Dissolution of the German Confederation

The dissolution of the German Confederation was discussed several times during the existence of this confederation . The constitutional laws of the federation did not provide for any dissolution, nor for members to leave it.

In the years 1848 and 1849 a revolutionary German Empire came into being in the area of the German Confederation . But even during this time the Bund was not dissolved: The Bundestag (the only federal organ) only stopped its "previous" activities in favor of the Reich Government . In 1851 the covenant was restored to its old form , and a period of almost ten years of reaction began. Especially after 1859 there was again a debate about federal reform .

The German Confederation was finally dissolved in the summer of 1866. Prussia claimed that the Confederation had already been dissolved by the federal decree of June 14th . The Bundestag had accepted a motion contrary to the federal government to mobilize the federal army against Prussia. The remaining member states like Austria denied this view.

However, Prussia and its allies triumphed in the German War of June and July 1866. In the peace treaties with the war opponents, Prussia recognized that the German Confederation had been dissolved. On August 24, 1866, the Bundestag confirmed the dissolution. The federal government did not have a successor in the legal sense. In the north of his former territory, however, a Prussian-led federal state emerged , the North German Confederation .

Solvability

The Federal Act of 1815 stated:

“Article 1. German Confederation. The sovereign princes and free cities of Germany [...] unite to form a permanent league, which is to be called the German Confederation. "

The Vienna Final Act of 1820 stated:

“Article V. The federation is founded as an indissoluble association, and no member of it can therefore leave this association freely.

Article VI. According to its original provision, the Federation is limited to the states currently participating in it. The admission of a new member can only take place if the entirety of the members of the Confederation finds them compatible with the existing conditions and appropriate to the benefit of the whole. Changes in the current holdings of the federal members cannot bring about changes in the rights and obligations of the same in relation to the federal government without the express consent of the whole. [...] "

In summary, the federal constitutional laws determined:

- no dissolution of the federal government or termination of the federal treaty,

- no exit of a member state,

- no exclusion of a member state,

- no admission of new member states without the consent of all.

- If a member state wanted to cede territories to a foreign state that did not belong to the federal government, this required the consent of all member states.

A secondary aspect was whether only the member states could decide on reform or dissolution. The federal act that established the federation was part of the Vienna Congress Act. This, however, had been signed by other states, major European powers. The non-German great powers Great Britain , France and Russia claimed a “guarantee right” for the treaties, in other words: They saw for themselves a veto right against constitutional changes. Austria, Prussia and the other German states in turn vehemently contradicted this.

The Bundestag, the only federal organ, could and had to force the member states to adhere to the constitutional laws. This also included the guarantee for the preservation of the federal government and the federal territory. The ultimate measure of the federal government was federal execution , an emergency military action directed against the government of a member state.

Continuity in the Revolution 1848–1851

In March 1848 riot forced the member states to deal with reforms of the German Confederation. The newly appointed representatives to the Bundestag, for example, abolished censorship and set up the Committee of Seventeen , which already presented a draft constitution for a German Reich . The further development, however, took place via the German National Assembly . It had been elected by the people on the basis of federal resolutions over the member states.

In June / July 1848 the National Assembly set up a provisional central power (Reich government). The Bundestag then transferred its powers to the Reich government. The majority of the National Assembly saw revolutionary organs in the National Assembly and the Reich government. They drew their legitimacy from the will of the people. In fact, the Bundestag had only approved these organs because of popular anger.

However, one could see the German Reich that was emerging as a continuation of the German Confederation. According to this point of view, the German Confederation had received a new name and new organs. When the conservative forces slowly regained the upper hand in the fall of 1848, the National Assembly began to see the Reich in the continuity of the Confederation. That was also helpful in trying to get recognition from abroad.

In the spring of 1849 Prussia and other states illegally dissolved the National Assembly and the revolution was violently suppressed. The Reich government, however, was never officially questioned and in December 1849 transferred its powers to a federal central commission . It turned out to be significant that the Bundestag resolution of July 1848 had not dissolved the Bund, which the Bundestag was not even allowed to do.

Prussia did not yet want to recognize the Bundestag as restored and capable of acting, since it was pursuing its own attempt at unification with the Erfurt Union . The Prussian politician Joseph von Radowitz adopted the idea of a double federation , as had already been designed by Heinrich von Gagern : A Prussian-led federal state should be linked to Austria via another federation (which would have corresponded to the German Confederation). After the autumn crisis of 1850 , however, Prussia had to give way to Austria.

Dissolution in 1866

Prussia's federal reform plan and the mobilization of the federal government

At the end of the 1850s the rivalry between Austria and Prussia resurfaced and a new reform debate arose. For a short time both great powers worked together in the war against Denmark in 1864, but soon fell out over the future of Schleswig and Holstein. Prussia wanted to annex these two duchies wrested from Denmark .

During this time, the Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck tried to draw the public's attention to the reform question. On June 10, 1866, he presented proposals for federal reform that would have turned the German Confederation into a small German nation-state . This state would have had a parliament and “federal authority” (which could be understood as a government). Austria and the areas under the Dutch king ( Limburg and Luxembourg ) no longer belonged to the reformed German Confederation. This reform plan eventually became Bismarck's war program.

Prussian troops finally marched into Holstein administered by Austria in June 1866 because Austria is said to have violated Prussian rights. Thereupon Austria applied in the Bundestag to mobilize the armed forces against Prussia. Austria received a majority for this on June 14th .

Prussia interpreted the decision as a federally illegal declaration of war against a member state. In fact, due to lack of time, Austria did not take the complicated route of ordinary federal execution. Prussia concluded that the unlawful decision made the federal government cease to exist. But the basis of the German nation still exists. On this basis and on its reform plan, Prussia wanted to found a new federation with the other willing member states. It reserved its claims to the federal liquidation estate. Immediately after the decision, the German War began.

Waste from the federal government

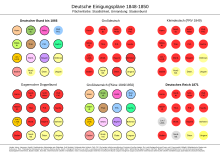

Seventeen German states sided with Prussia during the war and thus against their federal obligations:

- From June 19 to June 30 (before the Battle of Königgrätz ) Oldenburg , Lippe , Saxe-Coburg , Saxe-Altenburg , Schwarzburg-Sondershausen , Waldeck , Anhalt , Mecklenburg-Schwerin

- Then from July 4th to 6th it was Bremen, Lübeck, Hamburg, Schaumburg-Lippe , Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt , Reuss younger line , Saxony-Weimar, Mecklenburg-Strelitz and Braunschweig.

If the Bundestag had had the strength to do so, it could have acted against these states as well as against Prussia. Some delayed mobilization, and Braunschweig was able to avoid this entirely. According to their self-image, they have not necessarily renounced the German Bund, even if they withdrew their envoys from the Bundestag. On June 16, the representative from Luxembourg-Limburg saw the Bundestag no longer having a quorum, but insisted on the continued existence of the Federation. Despite the different forms of withdrawal, it became clear that “the German Confederation was in full dissolution” (Huber).

At the end of July, Austria's allies withdrew and left. Sachsen-Meiningen definitely dismissed its Bundestag envoy (July 26th), Baden withdrew its troops from the federal contingent and (August 2nd) declared the federation dissolved, Reuss older line withdrew from the federation (August 9th), Luxembourg withdrew its envoy back (August 10), as well as Frankfurt (August 16). In the end there were still members: Austria, Bavaria, Saxony, Württemberg, Hanover, Grand Duchy of Hesse, Kurhessen, Nassau, Liechtenstein and (originally controlled by Austria) Holstein.

Dissolution and liquidation

On July 28, 1866, a preliminary peace between Austria and Prussia came into force, which anticipated the most important points of the later peace agreement. In this preliminary peace in Nikolsburg , Austria recognized the dissolution of the German Confederation. Prussia was allowed to rearrange Germany north of the Main . Furthermore, Austria was spared and kept all of its territories except for Veneto. In the Peace of Prague on August 23, Austria repeated the recognition of the dissolution.

Nevertheless, a session of the Bundestag took place in Augsburg on August 24th, in the dining room of the hotel "Drei Mohren" . The remaining nine governments were represented. According to the protocol, the Bundestag ended its activities "after the German Confederation is to be regarded as dissolved as a result of the war and the peace negotiations." Despite the unanimity principle, there was no vote. Prussia had previously signed peace treaties with the recognition of the dissolution with Württemberg, Baden and Bavaria, and only later with the other war opponents.

This did not determine exactly when the covenant was dissolved. This question was important for the Prussian annexation of four war opponents , Hanover, Kurhessen, Nassau and Frankfurt. According to the Prussian view, the federal government no longer existed since the federal decree of June 14th. The occupation and then annexation of these four states therefore took place solely within the framework of international law, which at the time allowed the annexation of war opponents. But if one follows the opposite view that the federation continued to exist during the war, then one can criticize that the four states were not involved in the dissolution of the federation. In addition, they had not signed any peace treaties with corresponding clauses.

The Peace of Prague regulated what should become of the property of the German Confederation. Austria retained its shares in federal assets and the property from the federal fortresses. The officials were guaranteed their pensions.

The major European powers had reserved the right to reject changes to the federal constitution. In 1866 such contradiction did not arise, unlike in 1849/50; Bismarck had even agreed in advance with France the most important provisions of the Peace of Prague, such as the Main Line. In 1867 the Luxembourg crisis broke out , as a result of which the great powers recognized Luxembourg's independence and neutrality. On this occasion they also established (Article 6 of the London Agreement ) the dissolution of the German Confederation.

Succession

There was no official successor organization for the German Confederation. In the Peace of Prague, however, ways were described what could become of the previous member states:

- North of the Main Line, Prussia was allowed to annex territories and "establish a closer federal relationship [...]". With the North German Confederation , a federal state, Prussia implemented its federal reform plan in at least one part of Germany.

- The states in southern Germany (Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden and Hessen-Darmstadt) were free to found a southern German confederation . This confederation was also allowed to enter into an alliance with the north. The southern alliance did not come about. Instead, the southern German states concluded the so-called protective and defensive alliances with Prussia. This gave them the military protection that the German Confederation had previously granted them. In the event of war, the Prussian king became the commander-in-chief of their armies.

Even if the North German Confederation was not the successor to the German Confederation, the prehistory of the German Confederation was of great importance for the foundation of the state in 1866/1867. One of the many links between the German Confederation and the North German Confederation or German Empire was primarily the Bundesrat , which was modeled on the Bundestag. In Article 6, the North German Federal Constitution even explicitly refers to the earlier distribution of votes in the Bundestag.

rating

In 1865, the war between Austria and Prussia was “by no means necessarily inevitable”, said Jürgen Angelow . According to the provisional settlement of the Schleswig-Holstein question in the Gastein Treaty , a settlement would have been possible if the two great powers had shared leadership and spheres of influence in Germany. At that time there was still a lack of public willingness to go to war and foreign policy security for Prussia for a small German solution without Austria.

In the period after the revolution from 1851 onwards, Austria wanted to act from a position of strength again, while its power declined internationally (e.g. as a result of the Italian War in 1859) and the power of Prussia increased. Bismarck, with his many proposals for federal reform, tried to come to an understanding with Austria, but only if Prussian independence and his position in northern Germany were retained.

Austria also refused to make small concessions. It was concerned about its position of power in Germany and feared that while Prussia could dominate northern Germany, Austria could not dominate southern Germany with large kingdoms like Bavaria and Württemberg. Austria's claim to supremacy was neither covered by federal law nor by its objective strength. Bismarck initially achieved his minimum goal, the Prussian supremacy in all of northern Germany, but no reform of the German Confederation.

The dissolution of the German Confederation ultimately did not mean the collapse of the European security order of 1815, but only a regrouping in Central Europe. This order and balance persisted even after the so-called founding of the empire on January 1, 1871, since the German Empire (excluding Austria) was just bearable for its neighbors.

supporting documents

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume I: Reform and Restoration 1789 to 1830 . 2nd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1967, p. 588.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume I: Reform and Restoration 1789 to 1830 . 2nd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1967, pp. 675-678.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume I: Reform and Restoration 1789 to 1830 . 2nd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1967, pp. 634/635.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume I: Reform and Restoration 1789 to 1830 . 2nd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1967, pp. 536-538.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume I: Reform and Restoration 1789 to 1830 . 2nd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1967, p. 542.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm . 3. Edition. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 565/566 .

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm . 3. Edition. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 567/568 .

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm . 3. Edition. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 571, 576 .

- ↑ Christopher Clark: Prussia. Rise and fall 1600–1947 . DVA, Munich 2007, p. 624.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm . 3. Edition. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 576 .

- ^ Michael Kotulla : German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, pp. 488/489.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm . 3. Edition. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 581/582 .

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm . 3. Edition. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 577 .

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, pp. 328, 488/489.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm . 3. Edition. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 651 .

- ^ Jürgen Angelow: From Vienna to Königgrätz. The Security Policy of the German Confederation in European Equilibrium (1815–1866) . R. Oldenbourg Verlag: München 1996, pp. 236/237.

- ^ Andreas Kaernbach: Bismarck's concepts for reforming the German Confederation. On the continuity of the politics of Bismarck and Prussia on the German question. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1991, pp. 238/239.

- ^ Andreas Kaernbach: Bismarck's concepts for reforming the German Confederation. On the continuity of the politics of Bismarck and Prussia on the German question. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1991, pp. 243/244.

- ^ Andreas Kaernbach: Bismarck's concepts for reforming the German Confederation. On the continuity of the politics of Bismarck and Prussia on the German question. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1991, pp. 238, 243/244.