king and all classes of the people as well as against the republic and popular sovereignty. It was the first real party of Prussian conservatism. The anti-revolutionary, conservative founders around the Kreuzzeitung , such as Ludwig von Gerlach , recognized that the parliamentarization of a country automatically led to party formation. For itself, this party envisioned a summary of already existing associations, not a fixed organization, but shared central ideas. The line remained anynom and came from the circle around the Kreuzzeitung. About 10–20 shop stewards per province are supposed to provide the connection to the headquarters. Your association with the club should be kept secret.

The association for king and fatherland was mainly joined by the patriotic associations, the Prussian associations for constitutional royalty and the Teltower farmers association. It became visible to the public with general assemblies, after the establishment for the first time on July 14th in Magdeburg (allegedly 700 participants), then on July 24th in Halle (400 participants) and later on September 13th in Frankfurt an der Oder (200 participants) , representing ten clubs). The anonymity of the leadership harmed the association and the conservative cause, as the public correctly suspected that it was intended to conceal actual, more reactionary goals. So the association remained meaningless.

Bavaria

In May 1848 the circle around Joseph Görres founded the Association for Constitutional Monarchy and Religious Freedom in Bavaria . At that time it was the only halfway successful conservative party and feared that the church would come under the influence of increasingly secular states. The Catholic Church should stand on the side of the royal family and be "the firmest support of all social order". The association fought against liberalism and democracy, but unlike the Pius associations, allowed non-Catholics as members.

This association did not strive for a large organization or mass base and did not seek branch associations before the state elections in December 1848 (only one in Dachau is known). Only after the election was a program drawn up, to which only 23 of the 143 members of the Second Chamber supported. By February 1849, the Munich association had 1,600 members, and by the summer of 1849 around sixty local associations had been formed, most of which were headed by a pastor. Regionally, he had some considerable successes in the state elections in the summer, then the vigor dwindled, probably because it was becoming more and more reactionary, but also because the revolutionary danger was averted.

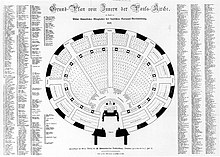

Political groups in the National Assembly

Formation and role of political groups

For a long time, the National Assembly was described as a honorary parliament, with talkative MPs who discussed freely and often changing, purely tactical coalitions that would have failed in practice. Parliamentary operations were unfinished, said Theodor Schieder , which applies in particular to the grouping according to parliamentary groups: “They were by no means firmly closed structures”, but had a “fluctuating character”, as is the “essence of the representative parliament of the elderly Style ”.

In the elections the party system was not yet fully developed, so that primarily locally known personalities, notables, were elected. The candidates could not yet be determined to support a specific political group. It was therefore surprising that the factions were formed so quickly. When the members of the National Assembly met in St. Paul's Church on May 18, 1848, they received printed notes: Those who welcomed popular sovereignty should come to the Dutch court, another note invited supporters of the constitutional monarchy to the Mainlust. In the following days, MPs met in the evenings and went to bars to find common ground with like-minded people.

Raveaux's motion on May 27 (which resulted in the question of reform or revolution) led to four different motions and almost thirty amendments (supplementary motions) in the debate. President Gagern suggested not giving reasons for the individual amendments. When the central authority was discussed a month later, appeals were of no use, after four days of debate new motions were still being tabled and the list of speakers swelled to 140 MPs. At the suggestion of Arnold Ruge , the remaining applications were collected in nine categories and two speakers per category were allowed to speak. Outsiders like Ernst Moritz Arndt protested against this approach, which received broad approval. It paved the way for factions to be formed, even if the categories did not entirely coincide with political directions. As early as June 1848, reported the MP Karl Biedermann , there were ready-made parties (in the sense of parliamentary groups). This process has been faster on the left than on the reluctant liberals.

The political groups coordinated with others and appointed their speakers in the debates, so they quickly mastered the business of the National Assembly. In less important questions they accepted different voting behavior, in more important "party matters" their statutes provided clear penalties from September at the latest, which were also applied. Dieter Langewiesche :

“The many divisions, especially in the center, which is less programmatically determined, were not a symptom of a parliamentary dignitary parliament, as has often been said, but rather the downside of the factional discipline that was enforced. This forced splits if members refused to submit. "

Despite the recognized disadvantage that minority opinions could be crushed: Even some non-attached groups were convinced of the necessity of the political groups, and in the memoirs the MEPs always described the groups as very important. Smaller parliamentary groups in the middle benefited from the fact that liberals could be flexible on individual issues without frequently breaking group discipline.

The percentages for the fractions are from October. About a third of the MPs, around 150, were "savages" or "impromptu knights", so they did not belong to any parliamentary group.

organization

There were no separate parliamentary groups in the Paulskirche. The meeting places became restaurants, after which the political groups also named. The reason for this was that the party names under which the first programs appeared in May and June were imprecise and contested: left, right center, radical democratic party, etc. The bar clearly named the group.

The statutes of a parliamentary group speak of a "party", "society" or a "political" association that was founded for joint action. You became a member by signing the statutes and the program . The existing members were able to raise objections to a new member: at Westendhall already a quarter, at the Augsburger Hof the relative majority. There were similar differences in the rules under which the group could exclude a member. At the Deutsches Hof , for example , you could only be excluded for wrong votes. Anyone who had to leave Frankfurt temporarily had to leave a contribution for the expenses (local rent, newspaper subscriptions, etc.). According to the statutes, the parliamentary groups met three or four times a week, in the evening at 7 or 8 p.m.

According to the statutes, the parliamentary groups met three or four times a week, in the evening at 7 or 8 p.m. The Landsberg stipulated that the session should only last two hours. The meetings were not open to the public, only the Deutsche Hof had temporarily held some meetings with an audience. Otherwise guests could be invited with the approval of the board of directors.

Usually one parliamentary group elected its executive committee for four weeks. He had three, five or seven members and ran the business of the parliamentary group, chaired the meetings and ensured (for example at the casino) that the five-minute speaking time was adhered to and that private conversations were avoided. In some political groups he appointed the speakers for the group or the candidates for committees. The parliamentary group members were divided into departments of ten members, each headed by a manager. If you had to send a message to all members of parliament quickly, the managing directors took care of it.

right

The deputy and Prussian general Joseph von Radowitz had invited a right-wing parliamentary group on June 4 with a draft program, which initially met in the stone house . The Austrians were still in the Socrates lodge. On September 30th, when they received a new program, the faction had already moved to Café Milani . The parliamentary group emphasized the principle of agreement with the governments and largely rejected Reich legislation. The National Assembly should not interfere in the executive action of the central authority.

Café Milani made up about six percent of all MPs. They came mainly from Prussia, Austria and Bavaria and were conservative, also federalist, so they wanted to keep the power of the individual states rather large, and legitimist, so they proceeded from the traditional rights of the monarchs.

center

The middle, the center, was the largest and most heterogeneous camp; usually it is already divided into a left and a right center (not to be confused with the Catholic center party of 1870). The most important was the casino from the right center, with 21 percent the largest group (previously, since the end of June, in the Großer Hirschgraben ). It united the supporters of the liberal, constitutional monarchy from southwest Germany, business citizens from the Rhineland and professors from northern Germany. According to a draft program by Droysen after May 22nd, particularism, anarchy and pessimism should be overcome in order to achieve “freedom, unity and power”.

The left center was dominated by the Württemberger Hof (six percent). These liberals, mostly not from Austria or Prussia, were parliamentary-democratic. Previous attempts at factions had taken place in the Holländischer Hof and in the Weidenbusch . At the beginning of June around forty MPs moved into the Württemberger Hof; this faction grew to a good hundred by the end of June.

There were splits between the casino and the Württemberger Hof. The left Landsberg (six percent) left the casino in early September. He had demanded a formal program, wanted to restrict the task of the National Assembly strictly to the drafting of a constitution, tended more towards the unitary state and advocated broad, if not democratic, suffrage. Its approximately forty members, among whom there were no celebrities, came mainly from Prussia and Hanover.

The Westendhall split off from the Württemberger Hof to the left and the Augsburger Hof to the right. The Augsburger Hof left the parent faction at the end of September because they wanted to give more support to the central authority. He advocated a parliamentary monarchy with slight restrictions on the right to vote and later joined the hereditary imperial party . Known relatives were Robert Mohl, Fallati and Biedermann.

The West Endhall was the “left in tails”, a faction formed in early August with some moderate leftists; Here one wanted more democratic elements in the constitution and expressly the universal, democratic right to vote. The first parliamentary committee consisted of Schoder, Reh and H. Simon, who also stood personally on the border between the left center and the left. At the end of November some of them joined the Central March Association , the rest became Neuwestendhall, which later went with deer to the hereditary imperial willow bush.

left

The left was republican and divided into two factions, the more moderate German court (eight percent) and the more determined, more extreme Donnersberg (seven percent). The radical democratic Donnersberg signed a program by Arnold Ruge as early as May 31 , according to which the Reich should have a unicameral parliament with universal and equal suffrage and an executive that is dependent on parliament (as an "executive committee"). The individual states were allowed to remain monarchies, but had to accept basic rights. The constitution is not to be agreed with the governments. The Donnersberg did not rule out violence in principle.

According to the program of June 4, Robert Blum's German court differed from this in that it did not explicitly demand indirect voting rights and the executive did not necessarily have to be formed from the National Assembly. The program from the end of October no longer demands the unicameral parliament as much and granted the executive in the constitution the right to postpone laws (suspensive veto). Democratic monarchies should be allowed in the individual states. The German Court always made it clear in the National Assembly that it recognized majority decisions and rejected violent solutions. He temporarily lost eleven members to the Nuremberg court (with Eisenstuck, Kolb and Loewe).

Deutscher Hof, Donnersberg and part of Westendhall joined the Central March Association at the end of November, but remained independent as parliamentary groups. Because of this “United Left”, Westendhall and the Württemberger Hof largely dissolved.

Question large German / small German

From October at the latest, the question of whether and how Austria could belong to the German Reich became more pressing; the Austrian government reacted sharply against the federal plans and even executed MP Blum on November 9th. The development led in December to the exchange of Reich Minister President Anton von Schmerling , an Austrian, by Heinrich von Gagern , who advocated a small German solution. At times the factions regrouped without completely forgetting the original classifications.

The Greater Germans met as "Mainlust". It was about the left with about 160 members who advocated a unified state, and also about a spin-off of the casino called Pariser Hof, about a hundred southern Germans and Austrians, often Catholic and federalist. However, the Parisian court and the left were very divided on other issues.

The small German or hereditary imperial party was the "Weidenbusch" with about 220 members. It was more like Northern German Protestants who came from the Casino, the Landsberg, the Augsburger Hof and partly the Württemberger Hof and occasionally the Westendhall.

Then there was the “Braunfels”, with liberals and democrats, especially Westendhall. They offered the Weidenbusch a compromise if this would strengthen the imperial constitution through democratic elements such as universal suffrage. In the important constitutional votes in March 1849, the three groups did not vote uniformly, but on the question of whether the imperial dignity should be hereditary, thanks to the Simon Gagern Pact (from Braunfels and Weidenbusch), 267 members voted yes and 263 No.

Government coalitions

When the government was formed in July 1848, not only party politics played a role, but also, for example, the inclusion of a Prussian like General Eduard von Peucker . The government was put together with the confidence of the Reich Administrator by Anton von Schmerling , who, like the other members of the Reich Ministry, belonged to the casino. When the Leiningen cabinet was completed in August , the left center was included.

The fall of the government and the change to the Schmerling cabinet in September meant that the Württemberger Hof no longer supported the government, but a coalition of Casino, Landsberg, who had fallen away from the casino, and the Augsburger Hof. The political groups formed an intergroup committee, the Commission of Nines, to maintain liaison between the governments and the government.

In December 1848, the Gagern Cabinet needed a new constellation, the Hereditary Imperial Party, in order to implement its little German program in the constitution. The Greater German Conservative Cabinets Graevell and Wittgenstein from May 1849 until the end of central power on December 20 were governments without a parliamentary basis. Against the short-lived Graevell cabinet, there was still a motion of no confidence on May 14, in which only twelve members voted in favor of the government.

Erfurt Union 1849/1850

As early as the spring of 1849 Prussia planned to unite Germany more according to its own ideas and in consultation with the middle states. The project later called the Erfurt Union failed in the summer of 1850 due to the fickle attitude of the Prussian king and the lack of interest in the middle states; for the Prussian government, unity was not a goal, but only a tactical means of gaining supremacy in the German Confederation.

Gotha direction

From June 25th to 27th, the Hereditary Emperors from the National Assembly met in Gotha to discuss the union project. The invitation was personal. Almost all the leaders of the right and left centers appeared; however, some stayed away, like Droysen, because they did not want to be compromised by Prussian politics.

There they decided on the Gotha program on June 28th. This “ Gotha post-parliament ” accepted the more conservative Prussian constitutional draft and the unequal three-tier suffrage for the state house of the Union parliament; they made reservations for a later revision. They postponed their concerns in the interests of German unity.

Of the 150 participants, 130 signed the Gotha program. They also wanted a loose organization for their party. An editorial committee under Karl Mathy took care of their organ, the Deutsche Zeitung. According to an editorial dated July 13, 1849, politics should be judged by how it stands in relation to unification; a dispute of principle should be avoided. Botzenhart calls this a realpolitik . The right wanted to return to the pseudo-constitutionalism of the Vormärz, the left wanted the direct influence of parliament on the executive, it said in an article on October 2nd. The Liberals, on the other hand, refused to allow parliament to interfere in the executive powers of the government without authorization. The revolutionary movement in May 1849 had gone too far, so a certain reaction was inevitable and necessary.

In the Erfurt Union Parliament (March / April 1850), which was already assembled according to the unequal electoral law, the Gotha people formed the so-called station party . Compared to the conservatives, they were now the “left” and the largest parliamentary group in both the elected House of the People and the House of States. Many had already sat in the National Assembly, such as Heinrich von Gagern or Friedrich Bassermann. A program of March 22nd by Ernst von Bodelschwingh was signed by a hundred MPs, it united the MPs who essentially supported the draft constitution at the time. The state should be implemented as soon as possible.

conservative

The conservatives around Friedrich Julius Stahl rejected Union policy because they saw Germany on the verge of decline without Austria's regulatory power. Besides, the revolution had just been defeated, but now its constitution, with a few amendments, is still to be implemented for no reason. The Catholics among them feared becoming a denominational minority in Germany without Austria. The brothers Peter and August Reichensperger from the Catholic Greater German group even said that Austria should have the right to object, since the establishment of a federal state would preclude it.

In general, the conservatives refused to allow Prussia to submit to the majority decisions of a union. However, they found themselves in a paradoxical situation: They stood up for loyalty to the king, but the same king supported the plan of union, so that they could not openly oppose it. This was the ultra-royalist direction. In addition to her and the Catholics, there were the state conservatives with Ministers Count Brandenburg and Otto von Manteuffel, according to which the Union could be beneficial for Prussia, and the national conservatives around Radowitz. For both groups, however, the Union constitution was still far too similar to the liberal Frankfurt Reich constitution.

In the Erfurt Union Parliament, the conservative parliamentary group called itself “Schlehdorn”, with around forty members. Her well-known members of the Volkshaus included Ludwig von Gerlach and Friedrich Julius Stahl, as well as the young Prussian politician Otto von Bismarck . Kleist-Retzow was a well-known blackthorn politician in the State House.

Between the liberal station party and the Schlehdorn was another group called "Klemme". By and large she advocated Radowitz's Union policy and advocated a limited revision of the draft constitution. The group led by Keller from Berlin had no prominent members.

Democrats

The democratic left was largely persecuted, and many democrats fled abroad. The rest were intimidated and often left politics. They sharply rejected the union project as reactionary, especially because of the right to vote. People's and workers' associations opposed the planned privileges for the rich. So the Left also boycotted the elections for the Erfurt Union Parliament according to the three-class suffrage; they viewed the participation of the Liberals as a betrayal of the agreements of the National Assembly.

Evaluation and outlook

"The beginnings of well-established political parties in Germany were in 1848," said the historian Wolfram Siemann. The parties wanted to win votes in elections. “They did it quite effectively. Large sections of the urban bourgeois population showed political maturity. It is amazing how quickly you found your way around the typical party rules. After the experience of how difficult it was for the democratic parties in the collapsing GDR to rebuild after an era of dictatorship, the events of 1848 demand all the more respect. "

Even before the final rejection of the Frankfurt Imperial Constitution, the Prussian king was already working on his own unification project, the Erfurt Union. Then in 1850 he gave in to the criticism of his highly conservative friends, for whom even the Union went too far. Pressure from Austria, the middle states and Russia was added: In the autumn crisis of 1850 a general war mood arose again, both among the national conservatives around Radowitz, among the liberals and even among the democrats. But Prussia gave in and the Union gave up, the full and Germany-wide reaction only started now.

The German Confederation abolished the freedom of association during the revolutionary period; if state laws permitted political associations, they were not allowed to join with other associations. This was de facto a general ban on parties, because without branch associations, an association was a single event without any connection. Siemann: "The five-party system that had emerged nationally during the revolution was legally smashed, criminalized and pushed underground." Associations and individual contacts could not be suppressed completely, and after about ten years a state like Prussia noticed that a political association like the German National Association of 1859 could partially support its own politics. Such associations then formed the prehistory for the formation of parties during the time of the North German Confederation .

Manfred Botzenhart:

“The liberals emerged from the revolutionary era not only defeated, but also embarrassed and afflicted with the odor of political self-surrender, while the democrats were able to take credit for having remained largely true to their principles. But since the vast majority of them did not want a new revolution either, they also did not know a way to achieve their goals, and not only liberals, but also democrats or even extreme republicans of 1848 were later ready to make an arrangement with Bismarck. "

See also

literature

- Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977.

- Dieter Langewiesche: The beginnings of the German parties. Party, parliamentary group and association in the revolution of 1848/49. In: History and Society. 4th year, volume 3: Social-historical aspects of European revolutions. 1978, pp. 324-361.

- Gerhard A. Ritter: The German parties 1830-1914. Parties and society in the constitutional system of government . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1985, ISBN 3-525-33507-5 .

supporting documents

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 315.

- ^ Judith Hilker: Basic rights in German early constitutionalism . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, pp. 291-293.

- ^ Judith Hilker: Basic rights in German early constitutionalism . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, p. 299.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 320.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 318.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 316/317.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 319.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 320/321.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 321.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 323.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 325.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 325/326.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 326–328.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 330.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 332/333.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 334–337.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 338/340.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 341/342.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 343/344.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 345-347, pp. 354-356.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 361-363.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 363/364.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 399/400.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 400/401.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 401.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 402/403, p. 405.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 406/407.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 374/375.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 377/378, p. 383.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 385/386.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 386/387.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 388/389.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 390/391.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 395/396.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 396/397.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 393.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 393-395.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 397.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 398.

- ^ Dieter Langewiesche: The beginnings of the German parties. Party, parliamentary group and association in the revolution of 1848/49. In: History and Society. 4th year, volume 3: Socio-historical aspects of European revolutions (1978), pp. 324–361, here pp. 330/331.

- ^ Theodor Schieder: From the German Confederation to the German Empire . (= Gebhardt: Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte, 9th edition. Volume 15). dtv, Munich 1984, p. 145.

- ^ Dieter Langewiesche: The beginnings of the German parties. Party, parliamentary group and association in the revolution of 1848/49. In: History and Society. 4th year, volume 3: Socio-historical aspects of European revolutions (1978), pp. 324–361, here pp. 331–333.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 416.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 416.

- ^ Dieter Langewiesche: The beginnings of the German parties. Party, parliamentary group and association in the revolution of 1848/49. In: History and Society. 4th year, volume 3: Socio-historical aspects of European revolutions (1978), pp. 324–361, here pp. 331–333.

- ^ Dieter Langewiesche: The beginnings of the German parties. Party, parliamentary group and association in the revolution of 1848/49. In: History and Society. 4th year, volume 3: Socio-historical aspects of European revolutions (1978), pp. 324–361, here p. 333.

- ^ Dieter Langewiesche: The beginnings of the German parties. Party, parliamentary group and association in the revolution of 1848/49. In: History and Society. 4th year, volume 3: Socio-historical aspects of European revolutions (1978), pp. 324–361, here p. 331, p. 333/334.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: The German Revolution of 1848/49. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1985, p. 129.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 419.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 429/430.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 430/31.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 430/431.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 419/420.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: The German Revolution of 1848/49. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1985, p. 127/128.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 420.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: The German Revolution of 1848/49. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1985, p. 128.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 420.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: The German Revolution of 1848/49. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1985, p. 128.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 424.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 421, p. 423.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 425.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 424.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: The German Revolution of 1848/49. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1985, p. 128.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 425/426.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 426/427.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 428.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: The German Revolution of 1848/49. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1985, p. 195.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: The German Revolution of 1848/49. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1985, p. 195, p. 197.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: The German Revolution of 1848/49. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1985, p. 195, p. 197.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Diss. Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a., 1997, p. 52/53, p. 122, fn. 277.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Diss. Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a., 1997, pp. 83-85.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 428.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart et al. 1988, p. 630.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart et al. 1988, p. 631.

- ^ Frank Möller: Heinrich von Gagern. A biography . Habilitation thesis. University of Jena, 2004, pp. 348–349.

- ↑ Christian Jansen: The difficult way to realpolitik. Liberals and Democrats between Paulskirche and the Erfurt Union. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. Böhlau, Cologne u. a. 2000, pp. 341-368, here p. 366.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 722.

- ↑ Peter Steinhoff: The "hereditary imperial" in the Erfurt parliament. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. Böhlau, Cologne u. a. 2000, pp. 369-392, here pp. 369/370.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 723.

- ↑ Peter Steinhoff: The "hereditary imperial" in the Erfurt parliament. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. Böhlau, Cologne u. a. 2000, pp. 369-392, here p. 370.

- ^ Hans-Christof Kraus: The Conservatives and the Erfurt Union Parliament. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. Böhlau, Cologne u. a. 2000, pp. 393-416, here p. 393, p. 394.

- ↑ Peter Steinhoff: The "hereditary imperial" in the Erfurt parliament. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. Böhlau, Cologne u. a. 2000, pp. 369-392, here p. 377.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart et al. 1988, pp. 894-896.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 768.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 768.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart et al. 1988, p. 889.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: 1848/49 in Germany and Europe. Event, coping, memory. Schöningh, Paderborn u. a. 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: 1848/49 in Germany and Europe. Event, coping, memory. Schöningh, Paderborn u. a. 2006, pp. 209-211.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: 1848/49 in Germany and Europe. Event, coping, memory. Schöningh, Paderborn u. a. 2006, p. 221.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 792.