Foundation of the North German Confederation

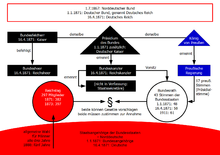

The establishment of the North German Confederation was a longer process in the years 1866 and 1867. It made Prussia with the allied countries in North and Central Germany by fusion a new joint state (federal state). The federal founding was preceded by the German War and the dissolution of the German Confederation founded in 1815 . The North German Confederation was not the legal successor of the German Confederation , but many elements of a long federal reform debate came into play when the federal government was founded.

The reform plan of June 10, 1866 , which Prussia had presented for a new small Germany , can be seen as a starting point for the foundation . In the summer of 1866 it decided that Prussia could only found a federal state in northern Germany - partly because of the opposition from France. Conceptual approaches to a division of the German Confederation into north and south had already existed. In 1866/1867 it was open whether and when the southern German states would ever join.

The German War was essentially ended on July 26, 1866 with the preliminary peace in Nikolsburg . Austria recognized the dissolution of the German Confederation and that Prussia north of the Main had a free hand for territorial changes and a new "federal relationship". Prussia annexed several opponents of the war in northern and central Germany and forced the others to join a new league through the peace treaties. With the August treaties , Prussia also obliged its allies to found a federal government.

Otto von Bismarck , the Prussian Prime Minister, agreed on a draft constitution with the other governments. On February 24, the constituent Reichstag was opened - not an actual parliament, but a body that was only supposed to deliberate on the constitution. After the revision by the constituent Reichstag, the governments also approved the draft constitution and also had it adopted by the state parliaments. On July 1, 1867, the constitution of the North German Confederation came into force, and the federal organs were soon established.

prehistory

Small German and North German solution

When the German Confederation was founded in 1815, there were considerations to divide Germany de facto into a Prussian-led north and an Austrian-led south. In addition to the idea of division, another idea came up in the revolutionary year of 1848 : Prussia and the other states in northern and southern Germany would found a closer federation, a small German federal state. Austria, which with its many peoples could hardly join a federal state, was to be linked to the narrower federation by a further federation (so-called Gagern double federation ).

When Prussia wanted to set up the “ Erfurt Union ” in 1849/1850 , this federal state was initially thought of in small German. But the southern German states stayed away from him, so that Prussia would only have united the north. Ultimately, the North German Kingdom of Hanover and the Central German Kingdom of Saxony also boycotted this attempt at unification, despite the signing of the Three Kings Alliance in May 1849.

In 1866 the rivalry between Austria and Prussia came to a head. On June 10, 1866, Prussia's Prime Minister Bismarck proposed to the other German states to elect a small German federal parliament and to renew the federal constitution. Shortly afterwards, Austria applied to the Bundestag to mobilize the army against Prussia, and the German war broke out.

August Alliance

The expression "North German Confederation" appears for the first time in the preliminary peace of Nikolsburg on July 23, 1866, which became the basis for the actual peace agreement with Austria on August 23 . There a "closer federal relationship" is mentioned, which Prussia is allowed to enter into with its allies in northern Germany. What was meant was a federal state that goes beyond a confederation like the German Confederation. This closer federal relationship is referred to in the same paragraph with the expression "North German Confederation".

On August 18, 1866, Prussia and 15 other states signed the August Alliance, which other states joined. In the treaty, the alliance simply calls itself “alliance” and speaks of a “new covenant” that has yet to be established. A federal constitution should ensure the aims of the alliance. The only purpose of the treaty is a common defense policy, but the basis for the new federal relationship is the Prussian reform plan for the German Confederation.

The term North German Confederation can theoretically refer to the August alliance as well as to the federal state that received its constitution on July 1, 1867. Michael Kotulla speaks of the fact that the covenant gradually became contoured. In any case, the August alliance was only a temporary arrangement, limited to one year. It was not yet an alliance of states, but only prepared one.

Federal states

| Country | meaning | Federal decree of June 14 to mobilize against Prussia | Joined the August Alliance | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingdom of Prussia , enlarged by the annexations of 1866 | European superpower | declared for breaking the law, not voted | August 18, 1866 | Federal reform plan of June 10, 1866 as the basis for the August alliance |

| Kingdom of Saxony | Middle state | approval | October 21, 1866 (peace treaty with Prussia, joining the alliance) | former enemy of Prussia |

| Grand Duchy of Hesse | Middle state | approval | September 3, 1866 (peace treaty with Prussia, participation in the federal government) | Entry only for his province of Upper Hesse |

| Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin | North German small state | Rejection | August 21, 1866 (separate contract for participation in the federal government) | own contract, due to reservations of the state parliament |

| Grand Duchy of Saxony-Weimar-Eisenach | Thuringian small state | Rejection | August 18, 1866 | |

| Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz | North German small state | Rejection | August 21, 1866 (separate contract for participation in the federal government) | own contract, due to reservations of the state parliament |

| Grand Duchy of Oldenburg | North German small state | Rejection | August 18, 1866 | |

| Duchy of Brunswick-Lueneburg | North German small state | Approval, to Königgrätz in the Prussian camp | August 18, 1866 | Federal constitution not ratified by state parliament, as this is not necessary |

| Duchy of Saxony-Meiningen and Hildburghausen | Thuringian small state | approval | October 8, 1866 (peace treaty with Prussia, joining the alliance) | former enemy of Prussia |

| Duchy of Saxony-Altenburg | Thuringian small state | Rejection | August 18, 1866 | |

| Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | Thuringian small state | Rejection | August 18, 1866 | |

| Duchy of Anhalt | Central German small state | Rejection | August 18, 1866 | |

| Principality of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt | Thuringian small state | Rejection | August 18, 1866 | |

| Principality of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen | Thuringian small state | Rejection | August 18, 1866 | |

| Principality of Waldeck-Pyrmont | Central German small state | Rejection | August 18, 1866 | |

| Principality of Reuss older line | Thuringian small state | approval | September 26, 1866 (peace treaty with Prussia, joining the August alliance) | former enemy of Prussia |

| Principality of Reuss younger line | Thuringian small state | not agreed, to Königgrätz in the Prussian camp | August 18, 1866 | |

| Principality of Schaumburg-Lippe | North German small state | Consent despite lack of instructions from the envoy; to Königgrätz to the Prussian camp | August 18, 1866 | |

| Principality of Lippe | North German small state | Rejection | August 18, 1866 | |

| Free and Hanseatic City of Lübeck | North German city-state | Rejection | August 18, 1866 | |

| Free Hanseatic City of Bremen | North German city-state | Rejection | August 18, 1866 | |

| Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg | North German city-state | Rejection | August 18, 1866 |

International situation

Despite the designation of the German War , other states were also involved in the conflict in the summer of 1866. This applies above all to the young nation-state of Italy , which wanted to liberate the last “unredeemed” areas and therefore had concluded an alliance with Prussia . Italian troops also took part in the armed forces against Austria, militarily less successful than Prussia, but with the desired political consequences: Italy acquired the previously Austrian Veneto .

The French Emperor Napoleon III. had bet on an Austrian victory and bought a say in Germany's future in a secret treaty in return for French neutrality. In addition, Austria had promised French control over the Rhineland, which had been Prussian until then . There were no such specific agreements with Prussia, which is why Napoleon felt betrayed by the outcome of the war.

But Napoleon managed to limit the Prussian expansion to northern Germany (north of the Main line). This rule from Franco-Prussian talks was included in the (Austro-Prussian) Peace of Prague (Art. 4). In efforts to expand the North German Confederation, this turned out to be a potential mortgage from the time the federal government was founded. When the southern German states joined the federal government in 1870, Austria-Hungary might have objected to this. In fact, however, it officially recognized the new situation (December 25, 1870) because it was politically isolated and wanted good relations with the future German Reich.

Britain and Russia also remained neutral during the war. This was partly due to domestic political problems, and both powers saw no danger to themselves or the European equilibrium in a limited Prussian expansion. Russia protested against the Prussian annexations: some of the monarchs affected were related to the Russian Tsar dynasty . However, this had no lasting effects on the Prussian-Russian relationship.

Creation of the federal constitution

The timetable for the North German Federal Constitution was only described rudimentarily in the August Alliance. It was similar to the path to a constitutional agreement for the Erfurt Union, but it was more complicated. On the one hand, this was due to the fact that the August alliance did not yet have a concrete draft constitution. On the other hand, the states were unsure whether the state parliaments had to approve the federal constitution.

Draft constitution

The allied governments, i.e. the state governments of the alliance partners, appointed representatives, as described in the August Alliance. The Prussian plenipotentiary, for example, was the Prussian Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Otto von Bismarck. Bismarck had several drafts of the constitution submitted to him.

Max Duncker was an old liberal and a former member of the Frankfurt National Assembly . His unitarian draft provided for almost unlimited legislative competence for the federal government and a collegial government, the states would have received a forum in a weak Federal Council. Every country should have the same number of votes in the Federal Council. This draft was too parliamentary for Bismarck and did not give Prussia enough weight.

Oskar von Reichenbach was a Greater German Democrat and wanted to abolish the Prussian Landtag in order to prevent Prussian hegemony. The king should appoint a responsible minister.

Hermann Wagener from the conservative Prussian Volksverein wanted to strengthen the Prussian king. As the “King of Northern Germany”, he was to appoint ministers responsible for him. It should be involved in legislation on an equal footing with the Reichstag and a Princely Congress . The Reichstag was to have few powers. Bismarck was bothered by the fact that, according to Wagener, the other states should join a Greater Prussian state, which would have become the "Kingdom of Northern Germany". That would not have been attractive either for the other northern German states or for the southern Germans who will hopefully join later. Christoph Vondenhoff: "Wagener's draft showed how far Bismarck had already moved away from his political home, Prussian conservatism."

Robert Hepke was an official in the Prussian Foreign Ministry. In his opinion, Prussia should exercise the executive as the presidential power. A Bundestag was responsible for preparing the laws. It should be composed of representatives of the individual states that would have formed federal technical commissions. Prussia would have presided over the Bundestag. In contrast, the Reichstag would have had only weak powers.

Bismarck found these drafts too centralistic or contradicting his image of the state and society, even though he was certainly influenced by them. Vondenhoff: "The connection of the forces effective in German constitutional life to a state-supporting whole resembled a circle quadrature." The result would be "beyond the traditional concepts of federal state and confederation".

The central stone of the new federation would be a federal council that assured the member states of codetermination. For this he wrote down the strong position of Prussia and its king, including the monarchical principle, in the constitution. The generally elected Reichstag was in keeping with German nationalism. The Federal Council and the Reichstag resulted in a balance of power that neutralized parliamentarianism.

Bismarck presented his own draft to the other representatives of the allied states. They discussed it from December 1866 to February 1867. After sometimes heated discussions, but rather less significant changes, they had agreed on a draft text. The draft was presented to the constituent Reichstag on March 4th .

Constitutional Agreement

While the plenipotentiaries were still deliberating, the state parliaments of the allied states enacted identical electoral laws based on the Frankfurt Reich Election Act. Thanks to these electoral laws, the constituent Reichstag could be elected.

This constitutional body met from February 24 to April 16, 1867. During this time, it discussed the draft of a federal constitution. He decided on several changes to the draft, some of which were very significant. Bismarck made it clear which changes were unacceptable to the governments. The constituent Reichstag, however, at least enforced a strengthening of parliament and the federal authority in general. In addition, the new federation received a responsible minister, the Federal Chancellor ( Lex Bennigsen ).

On April 16, a majority approved the amended draft constitution. The agents joined him on the same day. To be on the safe side, the state parliaments were then voted on. Only Braunschweig considered this unnecessary, as the state parliament had already approved the electoral law. The corresponding state resolutions were published in June.

There are very different opinions in research about the Federal Constitution, which later became essentially unchanged to the Reich Constitution . One direction thinks that the liberally dominated constituent Reichstag has almost completely implemented its ideas, another sees the winner in Bismarck, who was very satisfied with the amendments made by the constituent Reichstag. Some see the constitution as a typical or typical German constitutionalism , an independent type of constitution that reconciled absolutism and parliamentarism. Others see the constitution as a transitional step from monarchy to democracy , with elements atypical for constitutionalism such as the head of state. The constitution was also described as semi-constitutional or tailored entirely to Bismarck, so that it defies common divisions.

"Revolution from above"

In terms of form, the founding of the North German Confederation was not a revolution, because the princes and the people accepted that the founding states would lose their sovereignty. Basically, however, the establishment was a revolution because the constitutional state has fundamentally changed. The governments of the founding states carried out a “revolution from above”, the people and the parties from below. With the foundation, new, original law was created.

In constitutional law it was explained in different ways how the federal government came about. It could have been brought into being by the 23 state legislators. So said Paul Laband that only the publication laws were established in each country the federal government. Everything before that, like the August alliance or the resolution of the constituent Reichstag, was only a preparation for it. However, the states could only legislate for their own area and they could choose to join a federation. This leaves the question of who founded the federal government.

Furthermore, it was not enough to explain the founding of the federal government through a state treaty theory. By international treaties one could establish a confederation like the German Confederation, but not a nation state. This required the approval of the people or a representative body. Karl Binding and others therefore developed a theory of the constitutional agreement. In the constitutional agreement in the constitutional monarchy , the prince on the one hand and the parliament on the other hand agreed on a constitution. What was special about the founding of the North German Confederation was that the monarchical constitutional partner was not a single prince, but a multitude of princes or states.

To make matters worse, the governments of the individual states were bound by state law. They could not convene the constituent Reichstag on their own, but let the state parliaments pass the electoral laws. After the agreement between the governments and the Reichstag, a second agreement was required: because the federal constitution had consequences for state law , it also needed confirmation by the state parliaments. So it was a double constitutional agreement.

Law alone, pure normativity, was not enough for the foundation of the federal government, just as little as pure rule, pure facticity. It was significant that in 1867 (unlike 1848/49) there was a center of power like the Prussian state, the will of the nation to unite, a statesman like Bismarck, etc. The federal state of 1867 did not actually come about because a constitutional charter constituted judicial organs , but by actually exercising their power of rule. However, that was not enough. Ernst Rudolf Huber states: “Power is the prerequisite for the state, but it is not the state. [...] Power is not the cause of law; the law is not the result of power. The unifying bond through which power and law are united to form the whole of a new state is the idea that finds its reality in the new state. ”This idea has been the idea of the nation since the French Revolution .

Establishment of federal bodies

King Wilhelm as the holder of the Federal Presidium could not become active as a federal body as long as there was no Federal Chancellor to countersign his actions . The installation of Bismarck as Federal Chancellor was the first state act in the North German Confederation. This happened on July 14, 1867.

One problem was that the appointment of the Federal Chancellor was also an act that required a countersignature. But there was still no Federal Chancellor for that. In Huber's view, Bismarck should have countersigned himself because he was authorized to countersign through his candidate status. The moment Bismarck would have signed, he would have become the office holder and thus entitled to countersign. In fact, however, two Prussian ministers countersigned on July 14, although there was no legal basis for this in either Prussian or federal law.

After that, the other two highest federal bodies could be brought into being:

- The allied governments appointed their plenipotentiaries to the Federal Council . The Federal Chancellor, the constitutional chairman of the Federal Council, was then able to convene a constituent meeting of the Federal Council.

- King Wilhelm, as the holder of the Federal Presidium, had an ordinary Reichstag elected . On September 10th, he opened the elected Reichstag with a speech from the throne.

Thanks to the existence of the Federal Council and the Reichstag, it was now possible, among other things, for federal laws to be passed.

References to the German Confederation

The German Confederation from 1815 to 1866 had no legal successor . The North German Confederation was a pure re-establishment and also of different nature: Instead of a confederation of states with federal features, it was a federal state with federal features.

Nevertheless, the North German Confederation was part of a decades-long tradition of discussion about reforming the German Confederation . The draft constitution, for example from the years 1848/1849, was still accepted in the 1860s . Bismarck's reform plan of June 1866 (for the German Confederation) had roughly anticipated the North German Confederation. The centerpiece of the plan was a national parliament, elected according to the Frankfurt Reich Election Act of 1849. The national electoral laws for the North German Reichstag corresponded to that law almost to the word.

Further references between the German Confederation and the North German Confederation can be found in the Federal Constitution:

- The Federal Council of the North German Confederation was modeled on the Bundestag of the German Confederation , or the Princes' College of the Erfurt Union. The connection to a familiar body facilitated the transition from the confederation to the federal state.

- Expressions such as “ Federal Presidium ”, “President's Voice” and “ Federal General ” in the constitution of the North German Confederation come from the usage of the language from the time of the German Confederation.

- The distribution of votes in the Bundesrat is determined in the constitution of the North German Confederation (Art. 6). The model for this was expressly the plenary session of the former Bundestag.

- When the southern German states joined the North German Confederation, the remaining federal state received a " Constitution of the German Confederation ". However, this constitution of January 1, 1871 already gave the nation-state the name "German Empire".

The Bundestag of the German Confederation dealt with numerous individual topics in committees. Some materials were prepared over many years so that the North German Confederation could quickly cast them into North German federal laws. Jürgen Müller takes as an example, among other things, the standardization of weights and measures: In the German Confederation there was an effort to introduce the metric system . By June 14, 1866, 16 states had agreed to adopt the draft federal commission. After the end of the union, on August 17, 1868, the North German order of weight and measure came into being . She explicitly referred to the draft from the time of the German Confederation and adopted it almost unchanged.

See also

supporting documents

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, pp. 491/492.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 527. Kotulla points out that the Peace of Prague could only bind the contracting parties, but not the southern German states.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 491.

- ↑ Christoph Vondenhoff: Hegemony and balance in the federal state. Prussia 1867–1933: History of a hegemonic member state. Diss. Bonn 2000, Shaker Verlag, Aachen 2001, pp. 28–31.

- ↑ Christoph Vondenhoff: Hegemony and balance in the federal state. Prussia 1867–1933: History of a hegemonic member state. Diss. Bonn 2000, Shaker Verlag, Aachen 2001, pp. 31-33.

- ↑ Christoph Vondenhoff: Hegemony and balance in the federal state. Prussia 1867–1933: History of a hegemonic member state. Diss. Bonn 2000, Shaker Verlag, Aachen 2001, p. 33.

- ^ Overview by Hans-Peter Ullmann: Politics in the German Empire 1871–1918. 2nd edition, R. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2005, pp. 72/73.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 671.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 675.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 677.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 677/678.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 679/680.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 668.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 668.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 505.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm . 3. Edition. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 651 .

- ↑ Hans Boldt: Erfurt Union Constitution . In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. Böhlau, Cologne [u. a.] 2000, pp. 417-431, here pp. 429/430.

- ↑ Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional Law 1806-1918. A collection of documents and introductions. Volume 1: Germany as a whole, Anhalt states and Baden , Springer, Berlin [u. a.] 2006, p. 197.

- ^ Jürgen Müller: German Confederation and German Nation 1848–1866. Habil. Frankfurt am Main 2003, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, p. 451.