Prussian annexations in 1866

The Prussian annexations took place after the German war in summer 1866. Prussia had triumphed against Austria and its allies and forced the dissolution of the German Confederation . On October 1, 1866, it annexed four of its war opponents north of the Main line , who became Prussian provinces or parts of provinces. These were the Kingdom of Hanover , the Electorate of Hesse (Hessen-Kassel), the Duchy of Nassau and the Free City of Frankfurt . There were also smaller areas of the Kingdom of Bavaria and the Grand Duchy of Hesse (Hessen-Darmstadt).

Other war opponents north of the Main Line were preserved as states. But they had to join the North German Confederation . These are the Kingdom of Saxony , the Duchy of Saxony-Meiningen and the Principality of Reuss older line .

In some cases, the incorporation of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, previously ruled by Denmark , is one of the Prussian annexations of the time. These two duchies were not opponents of the war, but were administered jointly by Prussia and Austria. Prussia's intention to annex both was one of the reasons for the German war. In 1867 the Prussian province of Schleswig-Holstein was established.

Up until the annexations, Prussia was split into an eastern and a western half, between which Hanover and Hesse-Kassel lay mainly. For the first time since the annexations it was possible to travel from Cologne in the west to Königsberg in the east without leaving Prussian territory. In general, Prussia secured its supremacy in northern Germany, which also facilitated the establishment of the North German Confederation in 1866/1867.

The population in the affected areas was not asked. Some residents welcomed the annexation, partly because of dissatisfaction with the old rule, partly as a contribution to future German unity. Others permanently opposed the annexation. The anti-Prussian party in Hanover was the longest-lived of these movements and lasted into the 20th century. In previous Prussia itself there was a large majority in favor of the annexations.

overview

| old name | status | change | New status | Residents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duchy of Schleswig | Danish fiefdom and part of the entire Danish state , ceded to Austria and Prussia in 1864 | Austrian rights ceded in the Peace of Prague on August 23, 1866 | Part of the province of Schleswig-Holstein | 410,000 (before 1862) |

| Duchy of Holstein | Member state in the German Confederation and part of the entire Danish state, ceded to Austria and Prussia in 1864 | Austrian rights ceded in the Peace of Prague on August 23, 1866 | Part of the province of Schleswig-Holstein | 525,000 (before 1859) |

| Kingdom of Hanover | Member state in the German Confederation since 1815 | War opponents of Prussia, annexation on October 1, 1866 | Hanover Province | 1,933,800 (1866) |

| Electorate of Hesse (Hessen-Kassel, Electorate Hesse ) | Member state in the German Confederation since 1815 | War opponents of Prussia, annexation on October 1, 1866 | Part of the Hesse-Nassau Province | 763,200 (1866) |

| Duchy of Nassau | Member state in the German Confederation since 1815 | War opponents of Prussia, annexation on October 1, 1866 | Part of the Hesse-Nassau Province | 465,636 (1865) |

| Free City of Frankfurt | Member state in the German Confederation since 1815 | War opponents of Prussia, annexation on October 1, 1866 | Part of the Hesse-Nassau Province | 92,244 (1864) |

| Grand Duchy of Hesse | Member state in the German Confederation since 1815 | War opponents of Prussia, annexations of individual areas through the peace treaty of September 3, 1866 , namely: * Landgraviate Hessen-Homburg , member state in the German Confederation since 1817, inheritance to Hessen-Darmstadt on March 24, 1866, 27,563 inhabitants (1865) * District Biedenkopf * District of Vöhl * North-western part of the district of Gießen (municipalities: Bieber , Fellingshausen , Frankenbach , Hermannstein , Königsberg , Krumbach , Naunheim , Rodheim an der Bieber and Waldgirmes ) * Rödelheim * Niederursel (as far as under the sovereignty of the Grand Duchy) |

The ceded areas become part of the province of Hessen-Nassau | |

| Kingdom of Bavaria | Member state in the German Confederation since 1815 | War opponents of Prussia, annexation of three parts of the area with the peace treaty, namely: * District Gersfeld * District Orb * Kaulsdorf (Saale) |

The Bavarian districts of Gersfeld and Orb become part of the later province of Hessen-Nassau, Kaulsdorf, the district of Ziegenrück , administrative district of Erfurt , province of Saxony . |

The province of Hessen-Nassau had 1,385,500 inhabitants in 1867, the province of Schleswig-Holstein with Lauenburg 981,718 inhabitants. The Duchy of Lauenburg was ceded by Austria to Prussia in the Gastein Treaty in 1865 , which is why it does not belong to the later annexations.

In 1864 there were 18,975,228 inhabitants in Prussia. By the year 1867, the population had risen to 23,971,337 due to population growth and the annexations. The war opponents north of the Main, who escaped annexation, had the following population in 1866: Saxony 2,382,808, Saxony-Meiningen 179,700 and Reuss older line 44,100. Together with the other northern and central German states, they formed the North German Confederation in 1866/67, which had almost 30 million inhabitants. At the time, a total of 38,187,272 inhabitants lived in the countries that later became the German Empire.

prehistory

German war

The tensions between Austria and Prussia in the administration of Schleswig and Holstein had led to the German War in June 1866. The German Confederation with Austria and its allies opposed Prussia. Austria and especially the medium-sized states, the medium-sized states such as Bavaria and Hanover, wanted to maintain the status quo and therefore rejected the Prussian federal reform plan of June 10th .

The federal decision on mobilization of June 14th had already exposed the weaknesses of the German Confederation, because even the supporters had attached conditions and restrictions to their vote. At first the federal government did not succeed in agreeing on a common federal general , and when it existed, not all troops were subordinate to it. Ironically, Prussia had long called for improvements in the federal military system, and when it came down to it, the federal government was subject to Prussia, of all people, and not to an enemy from abroad. The arrears in the troops and the lack of unity between the states were an important reason for the defeat of the armed forces .

Prussia had sent its main forces (a quarter of a million soldiers) to Bohemia , which at that time belonged to Austria. In the rest of Germany his strength was only 45,000 men, which roughly corresponded to the strength of Bavaria. Hanover, Kurhessen, Nassau and Frankfurt, the later annexed states, were able to mobilize around 44,000 men together. In a joint warfare, for example with a Hanoverian-Bavarian amalgamation of forces, one could have opposed Prussia with an enormous superiority.

Under its Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck , Prussia had claimed that the federal resolution was illegal and that it allegedly led to the dissolution of the federal government. Therefore, Prussia no longer felt bound by federal law and saw the German war as a purely international legal phenomenon. This was also of importance for the annexations after the war. Following this view, which had to be accepted by the defeated opponents of the war, the later annexed states were no longer protected by federal law. As part of the debellatio of the defeated states, the annexation was allowed according to the legal understanding of the time.

Peace agreements

On June 19, 1866, Bismarck had assured the Prussian allies of their sovereignty and their territorial status. He made no promises to the neutral German states, the future of the enemy depended on the outcome of the war. Hanover and Kurhessen turned down the renewed offer of an alliance. After the victory at Königgrätz on July 4th, Bismarck sounded out the position of France. He wanted to annex Schleswig-Holstein, Hanover, Saxony, Kurhessen, Nassau and the Grand Ducal Hessian province of Upper Hesse . Emperor Napoleon III. let him know that France was largely okay with this. However, Saxony must be spared. Like the Russian Tsar Alexander , Napoleon found that the Grand Duchy of Hesse (Hessen-Darmstadt) should at least be compensated for any loss of territory through Bavarian territories. Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria also rejected a Prussian annexation of Saxony, but not one of Frankfurt. Bismarck also found that Britain would not support Hanover.

After securing the essential contents of the treaty with France (July 14th), Prussia concluded the preliminary peace of Nikolsburg with Austria and the final Peace of Prague on August 23rd . Austria recognized the dissolution of the "previous" German Confederation and also a future closer federal relationship that Prussia wants to establish north of the mainline. Austria also left Prussia free to make changes to the territory there in northern Germany. Only Saxony should not lose any territories. With this, Bismarck decided not to annex at least Leipzig and another Saxon district.

Prussia also made peace with the other remaining opponents of the war, who had to recognize the provisions of the preliminary peace or peace. The peace treaty with Hessen-Darmstadt only came about on September 3, 1866. The Grand Duchy accepted a regulation regarding its province of Upper Hesse, which was north of the Main line. This province had to belong to the North German Confederation. In addition, the Grand Duchy received the small Landgraviate of Hesse-Homburg on March 24, 1866 by inheritance. This had to cede it to Prussia.

Three war opponents north of the Main line escaped the fate of the annexation: the Kingdom of Saxony, the Duchy of Saxony-Meiningen and the Principality of Reuss older line. The peace treaties with them were concluded after the Peace of Prague (September / October). In it they had to recognize the provisions of the preliminary peace and join the North German Confederation (or the August Alliance).

Discussion about the annexations

King Wilhelm

As the responsible Prussian minister, Otto von Bismarck had to explain his policy to the monarch, King Wilhelm, so that he could support it. Wilhelm's opinion on the annexations was later mostly given on the basis of Bismarck's memoirs . However, these did not appear until several years after Wilhelm's death and were repeatedly and critically corrected in historical studies in general.

Friedrich Thimme, for example, points out that Bismarck originally wanted to reform the German Confederation. It was only later that Bismarck suddenly switched from the reform program to an annexation program: on July 8th he wanted a federal reform that included all of Little Germany. Then on July 9th, he did not mention the southern states in a dispatch, but brought the North German Confederation into play.

History, so Thimme, usually refers to the French influence: Napoleon III. found it less offensive when Prussia expanded its power in the north than in southern Germany. However, this influence cannot be proven in the sources. The difference of opinion between King Wilhelm and Bismarck is difficult to reconstruct; obviously Wilhelm always had more demands. Perhaps it was Bismarck himself who suddenly thought direct military sovereignty over Hanover and Electorate Hesse was more important than the top position in a renewed German Confederation.

In his own account, Bismarck was the prudent man who, against the resistance of the military, had sought a quick peace with Austria in order to forestall any interference by France. In fact, the army commanders basically agreed. However, it remained Bismarck's task to convince the stubborn king. According to the Crown Prince's diary , a conversation with the King on July 25 led to Bismarck's crying fit.

In Bismarck's view, Austria should be spared so that it quickly agreed to a peace and could have good relations with Berlin again in the future. According to Bismarck, a dissolution of Austria could have led to revolutionary states in Hungary and the Slavic regions. Wilhelm, however, saw Austria as the main culprit in the war and wanted to annex at least little Austrian Silesia and part of Bohemia. From Bavaria he wanted the Franconian north, which had belonged to Prussia before the Napoleonic period . In addition, parts of Saxony, Hanover and Hesse were to become Prussian. The hostile princes of Hanover, Kurhessen, Nassau and Sachsen-Meiningen were to be replaced by their presumptive heirs to the throne. Wilhelm, according to Hans A. Schmitt, was torn between solidarity for his fellow princes on the one hand and ordinary greed on the other.

Bismarck, on the other hand, doubted whether the inhabitants of a Prussian franc would really remain loyal to the Prussian crown in a later war. The necessary bitterness of the rest of Bavaria would have been detrimental to a future unification of Germany. Austrian Silesia is loyal to the Austrian emperor and also has Slavic settlements. Furthermore, Bismarck had to talk the king out of a number of ideas, such as an annexation of the Grand Ducal Hessian province of Upper Hesse; In return, Hessen-Darmstadt should have received the Aschaffenburg area from Bavaria.

In Bismarck's view, instead of annexations in northern Germany, one could have sought compensation in the constitution of the North German Confederation . But the king had just as little confidence in a constitution as in the old Bundestag and wanted to make Prussia a well-rounded area - even in the event that nothing would come of the northern German federal state. The unity of Germany could not be achieved if Hanover could once again lead its troops into the field for or against Prussia at its discretion.

The prince in question should not be left with a residual area, as the Prussian king had planned (Kurhessen: Fulda and Hanau; Hanover: Calenberg with Lüneburg and the prospect of succession in Braunschweig). According to Bismarck, both princes would then have sought to regain the old territories and would have been dissatisfied in the North German Confederation. Nassau was too close to the fortress of Koblenz , which would have been dangerous in a war with France.

Prussian Landtag

The Prussian state parliament approved the annexations with only a few exceptions, such as the progressive MP Johann Jacoby . The German war had already been waged against Germans in an alliance with a foreign power (Italy). A conquest without a referendum would not do the nation any honor and would violate the principles of law, morality and freedom. However, such views were rare even among Bismarck's opponents, both among progressives and among the Catholic faction .

A committee of the state parliament considered such referendums to be more apparent than real. (They existed when Napoleon III acquired Nice and Savoy from Sardinia-Piedmont in 1859. ) According to a speech by Bismarck in the committee, the annexations were the necessary basis for Prussia to serve the German nation. He could be sure that such a view was shared in wide circles of the bourgeoisie, including in the occupied territories. The state parliament members also saw the "right of conquest" as long as it was beneficial to the national unity of the nation.

Russia

The great Eastern power Russia wanted to see a balance of power between Austria and Prussia. The Russian Foreign Minister Gorchakov had already rejected the Prussian reform proposal in the Bundestag in April 1866. With this, Prussia is no longer pursuing politics, but revolution. However, this brief Prussian-Russian resentment did not result in Russia turning to Austria. In the run-up to the German War, Gorchakov could have imagined that the Grand Duke of Oldenburg would take over Schleswig-Holstein or that Prussia would at most be allowed to annex southern Schleswig. The small German states were to be protected against Prussian hegemony by force of arms, but only in favor of a balance between Prussia and Austria. In the second half of July, Tsar Alexander still wanted to see Austria in the German Confederation. When divided into two confederations, Austria should be at the head of the southern confederation.

When it came to the annexations after the war, Tsar Alexander spoke out against it in a letter dated August 12th. He warned his uncle King Wilhelm against the dethronement of entire royal houses and against a German parliament. However, he did not want to shake the Prussian-Russian friendship. In the meantime Wilhelm therefore tended to think again of a mere partial annexation, which the ministers and the crown prince talked him out of.

Bismarck assured Russia that Württemberg and Hessen-Darmstadt with their dynasties (closely related to the Russian one) would be treated lightly. But if Russia should continue to demand a European congress on the German peace treaty, he threatened that Prussia would proclaim the imperial constitution of 1849 and move towards a real revolution.

The personal relationships between the monarchs should not be overrated, said Eberhard Kolb. At best, they had an influence in narrowing down Prussian ambitions, for example in relation to Hessen-Darmstadt (Tsarina Marie von Hessen-Darmstadt came from its dynasty). The good understanding between the two sides continued in the years that followed. In the spring of 1868 Wilhelm and Alexander agreed that they wanted to stand by each other if France and Austria jointly attack Prussia or Russia.

Legal enforcement

Article 2 of the Prussian Constitution required that the national territory could only be changed by law (i.e. with the consent of the parliamentary chambers). This was to be used for real incorporations. Similarly, according to Article 55, if the king took over rule in "foreign realms", he had to obtain the approval of the chambers. That concerned the case of the personal union .

The state government initially wanted to make the king ruler in the four countries concerned and to obtain consent under Article 55. Such a bill reached the state parliament on August 16, 1866. The countries would have continued to exist as such and would only have been annexed via Article 2 after a certain period of time.

The state parliament, however, rejected this delay. A commission of the House of Representatives feared that the king would have received strong power in the four countries. In theory, he could even have ceded the four countries again. The Prussian constitution would not have come into force there and the state parliament would not have had budget rights. Bismarck gave in and submitted an amended bill with immediate annexation under Article 2.

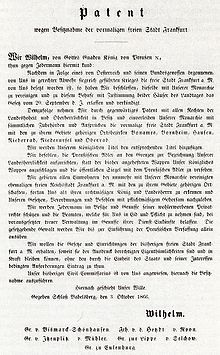

On September 7, the House of Representatives adopted the draft with 273 votes to 14. The mansion followed on September 11th with only one vote against. The King executed the law on September 20th; on this day the annexations were also announced. From October 1, 1866, the Prussian constitution came into force in Hanover, Kurhessen, Nassau and Frankfurt. This was followed by possession Seizure patents for the four countries as well as proclamations to the peoples.

By ordinance of August 22, 1867, the new Prussian Province of Hanover was given a provincial constitution. In addition, Prussia formed a new province Hesse-Nassau with

- Hessen-Kassel, Nassau and Frankfurt,

- the Landgraviate of Hessen-Homburg, which Prussia received from Hessen-Darmstadt,

- and smaller areas of Upper Hesse (from Hessen-Darmstadt), namely: Biedenkopf and Vöhl districts, north-western part of Gießen district, Rödelheim district, Hessian part of Nieder-Ursel, obtained by a peace treaty of September 3, 1866

- as well as Franconia (from Bavaria), namely: District Office Gersfeld, a district around Orb, exclave Caulsdorf, by peace treaty of August 22, 1866

For this purpose, the administrative districts of Kassel and Wiesbaden had first been established, which had formed the said province since December 7, 1868. Prussia assumed debts of the annexed countries. In an ordinance of July 5, 1867, Bismarck wanted to incorporate the active capital into the Prussian state assets. The residents and the Prussian King Wilhelm protested against this. The money, minus the debts, became provincial funds, which were decided on in the provinces.

Situation in the annexed countries

In June and July 1866, during the campaign, Prussia occupied Holstein, Saxony, Hanover, Hessen-Kassel, Nassau, Frankfurt and the Grand-Ducal Hessian province of Upper Hesse. After the fighting ended, Prussia occupied Reuss of the older line and Saxony-Meiningen. Except for Holstein administered by Austria, these states were all Austrian allies in northern Germany.

In the occupied territories, ministers were dismissed or retired. The same was true of diplomats and consuls, although their salaries continued to be paid. The state parliaments in Hanover and Nassau had been dissolved before the Prussian occupation. The state parliament of Kurhessen was not convened by the occupying power, but the city council of Frankfurt, which accepted its conversion into a purely communal body in advance obedience. Bismarck generally did not seek to legitimize the occupation through local parliaments.

At first the commanders of the Prussian troops who had conquered the country ruled. Then came military governors (in the kingdoms general governors), at whose side civil commissioners were placed. This took over the administration. In Holstein, however, the new head of the state administration was already named Oberpräsident , that was the title in the Prussian provinces.

Newspapers were monitored; the Hessenzeitung had to stop its publication. The crew was paid for from confiscated state assets. The vast majority of administrative employees stayed in office out of a sense of duty.

Hanover

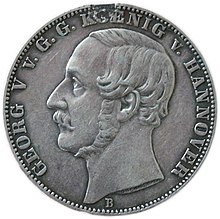

The Electorate of Hanover was restored and enlarged as a kingdom at the Congress of Vienna. After the death of the Anglo-Hanoverian monarch William IV in 1837, Queen Victoria came to the English throne and Ernst August to the Hanoverian. King Ernst August abolished the 1833 constitution. In the revolutionary year of 1848 he had to set it up again. His son George V also tried in 1855 to bring the government under the control of the nobility. The Kingdom of Hanover had an important position as a medium-sized state in the German Confederation and was able to avert membership of the Zollverein by 1851 .

In the spring of 1866 Hanover remained neutral. The king was sure that Hanover could only lose a war against Prussia. On June 13th it still allowed Prussian troops to march through. On June 15, Prussia issued an ultimatum for an alliance that was rejected by Hanover: The king wanted to maintain his sovereignty in full and not a federal reform. Therefore he chose the Austrian side and thus the status quo in Germany. The alliance with Prussia would have been the lower risk, because even if Austria had won, Hanover's existence would hardly have been in danger. The Hanoverian army finally had to capitulate on June 29th, when the capital Hanover was already occupied by Prussia.

In July, after Vogel von Falckenstein, Konstantin von Voigts-Rhetz, Chief of Staff of the 1st Army, became the new military commander in Hanover. As a civilian, District Administrator Hans von Hardenberg was placed at his side.

Especially the integration of Hanover into Prussia worried Bismarck. Civil Commissioner Hans von Hardenberg thought the Hanoverians were less sociable than the Saxons in the areas that came to Prussia in 1815. They have a strong national feeling, not just simply hatred of Prussia. Before the announcement that Hanover was to be annexed, Hardenberg took over the police force and had the Prussian garrisons reinforced in all major cities.

King George V refused to recognize his depossession while in exile in Austria . He even formed a Welfish Legion to fight Prussia. On September 29, 1867 he concluded a treaty with Prussia. Although he did not renounce the throne, he transferred 19 million thalers that he had brought to Great Britain. In return, Georg received the Calenberg domain, Herrenhausen Palace in Hanover and an annual pension. Georg wanted to continue to restore the Kingdom of Hanover; In 1868 Prussia therefore confiscated money that flowed into the so-called Welfenfonds .

Kurhessen

In the Electorate of Hesse, also known as Kurhessen or Hessen-Kassel, a liberal constitution was abolished twice and re-established twice. The country wavered between renewal and the sharp reaction of Elector Friedrich Wilhelm I , who had turned all sections of the people against him. People looked to Prussia for redemption.

In 1866 the elector feared an internal uprising more than the Prussians and would have preferred to stand aside while Austria would defeat Prussia. With his troops , even when the army was mobilized , he only wanted to defend his own country. He was outraged when Bismarck wanted to win him over to an alliance on June 15: In the event of a Prussian victory, Hessen-Kassel would get territories from Hessen-Darmstadt. The state parliament, however, wanted Hessen-Kassel to remain neutral. Even the Minister of War asked for his release, but he was talked out of it. Prussian troops marched into Kassel on June 19 without a shot, with a basically friendly population. The elector had refused to flee and was the only sovereign to be taken prisoner by Prussia. His army was only involved in a single battle and killed four people. The commander of the Prussian 1st Army Corps, Karl von Werder, and the Cologne District President Eduard von Möller took over the governorship in Kurhessen.

In Kurhessen the situation for Prussia was more relaxed than elsewhere, because of the previous demoralization in the country. Eduard von Möller saw the opposition at best as a group of strictly Protestant clergy. He opened electoral art collections and parks to the public and recommended that tax increases should only be introduced gradually. The Hessian military was returned from Mainz at the end of August and received with all honors. Kurhessen was the first annexed area that could be completely returned to civil administration.

The former elector soon also renounced his claims. In a contract dated September 17, 1866, when he was still a prisoner in Stettin, he received the usufruct of his fideicommissarian property. He also received the annual court grant of 300,000 thalers. In return, he released the subjects, officials and soldiers from their oath of loyalty to him the next day. Two years later, however, he wanted to restore his old rule, inspired by the Hanover example. The legitimate head of the House of Hessen-Kassel and potential heir to the throne, the Prussian general Friedrich Wilhelm von Hessen-Kassel zu Rumpenheim , recognized the annexation in 1873.

Nassau

Nassau was a product of the French era : Napoleon had created a duchy from over twenty territories in 1806. The dukes gave Nassau a constitution in 1814 and, at least on paper, advanced administration and social benefits. However, this was overshadowed by numerous political conflicts and the fact that a large part of the ducal domains was beyond the budgetary authority of the state parliament.

Duke Adolph von Nassau supported the Austrian side with commitment and mobilized the troops in May 1866 . They marched across the country to face actual or imagined Prussian invasions. On June 13, the second chamber of the state parliament refused to give its approval to the campaign. The chamber gave the economic dependence on Prussia and the Zollverein as a motive. After the defeat of Austria and Bavaria near Aschaffenburg, the Duke fled to Würzburg in Bavaria, and on July 18, Prussia occupied the Nassau capital of Wiesbaden.

Nassau and Frankfurt were placed under a common civil commissioner, Gustav von Diest, the Wetzlar district administrator. General Julius von Roeder became the military commander. The Prussian District Administrator Guido von Madai ruled over the former Free City. Robert von Patow, a former Prussian finance minister, became civil commissioner for the entire occupied Main region in August 1866.

In Nassau, incorporation into Prussia met with great approval. However, Gustav von Diest had to deal with the upheavals in Nassau politics and society. The Nassauer expected a change of course in the princely domains, Catholics mistrusted the Prussian Protestants. The devout Protestant Diest consciously reinforced the occupation with Catholic soldiers from the Prussian Rhineland. However, in many places they got into disputes with the Nassau soldiers, who also returned from Bavaria in August.

On September 18, 1866, Duke Adolph released his subjects, officials and soldiers from the oath of allegiance, thereby securing property and income for the dynasty. After long negotiations, Prussia agreed and Adolph an agreement dated September 28, 1867 to a severance payment consisting of 15 million guilders, interest bearing at 4.5%, and four locks (the Schloss Biebrich , Weilburg Castle , hunting seat plate and the Luxembourg Palace in Königstein) existed. In 1890 he inherited the throne of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg after the Dutch King William III. died without male offspring.

Frankfurt

The Free City of Frankfurt was a former Free Imperial City and thus (together with the North German Hanseatic cities) an anachronism in the German Confederation. The German Bundestag had its seat in Frankfurt since 1815. As recently as 1865, the city demonstrated its independent thinking when it allowed a German parliamentary assembly - against the demands of Austria and Prussia. It is said that because of such thinking, Bismarck wanted to use the next best opportunity to end Frankfurt's independence.

The Frankfurters had little love for Prussia, but were also not enthusiastic about Austria's war. On July 14th, the Bundestag fled to Augsburg, along with the local troops with the exception of the line battalion, the regular Frankfurt military. Two days later the Prussian Main Army marched into the undefended city.

Little Frankfurt with its 90,000 inhabitants suffered most from the Prussian occupation. The city immediately had to pay 5.8 million guilders as a contribution , which was sufficient for the maintenance of the entire Main Army for a year, and also to provide quarters and forage for 25,000 soldiers. Private riding horses were confiscated, the Frankfurt newspapers were banned from appearing, the constitutional organs suspended and the Free City placed under military administration.

On July 20, the Prussian commander Edwin von Manteuffel demanded a second contribution of 25 million guilders, more than the income of a whole year, which the 8,000 taxable citizens should immediately raise. The mayors Fellner and Müller were forcibly sworn in as Prussian government representatives on July 22nd. In the Senate of the Free City of Frankfurt they pleaded for a voluntary affiliation to Prussia and for the new contribution to be paid, but the Legislative Assembly and the Permanent Citizens' Representation rejected it on July 23. The Prussian city commandant, Major General von Röder, interpreted this as an open rebellion and asked Fellner to publish a proscription list with the names and ownership of all members of the city bodies by the next morning. Otherwise he threatened to bomb and pillage the city. Bismarck ordered that all communications and traffic routes be closed if necessary until payment was made.

In this situation Fellner saw no way out and hanged himself on the morning of July 24th. As a result, not least because of the presence of foreign diplomats, the worst reprisals were relaxed. However, the city continued to suffer from the sloppy discipline of Prussian soldiers. Officers rode their horses over the graves of the main cemetery. People were attacked on the street, and if you wanted to leave the city in a carriage, your horses were taken away.

At the end of July, Mayor Müller managed to postpone the contribution from Bismarck, but received the news that the annexation of Frankfurt was imminent. On July 28th, Prussia established a civil administration. The city was divided into seven quarters, each with a military and civil commissioner. Federal institutions and the Thurn-und-Taxis'sche Post were closed. Patricians fled the city, whose debts rose by 60 percent. A petition signed by 3,300 Frankfurters did nothing. Why Prussia treated little Frankfurt so humiliatingly that even some Prussian members of the state parliament protested remains a secret to historians, says Hans A. Schmitt.

Ernst Rudolf Huber, on the other hand, sees only a certain "roughness" in Prussian behavior. The complaints were factually exaggerated. If, for example, two senators were arrested who had insisted on the sovereignty of the Frankfurt Senate, this would be covered by international law. The Senate could be compared to a deposed prince, like the Elector of Hesse. The rest of the Senate agreed to continue working as city magistrate.

In the negotiations on the new municipal constitution, which was passed in 1867, the city representatives did not succeed in preserving essential elements of the old constitution; only in the court organization and the church constitution were free urban traditions preserved. In March 1869 the Frankfurt Trial was agreed, a division of the Free City's assets into municipal and state shares. Among other things, the Prussian state took over the Frankfurt debt and thus ultimately also the payment obligation for its own contribution claim.

Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg

The acquisition of the so-called Elbe Duchies of Schleswig , Holstein and Lauenburg was more complicated than that of the other four countries. Until the German-Danish War in 1864, Schleswig was a fiefdom of Denmark outside the Confederation. Holstein and Lauenburg, on the other hand, were member states. The duchies were ruled by the Danish king in his respective function as duke. With the emergence of national liberal movements in Europe in the 1840s, there was also a (constitutional) conflict in the entire Danish state between German and Danish national liberals , which particularly emerged over the question of the national affiliation of the mixed-language Duchy of Schleswig. This resulted in a three-year war between 1848 and 1851 as part of the Schleswig-Holstein uprising .

In the German-Danish War of 1864 Austria and Prussia defeated Denmark. Together they received the rights to the duchies and initially managed them together as a condominium. Then, in the Gastein Convention of August 1865, they agreed on an administrative division: Prussia administered Schleswig, while Austria administered Holstein. Their common rule persisted. Prussia started the German War in June 1866 when its troops marched into Holstein. After the war, Austria ceded its rights to Prussia in the Peace of Prague. In 1867, Prussia formed the new Prussian province of Schleswig-Holstein from Schleswig and Holstein .

The Duchy of Lauenburg, which was also ceded by Denmark to Austria and Prussia in 1864, was a special case. In the Gastein Convention of August 14, 1865, Austria sold its claims to Prussia. At first the Prussian king ruled there only through personal union and also assumed the title of duke. Only on June 23, 1876, a law followed that incorporated Lauenburg into Prussia. Since then, the Duchy of Lauenburg has belonged to the province of Schleswig-Holstein.

A deposed prince in 1866 was also Hereditary Prince Friedrich von Augustenburg . Prussia had pushed aside its claims in the complicated Schleswig-Holstein question of inheritance. He safeguarded his rights, but released the inhabitants from the vows made to him so that they would not suffer a conflict of conscience, and did not actively try to initiate his rule. The reconciliation with Prussia took place in 1880, when Friedrich, shortly before his death, allowed his daughter Auguste Viktoria to marry the imperial grandson.

Prussian territorial losses

On February 23, 1867, Prussia and the Grand Duchy of Oldenburg signed the Kiel Treaty . As a result, the Oldenburg Principality of Lübeck received some areas of the former Duchy of Holstein with a total of 12,548 inhabitants (December 3, 1867). It was about the Ahrensbök office without the village of Travenhorst , the so-called Lübschen estates Dunkelsdorf, Eckhorst, Mori, Großsteinrade and Stockelsdorf, the so-called Lübische Stadtstiftsdörfer Böbs with Schwinkenrade and Schwochel and the Dieksee .

When Nassau and Frankfurt were incorporated into Prussia, the Grand Duchy of Hesse received an area from Nassau that had 2,312 inhabitants (1864), and from Frankfurt the villages of Dortelweil and Nieder-Erlenbach with a total of 1,267 inhabitants (1864).

Classification and outlook

The annexations of 1866 were satisfactory from a Prussian point of view. No European coalition was formed to save the old world ruled by Austria. Crowned heads were dethroned, but that was not the case with the beheading of Louis XVI. comparable in the French Revolution . Bismarck's reform plan with a national parliament found the approval of most politically thinking Germans, even if they mistrusted the author. The dynasties of Hessen-Kassel and Nassau did not hold out their resistance for long, and the efforts of the Hanoverian ex-king were ineffective.

Nowhere was Prussian rule in serious danger. With the exception of Frankfurt, Prussia had prevailed with confidence and without arbitrary harassment. The new subjects were both confused and reassured by the rapid submission. Hans A. Schmitt: "The collapse of the German Confederation was a bigger surprise than we can imagine a century later." From 1815 to 1866, the princes of Hanover and Nassau did not manage to gain the affection of their then newly won subjects . The subjects seemed to see their fatherland where they were doing well.

During the war against Denmark, the liberals in Prussia had doubts whether freedom would be possible without unity, says Heinrich August Winkler . "The Prussian annexations in northern Germany were, seen in this way, almost an anticipation of the freedom of the whole of Germany." At first the liberals feared centralization, bureaucracy and military burdens, but soon the situation would ease. The "old Prussian one-sidedness", said the National-Zeitung in June 1866, would be "overcome by the entry of new living elements [...]".

Prussia already had a great influence on the remaining states of northern and central Germany, also in economic terms. Many had contractually subordinated their military to the Prussian army. By an alliance dated August 18, 1866 , they committed to mutual assistance and the establishment of a common federal state. This North German Confederation received its constitution on July 1, 1867. As a result of the annexations in the previous year, eighty percent of federal residents lived in Prussia.

literature

- Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316-347

supporting documents

- ↑ Pierer's Universal Lexikon , Volume 15. Altenburg 1862, pp. 253-254.

- ^ Pierer's Universal-Lexikon , Volume 8. Altenburg 1859, pp. 485-486.

- ^ Peace treaty printed by: Ernst Rudolf Huber: Documents on German Constitutional History 2 = German Constitutional Documents 1851–1900. 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1986. ISBN 3-17-001845-0 , No. 192, pp. 260ff.

- ^ Peace treaty printed by: Ernst Rudolf Huber: Documents on German Constitutional History 2 = German Constitutional Documents 1851–1900. 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1986. ISBN 3-17-001845-0 , No. 189, pp. 256ff.

- ↑ Figures from: Antje Kraus: Sources for the population statistics of Germany 1815–1875. Hans Boldt Verlag, Boppard am Rhein 1980 (Wolfgang Köllmann (Ed.): Sources for population, social and economic statistics in Germany 1815-1875 . Volume I).

- ↑ http://webmap.geoinform.fh-mainz.de/hgisg/multi4/buttonsTempl.php?bildPfad=statistik/BevHEH-otal.htm&isNoImage=1

- ^ Jürgen Angelow: From Vienna to Königgrätz. The Security Policy of the German Confederation in European Equilibrium (1815–1866) . R. Oldenbourg Verlag: München 1996, p. 252.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316–347, here p. 328.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, pp. 558, pp. 581/582.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316–347, here pp. 329/330.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 487.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, p. 577.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 488.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, pp. 489/491.

- ^ Friedrich Thimme: Wilhelm I., Bismarck and the origin of the annexation thought 1866. In: Historische Zeitschrift , Munich: Cotta [later:] Oldenbourg, Volume 89 (1902), pp. 401–457, here pp. 404/409.

- ^ Friedrich Thimme: Wilhelm I., Bismarck and the origin of the annexation thought 1866. In: Historische Zeitschrift , Munich: Cotta [later:] Oldenbourg, Volume 89 (1902), pp. 401–457, here pp. 405–407, p 415, p. 418.

- ↑ See Thoughts and Memories , Chapter 20, III-V; Chapter 21, VI. Project Gutenberg ,

- ↑ Christoph Nonn: Bismarck. A Prussian and his century . Beck, Munich 2015, p. 171.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316–347, here p. 330.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, p. 582.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, pp. 582/583.

- ↑ Eberhard Kolb: Russia and the founding of the North German Confederation . In: Richard Dietrich (ed.): Europe and the North German Confederation . Berlin: Haude and Spenersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1968, pp. 183–220, here p. 196.

- ↑ Eberhard Kolb: Russia and the founding of the North German Confederation . In: Richard Dietrich (ed.): Europe and the North German Confederation . Berlin: Haude and Spenersche Verlagbuchhandlung, 1968, pp. 183–220, here pp. 198/199.

- ↑ Eberhard Kolb: Russia and the founding of the North German Confederation . In: Richard Dietrich (ed.): Europe and the North German Confederation . Berlin: Haude and Spenersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1968, pp. 183–220, here p. 203.

- ↑ Eberhard Kolb: Russia and the founding of the North German Confederation . In: Richard Dietrich (ed.): Europe and the North German Confederation . Berlin: Haude and Spenersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1968, pp. 183–220, here p. 203.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, p. 575.

- ↑ Christoph Nonn: Bismarck. A Prussian and his century . Beck, Munich 2015, p. 172.

- ↑ Eberhard Kolb: Russia and the founding of the North German Confederation . In: Richard Dietrich (ed.): Europe and the North German Confederation . Berlin: Haude and Spenersche Verlagbuchhandlung, 1968, pp. 183–220, here pp. 210–212.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, pp. 583/584.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, p. 584.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, pp. 584/585.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, p. 600.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, p. 599.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, p. 585.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, p. 558, p. 586.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, p. 578.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316-347, here pp. 332-334.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, pp. 578/579.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316-347, here pp. 332/333.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316–347, here pp. 318 f.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316-347, here pp. 321-323.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316–347, here p. 332.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316-347, here pp. 335/336.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, pp. 558, pp. 586-588.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316–347, here pp. 317/318.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316-347, here pp. 323-325.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316–347, here p. 332.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316–347, here p. 336.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, pp. 558, p. 592.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316–347, here pp. 316/317.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316-347, here pp. 326/327.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316–347, here p. 332.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316–347, here p. 337.

- ↑ Andreas Anderhub: Administration in the Wiesbaden district 1866–1885, 1977, page 39

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, pp. 558, p. 593.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316–347, here p. 320.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316-347, here pp. 325/326.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316–347, here p. 338.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316–347, here p. 339.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316-347, here pp. 339/340.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, pp. 594/595.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, p. 509, footnote 101.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, pp. 558, p. 595.

- ^ Antje Kraus: Sources for the population statistics of Germany 1815–1875 . Hans Boldt Verlag, Boppard am Rhein 1980 (Wolfgang Köllmann (Hrsg.): Sources for Population, Social and Economic Statistics in Germany 1815–1875 . Volume I), p. 123.

- ^ Antje Kraus: Sources for the population statistics of Germany 1815–1875. Hans Boldt Verlag, Boppard am Rhein 1980 (Wolfgang Köllmann (Hrsg.): Sources for Population, Social and Economic Statistics in Germany 1815–1875 . Volume I), p. 135, p. 141.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316–347, here p. 346.

- ^ Hans A. Schmitt: Prussia's Last Fling: The Annexation of Hanover, Hesse, Frankfurt, and Nassau, June 15 – October 8, 1866 . In: Central European History , Volume 8, Number 4 (December 1975), pp. 316-347, here pp. 346/347.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: The long way to the west , Volume 1, Bonn 2002, p. 180. There also the quote.