Reform of the German Confederation

A reform of the German Confederation (or federal reform ) was discussed at different times in the German Confederation from 1815 to 1866. This was particularly the case in the periods when Austro-Prussian cooperation was disrupted, namely from 1848 to 1850 and from 1859. The great powers Austria and Prussia tried to strengthen their own position of power through reform. The medium-sized states such as Bavaria or Hanover, however, did not want to give Austria or Prussia an even greater supremacy.

An important point was the expansion of the federal purpose , so that the defense alliance would have become an instrument for standardizing law and economic and social policy. The contemporary catchphrase was "Welfare of the German People". Proponents of reform wanted to give the federal government new organs instead of or alongside the Bundestag , such as a parliament and a federal court. In addition, there was criticism of the Federal War Constitution , which was unable to guarantee a powerful armed forces . For some, the goal was to turn the confederation into a nation- state .

In the 51 years that the federal government existed, no major federal reform has come about. Austria and partly the medium-sized states wanted to preserve the old state, several medium-sized states expand the federal government, while at times Prussia and the small states sought a German federal state. The differences and the Austro-Prussian rivalry ultimately led to the German War and the dissolution of the Confederation in 1866.

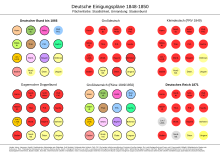

Overview

| Federal territory | head | organs | Federal purpose | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starting position | originated through orientation on the borders of the Old Reich ( Greater German solution ); Admission of the Prussian eastern provinces 1848–1851 | without; Austrian envoy presiding over the Bundestag | Bundestag as the representation of the member states | Defense of the federal territory against internal and external attacks |

| Seventeen draft of the Bundestag 1848 | previous federal territory; Prussian eastern provinces and Schleswig | hereditary emperor | Imperial power; Reichstag with lower house and upper house | universal |

| Central Power Act in the German Empire 1848/1849 | previous (greater German) federal territory;

Schleswig deputies |

Imperial Administrator , elected by the Imperial Assembly |

Provisional central authority (Reich administrator and minister);

Reich Assembly as representative of the people; Plenipotentiary of the state governments (without rights) |

universal |

| Paulskirche constitution 1849 | de facto small German federal territory with clauses for a possible inclusion of Schleswig and Austria | hereditary emperor with suspensive veto against laws; Election of the King of Prussia as emperor | Imperial power (emperors and ministers), Reichstag with the People's House and House of States | universal |

| Erfurt Union 1849/1850 | Prussia and other states (especially in northern and central Germany) that have joined the union | King of Prussia as hereditary union leader; Legislative rights with veto together with the Princely College | Union power (union board and ministers), princes' college, German parliament with people's house and house of states | universal |

| Greater Austria Plan 1849 | Federal territory after inclusion of all areas of Austria | without | additional customs and trade policy | |

| Four Kings Alliance 1850 | Federal territory after inclusion of all areas of Austria | without | Federal government with members from the states; National representation with representatives of the state parliaments; Federal court | in addition, customs and trade policy, standardization of law and dimensions, infrastructure and transport |

| Frankfurt Reform Act 1863 | Federal territory | without | Federal Directorate with members from the states; Federal Council as state representative for most important decisions; Assembly of representatives with representatives of the state parliaments; Princely Assembly; Federal court | additionally welfare of the people and standardization of the law |

| Prussian reform plan 1866 | Small Germany (excluding Austria and Dutch territories) | unspecified "federal authority" | State representation, elected national parliament | universal |

| North German Confederation 1867 | Northern and Central Germany and Schleswig | King of Prussia as holder of the Federal Presidium | Federal authority (Federal Presidium with Federal Chancellor ), Federal Council , Reichstag | universal |

| German Empire 1871 | Small Germany and Alsace-Lorraine | King of Prussia as holder of the Federal Presidium with the title of German Emperor | Imperial power ( Emperor with Imperial Chancellor ), Bundesrat, Reichstag | universal |

Structure of the German Confederation

The German Confederation was a confederation of states with federal features. The states retained their sovereignty, but the federal government was able to adopt federal resolutions. These federal resolutions and federal laws were binding on the states. The federal government could have moved in the direction of the state through more pronounced federal legislation. Whether the federal state could ultimately have been implemented without breaking the law of the German Confederation is a matter of dispute in the specialist literature. In any case, unanimity was required for the major decisions in the Bundestag, which made reform considerably more difficult.

On top of that, the federal government had only a limited federal purpose , in contrast to a federal state with its universal competence. Essentially, the federal government was intended for internal and external security: to fight insurrections and to defend the federal territory against attacks from outside or between member states. General welfare, i.e. the cultural, economic and social areas, was not a federal purpose. That is why the expansion of the federal purpose has repeatedly been a point of contention in the context of federal reform.

Jürgen Müller calls the federal act “a rather dry organizational statute in terms of both character and intention”. Further development was expected in the coming years. This was discussed primarily from 1817 to 1819. General federal laws were intended to promote economic and legal integration. A federal executive still to be established would implement the federal laws, a future federal court would ensure legal unity and legal certainty, and a popular representative body would involve the nation in federal laws.

Starting position of Austria

Austria was one of five major European powers. Overall, it was considered to be much more important than Prussia. Austria was primarily concerned with maintaining the status quo and its supremacy. In the German Confederation she expressed herself by the fact that the Austrian envoy presided over the Bundestag. His “presidential vote” was decisive in the event of a tie in the Select Council. Apart from that, the “presidential envoy” of the “ presidential power ” Austria had no privileges.

Austria used the German Confederation as an instrument to fight against national, liberal and democratic tendencies. This was not only due to the emperor's conservative attitude. In addition to the favored Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Italians and other nationalities lived in the multinational structure of Austria. From an Austrian point of view, a democratic development ran the risk of giving new impetus to nationality issues. Austria strictly rejected a German federal state because its non-German areas could not have belonged to it (the other German states would not have accepted this because they wanted as few nationality conflicts as possible in the federal state). The solution would have been that the Austrian Kaiser would only have ruled in personal union for the non-German areas . Austria was afraid that it would no longer be able to successfully force the non-German areas under its rule.

Austria was hardly interested in reforming the German Confederation. At best, it strove to join its entire territory to the federal territory. As a result, it would have enjoyed federal protection for all of Austria in a military emergency. In addition, the “self-proclaimed European regulatory authority” (Jürgen Müller) could have used the federal anti-liberal measures for its entire territory. For this goal Austria would have been prepared to make concessions on other points, for example to expand the federal purpose. The red line was the establishment of a directly elected German national parliament, because that would have led the political dynamic into the federal state.

Starting position of Prussia

The Prussian kings shared the conservative attitude of the Austrian emperors. Therefore, they supported Austria's anti-liberal policy in the federal government for the longest time: essentially from 1815 to 1848 and in the reaction period from 1851 to 1858 and again briefly from 1863 to 1865 in connection with the German-Danish War . During these periods there was a dualistic (Austro-Prussian) leadership in the federal government. The leading power Austria discussed closely with Prussia and only presented proposals to the Bundestag after an agreement with Prussia had been reached.

Prussia, however, struggled with being only the second most important power in the German Confederation after Austria. From the Prussian point of view, Austria's supremacy seemed to be less and less justified over the years. It is said that Prussia grew into Germany in the 19th century, while the opposite was true for Austria. In the course of time, more inhabitants lived in the Prussian federal territory than in the Austrian federal territory.

That is why Prussia always sought ways to improve its position in the discussions on federal reform. So there were proposals to make the Prussian king permanently a federal commander instead of only appointing one in the event of war. Austria refused this because it would have "mediatized" its troops (subordinate to another ruler). Above all, however, Prussia demanded the "alternate": The chairmanship in the Bundestag should alternate between the Austrian and the Prussian ambassador. Austria did not want to make such a symbolic concession.

Prussia was more open than Austria to the idea of converting Germany into a federal state. The Polish minority in East Prussia was numerically far less significant than the Hungarians in Austria. Especially with a small German solution, i.e. a federal state without Austria, Prussia fell to the leading role.

When this became a conceivable option after 1848, the Prussian king was also faced with the question of whether the state constitution might restrict his own position in the state too much. For the king, granting more “freedom” or more “rights” to the subjects was only attractive if he could rule over a larger area (more “unity”) and thereby gain more weight in foreign policy (more “power”).

Finally, there was another interesting option for Prussia: hegemony in northern Germany . In both 1849 and 1866, Prussia initially sought a small German federal state. With the Erfurt Union (to some extent) and then with the North German Confederation , Prussia was able to realize at least one North German federal state.

During the time of the German Confederation, Prussia offered Austria such a division of Germany into north and south. The instrument for this was to be the appointment of two permanent commanders-in-chief for a divided federal army : the Prussian king in the north and the Austrian emperor in the south. However, the situation was fundamentally different. Prussia was able to force the comparatively small states in northern Germany into its sphere of influence. Austria, on the other hand, would have faced relatively strong states in southern Germany , especially Bavaria. If Austria had attempted to partition, it would have come out empty-handed, according to the astute analysis of the Prussian statesman Wilhelm von Humboldt as early as 1816.

Starting position of the medium-sized states

After Austria and Prussia, there were several individual states in the Federation, which by their size stood out from the number of the other states. This group of “medium-sized states” is not clearly defined. In any case, this includes the other kingdoms of Bavaria, Hanover, Saxony and Württemberg. Mostly the Grand Duchy of Baden is one of them, sometimes also Hessen-Darmstadt and Hessen-Kassel . The term “ Third Germany ” is known for the medium-sized states and partly also for the small states .

The middle states were primarily concerned with maintaining the status quo and their independent position. They did not want to be dominated by either Austria or Prussia. The delicate balance between the two great powers was in their interests; most medium-sized states rejected solutions that would have pushed one of the two great powers out of the federal government.

Baden repeatedly showed interest in joining a small German federal state under Prussian leadership. Most of the middle states rejected the transition to the state. Nevertheless, they wanted the German Confederation to be expanded, with new organs and, above all, with uniform rules in the field of law and economics. The four-king alliance of 1850 corresponds to this direction, as does the Frankfurt Reform Act of 1863, with which Austria wanted to accommodate the medium-sized states.

Cooperation between the middle states often failed because the middle states had different interests. Bavaria was by far the largest medium-sized state; the rest feared being dominated by Bavaria. That is why they had little interest in forming a Third Germany. They also rejected a "trialist" solution, in which Germany would have consisted of Austria, a Prussian-dominated northern Germany and a southern German bloc. The latter could have emerged from the Prussian federal reform plan of 1866, which provided for Prussian leadership in northern Germany and Bavarian leadership in southern Germany. But Bavaria did not dare to go into this plan without the consent of the other states (including Austria). Even after the war of 1866, Bavaria did not form a South German Confederation , which the Peace of Prague had spoken of.

Starting position of the small states and foreign rulers

Furthermore, there were over twenty other smaller states in Germany. The number fluctuated over time. Most were in the middle and north of Germany and were heavily influenced by Prussia. At most, Liechtenstein was permanently a partisan of its large neighboring country Austria. Because of their small size, they could hardly pursue an independent policy and were completely at the mercy of the larger powers in the event of war.

Most of the small states wanted the German Confederation to be strengthened, which protected them militarily. They were also positive about an expansion of the federal purpose, even a transition to the state. However, they remained concerned about their state existence as such; they did not want to become part of a unified German state . That played a role in the mediatization question of 1848/1849 . Most of these states, however, welcomed the federal constitution of 1849.

A number of states were members of the German Confederation, but their sovereign was the ruler of a foreign empire. One of these connections lasted until 1837 when the personal union between Hanover and Great Britain ended. Furthermore, the Danish king was sovereign of the federal member Holstein and the Dutch king was sovereign of the federal member Luxembourg (from 1839 also of the Duchy of Limburg ).

Denmark and the Netherlands had no interest in federal reform. For them, the federal government was a purely military alliance, whose protection was welcome in the event of a defense or uprising. In particular, they rejected the creation of a German nation-state. Only in 1830, during the Belgian uprising , did the Dutch king consider joining the whole of the Netherlands to the Confederation for security reasons. However, this would have been extremely unpopular in the northern Netherlands as well as in Belgium.

Restoration and March 1815–1848

First years of the German Confederation

In the first years after 1815 and in March there were hardly any demands for a federal executive, but there were demands for a federal court and a representative body. For the federal court one could refer to the tradition of the imperial courts before 1806. The middle states, however, conscious of their recently won sovereignty, had prevented a supreme court to which they should have subjected their own judiciary. Despite advances at the Vienna Conferences in 1819 and the Vienna Ministerial Conference of 1834 , only an emergency solution was found: According to the Austrägalordnung of 1817, it was possible to convene a special court for specific disputes.

Representation of the people was only called for in the Vormärz through petitions and parliamentary inquiries in state parliaments, for example by Carl Theodor Welcker in the Baden Chamber in 1831. Welcker wanted to see a national parliament set up next to the Bundestag to prevent the liberal Baden press law from being cashed in. The state government was indignant about this treatment of supposed foreign policy in the chamber, and the chamber shied away from a conflict.

In spite of the other intentions of some of the founding members, there were no discussions about a major reform or expansion of the federal government in the first three decades. At least not on the part of governments or at the federal level. Instead, the federal government developed into an instrument to suppress the liberal and national opposition in Germany. The liberals were accused of wanting to destroy the federal government in favor of a federal state.

Criticism of the Federal War Constitution 1830/1832 and 1840/1841

Until 1830 the security system of the German Confederation was not challenged by external crises. However, around 1830/1831 and 1840/1842 this changed drastically, and in Frankfurt there was a very serious discussion about the possibility of France attacking Germany. In the first case it was about the European crisis following the French July Revolution and the Belgian uprising , in the second case about the Rhine crisis and its consequences.

On the one hand, the Federal War Constitution provided for a federal army with contingents from the individual states and minimum standards. On the other hand, the sovereign princes retained the ultimate decision over their troops. In an emergency, the mobilization took more than the originally estimated four weeks. Austria and Prussia did not succeed in reaching an understanding on reform. The appointment of a federal general remained controversial.

Radowitz Plan 1847

General Joseph von Radowitz was Plenipotentiary for Prussia at the Bundestag; as early as the mid-1840s he was of the opinion that Prussia should give up its blockade and tackle federal reform. It was particularly well received by the Baden government because it was under pressure from the liberal opposition. The government should regain its reputation by promoting joint federal activities. On November 27, 1847, the Baden parliamentary envoy Friedrich von Blittersdorf wrote to his Austrian colleague that Austria should take the national movement into consideration and, with the help of the federal government, "unfold the German banner [...]".

In September 1847 Radowitz won the Prussian king over to the idea of national unification through an agreement between the governments (and not through the election of a national parliament). On November 20, 1847, Radowitz presented a "memorandum on the measures to be taken by the German Confederation".

Prussia was to provide the impetus for the creation of a central authority with the aim of: “Strengthening the ability to defend itself; arrange and supplement legal protection; meet the material needs. ”The states that determined the 17 votes in the Senate Council of the Bundestag should send ministers to a congress. This would determine the "highest standards" for the reform of the nation state. Alternatively, special associations would have to be founded, comparable to the Zollverein, in order to tackle individual tasks. However, these special associations should eventually merge under the umbrella of the federal government.

Radowitz was immediately sent to Vienna (November – December 1847) to discuss the plan with Austria. However, the question of intervention in Switzerland put the federal reform in the background. In February 1848 Radowitz made sure in Berlin that the king obliged his government to act on the plan (February 21). Radowitz then went back to Vienna, where he and Metternich signed a punctuation on March 10, 1848. She invited all German governments to a conference in Dresden on March 25th. This Austro-Prussian conference plan became the counter-model for an agreement from below through a parliament. The uprisings in Berlin and Vienna soon made this path impossible.

Revolutionary period 1848-1851

From March 1848 the German question began to move again. Under pressure from the revolution at the time, the German princes appointed liberal ministers and showed their willingness to found a German nation-state with a head of the Reich. Contemporaries firmly assumed that Germany would soon be unified by a liberal constitution. Already in the summer and especially in the autumn of 1848 a reaction set in: the princes regained the upper hand and dared to confront revolutions and reforms more aggressively.

After the actual revolution was suppressed in the spring of 1849, however, attempts to reform Germany did not cease. Both Austria and Prussia made offers to the other states. Since neither side could prevail, the old German Confederation was finally fully restored in the summer of 1851, without any significant reforms.

Private initiatives

The committee of seven was elected by the Heidelberg assembly . He ensured that a pre-parliament convened in Frankfurt, which stood next to the Bundestag and also prepared the later election of the Frankfurt National Assembly. The Heidelberg Assembly, the Committee of Seven and the Pre-Parliament did not have any real democratic legitimacy; the pre-parliament consisted of members of the state parliaments, but it was appointed and represented the German states very unevenly.

The liberal majority of the Committee of Seven agreed on a program for federal reform on March 12, 1848: the federal government was to be given far-reaching responsibilities (including foreign policy, trade policy and legal standardization), and the federal organs were to be expanded. There should be a federal head appointed ministers. The Bundestag should become a Senate of the individual states, next to it a directly elected People's House would appear. This program was presented to the pre-parliament. However, it had no legitimacy to commit the National Assembly to such a program.

In the pre-parliament, Gustav Struve submitted a motion on behalf of the radical left that Germany should immediately become a democratic republic, modeled on the USA . In addition, the pre-parliament should stay together permanently and serve as a legislative body. An executive committee of the pre-parliament would have had executive power. However, there was no majority in the pre-parliament for this proposal.

Reform proposals by the Bundestag in March / April 1848

The states of the German Confederation appointed liberal or reform-minded delegates to the Bundestag. This Bundestag tried to calm the people down through reform measures and to prepare the German "federal state", which was soon to be expected. Among other things, a Bundestag committee developed the Seventeen draft with the main features of a future Reich constitution. This draft of a "Reich Basic Law" was already quite similar to the later Frankfurt Reich Constitution.

In addition, on May 3, 1848, the Bundestag decided to set up a federal directorate, a government that should consist of representatives from several states. One thought of three representatives of the largest states. Because there was disagreement about this, and because the election of a National Assembly had already been initiated, such questions were left to the National Assembly.

German Empire 1848/49

With two resolutions , the Bundestag determined that the individual states should elect the representatives to a national assembly. The National Assembly had the task of drafting a constitution and agreeing it with the individual states .

The National Assembly in Frankfurt began its work on May 18, 1848. Contrary to the original mandate, it saw itself as the central organ for the whole of Germany:

- With the Central Power Act, it set up a provisional constitutional order which was initially called the “German Federal State” and soon “German Reich”.

- They chose a Reichsverweser as a substitute monarch, who appointed Reich Ministers and together with them formed the Provisional Central Authority .

- The National Assembly saw itself as the Parliament of the Reich and passed Reich laws .

The German states agreed to this and recognized the election of the imperial administrator. In addition , the Bundestag ended its activities in favor of the Reich Administrator on July 12th . In this way, the Bundestag tried to establish continuity between the German Confederation and the German Reich. At that time, the National Assembly still interpreted itself as a revolutionary organ, but over time it understood how useful it was to gain legitimacy through the German Confederation. The German Confederation was undisputedly a universally recognized entity, both at home and abroad.

The German Reich was recognized by some foreign states. However, the central authority did not always succeed in enforcing its orders domestically. As early as the decree of homage in the summer of 1848 it became apparent that the larger states in particular only obeyed centralized power if they themselves considered it useful.

In the spring of 1849 the Frankfurt constitution was ready. The National Assembly felt it was entitled to let it come into force alone. 28 states recognized the constitution, but not the larger ones. Above all, Prussia fought the National Assembly and renewed uprisings with violence. That was the end of the actual revolution, but not the attempt at unification.

Austria and Prussia subsequently submitted their own proposals to reform the German Confederation or to unite Germany as a federal state. They were concerned with increasing their own power. It was important whether they could win public opinion and, above all, the support of medium-sized states like Bavaria.

Erfurt Union 1849/50

The Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV wanted to found a German Empire himself. This attempted agreement was later given the name Erfurt Union because the associated parliament met in the city of Erfurt . Joseph von Radowitz was the pioneer and driving force . The timetable was as follows:

- On May 28, 1849, Prussia agreed the Three Kings Alliance with Hanover and Saxony , which provided for the establishment of a federal state.

- Two days later there was a draft constitution, the Erfurt Union Constitution . The model was the Frankfurt constitution. But it had been rewritten in a conservative and federalist way to please the princes of the middle states.

- In June right-wing liberal ex-members of the National Assembly ( Gotha post-parliament ) met and supported, albeit with reservations, the Prussian union policy.

- The Union parliament was elected in the winter of 1849/1850 . The only task was to adopt the draft constitution. The right-wing liberal majority in parliament did this in April 1850 and submitted liberal proposals for amendment to the member state governments.

This would actually have established the union, and the Prussian king as the union executive would now have had to set up a union government. The king had meanwhile lost interest in the Union because the constitution was still too liberal for him and the most important German states stayed away permanently. For so little unity he did not want to allow so much freedom. So he first asked the other princes to confirm the constitution. The project came to nothing even before Austria put an end to it at the end of 1850.

Greater Austria Plan

The Emperor of Austria imposed a new, centralized constitution on his empire in March 1849 . Austria thus signaled that it was not available for a large German nation-state. According to the Frankfurt National Assembly, the emperor could only have remained ruler of his different countries in personal union. They should have had a separate government and administration. The Austrian emperor feared, however, that as a mere joint head of state he would not be able to keep his previous countries together.

However, Austria had to make its own, alternative offer for the future to the German public in order not to be perceived as a purely negative force. The plan of a Greater Austria served this purpose . It was also named Schwarzenberg - or Schwarzenberg-Bruck-Plan , after its inventors .

“Greater Austria” would have meant that all parts of Austria would have been included in the German Confederation. For Austria this had the advantage that in future Germany would have been obliged to help in wars and uprisings throughout Austria. For the other German states, this prospect was not very attractive. In addition, such a large Austrian structure could not have been a nation-state because of the many nationalities in the whole of Austria.

In order to make Greater Austria more palatable to the other German states, Austria wanted to allow at least a limited federal reform. So it could imagine a kind of federal government and partly also an organ of representatives or MPs of the individual states. However, it should not be an elected parliament, because that could have called for a nation-state in the future. The German Confederation should also become attractive through a customs union and a certain standardization of law and trade policy. But Austria also saw narrow limits there - in any case, the federal government was not allowed to guarantee any fundamental rights.

Four Kings Covenant February 1850

In February 1850, the Erfurt Union Parliament was about to meet. For the four kingdoms of Bavaria, Württemberg, Saxony and Hanover, this was the reason to make a concrete, positive counter-offer to the Union to the public and the other states. Austria supported her proposal in the background.

According to the four-king alliance, the federal government should have a federal government and a federal court. Austria, Prussia and the other states were each to send a hundred members to a national representation as representatives of the respective parliaments of the individual states. The states should work more closely together in the field of trade and law, but the provisions on this were formulated very cautiously.

Austria was initially positive about the proposal, but made reservations. The kingdoms understood that Austria was only concerned with a tactic to oppose the Erfurt Union. Austria also hoped to gain sympathy for Greater Austria in this way. In the long run, Austria had no real interest in strengthening the federal government.

In the summer of 1850 Schwarzenberg made a six-point proposal to the Prussian ambassador, Count Bernstorff:

- A large German federation with all of Austria, with a customs union, without popular representation, but with strong central authority that Austria and Prussia exercise together. In central power and in the Bundestag, both should have equal rights.

- A closer federation of states that wanted to belong to it, with Prussia at the head, but without a German Empire emerging from it

On July 8, 1850, however, Austria added a few conditions that invalidated the generous proposal for Prussia: In the narrower confederation, there should be no parliament, but at most one joint representation of members of the state parliament. Prussia should describe the Erfurt constitution as impracticable.

Autumn crisis and Dresden conferences 1850/51

In the autumn crisis of 1850 , war almost broke out between the states of the Union and the states of the Rump Bundestag. In the end, however, Prussia had to give up the Union - also due to Russian pressure. In the negotiations with Austria that led to the Olomouc punctuation , Prussia achieved at least one apparent gain: A German conference was negotiated at which a federal reform was to be discussed.

At the Dresden Conferences from December 1850 to May 1851, Austria and Prussia came very close to an agreement. All areas of Austria and Prussia should belong to the federal government and the federal government should have a federal executive. This federal government would have had much more to determine than the old Bundestag, although, similar to the Senate Council, all states would still have belonged to it, with voting advantages for the larger states. A parliament and a federal court were also on the agenda, together with an expansion of the federal purpose to include trade, customs, transport and the standardization of weights and measures.

The agreement failed for two reasons. The small states were afraid that the two great powers would come to an agreement over their heads; they would have accepted a “mediatization” in the federal state (the Erfurt Union), but not in the confederation. In addition, Prussia had concerns about whether Austria would not become too powerful in an enlarged German Confederation. So it again demanded that the chairmanship of the Federation between Austria and Prussia should alternate (the alternate). It wanted a strong federal executive, but no further expansion through popular representation and courts. As long as Prussia understood the federation as an instrument of power for Austria, it refused to strengthen the federation and interfere in the internal affairs of Prussia.

The middle states tried unsuccessfully to implement at least some reforms. When the Bundestag met again after the conference on July 8, 1851, only one result was achieved as a federal resolution: a certain military contingent had to be made available quickly to enforce the federal resolutions.

Response time 1851-1859

From 1851 to 1859 Austria and Prussia worked closely together again, as they did before the revolution. According to Jürgen Müller, they could not agree on a federal reform in the sense of all-German interests, but only on the suppression of the revolution, liberalism and the national movement. However, their response measures were less successful than desired because of the opposition of the middle states, and their instruments remained relatively blunt. The middle states warned against repeating the merely repressive federal policy. They wanted a gradual, defensive modernization.

Initiatives at the Bundestag and in the medium-sized states

In July 1851 the Bundestag elected committees for a federal court and a common commercial policy. Regarding the Federal Supreme Court, however, the disagreement between the states seemed to have grown even greater than in Dresden. It was similar with trade policy. The standstill was not so much due to the Bundestag envoy in Frankfurt, not even to the conservatives. It was the governments, especially those of Austria and Prussia, who had no interest in reforms. When asked whether Austria wanted a federal court at all, the presidential envoy did not even receive an answer from his government. In trade policy, it was above all Prussia that preferred to regulate trade policy and customs outside of federal policy. Its customs union policy showed the weakness of the federal government, which was also entirely in the interests of Prussia as long as it was not on an equal footing with Austria. As a great power, it did not want to submit to majority decisions.

The Saxon head of government Friedrich von Beust tried to persuade the medium-sized states at least to adopt a joint approach in customs policy: Austria should not be excluded again when the customs union was renewed. In April 1852 the representatives of Bavaria, Saxony, Baden, Hessen-Darmstadt, Kurhessen and Nassau actually met in Darmstadt. Beust endeavored to hold regular conferences of the medium-sized states, beginning in 1853 in Frankfurt, the city of the Bundestag. This would have given the meetings the character of a political demonstration. Such a policy of the medium-sized states, however, failed most of all, because of Bavaria. Bavaria also recognized the merging of the great powers as a danger, although it thought less of the fate of the federal government than of its own independence.

Isolated initiatives, such as the reform plan of the Coburg prince , found insufficient support and did not solve the basic problem: The Bundestag, as the representative of the member states, could not be transformed into a government capable of acting.

Sardinian War 1859

Partial questions of a federal reform led again and again to conflicts between the two great powers during the reaction time. One of them was the one about the Federal General : In the run-up to the Crimean War (1853-1856) and the Sardinian or Italian War (1859), the beleaguered Austria demanded the mobilization of the Federal Army and the appointment of a Commander in Chief, a Federal General according to the Federal War Constitution. Prussia only wanted to appoint a federal general if it could achieve its own goals. First Prussia demanded someone from its own country who should not have to submit to the instructions of the Bundestag, then a division of the federal army. Prussia was to lead the North German contingents, Austria the South German contingents. There was no longer any border crossing and appointment of the federal general: Austria suddenly concluded the preliminary peace of Villafranca (July 1859) and renounced Lombardy.

The Sardinian War was of the utmost importance for federal politics because the federal member Austria was at war with Sardinia-Piedmont and France. Even if the fighting did not take place in the federal territory, but in the Austrian-ruled northern Italy, the question of the endangerment of the federal territory arose. It was feared that it would extend to include the Rhine, among other things. In public opinion, Prussia's hesitation was seen as a betrayal of the German cause out of calculation and self-interest.

During this time Prussia lost political prestige, Austria military. In Vienna there was a certain willingness to undertake domestic political reforms. In addition, the deficiencies of the Federal War Constitution had become abundantly apparent. The public in Germany passionately discussed the national question. The Sardinian War therefore brought movement into the federal reform debate.

Renewed reform debates 1859–1866

Non-State Actors

After Prussia pursued a more liberal domestic policy, the resurrection of political associations was also possible. The German National Association of 1859 called for a small German federal state under Prussian leadership and thus stood in the tradition of the right and left (liberal) center in the Frankfurt National Assembly. The association explicitly referred to the Frankfurt Imperial Constitution and the Frankfurt Election Law from 1849.

In 1862 the German Reform Association was formed as a Greater German counterpart. He was less anchored in the north than in the middle states and wanted a Germany with Austria, as it began to liberalize after the Italian War. His way to achieve this was a federal reform with an advisory parliamentary assembly appointed by the state parliaments. For a time, the former Prime Minister Heinrich von Gagern was one of his board members.

In addition to the two mentioned associations, the historian Andreas Biefang also counts the Trade Day, the Economists' Congress and the Congress of Representatives among the national organizations of the time. They were no longer federal, but centralized and had many double memberships. Biefang identified a functional elite of about eighty, mainly Protestant and academic, who developed strategies and implemented them in political action. She wanted to establish a federal state on the model of 1849 and subordinated all other questions to this goal.

This movement started out from a liberal Prussia and was disappointed when Bismarck's prime ministerial presidency (from 1862) was not a short transition period. In the course of the 1860s she saw how Germany was increasingly shaped by Greater Prussian annexationism and anti-Prussian particularism. The liberal national movement was forced to compromise with Bismarck if it wanted to achieve anything at all.

Germany and Austria had drifted apart, culturally and economically, as early as the early 1860s. Hardly any Austrians took part in the national civil organizations in Germany. Not even with the Greater German-oriented Reformverein this was different. A study of the former members of the Frankfurt National Assembly and their networks showed something similar. Among the German-Austrians themselves, only the smallest of three major political groups was interested in German affairs, namely the autonomists, who wanted the Hungarians to be more independent. The other two were marked by a strong Austrian imperial patriotism. Socially, according to Andreas Biefang, the constitutional separation of 1866 was already prepared.

Reform debates 1860–1863

After the lost war against Piedmont-Sardinia and France in 1859, Austria tried to restore internal order. It also passed a constitution over ten years after Prussia. Only then was it legitimized to address the German question to the public, whose approval was necessary for a federal reform policy even then. The Prussian government, on the other hand, was involved in a constitutional conflict with the liberal state parliament .

In the Austrian government, the group around State Chancellor Rechberg wanted to revive the alliance with Prussia, but without sharing the chairmanship of the Bund with Prussia. But the group around the former Frankfurt Reich Minister Anton von Schmerling prevailed: They wanted to reform the federal government together with the medium-sized states and saw cooperation with Prussia as a tactical means at most.

The medium-sized states in turn endeavored on the initiative of Bavaria and Saxony to develop a common policy towards the great powers. Starting points were a standardization of the law, the measures as well as the trade policy and above all a reform of the Federal War Constitution. These initiatives of the Würzburg Conferences remained weak, however, because the medium-sized states did not always agree among themselves.

Prussia came closer to the national association in a certain way and in December 1861 demanded a small German federal state with the Bernstorff Union Plan, excluding Austria. That drove most of the medium-sized states into the arms of Austria. The imperial state saw the possibility of winning over the medium-sized states with a large-scale reform initiative, isolating Prussia and ending the federal reform debate for a long time. With this, Austria would have prevented a federal state initially.

At the Frankfurt Fürstentag in September 1863, the representatives of the German states present discussed Austria's reform plan: the Frankfurt Reform Act . Its adoption would have given the German Confederation new organs instead of the Bundestag and expanded the federal purpose. In this way Austria met the wishes of the medium-sized states. Prussia, however, had stayed away from the Fürstentag and demanded a directly elected national parliament and equal rights with Austria. The middle states feared the isolation of Prussia and with it the supremacy of Austria, so that they let the project fail.

Final phase 1864–1866

Soon afterwards Austria and Prussia started working together again. In the German-Danish War of 1864 they prevented the creation of an independent, liberal Duchy of Holstein or Schleswig-Holstein. But they quarreled over the division of their booty: Prussia wanted to annex Holstein and Schleswig. Despite Prussian proposals for the future of these two duchies and the cooperation in the Federation, such as the Gablenz Mission , the conflict between Austria and Prussia continued to come to a head.

Prussia did not succeed in winning Bavaria over to a small German federal state in which Prussia would have dominated the north and Bavaria the south. Nevertheless, on June 10, 1866 , Prussia came up with a federal reform plan. Prussia no longer used the Bundestag for this purpose, but sent the plan directly to the states. The main demand of Prussia was the election of a German national parliament with which a small German constitution was to be drawn up.

In the German war that followed in the summer of 1866, Prussia and its allies were victorious. After the war, Prussia forced the defeated Austria in the Peace of Prague to state that the German Confederation had been dissolved . Prussia annexed several states and brought about the establishment of the North German Confederation , a federal state limited to northern Germany with 22 member states . The states first joined the North German Confederation in 1867 and then seamlessly joined the - largely identical - German Reich in 1870/71 .

rating

"The German Confederation was and is still considered by the overwhelming majority of historians to be out of date, blocking, reactionary and doomed to failure," said Jürgen Müller. Its inadequate constitution could not be reformed, and the structure would have prevented it from developing into a nation state (structuralist approach). In research, however, there was also some rudimentary reassessment of the federal government and an interest in the reform debates. As a result, the flexible basic federal laws did not stand in the way of reform. Rather, it was due to the anti-liberal federal policy of the great powers (incidental approach). Some historians, not least from Austria, saw the federal government as a welcome alternative to the nation state. Some, on the other hand, see the German Confederation as a forerunner of the supranational order of the 20th century (such as the United Nations ), which Müller rejects as excessive.

According to Ernst Rudolf Huber , the reform attempts did not fail because of the principle of unanimity. As long as Austria and Prussia worked together, they still achieved resolutions by the Bundestag, even against the resistance of medium-sized and small states. "A unanimous Austrian-Prussian federal reform proposal between 1848 and 1866 might have led to initial contradictions from one or the other medium-sized state, but in the end to a unanimous decision."

If the German Confederation had received a national representation at the beginning, it would have become a federal state at some point with the same competencies. Until 1866 Austria ensured that the federal government remained a federation by preventing a “direct federal organ of the whole state”. In constitutional reality, Austria and Prussia were more or less independent states. The German Confederation could only wage war as a Prussian, Austrian or Austro-Prussian war. Huber: “The Austro-Prussian dualism was the institutional and factual guarantee of the confederate character of the German federal constitution. As soon as the dualism ceased, the way to the state was free. "

See also

literature

- Jürgen Müller: German Confederation and German Nation 1848–1866 . Habil. Frankfurt am Main 2003, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005.

supporting documents

- ^ Michael Kotulla : German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934). Springer, Berlin 2008, pp. 329/330.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934). Springer, Berlin 2008, pp. 355-357.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume I: Reform and Restoration 1789 to 1830 . 2nd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1967, pp. 594/595.

- ^ Jürgen Müller: German Confederation and German Nation 1848–1866 . Habil. Frankfurt a. M. 2003, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, pp. 34/35.

- ^ Heinrich Lutz: Foreign policy tendencies of the Habsburg monarchy from 1866 to 1870: "Re-entry in Germany" and consolidation as a European power in the alliance with France. In: Eberhard Kolb (Hrsg.): Europe before the war of 1870. Power constellation - areas of conflict - outbreak of war. R. Oldenbourgh, Munich 1987, pp. 1-16, here pp. 2/3.

- ↑ Jürgen Angelow: The German Confederation . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2003, pp. 20–22.

- ↑ Jürgen Angelow: The German Confederation . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2003, p. 93.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, pp. 262/263.

- ↑ For example in 1859 during the Sardinian War, see Ernst Rudolf Huber: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 262/263.

- ^ Andreas Kaernbach: Bismarck's concepts for reforming the German Confederation. On the continuity of the politics of Bismarck and Prussia on the German question. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1991, pp. 27/28.

- ↑ Johan Christiaan Boogman: Nederland en de Duitse Bond 1815-1851 . Diss. Utrecht, JB Wolters, Groningen / Djakarta 1955, pp. 5-8.

- ↑ Johan Christiaan Boogman: Nederland en de Duitse Bond 1815-1851 . Diss. Utrecht, JB Wolters, Groningen / Djakarta 1955, p. 18 f.

- ^ Jürgen Müller: German Confederation and German Nation 1848–1866 . Habil. Frankfurt 2003, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, pp. 35/36.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 42.

- ^ Jürgen Müller: German Confederation and German Nation 1848–1866 . Habil. Frankfurt 2003, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, p. 3.

- ^ Jürgen Angelow: From Vienna to Königgrätz. The Security Policy of the German Confederation in European Equilibrium (1815–1866). Munich 1996, pp. 258-261.

- ^ Jürgen Müller: German Confederation and German Nation 1848–1866 . Habil. Frankfurt 2003, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, pp. 38/39.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 588.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 588/589.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 589.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 599.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 600.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life . Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), p. 43.

- ^ Jürgen Müller: German Confederation and German Nation 1848–1866 . Habil. Frankfurt 2003, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, p. 59.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 901/902.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 917-919.

- ^ Jürgen Müller: German Confederation and German Nation 1848–1866 . Habil. Frankfurt 2003, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, pp. 56–57, 60.

- ^ Jürgen Müller: German Confederation and German Nation 1848–1866 . Habil. Frankfurt 2003, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, pp. 58, 61/62.

- ^ Jürgen Müller: German Confederation and German Nation 1848–1866 . Habil. Frankfurt 2003, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, pp. 65, 79.

- ^ Jürgen Müller: German Confederation and German Nation 1848–1866 . Habil. Frankfurt 2003, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, pp. 67, 77-79.

- ^ Jürgen Müller: German Confederation and German Nation 1848–1866 . Habil. Frankfurt 2003, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, pp. 84–87, 148.

- ^ Jürgen Müller: German Confederation and German Nation 1848–1866 . Habil. Frankfurt 2003, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, pp. 156–159.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 265.

- ^ Andreas Biefang: Political bourgeoisie in Germany 1857–1868. National organizations and elites (= contributions to the history of parliamentarism and political parties , vol. 102). Droste, Düsseldorf 1994, ISBN 3-7700-5180-7 , p. 431.

- ^ Andreas Biefang: Political bourgeoisie in Germany 1857–1868. National organizations and elites (= contributions to the history of parliamentarism and political parties , vol. 102). Droste, Düsseldorf 1994, ISBN 3-7700-5180-7 , pp. 432-434.

- ^ Andreas Biefang: Political bourgeoisie in Germany 1857–1868. National organizations and elites (= contributions to the history of parliamentarism and political parties , vol. 102). Droste, Düsseldorf 1994, ISBN 3-7700-5180-7 , pp. 227/228.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 382/383.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 383/384.

- ↑ Jürgen Angelow: The German Confederation . Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2003, pp. 134-136.

- ↑ Jürgen Müller: The German Confederation 1815-1866. Oldenbourg, Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-486-55028-3 , p. 52, p. 55-57.

- ↑ Jürgen Müller: The German Confederation 1815-1866. Oldenbourg, Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-486-55028-3 , pp. 55, 57-59.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume I: Reform and Restoration 1789 to 1830 . 2nd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1967, p. 593.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume I: Reform and Restoration 1789 to 1830 . 2nd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1967, p. 669.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume I: Reform and Restoration 1789 to 1830 . 2nd edition, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1967, p. 668.