Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus Affair was a judicial scandal that deeply divided French politics and society in the last few years of the 19th century. They related to the condemnation of the artillery - Captain Alfred Dreyfus in 1894 by a military court in Paris for alleged treason in favor of the German Empire led the public in years of disputes and other legal proceedings. The conviction of the Alsatian- born Jewish officer was based on illegal evidence and dubious manuscript reports. Initially, only family members and a few people who had doubts about the guilt of the defendant in the course of the trial campaigned for the reopening of the trial and Dreyfus' acquittal.

The miscarriage of justice turned into a scandal that struck all of France. Highest circles in the military wanted to prevent Dreyfus' rehabilitation and the conviction of the actual traitor, Major Ferdinand Walsin-Esterházy . Anti-Semitic , clerical and monarchist newspapers and politicians incited sections of the population, while people who wanted to come to Dreyfus' aid were threatened, convicted or released from the army. The eminent naturalistic writer and journalist Émile Zola , for example, had to flee the country to avoid imprisonment. In 1898 with his now famous article J'accuse …! (I accuse ...!) Denounced that the guilty party was acquitted.

The newly formed government under Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau in June 1899 relied on a compromise, not a fundamental correction of the misjudgment, in order to end the disputes in the Dreyfus affair. Dreyfus was pardoned a few weeks after his second conviction. An amnesty law also guaranteed impunity for all violations of the law in connection with the Dreyfus affair. Only Alfred Dreyfus was exempt from this amnesty, which enabled him to continue to seek a revision of the judgment against himself. Finally, on July 12, 1906, the civilian Supreme Court of Appeal overturned the verdict against Dreyfus and fully rehabilitated him. Dreyfus was reassigned to the army, promoted to major and also made a knight of the French Legion of Honor . Major Marie-Georges Picquart , who had been transferred as a criminal offender , formerly head of the French foreign intelligence service ( Deuxième Bureau ) and a key figure in the rehabilitation of Alfred Dreyfus, returned to the army with the rank of brigadier general .

After the Panama scandal and parallel to the Faschoda crisis, the Dreyfus affair was the third major scandal in this phase of the Third Republic . With intrigues , forgeries, resignations and overthrow of ministers, lawsuits, riots, assassinations, the attempted coup d'état ( February 23, 1899 ) and increasingly open anti-Semitism in parts of society, the affair plunged the country into a serious political and moral crisis. Especially during the struggle to resume legal proceedings, French society was deeply divided, right down to the families.

course

The incriminating document

The cleaning lady Marie Bastian spied from time to time for the French intelligence service when she was working in the Palais Beauharnais , the then German embassy in Paris. On September 25, 1894, among other things, she stole a torn letter from the wastepaper basket of the German military attaché Lieutenant Colonel Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen . The French intelligence service put the letter back together; it was an unsigned letter accompanying a shipment of five secret military documents:

“Sir, although I have no word from you that you wish to see me, I am sending you some interesting information:

1. A record of the hydraulic brake of the 120 mm gun and of the experiences that have been made with it Has;

2. a record of the covering forces (the new plan will bring some changes)

3. a record of a change in artillery formations

4. a record of Madagascar

5. the draft field artillery firing code (March 14, 1894)

This final document is extremely difficult to get hold of, and can only be at my disposal for a very few days. The War Department has only sent a certain number of troops, and the troops are responsible for that. Each consignee among the officers must return his copy after the maneuvers. So if you want to copy what interests you and then keep the draft at my disposal, I will pick it up unless I have it copied in full and send the copy to you.

I am about to leave for the maneuvers. "

From this so-called bordereau , a list of attached documents, it emerged that a French general staff officer had leaked confidential information to the German secret service. The French foreign intelligence service forwarded the document directly to the French Ministry of War.

suspicion

Of the four department heads of the French General Staff, none of them could assign the handwriting of the bordereau to one of the officers under them. Lieutenant Colonel Albert d'Aboville therefore suggested focusing on the possible perpetrator profile. He was convinced that only an artillery officer could provide information about the 120-millimeter gun. Because of the variety of documents recorded, the author must be a graduate of the École supérieure de guerre , the Paris military college , which, following the École polytechnique and the Saint-Cyr military school , offered a select few a final degree.

The limitation to this group of people narrowed the circle of suspects considerably. Albert d'Aboville, together with Colonel Pierre-Elie Fabre, finally came to the conclusion that the handwriting was similar to that of the artillery captain Dreyfus. However, the clerk at the bordereau had mentioned in the last line that he was setting out on a maneuver. Dreyfus had never participated in a maneuver before. Both ignored this fact.

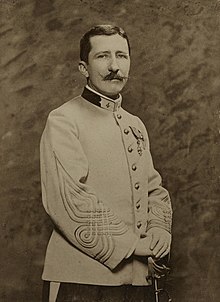

Alfred Dreyfus, born in 1859, came from a family of industrialists in Alsace . When, in 1871, after the Franco-Prussian War, his region of birth fell to Germany, his parents had decided to keep French citizenship and had relocated to Paris with parts of the family. Dreyfus began his service in the General Staff , where he was the first and only Jew, on January 1, 1893. He had graduated from the École supérieure de guerre as one of the best in his class, although he had received poor grades from his examiner General Pierre de Bonnefond in his final oral examination . The general justified this with the fact that Jews were not wanted on the General Staff. Dreyfus had failed to make friends on the General Staff. His superior, Colonel Pierre Fabre had certified him in an opinion acknowledged intelligence and talent, but also arrogance, inadequate behavior and character flaws wrote the writer Louis Begley 2009. Hannah Arendt called Dreyfus as a Jewish parvenu , the comrades against boasted with money and a part of it got through with mistresses , while his biographer Vincent Duclert describes him as a man of honor and a patriot.

arrest

Secretary of War Auguste Mercier , a moderate Catholic Republican who remained convinced of Dreyfus' guilt until his death, decided to press ahead with the investigation. This was not unanimously approved in the higher circles of government and army. The most senior French officer, General Félix Saussier , Republican of the center left, feared damage to the French army should one of its officers be charged with treason. According to the historian Henri Guillemin , he sponsored Esterhazy without knowing that he was guilty. The historian and Foreign Minister Gabriel Hanotaux warned of a strain on Franco-German relations if it became known that the French intelligence service had documents that had been stolen from the German embassy.

The moderate Republican President Jean Casimir-Perier also urged caution, as he doubted that the bordereau was sufficient as the sole evidence of a conviction for espionage. Prime Minister Charles Dupuy made War Minister Mercier promise not to bring proceedings against Dreyfus unless there was other evidence of guilt in addition to the bordereau. Mercier, who relied on the evaluations of his officers, saw no reason to change the course he had taken, and on October 14, 1894, he signed the arrest warrant for Alfred Dreyfus. Mercier entrusted Major Armand du Paty de Clam with the further investigations .

On October 15, Dreyfus was summoned to the Chief of the General Staff under a pretext, where du Paty was waiting for him and dictating sentences and scraps of sentences from the intercepted bordereau. He then confronted him with allegations of treason, arrested him on the spot, had him taken to Cherche-Midi prison and searched his house. Du Paty informed Dreyfus' wife Lucie that her husband was in custody, but refused to give her any further information. He forbade her to inform others about the arrest and threatened her with grave consequences for her husband if she did not follow these instructions. It was not until October 31, 1894 that she was given permission to notify her family of the arrest.

Dreyfus saw the Bordereau for the first time the day before and was then convinced of the baselessness of the allegations. He had not had access to any of the documents listed in the letter, and the prosecution could not identify a credible motive for treason. Lack of money, a frequent cause of such actions, did not apply to Dreyfus. Both Dreyfus and his wife came from wealthy families and had considerable personal wealth: while a lieutenant received an annual salary of less than 2,000 francs, Dreyfus's fortune alone produced an annual income of 40,000 francs.

A written report by the criminalist Alphonse Bertillon , who had been consulted as a script expert without the relevant knowledge , turned out to the disadvantage of Dreyfus. Bertillon insinuated that Dreyfus had altered his handwriting while drafting the document. On the instructions of Mercier, the judgment of other handwriting experts was obtained. Two concluded that there were similarities between the two manuscripts, and one found the match sufficient to attribute the Bordereau to Dreyfus. Two others thought the two manuscripts were not identical.

First press coverage

Just two days after you informed the Chief of Staff Raoul de Boisdeffre , who had been firmly against Dreyfus, that he had doubts about the success of a lawsuit, an informant from the War Department released details of the case to the press. On October 31, 1894, the daily newspaper L'Eclair reported the arrest of an officer, La Patrie had already mentioned the arrest of a Jewish officer in the War Ministry, and Le Soir announced Dreyfus' name, age and rank. War Minister Mercier, who had been severely attacked by the press on several occasions for other issues, was now in a difficult position, a quandary : If he had ordered Dreyfus to be released, the nationalist and anti-Semitic press would have accused him of failure and a lack of hardship towards a Jew . If, on the other hand, an acquittal had occurred in a trial, he would have been accused of having made careless and dishonorable accusations against an officer in the French army and of risking a Franco-German crisis. Mercier would then probably have had to resign, according to Begley. At a special session of the cabinet, Mercier showed the ministers a copy of the bordereau and claimed that Dreyfus was clearly the author. The ministers then agreed to initiate a judicial investigation against Dreyfus. The case now fell within the jurisdiction of the most senior French officer. General Saussier entrusted the further investigations to Captain Bexon d'Ormescheville, an examining judge at the Premier conseil de guerre , the highest court martial in Paris.

The German ambassador declared on November 10, 1894 in the newspaper Le Figaro that there had been no contact between the German military attaché Max von Schwartzkoppen and Dreyfus. Previously, the Italian military attaché Panizzardi had informed the Italian army headquarters in an encrypted telegram that he had no connection with Dreyfus. He had also recommended that the Italian ambassador should issue an official statement to prevent further press speculation.

The French postal authority intercepted the telegram, the Foreign Ministry's translation service deciphered it and handed it over to the intelligence service on November 11, 1894. Jean Sandherr , Head of Intelligence, made a copy and sent the original back to the Foreign Office. The copy was placed in the files of the War Department. The Hungarian writer, composer and playwright George R. Whyte , who dealt with the scandal in many ways, assumed in 2005 that this copy was exchanged for a wrong version on the same day. According to this forgery, the French War Ministry had evidence of Dreyfus's contacts with the German Empire. The Italian embassy had therefore already taken all necessary precautionary measures.

The tone of the press reports became significantly sharper in the course of November. La Libre Parole , L'Intransigeant , Le Petit Journal and L'Éclair repeatedly accused the ministers of failing to investigate the case vigorously because the accused was Jewish. On November 14, 1894, the leading Catholic anti-Semite and conspiracy theorist Édouard Drumont claimed in the nationalist and anti-Semitic newspaper La Libre Parole that Dreyfus had only joined the army to commit treason . As a Jew and German, he hates the French. The Catholic daily La Croix on the same day described the Jews as a terrible cancer that would lead France into slavery.

Shortly afterwards, War Minister Mercier stated in Le Journal that the investigation into Dreyfus would be completed within ten days. Eleven days later, an interview with Mercier appeared in Figaro showing that he had clear evidence of Dreyfus' treason. He indicated that the German intelligence service was the recipient of the secret documents. On the same day, the daily Le Temps published a denial from Mercier under pressure from Prime Minister Dupuy. Nevertheless, the German ambassador Georg Herbert zu Münster took the interview as an opportunity to complain to Foreign Minister Gabriel Hanotaux . He called it an allegation that his government had in some way given cause for the arrest of Dreyfus. On November 29, 1894, the Havas news agency published an ambiguously worded unofficial statement that Mercier's interview in Figaro was incorrectly reproduced.

The secret dossier

On December 3, 1894, Captain d'Ormescheville forwarded the investigation report that had been written together with Major du Paty to General Saussier. The evidence was limited to the Bordereau, Dreyfus' knowledge of German and a negative assessment of Dreyfus by some officer colleagues. D'Ormescheville did not mention the expert reports, who saw no similarity between the handwriting of Alfred Dreyfus and that of the Bordereau. Only Bertillon's report was listed.

In view of this thin evidence, General Saussier ordered his officers to collect in their archives all documents relating to espionage that could be used against Dreyfus. A secret dossier was compiled from this collection which contained the following documents at the time of the first court martial:

- Schwartzkoppen's fragmentary memorandum to the General Staff in Berlin, in which he obviously considered the advantages and disadvantages of working with an unnamed French officer who offered his services as an agent.

- A letter dated February 16, 1894 from the Italian military attaché Panizzardi to his close friend Schwartzkoppen, from which it can be read that Schwartzkoppen passed on intelligence information to Panizzardi.

- A letter from Panizzardi to Schwartzkoppen, in which he wrote that "ce canaille de D." (this Kanaille D.) had given him plans for a military facility in Nice so that he could forward them to Schwartzkoppen. This reference referred - as Captain Hubert Henry, who was involved in the compilation of the secret dossier, knew very well - to a cartographer from the War Ministry who had been selling plans for military facilities to the two military attachés for years and whose surname also began with D.

- Reports by the secret police officer Guénée of conversations with the Marquis de Val Carlos. They contained a text passage that, based on current research, had been added later. It was the made-up claim that "the German attachés have an officer on the general staff who keeps them extremely well informed." Guénée added this section.

Jean Sandherr , the head of the news office assigned to the Deuxième Bureau , also instructed that the secret dossier should be supplemented by a comment from du Paty, which was intended to establish a connection between these documents and Dreyfus.

The exact content of this secret dossier is not known to this day, as the list of all documents has not been found in any of the archives. Recent research has revealed evidence of the existence of around 10 documents, including letters suggesting Dreyfus' homosexuality.

Condemnation and Exile

The trial before the court martial lasted from December 19-22, 1894 and took place in camera. Court President Émilien Maurel and seven other officers sat at the court. None of these military judges was an artillery officer and was therefore in a position to classify the significance of the documents mentioned on the bordereau or to assess their accessibility. Dreyfus was defended by Edgar Demange , a Catholic known for his integrity . Demange had initially hesitated to take on the defense proposed to him; he'd promised it when he'd read the file and decided Dreyfus was innocent. Dreyfus was certain at the beginning of his trial that he would soon be acquitted. The outcome of the process was initially uncertain. According to Vincent Duclert, the judges' conviction that the defendant was guilty wavered due to his credible and logical answers to all questions. The character witnesses also vouched for Dreyfus.

However, two events turned the process, which took place in a small and sober room of the Cherche-Midi prison in Paris. When the intelligence observers had doubts about the success of their lawsuit, Major Henry secretly and illegally turned to one of the judges with a request that he be called to the stand a second time. In February and March 1894 an "honorable person" had warned the intelligence service about a traitorous officer, Henry brought up on this occasion, pointed to Dreyfus and described him as this traitor. When Dreyfus and Demange asked to name this "honorable person", Henry refused to answer on the grounds that there were secrets in an officer's head that even his cap didn't need to know. Court President Maurel stated that it was sufficient for Henry to give his word of honor as an officer that this "honorable person" had named Dreyfus. Henry then confirmed this again.

On the third day of the trial, du Paty secretly handed a sealed envelope containing the secret file to the court president during a pause in the trial. Du Paty also sent Maurel a request from Mercier to present this dossier to the other judges when the judge was deliberating the next day. The aim was to convince the court of Dreyfus' guilt - despite the poor evidence, the questionable comparison of manuscripts , the defendant's lack of motive and his pledges of innocence. This secret handover of documents, which were not brought to the attention of either the defendant or his lawyer, invalidated the military trial.

On December 22nd, 1894, Dreyfus was sentenced to demotion , life imprisonment and banishment by a unanimous vote of the military judges . The military judges had only discussed the verdict for an hour. During this consultation, Maurel and another military judge read parts of the secret dossier. Her sentence was the highest possible sentence, as the death penalty for political crimes, including treason, had been abolished since 1848. Dreyfus did not accept offers of relief from detention in the event of a confession. His request for revision was denied on December 31st. On January 5, 1895, the public demotion in the courtyard of the École Militaire followed . A hooting crowd witnessed how Dreyfus' epaulettes were torn from his uniform, his saber was broken and he was then forced to pace the ranks of the competing companies .

In January 1895, Alfred Dreyfus was moved to the fortress on the Île de Ré in the Atlantic. The French Chamber of Deputies decided on January 31, 1895, at the suggestion of War Minister Mercier, to banish Dreyfus to Devil's Island off the coast of French Guiana . The living conditions there were so harsh, not least because of the climate, that banishment to this island had become unusual since the beginning of the Third French Republic. From April 1895 until his return in 1899 Dreyfus spent his solitary confinement in a sixteen square meter stone hut with a corrugated iron roof, which was surrounded by a small courtyard enclosed with palisades. His guards, who had to watch him constantly, were forbidden to talk to him. The conditions of detention were gradually made more difficult. After rumors of an attempt to escape, he was not allowed to leave his hut for a long time. At night he was chained to his bed with iron shackles. His correspondence with the family was subject to censorship . He often received letters after a long delay. He did not find out about the developments in his case until the end of 1898.

Family reaction

In the beginning it was mainly family members of Dreyfus who tried to resume the trial, including his wife Lucie and his brother Mathieu . Mathieu Dreyfus was two years older than Alfred and had originally planned to become an officer in the French army. However, he failed the entrance exam at the École polytechnique . Instead, he and his brothers Jacques and Léon took over the management of the family business in Mulhouse . After Lucie Dreyfus had informed him by telegram of Alfred's arrest, he immediately rushed to Paris and a little later moved there with his entire family to deal exclusively with his brother's case.

Mathieu Dreyfus initially concentrated on convincing friends and as large a circle of acquaintances as possible that his brother was innocent. He was himself under constant observation by the French secret service. His letters were opened and the concierge of his Paris apartment was apparently paid for by the police. She received police agents in her entrance box. A Madame Bernard alleged to Mathieu Dreyfus that she was a spy for the French military and had contacted him because she was threatened to break her daughter's engagement with an officer under the threat of being exposed to her activity as a spy. As revenge for this extortion attempt, she wanted to provide him with documents from which the true author of the bordereau emerged. Dreyfus suspected it was a trap that was supposed to provide the police with an excuse to search his apartment and accuse him of treason. When he offered Madame Bernard to deposit the documents with a notary for a payment of 100,000 francs , she was no longer heard from.

Mathieu Dreyfus finally decided to hire the London- based detective agency Cook to help him with his research. With the help of the detective agency and the Paris correspondent of the English newspaper Daily Chronicle , the bogus news was circulated that Alfred Dreyfus had escaped from Devil's Island on September 3, 1895. Thereupon the newspaper Le Figaro took up the case again and pointed out some inconsistencies in the process. On September 8th, a travelogue appeared in Figaro , which revealed the inhumane conditions Dreyfus was exposed to. The writer Louis Begley (2009) considers this article essential because it was the first time that reading it aroused compassion for the exile in a wider circle of people .

The first Dreyfusards

Mathieu Dreyfus found initial support in the struggle to rehabilitate his brother from Major Ferdinand Forzinetti , the commandant of the military prison in which Alfred was imprisoned. Forzinetti had come to the conviction based on the behavior and the persistent testimonies of innocence of his inmate that he was actually innocent. In January 1895 Forzinetti Mathieu handed the indictment to the public prosecutor's office, which his brother had annotated on the edge of the paper. Forzinetti also recommended Mathieu Dreyfus to ask the anarchist journalist and literary critic Bernard Lazare for assistance.

Lazare had previously discussed in various publications the social and political damage that overt and covert anti-Semitism inflicted on French society. His pamphlet Une erhur judiciaire, la vérité sur l'affaire Dreyfus (A Judicial Error: The Truth About the Dreyfus Affair) appeared in late 1895 and was printed in Belgium to prevent confiscation by French authorities. Lazare criticized, among other things, the press campaign initiated by the General Staff against Dreyfus, the rule violations of the investigations carried out by du Paty and the procedural errors in the course of the process. He also contradicted Bertillon's report, according to which Dreyfus had deliberately misrepresented his handwriting, and denied the evidential value of the Ce Canaille de D. letter, stating that the German military attaché would never have compromised a useful agent in such a negligent manner.

Lazare did not stop at this script. The Jewish socialist politician and writer Léon Blum , who later became French Prime Minister several times, describes in his memoirs of the case, published in 1935, how Lazare had sought support everywhere with “admirable self-denial”, without worrying about rebukes or suspicions. One of the first to convince Lazare of Dreyfus' innocence was the moderate republican liberal MP Joseph Reinach , who came from a wealthy Jewish banking family originally based in Frankfurt . Reinach's ambitions for ministerial office had been negated by his family connections with people involved in the Panama scandal. According to the American historian Ruth Harris (2009), for this reason he mainly acted in the background in the Dreyfus Affair.

Major Picquart

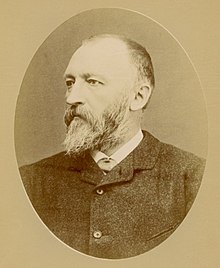

Jean Sandherr , head of the Deuxième Bureau , had to give up his post in 1895 due to a serious illness. His position took over on July 1st Lieutenant Colonel Marie-Georges Picquart , who developed into a key figure in the rehabilitation of Alfred Dreyfus. Picquart, born in Strasbourg in 1854, came from a family of officials and soldiers, had been a member of the General Staff since 1890, had already been involved in the investigation of the Bordereau in 1894 and had acted as an observer of the trial of Alfred Dreyfus. Martin P. Johnson describes him in 1999 as cultured, honorable and intelligent. He was one of the most promising officers on the General Staff.

Discovery of relief material

A few months after taking office, Picquart came to the conclusion that the German intelligence service still had contacts with a French officer: Among a large number of papers that had been stolen from the German embassy and that the intelligence service examined in March 1896, one also discovered a short message to the French major Ferdinand Walsin-Esterházy , which was signed with "C.", an abbreviation occasionally used by the German military attaché Schwartzkoppen. Because of the light blue writing paper, this piece of evidence, which is essential for the affair, is called Le petit bleu ("The little blue"). In another letter, Schwartzkoppen mentioned that his superiors were dissatisfied that they had received so little substantial information for so much money. The subsequent routine check by Major Esterhazy showed that he was heavily in debt because of his passion for gambling and his lavish lifestyle.

General staff reactions to Picquart's discovery

In August 1896 Picquart, bypassing his direct superior, Brigadier General Charles Arthur Gonse , then head of the Deuxième Bureau and convinced of Dreyfus' guilt, first informed the Chief of Staff Boisdeffre and then the new Minister of War General Jean-Baptiste Billot , who was appointed to the French Senate as republican Linker belonged to this reference to continued espionage. Assigned to continue his investigation, Picquart requested the dossiers in the Dreyfus case at the end of August and found that Esterhazy's handwriting was identical to that of the Bordereau. Picquart communicated this first orally and then in writing to both Boisdeffre and Gonse. However, Gonse in particular insisted that Picquart should treat the Esterhazy and Dreyfus cases as separate matters.

The press coverage of Dreyfus' alleged attempt to escape led to L'Éclair publishing selected contents of the secret dossier in two articles on September 10 and 14, 1896. Picquart believed that the Dreyfus family were behind these publications and that they had sufficient information to secure a retrial. According to current research, Picquart was wrong here. The reports had almost certainly been launched by an informant from the General Staff in order to encourage the public to believe that the bordereau was not the only reason for the conviction of Dreyfus. It was a risky strategy, as it made the illegal course of the process public at the same time, as the secret dossier was previously unknown to the defense lawyers. Picquart advised his superior Gonse to act as quickly as possible and arrest Esterhazy in order to avert damage to the general staff. In a private meeting on September 15, 1896, of which only Picquart's records are available, Gonse underlined that he was willing to accept the conviction of an innocent man in order to protect the reputation of Mercier and Saussier, both of whom were instrumental in the trial of Dreyfus had driven forward. Gonse also gave Picquart to understand that his silence was essential to cover up this matter, report Elke-Vera Kotowski and Julius H. Schoeps in 2005.

Major Hubert Henry's forgery

According to Begley, as Picquart suggested, the Dreyfus family responded to these indications regarding the illegality of the trial. The relatives had known since the beginning of 1895 that a secret dossier had played a role in the conviction. However, they only saw the time to act when the government did not deny the portrayal in L'Éclair . On September 18, 1896, Lucie Dreyfus asked the Chamber of Deputies to resume the trial in a letter published by several newspapers. She asked the Minister of War to make the secret dossier accessible so that the public could find out what had led to her husband's conviction. The Chamber of Deputies declined her request.

Picquart had, as ordered, kept silent about his suspicions about Esterhazy. Begley suspects that General Gonse's circle of people considered Picquart to be the weakest link in the chain of defense. The members of the General Staff involved in the intrigues must have assumed that Picquart also knew which documents in the secret dossier had been falsely linked to the Dreyfus case. This put former Secretary of War Mercier, General Boisdeffre and possibly General Gonse at risk of being charged with manipulating the court-martial process.

Gonse ordered Picquart on October 27th to go on an inspection tour of the French province. Major Henry saw Picquart's absence primarily as an opportunity to recommend himself to the General Staff as its successor. Either on October 30 or November 1, 1896, he procured a letter from the Italian military attaché Panizzardi to Schwartzkoppen, which he cut up and erroneously dated to June 14, 1894, before adding further text between the salutation and signature. Dreyfus was alleged to have sold information to the two military attachés.

Ruth Harris describes Henry's poorly glued attempt at forgery as almost grotesquely amateurish. Not only Henry's handwriting, but also the paper he used to create what is now known as faux Henry , differed significantly from the original Panizzardi on closer inspection. Nevertheless, Henry delivered this document to General Gonse on November 2nd, who, together with General Boisdeffre, shortly afterwards informed the Secretary of War of Henry's new "discovery".

Picquart's transfer to Tunisia

Shortly after this "discovery", Mathieu Dreyfus had 3,500 influential public figures sent by Lazare's writing, in which the latter denounced Dreyfus' conviction as a miscarriage of justice. On November 10, 1896, Le Matin also printed a facsimile of the Bordereau, which made it possible for every reader to compare the fonts himself. A few days later there was a debate in the Chamber of Deputies on the Dreyfus affair at the request of the MP André Castellin. In his speech, repeatedly interrupted by applause, Castellin attacked the "Jewish Syndicate", which wanted to cast doubts on the evidence, and called on the government to prosecute Lazares. War Minister Billot asserted that Dreyfus had undoubtedly committed treason and that the process had proceeded properly.

In parallel with the discussions in the Chamber of Deputies, Gonse and Henry noted some flaws in Picquart's argument. Above all, Picquart wanted to cover up the point in time when the "petit bleu" was discovered. Louis Begley writes about Picquart's motives for this attempt at veiling that his behavior can be explained by his “preference for independent work” and that he wanted to follow an “interesting lead” himself. Ruth Harris, on the other hand, argues that he acted to protect his career. He had continued the investigations against the express wishes of his superiors and then tried to conceal these facts by changing various data. Regardless of his motives, Picquart's manipulation helped weaken his credibility regarding the exoneration of Dreyfus and the allegations against Esterhazy.

Although one of the writing experts involved in the process had leaked the bordereau to Le Matin , General Gonse was convinced that Picquart was involved in the publication. Picquart was removed from his position as head of the intelligence service, initially sent to the provinces and later assigned to Tunisia . He accepted his transfer to North Africa, but feared his life in the border garrison there. In April 1897 he added to his will during a short vacation in Paris. He described his role in the affair, reiterated his suspicions about Esterhazy and underlined that he thought Dreyfus was innocent. These minutes should be given to the French President in case anything should happen to him. At the end of June he also confided in his closest friend, the lawyer Louis Leblois. At his urging, Picquart authorized him to inform a government official about the contents of the Dreyfus case record. Picquart, however, did not want to become the prosecutor of the army and forbade Leblois to make direct contact with the Dreyfus family or their lawyer or to mention the name Esterhazy.

Senator Auguste Scheurer-Kestner's and Georges Clemenceau's commitment to Dreyfus

On July 13, 1897, Leblois turned to Senator Auguste Scheurer-Kestner , who has been Vice-President of the French Senate since January 1895 , also publisher of the magazine La République Française (The French Republic) and, together with the anti-clerical radical socialist Georges Clemenceau, founder of the Union Républicaine (Republican Union ). Scheurer-Kestner, born in 1833, came from Alsace like the Dreyfus family and was considered one of the grand seigneurs of French politics. In the Second Empire he had because of his opposition to the authoritarian rule of Napoleon III. (1808–1873) served in prison.

Scheurer-Kestner initially did not doubt that the court martial had ruled lawfully, even though he felt that the exclusion of the public in the proceedings was a violation of fundamental legal principles. What he found strange was the lack of a credible motive for Dreyfus' alleged treason. However, impressed by a conversation with Mathieu Dreyfus at the beginning of 1895, he became interested in the case. His discussions with various high-ranking politicians increased his doubts: Among other things, the former French Justice Minister Ludovic Trarieux , who was also one of the founders of the League for the Defense of Human and Civil Rights , drew his attention to possible inconsistencies in the conduct of the trial. Italian Ambassador Luigi Tornielli said he believed evidence had been forged to ensure Dreyfus was convicted. After Leblois had informed him of Picquart's well-founded suspicions against Esterhazy, Scheurer-Kestner had Lucie Dreyfus informed in July 1897 that he would campaign for a reopening of the case.

His first statement to the Senate Presidium that he thought Dreyfus was innocent already attracted a lot of public attention. The support of Dreyfus by Scheurer-Kestner, who is known for his integrity, widened the circle of those who likewise expressed doubts or at least demanded that the matter be fully clarified. Scheurer-Kestner's behavior in the Dreyfus case was characterized by cautious tactics until November 1897, in which he tried to use his relationships with other politicians. In view of the increasing anti-Semitism, he feared a relapse into the religious wars of the early modern period and tried to detach Dreyfus' affiliation to Judaism from the case.

Leblois had asked Scheurer-Kestner not to go public, in order to protect Picquart, until there was further evidence unrelated to Picquart. This happened in early November 1897. First, the historian Gabriel Monod wrote in an open letter published on November 4 that, as a recognized expert in writing, he could confirm that the Bordereau was not written by Dreyfus. On November 7th, a stockbroker who happened to have acquired one of the Bordereau's facsimiles identified the manuscript as that of his client Esterhazy. As proof of this he gave Mathieu Dreyfus letters from his client.

On November 15, 1897, Scheurer-Kestner went public with an open letter in Le Temps and referred to the new facts that, in his opinion, proved Dreyfus' innocence. Almost at the same time as Scheurer-Kestner's statement, Mathieu Dreyfus accused Esterhazy of being the author of the Bordereau in an open letter to War Minister Billot. Less than a year after War Minister Billot confirmed the lawful condemnation of Dreyfus, Prime Minister Félix Jules Méline - a politician of the moderate right - was forced to assure the Chamber of Deputies that there was no Dreyfus affair. Scheurer-Kestner contradicted this declaration on December 7, 1897 in a speech before the Senate. In his very factual statements, he named the facts known to him and described the course of the process as flawed because secret documents had been transmitted to the court. Former Justice Minister Trarieux was the only senator who supported Scheurer-Kestner's arguments. He pointed out that it should not be regarded as an attack on the army if a request for rectification was submitted after serious errors were made. Prime Minister Méline, on the other hand, also stressed before the Senate that there was no Dreyfus affair.

Hannah Arendt attributes the greatest role in the battle for Dreyfus to Georges Clemenceau. He was the only one who not only fought against a “concrete” miscarriage of justice, “but always for“ abstract ”ideas such as justice , equality before the law, civil virtue, freedom of the oppressed - in short, the whole arsenal of the Jacobean Patriotism, which was as mocked and pelted with dirt back then as it was thrown into the fight forty years later. "

Esterhazy's acquittal, Picquart arrested

As early as October 1897, those involved in the intrigue began to take measures to protect Esterhazy. At first, Gonse and Henry alleged to du Paty that the Dreyfus family and their followers were plotting to blame Esterhazy. On du Paty's behalf, Henry forged a letter signed by an alleged Espérance informing Esterhazy of Picquart's investigation and warning that the “Syndicate” would accuse him of being the real traitor. At a secret meeting on October 22, 1897, du Paty and another member of the Esterhazy General Staff pledged their support. During the subsequent official meeting with General Millet, Esterhazy tried to explain the resemblance of his handwriting to that of the Bordereau with the fact that Dreyfus had imitated his handwriting. When letters to War Minister Billot and Chief of Staff Boisdeffre, in which Esterhazy asked them to defend his honor, went unanswered, Esterhazy also wrote to French President Félix Faure , a moderate republican who had spoken out against the retrial against Dreyfus. Among other things, he enclosed the so-called Espérance letter forged by Henry to prove that they were trying to set him a trap. A few days later, in a second letter to the President, Esterhazy threatened to publish a document that would be very compromising for some diplomats. Esterhazy claimed in his letter that a "veiled lady" had stolen the photographic copy of this document from Picquart, who in turn had stolen it from an embassy. Neither the presumptuous style of his letters nor the extortionate content or the alleged possession of a secret document were the reason for the government to prosecute Esterhazy, emphasize Eckhardt and Günther Fuchs in their 1994 book on the Dreyfus Affair. Instead, his improbable explanations were believed. The President asked the Secretary of War to investigate the incident, which suddenly led to Picquart being the focus of investigations for negligent use of evidence. In the first days of November 1897 Esterhazy sent Picquart two telegrams and a letter. These letters were intended to provide evidence that Picquart was involved in a plot. As Esterhazy expected, the National Security Agency intercepted both telegrams and relayed them to Henry, Gonse, and Secretary of War Billot.

On November 12th, Billot gave instructions for a secret judicial investigation against Picquart. Meanwhile, the anti-Dreyfus press suggested to a broad public that the Scheurer-Kestner campaign only served to replace a convicted Jewish officer with an innocent officer in the French army.

The preliminary investigations against Esterhazy ended on December 3, 1897. In the final report, the chief investigator General de Pellieux came to the conclusion that there was no evidence to support Dreyfus or Picquart's allegations against Esterhazy. Pellieux said the petit bleu , evidence of continued espionage and the basis of Picquart's allegations against Esterhazy, was not genuine. He recommended a committee of inquiry to clarify whether Picquart should be dismissed from the army for defamation or at least for gross breach of duty in service. General Saussier disregarded the recommendation to drop the case against Esterhazy and ordered a trial before the court martial, which took place on January 10 and 11, 1898.

distributed by F. Hamel , Altona - Hamburg ...; Stereoscopy from the Lachmund Collection

When he was questioned, Esterhazy spoke again of the "veiled lady" who had informed him of the plot against him, and claimed that Picquart had forged the "Petit bleu" and imitated his handwriting in the bordereau. The court agreed with this view. The trial ended in an acquittal for Esterhazy. Picquart, however, was arrested on January 13, 1898 for a service offense.

The question of why the French Army High Command refused to overturn the false judgment and worked so closely with Esterhazy, whom Louis Begley describes as an "amoral, obsessively lying and deceiving sociopath, " is one of the still debated subjects of the Dreyfus Affair . According to Begley, the fear of losing office and dignity played a significant role in a number of the people involved. Blum did not find this sufficiently convincing in view of the "unbelievable interweaving of intrigues and forgeries". In his memories he suspected that someone on the General Staff was involved in the transmission of information to the German embassy through Esterhazy, and attributed this role to Henry, who in his opinion, as a proven and longest-serving employee of the news office, was predestined for it. However, recent research has failed to find a basis for this point of view. Henry would also have been able to embezzle the bordereau as soon as it was discovered. Both Begley and Blum point out that very early in the affair a series of deceptions began: one cheated to cover up the previous one and lied to make the last lie believable.

Intervention and condemnation of the writer Émile Zola

J'Accuse ...!

Bernard Lazare had already tried in November 1896 to win the support of the well-known French writer Émile Zola , which he initially rejected because he did not want to interfere in political issues. According to Alain Pagès (1998), Zola had reacted with reluctance to the increasingly open manifestation of anti-Semitism. He denounced them as early as March 1896 in his article Pour les Juifs (For the Jews), but did not mention the Dreyfus case. It was only the continued commitment of Auguste Scheurer-Kestner that prompted Zola to deal more intensively with the Dreyfus affair. The first article appeared on November 15, 1897 in the newspaper Le Figaro and dealt with Scheurer-Kestner's efforts to clear up the miscarriage of justice. Another article, Le Syndicat (The Syndicate) , followed on December 1 , which took up the repeated accusation that a Jewish syndicate was trying to buy an acquittal from Alfred Dreyfus. Zola dismissed this as an old wives' tale and urged his readers to see the Dreyfus family not as part of mysterious and diabolical forces, but as French citizens who would do everything in their power to restore the rights of their innocent loved ones. On December 5, in the article Le Procès-verbal (inventory) , Zola expressed his hope that a military trial against Esterhazy would reconcile the nation and put an end to the barbaric anti-Semitism that is throwing France back a thousand years.

Shortly afterwards, Le Figaro ended his collaboration with Zola after anti-Dreyfusards and right-wing extremist nationalists had called for a subscription boycott of the newspaper. Now without a newspaper ready to print his articles, Zola published his next two articles as brochures on December 13 and 14, 1897, but they sold poorly because of their high price of 50 centimes each. In Lettre à la Jeunesse (Letter to the Young), he addressed the right-wing students who had organized a violent demonstration against Dreyfus in the Latin Quarter and urged them to return to the French traditions of generosity and justice. On January 6, 1898, in Lettre à la France (Letter to France), he attacked the part of the press that got its readers in the mood for Esterhazy being washed clean.

For his next publication, Zola turned to the literary magazine L'Aurore (The Sunrise), newly founded by Georges Clemenceau : On January 13, 1898, his open letter to President Félix Faure J'accuse appeared on the front page ...! (I'm accusing ...!) , In which he again denounced Esterházy's acquittal.

Zola rhetorically took on the role of a public prosecutor in his text . He accused du Paty, Mercier, Billot, Gonse and Boisdeffre of being masterminds of a plot, accused the "dirty press" of anti-Semitic propaganda and again accused Esterhazy of being the real traitor. The author also raised the question, which was decisive for Pagès and prophetic for the further course of the affair, of the extent to which these military judges were still able to give an independent judgment. A conviction of Esterhazy would have been a judgment on the court martial, which Dreyfus had pronounced guilty of high treason. Each of the military judges ruling on Esterhazy knew that their minister of war had affirmed, to the applause of the MPs, that Dreyfus had been rightly convicted. Zola accused the first court martial

"[...] to have violated the right by convicting a defendant on the basis of an undisclosed piece of evidence, and I am indicting the Second Court Martial of having covered this unlawfulness on orders and in doing so committed the criminal offense of knowingly acquitting a guilty party . "

Within a few hours, more than 200,000 copies of the newspaper had been sold. Immediately after the publication of the article there were violent riots by the forces directed against Dreyfus, which were particularly violent in Algeria , where a relatively large number of Sephardic Jews lived. In Paris, Jewish shops, merchants and well-known Dreyfusards were the targets of attacks. On Place Blanche in Montmartre , Ruth Harris reports, a gathering - made up of artists, students and workers - burned a rag doll with a sign with the name of Mathieu Dreyfus on it. Posters posted all over Paris called for anti-Dreyfusard alliances. Jules Guérin , the founder and leader of the Antisemitic League of France , stirred up the crowds even further at a meeting, whereupon violent crowds gathered in front of Mathieu Dreyfus 'house as well as that of Lucie Dreyfus' parents. The riots took several days to end; they escalated again when the trial against Zola came.

To this day, Zola's open letter is considered one of the greatest journalistic sensations of the 19th century and was the turning point in the Dreyfus affair, judges Ruth Harris. According to Begley, the courage he demonstrated with this publication cannot be rated highly enough. He was at the height of his literary success and his admission to the Académie française seemed only a matter of time before the article appeared and the scandal that followed. Zola wanted to provoke a trial with his militant text, since Dreyfus was initially denied further proceedings before the military jurisdiction. He was hoping for an acquittal by civil justice, which would also have represented an acknowledgment of the innocence of the officer Alfred Dreyfus. However, he also risked being arrested and sentenced himself.

Two days later, on January 15, 1898, Le Temps published a petition calling for the misjudgment to be revised. In addition to Émile Zola, the writer Anatole France , the director of the Institut Pasteur Émile Duclaux, the historian Daniel Halévy , the poet and literary critic Fernand Gregh , the anarchist journalist and art critic Félix Fénéon , the writer Marcel Proust , the socialist intellectual and one had signed the founder of the League for the Defense of Civil and Human Rights Lucien Herr , the Germanist Charles Andler , the ancient historian and politician Victor Bérard , the sociologist and economist François Simiand , the syndicalist and social philosopher Georges Sorel , the painter Claude Monet , the writer Jules Renard , the sociologist Émile Durkheim and the historian Gabriel Monod .

Condemnation and Exile

On the day of publication, conservative parliamentarians and the general staff called for action against Zola. On January 18, 1898, the Council of Ministers decided that the Minister of War should file a defamation suit against Zola and Alexandre Perrenx, the managing directors of L'Aurore . Contrary to what Zola expected, the prosecution focused their accusations on the passage where Zola had accused the court-martial of acquitting Esterhazy on orders. The charge against Zola was thus unrelated to the conviction of Dreyfus.

The process took two weeks. On each of the trial days, nationalist demonstrators waited outside the gates of the Palace of Justice for Zola's appearance, only to greet him, as Pagès drastically describes, with hoots, stones and death threats. In the courtroom, his two lawyers, Fernand Labori , a well-known lawyer, journalist, politician and Dreyfusard from the very beginning, and Albert Clemenceau, Georges Clemenceau's brother, succeeded in repeatedly eliciting statements from the witnesses about the Dreyfus affair through their skillful questioning Presiding judges constantly tried to limit their questions to matters of the prosecution. Cornered, General Pellieux brought up another document allegedly clearly proving Dreyfus's guilt, quoting the wording of this faux Henry . When Labori asked that the document be presented to the court, General Gonse intervened, who, unlike Pellieux, was aware that it was one of the forgeries in the secret file. He confirmed the existence of the document, but claimed it could not be made public. The court then had Chief of Staff Boisdeffre appear as a witness. Boisdeffre confirmed Pellieux's statements and then turned to the court as a warning:

“You are the judgment, you are the nation; if the nation has no confidence in the leaders of its army, in the men who are responsible for national defense, then those men are ready to leave their heavy duty to others, you just have to tell. This is my last word."

According to Léon Blum, the trial made it clear that Zola's allegations were true. However, Boisdeffre's words demanding a decision between the army and Zola and the Dreyfusards had made a strong impression in public and in the courtroom. On February 23, 1898, both defendants were fined 3,000 francs - more than one and a half times the annual salary of a lieutenant - Zola was sentenced to an additional year in prison and L'Aurore's manager , Perrenx, to four months. Prime Minister Méline described the Zola and Dreyfus cases as closed the next day in the Chamber of Deputies.

Two days later, Picquart was dishonorably discharged from the army. However, the Supreme Court of Appeal initially overturned the judgment against Zola because of a procedural error. On July 18, 1898, Zola was found guilty a second time. Labori and Clemenceau then advised him to leave France immediately, as that would mean that the judgment could not be served and enforced. Zola left for London that same day.

Hubert Henry's confession, suicide and reaction

In the parliamentary elections in May 1898, the Méline government lost its support and resigned on June 15. On June 28, the leader of the radical republicans Henri Brisson formed a new government, Godefroy Cavaignac succeeded Billot as Minister of War for a short time. Cavaignac was one of the group of people who still assumed a lawful conviction of Dreyfus'. In response to a request from an MP about the Dreyfus affair, he made a long speech and cited Le faux henry , the Ce canaille de D. letter and another letter from Panizzardi as evidence of the lawful judgment .

This time it was the socialist MP Jean Jaurès who challenged the war minister in an open letter and announced that he would refute Cavaignac's argument point by point. He did so in a series of articles that appeared in La Petite République in August and September 1898 . The central point of his argument was the claim that Le faux henry was a forgery fabricated by the General Staff. This led to a re-examination of the evidence, some of which was done by lamplight. Captain Cuignet noticed the two different types of paper that made up the document. Like General Roget, he assumed it was indeed a forgery, as Picquart had previously claimed.

Cavaignac was informed of this on August 14, 1898, but it was not until August 30 that he questioned Hubert Henry in the presence of Generals Boisdeffre and Gonse. Henry first tried to deny it, but then, under the pressure of questioning, admitted that he had forged the letter. He was arrested and taken to the Mont Valérien military prison. In a brief statement, the government announced that the forgery of the document had been discovered. On August 31, Henry committed suicide by slitting his throat with his razor. Then all anti-Semitic newspapers said that Henry had been paid by the Jews to testify.

Boisdeffre resigned after Henry's death, Gonse was transferred to active service by the General Staff and du Paty retired. Esterhazy, who had meanwhile fled to Belgium, admitted in press interviews that he had written the bordereau. On September 3, 1898, Lucie Dreyfus filed another appeal for a revision, and the politically neutral press now also called for the trial to be restarted. On September 5, Cavaignac resigned as Minister of War. His successor Émile Auguste Zurlinden stayed in office for only eight days. He resigned after the Supreme Court of Appeal decided to reopen the case so as not to have to initiate the appeal proceedings in Dreyfus' favor. The new Minister of War Charles Chanoine appointed Zurlinden military governor of Paris. Its first action was to bring a lawsuit against Picquart, who had been in custody since July 15, 1898. Minister of War Chanoine tried - like his predecessors - to prevent a revision procedure for Alfred Dreyfus. As a result, on November 1, 1898, the entire cabinet resigned.

The Dreyfusards' expectation that Henry's admission of forgery and his suicide would result in a widespread change of public opinion was not fulfilled. Far -right Charles Maurras called the forgery and suicide of Henry a heroic sacrifice in the service of a higher cause. Henry had a remarkable military career, in the course of which he had been wounded several times. According to Maurras, this lifetime achievement was only offset by a forgery and a lie, for which Henry, as a real soldier, had paid with his life. The nationalist press willingly took up this heroization of Henry, and Édouard Drumont called Henry's suicide "admirable" in La Libre Parole . According to the nationalist and anti-Semitic press, however, Picquart was the “true” forger, against whose fabrications and lies Henry's forgery was a harmless transgression of boundaries.

On Reinach's series of articles in Le Siècle , which thematized the connection between Esterhazy and Henry, the right-wing press replied that this was character assassination against a deceased who only had his widow and four-year-old child as defense lawyers. Drumont called for a fundraiser to enable Berthe Henry to sue Reinach for defamation. By January 15, 1899, more than 25,000 people donated 131,000 francs. According to Begley, the donors included 3,000 officers and 28 retired generals, aristocrats disempowered by the revolution, including seven dukes and duchesses and almost five hundred marquis, counts, viscounts and barons. Many of the donations, Ruth Harris reports, were accompanied by hateful letters to Alfred Dreyfus's defense lawyers, published by Drumont.

Hearing before the criminal division of the Supreme Court of Appeal

After the Chamber of Deputies refused to grant Lucie Dreyfus' motion to retrial, the only appeal left was a case before the Supreme Court . A defendant himself had no right to apply for a revision here; the government alone was entitled to do so. The Brisson cabinet was more open to such a review process than the previous governments and authorized the Minister of Justice with six to four ministerial votes in September 1898 to initiate the review process. While the political discussion was increasingly dominated by the Faschoda crisis and thus the competition between France and Great Britain in the colonization of Africa, the criminal chamber of the Supreme Court of Appeal had been meeting since November of the same year. In the course of the trial, the right-wing newspapers La Libre Parole and L'Intransigeant (The Uncompromising) attacked the judges and accused them of being paid by the “Jewish Syndicate” and the German Reich .

On November 1, 1898, the progressive Charles Dupuy took the place of Brisson. At the beginning of the affair in 1894 he had still covered Mercier's machinations. Now he announced that he would follow the orders of the court of appeal. In doing so, he blocked those who wanted to prevent the appeal and declare the court incapable of jurisdiction. During a debate in the chamber on December 5, 1898 about the transfer of the secret dossier to the court, tension rose. The insults, insults and other attacks on the part of the nationalists culminated in threats to instigate a riot. Paul Déroulède , chauvinist and anti-Semite, declared: "S'il faut faire la guerre civile, nous la ferons." (If we have to unleash a civil war, we will.)

The former war ministers Mercier, Cavaignac, Billot, Chanoine and Zurlinden were heard as witnesses. Mercier claimed that Dreyfus confessed to officer Lebrun-Renault in 1894, but otherwise refused to answer any questions. According to Cavaignac, Dreyfus and Esterhazy had worked together. General Roget shared this view and justified this by saying that Esterhazy had not been able to obtain the information mentioned on the bordereau in any other way.

Four artillery officers contradicted this position on January 16 and 19, 1899. In their opinion, the inaccuracy of the technical terms mentioned in the Bordereau was evidence that the author was not an artilleryman. They also pointed out that the information given according to the bordereau might as well have come from the military press of the time.

A total of ten writing experts were questioned. Four of them testified for Dreyfus, a fifth remained cautious and confined himself to the remark that there were two manuscripts that resembled the one on the bordereau. Alphonse Bertillon, whose handwriting comparison had already been decisive in the 1894 trial, again took the view that Dreyfus had deliberately misrepresented his handwriting. When asked about his role in the trial before the 1894 trial, he stated that Dreyfus' reaction at the time was an indirect admission and that he was therefore sticking to his "self-forgery theory".

With the approval of the government, the diplomat, historian and essayist Maurice Paléologue also testified in front of the Chamber and presented the documents on the Dreyfus case that were kept in the Foreign Ministry. Among other things, he disclosed that the version of Panizzardi's telegram submitted by the War Ministry, which Panizzardi had sent to the Italian army headquarters at the beginning of 1894, was forged. There is only one official version, namely that deciphered by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs . This version exonerated Dreyfus.

Before the criminal division could reach a decision, however, the president of the civil division, Jules Quesnay de Beaurepaire , alleged bias against the judges in the criminal division. A few days later on January 8, 1899, he resigned his office and began a violent insulting press campaign in the Écho de Paris against his colleagues Louis Loew, Alphonse Baud and Marius Dumas, all of whom were responsible for the revision of the Dreyfus trial. He accused the chairman of the criminal chamber, the Protestant of Alsatian descent Louis Loew, of adopting an overly benevolent attitude towards Picquart. The Chamber of Deputies therefore opened an investigation. The investigative commission cleared the judges of the criminal chamber of all allegations and stated that their integrity and righteousness were beyond doubt.

Shortly thereafter, Prime Minister Charles Dupuy introduced a draft law in the cabinet, according to which all current appeals should be submitted for review to the joint chambers of the appellate court. Despite fierce opposition from individual ministers, Whyte said in 2005, the cabinet supported Dupuy in its majority and presented this bill to the House of Representatives, which was passed on February 10, 1899 with 324 votes to 207.

Attempted coup and trial in the Joint Chamber of the Supreme Court of Appeal

Before the Joint Chamber of the Supreme Court of Appeal could re-examine the Dreyfus case, Paul Déroulède , the founder of the chauvinist and anti-parliamentary Ligue des Patriotes, attempted a coup on February 23, 1899 after the state funeral of President Faure . Déroulède was one of those people who saw the events of the Dreyfus Affair primarily as an attack on the honor of the French army. He was counting on the support of the army for his coup d'état. General de Pellieux, who commanded the main escort at the funeral of Faure, was to meet Déroulèdes troops on his return from the funeral near the Place de la Nation , then deviate from the planned route as agreed and march towards the Elysée Palace . However, Pellieux broke his word at the last moment and asked the Military Governor Zurlinden to put him in command of a smaller escort. General Roget, who took his place, arrested Déroulède. Déroulède was sentenced to ten years in exile; after six years of exile in Spain he was pardoned.

On March 27, 1899, the Joint Chamber began examining the secret dossier. Like the judges of the criminal division before, she came to the conclusion that the dossier did not contain any documents incriminating Dreyfus. The court also questioned Captain Freystaetter, who was one of the judging officers during the court martial. He confirmed that the so-called Ce canaille de D. letter had been secretly leaked to the judges during the trial, and also admitted that Henry's theatrical witness appearance had led him to convict Dreyfus. The Panizzardi telegram to the Italian headquarters again played a role in the negotiation. In order to ensure that the foreign minister's deciphered version was the correct one, the court ordered representatives from the war and foreign ministries to jointly decipher the original telegram a second time. The version now created corresponded to that of the Foreign Ministry, according to which there had been no contact between Panizzardi and Dreyfus. On June 3, 1899, the Supreme Court of Appeal declared the judgment of the court martial of 1894 invalid and stipulated that Dreyfus had to face another court martial in Rennes .

Second trial of Dreyfus, new conviction

Due to the heavily censored correspondence, Alfred Dreyfus knew nothing about developments in France until November 1898. In mid-November he received the summary of his case, which the lawyer Jean-Pierre Manau had presented to the Supreme Court of Appeal. Only then did he find out about Henry's suicide and his brother Mathieu's accusation against Esterhazy as a traitor. Shortly afterwards, his detention conditions were eased; a little later he was brought before judges at the Cayenne Court of Appeal . He denied having made a confession to Lebrun-Renault in January 1895 .

Strictly guarded, Alfred Dreyfus began his return journey to France a week after the Supreme Court of Appeal overturned his judgment. From July 1, 1899, he was held in the Rennes military prison, where he was allowed to see his wife and brother again for the first time. After nearly five years of solitary confinement - his guards were strictly forbidden to talk to him - Dreyfus was initially barely able to speak. Due to inadequate nutrition, he had also lost several teeth, which made it difficult for him to speak. He was very emaciated and at first could hardly eat any solid food. Mathieu Dreyfus in particular was concerned about whether his brother would survive the coming military trial.

Numerous Dreyfusards and anti-Dreyfusards as well as many journalists from the national and international press came to Rennes for the revision process. The former Minister of War, General Auguste Mercier, again appeared as an incriminating witness, while the former President Jean Casimir-Perier testified for Dreyfus.

Lucie Dreyfus had found accommodation near the military prison, and although she tried to avoid any attention, according to Ruth Harris, 300 people gathered there when she arrived. Lucie Dreyfus, who has always been wearing mourning clothes since her husband's arrest , was a figure well known to the public despite her best efforts to remain in the background. In the Dreyfus-friendly press she had become the symbol of a self-sacrificing and loyal wife. The now physical presence of Alfred Dreyfus, who had previously only been an abstraction for most, required an emotional adjustment from everyone present, according to Ruth Harris. It did not matter whether they had previously venerated Dreyfus as a martyr or reviled them as "Judas".

The right-wing novelist , journalist and politician Maurice Barrès , a staunch anti-Dreyfusard, was deeply shocked when he saw Dreyfus in person for the first time during the trial:

“How young he seemed to me at first, this poor little man who, laden with so much that was said and written about him, came forward with incredibly fast strides. At that moment we all felt nothing but this small wave of pain entering the room. A miserable scrap of human being dragged into the bright light. "

Dressed in his old uniform, which was stuffed with cotton wool to hide his emaciated body, on skeletal legs that could hardly carry him, and with his monotonous, metallic, soundless voice, he did not fit into the image of the tragic hero of many Dreyfusards. Léon Blum described Dreyfus as a serious, humble man who had nothing heroic but a silent, unshakable courage . Louis Begley also points out, however, that Dreyfus, with his stiff, mask-like face and his emotionless voice, was a somewhat engaging defendant in court.

His lawyers Demange and Labori disagreed in their litigation. They made several mistakes during the trial. Although the Supreme Court of Appeal had already clarified that Dreyfus had never confessed to the treason and that the Panizzardi letters had no evidential value, the two attorneys accepted, for example, that the prosecution re-presented this evidence to the military court.

There was also an attack on Labori during the trial . He was shot in the back on the street in Rennes on August 14, and the assassin was never caught. The lawyer was able to resume his defense after a week, but the attack unsettled him permanently, writes Ruth Harris. The main problem facing the defense was that the judges were officers who were exposed to the influence and pressure of the top management of the army. You should, Begley said, condemn Dreyfus again.

On September 9, 1899, Dreyfus was found guilty of treason a second time by five to two judges' votes. However, attenuating circumstances were taken into account and his sentence was reduced to ten years.

Pardon and dispute for the supporters

Mathieu Dreyfus was convinced that his brother would not survive another six months in prison. He turned to Joseph Reinach, who saw the only solution as a pardon. Reinach talked about it with his friend, the new Prime Minister Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau , and met both the progressive moderate Republican and the new War Minister Garcon de Galliffet to accommodate. Both politicians thought a pardon was urgently needed. There was, however, a legal and a political hurdle.

The legal hurdle resulted from Demange's objection, with which he had prevented the Rennes judgment from becoming final. According to the law, a penalty could only be waived after a final judgment. Alfred Dreyfus therefore had to withdraw his objection, which part of the French public would interpret as an acceptance of the condemnation. Cabinet member Alexandre Millerand urged this step because the committed Dreyfusard considered the objection to be risky: If the review commission of the Supreme Court of Appeal found a formal error in the conduct of the proceedings, Dreyfus would be brought before a military court again. The risk of a new guilty verdict was high and there was a possibility that this military tribunal might be less lenient. Reinach, Jaurès and finally, reluctantly, Georges Clemenceau therefore advised Mathieu Dreyfus to suggest that his brother withdraw the objection. Alfred Dreyfus followed this advice.

However, President Émile Loubet , who had previously been neutral in the affair, initially refused to sign a pardon, as this could also be understood as a criticism of the army and the military court proceedings. War Minister Galliffet finally suggested to Loubet that the pardon should be presented as an act of humanity and that Dreyfus should be referred to in the grounds of the decree. On September 19, 1899 Dreyfus was finally pardoned.

The withdrawal of the objection and the subsequent pardon ultimately led to a split within the Dreyfusards. Many had made personal sacrifices as they were professionally and socially disadvantaged because of their efforts to rehabilitate Dreyfus, argues Begley.

Their mission was not only about Dreyfus, but also about fundamental questions of the understanding of law and the role of the army in the state. From this purely constitutional point of view, an objection to the Rennes judgment was an imperative. Two measures by Waldeck-Rousseau and Galliffet exacerbated the division within the Dreyfusards. Both politicians were convinced of Dreyfus' innocence, but they were keen to end the affair in a way that would save the face of the army. Galliffet issued a daily order two days after the pardon , which was read out in every company. There it said:

"The case is closed. The military judges, accompanied by the respect of all, pronounced their guilty verdict completely independently. We bow to your decision without reservation. We also bow to the deep sympathy that guided the President of the Republic. "

On November 19, 1899, Waldeck-Rousseau submitted an amnesty law to the Senate , under which all crimes committed in connection with the affair should fall. The only exception was the crime for which Dreyfus had been convicted in Rennes. This left him the opportunity to achieve complete rehabilitation through a revision procedure. The Amnesty Act, which came into force in December 1900, ended many pending proceedings, such as those against Picquart and Zola. However, it also prevented legal action against people like Mercier, Boisdeffre, Gonse and du Paty, who were involved in the intrigue. Alfred Dreyfus and Major Picquart were among those who protested sharply against this amnesty law. Dreyfus was dependent on bringing new facts to the Supreme Court of Appeals so that it could verify the validity of the Rennes judgment. It was likely that trials of those involved in the scheme would provide this evidence.

Picquart had always dealt with the rule of law in the Dreyfus case. For this he had accepted the loss of office and imprisonment. He was eventually discharged from the army. While the amnesty law was being discussed, Picquart appealed his release. The chances of success were high. In response to the amnesty law, Picquart withdrew his appeal, stating that he would not accept anything from a government that dares not bring criminals to justice in high positions.

Rehabilitation

From 1900 to 1902 the Dreyfus Affair only played a subordinate role in public discussion. This was due to the fact that Waldeck-Rousseau had, among other things, the dissolution of the Catholic Order of Assumptionists in France, which through its newspaper La croix (The Cross) had been one of the most decisive anti-Semitic voices during the Dreyfus affair. Arendt complains that only one of the Dreyfusards opposed this ban, namely Bernard Lazare .

In the spring of 1902, Waldeck-Rousseau led the left bloc to victory again in the elections to the National Assembly, but shortly afterwards resigned from all political offices due to a serious illness. On June 7, he was succeeded by Émile Combes in office as Prime Minister, the new Minister of War was Louis André . Both were staunch opponents of clericalism and fought for republican ideals. The Dreyfus, Jaurès, Trarieux, Clemenceau brothers and the Dreyfus lawyers came to the conclusion that under this government there was a good chance they would really end the Dreyfus affair with an appeal.

The prelude to the appeal proceedings was again a speech by Jaurès before the Chamber of Deputies, in which he once again provided evidence of Dreyfus' innocence and called for an investigation into the falsifications of the General Staff. According to Begley, there were turbulent scenes during the session. MPs shouted at each other and verbally attacked each other. The shift in the balance of power in the Chamber of Deputies in favor of the Republican bloc achieved with the elections of 1902 meant that Jaurès' request to have General André re-investigated found a parliamentary majority.

On behalf of Andrés, his adjutant and the ministry's chief attorney examined the bulk of the files that had been put together for the Rennes trial. In doing so, they discovered that the dossier, which had been expanded to more than 1,000 documents since 1894 (Martin P. Johnson, 1999), contained several other bogus evidence in addition to the faux Henry . The investigation file was handed over to the Minister of Justice in November 1903 by decision of the Cabinet; At the same time, Alfred Dreyfus was given to understand that an application for judicial review would be promising. The subsequent proceedings before the Supreme Court of Appeals dragged on for an excruciatingly long time; a verdict was finally reached on July 11, 1906. The civil court unanimously overturned the Rennes military ruling and decided against referral to another court with 31 votes to 18 . This was justified by the fact that there was no criminal act on the part of the accused which could lead to conviction in a new trial. Dreyfus was thus clearly and irrevocably declared innocent. The court ruled that the judgment should be published in the state daily newspaper, Journal officiel de la République française, and in 55 other newspapers to be selected by Dreyfus.

On July 13, 1906, Dreyfus was appointed major and Picquart brigadier general. The two decrees passed by the French legislature took into account the years of service that Picquart had spent in prison for unlawful prosecution, but not that of Dreyfus. On July 20, Dreyfus was awarded the insignia of a Knight of the Legion of Honor. On October 15 of the same year he returned to active service as a major in an artillery unit at Fort Vincennes. His comrades of the same age were, however, superior to him in the hierarchy of the army, which, in Begley's opinion, made the service so untenable that he retired from the army after a year.

Dreyfus never asked for compensation from the state or anyone involved. Duclert wrote in his biography in 2006 that he only wanted to establish his innocence.

Further career of the main actors

Auguste Scheurer-Kestner died in 1899 on the day Dreyfus was pardoned. The French Senate honored him and Ludovic Trarieux, who had also died in the meantime, in 1906 with the decision to display their busts in the Senate's gallery of honor. Émile Zola also did not see the complete rehabilitation of Alfred Dreyfus; he died in his Paris apartment in 1902 of carbon monoxide poisoning due to a blockage in his fireplace.

Alfred Dreyfus attended the funeral with his brother, despite the initial concern of Zola's widow that his presence would lead to riots, and the night before was one of the people who kept the wake at Zola's coffin. Dreyfus, his wife Lucie and his brother Mathieu were also present when Zola's remains were solemnly transferred to the Panthéon on June 4, 1908 . During the celebrations, the extreme right-wing journalist Louis-Anthelme Grégori carried out an assassination attempt on Dreyfus. The two bullets that Grégori fired only touched Dreyfus lightly on the arm. He acted on behalf of Action française to disrupt the ceremony. According to Duclert, he wanted to meet both “traitors” Zola and Dreyfus. Ruth Harris describes the subsequent acquittal of Grégoris by a Paris court as an indication of how strongly the Dreyfus affair still shaped French society.