German Empire 1848/1849

| German Empire German federal state |

|||||

| 1848-1849 | |||||

|

|||||

| Official language | German (de facto) | ||||

| Capital | Frankfurt | ||||

| Form of government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||

| Head of state |

Imperial Administrator Archduke Johann (1848–1849) |

||||

| Head of government | Reich Minister President | ||||

| founding | May 18, 1848 (first session of the National Assembly) | ||||

| independence | June 28, 1848 ( Central Power Act ) | ||||

| resolution | 1849/50: unsuccessful attempt to found a German Union. 1851: German Confederation restored |

||||

| National anthem | The German Fatherland (unofficial) | ||||

The German Empire , created in 1848/49 and only existed for a short time, was an attempt to form a German nation-state . Depending on the point of view, it was the renamed and reformed German Confederation of 1815, which was on the way from a confederation to a federal state , or a purely revolutionary re-establishment during the time of the German Revolution in 1848/49 . The first session of the Frankfurt National Assembly (May 18, 1848 in the Paulskirche) or the resolution on the Central Power Act (June 28, 1848) can be seen as the founding date .

The revolutionary German Empire of 1848/49 was recognized by several foreign states, including the USA . Within Germany, the individual states partly obeyed the laws and regulations of the central authority, in some cases long after 1849. The most visible result of the time was the imperial fleet , whose ships were sold by the German Confederation in 1852.

As a rule, the smaller individual German states supported the empire, while the unification ultimately failed because of the larger ones - especially the great powers Austria and Prussia . With the states crushing the revolution, the empire was short-lived. During May 1849, the National Assembly lost most of its members, the central power ended on December 20, 1849 in favor of the Federal Central Commission . In 1849/1850 another attempt was made with the Erfurt Union to unite Germany, but this also failed. In 1851 the German Confederation was restored. Only after the German War of 1866 did the federal government end, and the German Empire came into being in 1871 .

Designations

During the German Revolution, the German nation-state to be created was given different names. In the Central Power Act of June 28, 1848, the National Assembly speaks of a "German federal state". In Section 1 of the Reich Law on the Basic Rights of the German People of December 27, 1848, “the German Reich” appears. This is a reminiscence of the medieval Roman-German Empire , which in the 19th century was believed to be a strong state capable of acting. So it wasn't just the Frankfurt Constitution that would have established a German Empire . The idea of the succession of the Old Reich by a German nation-state with a constitution was very popular. The expression "Reich" distanced oneself from the unpopular German Confederation.

There are corresponding expressions for the organs of the state. The National Assembly still appears in the law of June 28, 1848 , but since the Imperial Law on the promulgation of the Imperial Laws and the provisions of the provisional central authority of September 27, 1848, the laws use the term Imperial Assembly . Occasionally contemporaries used the term Reichstag . The Central Power Act already set up an imperial administrator .

Constitutional classification

The statehood of the German Reich is difficult to determine, and there were also different opinions about it at the time. One direction took a positivist standpoint, which looked to what was already established law on which further development had to be based. This direction emphasized that a constitution was to be agreed with all state governments. The other direction proceeded from natural law and, derived from it, from popular sovereignty ; accordingly, the National Assembly alone had the constituent power and was entitled to decide on a constitution and to establish a provisional constitutional order.

The first direction was naturally represented by the monarchist right and in principle by the individual states, the other by the majority of the National Assembly and vehemently by the republican left. How one stood towards the German Confederation and interpreted the events since March 1848 also played a role. In practice, however, this apparently clear comparison could not always be maintained.

State and constitutional continuity

Constitutional historians have developed different concepts of what happens when a new constitution comes into force in a state. Unless the old constitution explicitly describes a way of changing the constitution, which is then followed, the question arises whether a new constitution will create a new state. According to Hans Kelsen, there is a primacy under international law with which one can normatively justify legal and state continuities. From the point of view of the constitution of a state, a new constitution is actually created with a new state based on it, but from the point of view of international law one can speak of an identity if a revolution brings about a new constitution in the same national territory.

Georg Jellinek sees the state association as a multitude of people who can adopt a new constitution at their own discretion, including through violence. The sociological assessment based on historical-political facts is important for the question of identity. The Weimar National Assembly of 1919 nevertheless assumed an identity despite the broken chain of legitimacy from empire to republic. Gerhard Anschütz commented that a revolution is usually not undertaken to destroy a state, but to replace the leading people and to change or change the constitution. This creates new constitutional law, but no new political life.

These are more modern concepts that are largely based on popular sovereignty . In the period around 1848, popular sovereignty was only unconditionally affirmed by the left. The majority in the Frankfurt National Assembly supported the constitutional monarchy with a sovereign monarch, whose power, however, is limited by a constitution and popular representation. While the conservatives often assumed that the sovereign monarch corresponded to God's will, the liberals thought more of a necessary balance between monarchs and representatives of the people, in the sense of dualism ,

Continuity to the German Confederation

The German Confederation existed since 1815. This confederation of states was recognized by the German states and internationally; he was part of the peace order after the Congress of Vienna . In modern terms, its tasks were primarily in the field of foreign and defense policy and internal security. There was a congress of envoys from the individual states called the Federal Assembly or Bundestag , but no government or representative body.

In the course of the March Revolution of 1848, the individual states, under revolutionary pressure, appointed liberal governments, which in turn sent liberal envoys to the Bundestag. The Bundestag was forced to introduce reforms and let the people elect a national assembly . This Frankfurt National Assembly was supposed to draw up a constitution for Germany “in order to bring about the German constitution between the governments and the people” (federal decision of March 30). This was "a direct cooperation between the old and the new powers", what had been achieved appeared as the will of the people, it had to be wrested from the princes, but the continuity of the constitutional development was preserved and the revolution steered into the "paths of a legitimate evolution" , says Ralf Heikaus.

The Bundestag had already decided on May 3, 1848, to set up a three-member federal directorate as the executive body of the federal government. The National Assembly then voted on June 28 instead for the newly created office of Reich Administrator and then for a Reich law on the introduction of a provisional central authority . The Reichsverweser thus received executive power for the general security and welfare of Germany, the overall direction of all armed forces, and he represented Germany in terms of international law and trade policy.

In this situation, the individual governments and the Bundestag wanted to avoid an open break with the National Assembly because they feared popular anger. Therefore, in a resolution of July 12, 1848 , the Bundestag officially recognized the Reichsverweser, assured him support and gave him the powers of the Bundestag. The Bundestag then stopped its activities, as the law of June 28 had already provided for, and definitely, not just suspensively. According to Ernst Rudolf Huber, it was therefore possible to establish a continuity, even a legal identity, between the German Confederation and the new federal state: No change of state, but only a constitutional change, the German Confederation had been renamed the German Reich .

Break in continuity

Ulrich Huber asks the question whether the Bundestag was able to transfer its powers to the Reich Administrator and whether the Bundestag had not inadmissibly expanded the federal purpose . De facto, a federation of states was supposed to be converted into a federal state, with the individual states having to participate, usually by changing their own constitutions. The provisional constitutional order with a national assembly and central power as the legislative and executive branches of a German federal state was revolutionary. The National Assembly was allowed to do this because the federal government gave it constitutional power through the federal electoral law. In this way it was able to enact a provisional constitution before the final one. Within the framework of the provisional constitutional order, it then granted itself legislative competence. Furthermore, she was also allowed to decide which subjects, in her opinion, belonged to the imperial legislative competence. In a very similar way, the Weimar National Assembly passed a law on provisional imperial power in February 1919 .

Certainly, according to Ulrich Huber, the same restriction applied to the provisional constitutional order as to the final one (the Frankfurt Imperial Constitution of March 28, 1849): It had to be agreed with the individual states . But there was a revolutionary transition period. An informal agreement was therefore sufficient for the provisional constitutional order. This understanding between the National Assembly and the governments was the agreement of the governments with the election of the Reich Administrator and then the Bundestag resolution of July 12th. The substantial core of the Bundestag resolution was the recognition of the Central Power Act of June 28, 1848. Ulrich Huber:

“By the way, none of the participating governments distanced themselves from the actions of the Bundestag and, for example, pleaded that their own Bundestag envoy had acted contrary to the instructions. None of the governments subsequently declared the effectiveness of the Reich administrator and the Reich Ministry to be illegal and usurpatory . The provisional imperial constitution was based on an agreement between the National Assembly and the governments; the external requirements that can reasonably be put into effect for such an agreement were met. "

In any case, the majority of the members of the National Assembly did not believe that the Federation and the Reich were identical. On the contrary, it just emphasized the revolutionary break with the dark past, with the system of the German Confederation, which had suppressed freedom. The federal government had also used all means to defend itself against national unity and liberal freedom.

Recognition by other states

The idea of an identity or continuity, however, was useful in contact with foreign countries: It is much easier to present yourself as the continuation of an existing state than to enforce the recognition of a new state. The central authority asserted that the foreign authority of the German Confederation was no longer in the hands of the Bundestag, but in their hands. However, other countries did not necessarily agree with this view. In spite of the “constitutional identity and continuity of the newly formed state structure in Germany”, according to Heikaus, the German statehood changed considerably. Foreign countries saw themselves in the right whether they recognized the central authority or not, depending on their own interests.

The major foreign powers, however, had two reasons to oppose a German nation-state. He would have disturbed the balance of powers and affected their own supremacy. Konrad Canis: "A Greater Germany of the Paulskirche signaled a hegemonic urge to them, which could limit the continental power position, especially of Russia and France, but also of England." Second, the nation state would have been born out of the revolution and thus unpredictable, like revolutionary France after 1789. The great powers feared social and state upheavals as a result of new crises to be expected.

Nonetheless, heikaus writes that there were extremely considerable initial successes in foreign policy that did not rule out further progress. With France and Great Britain, which adopted a wait-and-see attitude, there were at least official governmental relations. The provisional imperial power was recognized by the accreditation of an ambassador by the USA , Sweden , the Netherlands , Belgium , Switzerland , Sardinia , Naples and Greece .

The central authority urged the individual states to recall their envoys in foreign countries; that would have come close to renouncing its own status under international law . The smaller and most of the medium-sized states followed suit or promised to do so in the near future; in general, they usually had few diplomats of their own. Austria, Prussia and Hanover behaved hesitantly or negatively.

State authority

The creators of the central authority decided not to set up their own administrative substructure. In the National Assembly it was believed that one's own high moral authority among the people was sufficient, but the state stability of the old powers in the individual states was underestimated. The relative powerlessness of the central authority later became apparent.

The central power was subject to the political factors in Germany, the goodwill of the great powers and also the majorities in the National Assembly. Despite many difficulties, however, the government apparatus, which had to be built almost from nothing, proved to be impressively efficient, at least in the initial phase. The central authority demonstrated political weight in the fight against radical insurrections, sometimes together with the local authorities. However, the governments only agreed to cooperate with the central power as long as the political situation was still unstable for them.

Provisional system of government

The Bundestag had already decided on May 3, 1848, to set up a three-member federal directorate as the executive body of the federal government. It should be primarily responsible for defense and foreign affairs. The decision was not carried out, however, because the Committee of Fifties (which prepared the National Assembly) was bothered by the fact that only the governments should appoint the federal directors (one each from Austria and Prussia, and one from a Bavarian list of proposals for the Bundestag's Senate Council).

The National Assembly then passed the Central Power Act on June 28th for a single head of state. The Reichsverweser thus received the executive power for the general security and welfare of Germany, the overall direction of all armed forces and he represented Germany in international law and trade policy. The Reich Administrator and the National Assembly decided jointly on war and peace and treaties with foreign countries. In terms of a constitutional monarchy , the imperial administrator was irresponsible, but he set up an imperial ministry (a government) whose members countersigned the acts of the imperial administrator and thus assumed ministerial responsibility towards the national assembly. Without this having been expressly mentioned in the Central Power Act, the Reich Ministry resigned when it lost the confidence of the Reich Assembly. So, de facto, a parliamentary system had prevailed.

On June 29, the National Assembly elected Archduke Johann, who was popular with the people, as imperial administrator, an uncle of the Austrian emperor. The Central Power Act was flanked by a Reich law on the promulgation of the Reich laws and the provisions of the provisional central authority of September 27, 1848. Both formed the provisional constitutional order of Germany.

Imperial Constitution

The Imperial Constitution of March 28, 1849 was unilaterally put into effect by the National Assembly; since the great majority of the German states recognized it, but not the largest, it could not develop any effectiveness. The National Assembly placed imperial power in the hands of a hereditary emperor, who appointed and dismissed the ministers, comparable to the imperial administrator. Because of the election by the National Assembly, the empire of the Paulskirche had a democratic element in it, but the choice was limited - the King of Prussia was in mind - and after the election an imperial dynasty would have arisen.

Instead of the national assembly, a Reichstag should serve as parliament. This consisted of two chambers, the State House and the People's House. The members of the house of states were determined by the individual states, with the governments appointing one half and the parliaments the other half. There was universal and equal suffrage (for men) for the Volkshaus. Laws required the approval of both houses of the Reichstag and the Kaiser; however, the Reichstag was able to outvote the emperor by repeated votes within a certain period of time (so-called suspensive veto).

Reich legislation

In the opinion of the majority of ministers and the National Assembly, the Reich had legislative powers for all of Germany. Laws were passed by the National Assembly alone, possibly at the suggestion of the entire Reich Ministry. They were announced by the Reich Administrator after a period of time and published in the Reichsgesetzblatt .

With the exception of the Central Power Act and the Law Proclaiming Law, the National Assembly passed nine laws, the last two on April 12, 1849. Many dealt with the organization of the Central Power or National Assembly itself; the imperial law on the introduction of a general exchange order for Germany of November 24, 1848 dealt with a subject that was not controversial. Particularly noteworthy are the basic rights of the German people , which were promulgated as a law before the imperial constitution. The Reich legislation was precarious because the individual states (especially the larger ones) were not willing to recognize the legislative competence of the National Assembly.

Armed forces

The German Confederation was a confederation of states mainly because military power had remained with the member states, despite a federal war constitution . Therefore, "the unitarization of the military constitution", so Ernst Rudolf Huber, "was the key problem of the Frankfurt constitution". The individual states were aware of this, and Prussia in particular opposed the Frankfurt efforts. Prussia would have been ready for a unitarization (standardization) at most if its king had been appointed federal general, as Prussia had proposed earlier.

But even in the draft of the Committee of Seventeen set up by the Bundestag (May) there was no such separate federal general as commander-in-chief . The head of the empire should have command over the armed forces, because either (as some of the seventeen wished) the Prussian king became head of the empire and thus commander-in-chief anyway, or someone else became head of the empire, in which case there should not have been a competing commander-in-chief. Prussia's sympathy for a Unitarian military constitution waned and grew again around the turn of the year 1848/1849, when it became more likely that the Prussian king would become head of the empire. Just like Prussia, Austria and the medium-sized states also resisted their military sovereignty being mediated under a head of the Reich.

The members of the National Assembly had three concepts for a military constitution : the left and parts of the center (especially from southern Germany ) planned a unitary (unified) national army; the center and right center (especially from northern Germany ) a national army, which consisted of the contingents of the individual states, and the right (with some groups from the center and the left) wanted to keep the previous contingents of the individual states, with better coordination than the earlier Federal War Constitution.

The Imperial Constitution (§§ 11-19) later stated that the Imperial Army consisted of the contingents of the individual states. The decree had the imperial authority, the troops had to commit themselves in oath of the imperial head and the imperial constitution. The army organization was supposed to be uniformly regulated by the Reich, but the Reich authority only appointed the commanders of those units that comprised several contingents. The constitution left to a later law who should have the authority. The constitution thus represented a compromise between a unitarian and a federal defense constitution, but did not dare to answer the crucial question. Two years later, in the summer of 1851, the Bundestag of the renewed German Confederation determined that a constitutional oath by the troops was revolutionary.

The Central Power Act of June 28, 1848 gave the Reich Administrator Archduke Johann the "overall direction of the entire armed force". The left wanted him to set up an independent national militia, but he feared that it would develop into a civil war army of radicals. On July 16, 1848, Reich Minister of War Eduard von Peucker sent the so-called homage decree to the regional war ministries. The armies of the individual states were to pay homage to the imperial administrator in a parade. The troops should also wear the imperial colors . But only the smaller states obeyed the decree, the larger ones at least partially withdrew from it. The central authority controlled the federal troops in the federal fortresses, which, however, were also contingents of the individual states.

During the war against Denmark in particular, it became apparent how vulnerable Germany was at sea. Therefore, there was widespread enthusiasm for the fleet, which led to the National Assembly deciding to set up an imperial fleet on June 14, 1848 . In the short period of time the Reich was able to buy relatively few ships and convert them for naval warfare; the only war operation of the fleet took place in the sea battle near Heligoland on June 4, 1849. Most of the ships came into the possession of the German Confederation via the Federal Central Commission , which finally sold the ships after initial plans for a German fleet.

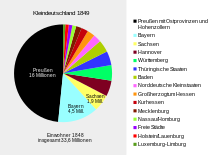

Territory and people

When determining the national territory, the National Assembly primarily proceeded from the states that already belonged to the German Confederation. However, some MPs came from areas outside the federal government, or from areas that had recently been incorporated into the federal government. In the discussions there are contributions that called for the connection of other areas such as the entire Netherlands, but these were exceptions that did not prevail. The state people consisted of the members of the states that belonged to the empire.

The delegates came to their ideas about the area of Germany on the basis of three principles. The nationality principle was based on the one hand on the German language. Second, they invoked the historical-legalistic principle according to which an area should belong to Germany if there were legal claims from ancient times. Finally, thirdly, military arguments played a role if the formation of a Polish state was rejected because it was too weak to serve as a buffer against Russia.

The constitution of March 28, 1849 referred in § 1 to the German Confederation:

- § 1. The German Reich consists of the territory of the previous German Confederation.

- The right to determine the conditions of the Duchy of Schleswig is reserved.

The following two paragraphs were particularly controversial in the constitutional discussion: If a head of state in a German country was also head of state in a non-German country, the non-German country had to have a different constitution, government and administration. A mere personal union, however, was allowed. This meant that Austria should have divided its previous national territory into a German and a non-German.

Section 87 of the constitution deals with the distribution of seats in the Reichstag house of states and names the states:

-

Kingdom of Prussia : 40 members

Kingdom of Prussia : 40 members -

Empire of Austria : 38

Empire of Austria : 38

-

Kingdom of Bavaria : 18

Kingdom of Bavaria : 18

-

Kingdom of Saxony : 10

Kingdom of Saxony : 10

-

Kingdom of Hanover : 10

Kingdom of Hanover : 10

-

Kingdom of Württemberg : 10

Kingdom of Württemberg : 10

-

Grand Duchy of Baden : 9

Grand Duchy of Baden : 9

-

Electorate of Hesse : 6

Electorate of Hesse : 6

-

People's State of Hesse : 6

People's State of Hesse : 6

-

Duchies of Holstein & Schleswig : 6

Duchies of Holstein & Schleswig : 6

-

Mecklenburg-Schwerin : 4

Mecklenburg-Schwerin : 4

-

Luxembourg & Duchy of Limburg : 3

Luxembourg & Duchy of Limburg : 3

-

Duchy of Nassau : 3

Duchy of Nassau : 3

-

Duchy of Braunschweig : 2

Duchy of Braunschweig : 2

-

Grand Duchy of Oldenburg : 2

Grand Duchy of Oldenburg : 2

-

Saxony-Weimar-Eisenach : 2

Saxony-Weimar-Eisenach : 2

-

Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha : 1

Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha : 1

-

Saxony-Meiningen-Hildburghausen : 1

Saxony-Meiningen-Hildburghausen : 1

-

Free State of Saxony-Altenburg : 1

Free State of Saxony-Altenburg : 1

-

Mecklenburg-Strelitz : 1

Mecklenburg-Strelitz : 1

-

Principality of Anhalt-Dessau : 1

Principality of Anhalt-Dessau : 1

-

Principality of Anhalt-Bernburg : 1

Principality of Anhalt-Bernburg : 1

-

Principality of Anhalt-Köthen : 1

Principality of Anhalt-Köthen : 1

-

Principality of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen : 1

Principality of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen : 1

-

Principality of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt : 1

Principality of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt : 1

-

Hohenzollern-Hechingen : 1

Hohenzollern-Hechingen : 1

-

Principality of Liechtenstein : 1

Principality of Liechtenstein : 1

-

Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen : 1

Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen : 1

-

Principality of Waldeck-Pyrmont : 1

Principality of Waldeck-Pyrmont : 1

-

Reuss older line : 1

Reuss older line : 1

-

Reuss younger line : 1

Reuss younger line : 1

-

Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe : 1

Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe : 1

-

Principality of Lippe-Detmold : 1

Principality of Lippe-Detmold : 1

-

Hessen-Homburg : 1

Hessen-Homburg : 1

-

Duchy of Saxony-Lauenburg : 1

Duchy of Saxony-Lauenburg : 1

-

Lübeck : 1

Lübeck : 1

-

Free City of Frankfurt : 1

Free City of Frankfurt : 1

-

Free Hanseatic City of Bremen : 1

Free Hanseatic City of Bremen : 1

-

Hamburg : 1

Hamburg : 1

The relatively small number of seats for Austria meant that the areas outside the old federal government (Hungary, Northern Italy) had already been factored out. It was already assumed that Austria would not accede to the constitution, but for tactical reasons a way was left open for her. This should satisfy the Greater Germans, who could only imagine Germany with Austria. Even if only the federal territories of Austria had joined the Reich, there would have been a large ethnic minority, especially the Czechs.

A Polish minority and a smaller Lithuanian minority lived in Prussia. The corresponding areas were still outside the federal government before 1848, and it was not until the March Revolution that the Bundestag decided that the province of Prussia should join the federal government. The province of Poznan with a Polish majority was divided and remained a matter of dispute . Luxembourg had the Dutch King as Grand Duke, while the Duchy of Limburg was even a Dutch province, i.e. an integral part of the Netherlands. These areas also became a matter of dispute.

The duchies of Schleswig and Holstein in personal union had the Danish king as duke, with Holstein also being a member of the German Confederation (and a Roman-German fiefdom until 1806), while Schleswig was a Danish fiefdom. While Holstein was linguistically and culturally (Low) German, German , Danish and North Frisian were widespread in Schleswig . At the same time, in parts of Schleswig there was a language change from Danish and North Frisian to German in the 19th century . In April 1848 there had been an uprising in both duchies that led to the formation of a provisional German-minded government that wanted to unite Schleswig and Holstein and join a German confederation. This was opposed by the Danish National Liberals, who wanted to integrate Schleswig into the Kingdom of Denmark while surrendering Holstein. Prussia, other states as well as the central power temporarily waged war against Denmark or supported the German insurgents diplomatically. The Schleswig-Holstein question (and in particular the question of Schleswig's national affiliation) developed into the central foreign policy problem of the Paulskirche. Both the German imperial constitution and the Basic Law of Denmark passed in June 1849 left the national affiliation of Schleswig open. Interestingly enough, Section 87 of the Reich Constitution does refer to the reservation in Section 1, but the Reich Election Act of April 12 already treats Schleswig as an integrated part of the Reich.

Symbols

The colors black, red and gold appeared as German colors as early as March , and some of them could be interpreted into depictions of the Middle Ages. In the revolutionary time from March 1848 they became generally accepted, on March 9, 1848 there was a federal decree on this. The National Assembly passed an imperial law on a German war and trade flag on July 31, 1848 , but the imperial administrator did not issue it until November 12. The colors remained in official use until the Reichsflotte was dissolved in 1852, and the black, red and gold flag waved again in 1863 for the Frankfurt Princes' Day at the Frankfurt Federal Palace .

The Bundestag and then the central power had failed to officially display the colors black, red and gold to the foreign powers. In May 1849 a British ship did not greet the German flag in the port of Kiel, in June the British commander of Heligoland fired a warning shot on German warships of the Imperial Fleet . Only then did the central authority try to file a complaint; By May 1850, the Federal Central Commission achieved the recognition of essentially those states that had also recognized central power (including France). Great Britain and Russia decided to permanently refuse recognition because the situation in Germany was unclear. According to the British view, ships under black, red and gold sailed as pirate ships. Ernst Rudolf Huber:

“This English discrimination against the colors of the liberal and democratic movement in Germany hit the German Revolution more seriously than anything else that happened to it during this period of setbacks. It would be pointless to argue about the morality and legality of English behavior from 1849 after a century. In any case, the two incidents illustrate how endangered the naval enterprise of the central government of the Reich was, also in terms of foreign policy and international law, as long as the German nation-state did not undoubtedly achieve recognition as a subject under international law and the federal central authority recognition of its power of representation under international law.

The Reich did not have an official national anthem. In addition to other patriotic songs, Was ist des Deutschen Vaterland by Ernst Moritz Arndt (1814), as it was sung at at least one of the homage celebrations , was widespread . Despite his 80 years of age, Arndt was a member of parliament in Frankfurt. The line as far as the German tongue sounds. was often quoted for determining the desired borders of the empire.

aftermath

The end of the National Assembly or the emerging empire is usually located in May 1849. But the actions of the National Assembly and the German central authority also had an impact later:

- The Frankfurt Imperial Constitution had a wide range of repercussions at the national and state level. This applies above all to the fundamental rights contained therein . The constitution of the German (Erfurt) Union was essentially a copy of the Frankfurt Imperial Constitution.

- The Reichsverweser transferred his powers to an Austrian-Prussian federal central commission on December 20, 1849 . The entire Bundestag, which had been dissolved in June / July 1848, only met again in the summer of 1851.

- The governorship for Schleswig-Holstein , set up by a Reich Commissioner , ended in early 1851 when federal commissioners replaced the governor government.

- Numerous MPs from the Frankfurt period belonged to the Erfurt Union Parliament and even to the Reichstag from 1867. One of the most prominent was Eduard Simson , President of the National Assembly and the constituent Reichstag .

- The Reichsflotte , founded by the National Assembly on June 14, 1848, was not dissolved or sold by the German Confederation until 1852/1853. Today's German Navy sees itself in the tradition of the Reichsflotte and therefore celebrates June 14th as its founding day.

- The Reich Election Act of April 1849 was the direct template for the Reichstag elections in 1867. The North German Federal Election Act of 1869 was based on it with only minor changes and remained in force until 1918.

- The General German Exchange Order of 1848 was permanently in force in almost all of Germany, even where it was not introduced by the legislation of the individual state. In 1869 the North German Confederation adopted it as a federal law. It was valid as a Reich law until 1933.

Evaluation and outlook

Although the central power and the imperial constitution had met with a great response from the German people, the actual activities of the National Assembly ended in May 1849. The imperial dignity was not accepted by any prince and the Reichstag was not elected. This was due to the Prussian coup, the illegal recall of members of the National Assembly by their individual states and the use of the military. In the subsequent historiography of the reaction era and thereafter, the revolution and the attempt to found a state were often ridiculed, demonized and interpreted as the failure of an incompetent, impractical professors' parliament.

For example, Herder's Conversations-Lexikon wrote from 1854 under the keyword "Germany":

“The year 1848 saw the general German revolution, the parliament in Frankfurt, the madness of democracy, the mad goings-on of the population in the first capitals, and finally the defeat of the revolution, after it had previously been disgraced and shamed. Shame covered. [...] No prudent man expects a unified German state in the future, that forbids counteraction from abroad, the antagonism between Catholics and Protestants, the power of Prussia, the still existing peculiarity of the southern and northern German tribes, but a stronger German alliance is quite conceivable, a federation that satisfies the national needs of life (national law, national economy, national politics) and puts an end to the ridicule of strangers about D. "

With a light hand, according to Günter Wollstein , the failure of the revolution was attributed to the “idealism” of the 1848s, while the power politics of the counter-revolution was glorified as a creative force. The failure was to a certain extent inevitable, because the many problems "an improvised new state building" hardly allowed. "Regardless of this knowledge, the unfinished and so difficult to complete German Reich of the year of the revolution emanated a fascination on which not only the greatest political hopes were placed at the time, but which also continued to have an effect in history for a long time."

Even before he had finally rejected the dignity of the emperor, the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV proposed a new attempt at unification to the German states. The Erfurt Union (1849/50) even had a parliament elected, but once again the indecision of the king and the resistance of the middle states prevented the unification of at least some German states. Wolfram Siemann : “Prussian politics fared little differently than the Frankfurt parliament before. That also refutes the still widespread judgment of the impractical actions of ideal dreamers in Frankfurt [...]. "

This is how Günter Wollstein thinks with regard to the foreign policy situation: Even if the king had accepted the Frankfurt Imperial Constitution in April 1849, the state attempt could also have ended in the surrender to Austria ( Olmütz punctuation in 1850), or in a war like 1866, but with a Prussian defeat, or even in a European war like in Napoleon's time "with devastating consequences".

Fifteen years passed between the restoration of the German Confederation in 1851 and Austria's defeat in the German War in 1866. During this time Prussia had risen economically, had upgraded itself militarily and enjoyed Russia's benevolence . In general, Germany grew closer and closer together as a result of the growing industrial revolution with its general progress (railways, telegraphy). Under these conditions, the Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck succeeded in 1867 in founding the North German Confederation with the North German small states . It was not until the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/1871 that the southern German kingdoms and grand duchies joined the federation, which was subsequently renamed the German Empire .

See also

literature

- Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, ISBN 3-17-009741-5 .

- Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Diss., Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main [a. a.] 1997, ISBN 3-631-31389-6 .

supporting documents

- ↑ With regard to the imperial constitution, see: Simon Kempny: State financing after the Paulskirche constitution. Investigation of the financial and tax constitutional law of the constitution of the German Empire of March 28, 1849 (Diss. Münster), Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2011, p. 23.

- ^ Stefan Danz: Law and Revolution. The continuity of the state and legal system as a legal problem, illustrated using the example of the November Revolution of 1918 in Germany. Publishing house Dr. Kovač, Hamburg 2008, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Stefan Danz: Law and Revolution. The continuity of the state and legal system as a legal problem, illustrated using the example of the November Revolution of 1918 in Germany. Publishing house Dr. Kovač, Hamburg 2008, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Stefan Danz: Law and Revolution. The continuity of the state and legal system as a legal problem, illustrated using the example of the November Revolution of 1918 in Germany. Publishing house Dr. Kovač, Hamburg 2008, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1997, p. 370 (Diss. Frankfurt am Main).

- ↑ a b Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, p. 624.

- ^ A b Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 626.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1997, p. 371/372.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, p. 634.

- ↑ Ulrich Huber: The Reich law on the introduction of a general exchange order for Germany from November 26, 1848. In: JuristenZeitung. 33rd Volume, No. 23/24 (December 8, 1978), pp. 788/789.

- ↑ Ulrich Huber: The Reich law on the introduction of a general exchange order for Germany from November 26, 1848. In: JuristenZeitung. 33rd Volume, No. 23/24, December 8, 1978, p. 790.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, p. 635.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, p. 635.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848) , Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main [u. a.] 1997, pp. 143/144.

- ↑ Konrad Canis: Bismarck's Foreign Policy 1870 to 1890. Rise and Endangerment. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn [a. a.] 2004, p. 20.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1997, p. 381.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 638.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1997, p. 381.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848) , Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main [u. a.] 1997, p. 371/372.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848) , Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main [u. a.] 1997, pp. 376, 379.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848) , Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main [u. a.] 1997, pp. 387/388.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 626/627.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848) , Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main [u. a.] 1997, p. 379.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 627.

- ^ Ralf Heikaus: The first months of the provisional central authority for Germany (July to December 1848) , Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main [u. a.] 1997, p. 375.

- ↑ Ulrich Huber: The Reich law on the introduction of a general exchange order for Germany from November 26, 1848. In: JuristenZeitung. 33rd Volume, No. 23/24 (December 8, 1978), p. 788.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 648.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 648/655.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 649/650.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 655.

- ↑ Wolfram Siemann: The political system of reaction. In: ders .: 1848/49 in Germany and Europe. Event - Coping - Memory . Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn [a. a.] 2006, p. 220.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 650.

- ^ Günter Wollstein: The 'Greater Germany' of the Paulskirche. National goals in the bourgeois revolution of 1848/1849. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 186/187.

- ^ Günter Wollstein: The 'Greater Germany' of the Paulskirche. National goals in the bourgeois revolution of 1848/1849. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 169.

- ↑ see Imperial Constitution § 1

- ^ Günter Wollstein: The 'Greater Germany' of the Paulskirche. National goals in the bourgeois revolution of 1848/1849. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 23/24.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: Documents on German constitutional history. Volume 1: German constitutional documents 1803-1850. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1978 (1961). No. 108a (No. 103). Reich Law on the Elections of Members of the People's House of April 12, 1849. p. 399, fn. 8.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: Documents on German constitutional history. Volume 1: German constitutional documents 1803-1850. 3rd edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1978, p. 401, no. 109: “Reich Law Regarding the Introduction of a German War and Trade Flag” of November 12, 1848 (Reichsgesetzblatt 1848, p. 15 f.).

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 659.

- ^ Walther Hubatsch: The German Reichsflotte 1848 and the German Confederation. In: ders. (Ed.): The first German fleet 1848–1853. ES Mittler und Sohn, Herford / Bonn 1981, pp. 33/34.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 650.

- ^ Jonathan Sperber : Festivals of National Unity in the German Revolution of 1848–1849. In: Past and Present. 136, pp. 114-138, printed in: Peter H. Wilson (Ed.): 1848. The year of revolutions. Pp. 302/303.

- ^ Karl Griewank: Causes and consequences of the failure of the German revolution of 1848. In: Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde, Rainer Wahl (ed.): Modern German Constitutional History (1815-1914). 2nd edition, Verlagsgruppe Athenäum, Hain, Scriptor, Hainstein, Königstein / Ts. 1981, pp. 40/41.

- ↑ Germany. In: Herders Conversations-Lexikon. Volume 2, Freiburg im Breisgau 1854, pp. 355-364. See Zeno.org , accessed July 7, 2014.

- ^ Günter Wollstein: German History 1848/49: Failed Revolution in Central Europe. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [a. a.] 1986, p. 176/177.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: 1848/49 in Germany and Europe. Event, coping, memory. Schöningh, Paderborn [a. a.] 2006, p. 208.

- ^ Günter Wollstein: German History 1848/49. Failed revolution in Central Europe . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1986, p. 164/165.