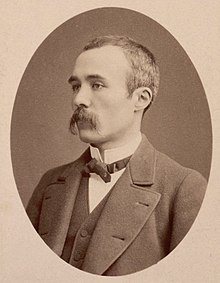

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau [ ʒɔʀʒ bɛ̃ʒaˈmɛ̃ klemɑ̃ˈso ] (born September 28, 1841 in Mouilleron-en-Pareds , Département Vendée , † November 24, 1929 in Paris ) was a French journalist , politician and statesman of the Third Republic . As one of the leading representatives of the left-wing Parti radical , he was French Prime Minister from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 to 1920.

He emerged in 1899 as an advocate for a retrial to rehabilitate Alfred Dreyfus . In 1919, after the First World War , he was one of the "Big Four" at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 , where he called for a tough policy towards Germany .

Life

Georges Clemenceau first studied medicine in Nantes and Paris. He became politically active in Paris and founded his first newspaper Le Travail with political friends . The newspapers La justice, L'Aurore, Le Bloc and L'Homme libre followed later . He was decidedly anti-clerical and opposed the Second Empire as a staunch supporter of the republic , which is why he was arrested several times for a short time.

From 1865 to 1869 he worked as a journalist and teacher at a girls' school in Stamford , Connecticut , where he married his former student Mary Plummer in 1869 and had three children with her. The marriage ended in divorce after seven years.

In 1870 he returned to France and in the same year became mayor of Montmartre . In 1871 he was elected to the Chamber of Deputies as a member of the Radical Socialists . As a radical nationalist , he voted against peace with Germany in 1871 . Since its conclusion and the cession of Alsace-Lorraine as agreed therein , he has endeavored to keep alive the thought of revenge on Germany. That is why he spoke out firmly against the colonial policy of Prime Minister Jules Ferry , which in his opinion would distract from the political goal of the “blue ridges of the Vosges ”. Because of this and as an anti-clerical, he earned a reputation in his party and became the most prominent representative of the political left in the Third Republic. In 1876 he became chairman of the Radical Socialists. In 1885 he overthrew the Ferry cabinet and was nicknamed "le tigre" (the tiger). In connection with the Panama scandal , he was not re-elected to the chamber in 1893. During the Dreyfus Affair , he campaigned for the convicted officer as owner and editor of the magazine L'Aurore, together with Jean Jaurès and Émile Zola . Zola's famous J'accuse appeared in L'Aurore in 1898 . In this crisis, which deeply shook the republic, Clemenceau became one of the most important politicians in France.

In 1902 Clemenceau was elected to the Senate , in 1906 he became Minister of the Interior in the cabinet of his party friend Ferdinand Sarrien . In this capacity he used the military against striking miners in the Pas-de-Calais department in 1906 , which alienated him from the Socialist Party , with which he definitely broke in his response to Jean Jaurès in parliament. Clemenceau was Prime Minister from 1906 to 1909 . During this time he pushed through the final regulation of the separation of church and state . Clemenceau continued the military policy of his predecessor Émile Combes : in order to take control of the army, which had been the refuge of anti-republican reaction since the Dreyfus Affair , the civilian oversight of the state over the military was tightened and the power of the Minister of War over the military Commander enlarged. Despite his anti-colonialism, he strove for the increasing influence of France in initially still independent Morocco , which in 1905/06 conjured up the first Moroccan crisis with the German Empire. Domestically, the introduction of the income tax was the most important decision in Clemenceau's first term. In 1909 he fell over a marine scandal. In the following years and during the First World War , Clemenceau was again mainly active as a newspaper publisher. In 1913, he turned down the offer of his domestic rival, President Raymond Poincaré of the liberal-conservative Alliance démocratique (ARD), to make him ambassador to London - Poincaré had only submitted it to weaken the number of his anti-clerical opponents, whose attacks he followed up feared his church marriage. In 1913 he voted as one of 36 senators against the extension of compulsory military service from two to three years, among other things because this would increase the risk of war with Germany; the other 244 senators voted in favor.

The 76-year-old Clemenceau took over the office of Prime Minister on November 16, 1917. In the face of mutinies in the army and strikes among the workers, he was supposed to find a way out of the crisis and prevent a negotiated peace with Germany, whose protagonist was his party friend Joseph Caillaux . Clemenceau, who was also the minister of war at the time , ruled with a hard hand: there has been no opposition since the Union sacrée was formed. Now rule was concentrated on the person of Clemenceau, parliament was largely switched off or disciplined by threats of resignation and questions of confidence , and sharp censorship measures suppressed any defeatism . This is why there is often talk of a “ dictature Clemenceau”, which the historian Henning Köhler considers to be misleading in view of the large majority that the government had in both chambers of parliament.

With the publication of the Sixtus Letters - which had been sent to the French government by Prince Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma , brother of the Austrian Empress Zita , with a secret compromise offer from Emperor Karl I - he drove a wedge between the Central Powers in April 1918 Germany and Austria-Hungary.

During the negotiations for an armistice , for which Germany had asked American President Woodrow Wilson on November 6, 1918 , Clemenceau was able to enforce France's right to reparations . At first he did not think of a complete reparation for all war damage caused by Germany, but only of the pensions for war invalids . The fact that the French troops advanced as far as the Rhine, as Marshal Ferdinand Foch in particular had demanded, was not part of the armistice conditions . Nevertheless, Clemenceau reached the height of his popularity with her signing on November 11, 1918 and was celebrated nationwide as "Père la Victoire" ("Father Victory").

On February 19, 1919, Clemenceau was shot by the anarchist Émile Cottin. The successful French surgeon Gosset, a friend of Ferdinand Sauerbruch , removed the revolver bullet that was stuck on the right edge of the main artery. Clemenceau recovered quickly, mocked the poor marksmanship and pardoned the condemned man to prison.

At the Paris Peace Conference in Versailles in 1919, Clemenceau appeared as a staunch opponent of Germany. He wanted to protect France's interests by weakening Germany as much as possible. He demanded the cession of Alsace-Lorraine, the Saar region and the Rhineland and also demanded extensive reparations: "L'Allemagne paiera", "Germany will pay", of this the French public was convinced in the spring of 1919, especially since German reparations promised the social ones To alleviate tensions that had also broken out in France after the end of the World War. Because the United States insisted on repaying the Allied war debts it had lent to its European allies during the war and considering the mood of public opinion in France, where elections were due in November 1919, Clemenceau insisted on a minimum and a maximum determine the annual payments that Germany would have to make; the total amount can then be determined later by experts. The British Prime Minister David Lloyd George strongly opposed an excessive weakening of Germany because he feared a hegemony of France that would upset the balance of power on the European continent. He also feared that overly harsh peace conditions would bring Germany to the side of the Bolsheviks, which seemed entirely possible in view of the attempted communist overthrow in Hungary . However, he agreed to an expansion of German payment obligations. President Wilson was against Clemenceau's plans for an unlimited German reparation obligation as well as against the separation of the Rhineland: he wanted to “make the world safe for democracy”, and he saw this achieved in Germany with the fall of the monarchy . Clemenceau, on the other hand, did not believe that the Germans had changed their national character: for him they all remained " boches ". Nevertheless, he finally gave in to the security policy demands of the Anglo-Saxons, because they promised him to conclude guarantee treaties with France: If Germany were to attack France again in the future, it would automatically be at war with Great Britain and the USA. Under these conditions, Clemenceau finally signed the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919 . Because the United States Congress refused to ratify the peace treaty on March 19, 1920 , these guarantee treaties did not materialize. Clemenceau's security policy had thus failed.

In the elections to the Chamber of Deputies in November 1919, the Left suffered considerable losses, Clemenceau's radical socialists lost over a hundred seats and only came to 86 of 601 members. A national bloc was emerging . In December 1919, the newly elected chamber revoked the government's special rights, which is seen as a sign of Clemenceau's last defeat: in January 1920 he failed to run as Poincaré's successor for the office of president. Not least because the left-wing Republican Aristide Briand had raised the mood against him, he was defeated by Paul Deschanel from ARD. As a result, Clemenceau bitterly withdrew from politics.

Clemenceau first traveled and then turned to writing. After biographies of Demosthenes and Claude Monet , with whom he was friends, he worked on a justification Grandeurs et misères d'une victoire ("Greatness and tragedy of a victory"), in which he defended the policy of his second term as Prime Minister and in the face of the failure Guarantees and Briand's German policy, which he considered too willing to compromise, warned of the dangers of German rearmament. Clemenceau died on November 24, 1929, his book was published posthumously.

Honors

The following were named after Clemenceau:

- the Clemenceau (R98) , a former French aircraft carrier

- the Clemenceau neighborhood in Cottonwood , Arizona

- Mount Clemenceau (3658 m) in the Canadian Rockies , named after Clemenceau in 1919

- the Champs-Élysées - Clemenceau station of the Paris Métro

Several streets and squares were named after Clemenceau, including

- the Place Clemenceau in the 8th arrondissement of Paris

- the avenue Clemenceau in Brussels

- Clemenceau Avenue in Singapore

- the rue Clemenceau in Beirut

- the rue Clemenceau in Montreal

Works (selection)

- Démosthène. Plon, Paris 1925

- Au soir de la pensée. Plon, Paris 1927

-

Claude Monet, les Nymphéas. Plon, Paris 1928

- German: Claude Monet. His friend's reflections and memories. Urban, Freiburg 1929

-

Grandeurs et Misères d'une victoire. Plon, Paris 1930

- German: Greatness and tragedy of a victory. Union Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft, Stuttgart 1930

Individual evidence

- ^ Raymond Poidevin and Jacques Bariéty: France and Germany. The history of their relationships 1815–1975. CH Beck, Munich 1982, p. 144.

- ↑ Christopher Clark : The Sleepwalkers. As Europe moved into the First World War . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2013, p. 80.

- ↑ Christopher Clark: The Sleepwalkers. As Europe moved into the First World War . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2013, p. 403.

- ^ Raymond Poidevin and Jacques Bariéty: France and Germany. The history of their relationships 1815–1975. CH Beck, Munich 1982, p. 280.

- ^ Clemenceau, Georges . In: dtv lexicon on history and politics in the 20th century , ed. v. Carola Stern , Thilo Vogelsang , Erhard Klöss and Albert Graff, dtv, Munich 1974, vol. 1, p. 148.

- ↑ Nicolas Roussellier: Gouvernement et parlement en France dans l'entre-deux-guerres . In: Horst Möller and Manfred Kittel (eds.): Democracy in Germany and France 1918–1933 / 40. Contributions to a historical comparison. Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, p. 254 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Henning Köhler: November Revolution and France. The French policy towards Germany 1918–1919. Droste, Düsseldorf 1980, p. 25 f.

- ↑ Bruce Kent: The Spoils of War. The Politics, Economics, and Diplomacy of Reparations 1918–1932. Clarendon, Oxford 1989, p. 22 f.

- ^ Raymond Poidevin and Jacques Bariéty: France and Germany. The history of their relationships 1815–1975. CH Beck, Munich 1982, p. 297.

- ^ Henning Köhler: November Revolution and France. The French policy towards Germany 1918–1919. Droste, Düsseldorf 1980, p. 27.

- ^ Ferdinand Sauerbruch , Hans Rudolf Berndorff : That was my life. Kindler & Schiermeyer, Bad Wörishofen 1951; cited: Licensed edition for Bertelsmann Lesering, Gütersloh 1956, p. 306 f.

- ^ Raymond Poidevin and Jacques Bariéty: France and Germany. The history of their relationships 1815–1975. CH Beck, Munich 1982, pp. 301-312; Bruce Kent: The Spoils of War. The Politics, Economics, and Diplomacy of Reparations 1918–1932. Clarendon, Oxford 1989, pp. 66-82.

- ↑ Nicolas Roussellier: Gouvernement et parlement en France dans l'entre-deux-guerres . In: Horst Möller and Manfred Kittel (eds.): Democracy in Germany and France 1918–1933 / 40. Contributions to a historical comparison. Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, p. 254 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Raymond Poidevin and Jacques Bariéty: France and Germany. The history of their relationships 1815–1975. CH Beck, Munich 1982, p. 318 and 351.

literature

- Clemenceau, Georges . In: dtv lexicon on history and politics in the 20th century , ed. v. Carola Stern , Thilo Vogelsang , Erhard Klöss and Albert Graff, dtv, Munich 1974, vol. 1, 147 f.

Web links

- Lecomte, G .; Stuart, DC: Georges Clemenceau, the Tiger of France (1919)

- Literature by and about Georges Clemenceau in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Georges Clemenceau in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Anne-Cécile Renouard, Gabriel Eikenberg: Georges Clemenceau. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Short biography and list of works of the Académie française (French)

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

|

Ferdinand Sarrien Paul Painlevé |

Prime Minister of France October 25, 1906–24. July 1909 November 16, 1917-20. January 1920 |

Aristide Briand Alexandre Millerand |

|

Fernand Dubief |

Minister of the Interior of France March 14, 1906–24. July 1909 |

Aristide Briand |

|

Paul Painlevé |

Minister of War of France November 16, 1917-20. January 1920 |

André Lefèvre |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Clemenceau, Georges |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Clemenceau, Georges Benjamin |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French politician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 28, 1841 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Mouilleron-en-Pareds |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 24, 1929 |

| Place of death | Paris |