Weimar National Assembly

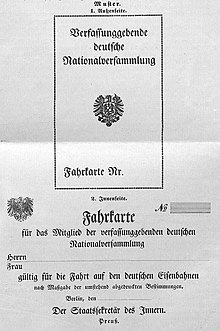

The Weimar National Assembly , officially the constituent German National Assembly , was the constituent parliament of the Weimar Republic . It met from February 6, 1919 to May 21, 1920. The venue until September 1919 was Weimar , not the politically heated capital of Berlin . The chairmanship of the first meeting on February 6, 1919 was chaired by Wilhelm Pfannkuch (SPD) as senior president. The list of members of the National Assembly from 1919 gives an overview of all members of the assembly .

prehistory

In the course of the November Revolution of 1918, both the Reich Chancellor Prince Max von Baden , who announced the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II , and the ranks of the majority Social Democrats called for a national assembly to be set up as quickly as possible to determine the future form of government of the German Reich should decide. The Council of People's Representatives , the Provisional Government, decided this on November 30, 1918 and set the election for January 19, 1919. According to the ordinance, all German men and women who had reached the age of 20 on election day were entitled to vote , which was the first time women nationwide had the right to vote . The Reich Congress of Workers 'and Soldiers' Councils ( Reichsrätekongress ) also approved this government resolution with a clear majority on December 19, which finally stopped a - likewise possible - development towards a soviet republic .

Because of the Spartacus uprising , it was agreed that the National Assembly should not meet in Berlin for the time being. The decision on the location of the conference was prepared by the Reichstag director and a privy councilor by exploring four possible locations in January 1919 - Bayreuth, Nuremberg, the Volkshaus Jena and the Hoftheater Weimar . Before that, several other places had gotten into conversation. Weimar was chosen on January 14, 1919.

President and law on provisional imperial power

After the elections on January 19 , the National Assembly met in Weimar on February 6, 1919 . She elected the SPD politician Eduard David as her president. He entered the government shortly afterwards, so that on February 14, 1919, the National Assembly elected the center deputy and previous vice-president Constantin Fehrenbach as his successor.

On February 11, the law on provisional imperial power passed the day before came into force, and the National Assembly elected the previous head of government Friedrich Ebert ( SPD ) as provisional president . The Scheidemann cabinet he installed was based on the Weimar coalition , with the SPD, the center and the DDP .

Advice on the Versailles Treaty and formation of the Bauer cabinet

Explanation by Scheidemann

On May 12, 1919, the National Assembly met for the first time in Berlin, in the New Aula of the university . There she received a declaration from Prime Minister Philipp Scheidemann on the peace conditions and then debated them. In his speech, Social Democrat Scheidemann called the Entente conditions a “violent peace”, which was supposed to strangle the German people , to great applause from all parties . The territorial, economic and political demands would take Germany's air to life. These conditions are unacceptable and are in stark contrast to the assurances that US President Woodrow Wilson has made. The Reich government could not agree to these conditions and would make counter-proposals based on Wilson's 14-point program . The Prussian Prime Minister Paul Hirsch assured the government of the Reich on behalf of the member states of the German Reich full support and also sharply criticized the conditions of the Entente . The speakers of all parties from the USPD to the DNVP also declared the Entente's demands unacceptable. The DVP chairman and later Reich Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann literally described the peace conditions of the victorious powers as an “outflow of political sadism”. Only the USPD chairman Hugo Haase combined his rejection of the Entente demands with sharp attacks on the Reich government and accused it of having caused the current situation through the truce policy during the war .

Resignation of the Scheidemann cabinet; Education of the government peasant

After the Scheidemann cabinet resigned on June 20, 1919 because of the rejection of its counter-proposals by the Entente and the resulting disagreement over the question of the signing of the Versailles Treaty , the new Prime Minister Gustav Bauer , who headed a government of the SPD and the center, campaigned for the Signing of the contract, but continued to criticize individual provisions, in particular regarding the extradition of Germans to the Entente and the burden of war guilt on Germany alone. However, he combined his call for consent with the remark that it would be impossible for the German Reich to fulfill all the economic conditions of the contract and regretted that it had not been possible to wrest further concessions from the Entente.

General indignation

The speakers from the SPD and the center , Paul Löbe and Adolf Gröber , also condemned the treaty. In particular, they objected to the statement made in the Entente's draft treaty that Germany was solely to blame for the war. However, on behalf of their political groups, they spoke out in favor of acceptance, as the only alternative was to resume fighting, which would lead to even worse results. On the other hand, Eugen Schiffer , the previous Reich Finance Minister, spoke out on behalf of the majority of the DDP MPs against the acceptance of the treaty. He reminded the two ruling parties of the proclamation made by the previous Chancellor Philipp Scheidemann on May 12th that the hand that signed this treaty must wither. He does not see that the situation has changed since then. Also DNVP and DVP objected strenuously against the treaty. The USPD, on the other hand, was the only opposition party to approve the Versailles Treaty . Its chairman Hugo Haase called the question to be decided a terrible dilemma in which the National Assembly found itself. He also criticized the treaty sharply, pointing out - like the representatives of the governing parties - the consequences that would arise if the treaty were rejected.

In a roll-call vote, 237 MPs voted for the signing of the peace treaty, 138 voted no, five abstained. While the SPD (except for Valentin Schäfer ), Zentrum (except for nine members) and USPD approved the Versailles Treaty, DDP (except for seven members), DNVP , DVP , the German-Hanoverian Party and the two members of Brunswick-Lower Saxony rejected it Party ( August Hampe ) or Schleswig-Holstein farmers and farm workers democracy ( Detlef Thomsen ) the contract. The MPs of the Bavarian Farmers' Union and two Bavarian center MPs, Georg Heim and Martin Irl, abstained . While the seven center deputies who voted no came predominantly from areas that were threatened with separation from the German Reich by the peace treaty (such as Bartholomäus Koßmann from Saarland or Thomas Szczeponik from Upper Silesia ), among the seven DDP deputies who The parliamentary group chairman Friedrich von Payer , who was unable to assert himself with his view in his parliamentary group , voted for the signing of the contract by the Reich government . Ludwig Quidde , a well-known pacifist and DDP member of the DDP (1927 Nobel Peace Prize ) , voted against it .

No alternative

After the Reich government had informed the Entente states in a note on the same day that they would sign the treaty subject to the provisions on war guilt and the extradition of Germans to the victorious powers, the French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau replied on the evening of June 22nd that the contract can only be accepted or rejected in its entirety.

At the meeting of the National Assembly on June 23, Prime Minister Bauer informed the plenary session of the Entente's stance and stated that the government no longer had a choice and had to sign the treaty:

"Ladies and gentlemen! No more protest today, no storm of indignation. Let's sign, that is the proposal I have to make to you on behalf of the entire Cabinet. The reasons that compel us to make this proposal are the same as yesterday, except that we are now separated by just under four hours before hostilities can resume. We cannot answer for a new war, even if we had weapons. We are defenseless, but defenseless is not dishonorable. Certainly, the opponents want us to honor, there is no doubt about that, but that this attempt to cut off honor will one day fall back on the authors themselves, that it is not our honor that perishes in this world tragedy, that is my belief, until last breath. "

While Eugen Schiffer (DDP) and Rudolf Heinze (DVP), whose parties had refused to accept the contract the day before, expressly stated in their speeches that the proponents of the contract also act exclusively out of “patriotic sentiments and convictions” (as Schiffer literally said) DNVP speaker Georg Schultz did not make a clear statement on this question.

Ratification by the law on the conclusion of peace between Germany and the Allied and Associated Powers finally took place on July 9, 1919, with similar voting proportions. Only the majority of the members of the Bavarian Farmers' Union , who abstained in the first vote on the signing, now approved the ratification law.

Constitutional deliberations

State name

After the Constitutional Committee chaired by Conrad Haußmann (DDP) had carried out its deliberations, the second reading of the draft constitution (in the committee version) began on July 2, 1919 in the plenary session of the National Assembly. The USPD applied for the name of the German state to be changed from German Reich to German Republic . Your MP Oskar Cohn stated that this was the only way to make the break with the outdated earlier order clear. In addition, the word empire is translated as empire in French and English , which has a fatal echo of imperialism, which was believed to have been overcome. Sticking to the old designation should give the impression abroad that Germany still has an imperialist striving for power.

While the SPD approved the USPD proposal, Bruno Ablaß spoke out in favor of the DDP against the USPD's request . He justified this with the fact that the designation empire no longer stands for a monarchy and even with the national designation France no one would think that it was an empire, but that it was generally known that it was a republic.

Clemens von Delbrück from the DNVP went even further, criticizing the formulation “The German Reich is a republic. All state power comes from the people “in Article 1 of the draft constitution is an unacceptable radical upheaval.

State organization

In another debate on July 2, Cohn called for the USPD to form a unitary state instead of a federal state. A unified state structure without independent member states could work much more efficiently, and the member states are only a relic of the old monarchist times.

On this point, the speakers of the other parties countered his argument by pointing out that the current draft was already a clear step towards strengthening the power of the Reich. Emphasized were inter alia. the replacement of the influential house of states by the advisory Reichsrat , the creation of Reichspost and Reichsbahn and the abolition of Prussian special rights. Erich Koch from the DDP pointed out that it was precisely the states of Bavaria and Braunschweig , which were temporarily dominated by the USPD, that were particularly particularistic and thus made the steps towards strengthening imperial power more difficult. The USPD's demands are therefore implausible.

On July 22nd, the issue of state structure was dealt with again with regard to the question of the reorganization of the empire and the change in the borders of the states. The Constitutional Committee had proposed that changes could be made at the proposal of the federal states concerned with a simple majority and against their will with two thirds of the votes in the Reichstag and in the Reichsrat. The German nationals wanted to delete the latter option , so that only a change of border should be possible with the consent of the countries concerned. The SPD , Zentrum and DDP, on the other hand, wanted a simple majority to be sufficient for the formation of new states against the will of the states concerned. This was primarily aimed at plans to divide Prussia into several smaller federal states, as requested by parts of the Rhenish center. The SPD deputy Wilhelm Sollmann justified this with the fact that Prussia and Bavaria could prevent any change against their will by working together in the Reichsrat. This is not appropriate. The Trier center delegate Ludwig Kaas even feared that the rejection of the proposed amendment could lead to the separation of the Rhineland from the German Reich. The Rhenish DDP member Bernhard Falk , a supporter of the unified state solution, also spoke out in favor of the amendment because, from his point of view, there was a risk that the particularists in the Rhineland would otherwise separate from the Reich.

In contrast, Albrecht Philipp from the DNVP rejected the amendment. He had absolutely no objection if, for example, Braunschweig wanted to join the Prussian province of Hanover or if the Thuringian states were to be united into a unified federal state of Thuringia . However, he rejected a separation of the Rhine Province or Hanover from Prussia or the addition of Prussian areas to a "Greater Thuringia". The destruction of Prussia was the war goal of Germany's enemies and with the demanded possibility of changing the national borders even against Prussia's consent, Germany would be robbed of its backbone. Even Rudolf Heinze from the right-wing liberal DVP spoke out against a breakdown of Prussia, but held the proposals of the DNVP goes too far and called for the proposal of the SPD, Center and DDP with the proviso that the proposal would be approved, a change of the national borders against the will of the affected states for the next two years. The USPD chairman Hugo Haase , however, spoke out in this debate for a unitary state and against particularism. In the end, the majority of the National Assembly voted in favor of the proposal made by the parties in the Weimar coalition .

Flag question

Also on July 2, the colors of the empire were debated. The speakers from the SPD and the center spoke out in favor of black-red-gold , DVP and DNVP, on the other hand, for the old colors of the empire, black-white-red . The USPD demanded that Germany fly a red flag as a symbol of revolution. At the DDP, the majority supported the previous flag, but a large minority spoke out in favor of the new colors.

Reich Minister of the Interior Eduard David (SPD) presented the view of the Reich government, according to which speak for black, red and gold, that it is the colors of the greater German national togetherness. They are the colors of the original fraternity and also of the revolution of 1848 . Black-red-gold stand for the desire for German unity instead of small states. Black-white-red, on the other hand, stands for the small German, Prussian-dominated solution of 1871.

On behalf of the DVP, Wilhelm Kahl replied that he did not consider a change of the imperial colors necessary and that it was wrong in terms of content. In particular, black-white-red did not stand for imperialism and oppression, but for the services that Prussia had to Germany and for the imperial unity of 1871, while black-red-gold stood for the failure of the imperial idea of 1848. Anyone who replaces black-white-red with black-red-gold ensures that large sections of the population must be hostile to the new order from the outset.

Wilhelm Laverrenz (DNVP) also alluded to the unification of the Reich in 1871. But he went even further and denied the colors black-red-gold to stand for the entire people. The soldiers in the World War fought for black-white-red and were enthusiastically welcomed with these colors after their undefeated return. The government should not take these colors away from the people. Black-red-gold, on the other hand, embodied the failure of 1848 on the one hand, and on the other hand it was worn by the enemies of Prussia in the civil war of 1866. Like Kahl, he also pointed out that black-white-red was more suitable as a trade flag, since it could be seen from afar at sea. Two flags - one for the state and one for the merchant navy - would not make sense, even if the SPD, the center and the DDP would apply for it, since it could not be made clear to anyone in a foreign port why the German consulate wears a different flag, than the ship at anchor in the same place.

Carl Wilhelm Petersen from the DDP spoke out in favor of keeping the old black, white and red colors, but also showed respect for those MPs who would have chosen black, red and gold in memory of the bourgeois revolution of 1848. He criticized the exaggeration of the question by the speakers of the other parties and called for more to be seen of the practical implications. In his view, a flag change would primarily endanger foreign trade, because black-white-red stands for German hard work and German quality goods, while black-red-gold is unknown abroad.

For the USPD, Oskar Cohn justified the motion to use red as the color of the German state by saying that red is the color of the revolution and the idea of freedom. Any progress is associated with the color red.

This debate already indicated that the flag and color dispute would continue after the constitution was passed. Hermann Molkenbuhr of the SPD accused Petersen of Hamburg that after the unification of the empire in 1871 the Hanseatic merchants fought against black-white-red and for the old flags of the Hanseatic cities, with which they now switched to black and red, with the same trade-policy arguments -Gold is being fought. But even the change of flag at that time did not damage export and merchant shipping.

Ludwig Quidde , who later won the Nobel Peace Prize, presented the views of those in the DDP who were in favor of black-red-gold. He also spoke out vehemently for a compromise on the trade flag and supported the motion to keep it in black, white and red, but to add a black, red and gold jack to it.

As a result of the debate, the colors black, red and gold were adopted by a large majority as the new German national colors on July 3, 1919, with 211 votes and 90 votes against.

Reich President's Office

On July 4th the question of the Reich President was discussed among other things. While Hugo Haase spoke out in favor of the USPD against the office of Reich President and preferred a collegial government, on the other side Albrecht Philipp ( DNVP ) called for the Reich President to be given even greater power than the governing parties had planned. In addition, he wanted to limit eligibility - analogous to the US constitution - to those people who were born as German. However, both proposals were rejected.

On July 22nd, the question was discussed whether members of the houses that governed the individual states until 1918 should be eligible for election as Reich President. While the two social democratic parties wanted to exclude this, the center , DNVP , DVP and DDP spoke out in favor of not including this passage in the constitution, as it was up to the people to decide for themselves who to vote. However, they could not prevail.

Referendums, referendums and referendums

The debate on July 7 was dominated by the question of referenda . While Rudolf Heinze spoke out in favor of the DVP against any kind of popular legislation and Simon Katzenstein ( SPD ) wanted to see this expanded compared to the draft constitution and was supported by Oskar Cohn ( USPD ), Clemens von Delbrück announced that the DNVP was on this issue split: There are supporters who trust in the persistent forces in the people, while other parts of the parliamentary group speak out strictly against the people's legislation. He himself represented a middle position and was of the opinion that in cases in which the Reichstag and Reichsrat could not find an agreement, the referendum was a good opportunity for the people to decide on this dissent. He also spoke out in favor of a regulation that would give the Reich President the right to let the people decide on laws passed by the Reichstag. However , he rejects the referendum .

Reich Interior Minister Hugo Preuss for the Reich government and Erich Koch for the DDP basically supported the people's legislation including the referendum in the form of the draft constitution, but spoke out against individual aspects of the SPD proposal that went too far for them.

In the end, none of the various amendments received a majority, so that the people's legislation was finally passed in the form of a committee proposal.

Imperial Administration

Also on July 7th, the section on the Reich administration was discussed. The biggest changes compared to the regulations in the Kaiserreich were the determination that the German Reich finally formed a unified economic area and the establishment of legislative competence in tax law with the Reich. The standardization of the postal and railway systems, which restricted the rights of the southern German states in particular, was an innovation.

Administration of justice

On July 10, the National Assembly dealt with the administration of justice . Important innovations were the establishment of administrative jurisdiction and a state court as well as the limitation of military jurisdiction to times of war. The independence of the courts was also included in the constitution.

The USPD 's motion to create people's courts, however, was rejected by the other parties.

Fundamental rights and obligations: general

The discussion on fundamental rights and obligations began on July 11th. On the one hand, the question of whether fundamental rights and obligations should be included in the constitution was at issue, and on the other, which ones are at stake. The text presented by Friedrich Naumann to the committee was rejected by all parties as too lyrical.

For the DVP , Rudolf Heinze expressly spoke out against a catalog of fundamental rights in the constitution. Such a move too strongly in the powers of the individual states and also in the private autonomy z. B. between employer and employee. In addition, the present catalog is too detailed and regulates matters that should be reserved for simple special legislation. He referred to individual provisions from disciplinary law and criminal procedural law , which were now given constitutional status without need.

For the DDP , Erich Koch argued that the basic rights are merely guidelines and limits of legislation and should not intervene directly in the individual legal relationships. Even the DDP, although a supporter of such a catalog, considers the basic rights catalog to be too extensive. In order for the constitutional deliberations to come to an end quickly, the present catalog should be passed unchanged if possible, it is a compromise that contains a few shortcomings, but is still acceptable overall.

Reich Minister Hugo Preuss criticized the expansion of the catalog of basic rights in the constitutional committee compared to the draft. He must therefore - literally - deny "the paternity of fundamental rights" in the name of the Reich government. He demanded a self-restraint on the part of the constitution, stating that everything cannot and must not be regulated in the constitution. The example of the Paulskirche constitution of 1849, which ultimately failed because of the ongoing dispute over basic rights, calls for humility.

The Bavarian center delegate Konrad Beyerle , one of the authoritative authors of the expanded catalog of basic rights, defended it against the accusation of arbitrariness. It is important to anchor elementary truths of legal culture in the constitution and to lift them out of the everyday life of ordinary legislation. It is also important to include the new state's confessions in the constitution. This is done through basic rights and basic duties. Beyerle received support in this view from the social democrat Max Quarck , who also referred to the educational effect of the fundamental right. Quarck, however, spoke out in favor of examining whether the catalog still needed some changes in one place or another. Sufficient requests have been made that should not fall victim to Koch's demand for unchanged acceptance en bloc.

Fundamental rights and obligations: individual advice

On July 15, the individual counseling on fundamental rights began. The Social Democrat Marie Juchacz spoke out in favor of comprehensive gender equality - and not just a "fundamental" one like the draft constitution - as well as the abolition of any nobility predicates. Luise Zietz from the USPD argued in the same way, but wanted equality to be extended to the area of civil law.

In her reply, Christine Teusch from the center , at the age of 30 the youngest member of the assembly, rejected full equality because "one has to do justice to the basic physical and psychological disposition of women," said Teusch literally.

For the DDP , Hermann Luppe spoke out in favor of following the draft version and retaining titles of nobility only as part of the name, without being able to derive privileges from it. He justified this with the fact that with many additions to names, he especially mentioned Ludwig van Beethoven , it was completely unclear whether they were titles of nobility or not. If the USPD and SPD were to follow suit, it would therefore be unclear for many people what name they should now use. With regard to the full equality of men and women, he also pleaded for the committee version, after all women could not and would not be called up for military service, which would also mean that they would have to be deprived of the right to become officers in an army that was already closed to them can.

Count von Posadowsky-Wehner argued for the German Nationals both for the preservation of the nobility and, above all, for the further award of orders and decorations, for the latter mainly because they were an acknowledgment of the state for services rendered. Representative Rudolf Heinze also supported this view for the People's Party .

On behalf of a minority within the two right-wing parties DVP and DNVP, Oskar Maretzky spoke out in favor of the abolition of any nobility designations, he represented the self-confident bourgeoisie, who see more harm than good in the nobility.

Since none of the numerous amendments could get through, the later Article 109 was finally adopted in the draft version. There were also no changes to the text of Article 110, which deals with citizenship law and other fundamental rights articles dealt with on that day.

death penalty

The debate began on July 16 with the question of the death penalty . For the Social Democrats , the law professor Hugo Sinzheimer justified the demand that the wording “The death penalty has been abolished”, as it is contained today in the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, be included in the Reich constitution. He was supported on this point by Oskar Cohn ( USPD ).

The German nationalists Adelbert Düringer and Franz Heinrich Költzsch as well as Wilhelm Kahl from the DVP spoke out vehemently against the abolition of the death penalty . While Kahl admitted that there could come a time when the death penalty could be waived, but this had not yet been reached, the two DNVP MPs rejected the abolition of the death penalty in principle. While Düringer limited himself to legal aspects, Pastor Költzsch justified the death penalty theologically and cited that the Bible already demands that whoever sheds human blood should also be shed by humans.

On behalf of the DDP , Conrad Haussmann called for the death penalty to be abolished, but was of the opinion that this question should be reserved for a simple legal regulation within the framework of the criminal law reform and should not be included in the constitution.

The National Assembly rejected the proposed abolition of the death penalty in the constitution by 153 votes to 128, with two abstentions.

censorship

On the same day, Franz Heinrich Költzsch spoke out in favor of a constitutional provision that offered the necessary protection against “rubbish and dirt”.

Otto Nuschke replied on behalf of the Democrats that the general criminal laws were sufficient to combat pornographic films, plays and literature. The censorship , as demanded by the German Nationals, is a relic from the time of the Karlovy Vary resolutions . The USPD MP Wilhelm Koenen also rejected any form of censorship, but demanded that performances for young people should be reserved for the authorities and non-profit organizations, because at least the young should be protected from the profiteering of the “capitalists”.

While the USPD's application was rejected, the assembly complied with the DNVP's request that at least for films a censorship regulation, which could be implemented by a Reich law, was permissible. This regulation was later introduced by the law for the protection of young people from trash and dirty writing of December 18, 1926.

Family law

Later that day, the meeting considered the issue of equality between illegitimate mothers and children and wives and legitimate children. The social democrat Elisabeth Röhl called for complete equality. She was supported in this view by Luise Zietz ( USPD ).

The founder of the social service of Catholic women Agnes Neuhaus ( center ) rejected such far-reaching demands for her party. Certainly one has to help the children in particular, but complete equality would blur the difference between marriage and the “illegitimate relationship” and is therefore unacceptable from a Christian point of view.

Elisabeth Brönner supported the demand for the DDP to improve the situation of illegitimate children and mothers. However, full legal equality does not make sense because it overshoots the mark and poses new problems. More important and more correct than complete equality, which is not practicable, is therefore the anchoring of a special duty of care of the state for mothers in general. This affects both illegitimate and particularly large mothers.

For the German Nationals , Anna von Gierke rejected the present applications from the SPD, USPD and DDP. The equality of illegitimate mothers with wives and illegitimate children with legitimate children is a devaluation of the family. She is always ready to alleviate individual emergencies, but this should not ruin the social coexistence that is characterized by marriage. In order to give mothers better opportunities to raise their children, she supported the demand for an upbringing allowance or a minimum wage for the fathers, which had to cover the subsistence level of the family.

After a lively debate, the National Assembly rejected the motions of the SPD, USPD and DDP as well as a motion by the USPD to nationalize the entire health system and place it under a Reich Ministry of Health.

Child care

The session began on July 17, 1919 with the debate about child welfare. Wilhelmine Kähler called for centralized child welfare for the SPD by the Reich and for all private and denominational welfare institutions to be replaced by state institutions. In addition, only qualified educators and pedagogues are allowed to act as heads of such institutions. She was supported by Lore Agnes ( USPD ) who, in addition to expanding state welfare, also called for a ban on the institutionalization of children and young people for political or religious reasons.

In contrast to the representatives of the political left, Agnes Neuhaus from the Catholic Center emphasized the advantages, from her point of view, of denominational youth welfare over state welfare. The denominational institutions are more efficient and more successful than the state homes. Therefore, only supervision should remain with the state. She found support from the German national Anna von Gierke , who, from a Protestant point of view, pleaded for Christian youth welfare and recalled Bodelschwingh in Bethel and Wichern's Rauhes Haus .

Erich Koch ( DDP ) spoke out against the restriction of the management of youth welfare institutions to trained educators and educators and referred to the example of Pestalozzi , who could never have worked as a “simple farmer” under such a regulation.

With a majority of the bourgeois parties, the National Assembly rejected the motions of the SPD and USPD, while a center motion to emphasize the role of the family in education was rejected by the SPD, USPD and DDP and thus also failed.

Right of assembly

The National Assembly then devoted itself to the right of assembly . Gustav Raute called for the USPD to delete the passage that made it possible to register for meetings in the open air. He compared this provision with the old law on associations, which made assemblies subject to approval.

Hugo Preuss turned against this demand on behalf of the Reich government . An obligation to register is necessary because, for security reasons, the administration has to know who is marching where and when; this has nothing to do with a permit requirement.

Civil service law

The following debate about civil service law was less about the question of how this should be structured than about whether special provisions in the constitution were required or whether a simple statutory provision would not suffice. While the Social Democrats and the USPD demanded the most extensive provisions possible in the constitution, the bourgeois parties only spoke out in favor of detailed regulations in the special legislation.

There was a real dissent in terms of content on the question of how the officials should be selected: While Oskar Cohn called for the election of the officials for the USPD , this was rejected by the other parties.

Opinions also differed on the question of whether female civil servants should leave the service if they got married. While the draft constitution wanted to keep the so-called celibacy of female teachers , the Social Democrat Toni Pfülf called for its abolition because it was unjust and opposed to equality between men and women. She also found the support of the left-liberal Marie Baum , the right-wing liberal Clara Mende and the USPD . On the other hand, Maria Schmitz ( center ), the chairwoman of the Association of Catholic German Teachers , supported the committee version, but was unable to prevail.

Church and State

The issue of church and state , which was dealt with on the afternoon of July 17th, brought about major disputes .

While the Protestant law professor Wilhelm Kahl ( DVP ) advocated the regulations proposed in the committee, as they are mostly still in force today, and saw a clear separation of church and state in this , Max Quarck called for an even stronger separation for social democracy .

The DDP chairman and Protestant pastor Friedrich Naumann saw the beginning of the separation of church and state, especially for the Protestant regional churches, as the dawn of a new era, since the Protestant church has so far been much more closely interwoven with the state in the federal states in which it had been the state church was than the Roman Catholic Church. However, he pointed out that there are also many members in the regional churches who continue to want state protection. However, since the protective state is also an oppressive state, it advocates the separation of the church from the state. However, at least for Protestantism with its 22 regional churches, this is a slowly developing process that needs time.

The German national delegate Karl Veidt , also a Protestant pastor, replied that he would "not sing a jubilee hymn" because of the separation of church and state. One must consider that the state church had its good, the Protestant regional churches were truly national churches. In addition, the territorial organization had ensured that the individual communities, which had initially drifted apart, were brought into a unified organization after the Reformation.

The USPD MP Fritz Kunert, on the other hand, called for a complete separation of church and state, so the right to collect church taxes must be abolished and the religious communities should not retain the privilege of performing religious acts in the military, in prisons and hospitals. Finally, he demanded that church property should be used to finance state tasks through increased taxation.

It was noticeable that the center hardly took part in this debate. Only Joseph Mausbach appeared as rapporteur for the constitutional committee and presented the course of the deliberations in the committee. Apparently the Catholics felt less affected by the new regulations than the Protestants.

Educational policy

The field of education policy was the subject of the discussions on July 18. This field of politics was also overshadowed by the question of the relationship between church and state , since the question of religious instruction and church school supervision was almost exclusively controversial. While the political left wanted to completely eliminate the influence of the church on the school, the center , DVP and DNVP campaigned for the maintenance of the church's influence to varying degrees.

The SPD deputy Heinrich Schulz and center parliamentary group leader Adolf Gröber presented the Weimar school compromise to their parliamentary groups, according to which the question of confession should be left open and the parents themselves should decide on the establishment of denominational schools , simultaneous schools or secular schools in each community .

Richard Seyfert from the DDP - later Saxony's education minister - spoke out in favor of a state school free of denominations, in which religious instruction alone should be given separately according to denomination under the responsibility of the religious communities. The DNVP MP Gottfried Traub , who defended the denominational school, strongly opposed this . In addition, Traub, who would later become one of the leading figures in the Kapp Putsch , advocated that “all circles of the people should receive a purely national education”.

In contrast, the Bavarian Center Member Martin Irl supported the compromise line between his party and the Social Democrats in principle, but called for some modifications, e.g. B. Concerning the minimum compulsory education of eight years. However, he was unable to assert himself.

The DVP parliamentarian August Beuermann spoke out against the parents' freedom of choice in the school issue because he feared that this would reopen the cultural war of the 19th century and bring strife into the communities at the expense of the children.

Relationship between state, economy and property

The debates on July 21 revolved around the relationship between the state and the economy. The majority in the Constitutional Committee had spoken out in favor of placing the economic freedom of the individual under the primacy of guaranteeing a decent existence for all and placing the principle of justice in the foreground of economic life. Economic freedom must fulfill a social function. Freedom of contract , property and the right of inheritance should be guaranteed, but subject to the proviso of the law , said the SPD MP Hugo Sinzheimer as the committee's rapporteur. The ban on usury and the nullity of immoral legal transactions should be given constitutional status.

The constitutional committee had also spoken out in favor of the social obligation of property and a fundamental anchoring of inheritance tax in the imperial constitution. The social obligation also resulted in the introduction of the possibility of nationalizing companies, the participation of the public sector in company administration and the state's objection to "socially adverse" company decisions proposed by the constitutional committee. The latter instrument should work against business cartels and trusts in particular .

The creation of a uniform labor law was postulated as a national goal in the draft . While the committee was unable to agree on a constitutional safeguard for the right to strike , freedom of association should be given constitutional status. In addition, workers 'councils should be created to represent the interests of the workforce and business councils as joint organs of employees and employers , without replacing the previous trade unions and employers' associations . The Reich Economic Council should have its own right of initiative to the Reichstag .

In the debate, USPD MP Alfred Henke criticized the committee draft . He criticized the fact that there was no “socialist spirit blowing through the lines”, but that the bourgeois worldview asserted itself in the constitution. He prophesied that capitalist exploitation would continue. This is precisely because the draft constitution guarantees ownership of the means of production . The constitution ultimately aims to preserve capitalism. Therefore the revolution must not be ended. Regardless of the possessing classes, the realization of socialism must begin immediately. The USPD therefore requested that large parts of the economic constitution be deleted and stipulated that the means of production and the production of goods should be socialized. However, they failed with their corresponding applications.

On behalf of the DVP , Rudolf Heinze demanded that legal action should be opened in the event of expropriations over the amount of the compensation in order to enable a judicial review. In addition to this, the center requested that expropriations by the Reich vis-à-vis the federal states, municipalities and non-profit associations should only be permitted in return for compensation. His deputy Johann Leicht justified this with the fact that the property of these corporations was already in the service of the general public, which is why it was out of the question to come to expropriations without compensation. While the center was able to prevail with its application, the DVP's request for a guarantee of legal recourse was rejected.

The SPD deputy Nikolaus Osterroth applied for his parliamentary group to stipulate that all mineral resources and natural forces should be transferred to common property . Private shelves and usage rights are to be canceled without compensation. He vehemently contradicted the more radical demands of the USPD and countered Alfred Henke with the sentence “(...) we don't imagine socialism like some people who carry half a pig home from the secret slaughter and believe that it is socialism”. He also accused the Independent Social Democrats of destroying the united front of the working people. Albrecht Philipp of the DNVP spoke out against the socialization of natural resources , who feared that sooner or later every soil yield could be viewed as a “natural resource” and thus the yields of agriculture could also be socialized. For the left-liberal DDP , its MP Fritz Raschig also rejected the expropriation of the shelves and rights of use without compensation, his faction prefers a regulation that puts natural resources only under the supervision of the state. This DDP motion was rejected by the majority on all points. In contrast to the question of the collectivization of natural resources and natural forces, the SPD motion to lift private shelves and rights of use found a narrow majority (132 votes in favor, 118 against, one abstention).

August Hampe , the only member of the welfisch-oriented Braunschweig-Lower Saxony party , spoke out against the lifting of entails , as the constitutional committee had planned. The Fideikommiss is a successful Germanic legal idea. Its abolition would lead to considerable upheaval and, in particular, to the migration of important cultural assets abroad, especially to America. He was supported in this demand by the Hessian DVP MP Johann Becker , who saw a particular danger for medium-sized and small-scale agriculture, since the farm and inheritance rights of individual countries, which would protect against the fragmentation of farms, would also have a fideicommissary character this constitutional provision is also endangered. The SPD MP Simon Katzenstein, on the other hand, defended the committee version as necessary to counteract the agglomeration of ever larger amounts of land in the hands of a few private individuals. Felix Waldstein from the DDP contradicted Becker in particular on the assumption that farm and inheritance rights were also affected. He supported the abolition of entails, because they only had the goal of giving help to the inefficient, instead of giving the able a free run. The applications for receipt of entails were all rejected by the majority.

There were also discussions about how to deal with increases in land value that were not earned through the use of labor or capital. While the left-wing parties wanted to fully benefit the state, Hermann Bruckhoff applied for a restriction for the DDP to the effect that this increase in value should only be made “usable for the whole”. The DDP application was also supported by the right-wing liberal DVP, while the DNVP only wanted to allow the increase in value to be skimmed off through taxation. The majority of the National Assembly followed the DDP proposal, so that the committee proposal was changed in this respect.

The DNVP parliamentary group applied for a formulation to be included, according to which the protection of the middle class from exploitation and absorption is an important task of the legislature and administration. Your MP Wilhelm Bruhn justified this with the fact that the middle class had been hit particularly hard by the world war . In addition, big business particularly threatens small and medium-sized businesses. One example is the establishment of department stores, which had a devastating effect on small retailers. After the word "exploitation" was changed by "overloading" in the DNVP application at the request of the DDP, the application was accepted by a majority.

There were also major discussions about the constitutional anchoring of the workers' and economic councils. The DNVP MP Clemens von Delbrück saw it as a “child of the Russian Revolution”, which the German Nationals were fundamentally opposed to. The Reichswirtschaftsrat could still be seen as a good thing, namely, as the professional chamber of the entire creative people, it was a "counterweight to the over-tension of parliamentarism and the rule of parliament". Anton Erkelenz from the DDP supported the introduction of workers' and business councils, but he refused to give the councils decision-making or control powers; they should only have an advisory role. The USPD MP Wilhelm Koenen, on the other hand, demanded that the workers' councils have the right to veto legal decisions. In addition, the workers should have a preponderance over the employers in the economic councils. Center member Franz Ehrhardt turned against both proposals, who saw a threat to public life as a result.

adoption

On July 31, 1919, after making significant changes to the original draft, the National Assembly adopted the Weimar Constitution with a large majority. There were 262 votes in favor (from SPD, DDP, Zentrum), 75 against (from DVP, DNVP, Bavarian Farmers' Union, USPD) and 1 abstention. Thus, the constitution received an approval of 77.5 percent.

further activities

taxes and finances

The Weimar National Assembly was not only busy drafting a constitution, but also acted as a parliament and exercised its legislative function. For example, the entire revision of finance and taxation was initiated by a keynote speech by the Reich Minister of Finance, Matthias Erzberger from the Center Party , on July 8, 1919. Formally, the consultation only dealt with the first reading of ten tax laws, but its effect went far beyond that. With the passing of the law on the payment of tariffs in gold of July 19, 1919, which was passed with a large majority and only against the votes of the USPD , the import tariffs (except for the food tariffs abolished in 1914) were restored to their actual value Brought pre-war status.

miscellaneous

With the passing of the Reich Settlement Act on July 19, 1919, a first step towards land reform was taken. On the same day, the allotment garden and small leasehold regulations were passed.

From September 30, 1919, the National Assembly met in the now renovated Reichstag building in Berlin. During the Kapp Putsch, it briefly escaped to Stuttgart and met there on March 18, 1920. The National Assembly dissolved on May 21, 1920. After the Reichstag election on June 6, 1920, the 1st Reichstag took the place of the National Assembly.

On January 13, 1920, while the National Assembly was negotiating the Works Council Act in the second reading , a demonstration against the law took place in front of the Reichstag building. The left opposition parties USPD and KPD called for this, and around 100,000 people gathered. The security team of the building shot into the crowd after individual fights, 42 people died and over 100 were injured. It was the bloodiest demonstration in German history .

literature

- Heiko Bollmeyer: The rocky road to democracy. The Weimar National Assembly between the Empire and the Republic. (= Historical Political Research. Volume 13). Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2007, ISBN 978-3-593-38445-0 .

- Axel Weipert: At the gates of power. The demonstration in front of the Reichstag on January 13, 1920. In: Year Book for Research on the History of the Labor Movement . Volume 11, Issue 2, Verlag NDZ, Berlin 2012, ISSN 1610-093X , pp. 16–32.

- Rainer Gruhlich: History politics under the sign of collapse. The German National Assembly 1919/20. Revolution - empire - nation . Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 2012, ISBN 978-3-7700-5309-4 .

Web links

- Text of the Reichstag Election Act of November 30, 1918

- Birte Förster , Mareike König, Hedwig Richter : Parliamentarians in the Weimar National Assembly in 1919 - portraits in 280 characters. In: hypotheses.org , June 26, 2019.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Heiko Holste: The National Assembly belongs here! In: FAZ, Bilder und Zeiten. No. 8, January 10, 2009, Z1

- ^ Reichstag building in the Weimar Republic , information from the German Bundestag on the Reichstag building, accessed on March 18, 2017.

- ↑ For the demonstration, see the detailed study by Axel Weipert: Before the gates of power. The demonstration in front of the Reichstag on January 13, 1920. In: Yearbook for research on the history of the labor movement. 11th year, issue 2, Berlin 2012, pp. 16–32.