Alphonse Bertillon

Alphonse Bertillon (born April 22, 1853 in Paris , † February 13, 1914 in Münsterlingen , Switzerland ) was a French criminalist and anthropologist . The anthropometric system he developed for personal identification was later named Bertillonage in his honor .

Live and act

Alphonse Bertillon was born on April 22, 1853 as the second son of the then well-known physician, statistician and Vice-President of the Anthropological Society of Paris, Dr. Louis-Adolphe Bertillon was born in Paris . His grandfather was the naturalist and mathematician Achille Guillard .

Bertillon spent his youth in Paris. He had to drop out of school prematurely due to poor performance and behavior. Bertillon was considered a choleric and pedant . In addition, he was often ill and suffered from severe migraines . As a result of these circumstances, he became a loner at an early age and was poor in contact and closed off throughout his life.

Thanks to the intercession of his widely respected father, he was employed as an assistant clerk at the Paris Police Prefecture in March 1879 . In this function, he mainly had to transfer descriptions of criminals who had committed criminal offenses onto index cards . The usefulness of these index cards was in many ways dubious. Bertillon remembered his father's work and came across the anthropological research of Adolphe Quetelet . In the course of his investigations, he came to the conclusion that there are no two people with the same body size.

Based on this knowledge, Bertillon developed the first closed system for personal identification between 1879 and 1880 and thus made a decisive contribution to scientific criminalistics .

Bertillon carried out his first attempts on remand prisoners brought in by the Paris police. He recorded the measurement results on index cards. More than once this work earned him ridicule from his colleagues in the prefecture. The then police prefect of Paris first put Bertillon's report on file and then even threatened to dismiss him without notice if he should bother him again with his ideas. Bertillon's father was no less indignant at first, but then recognized the potential of his son's work. With his support and after a change at the head of the prefecture, Bertillon was allowed to continue his work.

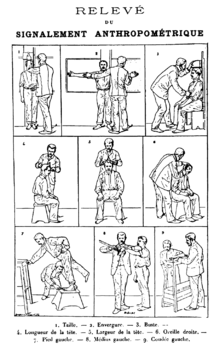

Bertillon had found that the more the body measurements increased, the more accurate the identification. When 11 body measurements were taken, the risk of confusion was 4,191,304 to 1. He considered this sufficient and therefore suggested the use of the following 11 body measurements: body length, arm span, seat height, head length, head width, length of the right ear, width of the right one Ear (later zygomatic width), length of the left foot, length of the left middle and little finger and length of the left forearm.

The first major experiment began in November 1882. Bertillon was allowed to test his method for 3 months. For this purpose he was given his own room and two employees. In February 1883 he had already created 1,800 index cards. These were not sorted alphabetically, but according to the corresponding body measurements. The test run ended in February 1883. Shortly before that, he succeeded in what his critics considered impossible: the identification of a recidivist offender based on his body measurements. The trial period was then extended and Bertillon was assigned additional staff. By the end of 1882 he was able to prove 49 identifications. On February 1, 1888, Bertillon was promoted to head of the police identification service.

Although the Bertillon system was then used in many other countries, it was subject to constant criticism from the criminal police. For most investigators it was too complex and the large amount of data could only be used with the help of the appropriate index cards. Bertillon then developed a wanted book called DKV with the descriptions of wanted or expelled people.

In 1893 Bertillon was awarded the Legion of Honor red ribbon in recognition of his services .

Later, the anthropometric measurements were supplemented by two-part photographs of the perpetrators and, against Bertillon's resistance, finally by fingerprints. Bertillon was an opponent of dactyloscopy , which he believed to be imprecise. In spite of this, he himself succeeded in identifying a murderer in Europe for the first time in 1902 using a fingerprint. However, the success could not change Bertillon, who continued to reject dactyloscopy and was reluctant to talk about this case in the following years.

On the occasion of the world exhibition in Liège , the Paris prefect of police announced that 12,614 recidivists have so far been identified in Paris using the system developed by Bertillon.

The theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre in 1911 finally revealed the Bertillonage's flaws . The thief Vincenzo Peruggia , who was only arrested in 1913, had left his fingerprints on both a pane of glass and a door handle. These had been registered since 1909, but could not be found in the thousands of index boxes sorted by body size. With the discovery of this weak point, the end of Bertillon's system was sealed.

Alphonse Bertillon fell seriously ill in 1913 and died on February 13, 1914 in Münsterlingen , Switzerland . In the last months of his life he was almost completely blind. The award of the rosette to the ribbon of the Legion of Honor failed because of his stubborn demeanor. Bertillon was unwilling to admit his own error in the written report in the Dreyfus affair.

Shortly after his death, dactyloscopy replaced Bertillonage in France , as its errors such as excessive complexity, the possibility of mix-ups and the dependence on the accuracy of the measurements became more and more obvious. However, some elements of his system have been preserved in the criminal investigation service to this day, such as the portrait and profile shots after an arrest ("mug shot"). Both Bertillonage and dactyloscopy are each a biometric recognition process .

Role in the Dreyfus affair

In the high treason trial against the Jewish officer Alfred Dreyfus , Bertillon acted - without relevant experience - as a graphological expert in order to prove that Dreyfus was the author of the secret correspondence with the German embassy in Paris. Regarding the differences between Dreyfus' handwriting and that on the question Bordereau he insisted both in the first trial in 1894 and in the appeal trial in 1899 that Dreyfus had forged his own handwriting - calling them disguised in such a way as would someone who imitates his (Dreyfus') handwriting.

As doubts about his expertise and the logic of his statements arose, he tried to save his position by claiming that the document had to be from Dreyfus precisely because it could not be proven that it was from him. The lack of traceability suggests a perfectly thought-out defense system, which in turn proves the perfect guilt.

Even after Dreyfus' complete rehabilitation he refused to admit a mistake; not even when the actual author, Ferdinand Walsin-Esterházy , admitted his authorship in press interviews. Shortly before his death, Bertillon renounced an order because its award was tied to the condition that he admit his error in the Dreyfus affair.

Although Bertillon's reputation suffered considerably as a result of this affair, his grave error had little professional consequence. He remained director of the identification service. Only control of the graphological department was withdrawn from him, and he was not allowed to realize his plans for a forensic laboratory (the first of its kind was later set up by his student Edmond Locard ).

literature

- Henry Rhodes: Alphonse Bertillon: Father of Scientific Detection . Abelard-Schuman, New York, 1956

- Gerhard Feix : The big ear of Paris - cases of the Sûrete . Verlag Das Neue Berlin, Berlin, 1975, pp. 146–194

- Dietmar Kammerer: »What is the face of crime? The ›certain individuality‹ of Alphonse Bertillon's ›crime photography‹ «, in: Nils Zurawski (ed.): Sicherheitsdiskurse. Fear, control and security in a ›dangerous‹ world , Frankfurt / Main: Peter Lang, 2007, 27–38.

- Nicolas Quinche: Crime, Science et Identité. Anthology of the text fondateurs de la criminalistique européenne (1860-1930). Genève: Slatkine, 2006, 368p., Passim .

- Allan Sekula: The body and the archive , in: Herta Wolf (ed.): Discourses of photography. Photo criticism at the end of the photographic age , Frankfurt / Main, 2003, pp. 269–334.

Web links

- Sabine Mann: February 13th, 1914 - Anniversary of the death of Alphonse Bertillon WDR ZeitZeichen on February 13th, 2014. (Podcast)

Individual evidence

- ^ Laurent Rollet: Autour de l'affaire Dreyfus - Henri Poincaré et l'action politique . Séminaire de l'Institut de Recherche sur les Enjeux et les Fondements des Sciences et des Techniques, Strasbourg 1997, pp. 6-13. Retrieved on May 4, 2014 (PDF, 354 kB)

- ↑ Jim Fisher: Alphonse Bertillon. The Father of Criminal Identification . Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- ^ GW Steevens: The Tragedy of Dreyfus . Harper & Brothers 1899, p. 220 ff.

- ^ GW Steevens: The Tragedy of Dreyfus . Harper & Brothers 1899, p. 224

- ↑ a b Sabine Mann: ZeitZeichen: February 13, 1914 - The anniversary of the death of the criminalist Alphonse Bertillon ( Memento from May 5, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (MP3 audio file, 13 MB)

- ↑ Criminocorpus: Alphonse Bertillon and the Identification of Persons (1880-1914) . ( Memento of 4 May 2014 Internet Archive () english )

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bertillon, Alphonse |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French criminalist and anthropologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 22, 1853 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Paris |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 13, 1914 |

| Place of death | Münsterlingen , Switzerland |