Reich diplomacy 1848/1849

The Empire diplomacy in the years 1848/1849 was an attempt by the then emerging German Reich to entertain, total German foreign relations with other countries. However, the larger German states did not want to give up their diplomatic services in favor of the German central authority , and the major European powers refused to officially recognize the central authority. However, it has been recognized by several smaller European countries and the USA. The attempt at Reich diplomacy was only partially successful.

Reich Foreign Ministry

The Bundestag had decided on the election of the National Assembly and had the governments of the individual states hold the elections. The Bundestag then transferred its rights to the National Assembly and also recognized the Reich Administrator. However, the situation of the Reich Ministry remained precarious: It could not exercise any direct power, had hardly any officials and was dependent on the support of the national governments. The governments gave this support at their own discretion.

According to the Central Authority Act of June 28, 1848, the Reichsverweser received executive power for the general security and welfare of Germany, the overall direction of all armed forces and represented Germany in terms of international law and trade policy. The Reich Administrator and the National Assembly decided jointly on war and peace and treaties with foreign countries. The Austrian Anton von Schmerling became Reich Minister of the Interior and Reich Minister of Foreign Affairs in a provisional rump cabinet on July 15, the latter being taken over by the new Prime Minister Karl zu Leiningen on August 5 . For reasons of proportionality, the Reichsverweser reorganized the Leiningen cabinet on August 9, with Johann Gustav Heckscher becoming Foreign Minister instead of Justice. Heckscher stayed in office until September 5th. Interior Minister Schmerling was also appointed Foreign Minister on September 17th. The new Reich Prime Minister Heinrich von Gagern took over both offices on December 17th. On May 16, 1849 August Jochmus became foreign minister in the Graevell cabinet and kept it in the Wittgenstein cabinet until the end of central power on December 20, 1849.

Like most other Reich ministries, the Foreign Ministry had to be built from nothing. At the end of August 1848, the Foreign Ministry had a Secretary of State, two registry lists and an editor. By February 15, 1849, the number of employees grew to nine, plus the diplomats.

Prerequisites for Reich diplomacy

The central authority used the thesis that the German Confederation would only be reformed and therefore no new recognition was necessary. The conversion of a confederation into a federal state or the renaming to "German Reich" was irrelevant in this view. The federal government had already had the right to decide on the Federal War and the Federal Peace and to maintain relations with other powers. This right was given to the National Assembly by the Bundestag.

However, one could also take a completely different view: the nation-state principle meant a revolutionary break against the federal government, which had expressly defended itself against this principle. Whether the other states actually wanted to recognize the central power was at their own discretion. To do this, they should have had a positive attitude towards the politics of German unification.

The major foreign powers, however, had two reasons against a German nation-state. He would have destroyed the balance of powers and affected their own supremacy. Konrad Canis: "A Greater Germany of the Paulskirche signaled a hegemonic urge to them, which could limit the continental power position especially of Russia and France, but also of England." Second, the nation-state would have been born out of the revolution and would therefore be unpredictable, like the French Revolution of 1789. The great powers were thinking of social and state upheavals as a result of new, expected crises.

As early as July 23, 1848, the provisional Reich Foreign Minister Schmerling set up a promemoria . His aim was for the Reich to maintain diplomatic relations with other countries instead of the individual German states; but Austria and Prussia should not be offended. Therefore, one should ask both great powers which ambassadors they think could be taken over by the empire. The Reichsverweser then selects the suitable ones from those who could also remain representatives of Austria or Prussia. This would make it easier for the two great powers to do without the envoys in the secondary states.

Foreign Minister Heckscher, however, changed the approach, possibly prompted by parliamentary motions from the National Assembly or the central state attitude of the Prime Minister. The exact reasons and the discussions in the Council of Ministers can no longer be determined. On August 21, Heckscher reported to the National Assembly that extraordinary Reich envoy had already been appointed to announce to foreign countries that the Reich Administrator was taking office. Viktor Freiherr von Andrian is probably already in London, Friedrich von Raumer and Karl Theodor Welcker are still on their way to Paris and Stockholm, respectively.

Great Britain, France and Russia should quickly receive imperial envoys, said Heikaus, in order to demonstrate the right to equality with these great powers under international law. As early as July 22nd, the National Assembly had requested an envoy in Paris, and the central power also hoped that the revolutionary government of the French Republic would be particularly willing to accept an envoy because it would automatically be recognized by the new German Empire. It turned out, however, that France first wanted to coordinate its behavior towards Germany with the other great powers. Leiningen and Heckscher could have known this early on.

Attitudes of the great powers and the USA

Great Britain

In Great Britain, Foreign Minister Palmerston first noted that the essential interests of his country and Germany were the same: Both had to fear an attack from Russia or France, or even both in common. England should therefore strive for close ties to a strong, liberal Germany. However, there was a trade conflict with the protectionist German customs union . The Zollverein was rightly seen in England as an obstacle to exporting to Germany; however, this export had increased despite the Zollverein. On March 23, the British Foreign Minister instructed the British plenipotentiary in Frankfurt to promote the restructuring and stability of Germany without intervening directly.

The Schleswig-Holstein question then ensured that Great Britain's sympathy for German unity cooled considerably. Palmerston was furious when the National Assembly rejected the Malmo ceasefire. But the National Assembly was dependent on public opinion and had no choice on this point: it had to stand behind the Schleswig-Holsteiners.

Heinrich von Gagern , President of the National Assembly, addressed the British government in early July. She should recognize the imperial administrator Archduke Johann, as is customary among sovereigns. This is also an encouragement for Germany, which is striving for a constitutional government. But England refused recognition for formal reasons. The Reichsverweser had been appointed by a national assembly which had not yet determined the permanent institution for the state authority of a united Germany. It remained an expression of British benevolence for the happiness of the German nation.

The German representative Andrian was welcomed in government circles in London and received on August 25th by Foreign Minister Palmerston. Formal recognition, however, continued to fail because the English government saw the central power as the legal successor to the Bundestag, but considered it uncertain whether this change would be permanent. One could therefore only give Andrian the status of an official representative.

Palmerston had preached constitutionalism since 1830, but in 1848 he feared above all a Europe-wide chaos through revolutionary violence. Law and order was a top priority for him. The Vienna Treaty of 1815 ensured a delicate European equilibrium, against the background of which Great Britain was best able to pursue its supremacy at sea. Any major shift in power on the continent would have jeopardized this position. (Only in the case of Italy did he make an exception.) The uprising in Schleswig-Holstein harbored the danger of general war in Europe, he believed.

The English royal family was pro-German, the public and the press radically pro-Danish, as Denmark was the underdog . Palmerston had to admit that some of Schleswig-Holstein's lawsuits were justified. But under the given circumstances, and because of the unrest of the Chartists in his own country, he could no longer intervene as a diplomatic measure.

France

In Germany there was a fear that the new revolutionary France might again be out for conquest. Foreign Minister Lamartine, however, appeased on March 4, 1848 that even if the republic no longer recognized the treaties of 1815, it would not seek any territorial changes without a joint agreement. With its republican form of government, France only wanted to serve Germany as a model, Lamartine wrote to the French envoy in Frankfurt. Nevertheless, in March rumors spread in southern Germany that an incursion by French troops or German and Polish workers armed by France was imminent.

The German left, however, would have liked to see a Franco-German brother pact. But all of France from left to right very soon internalized the traditional view that its security depended on the small states in Germany. Some could only imagine a German nation-state if France got the left bank of the Rhine as compensation.

The Frankfurt Reich representative Friedrich von Raumer was received accordingly coolly in Paris. France only accepted him as an officious, not as an official representative, and that was exactly how its own representative in Frankfurt saw it. When von Raumer pressed for recognition, the French government first held him out and then refused. After Louis Bonaparte had been elected President in December 1848, Frankfurt withdrew from Raumer and instructed the Baden ambassador to represent the interests of the Reich. France did not want to admit a German Empire, which led to a serious crisis in Franco-German relations. In general, France's attitude towards Germany from 1848 to 1850 was negative: nothing was done to support the revolutionary movement in 1848, nor was the establishment of a small Germany encouraged.

Russia

Even in March, no other great power had been judged so negatively by the German liberals as despotic Russia. During the revolution he was trusted to encourage the German states to counterrevolution, certain German elites were suspected of being allied with Russia, and there was speculation everywhere about a war.

As early as March 14, 1848, the Russian Tsar Nicholas I reacted to the events in Berlin with a manifesto that seemed to announce Russian intervention. After the initial anger, and under the influence of his advisors, his attitude became wait-and-see and defensive. A mere break-up of Germany into its individual parts would, in the opinion of the Russian Ambassador in Berlin, have opened the door to republican influences. These would later also reach the Russian borders. Furthermore, Prussia and Germany are to be seen as bulwarks against revolutionary France. The Tsar himself originally had greater sympathy for Prussia than for Austria; He would not have objected to a violent suppression of the revolution in Berlin.

Initially, the Reich Foreign Ministry planned to install the Prussian General Hans von Auerswald as envoy in St. Petersburg . But it was learned that the tsar had not yet recognized the French government and that difficulties were expected. According to statements by a Russian diplomat, Russia would at most want to maintain official relations with Germany. Frankfurt therefore awaited negotiations with Russia about a mere notification embassy. In September, however, it was clear that the negotiations would fail; By the way, Auerswald was killed in the September riots. Again, without success, the Reich Foreign Ministry sought a permanent Reich embassy.

Support for the uprising in Schleswig-Holstein and flirting with the German imperial crown also allowed Russia's sympathy for Prussia to cool. Finally, Russia welcomed the re-emergence of Austria, which had received a new constitution as a unitary state in the spring of 1849. After all, Russia saw it as its own best interest that Austria survive. The insurgents in northern Austria , Hungary and Transylvania would be led by Poles; the Hungarian-Polish conspiracy endangers Russia and Austria as it were.

United States of America

In the USA there was a lot of sympathy for the emerging German federal state, for which America seemed to be the model. The large number of German immigrants, almost invariably enthusiastic about the revolution, also meant important votes, and thirdly, the United States believed that a united Germany would be good for American trade interests.

Over time, however, the attitude became more negative when the pursuit of unity was unsuccessful. It was believed that the Germans were to blame for this themselves and that they were immature for liberal institutions, and that dreamers were not very practical. Despite the sympathy for the people (and hatred of the Prussian king), many Americans were hostile to the National Assembly, the press mostly pointing out its mistakes rather than the difficulties it was facing. However, in March 1849 the journalist Kendall wrote sympathetically:

"When the great Congress [d. H. the National Assembly], which is gathered in Frankfurt, [...] can unite and reconcile all the different elements that make up the immense German Confederation , then it can certainly work miracles. "

President James K. Polk appointed on 5 August 1848 in a note to Congress Andrew Jackson Donelson for Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Federal Government of Germany . The latter also remained ambassador in Berlin; Foreign Minister Buchanan instructed him to be careful that his new accreditation is not interpreted as a move against Prussia. The MP Friedrich von Rönne became the Reich's official envoy. Frankfurt and Berlin agreed that he would leave the Prussian diplomatic service and only represent the central authority in Washington. Due to difficulties on the journey, he did not arrive at his destination until January 26, 1849.

Because of its policy of neutrality, the US was generally reluctant to support the Frankfurt central authority too openly. It is true that in July 1848 the President no longer signed an extradition agreement with Prussia because a German Union would soon be established, and in August the Foreign Minister considered concluding a single trade agreement with the central authorities only. Later that year, however, he rejected the idea because the German states had not yet relinquished their power and he did not want to expose himself to the charge of undesirably interfering in German affairs. Polk's tenure was also coming to an end; Zachary Taylor's new presidency from March 1849 finally led to a complete change of course: Donelson was again ordered from Frankfurt to Berlin.

Imperial embassies and individual states

On September 20, 1848, the Reich Ministry asked the individual German states to withdraw their missions abroad. In future, only Reich delegates were to represent German interests. The new Foreign Minister Anton von Schmerling struck a very moderate tone, especially with regard to the great powers Austria and Prussia, and made the suggestion, for example, to discuss together which embassies could best be merged into imperial embassies. Prussia's representative at the Central Authority Camphausen referred to Prussia's great power status, which it wanted to use to introduce the German federal state into the European family of states. First of all, a German-Prussian agreement about Germany's future foreign relations must be established. For all its reluctance, this was a fundamental willingness on the part of Prussia to participate in the recognition of the German Reich abroad.

In October the Senate of the Free City of Frankfurt informed the Reich Foreign Minister that the city would withdraw its only diplomat, the Chargé d'affaires in Paris, who represented the four free German cities there. Württemberg withdrew his envoys from St. Petersburg, Paris, London, Brussels and The Hague, only in St. Petersburg and Paris it initially left chargé d'affaires. Nassau, Kurhessen, the Grand Duchy of Darmstadt, both Mecklenburg, Saxe-Weimar, Braunschweig and Oldenburg showed the same unconditional readiness. In addition to Württemberg, Bavaria, Saxony and Baden also showed a fundamental willingness, but wanted to wait for a joint declaration by all German states and the actual appointment of Reich envoy at the appropriate places. At this point, according to Heikaus, the development was going well for the Reich Ministry, even if it was questionable whether the medium-sized states such as Bavaria and Saxony would still be prepared to make a joint declaration after the individual states had gained strength from autumn 1848. From autumn onwards, however, the individual states were less inclined to cooperate with the central government.

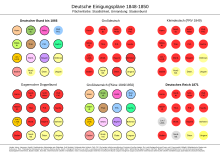

The provisional imperial power was recognized by the accreditation of an ambassador, not only from the USA but also from Sweden , the Netherlands , Belgium , Switzerland , Sardinia , Naples and Greece . Imperial ambassadors were mostly Frankfurt delegates; this tendency was intended to parliamentarize the emerging diplomatic service of the empire. However, it led to many MPs, who mostly stayed in Frankfurt, neglecting their functions as diplomats.

See also

- Provisional central power

- List of imperial and foreign envoys 1848/1849

- Foreign Policy in Germany 1848–1851

literature

- Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Dissertation Frankfurt am Main. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1997, ISBN 3-631-31389-6 .

- Günter Wollstein: The 'Greater Germany' of the Paulskirche. National goals in the bourgeois revolution of 1848/1849. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, ISBN 3-7700-0474-4 .

Web links

- List of Reich envoys and chargées , Federal Archives

supporting documents

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition. Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart u. a. 1988, p. 626.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1997, pp. 113/114.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition. Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart u. a. 1988, pp. 634/635.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Endangerment. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn a. a. 2004, p. 20.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1997, pp. 108/109, p. 147.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1997, pp. 108/109, pp. 149-151.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1997, pp. 152/153.

- ^ Werner Eugen Mosse: The European Powers and the German Question 1848-71. With Special Reference to England And Russia. University Press, Cambridge 1958, pp. 15/16.

- ^ Werner Eugen Mosse: The European Powers and the German Question 1848-71. With Special Reference to England And Russia. University Press, Cambridge 1958, p. 25.

- ^ Werner Eugen Mosse: The European Powers and the German Question 1848-71. With Special Reference to England And Russia. University Press, Cambridge 1958, pp. 22/23.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1997, pp. 158/159.

- ↑ Keith AP Sandiford: Great Britain and the Schleswig-Holstein Question 1848-64 a study in diplomacy, politics and public opinion . University of Toronto Press: Toronto / Buffalo 1975, p. 24.

- ↑ Keith AP Sandiford: Great Britain and the Schleswig-Holstein Question 1848-64 a study in diplomacy, politics and public opinion . University of Toronto Press: Toronto / Buffalo 1975, pp. 24/25.

- ^ Raymond Poidevin, Jacques Bariéty: Les relations franco-allemandes 1815–1975. Paris, Armand Colin 1977, pp. 26/27.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition. Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart u. a. 1988, p. 636.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition. Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart u. a. 1988, pp. 636/637.

- ^ Raymond Poidevin, Jacques Bariéty: Les relations franco-allemandes 1815–1975. Paris, Armand Colin 1977, p. 29.

- ↑ Manfred Kittel: Farewell to the People's Spring? National and foreign policy ideas in constitutional liberalism 1848/49. In: Historical magazine. Volume 275, Issue 2 (October 2002), pp. 333-383, here pp. 371-373.

- ^ Werner Eugen Mosse: The European Powers and the German Question 1848-71. With Special Reference to England And Russia. University Press, Cambridge 1958, p. 14.

- ^ Werner Eugen Mosse: The European Powers and the German Question 1848-71. With Special Reference to England And Russia. University Press, Cambridge 1958, pp. 16/17.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1997, pp. 160/161.

- ^ Werner Eugen Mosse: The European Powers and the German Question 1848-71. With Special Reference to England And Russia. University Press, Cambridge 1958, pp. 26/27.

- ↑ John Gerow Gazley: American Opinion of German Unification, 1848-1871 . Diss. Columbia University, New York 1926, pp. 26, 35.

- ↑ John Gerow Gazley: American Opinion of German Unification, 1848-1871 . Diss. Columbia University, New York 1926, pp. 36, 44.

- ↑ "If the great Congress assembled at Frankfort [...] can unite and reconcile all the different elements which make up the immense confederation of Germany, they can certainly work miracles." Massachusetts Quarterly Review , March, 1849. Quoted from: John Gerow Gazley : American Opinion of German Unification, 1848-1871 . Diss. Columbia University, New York 1926, p. 44.

- ↑ John Gerow Gazley: American Opinion of German Unification, 1848-1871 . Diss. Columbia University, New York 1926, p. 24.

- ^ Henry M. Adams: Prussian-American Relations, 1775-1871 . Press of Western Reserve University, Cleveland 1960, p. 60.

- ^ Henry M. Adams: Prussian-American Relations, 1775-1871 . Press of Western Reserve University, Cleveland 1960, p. 60.

- ↑ John Gerow Gazley: American Opinion of German Unification, 1848-1871 . Diss. Columbia University, New York 1926, pp. 23, 31.

- ↑ John Gerow Gazley: American Opinion of German Unification, 1848-1871 . Diss. Columbia University, New York 1926, p. 26.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1997, pp. 267-269.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1997, pp. 270/272.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1997, p. 270.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1997, p. 272.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition. Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart u. a. 1988, p. 638.