Bismarck's Imperial Constitution

As Bismarckian Reich Constitution is the Constitution of the German Empire referred on 16 April 1871st It originally emerged as the constitution of the German Confederation of January 1, 1871 in a revised version from the North German Federal Constitution drawn up in 1867 . The official title was now Constitution of the German Empire (RV 1871); it was valid for almost fifty years with no major changes.

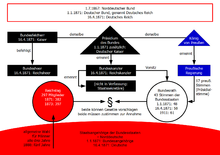

In the Federal Council , the highest organ of the state of the German Empire , which had states represented . The Presidium of the Federation was held by the King of Prussia , who bore the title of ' German Emperor '. The Kaiser appointed the Reich Chancellor , who presided over the Bundesrat, directed its affairs and was the only Reich Minister in charge . The Chancellor thus became one of the main bodies in the political system, both behind the scenes and in the public eye. Imperial Lawsneeded the approval of two organs, namely the Federal Council and, in addition, the Reichstag . The Reichstag was elected every three years and from 1885 every five years, according to universal suffrage for men.

On August 14, 1919, Bismarck's constitution was repealed by Article 178 of the Weimar constitution .

Come about

The Bismarck Reich constitution emerged from the North German Federal Constitution (NBV) of 1867, when the southern German states united with the North German Confederation in 1870 . On November 15, 1870, the North German Confederation, Baden and Hesse signed a treaty establishing the German Confederation and establishing the Federal Constitution. On November 23, Bavaria joined the German Confederation. On November 25, Württemberg declared its accession. On December 8, 1870 , the North German Reichstag ratified the four treaties. The state parliaments of Baden, Hesse and Württemberg ratified the treaties in December 1870; the state parliament of Bavaria ratified the accession treaty on January 21, 1871. On December 10, 1870, the Reichstag also accepted the Federal Council's proposal that the German Confederation should be named German Empire and the presidential power should be given the title of imperial . All these changes are summarized in a text that was published in the Federal Law Gazette on December 31, 1870 . This text still spoke of the constitution of the German Confederation , which bears the name "German Reich". This constitution came into force on January 1, 1871.

On the basis of this constitution, a new Reichstag was elected by the people on March 3, 1871 , which approved a revised constitutional text on April 14. The law concerning the constitution of the German Empire of April 16, 1871 summarized all founding and accession treaties and replaced the designation “Bund” with “Reich”; to emphasize federalism , the term “Bundesrat” remained. The amended constitutional text came into force on May 4, 1871.

The designation of RV 1871 as Bismarck's Reich constitution is justified. The various preliminary drafts of the North German Federal Constitution by Maximilian Duncker , Robert Hepke , Karl Friedrich von Savigny and Lothar Bucher were commissioned by Bismarck and revised in each case.

Structure and structure of the constitution

The German Reich was a federal state in the sense of a federal state as a whole; the states were also called states . It was a semi-parliamentary monarchy with strong, conservative Prussian supremacy. The monarch was not only head of state ; he also had many powers of government, and the people of the state were involved in legislation through the Reichstag . The prelude to the constitution deliberately gave the misleading impression that the federation had only been agreed as a treaty between the federal princes, hence as a federation of states , and was not based on the constituent powers of the member states.

The constitution was divided into fourteen sections. The first section describes the composition of the federal territory. The strongest member state was Prussia with about two thirds of the total population. Sections 2–5 and 14 deal with government responsibilities and organs; Sections 6–13 with legislation and administration in special subject areas, e. B. Railways or Imperial Warfare. In Section 2, Reich Legislation, the jurisdiction of the Reich and member states is delimited and, at the same time, a distinction is made between legislation and Reich supervision by the Kaiser. In addition to state organization law , the relationship between citizen and state is also regulated. For example, the member states were required to grant members of other member states the right of immigration and the same civil rights as their own citizens.

There was no catalog of fundamental rights in the imperial constitution, but only in the constitutions of the member states. Not mentioned in the constitutional text, but taken for granted that administrative sovereignty lies with the member states and not with the Reich. When the German Confederation was founded in 1870, the authorities and administrative regulations in the individual member states were already in place. In contrast, the constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany expressly provides for the administrative sovereignty of the states. Section 3 regulates the participation rights of the member states in affairs of the Reich through the Bundesrat. Section 4 regulates the rights of the emperor and imperial chancellor.

Constitutional law outside the constitutional charter

The constitution of April 16, 1871 had come about in a tortuous way. In addition, the Reichstag and Bundesrat regulated some matters that were part of the substantive constitutional law through laws instead of through constitutional amendments. The constitutional lawyer Ernst Rudolf Huber lists:

- The regulations on Alsace-Lorraine and the colonies ;

- Article 80 of the constitution of January 1, 1871 as well as Article III § 8 of the Treaty with Bavaria and Article 2 No. 6 of the Treaty with Württemberg (these articles stipulated that specific north German federal laws also applied to southern Germany and thus became Reich laws);

- the final protocols to the November treaties for so-called reservation rights of southern German states as well as regulations on the imperial war system for Bavaria and Württemberg.

Huber criticizes this "fragmentation" because it is detrimental to the unity of the nation and the reputation of the constitutional charter. He expressly mentions the integration of Alsace-Lorraine, whose constitutional status was only regulated by simple laws.

Powers of the empire

Legislative competences of the empire

The constitution made a distinction between exclusive and competing legislation . Competing legislation meant that imperial laws took precedence over the laws of the member states, or, conversely, that laws of the member states were effective where no imperial laws opposed them. Exclusive legislation existed for constitutional amendments , the imperial budget, taking out loans and assuming guarantees, the strength of the army in peace , military spending, customs duties and consumption taxes, and emergency legislation . In other areas, the Reich had the right to compete legislation, mainly for matters to create uniform living and economic conditions and to facilitate trade and traffic in the federal territory, in particular freedom of movement , trade legislation , the system of measures , coins and weights, and the railway system.

The Reich was able to expand its legislative competence by means of the constitutional amendment. This was initially disputed on the grounds that only the federal princes who signed the treaty could dispose of a reduction in their responsibilities. Because the parliaments of the individual states approved the establishment, this view was not tenable. In 1874 the constitution was changed for the first time and the empire was also given legislative competence for the law of natural and legal persons , family law , inheritance law and property law .

Reich supervision

Where the Reich was responsible for legislation, it also had legal and technical supervision . Legal and technical supervision was exercised by the Reich Chancellery and the later Reich Offices. Reich officials were assigned to the authorities of the member states for customs duties and consumption taxes. The Federal Council decided on the detection of deficiencies by resolution. If the federal states did not comply with a complaint, the emperor could take coercive measures under the countersignature of the Chancellor.

administration

Since the states remained in charge of administration, they could in many cases determine the establishment of their authorities, the administrative procedure and the administrative regulations themselves. Domestically, there was therefore joint responsibility for the Reich and the federal states in many areas. This cooperative model was reinforced by the fact that the governments of the federal states exercised significant influence over the Reich legislation through the Bundesrat and also controlled the legal supervision of the Reich over the enforcement of Reich laws by the federal states through the Bundesrat.

The Reich set up some branches of administration without the express authorization of the constitution and created the associated administrative regulations, e.g. B. for the diplomatic service and the Reichstag administration. Such a competence by virtue of factual context was recognized.

A mixed but uniform administration existed for the post and telegraph system. The officials responsible for the local and technical areas remained state officials at the individual operations. Only the top officials and supervisors were Reich officials. Bavaria and Württemberg kept their own post and telegraph administrations, but were subject to the exclusive legislation of the Reich. The railroad administrations remained in the hands of the states. However, the Reich had authority over the railway administrations in certain areas, e.g. B. regarding the structural condition or the procurement of materials. In particular, the empire set a uniform rail tariff. The governments of the federal states were obliged to manage the German railways like a unified network. A special regulation applied to the railways in the Kingdom of Bavaria . Here the rights of the empire were limited to the enactment of uniform standards for the construction and equipment of the railways important for national defense .

The financial and tax administration remained in the hands of the states. Where the Reich had made use of its legislative competence for customs and taxation, it was able, by resolution of the Federal Council, to issue administrative regulations and provisions on the establishment of tax and customs authorities of the federal states. The voting rights of the Presidium had less weight in the decision-making process. After hearing the Federal Council Committee for Customs and Taxation, the Reich was able to send Reich officials to supervise the customs and tax authorities and their superior intermediate authorities.

Police and police law were retained in the member states. Only in the area of railway police law did the Federal Council pass in 1871 the railway police regulations of the North German Confederation for the entire federal territory as a general administrative regulation.

jurisdiction

The states had jurisdiction. The empire exercised jurisdiction only where the constitution expressly granted it to the empire. The Reich exercised criminal jurisdiction for crimes against the existence of the German Reich if they were to be qualified as high treason and treason matters. Initially, the higher appeal court of the three free and Hanseatic cities with its seat in Lübeck was responsible, from 1879 the newly established Reichsgericht in Leipzig. The imperial constitution allowed the reorganization of the entire judiciary, which was done comprehensively with the imperial justice laws of 1877, in particular the court constitution law . There were instance courts of the empire in the Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine , namely imperial district and regional courts as well as the imperial higher regional court in Colmar . Constitutional disputes between states were decided by the Federal Council, which could act like a state court. If there was no state court in a state, the Federal Council was responsible for constitutional disputes.

State organs

Federal Council

The Federal Council was the bearer of sovereignty and the highest state organ . It consisted of 58 representatives from the 25 states who did not have to be members of the government. The chairman of the Federal Council was the Chancellor appointed by the Kaiser, who also managed day-to-day business and drafted the draft resolutions. The Federal Council was not a council of princes, but the representation of the member states , which could bring the interests of the federal states into the exercise of the sovereignty of the empire. Like a second chamber, it was involved in the legislative process, in government tasks and in the judiciary .

The Federal Council participated in the legislation on an equal footing with the Reichstag. He had the right to initiate legislation, and every law required the approval of the Federal Council; so he had a real right of veto.

The Federal Council was able to issue the general administrative regulations necessary for the implementation of imperial laws and to make organizational decisions about the administrative authorities. As part of the Reich supervision of matters of uniform living and economic conditions throughout the Reich, the Federal Council was able to identify deficiencies in the administration of the individual federal states. In addition, like a state court, the Federal Council could decide public disputes between the states, as well as constitutional disputes in states that did not have their own state court. In order to be able to fulfill its extensive tasks, the Federal Council formed committees from its members, to which the necessary officials had to be made available.

The constitution stipulated the following weighted distribution of votes in the Federal Council:

| State | Votes in the Federal Council |

|---|---|

| Prussia | 17 votes |

| Bavaria | 6 votes |

| Saxony | 4 votes |

| Württemberg | 4 votes |

| Swimming | 3 votes |

| Hesse | 3 votes |

| Mecklenburg-Schwerin | 2 votes |

| Braunschweig | 2 votes |

| Saxe-Weimar | 1 vote |

| Mecklenburg-Strelitz | 1 vote |

| Oldenburg | 1 vote |

| Saxony-Meiningen | 1 vote |

| Saxony-Altenburg | 1 vote |

| Saxe-Coburg-Gotha | 1 vote |

| Stop | 1 vote |

| Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt | 1 vote |

| Schwarzburg-Sondershausen | 1 vote |

| Waldeck | 1 vote |

| Reuss older line | 1 vote |

| Reuss younger line | 1 vote |

| Schaumburg-Lippe | 1 vote |

| lip | 1 vote |

| Lübeck | 1 vote |

| Bremen | 1 vote |

| Hamburg | 1 vote |

| total | 58 votes |

A state that wanted to cast its vote had to appoint at least one proxy. He didn't have to be a member of the government. However, each state was allowed to appoint as many plenipotentiaries as it had votes. The votes of a member state could only be cast uniformly. The plenipotentiaries were bound by instructions from their federal states, unlike the members of the Reichstag, who were not bound by orders and instructions.

The Federal Council regularly made decisions with a simple majority. In the event of a tie, the “presidential vote” (the votes from Prussia) was decisive. Constitutional amendments could not come about against the will of Prussia, because 14 votes against (Prussia had 17 votes) were sufficient to reject a constitutional amendment. Bills on military and naval affairs, customs and excise duties as well as related administrative regulations and organizational decisions could be rejected with the presidential vote.

In 1911 the Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine received three votes. The imperial governor appointed the representatives of the Federal Council and gave them the instructions. These votes were not counted in support of Prussia's votes. In the case of constitutional amendments, the votes of Alsace-Lorraine were not counted on either side. The Prussian voices should not be increased by the fact that the King of Prussia as German emperor , the state power exercised in Alsace-Lorraine.

The Kaiser ("Presidium of the Federation")

The constitution emphasized the monarchical element . The King of Prussia held the presidium of the Confederation and, in accordance with Art. 11, was called the “German Emperor”. There was a real and personal union between the two offices. At the end of the First World War , there were plans to separate the two offices and, for example, to appoint an imperial regent. However, this would not have been possible without the constitutional amendment.

The emperor could not be held responsible for his administration; his person was inviolable. This principle contained in Article 43 of the Prussian Constitution of 1850 continued to apply to the Kaiser as an unwritten principle of the Imperial Constitution. The imperial constitution also did not oblige the emperor to take an oath to govern only in accordance with the constitution, as provided for in Article 54, Paragraph 2 of the Prussian constitution. However, he made a pledge to the Reichstag, even without obligation, to observe and defend the imperial constitution.

All government acts of the emperor had to be countersigned by the chancellor in order to be effective. With the countersignature, the Reich Chancellor took on responsibility, in an unclear formulation also towards the Reichstag. In the case of real acts that were not suitable for countersigning, such as speeches, handwriting and statements to the press, the approval of the Reich Chancellor had to be obtained beforehand. The countersignature did not apply to acts of military command and control .

Powers of the emperor as head of state

The Kaiser was head of state of the German Empire and represented the empire under international law . He concluded international treaties , alliance treaties and peace treaties for the empire . He needed the approval of the Federal Council for declarations of war . International treaties, unilateral declarations and real acts required the Reich Chancellor's countersignature to be effective. Contracts relating to subjects of Reich legislation or Reich supervision required the approval of the Bundesrat and the approval of the Reichstag to be effective. As the highest representative of the German Empire, the emperor also received and authorized the ambassadors.

Powers of the Emperor in Legislation

The emperor was responsible for drafting and promulgating the imperial laws in the imperial law gazette. Only he could appoint, open, adjourn and close the Reichstag and the Bundesrat, without whose consent no Reich law could come into force. During a legislative period he could only dissolve the Reichstag at the request of the Federal Council.

Government powers of the emperor

Without the consent of the Bundesrat and the Reichstag, the Kaiser appointed and dismissed the Reich Chancellor, who chaired the Bundesrat and directed the affairs of government. The emperor supervised the execution of the imperial laws; his objections to the law enforcement became effective with the countersignature of the Reich Chancellor. After authorization by the Federal Council, the emperor had the right to impose coercive measures on member states that did not fulfill their constitutional obligations. His orders became effective with the countersignature of the Reich Chancellor, who thereby also assumed responsibility for the Reichstag. This also applied to immediate rulings, for example real foreign policy files. The authorization of an interview in the English newspaper Daily Telegraph was presented to Reich Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow before the exit , who forwarded it to the Foreign Office, which made changes to it. The Kaiser also appointed the other Reich officials, employed the German consuls and supervised the consular affairs. The emperor was also the head of the post and telegraph administration.

Military powers of the emperor

In war and peace the emperor was entitled to command and command over the imperial army. In the event of a military attack on the Reich, the Kaiser could declare war on an attacker without the consent of the Federal Council, but with the countersignature of the Reich Chancellor. Acts of the imperial authority of command and command were effective without the Reich Chancellor's countersignature. On August 2, 1914, the emperor authorized the chief of the general staff to issue orders to the command authorities of the field army. All German troops were obliged to obey the orders of the emperor unconditionally. The emperor has the right to inspect the troops and to determine the structure of the army. He could not determine the strength of the army's peacekeeping presence and the level of military spending; this fell within the joint competence of the Federal Council and the Reichstag. The emperor was in command of the navy. The Federal Council and the Reichstag jointly determined their size and the cost of this.

Emergency powers of the emperor

If public security was threatened, the emperor could declare the state of siege for an unlimited period of time in the entire federal territory in war and peace, with countersignature of the Reich Chancellor, but without the consent of the Bundesrat and the Reichstag. The executive power was thereby transferred to the military commanders. The Prussian law on the state of siege was always considered to be part of the constitution, because the proposed state law on the state of siege did not come into effect. The law was never applied in peacetime, but a state of siege was declared throughout World War I. Due to the state of siege, political civil rights such as freedom of expression and freedom of assembly could be restricted at will.

Powers of the emperor in Alsace and Lorraine

The emperor exercised state authority in Alsace and Lorraine. Orders and decrees of the emperor required the countersignature of the chancellor to be effective. The Federal Council and the Reichstag also had the right to legislate for Alsace and Lorraine together.

Political significance of the imperial powers

The imperial powers went further than the name Presidium of the Federation suggested. In terms of power politics, it was extremely effective that the Kaiser could appoint and remove the Reich Chancellor and Reich officials, as well as that the Kaiser was entitled to command and command over the army and navy not only in the event of war but also in peace. He could always refuse to sign the Reich Chancellor's drafts, so that the government deal sought did not materialize. Between 1890 and 1908, Kaiser Wilhelm II exercised his office as a personal regiment and, despite persistent failures, endeavored in an autocratic manner to influence day-to-day political affairs. This possibility was laid out in the constitution: the necessary agreement could also be achieved by the emperor appointing personalities with little political need to shape the chancellor. The Reichstag could neither elect nor deselect the Chancellor, so that the power of government did not go back to the will of the people, but to the King of Prussia. It was not until the October reform of 1918 that the Reichstag was given the right to vote out the Reich Chancellor and was given responsibility for acts of imperial command and control of political importance. As a result, the power of government passed into the sovereignty of the people.

Reich leadership

Chancellor

The Reich Chancellor was chairman of the Federal Council and, as the only responsible minister of the Reich, headed the entire civil administration. Due to the meeting of the two offices, he was head of the highest Reich policy. The constitution did not provide for a council of ministers as a collegiate body; the state secretaries were not ministers but officials who received instructions from the chancellor. Bismarck feared that a government, rather than an individual, was subject to parliamentary control and the budgetary powers of the Reichstag. The term Reich Government was avoided. After the fall of Bismarck, the term Reichsleitung became established .

Reich offices

During the time of the North German Confederation, the state only had two highest authorities. The Foreign Office was the former Prussian Foreign Ministry, which was transferred to the federal government in early 1870. For everything else there was only the Federal Chancellor's Office, which was headed by State Secretary Rudolph von Delbrück and was renamed the Reich Chancellery .

Because of the complexity of the tasks outsourced Bismarck responsibilities of the Reich Chancellery subordinate in his imperial offices , which were conducted as supreme Reich authorities of state secretaries. 1873 was Reich Railway Office , 1876, the Office of the Postmaster General , from 1880 renamed Reichspostamt , 1877 Reichsjustizamt , 1879, the Reich Treasury and 1879, the chancellorship in which was Ministry of the Interior converted. The tasks of a personal office of the Reich Chancellor were transferred to the newly created Reich Chancellery . In 1889 the Reichsmarineamt was formed and in 1907 the Reichskolonialamt was created from the Foreign Office .

In addition, this diversification should limit Delbrück's position of power . The Act of Representation of 1878 made it possible for the Reich Chancellor to be represented in a specific department or in all of his areas of responsibility. The Reich Chancellor reserved the right to take over matters from the Reich Offices at any time.

In addition to these imperial offices headed by state secretaries, other higher imperial authorities emerged: in 1871 the audit office , 1872 the statistical office, 1874 the imperial debt administration , 1876 the imperial health department and the imperial bank , 1877 the patent and trademark office , 1879 the imperial court and 1884 the imperial insurance office .

Civil cabinet, military cabinet, naval cabinet

The emperor had the personal questions of the Reich officials and questions of internal politics and administration of the Reich dealt with by the Prussian civil cabinet , which thereby became the organ of the Reich. In the military field, imperial tasks were assigned to the Prussian military cabinet. In 1889 the Naval Cabinet was founded, which soon outgrew its original task of officer personnel matters for the Navy and thus came into conflict with the Reichsmarineamt and the Naval War Command . The cabinet system impaired the Reich Chancellor's accountability and reduced his sphere of influence.

Privy Council

A privy council was not provided for in the imperial constitution. Joint immediate lectures by the Supreme Army Command and the Reich Chancellor during the First World War, which took place under the direction of the Emperor, were so called. As an imperial command file, the results were binding for the Reich Chancellor, also with regard to overriding political issues that affected the Reich as a whole.

Parliament

The Reichstag was entitled to part of the classic parliamentary rights. In agreement with the Federal Council, it passed the Reich laws on matters for which the Reich was responsible. He had the right to initiate legislation. It was of great importance that the empire's budget had to be approved by a budget law. This also applied to the imperial navy. The Reichstag, by mutual agreement with the Bundesrat, set the peace-keeping strength of the army, the cost of which the federal states had to bear according to the number of residents. However, the Reichstag was able to approve the expenditure for the army, albeit not annually, but for a period of seven years, from 1881 five years. Income and expenditure of the empire were to be determined annually.

The MPs had a free mandate and, as representatives of the entire people, were not bound by instructions, unlike the Federal Council plenipotentiary. The mandate was an honorary post; the payment of salaries or compensation was excluded. This diet ban was lifted in 1906 after several attempts. Officials who were elected to the Reichstag did not have to let their office rest. The MPs enjoyed immunity. The negotiations in the Reichstag were public.

The general, equal, secret and direct suffrage corresponded to the suffrage of the Frankfurt National Assembly of 1849. It was also used in the 1867 Reichstag elections of the North German Confederation. However, it only applied to men aged 25 and over; the women's suffrage was introduced in Germany 1918/1919. There were also restrictions on men who lived on public poor relief.

The majority vote was voted right. If there was no absolute majority in the first ballot, a run-off election was held between the two candidates with the strongest vote. The constituencies of 1871 were not redistributed until the First World War, which meant that the rural counties with their more conservative votes were significantly over-represented. In the 1898 Reichstag election, for example, the SPD received 56 seats with a 27.2% share of the vote and the Center Party received 102 seats with a 18.8% share of the vote. The desired equality of counting of the votes was not given.

The Bismarckian constitution made no statements about the right to vote in the individual states. There there was usually no general and equal option, but rather a class suffrage or a plural suffrage . Social democrats and left-wing liberals invoked the model of the Reichstag suffrage when they advocated a general and equal election at the level of the individual states.

The Reichstag could neither elect nor deselect the Reich Chancellor, nor indict him in a constitutional court. It was only after the October reforms of 1918 that a Reich Chancellor needed the confidence of the Reichstag. This was also common in other European countries. If the parliamentary principle (the appointment of the head of government at the request of parliament) did not prevail in Germany, it was because there was no sustainable majority in the Reichstag.

Alongside the emperor, the Reichstag was the Unitarian element in the otherwise strongly federal imperial constitution . The Reichstag was elected by general election for three years, from 1885 after a constitutional amendment for five years. Even during a legislative period, the Federal Council was able to dissolve the Reichstag with the consent of the Kaiser and Reich Chancellor.

Fundamental rights

In the Bismarck Reich constitution there was no explicit listing of the basic rights of the citizens, in the sense of a catalog of fundamental rights as in the Frankfurt Reich constitution or numerous other constitutions. The difference between 1848 and 1867 was that in 1849 it was still about the fact that there should be basic rights at all. In 1867 the development in the individual states was so far that one only had to discuss at the federal level whether fundamental rights should also be included in the joint federal constitution. The majority in the Reichstag did not consider this necessary. Rather, it was feared that it would take several months (as in 1848/49) for a fundamental rights debate. Instead, the Reichstag wanted to implement the nation state quickly.

Still, there were a minimum of rights in the state constitution:

- The common indigenous community (Art. 3 Para. 1 and 2 RV 1871) stipulated that a citizen of a single state was also allowed to settle in another and was to be treated there as a resident.

- The state as a whole had to give its citizens diplomatic protection abroad (Article 3, Paragraph 6).

- If a single state denied a citizen the protection of the judiciary, the Federal Council could possibly complain and intervene (Art. 77).

Apart from that, basic rights were realized in the years to come through simple imperial legislation. An important example is the reform of the association system through the law of 1908.

In Prussian legal thought, Carl Gottlieb Svarez established the tradition that lasting principles about right and wrong take the place of individual basic rights and could replace them. These ongoing principles include the prohibition of retroactive effects or the requirement to apply laws regardless of class, rank and gender.

Constitutional Practice

Foreign policy

While the empire's responsibilities in domestic affairs were clearly defined and limited, the empire had broad responsibilities in foreign policy . Foreign policy was basically the responsibility of the Kaiser, who could act amicably with the Chancellor. Declarations of war required the approval of the Federal Council. There was no basic rule according to which the consent of the Federal Council and the Reichstag had to be obtained for contracts and declarations on foreign affairs, defense and protection of the civilian population. Only treaties under international law and declarations on individually designated subjects of Reich legislation were subject to approval. In the field of alliance policy and general foreign policy, the emperor and the imperial chancellor had great scope for shaping. However, the Reichstag was able to limit or refuse the necessary budgetary resources. The states could relate to foreign states in areas in which they had their own jurisdiction.

Relationship between Prussia and the Reich

The constitutional position of Prussia in the German Empire was very dominant:

- The King of Prussia was German Emperor.

- The Chancellor was almost always appointed Prussian Prime Minister. He also became chairman of the Federal Council.

- Even though Prussia had significantly fewer Federal Council votes than the number of inhabitants it had, the votes were sufficient to prevent any constitutional amendment.

- The Prussian War Ministry performed the tasks of a Reich War Office.

Nevertheless, the empire did not become part of Prussia, but Prussia in the empire. In 1909, like the other federal states, Prussia refused to introduce a tax reform to finance the construction of the navy for the Reichsmarine. It was not a new Prime Minister who was appointed Reich Chancellor, but, conversely, a new Reich Chancellor became Prime Minister. It was similar with many other members of the government, who often enough did not come from Prussia. From the Prussian point of view, the empire was thus not a tool for expanding its power to the entire federal territory.

The interaction between the Kingdom of Prussia and the Reich was disturbed by the fact that there were different majorities in the Reichstag and the Prussian Landtag, partly because of the different populations, partly because of the Prussian three-class suffrage. In 1917 the Prussian state parliament took positions on submarine warfare and exaggerated war goals, which were rejected by the Reichstag. This led to delays and half measures. The problem of the oversize of Prussia was not solved in the Weimar Republic either.

Military affairs

The organization of the land army was standardized within the North German Confederation and based on alliance agreements with the southern German states based on the Prussian model even before 1871. The transition process from the North German Confederation to the German Reich was also designed with military conventions under international law. The aim of the constitution was a unified army under the command of the emperor. To this end, the entire Prussian military legislation had to be introduced at short notice throughout the German Empire. Otherwise the Reich had the right to compete legislation in the military sector. In 1874 the comprehensive Reich Military Law of May 2, 1874 was created, which contained organizational regulations, status regulations for soldiers, military substitutes and army reserves.

For a formal declaration of war, the emperor only needed the approval of the Bundesrat, which was chaired by the Chancellor, but not the Reichstag. After that, he was entitled to command and command alone, even without the consent of the Reich Chancellor. The use of the army and navy outside the federal territory did not require the approval of the Reichstag. A Reich War Office as the highest Reich authority headed by a State Secretary, for which the Reich Chancellor would have been responsible, was dispensed with. Instead, the administrative tasks were taken over by the Prussian War Ministry. In order for the ministry to appear before the Bundesrat and the Reichstag, the Minister of War was appointed as the Prussian Federal Council Plenipotentiary, which meant that he had to be heard by the Reichstag at any time.

Not mentioned in the constitution was the Great General Staff, a department of the Prussian War Ministry. In 1883, his boss, Helmuth von Moltke, was given the right to speak directly to the emperor, which the Prussian prime minister could not restrict.

The states retained their troops and some of their previous duties and rights. The troops were merely subordinate to the emperor and subject to his supervision. As chiefs of administration, the states were responsible for the completeness and military efficiency of their troops. They could also appoint the officers of their contingent, with the exception of the highest commanding officers. They could only appoint generals with the consent of the emperor. Individual states managed to reserve further rights in special military conventions. Württemberg thus retained the independent administration of its troops and retained the previous organization and composition. Württemberg appointed the highest commanding officer of the army corps himself with the consent of the emperor. The Württemberg and Prussian war ministries corresponded directly, which made the Württemberg war ministry the intermediate authority of the Prussian war ministry, which also performed the tasks of a supreme Reich authority.

The navy did not consist of contingents from the federal states, but was an organ of the empire. It was under the command of the emperor. The empire had the right to compete naval legislation. In 1889 the High Command of the Navy and the Reichsmarineamt were formed as the highest Reich authority. In the Reichsmarineamt the administrative and procurement matters that belonged to the business circle of the Reich Chancellor were processed. The Naval Cabinet was also founded in 1889. It was the office organization for the Emperor's orders in the command of the Navy. In addition, personnel matters were processed and matters outside the business sphere of the Reich Chancellor and the Naval Office.

Financial constitution of the empire

The member states had to maintain and finance the largest administrations and institutions such as the police, road construction, and universities.

At first the empire had to support the army. The army was unitary and under the command of the emperor. However, it still consisted of the contingents of the individual federal states that were already in place when the empire was founded. The army was initially financed by the Reich; The federal states had to compensate the empire for these expenses. The assessment basis was the army's strength of peace with 1% of the population. 225 Taler or later 675 Marks were to be paid to the Reich for each head of the peacekeeping force . The resulting total amount was allocated to the individual federal members according to the number of inhabitants.

The expenses for civil administration were to be covered by the net income from customs and excise duties, which were due to the Reich Treasury, and the income from the post and telegraph system. If this income was not enough, new imperial taxes should be introduced, or the expenses should be covered by allocations to the individual states. This form of pay-as-you-go financing was described with the catchphrase that the realm was the boarder of the states.

Initially, the costs of the navy had to be met from the Reich treasury. However, these costs could be passed back to the states if the empire's own income was insufficient. However, these matriculation fees were so substantial that they would have been felt by the states. That is why the cost of building the navy was financed through loans. The imperial debt amounted to 1.1 billion marks in 1890, 2.1 billion marks in 1895 and rose to 4.8 billion marks by 1912. In 1908 attempts were made to make borrowing superfluous and to increase taxes. There was no majority in the Reichstag for this financial reform.

The financing of the war from 1914 onwards remained on the levy structure and was primarily carried out through borrowing from the Reich rather than through increased taxation. This laid the foundation for inflation from 1918 onwards.

Reasons for the failure of the Reich and the Constitution

The emperor's power of command was too broad and unlimited in time. Bismarck himself was only able to assert himself as Prussian Prime Minister in 1866 in the German-Austrian War against the King of Prussia and the military by threatening to resign. Nevertheless, he made no restriction on the excessive power of command. The Chancellor played too little of a role in the conduct of the war. The Emperor and the Supreme Army Command neglected the foreign and geopolitical aspects of military action. In January 1917, after hearing the Supreme Army Command, the three imperial cabinets and the Reich Chancellor, the emperor ordered unrestricted submarine warfare. This decision led to the entry of the United States into the First World War in April 1917. The fact that the Kaiser transferred his authority to issue orders to the highest command authorities of the field army to the General Staff in August 1914 led to a centralized bureaucracy at the expense of the Reich leadership and the federal states, which was tantamount to a military government.

The Reichstag could not end the use of the army and navy of its own accord, because only the emperor was the holder of command and control. The responsibility of the Reich Chancellor to the Reichstag was too weak. The Reichstag was also unable to indirectly enforce its political will towards the Emperor, Supreme Army Command and Imperial Chancellor. The control of the government was excluded from the balance of power between the parliament and the government. Because of this, the Emperor and the Supreme Army Command could develop a preponderance which the Reich Chancellor could not counter with the powers of the Reichstag. Members of the Reichstag could not hold the office of State Secretary, so that the Reich leadership could not accept any personalities with political support and expertise acquired in the Reichstag. It therefore lacked members with a geopolitical understanding. The disadvantaged position of Alsace-Lorraine in the constitution is no longer seen as an incentive to recapture, because the great majority of Alsatians and Lorraine people no longer strived for reunification with France since 1890, but for complete equality in the German Empire.

See also

- Paul's Church Constitution (Frankfurt Reich Constitution)

- Erfurt Union Constitution

literature

- The minutes of the Prussian State Ministry 1817–1934 / 38. Volume 10, edited by R. Zilch. Hildesheim, Zurich / New York 1999.

- Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg : reflections on world wars. Edited by Jobst Dülffer, Essen 1989.

- Otto von Bismarck : Thoughts and Memories. New edition, Stuttgart / Berlin 1928.

- Jost Dülffer : Germany as an empire. In: Martin Vogt (Hrsg.): German history from the beginnings to the present. 3rd edition, Frankfurt am Main 2006, pp. 517–615.

- Bernt Engelmann : Prussia, land of unlimited possibilities. Munich 1980.

- Fritz Fischer : Reach for world power. The war target policy of imperial Germany 1914/1918 . Reprint (2004) of the special edition 1967, Düsseldorf 1961, 1967, 1977.

- Sebastian Haffner : From Bismarck to Hitler. Reprint, Munich 2015.

- Ernst Rudolf Huber : German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the empire. 3rd edition, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988.

- Henry Kissinger : Diplomacy. New York [u. a.] 1994.

- Paul Laband : The constitutional law of the German Empire. Volume 1, Tübingen 1876.

- Adolf Laufs : Legal developments in Germany. 6th, revised and expanded edition. De Gruyter Law, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-89949-301-X .

- Wolfgang J. Mommsen : Was the emperor to blame for everything? Wilhelm II and the Prussian-German power elites. Berlin 2005.

- Gustav Seeber : The German Empire from its founding to the First World War 1871–1917. In: Joachim Herrmann et al. (Ed.): German history in ten chapters. Berlin 1988, pp. 247-297.

- Volker Ullrich : The nervous great power 1871-1918. The rise and fall of the German Empire. Extended new edition, Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2013.

- Heinrich August Winkler : History of the West. From the beginnings in antiquity to the 20th century. Munich 2009, paperback edition 2013.

- Manfred Zeidler : The German war financing 1914. In: Wolfgang Michalka (Hrsg.): The first world war, causes - effects - consequences. Weyarn 1997, pp. 416-433.

Web links

- Law on the Constitution of the German Reich (Reich Constitution of April 16, 1871) in full text

- Federal treaty with Baden and Hesse (including the constitution of the German Confederation) of November 15, 1870

- Federal treaty on the accession of Bavaria to the constitution of the German Confederation of November 23, 1870

- Treaty between the North German Confederation, Baden and Hesse on the one hand, and Württemberg on the other, regarding the accession of Württemberg to the constitution of the German Confederation (including the military convention) of November 25, 1870

- Constitution of the German Confederation - as agreed in accordance with the protocol of November 15, 1870 between the North German Confederation, Baden and Hesse; with the changes made by the treaties of November 23 and 25, 1870 with Bavaria and Württemberg

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Michael Kotulla : German Constitutional Law 1806-1918. A collection of documents and introductions. Volume 1: Germany as a whole, Anhalt states and Baden. Springer, Berlin [a. a.] 2006, ISBN 3-540-26013-7 , Part 1, § 7, pp. 247-249 ; see Daniel-Erasmus Khan : The German State Borders. Legal historical foundations and open legal questions (= Jus Publicum. Vol. 114). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2004, ISBN 3-16-148403-7 , p. 55, fn 4 (also Univ. Habil.-Schr., Munich 2002/2003).

- ↑ Art. 15 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber : German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich , 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 735.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich , 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 736.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich , 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 737.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich , 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 750.

- ↑ RGBl. 1871, p. 63 ff.

- ↑ Werner Frotscher , Bodo Pieroth : Verfassungsgeschichte. 5th, revised edition, Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-53411-2 , Rn. 383; see also the list of the “November contracts” from 1870 by Daniel-Erasmus Khan: The German State Borders. Legal historical foundations and open legal questions , Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2004, p. 55, fn 3.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich , 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 759.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich , 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 750.

- ^ Daniel-Erasmus Khan, Die deutscher Staatsgrenzen , 2004, p. 55 .

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich , 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 649.

- ↑ Sebastian Haffner : Von Bismarck zu Hitler , Munich 2015, p. 139.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich , 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 788 f.

- ↑ Art. 17 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 3 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 30 and 83 GG.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich , 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 759.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich , 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 760.

- ↑ Art. 78 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 69 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 73 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 62 sentence 3 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 62 sentence 4 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 35 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 68 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 4 Nos. 1, 2, 3 and 8 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 78 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich , 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 795.

- ↑ Art. 4 Clause 1 No. 13 RV 1871 as amended.

- ↑ Art. 4 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 17 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 36 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 7 Clause 1 No. 3 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 19 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 50 sentence 6 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 52 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 42 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 46 sentences 2 and 3 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 7 No. 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 37 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 36 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 43 sentences 1 and 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 74 and 75 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 4 No. 13 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 76 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 76 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich , 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 791.

- ^ Rudolf Hoke : Austrian and German legal history. 2nd, improved edition, Böhlau, Vienna [u. a.] 1996, ISBN 3-205-98179-0 , p. 421 .

- ↑ Art. 6 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 15 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 5 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 7 No. 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 7 No. 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 4 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 6 No. 3 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 76 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 8 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 6 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 6 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 7 sentence 4 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 29 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 7 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 29 RV 1871.

- ^ Paul Laband: Das Staatsrecht des Deutschen Reiches , Volume 1 Tübingen 1876, p. 321 f.

- ↑ Art. 5 sentence 3 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 7 sentence 4 i. In conjunction with Art. 35 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 3 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 7 sentence 3 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. I of the Alsace-Lorraine Constitution of May 31, 1911.

- ↑ Art. II, § 2 Clause 4 Law on the Constitution of Alsace-Lorraine of May 31, 1911.

- ↑ Art. I Clause 3 of the Act on the Alsace-Lorraine Constitution of May 31, 1911.

- ↑ Art. II § 1 Law on the Constitution of Alsace-Lorraine of May 31, 1911.

- ↑ Art. 11 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich. 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 810.

- ^ Constitutional charter for the Prussian state of January 31, 1850 , verfassungen.de, accessed on June 24, 2017.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich. 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 815.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich. 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 810.

- ↑ Art. 17 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich. 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 1003.

- ↑ Art. 11 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 11 sentence 3 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 17 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 4 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 11 sentence 4 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 11 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 17 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 5 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 24 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 15 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 17 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 19 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 17 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Wolfgang J. Mommsen: Was the emperor to blame for everything? Wilhelm II and the Prussian-German power elites , Berlin 2005, p. 142 f.

- ↑ Art. 18 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 56 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 50 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 63 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 11 sentence 3 RV 1871.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich , 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 1003.

- ↑ Art. 64 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 63 sentence 6 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 63 sentence 7 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 60 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 62 sentence 4 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 53 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 53 sentence 3 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 69 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 68 RV 1871.

- ↑ Section 4 of the State of Siege Act of June 4, 1851.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich. 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 1045.

- ↑ § 3 sentence 1 of the law on the union of Alsace and Lorraine with the German Empire of June 9, 1871.

- ↑ § 4 of the law on the union of Alsace and Lorraine with the German Empire of June 9, 1871.

- ↑ § 3 Clause 4 of the Act on the unification of Alsace and Lorraine with the German Empire of June 9, 1871.

- ↑ Art. 15 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 18 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 63 sentence 1, Art. 53 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Quotation from Stefan Malorny: Executive veto rights in the German constitutional system. A systematic presentation and critical appraisal with special consideration of the legal historical development as well as the institutional fitting into the parliamentary democratic structures of Germany and Europe (= Göttinger Schriften zum Demokratie, Vol. 2). Universitäts-Verlag, Göttingen 2011 (also: Göttingen, Univ., Diss., 2010), ISBN 978-3-86395-002-6 , p. 2 .

- ↑ Volker Ullrich: The nervous great power 1871-1918. Rise and fall of the German Empire , Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2013, p. 152 f.

- ↑ Art. 11 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ No. 1 Law amending the Reich Constitution of October 28, 1918.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich , 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 823.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich , 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, pp. 816–819.

- ^ The protocols of the Prussian State Ministry 1817–1934 / 38. Volume 10, edited by R. Zilch. Hildesheim / Zurich New York 1999, introduction, p. 23.

- ↑ Fritz Fischer: Reach for world power. The war target policy of imperial Germany 1914/1918 . Reprint (2004) of the special edition 1967, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 319.

- ↑ Art. 5 para. 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 4 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 23 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 69 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 53 sentence 4 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 60 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 62 sentences 1 and 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 62 sentence 5 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 69 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 29 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 32 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 21 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 31 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 22 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 20 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 24 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 24 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 17 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ^ Klaus Erich Pollmann: Parliamentarism in the North German Confederation 1867-1870 , Droste, Düsseldorf 1985, pp. 207/208.

- ↑ Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional Law 1806-1918. A collection of documents and introductions. Volume 1: Germany as a whole, Anhalt states and Baden , Springer, Berlin [a. a.] 2006, p. 254.

- ^ Adolf Laufs: Legal developments in Germany. 6th edition, Berlin 2006, p. 186.

- ↑ General Land Law for the Prussian States of June 1, 1794, Introduction, § 14.

- ↑ General Land Law for the Prussian States of June 1, 1794, Introduction, § 22.

- ↑ Art. 11 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 17 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 11 sentence 3 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 11 sentence 4 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 69 RV 1871.

- ↑ Bernt Engelmann: Prussia Land of Unlimited Possibilities , Munich 1980, p. 343.

- ↑ Volker Ullrich: The nervous great power 1871-1918. Rise and Fall of the German Empire , Frankfurt am Main 2013, p. 220.

- ^ Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg: Reflections on World Wars , edited by Jost Dülffer, Essen 1989, p. 236 f.

- ↑ a b c Gustav Seeber: The German Empire from its foundation to the First World War 1871–1917. In: Joachim Herrmann (Ed.): German history in ten chapters. Berlin 1988, pp. 247-297, here p. 252.

- ↑ Art. 63 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 61 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 4 No. 14 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 11 sentence 3 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 17 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 63 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 9 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 63 sentence 5 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 66 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 64 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 64 sentence 4 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 12 sentence 1 Military Convention between the North German Confederation and Württemberg of 21./25. November 1870.

- ↑ Art. 5 sentence 1 Military Convention between the North German Confederation and Württemberg of 21./25. November 1870.

- ↑ Art. 15 sentence 1 Military Convention between the North German Confederation and Württemberg of 21./25. November 1870.

- ↑ Art. 53 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 4 No. 14 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 63 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 63 Clause 4, Art. 66 Clause 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 62 sentence 4 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 62 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 62 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 60 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 70 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 38 sentence 1 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 49 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 70 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 70 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Jost Dülffer: Germany as an empire. In: Martin Vogt (Hrsg.): German history from the beginnings to the present. 3rd edition, Frankfurt am Main 2006, pp. 517-615, here pp. 590 f.

- ↑ Art. 53 sentence 4 RV 1871.

- ↑ Art. 70 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ↑ Jost Dülffer: Germany as an empire. In: Martin Vogt (Hrsg.): German history from the beginnings to the present. 3. Edition. Frankfurt am Main 2006, pp. 517–615, here p. 538.

- ↑ Art. 73 RV 1871.

- ↑ Jost Dülffer: Germany as an empire. In: Martin Vogt (Hrsg.): German history from the beginnings to the present. 3rd edition, Frankfurt am Main 2006, pp. 517–615, here p. 538.

- ↑ Manfred Zeidler: The German War Financing 1914. In: Wolfgang Michalka (Hrsg.): The First World War, causes-effects-consequences. Weyarn 1997, pp. 416-433, here pp. 418 f.

- ↑ Otto von Bismarck: Thoughts and Memories. Stuttgart and Berlin, new edition 1928, pp. 370–374.

- ↑ Volker Ullrich: The nervous great power 1871-1918. Rise and fall of the German Empire , Frankfurt am Main 2013, p. 512 f.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich. 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 777.

- ↑ Art. 21 sentence 2 RV 1871.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789 , Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich. 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1988, p. 830.

- ^ Henry Kissinger : Diplomacy. New York 1994, p. 179.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler : History of the West. From the beginnings in antiquity to the 20th century. Munich 2009, paperback 2013, p. 1093.