Constitution of the German Confederation

The Constitution of the German Confederation (or November Constitution ) was the constitution of the German nation-state ( Germany ) at the beginning of 1871. It was a revised version of the constitution of the North German Confederation ; it is not to be confused with the basic federal laws of the German Confederation founded in 1815 .

In the constitution of the German Confederation, provisions were included that the North German Confederation had agreed with the acceding southern German states: with Baden and Hessen-Darmstadt , but not yet Bavaria and Württemberg . The constitution appeared on December 31, 1870 in the Federal Law Gazette of the North German Confederation and came into force on January 1, 1871. On April 16, it was replaced by a newly revised Imperial Constitution , which was then in effect until the end of the German Empire in 1918.

A distinction must be made between:

- The constitution of the North German Confederation (North German Federal Constitution, NBV) of April 16, 1867. It came into force on July 1, 1867.

- The “Constitution of the German Confederation” as a text that was initially attached to one of the November treaties, namely the agreement between the North German Confederation and Hessen-Darmstadt and Baden.

- The constitution of the German Confederation (German Federal Constitution, DBV) as the constitutional text that appears in the Federal Law Gazette on December 31, 1870. The constitution itself gives the federal state, despite its title, the name " German Empire ". It came into force the following day. It is also called the “November Constitution”.

- The constitution of the German Empire of April 16, 1871. It is usually meant when the " Bismarckian Reich constitution " (BRV or RV) is mentioned.

The political system described remained the same in all four texts or three constitutions. Above all, names and provisions relating to the accession of the southern states, such as the number of votes in the Federal Council, were changed. However, this was carried out very inconsistently, so that the constitutional historian Ernst Rudolf Huber called the constitution of January 1, 1871 a "monster".

The constitution represents a step in the transition from the North German Confederation to the German Empire . In the corresponding steps, no new state was founded, but the admission of southern German states into the North German Confederation was regulated. Article 80, which was not incorporated into the constitution of April 16, 1871, was of permanent importance. Through him, the north German federal laws largely also applied to the new member states in the south.

Emergence

November contracts

The constitution of the North German Confederation came into force on July 1, 1867. It provided in Art. 79 sentence 2:

- "The entry of the southern German states or one of them into the Federation takes place on the proposal of the Federal Presidium by way of federal legislation."

In the autumn of 1870, the North German Confederation and the southern German states of Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden and Hesse-Darmstadt agreed on this entry (accession). However, there was disagreement among the southern German states about the terms of accession. Sometimes they tried to obtain exemptions for themselves (" reservation rights "). That is why there were several "November contracts" instead of a common document for joining the North German Confederation.

Baden was ready to simply join (for example on the occasion of the Lasker interpellation ), while the other southern states preferred to see a new establishment. Federal Chancellor Otto von Bismarck responded to these sensitivities for political reasons, so that the November Treaties actually spoke of a “new foundation” or “foundation” of a “German Confederation”. However, under constitutional law , it could only be about accession, since the North German Federal Constitution did not provide for self-dissolution. Michael Kotulla : "In contrast to the founding of the North German Confederation, that of the German Confederation or Reich was not a new creation, but only a reform of the North German Confederation."

An appendix entitled “Constitution of the German Confederation” belonged to the Baden-Hessian treaty, that is, to the treaty that the North German Confederation signed with Baden and Hessen-Darmstadt on November 15, 1870. The treaty also provided for some transitional rules, for example the tax revenue for the army went into the coffers of Baden and Hesse before January 1, 1872.

In the contract with Bavaria (November 23), Article 1 stated:

- “The states of the North German Confederation and the Kingdom of Bavaria conclude a perpetual union, which the Grand Duchy of Baden and the Grand Duchy of Hesse have already joined for their territory south of the Main and to which the Kingdom of Württemberg is likely to join.

- This union is called the German Confederation. "

In addition, the contract did not present a new constitutional text and did not refer to the text from the Baden-Hessian treaty. “Amazingly,” said Kotulla, the treaty determined the North German Federal Constitution as the basis and then described the constitutional changes to be made . The content of the 26 paragraphs to be changed, however, almost all corresponded to the text from the Baden-Hessian treaty. There were also reservation rights for Bavaria. The treaty made it appear as if Bavaria and the North German Confederation, without the other states, had undertaken an overall revision of the constitution. Bismarck allowed Bavaria to present itself one last time as the leading power in southern Germany.

The treaty with Württemberg (November 25th) was in turn an actual accession treaty. Württemberg thus expressly joined the constitution from the Baden-Hessian treaty. In addition, the treaty regulated the consequences for Württemberg, such as the number of Württemberg Federal Council votes and the special regulation for post and telegraphy, which Bavaria also enjoyed.

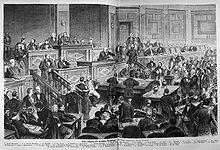

Parliamentary approval

However, these three treaties (as well as some additional protocols and conventions) had yet to be ratified. The North German Confederation concerned changes to the constitution. The Federal Council approved the Baden-Hessian treaty and the Bavarian treaty on December 9, the Reichstag on December 10.

Although the wording of the constitutions of the southern states was not changed, the accession meant that the southern states lost important powers. The legislative bodies of the southern states also had to agree. The parliaments in Baden, Hesse and Württemberg accepted the treaties in December. In Bavaria, on the other hand, approval was only announced on January 30, 1871. The Bavarian king decreed that the ratification would take effect retrospectively at the beginning of the year. Bavaria's membership of the German federal state was initially pending, but its entry also took effect on January 1, 1871.

"Kaiser" and "Reich"

The terms federal and federal presidium suggested the following idea, according to Ernst Rudolf Huber: The King of Prussia held the functions of the highest federal executive. The individual states seemed to be subject to Prussian violence. That could hurt the feelings of the southern states, especially Bavaria. It was different when there was talk of an empire and an emperor. The presidential powers (for the Prussian king) then appeared as imperial powers. The feelings of the southern states and their princes were also taken into account through the " Kaiserbrief ". In it the Bavarian king called on the Prussian king on behalf of his fellow princes to accept the title of emperor.

The expression Reich was popular in various political camps and with both major denominations: In the sense of historicism , the expression built a bridge into the past. The National Liberals demanded the expression as a sign of unity, while the Bavarian patriots on the contrary in "Empire" the tradition of German liberty, the Reichspartikularismus saw the independence of the individual states. For the liberals and the democratic left, “Kaiser and Reich” were “a subsequent justification for the great bourgeois revolutions and the imperial constitution of 1849 that failed in it ” (Huber).

By making concessions to such feelings, Bismarck wanted to facilitate the approval of the November treaties for the South Germans. As early as the beginning of 1870, Bismarck's “ Kaiserplan ” was sober about consolidating unity. He had nothing but ridicule for the enthusiastic Kaisertümelei of some princes and also of the Prussian Crown Prince.

On December 9, 1870, the Reichstag of the North German Confederation adopted the constitutional text and some provisions of the November treaties. The Federal Council followed on the same day. The Federal Council in turn, in agreement with the southern German governments, decided to change the introductory formula and Article 11 in order to introduce the terms Kaiser and Reich. The Reichstag approved this on December 10th (with only six votes against). On December 18, a deputation from the Reichstag asked the Prussian king to accept the dignity of emperor. King Wilhelm immediately accepted the request. However, the resolutions of the Bundesrat and Reichstag were not properly published; instead, they only appear in the Reichstag minutes. The Federal Chancellery solved the problem by only modifying the preamble and Article 11 in the constitutional text for the Federal Law Gazette.

This was followed by an imperial proclamation on January 18, 1871, which was placed on the anniversary of the Prussian royal coronation in 1701. On this occasion, King Wilhelm and the other princes confirmed an emperor's dignity, which the Prussian king had had since January 1, 1871 under the new constitution. Kotulla: "However, the symbolic character of this act remains, which was certainly considered the birth of the empire in the public consciousness, but was meaningless under constitutional law."

content

The official text of the "Constitution of the German Confederation" appeared on December 31, 1870 in the Federal Law Gazette. This was the text of the Baden-Hessian treaty. The terms “Kaiser” and “Reich”, as decided by the Federal Council and the Reichstag, were also included. However, they were only in the preamble or in Art. 11 and not yet in the other places where the term “Federation”, “Federal Presidium” or “ Federal General ” was mentioned. The preamble to the constitution read:

- "His Majesty the King of Prussia in the name of the North German Confederation, His Royal Highness the Grand Duke of Baden and His Royal Highness the Grand Duke of Hesse and near Rhine for the parts of the Grand Duchy of Hesse south of the Main have concluded an eternal alliance for the protection of the federal territory and of the law valid within the same, as well as for the care of the welfare of the German people. This union will be called the German Empire and will have the following constitution. "

Most of the innovations that had been agreed with Bavaria and Württemberg were missing. These two countries do not appear in the preamble, in the definition of the federal territory (Art. 1) and in the distribution of votes in the Bundesrat (Art. 6). Württemberg had ratified the treaties at the end of December. At least with regard to this country, the new federal constitution was already out of date.

Most of the points in the Bavarian treaty, however, were identical to those in the Baden-Hessian text. They appear accordingly in the federal constitution:

- The catalog of competencies, i.e. the list of what the federal government is allowed to enact laws, has been expanded to include the press and associations (Art. 4)

- The Federal Presidium (the Kaiser) was given the right to veto certain changes in the law (Art. 5, Paragraph 2)

- The competencies of the Federal Council have been tightened (Art. 7)

- It was made clear that for matters that did not affect all member states, only the corresponding votes in the Bundesrat and Reichstag counted

- The Federal Council had to approve declarations of war by the emperor (Art. 11 Para. 2)

- The transfer of state officials to the federal service was regulated (Art. 18)

- The federal execution was defused

- The free port area was rewritten (Lübeck had already joined the north German trading area in 1868)

- Changes in customs and trade

- Changes to the postal and telegraph systems

- Changes to the consular system

- Changes on conscription

- The accession clause for the southern German states (Art. 79 NBA) has been generalized for German states that are not yet part of the federal government

- List of those laws of the North German Confederation that became laws of the German Confederation at a specific point in time (Art. 80) and thus also applied in the new southern German states

- The "North Germans" became the "Federal Members" (Art. 3, 57, 59)

Changes in Bismarck's Imperial Constitution

On February 1, Federal Chancellor Bismarck pointed out to the Kaiser that the constitution had to be editorially revised. The new Reichstag was elected on March 3rd. On March 23, immediately after the election of the President of the Reichstag, Bismarck submitted a draft constitutional amendment. The Center Party tried to push through changes in content on this occasion. She called for a catalog of fundamental rights , but only with those fundamental rights that the Catholic Church would like . The liberal parliamentary groups rejected the request, and only the new editorial action requested by Bismarck and the Federal Council took place.

The new Imperial Constitution, known as Bismarck's Imperial Constitution , came into force on April 16, 1871, on May 4, 1871, replacing the November constitution. It had only been valid for about four months.

On this occasion, most of the designations in the constitution were adapted to the new state name and the imperial title. Kaiser Wilhelm wanted to proceed particularly consistently and, for example, turn the "Bundesrat" into a "Reichsrat". But Bismarck emphasized that the name Bundesrat refers to the representation of the individual states. The “Federal Chancellor” also became a “ Reich Chancellor ”, but several expressions remained the same (such as “Federal territory”). The previous “Federal Army” appeared in the new constitution sometimes as “Reichsheer”, sometimes as “ German Army ”, in Article 62 even both names appear.

Bavaria and Württemberg have now been included in the preamble and in the definition of the federal territory. They also received their Federal Council votes and the number of members of the Reichstag was adjusted. There was also an eighth Federal Council Committee (for foreign affairs) with special regulations for Bavaria, Saxony and Württemberg; unlike in the Bavarian treaty, however, also with representatives of other states. Further exemptions for individual southern states were also included in the constitution.

However, there was still constitutional law that was not in the constitutional document. These include the regulations on Alsace-Lorraine and the provisions from the final protocols to the three actual November contracts and from the Bavarian treaty and the military convention with Württemberg. These provisions concerned reservation rights which the individual states had negotiated for themselves. They were still valid constitutional law. A part of the November Constitution also had permanent constitutional status: Article 80 with its list of the North German federal laws that became Reich laws.

See also

Web links

supporting documents

- ^ So with Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 747.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, p. 757.

- ↑ Michael Kotulla : German Constitutional Law 1806-1918. A collection of documents and introductions. 1. Volume: All of Germany, Anhalt States and Baden. Springer, Berlin [a. a.] 2006, p. 231.

- ↑ Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional Law 1806-1918. A collection of documents and introductions. 1. Volume: All of Germany, Anhalt States and Baden. Springer, Berlin 2006, pp. 231, 246.

- ↑ Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional Law 1806-1918. A collection of documents and introductions. 1. Volume: All of Germany, Anhalt States and Baden. Springer, Berlin 2006, pp. 231/232.

- ↑ Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional Law 1806-1918. A collection of documents and introductions. 1. Volume: All of Germany, Anhalt States and Baden. Springer, Berlin 2006, pp. 232/233, 236.

- ↑ Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional Law 1806-1918. A collection of documents and introductions. 1. Volume: All of Germany, Anhalt States and Baden. Springer, Berlin 2006, p. 240.

- ↑ Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional Law 1806-1918. A collection of documents and introductions. 1. Volume: All of Germany, Anhalt States and Baden. Springer, Berlin 2006, pp. 244/245.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, p. 741.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, p. 767.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, p. 738.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, pp. 746/747.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, p. 757.

- ↑ Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional Law 1806-1918. A collection of documents and introductions. 1. Volume: All of Germany, Anhalt States and Baden. Springer, Berlin 2006, p. 243.

- ↑ Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional Law 1806-1918. A collection of documents and introductions. 1. Volume: All of Germany, Anhalt States and Baden. Springer, Berlin 2006, pp. 247/248.

- ^ After Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional Law 1806-1918. A collection of documents and introductions. 1. Volume: All of Germany, Anhalt States and Baden. Springer, Berlin 2006, pp. 248/249.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, p. 758.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, p. 757 f.

- ^ After Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional Law 1806-1918. A collection of documents and introductions. 1. Volume: All of Germany, Anhalt States and Baden. Springer, Berlin 2006, pp. 250/251.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, p. 759.