North German Confederation

|

North German Confederation 1867–1871 |

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Constitution | Constitution of the North German Confederation of April 16, 1867 | ||||

| Official language | German | ||||

| Capital | Berlin | ||||

|

Federal Presidium - from July 1, 1867 |

King of Prussia Wilhelm I. |

||||

|

Head of Government - July 14, 1867 to May 4, 1871 |

Federal Chancellor Otto von Bismarck |

||||

| currency | no single currency | ||||

|

Foundation - August 18, 1866 - July 1, 1867 |

August Alliance of the North German Federal Constitution |

||||

| Time zone | no uniform time zone | ||||

| map | |||||

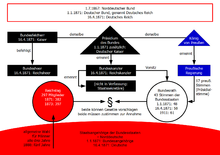

The North German Confederation was a federal state . It united all German states north of the Main line under Prussian leadership. It was the historical preliminary stage of the small German , Prussian-dominated solution to the German question that was realized with the establishment of the Empire , excluding Austria . Founded as a military alliance in August 1866, a constitution dated July 1, 1867 gave the federation state quality.

The federal constitution largely corresponded to the constitution of the German Empire of 1871 : Legislation was the task of a Reichstag , which was elected by the male people, and a Federal Council , which represented the governments of the member states (mostly duchies ). Both had to agree to pass laws. The head of the federation was the Prussian king as the holder of the federal presidium . The minister responsible was the Federal Chancellor . The conservative Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck was the first and only Chancellor in the few years of the North German Confederation.

With its numerous modernizing laws on economy, trade, infrastructure and the legal system (including the forerunner of today's Criminal Code ), the Reichstag substantially prepared the later German unity. Some of the laws were already in effect in the southern German states through the German customs union before 1871 . However, parliamentary control over the military budget was still limited, although military spending made up 95 percent of the total budget.

The hope that the southern German states of Baden , Bavaria , Württemberg and Hesse-Darmstadt would soon be able to join the federation was not fulfilled. In those countries there was great resistance to Protestant Prussia and to the Bund with its liberal economic and social policy. This was evident in the election to the customs parliament in 1868; However, this cooperation between North German and South German MPs in the Zollverein contributed to Germany's economic unity.

After a diplomatic defeat in the Spanish succession controversy , France began the war against Germany in July 1870 . It wanted to prevent a further strengthening of Prussia and a German unification under his leadership. However, after their defeat in the German War of 1866 , the southern German states of Baden, Bavaria and Württemberg had formed defensive alliances with Prussia. Because of this, and because of their better organization, the German armies were able to quickly carry the war into France.

Through the November treaties of 1870, the southern German states joined the North German Confederation. With the so-called establishment of an empire and the entry into force of the new constitution on January 1, 1871 , the federation became part of the German Empire .

Emergence

Prehistory to 1866

In addition to the Austrian Habsburg Monarchy, there had been another power in Germany since the 18th century that claimed a leading role: Prussia, which had risen to become a kingdom in 1701 and, among other things , had conquered the mineral- rich Silesia from Austria. The relationship between these two Central European great powers was called German dualism , which was characterized by rivalry, but often also by cooperation to the detriment of third parties.

The expansion of the Confederation desired by many Germans or even the transition to a federal state was prevented by Austria and Prussia: The Austrian Empire saw a German federal state as a threat to its existence because of its own nationality conflicts , and Prussia did not want the further development of the German Confederation as long as Austria alone was “ Presidential power ”was valid. As early as 1849, Prussia tried with the “ Erfurt Union ” first to create a small Germany without Austria and Bohemia , without the Habsburgs and without the German Confederation, then at least for a northern German federal state under Prussian leadership. Due to pressure from Austria, the medium- sized states and Russia , Prussia had to give up this attempt in the autumn crisis of 1850 .

As a result, there was again cooperation between the great powers, but this was overshadowed by rivalry significantly more than in the years 1815–1848. After 1859, both great powers made unsuccessful proposals for federal reform . A division of Germany into north and south was also part of it. Although they again acted together against the German states in the war against Denmark around 1864 , they soon fell out over the Schleswig-Holstein question and also fought this dispute militarily.

The Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck tried several times to find a compromise with Austria, but finally he steered Prussia towards the confrontation with Austria and, if necessary, the other states. The Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I, in turn, was unimpressed, considered Bismarck's position in Prussia to be weak and assessed his own military power as insurmountable. On June 14, 1866 , Austria obtained a federal resolution of the Bundestag on the mobilization of the Federal Army against Prussia.

German war and its consequences

In the German War of 1866, however, Prussia and its allies victorious against Austria and its allies (the kingdoms of Bavaria , Württemberg , Saxony and Hanover , the grand duchies of Baden and Hesse , the electorate of Hesse and other small states). In the preliminary truce with Austria (July 26), Prussia succeeded in reorganizing the situation in northern Germany up to the Main line . Here the expression North German Confederation appears first . Prussia had already made this arrangement with the French Emperor Napoleon III. Voted.

On October 1, 1866 , Prussia annexed four of its war opponents north of the Main: Hanover , Kurhessen , Nassau and Frankfurt . The remaining states were allowed to keep their territories with almost no changes. As a result of the incorporations, the population of Prussia rose from around 19 million to almost 24 million.

Three other war opponents north of the Main, namely Saxony, Saxony-Meiningen and Reuss older line , were obliged in the peace treaties to join the North German Confederation. The Grand Duchy of Hesse had with its province of Upper Hesse and the right bank ( Rheinhessen ) communities Kastel and Kostheim join the Federation, all north lay the River Main.

August Treaties and Constituent Reichstag

On August 18, 1866, Prussia signed an alliance treaty with a dual purpose with 15 northern and central German states, which eventually became known as the “August Alliance”. Later other states such as the two Mecklenburgs ( Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Strelitz ) joined the treaty (hence the “ August Treaties ”). For one thing, they formed a defensive alliance that was limited to one year. On the other hand, the August alliance was a preliminary contract for the establishment of a federal state.

The basis should be the federal reform plan of June 10, 1866 , which Prussia had sent to the other German states at the time. However, this plan was still very general and at that time still included Bavaria and the rest of Little Germany. The August alliance did not yet have an actual draft constitution, unlike the Three Kings alliance of 1849 for the Erfurt Union.

In the August alliance, the election of a common parliament was also agreed. This would represent the north German people in the constitutional agreement. The basis for the election were laws of the individual states. As agreed, these laws took over the Frankfurt Reich Election Act of 1849 almost literally. The North German Constituent Reichstag was elected on February 12, 1867 and opened on February 24 in Berlin by King Wilhelm I of Prussia. After long negotiations, the Reichstag , which met in Berlin's Palais Hardenberg , adopted the amended draft constitution on April 16 and had its solemn final session the next day.

Political system

federal Constitution

The Prussian Landtag and the constituent Reichstag were ruled by a national liberal - free conservative majority. The National Liberals in particular originally wanted a solution that was as radical as possible: Germany should become a unitary state under Prussian leadership. For example, the other states of northern Germany should simply have joined Prussia. Prussia, with its military might, could have forced them to do so. Bismarck, on the other hand, was looking for a federal solution. On the one hand, he did not want to deter the southern German states and their princes from joining later. On the other hand, he was concerned with his own mediating role and thus his position of power between the king, parliament and allied states.

As a result of these considerations, Bismarck strove for a north German federal constitution that concealed its Unitarian features and the power of the Prussian king. As far as possible, the new federation should outwardly resemble a federation of states . For example, in the constitution, military power was subordinate to a federal general. This designation came from the time of the German Confederation; the Prussian king had tried to become permanent general of the federal army or at least of the north German federal troops. However, the constitution made it clear elsewhere that the federal general was none other than the Prussian king.

Privy Councilor Maximilian Duncker had worked out a first draft constitution on behalf of Bismarck. After several revisions by envoys and ministerial officials, Bismarck laid a hand himself, and finally on December 15, 1866 a Prussian draft was presented to the representatives of the governments. Some of the plenipotentiaries had serious concerns, sometimes they wanted more federalism , sometimes a stronger unitary state. Bismarck accepted 18 amendments that did not affect the basic structure, and the plenipotentiaries approved on February 7, 1867. This draft was then a joint constitutional offer of the allied governments.

The draft was sent to the constituent Reichstag on March 4th. In its deliberations, the constituent Reichstag coordinated closely with the representatives of the individual states. In this way, compromises were reached that both sides could agree on. On April 16, 1867, not only did a majority in the Reichstag pass the amended draft, but the plenipotentiaries immediately approved it. The individual states then had their state parliaments vote and published the federal constitution. This process lasted until June 27th. As agreed, the constitution came into force on July 1st. Apart from a few names and details, the constitution of the North German Confederation is already identical to the constitution of the German Empire of April 16, 1871, which was applied until 1918.

In the violent deliberations of the Reichstag, Bismarck's draft had been considerably modified. The Reichstag strengthened federal competence and its own position. The National Liberal MPs Rudolf von Bennigsen succeeded, the so-called Lex Bennigsen push through: The Chancellor had the orders of the Federal Bureau (King of Prussia) countersign , to make them more effective, and thus took over the (ministerial) responsibility . It thus became an independent federal body. Bismarck himself originally wanted to see the Federal Chancellor only as an executive officer; now he was the key figure in the complicated decision-making structure ( Michael Stürmer ).

Federal bodies

The King of Prussia was entitled to the Presidium of the Confederation , a title such as "Kaiser" was waived. Not in name, but in substance he was the head of the federal government. He appointed a Federal Chancellor who countersigned the actions of the Presidium. The Federal Chancellor was the only responsible minister , i.e. the federal government (executive) in one person. Responsibility is not to be understood in parliamentary terms, but in political terms.

The Chancellor received to support its work a supreme federal authority, the Federal Chancellery (it was later in the Reich Chancellery renamed and is not with the Reich Chancellery to be confused of 1878). During the time of the North German Confederation, only one other supreme federal authority was set up, the Foreign Office taken over by Prussia . The head of the Federal Chancellery and the head of the Foreign Office were not colleagues of the Federal Chancellor, but were subordinate to him as officers authorized to issue instructions. Bismarck opposed the efforts of the Reichstag to set up proper federal ministries. In practice, Bismarck often made use of the preliminary work of the state ministries, especially the Prussian ministries, if only for lack of their own personnel at the federal level.

The member states sent representatives to the Federal Council . This representation of the member states was a federal body with executive, legislative and judicial powers. The federal government did not have a constitutional court, but the Federal Council decided on certain disputes between and within the member states.

The Federal Council exercised the legislative right together with the Reichstag, including budget approval. Diets , i.e. parliamentary allowances, were prohibited by the constitution. The general and equal male suffrage was anchored in the federal suffrage . Every North German had one vote for a candidate in the constituency in which he lived. Each constituency sent one member to the North German Reichstag. In May 1869 the federal electoral law was passed , which basically retained the provisions of the individual state laws of 1866.

The Federal Chancellor was the chairman of the Federal Council. In itself he had neither a seat nor a voice in it. But Federal Chancellor Bismarck was also Prime Minister of Prussia. In this way he had the greatest influence on the Prussian votes in the Bundesrat and thus on the entire Bundesrat. This connection between offices was not provided for in the constitution, but it was retained for almost the entire period of the North German Confederation and the German Empire .

Elections and parties

The Prussian state elections of July 13, 1866 (the primary election took place before the victory report was received from Königgrätz) was like a landslide. The Liberals lost about a hundred seats while the Conservatives gained as many. Prussian liberalism was therefore less deeply rooted in the electorate than expected. Bismarck, however, tried to come to an agreement on the outside with Austria and on the inside with the liberals in order to gain greater room for maneuver. Shortly after the war, he announced the so-called indemnity bill : he asked the state parliament to retrospectively approve his unconstitutional measures during the conflict years.

Bismarck's stance split both the liberal Progressive Party and the Conservatives. The National Liberal Party split off from the former in 1867 and the Free Conservative Party split off from the Conservatives . Both became Bismarck's pillars in parliament in the long term. The left liberals, on the other hand, carried the time of conflict with Bismarck permanently with their constitutional breaches, and the right conservatives were against concessions to liberals.

The Catholic MPs were rather weakly represented in the Reichstag of the North German Confederation. They worked together in the federal constitutional association . Even before the German Reich was founded, they united between June and December 1870 to form the Center Party , which wanted to defend the rights of the Catholic minority and the rule of law in general.

The Saxon People's Party , an anti-Prussian alliance of radical democrats and socialists, was able to send two members to the (constituent) Reichstag in February 1867, including August Bebel . In addition to his more liberal colleague, Bebel was the first Marxist in a German parliament. In the ordinary Reichstag elected in August, the SVP had three, the General German Workers' Association two. The separation of bourgeois radical democrats and socialists, one of the deepest turning points in German party history, led to the establishment of the Social Democratic Workers' Party in Eisenach in 1869 .

The parties that would later shape the empire already existed in the Reichstag of the North German Confederation: the two liberals and the two conservatives, the Catholic Center Party and the Social Democrats.

Domestic politics

Together with more liberal Prussian officials, the Reichstag embarked on an extensive reform program. Hans-Ulrich Wehler states a “wealth of initiatives, especially by the National Liberals”, which “seemed like a determined attempt to immediately prove how modern, how attractive the North German Confederation could be designed for every progressive friend in the shortest possible time - how assertive the Liberals were their politics of social modernization. ”However, the military, foreign policy, bureaucracy and court society remained autonomous, outside the rule of parliament. Otherwise, the North German Reichstag was able to "show an astonishing record of success after just under three years", to which one has to add the liberal epoch in the German Empire up to 1877. 84 national liberals, 30 progressive parties and 36 free conservatives (out of a total of 297 MPs) drove the development forward; but many important laws were also passed almost unanimously.

Over eighty laws of the Reichstag of the North German Confederation abolished numerous privileges and coercive rights; citizens were given more opportunities to live their lives more freely. The rule of law was consolidated and barriers to industry and trade removed. “Once again: some high-tension reform expectations have been disappointed. Nevertheless, a look at the twenty most important laws shows the energy with which the liberals in parliament and administration pushed ahead with their major modernization project in an astonishingly short time. "

The North German Reichstag often adopted designs from the time of the German Confederation. The innovations and standardizations that mostly continued after 1870 include:

- Citizenship Act and Passport Management

- Uniform military service

- Equality of denominations

- Free movement in the federal territory

- Removal of police restrictions on marriage

- Support residence

- General German Commercial Code

- Supreme Commercial Court

- General German exchange regulations

- Cooperative Act

- Abolition of the license requirement for public limited companies

- Trade regulations with freedom of association

- Order of measure and weight

- Postal law with uniform tariffs

- criminal code

- copyright

- Elimination of culpable detention

Germany and foreign policy

Despite other expectations, it soon became apparent that the unification of Germany was not a sure-fire success. In 1869, Bismarck therefore said that one should not rush forward by force, since that way one could only harvest unripe fruit. By moving the clock forward, one cannot make time run faster. In southern Germany , taxes had to be increased because of the army reform based on the Prussian model. In Baden, the Grand Duke could only bring the alliance with the north through parliament with the right to issue an emergency ordinance . In 1870 the Patriot Party of the Catholic Rural People overthrew the liberal Prime Minister. In Hesse-Darmstadt, the Prime Minister was still hoping for a Prussian defeat in the conflict with France in July 1870.

From May to July 1867, Bismarck initiated a reform of the Zollverein in order to bind the southern German states more closely to the North German Confederation. The “Association of Independent States ” ( association of states under international law ) with the right of veto became an economic union with majority decisions. Only the great Prussia had a veto as an individual state. The Federal Customs Council was an organ comparable to the Federal Council with government representatives from the member states ; there was also a customs parliament. It was elected according to the Reichstag electoral law, whereby in reality the Reichstag was expanded to include South German MPs.

The elections to the customs parliament took place in southern Germany in 1868. It turned out that the opponents of Prussia still represented many voters. The votes were directed against the dominance of Protestant Prussia or against liberal free trade policy; sometimes it was also about internal conflicts between states. In Württemberg all 17 MPs were anti-Prussian, in Baden 6 versus 8 small Germans, in Bavaria 27 versus 21. Most of them belonged to the conservative camp. Bismarck understood that the expansion of the North German Confederation to the south could be a long time coming; nevertheless, the south had no alternative to economic integration, as 95 percent of its trade was with the north.

Economic cooperation did not mean automatic political unity. The southern German states were on the defensive like the second French empire , but above all Napoleon III was on the defensive. domestically in a difficult situation after he had to accept liberal constitutional changes in 1869/1870. Therefore he looked for foreign policy successes; Last but not least, he wanted to compensate for German unification efforts by assigning territories. In France one spoke of the "revenge for Sadowa" (ie the battle of Königgrätz ) and meant the disappointment that Prussia and Austria made peace in 1866 so quickly that France could no longer make political demands. The possible military intervention by France caused Bismarck to be cautious at first, even if the pressure to succeed put him under pressure himself. In addition, he soon faced another serious conflict over the military budget.

Bismarck, however, shied away from instrumentalizing the national movement. In February 1870, the National Liberals called for the " Lasker Interpellation " to include liberal Baden in the federal government. Bismarck rejected this with an unusually harsh refusal: this would make the other southern German states less likely to join. The Bismarck biographer Lothar Gall assumes that he primarily wanted to preserve the previous power structure and feared an upgrading of the liberals. The same was true of a national popular movement.

At the beginning of 1870, Bismarck inaugurated King Wilhelm of Prussia in an imperial plan . Accordingly, Wilhelm should be proclaimed " Emperor of Germany " or at least of the North German Confederation. This is a strengthening for the government and its supporters in view of the upcoming elections and deliberations on the military budget. In addition, “Federal Presidium” is an impractical title in diplomatic communications. One thought was also that a German Kaiser might be more acceptable to the southern Germans than a Prussian king. Bismarck encountered resistance from the other princes in northern and southern Germany, which meant that the plan was abandoned.

diplomacy

The diplomacy of the North German Confederation was primarily determined by Prussia. The designation " Foreign Office " goes back to the corresponding title of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of the North German Confederation by the highest cabinet order of January 1, 1870, before it was renamed the Foreign Office of the North German Confederation on January 4, 1870 . With this name, Bismarck avoided the question of whether it was a ministry.

From the founding in 1867 to the merging of the larger German Empire on January 1, 1871, the relationship with the southern German states and France was decisive. There was a kind of cold war with France, which was marked by diplomatic crises and armament. The political fronts, including those with southern Germany, seemed frozen in 1870, writes Richard Dietrich.

The northern German member states retained the right to maintain their own embassies abroad and to receive ambassadors from other countries. This was not of great importance, since the member states had only a few embassies apart from Prussia.

Military policy

The Liberals originally wanted to influence the military budget in the Prussian constitutional conflict. But they had to live with the compromise that this budget had to be decided for several years (and not just one). The spending was fixed by the Reichstag until December 31, 1871. Since the military cost the federal government 95 percent of all of its federal spending, parliamentary control over the state budget was severely limited.

With the Navy of the North German Confederation , the earlier plans to build a German fleet were realized. In the short period of the North German Confederation, however, it was not possible to invest enough in building up its own naval forces. In the naval war against France in 1870/1871 , the navy therefore did not play a major role.

Franco-German War

In September 1868, the royal house in Spain had been overthrown, so that the transitional regime was looking for a new king . Bismarck made sure that Leopold von Hohenzollern , a prince from the southern German branch of the Hohenzollern , approved a candidacy. When this became known in July, public opinion in France was outraged. Leopold withdrew his candidacy, and France could have been pleased with this diplomatic victory. Napoleon III but made the mistake of demanding that the head of the Hohenzollern dynasty, the Prussian King Wilhelm I, exclude such a candidacy for the future. Bismarck gave this to the press in a shortened presentation , in which the French request and Wilhelm's rejection appeared particularly harsh. On July 19, France declared war on Prussia.

It is still a matter of dispute what part Bismarck played in the escalation of the diplomatic crisis. Christopher Clark writes that Bismarck had no control over events and had resigned himself to withdrawing his candidacy. The French willingness to go to war was due to the fact that France did not want to see its privileged position in the system of European powers endangered. Heinrich August Winkler, on the other hand, believes that Bismarck wanted war and deliberately made it inevitable through his aggravating presentation. Nevertheless, one could not speak of Bismarck's sole war guilt, because Napoleon did not want to grant the Germans the right to national self-determination. "Diverting internal dissatisfaction outwards had always been a preferred means of rule of Bonapartism."

France was isolated as the remaining powers did not see its war as justified. Contrary to Napoleon's expectations, the southern German states supported the North German Confederation because of the protective and defensive alliances with Prussia. After repulsing the French attack, the warfare shifted to France. On September 2nd, in the Battle of Sedan , Napoleon was captured and his regime capitulated. A new government of national defense continued the war until January 26, 1871. The Peace of Frankfurt followed in May . France had to pay a large amount of compensation and cede Alsace-Lorraine .

Transition to the German Empire

The southern German states of the Grand Duchy of Baden , the Kingdom of Bavaria and the Kingdom of Württemberg were still completely outside the North German Confederation in 1867, while Hessen-Darmstadt with its northern province of Upper Hesse belonged to it . In November 1870, Baden, Bavaria and Württemberg signed treaties to join the northern German federal state. The conclusion of these November treaties made it possible for the Grand Duchies of Baden and Hesse (southern Hesse) to join on November 15, 1870, the Kingdom of Bavaria on November 23, and the Kingdom of Württemberg on November 25, 1870; at the same time, the treaties agreed on the establishment of a "German Confederation". By resolution of the Reichstag on December 10, 1870, this union was given the name German Empire . The Reich essentially adopted the Federal Constitution of 1867. Thus, the German question was ultimately decided with the exclusion of Austria in the sense of the small German solution .

The accession of the southern German states to the federal government did not create a new state in terms of state and constitutional law : the reformed North German federal government existed after its constitution of the German federal government was edited - not least because of two different versions - through legal continuity under the designation “German Reich ”. The founding of the empire was therefore nothing more than the entry of the southern German states into the North German Confederation. According to the prevailing view, the German Reich was not the legal successor of the North German Confederation, but is identical with it as a subject of international law ; the latter was reorganized and renamed. The Prussian Higher Administrative Court also assumed that the international treaties of the North German Confederation would continue to apply to the German Reich, without this having been called into question with regard to a possible succession .

The constitutional historian Ernst Rudolf Huber admitted that the vast majority of constitutional lawyers assume identity. He himself emphasized, however, that the November contracts expressly speak of a new establishment. This was also the wish of the southern Germans. In Huber's view, the North German Confederation was not expressly dissolved, but it was ipso iure as a consequence of the founding of the new Confederation by the North German and South German states. Huber sees the German Reich as the legal successor to the North German Confederation, which also came into effect ipso iure . As a result, the laws of the North German Confederation continued to apply in the Reich.

Michael Kotulla, on the other hand, points out that the accession of the southern states could only take place through the constitutional path according to the North German Federal Constitution. In any case, it is astonishing how the theoretical question of “start-up or accession” is sometimes still dealt with in detail. The practical consequences are the same, since the minority at least assumes the legal succession.

Federal territory and North Germans

The establishment of the North German Confederation meant that a number of states dropped out of the process of forming a German nation-state . These were Austria, Liechtenstein , Luxembourg and Dutch Limburg . The latter was actually just a Dutch province that had belonged to the German Confederation for historical and political reasons. Luxembourg's independence was confirmed by the great powers during the Luxembourg crisis in 1867.

The North German Confederation comprised 22 member states, which were named federal states in the constitution . The total area had 415,150 square kilometers with almost 30 million inhabitants. 80 percent of them lived in Prussia. Thanks to Article 3 of the Federal Constitution, the "North Germans " enjoyed a common indigenous community so that they could move freely in the federal territory. A North German citizen was anyone who was a citizen of a member state.

Lauenburg was connected with Prussia in personal union, the Prussian king was also Lauenburg's duke (Bismarck served as the responsible minister of Lauenburg). In many lists it is not mentioned separately, although it was only incorporated into Prussia later (during the German Empire). The most important exclave of the federal government were the Prussian Hohenzollern Lands in southern Germany. The Grand Duchy of Hesse only belonged to the federal government with its parts of the state north of the Main, i.e. the province of Upper Hesse and the towns of Mainz-Kastel and Mainz-Kostheim, which were then part of the Mainz district (i.e. today's "AKK area" ).

| State | Population (1866) | Area in km² |

|---|---|---|

| Prussia , Kingdom (Prussian State) | 19,501,723 (with the annexations of 1867: 23,971,462) | 348,607 |

| Saxony , Kingdom | 2,382,808 | 14,993 |

| Hessen , Grand Duchy (Hessen-Darmstadt), only province of Upper Hesse | 118,950 (1858) | 3,287 |

| Mecklenburg-Schwerin , Grand Duchy | 560.274 | 13,162 |

| Oldenburg , Grand Duchy | 303.100 | 6,427 |

| Braunschweig , Duchy | 298.100 | 3,672 |

| Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach , Grand Duchy | 281.200 | 3,615 |

| Hamburg , Free City | 280,950 | 415 |

| Anhalt , Duchy | 195,500 | 2,299 |

| Saxony-Meiningen , Duchy | 179,700 | 2,468 |

| Saxe-Coburg-Gotha , Duchy | 166,600 | 1,958 |

| Saxony-Altenburg , Duchy | 141,600 | 1,324 |

| Lippe , Principality (Detmold) | 112,200 | 1,215 |

| Bremen , Free City | 106,895 | 256 |

| Mecklenburg-Strelitz , Grand Duchy | 98,572 | 2,930 |

| Reuss younger line , Principality (Gera-Schleiz-Lobenstein-Ebersdorf) | 87,200 | 827 |

| Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt , Principality | 74,600 | 941 |

| Schwarzburg-Sondershausen , Principality | 67,200 | 862 |

| Waldeck , Principality | 58,400 | 1,121 |

| Lübeck , Free City | 48,050 | 299 |

| Reuss older line , Principality (Greiz) | 44,100 | 317 |

| Lauenburg , Duchy (with the Prussian King as Duke) | 49,500 (approx. 1857) | 1,182 |

| Schaumburg-Lippe , Principality | 31,700 | 340 |

Evaluation and classification

Richard Dietrich called the federal government special because it was the first time in centuries that he gave at least northern Germany a state bond. He viewed the Prussian annexations critically and described the northern German federal state as a "barely veiled hegemony of Prussia". However, the federal government was designed in such a way that it later allowed southern Germany to join. In the federal government there were some innovations in the party system, such as the founding of the Catholic Center and Bismarck's cooperation with the National Liberals and Free Conservatives.

Compared to other countries in Europe , so Martin Kirsch , the German constitutional development was not very different. Around 1869/1870 France, Prussia and Italy had a similar level of development. All three states were still about to introduce social justice, in none of the three states “at this point in time the link between democracy and parliamentarism in the constitutional state was successful.” At the time of the Paris Commune , for example, it was to be shown that the internal nation-building in France was still was brittle. Wehler saw Bismarck's rule negatively in Germany, but other countries were also susceptible to a charismatic leader, such as France. The monarch had a strong position elsewhere too, not least in the military sphere. Such framework conditions of the German constitution were very European. Only the federal structure differed significantly. According to Kirsch, this has certainly hindered parliamentarisation in Germany. In general, and not only in relation to Germany, the difficult processes of nation-state formation put a strain on parliamentary-democratic development. A general male suffrage (as in the North German Confederation) introduced early on was detrimental to the stabilization of political culture.

The North German Confederation is not so much an independent epoch as a preliminary stage to the “ founding of an empire ”, as Hans-Ulrich Wehler states. This is due to the fact that the federal government only existed for about three years. In addition, there is a high degree of continuity from the federal government to the realm, both in terms of the constitution and the most important politicians such as Bismarck.

It was typical for Bismarck to take a multi-track approach. In his opinion, says Andreas Kaernbach , as a politician you can choose one of several solutions, but you cannot produce them yourself. He saw the safeguarding of the Prussian position in northern Germany as the basis of Prussian independence. This “catch-up position”, the North German Confederation, was only seen as a minimum goal. Ultimately, the Prussian-led small Germany, which he had wanted to achieve through federal reform and without war with Austria. This goal initially seemed a long way off. Nevertheless, he judged the North German Confederation to be an intermediate stage of its own value, with “its own future”.

Christoph Nonn even considers it a myth that Bismarck thought of unification as early as 1866. At that time, Bismarck had rather emphasized the old Main line and wrote to one of his sons that they needed northern Germany and wanted to spread out there. The North German Confederation was not just a stage, but a long-term goal that Bismarck has now achieved. According to Bismarck, the annexations of 1866 first had to be digested. The North German unification in 1867 and the German unification in 1871 were not the result of a detailed plan, but of flexible improvisation.

The conservative French politician Adolphe Thiers said that for France the founding of the North German Confederation was "the greatest disaster in four hundred years". Birgit Aschmann interprets this as "dramatization [...] from the interplay of material changes and mental-emotional experience components". The North German Confederation did not mean the overthrow of the European order of 1815, but a regrouping of its center. Overall, the order remained slightly changed.

flag

Article 55 of the constitution determined the flag of the Federation: “The flag of the war and merchant navy is black, white and red” . The color scheme is attributed to Prince Adalbert , it combined Prussian colors with those of the Hanseatic cities and their demands on maritime trade . On October 1st, 1867, three months after the announcement of the North German Confederation, the cloth with the Prussian eagle was hauled in and the black-white-red flag was hoisted on all Prussian ships. In 1871 the flag was adopted for the entire empire.

As a reaction of the population to the change of flag, the insidious and disrespectful poem was written on the coast:

“What is rising up on the horizon for a swathe of smoke? It is the emperor's sailing yacht, the proud 'Meteor'! The Kaiser is at the wheel, Prince Heinrich is leaning against the chimney, and at the back Prince Adalbert is hoisting the 'black-white-red' flag. And aft, deep in the galley, Viktoria Louise fries bacon. A people who have such princes have no need! Germany can never go under, long live 'black-white-red'! So we stand at the steps of the throne, and hold fast to it, and are ready to shout hurray wherever it can be done. "

The poem is attributed to Karl Rode, a first lieutenant at sea in the Imperial Navy.

Philatelic

According to Article 48 of the constitution, a unified North German postal district was created in 1868 , which was replaced by the Reichspost in 1871 . 26 stamps were issued in three currencies .

To commemorate the founding day of the North German Confederation on July 1, 1867, Deutsche Post AG issued a postage stamp with a face value of 320 euro cents. The issue date was July 13, 2017, the design comes from the graphic designers Stefan Klein and Olaf Neumann .

See also

literature

- Richard Dietrich (Ed.): Europe and the North German Confederation . Haude and Spenersche Verlagbuchhandlung, Berlin 1968.

- Eberhard Kolb (ed.): Europe before the war of 1870. Power constellation - areas of conflict - outbreak of war. R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1987.

- Ulrich Lappenküper, Ulf Morgenstern, Maik Ohnezeit (eds.): Prelude to the German nation-state: The North German Confederation 1867–1871 . Otto von Bismarck Foundation, Friedrichsruh 2017 ( Friedrichsruher exhibitions , vol. 6).

- Werner Ogris : The North German Confederation. On the centenary of the August Treaties of 1866 . In: JuS 1966, pp. 306-310.

- Klaus Erich Pollmann : Parliamentarism in the North German Confederation 1867-1870. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1985, ISBN 3-7700-5130-0 (Handbook of the History of German Parliamentarism).

Web links

- Criminal Code for the North German Confederation. Decker, Berlin 1870 ( digitized version and full text in the German text archive )

- Constitution of the North German Confederation (Internet portal "Westphalian History", digitized version)

- Alliance treaty between Prussia and the North German states of August 18, 1866

- Original text of the constitution of the North German Confederation of April 16, 1867

- North German Confederation . In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 4th edition. Volume 12, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1885–1892, pp. 217–218.

Remarks

- ↑ The constitution adopted on April 17, 1867 was largely identical to Bismarck's imperial constitution .

- ↑ See Hans-Christof Kraus , Bismarck. Size - Limits - Achievements , 1st edition, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2015; Klaus Hildebrand , No Intervention. The Pax Britannica and Prussia 1865 / 66–1869 / 70. An investigation into English world politics in the 19th century , Oldenbourg, Munich 1997, p. 389 .

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume I: Reform and Restoration 1789 to 1830. 2nd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1967, pp. 131-133.

- ↑ See Michael Kotulla : Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 439 f.

- ^ Jürgen Müller: German Confederation and German Nation 1848–1866. Habil. Frankfurt am Main 2003, Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, p. 569 f .; Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 400, 406 f.

- ↑ Göttrik Wewer , On the change in meaning of the concept of democracy in the course of history , in: Ders. (Ed.): Democracy in Schleswig-Holstein. Historical aspects and current questions , Leske + Budrich, Opladen 1998, p. 33; in detail Kurt Juergensen , The "Prussian Solution" in the Schleswig-Holstein question. Rule “from above” with participation “from below” , ibid, p. 131 ff.

- ^ Andreas Kaernbach: Bismarck's Concepts for Reforming the German Confederation. On the continuity of the politics of Bismarck and Prussia on the German question. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1991, p. 213.

- ^ Andreas Kaernbach: Bismarck's Concepts for Reforming the German Confederation. On the continuity of the politics of Bismarck and Prussia on the German question. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1991, p. 230 f.

- ↑ Article XIV Paragraph 2 of the Peace Treaty of 1866

- ^ Regulations for the implementation of the electoral law for the North German Confederation, Appendix C. , III. Grand Duchy of Hesse.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 490 f.

- ^ Klaus Erich Pollmann: Parliamentarism in the North German Confederation 1867–1870. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1985, pp. 42-44.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 491.

- ^ Klaus Erich Pollmann: Parliamentarism in the North German Confederation 1867–1870. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1985, p. 138.

- ^ Protocols of the Reichstag , accessed on June 6, 2016.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1963, pp. 649-651.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Vol. III, Stuttgart 1963, pp. 652 f.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the empire . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 665-667.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Vol. III, Stuttgart 1963, pp. 655–659.

- ↑ Michael Stürmer: The foundation of an empire. German nation-state and European equilibrium in the age of Bismarckian . Munich 1993, p. 61 f.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, pp. 501/502.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 502.

- ^ Heinz Günther Sasse: The establishment of the Foreign Office 1870/71 . In: Foreign Office (Ed.): 100 Years of Foreign Office 1870–1970 , Bonn 1970, pp. 9–22, here pp. 14–16.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the empire. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 860, 1065. Michael Kotulla: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 501.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 503.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte , Vol. 3, Munich 1995, p. 299.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler : The long way to the west. Volume 1: German history from the end of the Old Reich to the fall of the Weimar Republic. CH Beck, Munich 2000, p. 197.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte , Vol. 3, Munich 1995, p. 307.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte , Vol. 3, Munich 1995, p. 308.

- ↑ Quoted from Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte , Vol. 3, Munich 1995, p. 309.

- ^ According to Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte , Vol. 3, Munich 1995, pp. 309–311.

- ^ Richard Dietrich: The North German Confederation and Europe . In the S. (Ed.): Europe and the North German Confederation . Haude and Spenersche Verlagbuchhandlung, Berlin 1968, pp. 183–220, here pp. 226/227.

- ↑ Michael Stürmer: The foundation of an empire. German nation-state and European equilibrium in the age of Bismarckian . Munich 1993, p. 67.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte , Vol. 3, Munich 1995, p. 305.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte , Vol. 3, Munich 1995, pp. 306/307.

- ↑ Michael Stürmer: The foundation of an empire. German nation-state and European equilibrium in the age of Bismarckian . Munich 1993, p. 61.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte , Vol. 3, Munich 1995, pp. 313-315.

- ^ Lothar Gall: Bismarck's South Germany Policy 1866–1870. In: Eberhard Kolb (ed.): Europe before the war of 1870. Power constellation - areas of conflict - outbreak of war . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, pp. 23-32, here pp. 27-29.

- ↑ Michael Stürmer: The foundation of an empire. German nation-state and European equilibrium in the age of Bismarckian . Munich 1993, p. 68.

- ↑ Otto Plant : Bismarck . Volume 1: The founder of the empire. CH Beck, Munich 2008, pp. 434-436.

- ↑ In addition Eckart Conze : The Foreign Office. From the empire to the present. CH Beck, Munich 2013, p. 6 .

- ^ Richard Dietrich: The North German Confederation and Europe . In the S. (Ed.): Europe and the North German Confederation . Haude and Spenersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Berlin 1968, pp. 183–220, here p. 241 f.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German History of Society , Vol. 3, Munich 1995, p. 303 f.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte , Vol. 3, Munich 1995, p. 315.

- ↑ a b Christopher Clark : Prussia. Rise and fall. 1600-1947. Federal Agency for Civic Education , Bonn 2007, pp. 627–629.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: The long way to the west. Volume 1: German history from the end of the Old Reich to the fall of the Weimar Republic. CH Beck, Munich 2000, p. 203.

- ↑ a b Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional Law 1806–1918. A collection of documents and introductions, Volume 1: Germany as a whole, Anhalt states and Baden , Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 2005, p. 246 .

- ↑ See Peter Schwacke / Guido Schmidt, Staatsrecht , 5th ed., W. Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-555-01398-5 , p. 58 f. Marg. 164 ; on this, a letter from Federal Chancellor von Bismarck to the President of the Reichstag Simson (resolution of the North German Bundesrat regarding the introduction of the terms “German Reich” and “German Kaiser”) dated December 9, 1870 , in: documentArchiv.de (ed.).

- ↑ Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional History: From the Old Empire to Weimar (1495-1934) , Springer, Berlin 2008, § 33 Rn. 1933 .

- ↑ Art. 79 DBV (= Art. 79 p. 2 NBA in the version dated April 16, 1867): The entry of the southern German states or one of them into the Federation takes place on the proposal of the Federal Presidium by way of federal legislation.

- ^ Constitution of the German Confederation (as agreed by the protocol of November 15, 1870; with the amendments by the treaties of November 23 and 25, 1870 with Bavaria and Württemberg, including the provisions of the final protocols), entered into force on January 1, 1871 .

- ↑ Kotulla DtVerfR I, Part 1, § 7 XII.1 Abs.-Nr. 451 ; ders., German Constitutional History: From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) , Springer, Berlin 2008, § 34 Rn. 2052, 2054 .

- ↑ a b Kotulla, DtVerfR I, p. 245 fmwN

- ^ Karl Kroeschell : German legal history , vol. 3: Since 1650 . 5th edition, Böhlau-UTB, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2008, p. 235.

- ↑ Kotulla, DtVerfR I, p. 245.

- ↑ See the decision of the Prussian OVG PrOVGE 14, p. 388 ff., Where the court unproblematically assumed that the so-called Bancroft Treaty concluded between the North German Confederation and the USA on June 22, 1869, continued to apply to the German Reich .

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Vol. III, Stuttgart 1963, p. 761 f.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Vol. III, Stuttgart 1963, pp. 763–765.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 526.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), pp. 203-205.

- ↑ Numbers from: Antje Kraus: Sources for the population statistics of Germany 1815–1875. Hans Boldt Verlag, Boppard am Rhein 1980 (Wolfgang Köllmann (Hrsg.): Sources for population, social and economic statistics in Germany 1815-1875 . Volume I).

- ↑ Brockhaus, Kleines Konversations-Lexikon. Fifth edition. 1911, Retrieved April 25, 2017 .

- ^ Pierer's Universal Lexicon. 1857-1865. Retrieved April 25, 2017 .

- ↑ Pierer's Universal Lexicon. Retrieved April 25, 2017 .

- ^ Richard Dietrich: The North German Confederation and Europe . In the S. (Ed.): Europe and the North German Confederation . Haude and Spenersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Berlin 1968, pp. 183–220, here pp. 221–223.

- ^ Martin Kirsch: Monarch and Parliament in the 19th Century. Monarchical constitutionalism as a European type of constitution - France in comparison . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1999, pp. 395-397.

- ^ Martin Kirsch: Monarch and Parliament in the 19th Century. Monarchical constitutionalism as a European type of constitution - France in comparison . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1999, p. 396, 400/401.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society . Volume 3: From the “German Double Revolution” to the beginning of the First World War 1849–1914. CH Beck, Munich 1995, p. 300.

- ^ Andreas Kaernbach: Bismarck's Concepts for Reforming the German Confederation. On the continuity of the politics of Bismarck and Prussia on the German question. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1991, pp. 239–241.

- ↑ Christoph Nonn: Bismarck. A Prussian and his century . Beck, Munich 2015, p. 175.

- ↑ Otto Büsch (Ed.): Handbook of Prussian History , Volume II: The 19th Century and Great Subjects of the History of Prussia. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1992, ISBN 3-11-008322-1 , p. 347 .

- ↑ Birgit Aschmann: Prussia's fame and Germany's honor: On the national honor discourse in the run-up to the Franco-Prussian wars of the 19th century . Oldenbourg, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-486-71296-4 , p. 341 .

- ^ Andreas Kaernbach: Bismarck's Concepts for Reforming the German Confederation. On the continuity of the politics of Bismarck and Prussia on the German question. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1991, pp. 238, 239.

- ↑ Bernhard Wördehoff: Show the flag , Die Zeit No. 03/1987.

- ↑ Eike Christian Hirsch: The fine ironic art , Stern 12/1981 ( online ).