Basic rights of the German people

The basic rights of the German people are a basic rights catalog from the year 1848. First it was put into effect by Reich legislation on December 27, 1848, as the Reich law concerning the basic rights of the German people (Frankfurter Grundrechtsgesetz, GRG). In 1849 the Frankfurt constitution repeated the basic rights almost unchanged. Although the law had been promulgated in accordance with current Reich legislation, the larger German states rejected it. In 1851 the Bundestag expressly declared the Frankfurt fundamental rights to be invalid.

If applied, the Frankfurt catalog of fundamental rights would have made a decisive contribution to the freedom of Germans, the rule of law and the unification of Germany . It contains hardly any social rights, but goes far beyond the classic freedom rights . For example, it was also stipulated that the individual states had to have elected representative bodies and ministerial responsibility. The fundamental rights were hardly disputed in the National Assembly and were seen by the MPs as a priority in order to secure the freedom achieved so far in the revolution .

history

Basic rights in the pre-march

Although fundamental rights had already been discussed when the German Confederation was founded, the Federal Act of 1815 contained only a few provisions in this regard in Articles 18 and 19. Accordingly, the three main Christian denominations were not allowed to be discriminated against each other, one was free to acquire real estate or to move from one German country to another and could enter into civil or military service in another country. The freedom of the press remained a mere promise. In contrast, the constitutional monarchies of southern Germany and, after the July Revolution of 1830 , other states, included catalogs of fundamental rights in their constitutions .

Law and Imperial Constitution 1848/1849

In 1848 basic rights were central demands of the revolutionary movement ( March demands ); the Bundestag's seventeen draft already provided for guarantees of fundamental rights. In the pre-parliament (March / April) one spoke of rights, a “declaration of rights of the German people”, principles and foundations. The expression "basic rights" in this context comes from Jacob Venedey , the compromise formula was: "Basic rights and demands of the German people". In the National Assembly, terms such as “original rights” (with a natural law background), “civil rights” or “people's rights” appeared.

The Frankfurt National Assembly regarded the question of fundamental rights as having priority over decisions on future imperial power, because it wanted to bind the state authority of the individual states. The fundamental rights stood not only for freedom, but also for national unity, because the same foundations for the legal culture should apply everywhere. However, according to Ernst Rudolf Huber , valuable months passed in which the individual states, especially Austria and Prussia , regained power. "In an effort to secure freedom before unity was won, the Frankfurt National Assembly gave up freedom and unity at the same time." Wolfram Siemann, however, considers the procedure to be justified because the March demands had already demanded the safeguarding of civil rights, Because the members of parliament had previously had experience with the police state, because the central authority that was soon to be established anticipated state unity and opened up scope for basic rights, and because in May 1848 it was not yet to be expected that the old forces would regain strength so quickly.

The Constitutional Committee was very unanimous about fundamental rights; they should “set the limit” for the great social movement that has gripped all of Germany. On May 26, the constitutional committee decided to set up a subcommittee for fundamental rights, with the MPs Friedrich Dahlmann , Robert von Mohl and Eugen von Mühlfeld . They submitted a first draft on June 1, which was submitted to the plenary session of the National Assembly on June 19.

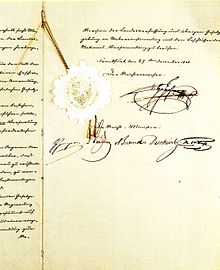

The plenum discussed it for more than half a year, with the most controversial provisions affecting the economic and social constitution or church and school issues. Finally, the National Assembly passed the basic rights on December 20, 1848. The Deputy Adolph Schoder applied for immediate implementation as a Reich law, which was followed by the National Assembly on December 21. The Reichsverweser , the provisional head of state, drafted the law on December 27th. The fundamental rights should be immediately binding.

The imperial constitution provided for a imperial court that every German could appeal if the empire or a member state violated their constitutional rights, especially basic rights. A law was supposed to regulate such a complaint, a Reich constitutional complaint , more precisely, but that never happened. Such personal legal protection was only realized in Germany in 1951 with the Federal Constitutional Court .

Validity and abolition

The Basic Rights Act provided that the administration , the judiciary and also the legislature were bound by the basic rights . Conversely, neither imperial laws nor state laws could limit basic rights. Certain legal reservations in the Basic Rights Act itself were an exception , namely with regard to freedom of movement, freedom of trade, freedom of housing, confidentiality of letters, freedom of the press, freedom of worship and the self-administration of religious societies. With regard to expropriations , the property guarantee could be limited, and there were a few other cases. However, the most important fundamental rights did not have such reservations. However, it was unclear whether, in the event of a state of emergency (§ 54, 55 FRV), basic rights could be overridden in order to safeguard the Reich peace.

The basic rights had to be specified in a simple law. The Introductory Act provided for their immediate application or, if this was not possible, that they should be implemented as soon as possible (in relation to the independence of religious communities) or within six months (in relation to the abolition of professional privileges in state constitutions).

According to the Reich law on the promulgation of the Reich laws and the orders of the provisional central authority of September 27, 1848, Reich laws came into force when they were promulgated in the Reichsgesetzblatt . It was therefore not necessary that they were also published in the relevant organs of the individual states. The Central Authority Act of June 28th gave the Reich Administrator the right to have laws come into force; the Reichsverweser had also been expressly recognized by the individual states .

Most states published or recognized the constitutional law. The larger ones, on the other hand, such as Austria, Prussia, Bavaria , Hanover and others, rejected it and did not publish it either. From a legal point of view, this was irrelevant for the validity of the Reich Law, but in reality the basic rights could not be enforced against the will of a state. After the crackdown on the revolution in 1849 and the restoration of the German Confederation in 1851, the Bundestag declared the fundamental rights invalid by a separate resolution of 23 August 1851. If countries had changed their own law accordingly due to the Reich Law, this had to be reversed.

Fundamental rights

The concept of fundamental rights at that time was broader than that in Vormärz or in the reaction time and did not only encompass the classic freedom rights. Georg Beseler from the Constitutional Committee saw the fundamental rights in the light of the cooperative approach : The fundamental rights were all rights of individual members of the state and of non-state organizations. In contrast, there was only the organization of the state as a whole. That is why the basic rights deal with, for example, the individual states (§§ 130 S. 2, 186 f. FRV) as well as the private religious societies (§ 147 FRV), which, like associations, are called cooperatives. The basic rights regulate the "entire, considered necessary substructure of the Reichsgenossenschaft", so Kühne.

Fundamental rights should take into account both individual freedom and the general interest; they are to be seen both as defensive and state-building. They had these main functions:

- Uniform function: the rights of Germans should be standardized

- Rule of law function: the rule of law should be established in Germany

- Modernization function: obsolete privileges and forms of organization should be abolished or redesigned

Freedom of person and freedom of spirit

The catalog of basic rights begins with citizenship of the Reich for all Germans (citizens of the individual states). A citizen of the Reich enjoyed freedom of movement , he was allowed to emigrate and practice a trade of his choice. The freedom of trade was a point of contention in the National Assembly, but a separate all-German trade regulation remained only a draft law.

The Germans were to be right before the law, class differences and privileges were abolished; this abolition of the nobility naturally aroused opposition to fundamental rights. Titles were abolished unless they were official titles . Access to public office was open to all qualified people. The military should be the same without the possibility can be replaced by an alternate. Tax equality was guaranteed.

In order to safeguard the freedom of the person, arrests were only permitted if a judicial arrest warrant was available. With some exceptions, the death penalty was abolished, and punishments such as pillory , branding and corporal punishment were abolished. The basic rights guaranteed freedom of residence, the secrecy of letters, and abroad a Reich citizen enjoyed the consular protection of the Reich.

Spiritual and religious freedom

The catalog of fundamental rights also wanted to ensure full freedom in the area of the spirit and public opinion , through freedom of the press including the abolition of censorship and freedom from academic research and teaching . The Germans should have the right to petition , freedom of assembly and freedom of association . Meetings in the open air could only be banned if there was an imminent threat to public safety and order .

Full freedom of conscience and belief ensured the practice of religion at home and in public. The churches were allowed to organize themselves, differences in state church law between the main Christian denominations and other communities were abolished; the disadvantage for the main denominations was the loss of privileges, and there were no more state churches . The membership of a particular religion no longer affected the rights of citizenship, and was allowed to have a church wedding is only after civil marriage ceremony. This was a radical lesson from the previous mixed marriage conflict .

The schools would henceforth only by the state, are no longer supervised by the churches. The state also had to provide for the establishment of state schools with teachers in the position of public servants. However, private schools were allowed to be founded, which was particularly beneficial for Catholics. Elementary schools could be attended without paying school fees. Everyone had the freedom to choose their profession and the training opportunities.

Freedom of property and basic social rights

The property was inviolable, intervention in this property freedom were possible only within narrow limits. Expropriations could only take place if they served the “common good”, were based on law and if there was fair compensation. "These Frankfurt expropriation rules have held their own up to the present day," said Huber. Some property ties were abolished: a landowner was free to sell and share the land. Feudal rights such as bondage and patrimonial jurisdiction and manorial police were also abolished. Deprivation of property could no longer be used as a punishment.

Left MPs called for a right to work ; after the subject was only touched on in the Constitutional Committee, it came up again in the plenary session of the National Assembly. The proponents wanted to see the law realized by ensuring that the involuntarily unemployed did not receive their full maintenance. Instead, they either should live minimum assurance or assigned work. The working classes should be integrated into the state and thus kept from violence.

The liberal majority in the National Assembly, on the other hand, was of the opinion that freedom of trade and competition was sufficient to enable the able-bodied from the lower classes to move up in society. That is why the right to work and other basic social rights are missing in the Basic Law, with the exception of the exemption from school fees for the poor (Section 27 (2) GRG = Section 157 FRV), says Huber.

Kühne, on the other hand, sees more social echoes. The equality clauses for the abolition of the privileges of the nobility "aim to a large extent in 1848/1849 to reorganize the political and social constitution". The imperial constitution would have divided into the people and into the privileged regent families (around 130 noblemen), while in fact after 1850 around 1% of the population remained privileged and, for example, through the first chambers, impaired constitutional life and inhibited development.

Institutional guarantees

Certain state institutions were also protected by the catalog of fundamental rights. The administration of justice should be independent, exceptional courts should be prohibited and all judicial power should emanate from the state. Only a judicial verdict could remove a judge from office. Usually, court hearings had to be public and verbal. Civil courts , not the administration, should deal with violations of public law .

The congregations were allowed to administer themselves , above all to elect their heads and councils themselves; however, state supervision set legal limits. The catalog of fundamental rights prescribed a constitution for the individual states with representation of the people and ministerial responsibility . The representatives of the people had to be able to take part in decisions, among other things, about state laws, taxation and the determination of the budget. As a rule, your meetings should be public.

A special feature among the institutional guarantees was the Frankfurt minority protection :

- § 188. The non-German speaking tribes of Germany are guaranteed their popular development, namely the equality of their languages, as far as their areas extend, in church affairs, teaching, internal administration and the administration of justice.

Austrians had applied for this minority protection, which was intended for the situation in ethnic mixes. The "specific Austrian ingredient for FRV" was then in Austria the "prelude to the probably most significant contribution" of the country for the development of constitutional law in the 19th century given, Kuehne. It is still praised today as a humane solution.

The enumeration of ecclesiastical affairs etc. was only exemplary and not conclusive. By equality it was meant that the minority language should be on an equal footing with German in the area concerned , not that only the minority language was valid there. If the majority of the residents in a district had a minority language behind them, they should be "left their language". Otherwise the individual state could freely organize the protection of minorities.

In the National Assembly it was mostly discussed in relation to Austrian cases, only rarely in relation to the Danes and Slavs in northern Germany. That is why it received little attention later in small Germany and was deleted from the Erfurt Union constitution , as it only affects Prussia and perhaps Saxony . This can be dealt with in the rules of the individual states. Resistance came not so much from the governments there, but from the liberal parliamentary groups.

outlook

The Frankfurt fundamental rights remained a point of reference in German constitutional history for a long time. In the draft of his Federal Constitution of 1866/1867, Bismarck at least adopted some important fundamental rights that the state as a whole or the simple legislature should be allowed to regulate. Express fundamental rights were essentially missing, only in a draft by the forty-eighter Oskar von Reichenbach of the Democrats they still appeared, where they were strongly based on the imperial constitution. Former members of the Frankfurt National Assembly were of the opinion in the North German Reichstag that the attempted establishment of the state of 1849 had also failed because of the deliberations on fundamental rights. As a result of Württemberg's insistence on the November treaties, freedom of the press, freedom of association and freedom of assembly were at least partially incorporated into the constitution in 1870.

In the Weimar National Assembly in 1919, Hugo Preuss , on whom the draft constitution at that time was based, said that basic rights had already been realized in the simple legislation of the member states. A large part of the fundamental rights have lost their practical importance. Contrary to his original intention, at the request of the Council of People's Representatives , he nevertheless spoke out in favor of basic rights in the imperial constitution so that - apart from the guarantee provided by the constitution - simple imperial laws could also provide guidelines for the member states. The “Sub-Committee for the Preliminary Consultation on Fundamental Rights” made tangible use of the Frankfurt Fundamental Rights. It stayed that way in the plenary debates, but there were also basic social rights.

MEPs still feared that long debates on fundamental rights would lose time. In contrast to 1848/1849, little attention was paid to the questions of how fundamental rights could be enforced and protected by a constitutional court. Rather, the MPs were concerned about whether the Weimar catalog of fundamental rights was consistent with the existing laws. The SPD and the center in particular campaigned for the inclusion of fundamental rights , while the liberals held them in low regard.

rating

According to Jörg-Detlef Kühne , the Frankfurt basic rights did not simply mean a connection to Western constitutional systems, they went their own, specifically German paths and even clearly exceeded this Western standard. The individual basic rights developed the legal conditions found only moderately, but taken together their potential for change was truly revolutionary. Her inhibition of power in Germany was not achieved until 1918.

He also considers them practicable: "In contrast to the fear of the governments of that time, you could definitely rule with them." Because of numerous regulatory reservations, he is amazed at the great confidence in the legislature, which stemmed from the fact that the revolutionaries still very much from the unity of People and representatives went out. In the Weimar Republic, such reservations later led to an “extensive emptying of fundamental rights”, which is why the Bonn Basic Law outlined the reservations sharply instead.

According to Dietmar Willoweit , the Frankfurt Fundamental Rights were the first attempt “to codify fundamental rights as directly applicable law and to protect them through constitutional complaints before a state court.” According to Judith Hilker, the Frankfurt Fundamental Rights would have evolved into a democratic nation-state and an alignment with human rights declarations of North America and France can enable. However, this was already prepared by the basic rights of early constitutionalism in Vormärz. You had just challenged the people to “work towards the actual implementation of the program”.

The legal historian Hans Hattenhauer judged the Frankfurt catalog of fundamental rights:

“ Philosophical demands had become legal clauses that every citizen could invoke to be binding. Any future legal order that wanted to bypass the rights of the citizen had to expressly or tacitly remove this catalog of fundamental rights [...]. This first German catalog of basic rights should be required reading for every educated German. What distinguished him was the legal clarification of the philosophical demands of the Enlightenment. Nothing was vague or general. Everything was tailored to the needs of the time. "

See also

literature

- Jörg-Detlef Kühne : From the bourgeois revolution to the First World War . In: Detlef Merten, Hans-Jürgen Papier (ed.): Handbook of fundamental rights in Germany and Europe . Volume I: Developments and Basics . CF Müller Verlag, Heidelberg 2004, pp. 97–152.

- Heinrich Scholler (ed.): The fundamental rights discussion in the Paulskirche. A documentation. 2nd edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1982.

supporting documents

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber : German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 774.

- ^ Jörg-Detlev Kühne: From the bourgeois revolution to the First World War . In: Detlef Merten , Hans-Jürgen Papier (ed.): Handbook of fundamental rights in Germany and Europe . Volume I: Developments and Basics . CF Müller, Heidelberg 2004, pp. 97-152, RN 3, 8, 9.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 774/775, p. 782.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann : The German Revolution of 1848/49. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1985, p. 136.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), p. 161.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 775.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 775/776.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 835.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 781/782.

- ^ Judith Hilker: Basic rights in German early constitutionalism . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, pp. 291-293.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 782/783.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 783.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), p. 163/164, p. 166, p. 171.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), p. 169/170.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), pp. 173/174.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 778.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 778.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 778.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 779.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 780.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 780.

- ^ Heinrich Scholler (ed.): The discussion of fundamental rights in the Paulskirche. A documentation. 2nd edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1982, pp. 44/45.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 777.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), p. 163, 327/328.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 780/781.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 781.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), p. 309/310.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), p. 309/310.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), p. 310.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), pp. 114/115.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), pp. 136-139.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), pp. 139–141.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), pp. 380/381, 526.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), pp. 516/517.

- ↑ Dietmar Willoweit : German constitutional history. From the Franconian Empire to the reunification of Germany . 5th edition, CH Beck, Munich 2005, p. 304.

- ^ Judith Hilker: Basic rights in German early constitutionalism . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, p. 362.

- ↑ Hans Hattenhauer : The historical foundations of German law . 3rd edition, CF Müller Juristischer Verlag, Heidelberg 1983, p. 131 (RN 273, 275). Emphasis in the original.