French Revolution

The French Revolution from 1789 to 1799 is one of the most momentous events in modern European history . The abolition of the feudal - absolutist corporate state as well as the propagation and implementation of fundamental values and ideas of the Enlightenment as goals of the French Revolution - this applies in particular to human rights - were among the causes of far-reaching power and socio-political changes throughout Europe and have decisively influenced the modern understanding of democracy. Second among the Atlantic RevolutionsIn turn, she received orienting impulses from the American struggle for independence . Today's French Republic as a liberal-democratic constitutional state with a western character bases its self-image directly on the achievements of the French Revolution.

The revolutionary transformation and the development of French society into a nation was a process in which three phases can be distinguished:

- The first phase (1789–1791) was characterized by the struggle for civil liberties and the creation of a constitutional monarchy .

- The second phase (1792–1794) led, in the face of internal and external counter-revolutionary threats, to the establishment of a republic with radical democratic features and to the formation of a revolutionary government that pursued all "enemies of the revolution" with the means of terror and the guillotine .

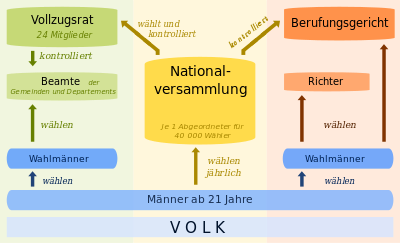

- In the third phase, the directorate from 1795 to 1799, a political leadership determined by bourgeois interests only with difficulty asserted power against popular initiatives for social equality on the one hand and monarchist restoration efforts on the other.

In this situation, the decisive factor of order and power increasingly became the civil army that emerged in the Revolutionary Wars , to which Napoleon Bonaparte owed his rise and support in the realization of his political ambitions that extended beyond France.

A main event in European history with an impact on history

The French Revolution is described in a more recent overview as a founding event that shaped the history of modernity more profoundly than almost any other. This revolution is of enormous importance not only in the minds of the French. With the declaration of human and civil rights of August 26, 1789, those principles were affirmed on the European continent and placed against absolutist monarchies that were laid out in the declaration of independence of the North American colonists and that are now being propagated and demanded worldwide by the United Nations .

For states with a written constitution and corresponding civil rights guarantees , the three-phase revolution has produced several models, each with different accents in terms of freedom, equality and differentiation of property (such as the right to vote ). Contemporaries of the revolutionary event said soon after July 14, 1789 ( storming of the Bastille ): "We have crossed the area of three centuries in three days." This was followed by a social and political-cultural upheaval in the one for political groups just as in some cases for disadvantaged sections of the population such as the sans-culottes publics were created through the printed media, which also had a say in political events in the subsequent 19th century.

In economic terms, the abolition of class privileges as well as the guilds and guilds promoted corporate freedom and the principle of performance. From a cultural point of view, the French Revolution largely dissolved the traditional alliance between church and state, with secularism showing the limits of religious teachings. Beyond France and the European continent, the revolutionary events stimulated new revolutionary movements , some of which saw themselves in agreement with the development in France, but some of which were also formed in contrast to it. There were also representatives of disadvantaged social classes who understood the slogans of freedom and democracy according to their own needs and tried to implement them: in the Atlantic area not least slaves , mulattos and indians .

As an object of experience and research for the interactions between domestic and foreign policy such as war and civil war, as an example of the dangers and instability of a democratic order and the dynamism of revolutionary processes, the French Revolution will remain a productive field of study in the future.

The pre-revolutionary crisis of French absolutism

Given the multitude of causes discussed in historical research in connection with the French Revolution, a distinction can be made between short-term, acutely effective and long-term, latent ones. The latter are z. This includes, for example, socio-economic structural changes such as the developing capitalism , which, together with the bourgeoisie who served itself, was restricted in its development by the feudal-absolutist ancien régime . The change in political consciousness, which found support with the Enlightenment, especially among the bourgeoisie, could be used by them as an instrument to assert their own economic interests. For the concrete emergence of the initial revolutionary situation of 1789, however, the factors that were currently exacerbated were decisive: the financial distress of the crown, the opposition of the official nobility (and, in connection with this, the country's inability to reform because the nobility blocked necessary reforms) and the inflation-related Brotnot especially in Paris .

Financial difficulties as a permanent problem

When the general controller of finances Jacques Necker published the figures of the French state budget ( French Compte rendu ) for the first time in 1781 , this was meant as a liberation to create a general readiness for reform in an otherwise hopeless financial crisis. His predecessors in office had already made unsuccessful attempts to stabilize public finances . Necker's figures were shocking: Income of 503 million livres (pounds) were offset by expenses of 620 million, half of which was accounted for by interest and repayments for the enormous national debt. Another 25% was devoured by the military, 19% by the civil administration and about 6% by the royal court. The fact that court parties and pension payments to courtiers totaled 36 million livres (5.81% of total government expenditure) was viewed as particularly scandalous.

The participation of the French crown in the war of independence of the American colonists against the British motherland also contributed significantly to the mountain of debt . The intended defeat and power-political weakening of the trade and colonial power rivals had occurred, but the price for the regime of Louis XVI. was twofold: Not only was the state finances additionally burdened, but the active participation of the French military in the liberation struggles of the American colonists and the consideration of their concerns in the opinion-forming French public weakened the position of absolutist rule on an ideological level.

Blockade of reform by the privileged

Like all his counterparts before and after him, Necker's plans to improve state revenues met with energetic resistance, which finally forced an already weakened monarchical absolutism to take action. The income and administrative system of the Ancien Régime was inconsistent and sometimes ineffective, despite centralistic tendencies, as embodied above all by the artistic directors as royal administrators in the provinces (see Historical Provinces of France ). In addition to provinces in which taxation could be regulated directly by royal officials ( pays d'Élection ), there were others where the approval of the provincial estates was required for tax laws ( pays d'État ). The first classes, nobility and clergy were exempt from direct taxes . The main tax burden was borne by the peasants , who also had to pay landlords and church taxes . Tax collectors were responsible for collecting taxes, who in return for a fixed amount to be paid to the crown could levy taxes from taxpayers and thereby keep surpluses for themselves - an institutionalized invitation to abuse. The main income was obtained from the salt tax ( Gabelle ), which was particularly hated by the people after numerous increases.

Ultimately, the supreme courts of law ( parlements ) were of decisive importance as a brake on reform, as they were able to validate the laws passed by the monarchical government, raise objections or withhold their consent. The parliaments were the domain of the nobility ( noblesse de robe ). Within their class, the official nobles were upstarts who had mostly acquired nobility status by purchasing offices . However , they were no less committed to safeguarding their privileges and interests than the long-established sword nobility (noblesse d'épée) . The increasing resistance to tax laws of the crown practiced in parliaments also found support among the people. After all attempts at intimidation by the court were unsuccessful and the initiative of Louis XVI. had failed to get the privileged to follow his course in a notable assembly specially convened in 1787 and 1788 , the government tried to curtail the privileges of parliaments. As a result, there was broad solidarity with the members of parliament. This culminated in unrest, which in Grenoble on " Day of the Bricks " anticipated the course and demands of the later revolution in many respects. Ultimately, the king could no longer avoid the reconstitution of the Estates General, which had been suspended since 1614 , if he did not want to let the crisis in the state finances escalate further.

Enlightenment thinking and politicization

The pre-revolutionary French absolutism showed weaknesses not only in a central field of practical politics and in the institutional area. Enlightenment political thinking also called its legitimacy basis into question and opened up new options for the organization of power. Two thinkers emerged from the French Enlightenment of the 18th century because of their special importance for different phases of the French Revolution: Montesquieu's model of a separation of powers between legislative , executive and judicial powers came into use during the first phase of the revolution, which resulted in the creation of a constitutional monarchy flowed.

Rousseau provided important impulses for the radical democratic second revolutionary phase, including by viewing property as the cause of inequality between people and by criticizing laws that protect unjust property relations. He propagated the subordination of the individual to the general will ( Volonté générale ) , refrained from a separation of powers and provided for the election of judges by the people. In the 18th century, enlightenment thinking found increasing dissemination in debating clubs and Masonic lodges as well as reading circles , salons and coffee houses, which encouraged reading and discussion of the fruits of reading in a sociable setting. The exchange of views on current political issues also had its place here, naturally and naturally. The main users were educated middle classes and professions, such as B. lawyers, doctors, teachers and professors.

The Encyclopédie published by Denis Diderot and Jean Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert , which appeared for the first time between 1751 and 1772, was a broadly effective product and compendium of Enlightenment thought . It became - translated into several languages - the enlightenment lexicon par excellence for the European educational world of the 18th century: “The humanities articles, which represented modern ideas and contained explosives, were packed between many picture panels and articles on technology, handicraft and trade as an ancien régime to undermine. "

Price increases as a social driving force

The majority of the population in the ancien régime was not very interested in enlightenment thinking and politicization, and even more so in the price of bread. The farmers, who made up four fifths of the population, had suffered a bad harvest failure as a result of the Little Ice Age in 1788 and then lived through a harsh winter. The climatic extremes of this decade could also have been intensified by the volcanic eruption of June 8, 1783 in Iceland . While the peasants lacked the bare essentials, they saw the storehouses of the secular and spiritual landlords to whom they had to pay taxes, still well filled. There were protests and calls to sell at a "fair price" when grain prices rose sharply. The little people in the cities were also hit hard by the rise in food prices. In the middle of 1789, bread was more expensive than at any other point in the 18th century in France, and cost three times the price of the better years. Craftsmen in cities had to spend around half of their income on bread alone. Every increase in price threatened the existence of the country and caused the demand for other everyday goods to fall. “Now dissatisfaction and excitement also reached those who had not yet been directly reached and mobilized by the public debate about the financial misery and the inability of the state to function. The economic hardship, which affected urban consumers and then also trade and commerce as a result of inflation and underproduction, brought the 'masses' onto the political stage. "

1789 - a complex year of revolution

In general consciousness, 1789 is the year most closely linked to the French Revolution, not only because it marked the beginning of a great political and social upheaval process, but also because it was the year that laid the foundations for an awareness of the national unity of all French people . This was also possible because of the multi-track nature of the revolutionary events, which gradually cast a spell over the entire population and in which three components worked together and interacted: the turn of the representatives against the absolutist monarchy, the uprising of the urban population against the traditional rule - and administrative organs and the peasant revolt against the rural feudal regime . Without the popular actions, each with its own special motive, the representatives of the educated and property-owned bourgeoisie, who were inspired by the Enlightenment and determined to reform, would hardly have gotten far with their political ideas in 1789.

From the General Estates to the National Assembly

The general estates were convened due to the blockade and pressure from the privileged in parliaments and provincial estates. Above all, however, the members of the Third Estate , who made up more than 95% of the population, had positive expectations . In the complaints booklet , which was traditionally drawn up on such an occasion and given to the members of the Assembly, the peasants demanded relief for the taxes and special rights that their landlords claimed, while the sections of the bourgeoisie, determined by enlightened ideas, already demanded the transformation of the monarchy according to the English Role model aimed. As a common concern, the demand was formulated that the Third Estate should be upgraded in the General Estates compared to the clergy and the nobility. At their last meeting in 1614, each of the three estates was represented by around 300 people, whereby the vote of each estate had to be given uniformly, which ultimately resulted in a 2: 1 decision for the privileged estates.

Louis XVI responded tactfully to the demands: the Third Estate was allowed to double the number of MPs, but the voting mode in the Estates-General remained open. The opening ceremony on May 5, 1789 in Versailles did not bode well: the first two stalls were seated in large cloakrooms in reserved seats; the third estate deputies, who were required to wear simple black suits, had to see for themselves how they placed themselves. The Court still made no reference to the Rules of Procedure in the speeches. More than a month then passed with unsuccessful debates, as the majority of the privileged stalls insisted on the old conference and voting mode: separate deliberations for the stalls, each with a uniform vote per stand.

But especially among the lower clergy, the village and parish priests, who were close to the people, the front began to crumble massively when some of them joined the Third Estate on June 12 and began to follow its deliberations. From then on, events precipitated. At the request of the Abbé Sieyès , who had previously effectively propagated the paramount role of the Third Estate, its representatives declared on June 17th to represent at least 96% of the French population, named themselves National Assembly and called on both other Estates to join to join them. The clergy followed this call on June 19 with a narrow majority, while the nobility, apart from 80 of their representatives, sought the support of the king to maintain the old order.

Louis XVI scheduled a royal session for June 23rd and closed the boardroom until then. The now determined deputies, however, organized a meeting in the Ballhaus on June 20 , at which they vowed not to part before a new constitution was created. At the meeting on June 23, they resisted, stirred up by Mirabeau , all threats from the king. Bailly, as elected president of the assembly, refused to obey the master of ceremonies, who had brought the dissolution order, with the striking remark that the assembled nation should not take orders from anyone. Some nobles also stood in the way of the use of armed force against the Third Estate. When the Duke of Orléans , the king's cousin, sided with the National Assembly with a number of other nobles , Louis XVI. on June 27th and now ordered both privileged estates to cooperate.

From storming the Bastille to fighting against feudal rule

The political successes of the Third Estate were for the time being provisional, because at the same time as he gave in, the King had ordered troops to Paris, which worried the public and made the people fear a further deterioration in the food supply - especially in view of the more expensive bread than ever before. When the finance minister Necker, who was relatively regarded by the Third Estate as his guardian of interests at court, was dismissed by the king on July 11, this was regarded as an ominous signal to the Parisian population. The lawyer Camille Desmoulins emerged as the spokesman for popular anger: “Necker's dismissal is the storm bell for a St. Bartholomew's night among the patriots! The battalions of Swiss and Germans will kill us today. There is only one way out: to take up arms! ”Numerous city customs houses were spontaneously destroyed and the royal toll collectors chased away.

In view of the heated atmosphere, the electoral officers of the Third Estate, who had meanwhile been integrated into the royal Paris city administration, formed a citizens' militia on July 13th as an organizing element, the later National Guard . The people, however, pressed for armament. After an arsenal was plundered, they moved to the Bastille on July 14th to procure additional weapons and powder. Here there were other people willing to rebel for joint action against this negative symbol of absolutist rule, a crowd of around 5,000 in total. At the time, however, the city prison only housed seven prisoners with no political background.

The Bastille commander, Launay , who only operated with a small crew, allowed the crowd to penetrate unhindered into the courtyards, but then set fire to them. The besiegers had to mourn 98 dead and 73 wounded at the end of the day. When the excited crowd put the city administration under pressure, four cannons were positioned in front of the Bastille with the help of the military; Launay capitulated. The masses pouring in over the lowered bridges, who regarded the previous bombardment as treason, killed three soldiers and three officers; Launay was first dragged away, then killed, his head as well as that of the head of the royal city council, Flesselle, speared on pikes and displayed.

The leaders of the Ancien Régime reacted in a shocked and defensive manner. The Paris troops were withdrawn and recognition and protection promised to the National Assembly. At the head of the Paris administration was now Bailly as mayor; The National Guard was commanded by the liberal Marquis de La Fayette , who was influenced by the American War of Independence . The city administrations in the provinces of France were subsequently restructured in a similar manner (municipal revolution). On the morning of July 17th, the Count of Artois , the king's brother, was the first to leave the country, while Louis XVI. went to Paris under pressure from the people and put the blue-white-red cockade on his hat as a sign of approval of what had happened .

“Up until July 14, there was hardly any talk of the peasants,” said the historian Lefèbvre ; but without their support, he says, the revolution would hardly have succeeded. Peasant ownership of land made up about 30 percent of that of the nobility, clergy and bourgeoisie. There were only serfs in certain regions. The proportion of landless peasants who had to pay taxes to the landlord fluctuated regionally between 30 and 75 percent. “In general, half of the cattle growth and the harvest was due to the owner, but more and more often he enforced all sorts of other taxes…” In the course of the 18th century, rights were often reasserted by the noble and bourgeois landlords and entered in the land registers some of which had already been forgotten. A more recent interpretation of this phenomenon, often referred to as "feudal reaction", reads: "Capitalism penetrated everywhere through the cracks of the old order and made use of its possibilities."

Bad harvests and high prices hit many smallholder livelihoods, whose production was insufficient for self-sufficiency with food, twice, as the inflation also reduced the farmers' opportunities to earn additional income in the city. “In the spring of 1789 organized gangs of beggars appeared everywhere, moving from court to court, day and night, and making violent threats.” In the tense climate of the elections for the Estates-General and in reaction to the events in Versailles and Paris developed the so-called “great fear” ( Grande Peur ) of the “aristocratic conspiracy”, which was held responsible for all disgruntled developments and activities and which also took shape in all kinds of mere rumors. The phenomenon of the Grande Peur prevailed between mid-July and the beginning of August 1789, covered almost all of France for three weeks and accompanied the massive peasant attacks on castles and monasteries that took place from 17th to 18th centuries. July were looted and set on fire with the aim of destroying the archives with the documents on the rights of men and forcing the landlords to renounce their feudal rights.

End of the estates, declaration of human rights and triumphal procession of the Parisian women

The violence and the spread of the revolution in the countryside also alarmed the court and national assembly in Versailles. As a result of the events of July 14, the latter had become the sole decisive political authority from which the reorganization of the situation was expected. Now she came under pressure to act: the question, which had already been controversially discussed up to then, whether a human rights declaration should be promulgated before the constitutional deliberations were concluded, suddenly became acute.

Around 100 members of the Third Estate, who had met for joint deliberations in the Breton Club , prepared a surprise coup in the assembly, with which the holding back resistance of the privileged estates, who were hoping for more favorable times to preserve their vested interests, should be levered out . The maneuver succeeded with the support of liberal nobles, who in the night session of 4/5. August 1789 acted with grand gesture as a pioneer of the renunciation. This affected all personal services, manual and clamping services , the landlord's jurisdiction , privileged access to offices, the abolition of the purchase of offices and the church tithe , as well as privileges such as hunting and keeping pigeons. Serfdom, the tax exemption of the privileged classes and all special rights of the provinces and cities were abolished: “In a few hours the assembly had established the unity of the nation before the law, had basically done away with the feudal system and the rule of the aristocracy in the country the element of their wealth that distinguished them from the bourgeoisie was eliminated and the financial, judicial and church reforms were initiated. ”It was the end of the ancien régime organized by the corporate state.

The opening sentence of the decree summarizing the resolutions of this night session, which spread at lightning speed and almost abruptly ended the revolution in the country, read: “The National Assembly is completely breaking up the feudal regime.” For the peasants, however, the happy core message did not contain the whole truth. Serfdom and compulsory labor were abolished without replacement, but the other man's rights were only redeemable or redeemable, at an annual interest rate of 3.3 percent: “The political calculation is to convert the old man's rights into good bourgeois money and the interest for so long lets pay as the capital has not been paid back. The nobles save what can be saved at all, and the landowners of the Third Estate have a great advantage through the equality of noble and civil goods. "

After the rural population had been pacified in this way, the National Assembly continued its work on a declaration of human and civil rights , which was passed on August 26, 1789 and which begins with the assurance: “From their birth they are and remain People free and equal in rights. ” a. also property, security and the right to resist oppression, the rule of law , freedom of religion , opinion and press as well as popular sovereignty and separation of powers . Furet / Richet judge: "These seventeen short articles of wonderful style and intellectual density are no longer an expression of the cautious tactics and fearfulness of the bourgeoisie: by freely defining its goals and its achievements, the revolution gives itself a flag in the most natural way, which must be respected by the whole world. ”With this, bourgeois individualism received its public law Magna Charta .

The fact that the declaration only refers to men is not expressly mentioned in the text, but in keeping with the spirit of the times, it was almost self-evident - but not for the French legal philosopher and writer Olympe de Gouges , who published the Declaration des droits de la femme et de la in 1791 citoyenne (" Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizens "), in which she called for full equality between women and men.

The Jews were also initially denied recognition as citizens with equal rights . Repeated attempts failed because of resistance from Jean-François Reubell and other MPs, most of whom came from Alsace or Lorraine . They cited traditional anti-Jewish stereotypes such as the alleged usury and the exploitation of the rural population by the Jews, their cosmopolitanism and the alleged danger of foreign Jewish rule. Only the acculturated Sephardic Jews of southern France were granted civil rights in January 1790.

Louis XVI, whose signature was needed so that the decrees of the National Assembly could come into force, made all sorts of legal reservations and tried to get as strong a veto position as possible in the future constitution in return for his approval. In addition, he again ordered a foreign Flandre regiment ( Régiment de Flandre ) to Versailles, whose officers crushed the blue-white-red cockade under their boots at a royal banquet on October 1st. The process became known in Paris and heated up a mood that was already charged with the persistently high bread price and lack of supplies. Jean-Paul Marat , who had founded his newspaper “Der Volksfreund” in September 1789 , together with others kept the Parisians up to date and with warnings about the “conspiracy of the aristocrats” against the people in revolutionary tension.

On October 5th, a crowd of several thousand, consisting mainly of women ( Poissards ) , gathered in front of the town hall with the intention of moving to Versailles to assert their demands on the spot. They left Paris to the ringing of the storm bells; they were later followed by 15,000 national guardsmen and two representatives of the city administration with the task of bringing the king to Paris. Louis XVI received the women, promised food deliveries and, under the impression of distress, signed the decrees of the National Assembly. The situation seemed relaxed; but the women stayed overnight, guarded the castle and also attacked the National Assembly with their demands for bread and heckling.

The following morning they pushed into the castle and, together with city officials and national guardsmen, forced the king's concession to move to Paris. The National Assembly followed suit. “In the early afternoon, the endless train made its noisy way to Paris. National Guard units marched at the head; there was a loaf of bread on each bayonet. Then the women follow, armed with pikes and rifles or swinging poplar branches; they accompany the grain wagons and the cannons. Behind the disarmed royal soldiers with the tricolor cockades of the life guards, the (Régiment de Flandre) and the Swiss Guard, the body with the royal family rolls slowly like a hearse [...] The carriages of the deputies follow, and the huge one forms the end Crowd with the main body of the National Guard. As if the symbolic power of this procession was not yet clear enough, the people shout: 'We are bringing the baker, the baker's wife and the baker's boy!' ”From then on, the monarch and the national assembly would be exposed to the pressure of the people in the capital Paris.

The constitutional monarchy

The move of the king and court to Paris, followed by a limitation of the financial resources that the crown subsequently had at its disposal under a so-called civil list approved by the National Assembly, weakened the position of Louis XVI. in addition, he remained a central figure in the political game of forces. Apart from a small minority, no one in the National Assembly intended to abolish kingship. However, there were differing positions on how much political influence the monarch should have under the future constitution. However, whether the new constitution could work at all depended on his approval. Any concrete version of the constitutional monarchy was bound to fail because of a principled refusal of the king.

The National Assembly on the way to a constitution

The stormy riots and upheavals of 1789 followed, favored by a good harvest and the improved supply situation, the “happy year” 1790, which culminated in the federation festival on the Champ de Mars on the anniversary of the Bastille conquest: “In front of hundreds of thousands of cheering spectators Here 60,000 national guards from all parts of the country with the National Assembly took the oath of allegiance to nation, law and king at the 'Altar of the Fatherland' and solemnly celebrated the fraternization of the French nation. "

The constitutional deliberations of the National Assembly, which was divided into a large number of thematic committees, made considerable progress. Before the end of 1789, the urgent problem of restructuring state finances was tackled with revolutionary vigor: All church property was nationalized and converted into national property. The entirety of these national goods served as cover for a new paper money currency, the assignats . Since the clergy from church property no longer had any income at their disposal, they were dependent on state salaries. The civil constitution of the clergy eventually stipulated that pastors were to be elected like other civil servants, and a decree required them to read and comment on the ordinances of the National Assembly from the pulpit. At the beginning of 1790, the previously unequal provinces were replaced by a new division into 83 departments with a uniform subdivision and administrative structure. The city and internal tariffs within France have been lifted. In the judiciary, the election of judges - among those with legal training - was introduced instead of the ability to buy office, a judicial hearing within 24 hours and compulsory defense by a lawyer prescribed for arrested persons.

In terms of the right to vote, the bourgeois reservations in the assembly were decisive; One went behind the general (male) suffrage practiced for the elections to the Estates General: Only so-called active citizens with a certain minimum tax revenue were allowed to vote. The main reason for this restriction was the consideration that only a citizen who could not be bought and who was thus independent should exercise the right to vote. Only the lawyer Robespierre castigated this as a violation of the legal equality guaranteed in the human rights declaration. The most delicate problem of the Constituent Assembly, however, remained the question of whether and how it could succeed, Louis XVI. to be built into the new political system. Above all in this question there were very different ideas and the tendency to form political camps, which justified the right-left scheme, as it later became common. The "aristocrats", members of the first two estates and supporters of the Ancien Régime, the Louis XVI. not only left the executive power, but also wanted to give him an absolute veto in the legislation. In the direction of the middle of the hall and across to the left, those MPs followed in gradations who supported the king's participation in the legislative process only to a small extent or who rejected it entirely.

In the exploration and mediation process between the assembly and the king, a number of outstanding figures from this first phase of the revolution - ultimately in vain - got involved. Sometimes compromised by supposed or actual proximity to the court's interests, such as B. the temporary presidents of the National Assembly Bailly, Mounier and Mirabeau , the commander of the National Guard La Fayette and the "triumvirate" Barnave , Duport and Lameth . According to the constitutional text, the king was finally granted a suspensive veto right, which could block a legislative project for two legislative periods. On the other hand, as the head of the executive , he was limited in his ability to act. Because as a result of the electoral principle, the judiciary and administration were not dependent on the king and his ministers, especially since the administrative regulations were not issued by the ministries but by the National Assembly. Although he remained chief of the armed forces, he only had the right to appoint officers for the highest ranks, while the crews often sympathized with the revolution and fraternized with insurgents .

The forces of the counter-revolution

The revolutionary events between July and October 1789 had triggered waves of emigration within the two formerly privileged estates and led to assembly points at small royal courts, for example in Turin, Mainz and Trier, from which counter-revolutionary activities emanated, which both destabilized the new order in France and brought it about aimed at foreign intervention. Moderate support for this came from the Russian, Spanish and Swedish sides, where they spoke out in monarchical solidarity for the restoration of the Ancien Régime - but were not ready for more for the time being.

The abolition of feudalism in France also affected the claims of foreign princes in some cases. B. with papal possessions in southern France and with those of German imperial princes in Alsace . Neither their request to intervene, addressed to Emperor Leopold II , the brother of the French Queen Marie Antoinette , nor a personal encounter with the emigrated Count von Artois, the brother of Louis XVI, were initially able to induce the Habsburg to take military action. Not only he had no interest in a war against France due to other warlike entanglements, such as the war of Russia and Austria against the Ottoman Empire in 1790 and the national uprising of Poland the following year and did not allow himself to be harnessed for the purposes of the emigrants. Their military activities close to the border, carried out by bases such as B. Koblenz and Worms were started from, for the time being did not have the desired effect, even if they fueled panic fears of the conspiracy of the aristocrats in the East.

Energetic and sustained resistance, which in some cases soon took the form of open rebellion and a religious war, sparked a decree of the National Assembly in connection with the civil constitution of the clergy, which on November 27, 1790 required all priests to take an oath on the new constitution. Pope Pius VI , who had already described the declaration of human rights as "godless", forbade the oath on punishment of excommunication . Only just under half of the clergy, mainly from the lower clergy, then took the oath. From then on, France was religiously divided, because the rural population in particular sought out priests who refused to take oaths for baptism and other core religious ceremonies. "The revolution provided the general staff of the counter-revolution, which was without troops, the necessary foot soldiers: the oath-refusing priests and their sheep."

The King's Flight

The church policy of the Constituent Assembly represented an additional challenge for Louis XVI, who practiced worship in the Tuileries Castle in the traditional way, as he was forced to receive communion from priests who refused to oath in public . In February 1791, Marie-Antoinette wrote to Leopold II to appeal not to delay any longer and to use military means to counter the rapidly advancing revolution, which threatened to spread to the Austrian Netherlands . When Louis XVI. was then prevented by the crowd in April from leaving Paris for one of his usual spa stays in Saint-Cloud , the royal family's secret escape plans must have become a priority. On the night of 20./21. On June 6th, 1791 she managed to escape undetected from the castle guarded by national guards in disguise, in order to get out of the country in carriages. The goal was the Austrian Netherlands, with whose military support Louis XVI. hoped to return to France and restore his absolutist rule.

The king did not exercise particular caution during the escape , so that he was recognized several times during his stay. The tour company, which was already lagging behind in the schedule, was overtaken by reports of their being on the road and finally stopped not very far from the Belgian border near Varennes . The repatriation of the royal family triggered a mass riot in Paris that also included the roofs of houses. However, nothing remained of the noisy enthusiasm that the forced arrival of the king in October 1789 had triggered among the Parisians. A heavy silence lay over the scene. In the National Assembly, which saw its constitution endangered, Louis XVI. held in contradicting ways. On the one hand, against better judgment, the reading was spread that the king had been kidnapped; on the other hand, he was released from his monarchical functions until the still-to-be-completed constitution could be presented to him for signature. Barnave warned in the July 15, 1791 debate: “Do we want to end the revolution or do we want to start over with it? [...] With one more step forward we would be burdening us with disaster and guilt, one step further on the path of freedom would be the destruction of royalty, one step further on the path of equality would be the destruction of property. "

During his escape, Louis XVI. left behind a counter-revolutionary proclamation that was initially unknown to the public. In it he had emphasized u. a. the in his view ominous role of the political clubs and their significant influence on the decisions of the Constituent Assembly. As it now turned out, it was precisely his flight that led to a new formation and radicalization of these extra-parliamentary political organizations. The Breton Club, which was decisive in Versailles until October 1789, had found its meeting place in Paris as the “Society of Friends of the Constitution” in the Jacobin monastery and was therefore called the Jacobin Club . As early as the end of 1790, it spread to 150 branches across the country and actually had a great impact as a place for political opinion-forming, with the Parisian original also exerting a preliminary advisory influence on the decision-making process in the National Assembly. The escape of the royal family resulted in the question of the deposition of Louis XVI. to split the Jacobin Club: As the Left came to Robespierre for the removal of the king, the majority of the line of La Fayette and Barnave dividing members of the club went out and founded in the former Feuillants Monastery the club of the Feuillants . There were also spin-offs at the subsidiaries; however, the Paris Jacobins also succeeded in maintaining a clear predominance in the branches of the same name by means of a campaign for universal suffrage, which was only just beginning.

Since the membership fees in the Jacobin Club were relatively high, there were soon numerous other clubs and popular societies with easier access. The most influential among them was the Cordeliers Club , which met in the Franciscan monastery , was a discussion and struggle club for the enforcement of human rights and for the detection of abuses of public power. Marat, Desmoulins and Danton had a significant say in it and gained political influence through him. After the king's flight, it was from here that the first call for the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic came from. On July 14, 1791 and again three days later, large-scale demonstrations took place on the Champ de Mars , where signatures for the deposition of the king were now collected at the altar of the fatherland. La Fayette had the second meeting dispersed by the National Guard with volleys of rifles, with numerous deaths. An unmistakable rift now separated the National Assembly and the Parisian People's Societies.

A multi-motivated war

The courtyards with whose support Louis XVI. had expected on his escape, it took a good month for a reaction. Then Emperor Leopold II and the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm II declared in the Declaration of Pillnitz the situation of Louis XVI after his escape. to the common interest for all kings of Europe. Both monarchs put military intervention in favor of Louis XVI. in prospect if a grand coalition of the European powers were to come to this end. But then no serious efforts were made to implement this plan. The threat only resulted in the French revolutionary supporters harboring even greater bitterness against the "aristocratic plot".

In September 1791, the constitution of the Constituent Assembly came into force with the participation of Louis XVI, who swore the oath on the constitution. On September 27th, the National Assembly passed the full civil equality of all Jews in France.

On October 1, the newly elected legislature was constituted, to which no member of the constituent could belong. The Feuillants made up a clear majority over the Jacobins; the largest group of representatives did not belong to either of the two camps.

The big issue and the reason why the legislature did not even last a year became the Revolutionary War. However, this did not come from the European powers, but from France itself. According to the new constitution, cooperation between the king and the legislature was necessary for this. For Louis XVI. and Marie-Antoinette, after the failed attempt to escape, war was the only way to restore conditions that were acceptable to her. They reckoned with a quick defeat of the French army and with the help of the victors in reversing the changes caused by the revolution.

In the legislature, of course, the motives and arguments were of a different kind, but led to the same result of the advocacy of war. It was believed among feuillants like La Fayette that a short, limited war would strengthen the generals and enable them to stabilize the revolution. A veritable revolutionary enthusiasm for war was fueled by the MP Brissot from the Left: “The power of reasoning and the facts convinced me that a people who have achieved freedom after 10 centuries of slavery must wage war. War must be waged to put freedom on an unshakable foundation; it must wage war to wash freedom from the vices of despotism, and finally it must wage war to remove from its bosom those men who might spoil freedom. "The MP Isnard seconded:" Do not believe ours present situation prevent us from delivering those decisive blows! A people in a state of revolution is invincible. The flag of freedom is the flag of victory. ”Only Robespierre in the Jacobin Club strongly opposed this:“ The most eccentric idea that can arise in the mind of a politician is the idea that it would be enough for one people to penetrate another people by force of arms to get it to adopt its laws and constitution. Nobody likes the armed missionaries; and the first advice given by nature and caution is to repel the invaders like enemies. "

On April 20, 1792, only seven members of the legislature voted against the declaration of war on the King of Bohemia and Hungary. In the euphoria of the first days after this decision, the Marseillaise was created for the Rhine Army in Strasbourg , which is still the national anthem of France today ("Allons enfants de la patrie ...").

The reality of the war, on the other hand, quickly became sobering and embittering. Officers and men put up so little resistance to the allied Austrians and Prussians that betrayal was soon suspected and a mobilization began in the Parisian sections, through which sans-culottes armed with pikes became a permanent feature in the streets and on the grandstands of the city. A concentrated advance into the Tuileries on June 20, 1792 ended peacefully with the beleaguered king, who had just appointed an unwelcome new ministerial team from Feuillants, put on the red Jacobin cap.

On July 11th, however, the legislature issued a proclamation declaring the “fatherland in danger”. All citizens who were capable of weapons were asked to register as volunteers, should wear the national cockade and were sent to the armies. In the provinces, the hostile mood intensified. One spoke because of the uncooperative attitude of Louis XVI in important fields. and Marie-Antoinettes, meanwhile, often only disparages the legislature of "Monsieur et Madame Veto" and of the "Austrian Committee", which rules at court and sabotage patriotic efforts. From Marseille a battalion of volunteers set out for Paris for the Federation Festival. Because of their chants, the song from the first days of the war became known and popularized as the Marseillaise (hymn of the Marseilles).

The first French republic

In the events that brought about the overthrow of the monarchy, the establishment of the republic and the formation of a revolutionary government and terror in the radical democratic phase up to July 1794, the revolutionary historian Lefèbvre interpreted a specific revolutionary mentality as the cause, which was already the storm on the Bastille and the other popular actions of 1789 and which only gradually receded after the revolutionary achievements had been consolidated. According to Lefèbvre, it consisted of three components: the fear (peur) of the “aristocratic plot”, the defensive reaction (réaction défensive) , which included the self-organization of ethnic groups and the implementation of resistance measures , and the will to punish the anti-revolutionary opponents (volonté punitive ). The war summer of 1792, which was marked by bad news for revolutionary supporters, set lasting accents in this regard. After 1789 it led to a "second revolution".

By popular elevation to the national convention

At the beginning of August 1792 the Manifesto of the Duke of Brunswick , the commander in chief of the Prussian and Austrian troops ready to invade France, became known in Paris . With a view to the goal of freeing the royal family from captivity and Louis XVI. to restore his traditional rights, called for the unresisted submission of the French troops, national guards and the population. Wherever there was a defense against it, the manifesto threatened to destroy the apartment and burn it down. Paris was specially highlighted and anyone with any political responsibility in the city was offered the prospect of court martial and the death penalty if they were insubordinate .

The intended effect of this proclamation was reversed. In the Paris sections which, with the exception of one, had already spoken out in favor of the removal of the king - albeit unsuccessfully in relation to the National Assembly - preparations were now being made for the uprising. On the morning of August 10, 1792, the sections formed an insurgent commune (commune insurrectionelle), which drove out the previous city administration and took its place. The acting commander of the National Guard was killed and replaced by the beer brewer Santerre . Masses of artisans, small traders and workers moved together with those in Paris for weeks to remove Louis XVI. urging foreign federations before the Tuileries and stormed them against the resistance of the Swiss Guard . Hundreds of deaths on either side were the price of the Tuileries Tower . The royal family had already fled to the National Assembly before the attack, which, however, under pressure from the angry masses, decided to temporarily remove the king and keep him in prison.

With the revolutionary Commune of Paris, a rival political body had appeared alongside the National Assembly, which subsequently claimed significant influence of its own. Since so-called passive citizens who were not entitled to vote were increasingly able to assert their interests first in the Paris section assemblies and then with the commune, the legislature formed according to the census suffrage suddenly lost its authority due to the popular action of August 10th. Therefore she was forced to dissolve herself in the course of new elections according to general (male) suffrage for a national convention. For the transitional period, a provisional executive council was entrusted with the previous government functions of the king. The constitution of 1791 was thus obsolete.

By the end of August, the advance of the Prussian-Austrian troops with the capture of Longwy and Verdun became increasingly threatening for Paris. A special draft of 30,000 men to defend the capital was then decided by the legislature, and the municipality even doubled the number. Meanwhile, following the August 10 overthrow, the sections had set up monitoring committees for anyone suspected of being anti-revolutionary. Through house searches and arrests, to which court servants, feuillants, journalists and oath-refusing priests were exposed, the prisons were completely overcrowded. In this situation, as the volunteer troops were now preparing to move against the Prussian-Austrian associations under the Duke of Braunschweig, the prison inmates appeared to be a threat to the revolutionary metropolis from within. In a spontaneous action by federates, national guards and sans-culottes, who implemented the resolutions of individual section assemblies , between 1,100 and 1,400 prison inmates were slaughtered from September 2nd to 6th .

In this tense situation, the elections to the National Convention took place with only around 10% participation. In Paris, this was done with open voting to the exclusion of supporters of royalty. When the National Convention met for its opening session on September 21, 1792, the omens seemed more favorable than shortly before: It was the day after the Valmy cannonade , in which the French revolutionary army was victorious and the external threat averted for the time being.

Girondins, Montagnards and the judgment against Louis XVI.

The term National Convention ( convention nationale ) for the now third French National Assembly signaled two core competencies: the drafting of a new constitution and the preliminary undivided exercise of all competences of national sovereignty (or state authority). With its first resolutions, the Convention made the situation clear in this regard. The monarchy was abolished, the republic was founded and a new era was introduced: September 22, 1792 was the first day of year I of the republic.

This relatively unanimous commitment to the second revolution of August 10th initially concealed the division into different political camps that was soon expressed in the seating arrangements of the members of the convention. On the right side of the house, the supporters of Brissot, then called Brissotins, later Girondins (after the Gironde department , from which some prominent members came) gathered . With their advocacy of property protection, free trade and market pricing, they were on the side of the economic bourgeoisie. They opposed the demands of the Paris section assemblies and the insurgent commune and tried to use the influence of the federated in the departments.

Their opponents in the convent sat in the higher rows of seats, as it were on the mountain, and were therefore called Montagnards . Like the vast majority of the members of the Convention, they too belonged to the middle and upper middle class, including above all civil servants and members of the liberal professions, especially lawyers. They held over their leading heads - u. a. Danton, Robespierre, Marat - unlike the Girondins, close contact with the sections and popular societies, their interests opened up and made themselves their spokesmen in the Convention.

In the "plain" (plaine) or in the "swamp" ( marais ) between Girondins and Montagnards sat the majority of MPs who did not join either of the two camps, but depending on the subject matter and the general political climate, sometimes with one, sometimes with the other Side agreed. The fact that 200 Girondins outnumbered the approx. 120 Montagnards clearly outnumbered the approx. 120 Montagnards, out of a total of 749 convent members, did not have to be the decisive factor, even if the Girondins found majority support for their liberal course in the relaxation phase after Valmy and were even courted by Justice Minister Danton.

The simmering question of how to proceed with the deposed and imprisoned king came urgently on the agenda of the convention at the end of November when Louis XVI's correspondence was burdensome in a secret cabinet in the Tuileries. was discovered with emigrants and anti-revolutionary princes. After this, a high treason trial turned out to be inevitable. The Convention itself formed the court. In its deliberations from January 16 to 18, 1793, the convention decided against the reluctant Girondins, who wanted to spare the king and left the Jacobin Club when they could not prevail there, after two hearings of the accused on December 11 and 26, 1792 majority that Louis XVI. had been guilty of the conspiracy against freedom that the people - unlike the Girondins wanted it - did not have to decide by plebiscite that they should suffer the death penalty, without delay.

On January 21, the only person addressed in the trial as Louis Capet was guillotined on the “Place de la Révolution” (today Place de la Concorde ). Apart from a few royalist protests, the country remained largely calm: “Except in Paris and in the meetings, the trial of Louis XVI is calling. no enthusiasm. This silence of an entire people at the death of their king shows how deep the break with the centuries-old feelings of the people already is. The anointed of God, the one endowed with all healing powers, becomes once and for all with Louis XVI. to dust. Twenty years later you can reestablish the monarchy, but not the mysticism of the consecrated king. "

Jacobins and sans-culottes in the radicalization process

The guillotination of Louis XVI triggered violent reactions. abroad. Great Britain became the driving force, where the court put on mourning clothes and the French envoy was expelled. The offensive warfare and annexation policy of the Convention since the victories of Valmy and Jemappes as well as the damage to British economic interests in Holland made British Prime Minister Pitt head of a coalition of European powers against republican France after the French declaration of war on February 1, 1793 . Just two months later, the revolutionary armies that had been pushed back were fighting again to defend their own national borders - and within France for the continuation of the revolutionary results.

In view of the superiority of the opposing forces, the Convention decided on February 23 to raise another 300,000 men and left it to the departments to decide which procedure to use to collect the contingent allocated to them. This requirement triggered counterrevolutionary displeasure above all in the rural-conservative Vendée in western France , where armed uprisings had spread like wildfire since the beginning of March and soon escalated into a civil war that also found nourishment in other parts of the country. The decree of the convention, which threatened all armed rebels with the death penalty and the confiscation of property, had no effect for the time being, as did the deployment of revolutionary troops.

The convent was also under pressure in the spring of 1793 from the Parisian sans-culottes, whose unrest was also fueled by price inflation. From the end of January to the beginning of April alone, the actual value of the assignats had dropped from 55% to 43% of their face value. Despite the satisfactory harvest in 1792, the farmers kept the market supply low in anticipation of further price increases. The economic-political demands of the sans-culottes, which were regularly raised in such a situation, aimed at determining the existing stocks of food supplies, confiscating parts of the production from farmers and traders, setting maximum prices (or a price maximum) and the exchange rate of the assignats as well as the Punishment of usurers.

While the Girondins categorically refused to accept such demands, the Montagnards were more willing and, under the pressure of the circumstances, dragged along with them the majority of the Plaine MPs who wanted the Convention to keep the political initiative and not from the Parisians Sections and the commune was overrun. Marat countered Girondist warnings about the dictatorship: "Freedom must be created by force, and now the moment has come to organize the despotism of freedom for a certain period of time in order to crush the despotism of kings!"

In March 1793 a revolutionary tribunal was created to judge opponents of the revolution and suspects; The monitoring committees subsequently set up in the communities served as suppliers. The compulsory rate for assignats, a maximum price for grain and flour and a compulsory loan to be raised from the rich followed in April and May. A welfare committee was created for the government functions , to which a majority of Plaine members was initially elected on April 11, but in which Danton exercised the decisive political influence. His guideline for the establishment of the Revolutionary Tribunal was, in memory of the September murders of the previous year: "Let's be terrible, so that the people don't have to be!"

The Girondins, on the other hand, sought a dispute with the Parisian sans-culottes, emphasized that Paris was only one department alongside 82 others, and set up a purely Girondist commission to control the activities in the Parisian sections. The MP Isnard escalated the conflict with a threat reminiscent of the Duke of Brunswick's manifesto: “[...] should the representation of the nation be affected by an uproar such as has been incessantly re-instigated since August 10th I hereby declare on behalf of the whole of France that Paris would be wiped out of the earth; soon, looking at the banks of the Seine, one would wonder whether this Paris really existed. "

The decision was prepared by an insurgent committee apart from the sections that normally lead the popular movement and the commune, which in several attempts from May 31 to June 2, 1793 finally managed to surround the convent with 80,000 men and threaten it with over 150 cannons . Against the resistance of the Montagnards, the extradition of the leading Girondins was ultimately demanded, so that the convention finally took the decision to place them under house arrest. With the retirement of the Girondins from the convent began that phase of the French Revolution, which is often referred to as the "Jacobin rule".

A revolutionary dictatorship to save the republic

The expulsion of the Girondins from the convention also made the draft constitution, which was largely shaped by the Enlightenment philosopher Condorcet , obsolete, which provided for a strict separation of powers, a consistent system of representation and greater political independence and co-creation competence for the departments. Until the new constitution was passed on June 24, 1793 - mainly by Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles , Georges Couthon and Louis Antoine de Saint-Just - accents were hastily shifted in favor of social equality, a right to work and duty highlighted to oppose a government hostile to the people and, in addition to the individual's right to property and free disposal, also emphasized the obligation to subordinate to the general will. This republican constitution, confirmed by referendum, was postponed to peacetime by the convention because of the threatening war situation and actually never came about. The conflict was exacerbated by the civil war fomented by supporters of the Girondins in the departments.

The murder of the radical revolutionary Marat by the Girondin Charlotte Corday on July 13, 1793 as well as uprisings against the rule of the Paris Rump Convention, which u. a. broke out in Lyons, Marseilles, Toulon , Bordeaux, and Caen, the sans-culottes kept in tense excitement and the convent under pressure. Only now was the final liberation of the peasants from all remaining documentary feudal charges that had to be redeemed, and the expectations aroused in the countryside in 1789 met. At the same time, the sale of expropriated emigrant property and dismantled into small plots began. With this, the increasing number of small farmers was tied to the revolution. The Parisian sans-culottes could not be satisfied in this way.

Jacques Roux , the spokesman for a particularly radical sans-culottes group, had already presented the “Manifesto of the Enragés” (the angry ones) in the convent on June 25, 1793, the day after the constitution was passed. a. read: “Now the constitution will be handed over to the sovereign. Did you outlaw speculation in it? No. Have you pronounced the death penalty for smugglers? No. […] Now we explain to you that you have not done enough for the happiness of the people. ”On July 26th, the convent then decided on the death penalty for grain buyers. Even with the measures for the military defense of the republic against the external and internal enemies, the Convention was pushed to extremes in August 1793 - contrary to its concerns about the consequential organizational problems: “From that moment on until the point in time when all enemies left the territory of the Republic will be chased out, all French are in constant deployment for army service. The young men go into battle; the married will forge arms and move supplies; the women will make tents and clothing and work in the hospitals; the children will make bandages out of old laundry, and the old people will go to public places to strengthen the fighting morale of the warriors and to proclaim their hatred of the kings and the unity of the republic. "

At the beginning of September, when the supply situation deteriorated again, economic policy demands, for example from the Sans-Culottes section, were loud: “Each department is granted a sufficient sum so that the price of basic food can be kept at the same level for all residents of the republic. […] A maximum should be set for assets. [...] Nobody should be allowed to lease more land than is needed for a fixed number of plows. A citizen should not be allowed to own more than a workshop or a shop. ”Another spokesman for the radical wing of the sans-culottes, Jacques-René Hébert , editor of the people's newspaper“ Le père Duchesne ”, brought charges against the“ sleepers ”in the convention and contributed significantly contributed to the fact that there was another action by the Parisian common people on September 5, 1793, who surrounded the convention en masse and then peacefully occupied it in order to aid the deliberations of the representatives. They achieved immediately that a revolutionary army was formed from sans-culottes, which should ensure the capital supply with grain and flour and persecute usurers and smugglers. At Danton's suggestion, daily allowances of 40 Sous were to be paid out to all needy people at state expense for attending two Section meetings a week. In addition, it was decided to arrest the suspects, thus opening the way to the reign of terror. With the introduction of the general maximum for prices - as well as for wages - at the end of September another key economic policy demand of the sans-culottes was taken into account.

In this phase of the revolution, the claim to leadership and determination emanated mainly from the reformed welfare committee in which Robespierre pulled the strings after Danton's departure. On October 10, 1793, Saint-Just, Robespierre's close companion in the Convention , urged a clear mandate for the revolutionary government of the welfare committee: “In view of the circumstances to which the republic is currently exposed, the constitution cannot be enacted; the republic would be ruined by the constitution itself. [...] You yourself are too far from all crimes. The sword of the law must intervene at breakneck speed everywhere, and your power must be omnipresent to stop the crime. [...] You can only hope for good prosperity if you form a government that will be mild and indulgent towards the people, but terrible towards itself because of the energy of its decisions. […] It is also useful to remind the representatives of the people in the armies emphatically what their duties are. They should be fathers and friends of soldiers in the armies. They should sleep in the tent, be present during military exercises, not enter into confidentiality with the generals, so that the soldier has more confidence in their justice and impartiality when he brings a matter to them. Day and night the soldier should find the representatives of the people ready to listen to him. "

Indeed, during this period the republic had to fight primarily a military struggle for survival. The convention sent commissioners (the representatives of the people addressed by Saint-Just) to the various war and civil war fronts, who were supposed to ruthlessly clean up unreliable army commandments. Generals suspected of negligence were to be judged by a military court and replaced by tried and active younger officers, partly at the suggestion of the men. The reorganization of the revolutionary armies was mainly led by the military engineer Lazare Carnot , also a member of the welfare committee. The remnants of the old line troops were combined with the recently dug up to form new troops loyal to the revolutionary government. At the turn of the year 1793/1794, the first successes of these measures became apparent, also because as a result of the mass mobilization the numerical preponderance of the revolutionary armies began to outweigh the pressure of the multi-front war. An end to the threat to the republic still seemed a long way off, both in the Vendée and on the north-eastern borders of France.

Legalized terror and de-Christianization

The Revolutionary Tribunal created in March 1793 had sentenced "only" about a quarter (66 people) to death of 260 defendants by the September action by the Parisian sans-culottes. To the insurgents this seemed completely inadequate, as their petition dated September 5, 1793, submitted to the Convention: “Legislators, the time has come for the unholy struggle since 1789 between the children of the nation and those who have failed them to put an end to it. Your and our destinies are bound up with the unchanging institution of the republic. Either we have to destroy their enemies or they have to destroy us. […] Hallowed Montagne, become a volcano whose hot lava destroys the hopes of the villains forever and burns those hearts that still have a thought of royalty! Neither mercy nor mercy for the traitors! Because if we don't beat them, they will beat us. Let us set up the barrier of eternity between them and us! "

In this respect, too, the mass appearance of the sans-culottes in the convent did not fail to have the intended effect. On September 17, the Montagnards and Plaine MPs passed the law on suspects, which included anyone “who, through their conduct or relationships, or through oral or written views, was supporters of tyrants, federalism and enemies of freedom have given to know "; in addition all former nobles and their relatives "who have not permanently demonstrated their ties to the revolution", as well as all emigrants who have returned to France. The locally responsible monitoring committees had to draw up a list of the suspects, draw up the arrest warrants and arrange for them to be transferred to prison, where the detainees were to be kept at their own expense until peace was concluded. A list of internees was to be sent to the General Security Committee of the Convention.

Also on the line demanded by the sans-culottes was an acceleration of the proceedings in the Revolutionary Tribunal, which increasingly made short work of the defendants: the convicts of this period already reflected the drama of the history of the revolution up to that point. In addition to Marie-Antoinette, Charlotte Corday and Olympe de Gouges, Feuillants and Girondins also had to climb the scaffold , including leading figures in the three successive national assemblies such as Bailly, Barnave and Brissot. Vergniaud , one of the most prominent speakers in the Gironde and who was also affected, put the events into the formula: "The revolution, like Saturn, eats its own children."

While the condemned Girondins were being carted to the place of execution on the morning of October 31, 1793 , they began singing the Marseillaise loudly and were only silenced by the guillotine: "The chorus grew weaker the more often the sickle fell. Nothing could stop the survivors from singing on. One heard them less and less in the huge square. When the serious and holy voice Vergniauds recently sang alone, one would have thought to hear the dying voice of the Republic and the law ... "as Madame Roland , the once influential wife of former Girondist Interior Minister Roland on November 8, the scaffold in the Place de la Révolution, she greeted the monumental Statue of Liberty erected nearby: "O freedom, what crimes are being committed in your name!"

Among the early adversaries of the revolution were the oath-refusing priests; After the Girondins had been eliminated from the convent in the summer of 1793, most of the constitutional clergy had also gone over to the counter-revolutionary camp. This z. Some of the anti-church tendencies that already existed strengthened and broke new ground in some places. In the context of a convention mission against federalist insurgency areas, the deputy Fouché , who was in Nevers u. a. ensured that the church bells were melted down, had a bust of Brutus consecrated in the cathedral and organized a civic festival. Something similar happened in Paris on November 7th, where Bishop Jean Baptiste Joseph Gobel was forced to abdicate before the convent and Notre Dame Cathedral was rededicated into a temple of reason. A convent decree made it free for every congregation to renounce religion. In Paris, revolutionary committees and popular societies ensured that at the end of November all the churches of the capital city were consecrated and that a cult for the martyrs of freedom (Marat, Lepeletier , Chalier) was introduced in all Parisian sections . Although the convention issued a decree on December 6, 1793 on Robespierre's initiative, which affirmed the right to freedom of religion, de-Christianization and the temporary closure of the church have left lasting traces.

Robespierrists, Hébertists and Dantonists in the decisive battle

In his turn against the excesses of the de-Christianization campaign, in which he was in agreement with Danton, Robespierre sought to put radical groups under the sans-culottes. As a constant guardian of popular interests and the general will, based on Rousseau, he had already distinguished himself in the Constituent Assembly and acquired the reputation of the "incorruptible" (L'Incorruptible) . “He will go far,” Mirabeau had prophesied, “he believes everything he says.” Robespierre had been chairman of the Jacobin Club since March 1790, where he had survived the splitting off of the Feuillants and the Girondins with his own authority. When he came to the Convention on December 25, 1793 to speak on the principles of the revolutionary government, he was at the zenith of his power as the strategic head of the Welfare Committee. Parts of his speech at the time shed illuminating light on the subsequent development up to his fall.

He urged the revolutionary government to be vigilant against two opposing poles that were equally destructive: “It must steer between two cliffs, weakness and audacity, moderantism and excess: moderantism, which is for moderation, what impotence is for them Chastity is; the excess, which resembles the energy as the dropsy to health. ”Neither to moderantism, as Robespierre subordinated it more and more to the Dantonists (Danton supporters) in the sense of a false appeasement and moderation policy, nor to excessive radicalism, as it was for him in the case of the Enragés and the Hébertists , so space could be left if the intentions of the counterrevolutionary European princes were not to be played into the hands of:

- “The foreign courts consult in our administrations and in our section assemblies; they gain access to our clubs. They even have a seat and vote in the sanctuary of the people's assembly. […] If you show weakness, they extol your caution; if you exercise caution, they will blame you for weakness. They call your courage recklessness, your legal sense cruelty. If you give them protection, start conspiracies in front of everyone ... "

The tenor of the speech could easily be understood as follows: "Anyone who deviates from the course of the revolutionary government in any direction is committing high treason".

While the Hébertists attacked the revolutionary government as not being too energetic against revolutionary enemies and in the implementation of sans-culottic economic ideas, Danton's close friend Camille Desmoulins urged in the “Vieux Cordelier” to alleviate the reign of terror by releasing 200,000 suspects and creating a pardon committee; Finally, he also called for the Welfare Committee to be reshuffled. Both opposing factions came from the Cordeliers Club, belonged to the Montagnards or were politically close to them. But that did not protect them from the attack of the revolutionary government. Both the Hébertists and some of Danton's companions, especially Fabre d'Églantine , had made themselves vulnerable through dubious contacts with foreign arms dealers and traders and were suspected of corruption. One by one, they were tried.

Danton himself, on whose initiative the Revolutionary Tribunal had been set up a year earlier, now found himself accused before him. When asked for his address, he said: “My apartment? Until now rue Marat. Soon she will be in nowhere. And then in the pantheon of history. ”Danton's self-defense impressed beyond the walls of the courtroom and threatened to spark a popular uprising. Prosecutor Fouquier-Tinville , who had escaped the trial, obtained a decree from the Convention through the Welfare Committee that enabled Danton to be excluded from the trial for disturbance of public order. The Hébertists came under the guillotine on March 24, 1794, the men around Danton , referred to as "moderates" ( indulgents ), on April 5.

Erosion and the end of the reign of terror

After this double blow against important figures of identification among broad strata of the people, the base of the Montagnards and the revolutionary government under the sans-culottes crumbled more and more, especially since they once again found themselves in an unfavorable economic situation through the establishment of a wage maximum. Robespierre tried to defuse the de-Christianization campaign, which had replaced traditional religion with a cult of reason and revolutionary martyrs, and to render it harmless internally and vis-à-vis abroad by having the convention decree in May 1794: “The French people recognizes the existence of a Supreme Being and the immortality of the soul. ”With a“ Festival of the Supreme Being and Nature ”on June 8th, 1794, Robespierre finally tried to ideologically reconcile and align the nation with a great ceremony and personal direction from Robespierre.

The reign of terror was not relaxed even after the elimination of the Hébertists and Dantonists, on the contrary: two days after the feast of the Supreme Being, the law of the 22nd Prairial was passed, which expanded the circle of potentially suspects again almost at will, by acting as the enemy of the people u. a. should apply “who seeks to spread discouragement with the intention of promoting the undertakings of the tyrants allied against the republic; who spread false news to divide or confuse the people ”.

Before the greatly expanded Revolutionary Tribunal, there were no longer any defense counsel for the accused, but in the event of a guilty verdict there was only one sentence: execution. The phase of the “Grande Terreur” (the “Great Terror”) from June 10 to July 27, 1794, which was initiated by this, led to 1,285 death sentences at the Paris Revolutionary Court alone. By then, the reign of terror had raged even more summarily in the regions of France affected by the civil war. In the punitive actions against Marseille, Lyon, Bordeaux and Nantes, the guillotine, the instrument of individual execution, did not play the main role. In Lyon, the convention commissioners Collot d'Herbois and Fouché practiced mass executions in the fusillage and mitrail shop. Her colleague Carrier also had mass drownings carried out in Nantes in the Loire.