American Revolution

The American Revolution is the name given to the events that led to the separation of the Thirteen Colonies in North America from the British Empire and the independence of the United States of America . The beginning of the revolutionary period is mostly given with the year 1763, when Great Britain began to reform the administration and taxation of its North American colonies after its victory in the French and Indian War, which soon led to protests there. The conflict escalated in the 1770s through to the outbreak of the American War of Independence in 1775 and the formal declaration of independence for the United Stateson July 4, 1776. For the first time in the history of the West, fundamental human rights such as the right to life, freedom and the pursuit of happiness were enshrined in constitutional law. The end of the revolutionary era is often set in 1783, when the British had to recognize the independence of the USA after their defeat in the Peace of Paris . Other historians still count the years until the ratification of the still valid constitution of the United States and the swearing-in of George Washington as first president in 1789.

Origins, long-term causes and history (approx. 1600–1763)

In the early 1760s, the Kingdom of Great Britain ruled a large empire on the North American continent. In addition to the thirteen British colonies, victory in the Seven Years' War had given Britain access to New France and later Canada , Spanish Florida and the Indian territories east of the Mississippi River .

The American colonies before the Seven Years War

Like every significant historical event, the American Revolution was “not a birth out of nothing”, but rather the result of a protracted development that had spanned a period of more than 150 years. Some of the causes and prerequisites of the subsequent development are already rooted in the prehistory, which is why it is also important in the American Revolution to distinguish between acute and long-term latent causes. Even if a detailed narrative of the entire colonial history is not required, the colonial structures and prerequisites are necessary for understanding the American Revolution and therefore indispensable for an analysis of the American Revolution. In the following, therefore, the latent long-term causes are discussed, in which a distinction is made between structures of economic-economic, administrative-political, societal, religious and mental character.

Formation process of the American colonies

In the course of the 17th century, the “colonial-political” interest of European seafarers in the North American continent grew increasingly. While Spain, France and the Netherlands merely established trading bases, England preferred the construction of fortified settlements . The first English pioneers of settlers, who were seafarers, individuals, or religious groups who had been given permission to colonize by royal charter, reached America in the early seventeenth century.

The motivation of the settlers was varied - the reasons for the migration ranged from religious motives to the prospect of free land purchase to the general hope for better living conditions. A distinction is made between motives that gave rise to emigration and reasons that caused immigration ( push-pull model of migration ).

The first settlers, who reached the American continent in 1607 and established the settlement of Jamestown in Virginia , had been moved to immigrate mainly by the prospect of adventure and fortune. Another - extremely well-known - example of the early colonization of America is the religiously motivated immigration of the so-called Pilgrim Fathers , a group of Puritans who repeatedly came into conflict with the hierarchy of the Anglican Church. Instead of establishing a religious freedom state in Virginia, as they intended, their ship, the Mayflower , landed much further north, in what would later become the colony of Massachusetts, in Cape Cod, near what is now Boston. The future action of the settlers was regulated by a contract, the " Mayflower Compact ". At the head of the Plymouth Plantation were church officials elected by the residents. The core of the later American self-image, which includes individual self-determination, democracy, freedom and equality, can already be seen in the church-democratic order of this Puritan community.

Economic conditions

In the course of further waves of immigration, thirteen American colonies emerged in the middle of the 18th century, all of which were under the rule of the British crown. While farm economy prevailed in the north (especially corn and grain), a plantation economy had developed in the southern colonies (preferential cultivation of cotton, indigo, rice and tobacco), to which African-American slaves were drawn (see below). Since the non-continental demand was largely responsible for the sale of the products produced there, it essentially influenced the sales and profits of the southern large landowners (members of the “ planter aristocracy ”, also known as gentlemen farmers (see below)). Therefore, the southern colonies were particularly dependent on the outside world. In the mid-Atlantic colonies there were also several flourishing port cities, especially Boston . Maritime trade was now generally an important economic sector in the New England world .

Already at this time a fundamental difference of opinion between the American colonies and the British motherland can be recognized. Since the English crown saw the colonies mainly as an economic hub and source of raw materials, which should bring their profit and was under their authority, they also saw themselves entitled to levy taxes in the colonies. The Americans, on the other hand, saw the “ Iron Act ” (German: “Iron Law”) of 1750 or the regulations specified in the “ Navigation Acts ” (German: “Navigation Laws”, 1707) as a restriction of their economic freedoms. This economic conflict of interests, which has long smoldered underground, is a major cause of the American independence movement. The financial crisis of the British Crown as a result of the Seven Years' War and the resulting tax laws then led to a further exacerbation of the differences of opinion and the outbreak of the conflict.

Political-Administrative Conditions - The Crisis of the American Ancien Régime

The American people were already relatively heavily involved in colonial administration before the Seven Years' War. In addition to the King employed governors and governor councils existed Unterhäuser ( Lower Houses , called assemblies ) as a self-governing bodies.

Originally, these institutions were only intended to have representative functions, but in reality they gained more and more political power. In a first step, they succeeded in gaining the authority to exercise sole tax control at the financial policy level. This resulted in a financial bond between the royal officials and the Lower Houses . The tax policy proved namely as a very effective means of political pressure, definitely use was made of the in some colonies.

According to Horst Dippel, this "policy of financial pressure" resulted in long-term instability of colonial rule and a crisis in the American Ancien Régime , which went hand in hand with the loss of authority of the English governors. The relationship of political power had shifted more and more in favor of the up-and-coming lower houses, which increasingly gained in self-confidence and saw themselves as “the real administrators” of political affairs. For these reasons, Dippel considers the political structures to be the level that is most important with regard to the subsequent revolution. Self-government in pre-revolutionary times increased political experience, which would later be of advantage, especially for the revolutionary elites.

Social conditions, cultural self-image and regional disparities

Social elites

Within a few decades, the average height of an American was greater than that of a European. In the colonies there was general prosperity and comparatively high wages. So-called gentlemen farmers , wealthy large landowners (see above), formed the top of American society in the south. In Pennsylvania , on the other hand, the proprietary gentry made up the political elite, while in Massachusetts it was lawyers, the so-called lawyers , who formed the social leadership. Nevertheless, the social differences were smaller than in Europe, where the class system divided society into three classes, and were accepted because of the generally good living conditions and the same legal status of the free male population.

slavery

An exception was the legal status of Afro-American slaves, which - due to the fact that they were used almost exclusively as workers on the southern plantations - (in addition to the above-mentioned economic differences between northern, mid-Atlantic and southern plantations) also further increased the regional differences. They were imported from Africa under inhumane conditions to work on the southern plantations - a third perished on the crossing due to lack of space. Her further life and work on the southern plantations took place under similar circumstances. In the process, those without rights had to reckon with discrimination and social exclusion. Children who fathered white colonists with African American women were labeled "colored" and viewed as "racially inferior".

Cultural self-image

According to historian Willi Paul Adams , the residents of the American colonies in London were generally regarded as "second class subjects". The British therefore viewed themselves as being of higher quality. In addition to the American "feeling of inferiority" that resulted, there was also an awareness of superiority, according to Adams: This "superiority complex" stems from the self-confidence that the American colonists acquired through the Calvinist - Puritan - Protestant beliefs and the religious awakening movements of that time.

Religious Developments

The First Great Awakening ( The First Great Awakening , 1730s and 1740s) was the American continuation of earlier religious revivals in Europe and led to the questioning of the authority of existing religious institutions, particularly (but not exclusively) the Church of England . The revival emphasized individual conscience and experience as important sources of religious experience. This included a strong element of the class struggle : God bestowed grace on everyone, regardless of social background or level of education. This was a direct challenge to the upper class view of the superiority of authorities - and a basis for later revolutionary ideas; it was also the first event that streamed through all the colonies as a shared experience, from New England to North Carolina and South Carolina .

In addition, the Puritans saw themselves providentially chosen to build a "new Jerusalem" on the North American continent. The Quaker religious group , which had settled mainly in Pennsylvania, on the other hand, advocated the idea of a "religious minority" refuge based on the idea of tolerance.

Influenced by European ideas of the Enlightenment

The effects of the early scientific revolution had an ever greater impact on everyone's daily life and conscious thinking. The increasing number of publications and the exchange of ideas between like-minded people opened up new areas for questions and reflections. The early works of thinkers like John Locke became the basis for men like Montesquieu . The deist views of some of the founding fathers and their opinions about the appropriate type of government had their roots in the European Enlightenment and became the basis for ideas such as the separation of church and state and other freedoms. The natural law ideas of the Declaration of Independence based for example on John Locke, the separation of powers and the system of checks ( checks and balances ) in the US Constitution, however, go to the state theory of Montesquieu ( The Spirit of Laws ) back. The Enlightenment provided the necessary theoretical basis for the American Revolution. With the American independence movement, however, the theoretical and social ideas of the Enlightenment were also politically realized for the first time.

Initial situation - political and financial circumstances as a result of the Seven Years' War

Financial crisis

Great Britain emerged victorious from the Seven Years' War in the Peace of Paris in 1763 . France had to cede its North American colonies (including Canada) and in return only got the islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe back. Britain had asserted itself in the power struggle for supremacy on the North American continent, but British national debt had reached the alarming level of £ 133 million during the war years . "Interest alone swallowed up over £ 5 million a year".

Pontiac uprising

A war against France's former Indian allies ( Pontiac uprising ) led, if not to conquest, at least to pacification of the western border countries.

British Government ineptitude

In the face of this economic crisis that had arisen from the French and Indian War (as the conflicts of the Seven Years' War that took place on American soil are called) and the Pontiac uprising , economic and political reforms were necessary. The newly crowned King George III. therefore wanted to reorganize his North American possessions together with his Prime Minister Frederick North . To make his empire more stable and profitable, a new economic and land distribution policy was implemented.

The British government, be it the Crown or Parliament, did not recognize many problems early enough. George III was overwhelmed with the political situation in many matters and therefore reacted - like Prime Minister Frederick North or other of his ministers - often too late.

The Road to Rebellion (1763–1773)

Dispute over the land in the west

As a measure of the new land distribution policy, the British Royal Proclamation was issued in 1763. It was intended - ultimately as a late reaction to the Pontiac uprising - primarily to prevent further conflicts between Native Americans ( Indians ) and British settlers. King George III had ordered, without questioning the British Parliament, that resettlement and land acquisition in areas west of the Appalachian Mountains be declared illegal and thus the legal settlement area significantly restricted. The colonies reacted with a wave of indignation: Numerous land speculation societies and especially settlers expressed their displeasure “instead of accepting this approach to the later reserve policy ”. The proclamation, which originally intended to limit the settlement area to the area east of the Appalachian Mountains, de facto became less and less effective. The number of violations probably reached several thousand. Groups of settler pioneers and squatters , for example under Daniel Boone , crossed the proclamation line against the royal will and violently clashed with Shawnee and other peoples who settled in these areas.

Just like the economic reforms, the regulations of the Royal Proclamation did not contribute to an improvement of the situation, but rather aggravated the heated situation.

Economic disputes

Due to the impending bankruptcy, the crown began to take a series of economic steps in 1766 to get more income from the colonies. The requirements were justified by the fact that the colonists were enjoying the benefits of the peace that had been won. Many Americans, on the other hand, were of the opinion that through their engagement in the French and Indian Wars they had sufficiently taken care of the welfare of their mother country.

Theoretically, Great Britain had already regulated the economy of the colonies through the Navigational Act and profited from maritime trade, but an extensive disregard of these laws (so-called benevolent disregard, salutary neglect ) was tolerated for a long time. However, strict enforcement has now become the practice through the use of unlimited search warrants (judicial execution order). In 1761, Massachusetts attorney James Otis Jr. alleged that the executive orders violated constitutional rights. He lost the trial, but John Adams later wrote, "American independence was born there and at that time."

Overview of the pre-revolutionary events

- Previously: Restriction of economic freedoms by the provisions regulated in the Iron Act (1750) and the Navigation Acts (1707), but the actual implementation of the laws is handled with salutary neglect (benevolent neglect )

- 1758: In the colony of Virginia , the Parson's Cause over the remuneration of the Anglican clergy as a result of the Two Penny Acts (1755, 1758) raises fundamental questions about the relationship between the Kingdom of Great Britain and the British colonies.

- 1763: After the successful end of the Seven Years' War, the British crown finds itself in financial difficulties. The American colonies are also said to be involved in paying off the debt burden. The introduction of fees and duties in the colonies follows:

- March 18, 1766: The Stamp Act is repealed as a result of the Stamp Act protests; At the same time, however, the Declaratory Act is passed, which establishes the full right of the British government to levy taxes in the colonies.

- June 2, 1767: Townshend Acts

- March 5, 1770: Boston Massacre

- March 12, 1770: Repeal of the Townshend Acts

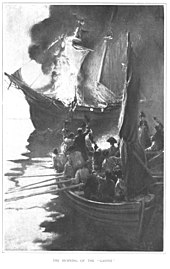

- June 9, 1772: Gaspée affair

- May 10, 1773: Tea Act

- December 16, 1773: Boston Tea Party

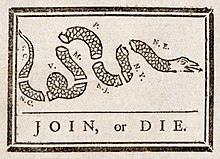

Sugar Act

1764 led Sugar Act (Sugar Act) and Currency Act (Currency Law) of the British Prime Minister George Grenville to economic hardship in the colonies. Protests led to the boycott of British goods and the emergence of the popular slogan No taxation without representation , with which the colonists, citing the colonial founding letters and the Magna Charta, expressed that only their colonial parliaments and not the parliament of the UK could collect taxes from them. Correspondence committees were formed in the colonies to coordinate the resistance. So far the colonies had shown little inclination towards joint action. Grenville's regulations brought them together.

Stamp Act and Declaratory Act

A milestone in the independence movement came in 1765 when Grenville enacted the Stamp Act as a way to finance billeting in North America. The stamp law stipulated that all official documents, commercial contracts, newspapers, brochures and playing cards in the colonies had to be stamped with a tax stamp . This was the first time that there was a direct taxation fee within the colonies, whereas the sugar law that had previously been passed was more like a kind of tariff. The colonial protest now gripped a broad mass. British taxation led to increasing estrangement between the colonies and the mother country. Patriotic groups such as the Sons of Liberty were formed in each colony and openly campaigned to prevent the enforcement of the Stamp Act. As a result of the Virginia Resolution , the turmoil culminated with the Stamp Act Congress , which sent a letter to Parliament in October 1765 as a token of protest. Parliament responded on March 18, 1766 by repealing the Stamp Act, but emphasized its legal authority over the colonies "in all matters" with the included Declaratory Act .

Townshend Acts

The consequences were not long in coming. In 1767, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts , which imposed a tax on some basic necessities imported from the colonies, including glass, paint, lead, paper, leather, ladies' hats, coffee, and tea. The author of the law named after him, Treasurer Charles Townshend , had earmarked part of the tax revenue to finance the soldiers stationed in the American colonies. The colonists should also benefit from their tax payments, for example when securing sections of the settlement border. However, the other part was to be used - to the displeasure of the American patriots - to pay British officials who were in the service of the Crown. Although it was "only" a duty on imported goods, the majority of Whigs did not accept the law because of the second use. The colonial representatives of Massachusetts , James Otis and Samuel Adams , then called for boycotts of British imports in the Massachusetts Circular Letter of February 11, 1768 (Massachusetts Rundbrief). Although the British Colonial Secretary, the Earl of Hillsborough , warned that the local colonial assemblies would all be dissolved if they followed the Massachusetts example, they approved the Massachusetts Circular Letter through written expressions of opinion.

Aggravation of the conflict situation and the Boston massacre

Massachusetts had been the most rebellious of the thirteen American colonies throughout the rebellion. Shortly before 1770 the situation in Boston became more radical : Among other things, the "Liberty", a ship belonging to the colonial trader John Hancock , was suspected of smuggling and confiscated on June 10, 1768 by customs officials in Boston. In addition, the organization of the "Sons of Liberty" received an enormous number of visitors. Angry street protests caused the customs authorities to report to London that Boston was in a state of emergency. In October 1768, two regiments of British troops arrived in Boston, causing tensions to escalate. The development culminated in the Boston massacre on March 5, 1770, when British soldiers of the 29th Regiment of Foot fired into an angry crowd and killed five people. Revolutionary agitators like Samuel Adams used this event to stir up public opposition, but tensions eased after the trial of the soldiers defended by John Adams. The American designation of the events as a massacre has survived to this day.

The Townshend Acts were withdrawn in 1770, and it became theoretically possible that further bloodshed in the colonies could have been prevented. However, the British government had allowed a Townshend law tax to exist as a symbol of its right to tax the colonies - the tea tax. For the independence fighters, who steadfastly upheld the principle that only their colonial representatives could tax them, one tax was too much.

Tea Act, Boston Tea Party, and the start of the revolution

In 1773 the British East India Company , which had had a colonial monopoly for a decade, ran into financial difficulties. The reason for this was also the boycott in the American colonies, which lost an important sales market. Mainly, however, the impending bankruptcy was caused by the increasing territorial gain of the company and the resulting costs. When the company then turned to the British Parliament for financial help, the incumbent ruling Tories party under Prime Minister Lord North drafted a new law.

The then passed Tea Act provided for an amendment to the previously applicable provisions on maritime trade set out in the Navigation Acts: From now on, tea freighters should be allowed to bypass the British Isles and the associated tariffs. Thus a direct, much cheaper import of tea to America was possible. The aim of this regulation was to increase purchasing power in the colonies through the price reduction. It is true that the East India Company tea prices fell so extremely in the colonies that at times the prices of Dutch smuggled goods fell below them; The desired economic upswing did not materialize, however, and the American colonists continued to adhere to their principle of “ no taxation without representation ”.

A tense situation arose in Boston when, in November 1773, the three tea freighters "Dartmouth", "Beavor" and "Eleanor" anchored in Boston harbor. The American patriots, who were represented in the city assembly under Samuel Adams, did everything in their power to prevent the ships from being unloaded. In return, British Governor Thomas Hutchinson did not give in at any price. He issued an ultimatum ordering the captains of the three ships to unload their ships by December 16, 1773. On the evening of December 16, the situation escalated: supporters of the organization of the Sons of Liberty entered the ships in view of the impending unloading and threw tea worth 10,000 pounds, the equivalent of 700,000 euros, into the Boston harbor basin. These events, which would go down in history as the Boston Tea Party, marked the beginning of the American Revolution.

The Beginnings of the American Revolution up to the Declaration of Independence (1774–1776)

Overview of the events from 1774 to 1776

- Spring 1774: The Coercive Acts (so-called Intolerable Acts ) are passed by the British Parliament

- September 5 - October 26, 1774: The First Continental Congress meets in Philadelphia and supports the Suffolk Resolutions which declare the Intolerable Acts unconstitutional, call on the people to form militias , and Massachusetts to form an independent government.

- Joseph Galloway's plan to form a union with Great Britain is rejected.

- April 19, 1775: The battles at Lexington and Concord mark the beginning of the American War of Independence.

- April 19, 1775: The siege of Boston by a gathering of around 15,000 American militia units in front of the city begins

- May 10, 1775: Battle of Ticonderoga , in which the American colonists conquer Fort Ticonderoga in what is now New York State and take its garrison prisoner.

- From May 10, 1775: The Second Continental Congress meets.

- 26 May 1775: official declaration of a state of defense ( English state of defendence ) by the Second Continental Congress

- June 16, 1775: George Washington is appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Colonial Forces

- July 5, 1775: The Olive Branch Petition ( english Olive Branch Petition ) is the last attempt of the Continental Congress to King George III. to appeal to give in to his complaints and prevent further bloodshed. The king isn't even ready to take the petition.

- June 17, 1775: The Battle of Bunker Hill during the Siege of Boston ends in a Pyrrhic victory for the British Army. George III reacts on August 23 with the " Proclamation of Rebellion ".

- June 30, 1775: The Continental Congress passes the " Articles of War ", which contain regulations on how the Continental Army should act.

- July 6, 1775: The " Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms " (German: "Declaration on the necessity and reasons for taking up arms") by John Dickinson is published. It is the only document in the course of the entire War of Independence that can be viewed as a declaration of war.

- from autumn 1775: The invasion of Canada is considered to be the “first definite defeat” of the Continental Army.

- December 22, 1775: The British government passes the Prohibitory Act , which ranks all American ships as hostile. As a result, the Royal Navy can now be used more freely, more freely and more effectively.

- January 10, 1776: The pamphlet " Common Sense ", written by Thomas Paine , which publicly postulates the detachment from the British motherland, is circulated and is widely used.

- March 17, 1776: end of the siege of Boston; British troops leave the city to move to New York. This has resulted in the relocation of the main war events to the mid-Atlantic colonies.

- August 27, 1776: The Battle of Long Island begins the battle for New York, which the British decide for themselves.

- July 4, 1776: The Declaration of Independence , mainly written by Thomas Jefferson , in which the United Colonies proclaim their independence, is ratified by Congress.

- December 26, 1776: In the Battle of Trenton , Washington succeeds in a surprise attack against the Hessian contingents with which the British had increased their troops.

Coercive Acts

As a punitive measure against the Boston Tea Party, the British government under Lord North passed a series of five laws in the spring of 1774, which were intended to send a clear signal against the American resistance movement. Two of the five laws in particular were directed against what was happening in the particularly rebellious colony of Massachusetts:

- With the Boston Port Act. which provided for a closure of the port, the sea trade in Boston was paralyzed.

- The Massachusetts Government Act suppressed the right of assembly of local governments in Massachusetts and with it the individual political self-determination of the colony. At the same time, this law contradicted the freedoms specified in the colonial founding charter.

However, the regulations went beyond a mere response to the Boston resistance:

- The Impartial Administration of Justice Act enabled a transfer of colonial jurisdiction to other courts of the British Empire.

- The Quartering Act said that the American colonists were obliged to provide quarters for British soldiers .

- The Quebec Act struck large parts of the Ohio area of the predominantly French-speaking and Catholic colony of Quebec. He also reintroduced French civil law and stipulated the tolerance of Catholics in this area.

As before, this power failed demonstrative, authoritative and action aimed at the enforcement of one's own opinion among the patriotically minded Americans and rather contributed to the aggravation of the differences between the motherland and the colonies. "Ultimately, the effect was rather the opposite." Soon were the "Coercive Acts" ( English coercive , German:, coercion ') in many colonies, particularly in Massachusetts, as Intolerable Acts (' Unbearable laws') on everyone's lips.

The first continental congress

After initial intra-colonial disputes about the advantages and disadvantages of a joint government instance, "the proponents of a continental congress [finally] prevail". On September 5, 1774, the first meeting of the Continental Congress took place, in which 56 delegates from twelve colonies were represented. Previously, the delegates who were to be sent to Congress had been elected to the colonial Committees of Correspondence. Only Georgia abstained, as the use of the British military in a border conflict with Indians was indispensable. They therefore did not want to anger the mother country by joining a colonial institution whose policy might be directed against Great Britain.

As it turned out, there were two main attitudes to be distinguished in Congress: while the radical colony of Massachusetts advocated a war against the motherland to advance American interests, the southern colonies, which were dependent on British trade for their plantation economy, wanted to proceed much more moderately. At that time, no one publicly expressed a final break with the motherland.

The main success of the first continental congress was a general boycott of British goods. Previously, the delegates had written a declaration of the rights of the American colonies and, in a second step, listed all the violations of the motherland against the postulated rights. The trade should therefore subsequently be stopped until the British Parliament withdrew or at least restricted the Coercive Acts ( article of association ). While imports of British goods were immediately suspended, the Export Cease Act was not due to come into effect until September 10, 1775. In order to actually implement the resolutions, committees of inspection ('inspection committees') were also set up as control bodies.

Before the end of the first continental congress, the delegates made preparations for a second meeting, which was to take place next May (1775). In addition, direct letters were sent to King George III. which most colonists believed was free from guilt. Furthermore, the population was called upon to form militias.

The battles at Lexington and Concord

While there were already obvious military preparations in the American colonies, which the first continental congress had called for, the British government under Lord North continued to stick to its confrontational and authoritarian course. The tensions should now be defused by a series of quick actions (so-called powder alarms ), in which the British militias should disarm the population. Meanwhile, the current Governor of Massachusetts' Thomas Gage , who was also general of the British troops there, received instructions from the British Home Secretary, Earl of Dartmouth , on April 14, 1775, about the American weapons depot in Concord, near Boston, of which he had received information through espionage to evacuate and arrest the rebel leaders there.

The people of Massachusetts had long been waiting for such a military action. In the event of an attack, the Continental Congress had promised them military support for all colonies. At the same time, however, they were obliged to “remain calm and refrain from any action that could be interpreted as aggression”. It was also a symbolic question - after all, it should be the British who provoked the use of violence.

When, on the evening of April 18, 1775, the first British troops under Lieutenant Francis Smith set out from Boston for Concord, the American patriots were prepared for such a situation. The local population was warned at an early stage by the ride of Paul Revere and the lesser-known William Daw .

On the morning of the following day, the British troops faced for the first time in Lexington about 60 Minutemen (militiamen) under the leadership of John Parker , who, however, were more a gathering of farmers and artisans than trained soldiers. During this confrontation, the first shot was fired. To this day, it is not clear which side started the fire first. The fact is that it then came to a fight in which the local militia were defeated and fled. As a result, the British troops destroyed the remains of the weapons cache, which the American colonists had already largely cleared. Another violent confrontation broke out at the North Bridge in Concord , in which the colonists were now in the majority. When the British troops withdrew to Boston, they continued to be ambushed. The battles at Lexington and Concord mark the beginning of the American Revolutionary War.

More military action

Beginning of the siege of Boston

Since the events of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, there had been a siege of Boston by American colonists. The besiegers were a gathering of local militia units of around 15,000 men.

Capture of Fort Ticonderoga

On May 10, 1775, there was another military act by the American colonists in what is now New York State . The Security Committee of the Connecticut Colony had decided to capture the British Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain . When a small force of 200 men set out under the command of Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold, the company's goal was achieved. Through a surprise attack, during which the crew slept, the attackers succeeded in occupying the poorly defended and dilapidated fort. The British crew, less than 60 men, were captured. Through the conquest, the Americans captured large stocks of powder and ammunition, which they used for the siege of Boston.

The Second Continental Congress

As a result of the first fighting, the Second Continental Congress met on May 10, 1775. Although the American colonists viewed the British military actions as "attacks on freedom", detachment from Britain was still inconceivable for most of the delegates. One reason for this attitude was, among other things, the fear of an inversion of the social order.

On 26 May 1775, the Congress officially declared that in the American colonies of the state of defense ( English state of defendence ) rule. In addition, the following month the first preparations for the excavation of a were Continental Army ( English Continental Army ) made. With the appointment of George Washington in mid-June it received a head.

In the autumn of 1775 an administrative revolution took place. The local assemblies that had been formed in most of the colonies were henceforth recognized as legitimate by Congress.

Battle of Bunker Hill

On the night of June 16, 1775, the conflict situation intensified during the siege of Boston, when around 1,500 Americans under the leadership of General Israel Putnam began to climb Breed's Hill in front of the city and the Bunker Hill behind it (German "Bunkerhügel") to build walls that should serve as a defense against the British fleet. Then the British ships opened fire. It was another six hours before the British infantry made a first attack. In another wave of attacks, the American defenders were pushed back.

The battle consequently ended with a British victory, which was bought at a high price: 1054 losses of the regulars were compared to a significantly smaller number of around 450 American patriots. The Battle of Bunker Hill is therefore considered a Pyrrhic victory for the British Army.

Common sense

Thomas Paine , a British customs officer and educated private tutor, had emigrated to America in 1774 at the instigation of Benjamin Franklin . In Philadelphia he quickly became a staunch opponent of slavery and an advocate of American independence. Paine had first addressed the latter publicly in a short article A serious thought , published in October 1775. In January 1776 he then published a much more detailed pamphlet divided into four chapters called Common Sense . In it, Paine stated primarily the necessity of a separation from the motherland. In addition, democratic and natural rights ideas are mentioned.

The publication had far-reaching consequences, as the pamphlet had a huge success - a total of 500,000 copies was reached. The Paines appeal resulted in many changes of opinion in favor of the Whigs. In addition, “Common Sense” produced groundbreaking ideas for the later declaration of independence.

The emergence of the state constitutions

In 1776, the colonies had overthrown their existing governments, closed courts of law, evicted British officials and governors from their homes, and elected congresses and legislatures that existed outside any legal context - new constitutions were badly needed in every colony to replace royal laws.

On January 5, 1776, six months before the Declaration of Independence was signed, New Hampshire ratified the first constitution. In May 1776, Congress voted to suppress all forms of royal authority and replace them with local authority. Virginia , whose convention on June 12, 1776 also passed a fundamental rights declaration mainly formulated by George Mason , the Virginia Declaration of Rights , South Carolina and New Jersey also created their own constitutions before July 4. Rhode Island and Connecticut simply took their existing royal laws and deleted all references to the crown.

Not only did the new states have to decide what form of government they wanted to create, they first had to decide who to choose to create the constitutions and how the resulting document would be ratified. That would only be the beginning of a process that would turn conservatives and radicals against each other in any state. In states where a wealthy active society controlled the process, such as Maryland , Virginia , Delaware , New York, and Massachusetts , the result was a constitution that included:

- solid proof of ownership for a right to vote and even more solid electoral office requirements (only New York and Maryland lowered ownership requirements)

- Bicameral legislature with the House of Lords, which controlled the House of Commons

- strong governors with veto power over the legislature and essential appointments

- little or no restrictions on persons holding multiple positions in government

- Establishment of a state religion

In states where the less affluent were organized enough to have a greater say, particularly in Pennsylvania, New Jersey , New Hampshire, and Vermont, the constitutions resulted in:

- universal suffrage or low ownership requirements to vote or hold an electoral office (New Jersey went so far as to introduce women's suffrage; a radical move it repealed 25 years later.)

- strong unicameral legislature

- relatively weak governors with no veto rights and few appointments

- the ban on holding multiple government offices

- Separation of state and church

Of course, the fact that conservatives or radicals held power in a state did not mean that the less powerful side simply accepted the result. In Pennsylvania, the possessing class was appalled by its new constitution ( Benjamin Rush called it "our state dung cart"), while in Massachusetts voters twice opposed the constitution that had been put forward for ratification; it was finally ratified after the legislature tinkered with the results of the third election. The radical parts of the Pennsylvania Constitution lasted 15 years. In 1790 the Conservatives took power in the state legislature, proclaimed a new constitutional congress and wrote a new constitution that decisively reduced universal suffrage for white men, granted the governor veto and appointment rights, and endowed an upper house with important rights within the unicameral legislature. Thomas Paine called it a constitution unworthy of America.

The United States Declaration of Independence

Emergence

The first suggestions for the official declaration of independence came from Virginia. A provincial congress had formed there, which on May 15, 1776, called on the Virginia envoys represented in the continental congress to “work for independence”. On June 7, the first application for American independence was made by Richard Henry Lee in the continental congress , the was approved on July 2 by twelve votes out of thirteen.

The declaration of independence had been drawn up by a five-member preparatory committee ( English Committee of five ). The definitive design came from Thomas Jefferson , an educated landowner and lawyer from Virginia. In addition to the deletion of an essay critical of slavery and other small changes, the committee adopted the draft text. On July 4th, the Continental Congress unanimously adopted the declaration of independence.

content

In the Declaration of Independence ( English American Declaration of Independence ), the thirteen colonies proclaimed their official separation from the mother country and to form its own sovereign state union the right.

The text of the American Declaration of Independence is clearly structured into several sections: A short introduction (lines 1–3) in which Jefferson explains that the "laws of nature and the God of nature" (line 2) subordinate a people The preamble (lines 4–14), which contains the declaration of general human rights, follows: These include freedom, equality, the right to life and the pursuit of life Happiness. She also demands that governments are to be set up to represent the people, but that if they act unjustly, they can rightly be removed at any time. Thereupon the British king is accused of having acted in exactly the same way (lines 12 f.). Hence, the American colonists would have the right to overthrow the government. This is followed by a long - not always entirely correct - list of detailed examples (lines 15 ff.) Which are intended to substantiate the accusation that the king is an unjust tyrant: These include the accusations that he had armies on American soil without legal consent entertained (see line 24) that he had repeatedly dissolved the chambers of representatives (see line 22) and made judges “dependent on his will” (line 29). Only at the end does the proclamation of the United States of America (lines 77-98) as a free, independent federation of states with all the rights to which it is entitled come, under the invocation of God; that is, the United Colonies were now released from all duties and loyalty to the British Crown and empowered to trade, make alliances and decide about war and peace.

The American colonists have expressed their fundamental concern to form a free, sovereign and independent state. At the same time, however, the declaration of independence is more: for the first time in history, general human rights are postulated. In addition, one can see for the first time that a kind of American identity has developed. But the document also goes beyond the mere proclamation of natural rights (cf. Z. 4–5a), since it employs a contract theory on the legitimation of governments that serve to safeguard natural rights and the right of resistance against unjustly acting representatives of the people. However, the implementation of these political ideas is limited, which is probably due to the fact that the state-theoretical approaches were not in the foreground (after all, the declaration of independence is also not a constitution), but rather served as a cause of indictment against the king. However, when viewed in a historical context, these thoughts are groundbreaking, revolutionary, and subversive, despite their low elaboration. The ideas in the preamble are not entirely new, but they are being used for the first time. It is the American colonists who, with these few sentences, for the first time realize the enlightenment state theory of John Lockes, the philosophy of Charles Montesquieu or the world of thought of Immanuel Kant.

And the Declaration of Independence aptly expresses these ideals through skilful argumentation and a clearly structured structure: by Jefferson first presenting the "truths" that have been identified for him (line 4), and then showing that the British king has suffered "repeated injustices" ( Line 13) has violated this, he succeeds in generating a coherent line of argument. This is evidenced by a detailed list of complaints. Only at the end does Jefferson proclaim the independence of the colonies, the main intention of the document, after he has already set out all the reasons to show that detachment from the motherland is legal. The declaration of independence is also a justification in the political-philosophical sense.

American War of Independence from 1775 to 1783

Overview of the military events 1777–1783

- 5th July 1777: British retake of Fort Ticonderoga

- September 26, 1777: The British succeed in taking Philadelphia , where the delegates of the Continental Congress had previously met.

- The British had previously emerged victorious from the Battle of the Brandywine River on September 11, 1777

- October 17, 1777: As a result of the battles of Saratoga , the English commander-in-chief John Burgoyne is forced to surrender. The conquest of Albany , the original objective of the mission, is not achieved. Instead, the battles of Saratoga are now considered a turning point in the American War of Independence. Part of this battle complex were:

- the Battle of Bennington on August 16, 1777

- the battle at Freeman's Farm on September 19, 1777

- the Battle of Bemis Heights on October 7, 1777

- February 6, 1778: negotiation of a Franco-American alliance; with this, the unrestricted British naval supremacy in the North American territories is gone.

- June 28, 1778: The Battle of Monmouth ends in a tie.

- Autumn 1779: " Southern Strategy "

- December 29, 1778/16. September 10th to October 10th, 1779: In the Battle of Savannah, the British conquer the city in Georgia. An American counterattack in October of the following year fails.

- March 29 to May 12, 1780: In the siege of Charleston (South Carolina), the British succeed in conquering another city, also on

- August 16, 1780 at the Battle of Camden

- Nevertheless, the British do not manage to end the conflict in Carolina. There are guerrilla-like clashes with local militia units.

- September / October 1781: Battle of Yorktown

- September 5, 1781: In the naval battle of Chesapeake Bay , the French fleet under François Joseph Paul de Grasse achieves a victory.

- from September 25, 1781: The French troops under Comte de Rochambeau and the American contingents under George Washington who had arrived from New York begin the siege of Yorktown, where 8,500 British were encircled under the command of Lord Charles Cornwallis .

- October 19, 1781: Signing of the British surrender in Yorktown

- Prime Minister Lord North offers the American colonists the status quo ante , which they reject.

- April 12, 1782: Peace negotiations begin

- September 3, 1783: official end of the war with the signing of the Peace of Paris

America after independence

Overview of the political events 1777–1789

- November 15, 1777: The Articles of Confederation are adopted as a transitional constitution. The first article specifies the name of the federation, the rest regulate the relationship between the federation and the individual states.

- May 1, 1781: The ratification process of the Articles of Confederation is complete. They form the provisionally applicable constitution until 1789.

- Financial crisis in the Atlantic area; incipient inflation in the US

- Winter 1786/87: Shays' Rebellion : Led by Daniel Shays , over 800 smallholders in Massachusetts are rebelling against the debt problem.

- 1785–1795: Northwest Indian War

- May 25, 1787: The Philadelphia Constitutional Convention meets in Philadelphia.

- September 17, 1787: The constitution is passed.

- September 1789: Adoption of the Bill of Rights

- April 30, 1789: George Washington is sworn in as the first President of the United States

- May 29, 1789: With the approval of Rhode Islands , the ratification process ends

As a result of the American War of Independence, in which the colonists had the upper hand militarily, the United Colonies were politically autonomous , but the young nation soon faced new difficulties and tasks. Political reforms regarding the organization as well as a new set of laws and a constitution were necessary. In addition, the intercolonial contradictions made the situation more difficult, and measures that politicians contributed to improving the situation. The national unity that had been created by a common enemy threatened to disintegrate again for a while.

Articles of Confederation

In order to overcome the political void and the fragmentation of the confederation of states, a common constitution had to be created. With this task on June 12, 1776 a committee was assigned to which a representative from each of the thirteen colonies was convened. After a few delays, mainly due to the War of Independence, which was taking place at the same time, the initial drafts by John Dickinson and Benjamin Franklin (and other prominent delegates) were expanded and changed to such an extent that the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union were published on May 15 November 1777 could be finally adopted. While the first article officially laid down the name of the federation, the remaining articles regulated the relationship between the federation and the individual states: In general, most federal elements remained in place, the individual states only had to surrender a few of their rights to the central authority, including the Power to decide on war and peace, the right to conclude a contract with Indians or other negotiating matters. After a ratification process that lasted almost three years, in which all individual states participated, the provisional constitution finally came into force on March 1, 1781. But shortly afterwards, the articles proved to be backward, "in need of reform" and "inadequate."

Financial crisis

As a result of the American War of Independence, the financial crisis in Great Britain, which the Empire suffered after the successful Agrarian Revolution , spread more and more to the entire Atlantic world, to the Caribbean and ultimately to the USA. The United Colonies' finances were exhausted after the War of Independence. As a military winner and economic loser, the young nation found itself in a situation similar to that of the British government in 1763 after the end of the Seven Years' War (see above): The USA, too, had now won the war, but was in a serious economic crisis, which this sometimes resulted in the government having accumulated a considerable mountain of debt during the war years. In addition, there were no economic structures or security measures. Meanwhile, the printing of paper money had further boosted inflation.

New ideas

The American Independence Movement wrote some notable innovations: the separation of church and state , which ended the special privileges of the Anglican Church in the South and the Congregational Church in New England ; a discourse on freedom, personal rights and equality that received a lot of attention in Europe; the idea that government should function on the basis of the consent of the governed (including the right to resist tyranny); the transfer of power through a written constitution; and the idea that the colonial peoples of America could become self-governed nations with their own rights.

The Influence on British North America

For tens of thousands of residents of the Thirteen Colonies , the victory of the independence fighters was followed by exile. About 50,000 United Empire Loyalists fled to the remaining British colonies in North America, for example to Québec, where they settled in the eastern suburbs, to Upper Canada (now Ontario ), as well as to Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia - where their presence established led by New Brunswick . Thus, the seeds were sown for the Franco-English duality in British North America, which might be called the best-known political and cultural characteristic of what would one day become Canada.

Independence Movement Beyond America

The American independence movement was the first wave of the Atlantic Revolutions , as well as the French Revolution , the Haitian Revolution, and Bolívar's War . Aftershocks also occurred in Ireland with the Irish uprising of 1798 , in Poland-Lithuania and the Netherlands .

The independence movement had a strong direct influence in Great Britain, Ireland, the Netherlands and France. Many British and Irish Whigs showed open sympathy for the patriots in America, and the independence movement was instrumental and influential on many European radicals who would later play active roles during the time of the French Revolution.

The American independence movement had an impact on the rest of the world. For the first time in the western world, a people had stripped of the rule of a great power. Enlightenment thinkers had only written about the right of ordinary people to overthrow unjust governments; the American independence movement was the first practical success.

The American independence movement was a desirable model for the peoples of Europe and other parts of the world. It encouraged the peoples to fight for their rights. The American independence movement also encouraged many ordinary people in France. The soldiers in France who supported the insurgents during the American independence movement spread revolutionary ideas. The French people finally rose against the monarchy of Louis XVI in 1789, six years after the Peace of Paris. In the same way, independence movements broke out in the colonies in South America in the early 19th century against occupying Spain. Years later there were similar independence movements in Asia and other parts of the world.

The choice of sides

Patriots, rebels, Whigs

American independence fighters, known as patriots , Whigs, or rebels , had many shades of opinion. Alexander Hamilton , John Jay and George Washington represented a socially conservative faction that later formed in the Federalist Party and was traditionally characterized as careful and concerned about the preservation of the wealth and power of the “better off” in colonial society. Thomas Jefferson , James Madison , Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Paine were commonly portrayed as representing the less affluent side of society and political equality.

Loyalists, King's men, Tories

Large numbers of the American colonists were loyal to the British crown; they were known as Loyalists, Royalists , Tories, or King's Men. The loyalists often belonged to the same affluent social circles that formed the right wing of the patriots (such as Thomas Hutchinson ); apart from that, the Scottish highlanders of the Mohawk Valley or the borderlanders of Georgia included a great many poor King's Men. Some loyalists were Indians, such as Joseph Brant , who led a mixed group of Indians, white settlers and white workers for the loyalist side. After the war, the United Empire Loyalists became a central part of the Abaco Islands ( Bahamas ) population , the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Ontario, and Freetown in Sierra Leone .

Contemporary patriot Benjamin Franklin believed a third of American colonists were loyalists. Today's historical research suggests, however, that about a fifth of all Americans were on the royal side.

Whigs and Tories

The names of the American patriots as "Whigs" and the colonial loyalists as "Tories" have their origins in the history of England : As early as the first half of the 17th century, differences of opinion had begun in the English parliament. The political groupings that had formed through the union of the bearers of the respective views, however, did not yet have the character of a party. Only in the phase up to the outbreak of the Glorious Revolution of 1688/89 did the differences and contradictions intensify, so that two factions emerged that were fundamentally different from each other, even opposing each other: While the Whigs were Jacob II , the brother of the then reigning King Charles II tried to exclude them from the line of succession because of his Roman Catholic faith, the Tories rejected such considerations. During the reign of Charles II, the two terms came up: Originally used as political propaganda and insulting the opposing side (abbreviated for English Whiggamore , German “cattle driver”), the term “Whig” was first used around 1679. The etymological origin of the term "Tory" also comes from these years.

In the decades that followed, after the Tories had approached the Whigs in the Glorious Revolution, there was a slight change in the meaning of the terms: The Tories now embodied a conservative attitude in general, whereas the Whigs were particularly considered to be economic liberalists. Thus the latter also represented the attitude of the colonies. This caused the large number of American colonists to "identify with this party". The terms were transferred to the American area, which was also connected with a change in meaning: While the patriotic colonists were soon known as Whigs, the royalists were known as Tories called. The reason for the takeover in the American area was primarily "rhetorical in nature".

Class differences between the patriots

Just as there were rich and poor loyalists, there were also rich and poor patriots with different goals for the independence movement. Wealthy patriots understood independence, their exemption from British taxes and restrictions on conquering the country in the west, but were keen to gain control of the emerging nation. Many artisans, small traders and small farmers, on the other hand, sought independence in the sense of a reduction in the power and privileges of the elite. The rich patriots needed the support of the lower classes but were afraid of their more radical goals. John Adams (an elite but more educated than rich) attacked Thomas Paine's "Common Sense" for the "absurd democratic notions" it proposed.

Women and the independence movement

Role in boycott and protests against British taxation

The boycott of British goods would never have worked without the willingness of American women to participate: women did most of the home shopping and the boycotted goods were largely household goods such as tea and clothing. And since clothing is a basic necessity, women returned to spinning and weaving - jobs that had not been needed for a long time (so-called “homespun” goods). In 1769, Boston women were making 40,000 spindles of yarn, and 180 women in Middletown, Massachusetts were weaving 20,522 yards of clothing.

As the independence movement advanced and economic divisions deepened, women were often directly involved in protests. Among other things, they took part in hunger riots and tars and feathers , which was the response of the people to the price gouging of loyal and patriotic traders. On July 24th, 1777 z. B. Thomas Boyleston, a patriotic trader who withheld coffee and sugar to wait for price increases, versus a crowd of 100 or more women who took keys to his warehouse and distributed the coffee themselves while a large group of men stood by and looked on, amazed and speechless.

Although the regulations of the Stamp Act tended to affect the male population, some women also wanted to show their displeasure with the 1765 law by holding public rallies.

With the departure of the Townshend Duties , the role of women expanded. They often took on the task of replacing the many boycotted goods - as far as possible - with products they had developed themselves.

In October 1775, as a result of the establishment of the Continental Congress, 51 women met in Ederton for a congress. Abigail Adams , the wife of John Adams, was one of the most politically active women in the American independence movement. This is evidenced by the intensive correspondence with her husband, who was a delegate at the Continental Congress. The writer Mercy Otis Warren also represented an anti-British position in her works. Despite these protagonists, American women were not granted universal suffrage until 1919.

Importance of women in the war of independence

During the War of Independence, because men were called up, it was mainly women who took responsibility for property and the remainder of the family. In doing so, they had to reckon with looting from the opposing side or the like - especially in border areas. In addition, there was often a psychological burden that resulted from the absence of the husband or sons in the war. Other women from financially disadvantaged backgrounds followed their husbands in the army, where they served as cooks or laundresses. Women who chose this path are known as " camp followers ".

consequences

Even if the American Revolution did not result in political equality, it nonetheless brought about changes in relation to the social role of women in private life: the previous image of women focused on family responsibilities, which primarily included bringing up children and the household belonged, limited, the “new understanding of roles” also envisaged women as “guardians of virtue” ( Republican Motherhood ). Accordingly, women should have an education to enable their children to be raised in a morally good manner. As a result, women learned Latin and Greek to a greater extent, or occupied themselves with history and literature. However, direct interference in political affairs was still prohibited.

Containment and definition of the revolution

To this day, the question of whether the independence movement, the war against the motherland and the founding of the USA, can be described as a "revolution" is controversial in historiography outside of the English-speaking world. Even a differentiated view of the events is difficult, especially since different concepts and definitions of the revolution are the basis.

However, the majority of today's research supports the hypothesis that the independence movement was of a revolutionary character and could therefore be described as a revolution.

Revolution concept and understanding of revolution

In general, there is agreement that the term revolution “in political and sociological parlance” denotes a lasting and profound change in “social and political structures”, which may be associated with an upheaval in the “system of cultural norms in a society”; It is also widely recognized that violence, although armed conflict did occur in most of the great examples of the revolution in history, is not a constitutive feature of the phenomenon.

However, there is still no clear definition of the extent and speed of a revolution. According to the historian Horst Dippel , the understanding of revolution is at the same time tied to the respective time, which resulted in “new interpretations of the phenomenon of 'revolution'”: For example, political liberalism of the sixties “divided the phenomenon of 'revolution' into 'good' 'and' bad 'revolutions propagated ”, a view that is generally rejected today. A uniform historiography is therefore hardly possible.

Social aspect

Most striking are the deviations from a Marxist-dialectical view of the revolution, which tries to describe the events in America with historical materialism . To interpret the events, the theory of Karl Marx is used, which sees the causes of revolutions in the economic and social crises of a social level and the resulting intensified class struggle . However, with the exception of slavery, there was in fact no relatively strong oppression of the population in the colonies and thus no prerequisites for class struggle. Rather, the population enjoyed great economic freedom. There was no class society as there was in Europe before the outbreak of the French Revolution , nor was there a numerically large peasant class. The population was not exposed to any existential crisis. The colonial taxes and repression did not result in a financial or social crisis either. The founding of the USA and the constitution did not result in an immediate “crumbling of the social society pyramid”. Since there have been no immediate fundamental changes and upheavals in the structure of society, the American independence movement does not agree with the theory of stages of development. From the perspective of historical materialism, the American independence movement is not a socio-political society revolution.

Nevertheless, according to the historian Jürgen Heideking, the American events brought about a change in social conditions: 50 percent of the upper class had been replaced and over 70 percent of the colonial incumbents had lost their jobs. In addition, according to Heideking, the independence movement is said to have finally shattered the mentality of the “still quite effective monarchical-class structure” and triggered a veritable “crisis of authority”.

"Outward Revolution"

There are also some deviations from a more general concept of revolution. The cause of the independence movement had mainly been the conflict between the American colonies and their mother country Great Britain. Many of the later advocates of American independence originally intended only to assert their accustomed rights against the Crown, which were secured by parliament in Great Britain. The UK taxes, duties and charges were no longer accepted. There were both commercial reasons - such as the demand for exemption from the tax burden - as well as non-material reasons - compare the saying “No taxes without representation” - reasons to separate from the mother country and to want to unite to form a political unit of their own. In this perspective, the independence movement and the war are viewed as a national question that can be viewed as an "outward revolution", since independence should not completely overturn the existing order, but rather continue it through a self-determined order.

Political aspect

As for the fundamental upheaval at the political level, the American independence movement largely lives up to this revolutionary criterion. The historian Hans Christoph Schröder wrote about the American Revolution in 1982: "[T] he comprehensive understanding of the revolutionary character of the events in America and of their significance in world history can only be obtained if one understands them as a constitutional revolution." ()

After the end of the war of independence, a democratic, sovereign republic, detached from the motherland, actually emerged. In particular, the state constitutions reflected the revolutionary, new and revolutionary ideas: These include the general human rights formulated for the first time in the Declaration of Independence, including the right to life, freedom, the pursuit of happiness and the demand that “all people are created equal”. However, the achievements of the American Revolution go beyond this natural legal framework - the Declaration of Independence of 1776 also established a contract theory about the legitimacy of governments that serve to safeguard natural rights and about the right of the people to resist unjustly acting governments. In the constitution of 1789, the principle of popular sovereignty, parliamentarism, the separation of powers and mutual control, a representative system and individual self-determination were politically anchored. This was the first time in the history of modern times that the enlightenment ideas of Immanuel Kant , the state-theoretical approaches of Charles Montesquieu and the natural rights postulated by John Locke were put into practice.

A contradiction to the formulated principle of equality, however, was the discrimination against minorities, the Native Americans who were victims of the Frontier movement, on the one hand, and the African-Americans who were abused as slaves on the other. In addition, women were excluded from political life. However, this does not change the fact that the political order has been turned upside down from the ground up. The break with previous social principles lies in the constitution and the independence movement. The results and the future significance of the state system clearly show that the outcome of the independence movement was revolutionary and modern.

In his lectures to King Maximilian of Bavaria in 1854, Leopold von Ranke expressed this view when he said:

“This was a bigger revolution than any before in the world, it was a complete reversal of the principle. It used to be the king by the grace of God around whom everything was grouped; now the idea emerged that violence must rise from below. [...] These two principles face each other like two worlds, and the modern world moves in nothing but the conflict between these two. "

History of Historiography

The decisive beginning of the history of the American Revolution was the publication of the two-volume History of the American Revolution in 1789, a work by the American doctor and historian David Ramsay , at a time when the enthusiasm for the preceding events was still great and the American Revolution therefore was celebrated enthusiastically. Ramsay, who had seen the independence movement first hand and was even a member of the South Carolina legislature , described the revolution in the spirit of American patriotism by portraying it as “the heroic, downright superhuman”. Parson Weem's Life of George Washington is an equally uncritical work that put the nation's birth in an exclusively positive light .

Not so Mercy Otis Warren's three-volume work History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution (1805), which covered the entire history of the American Revolution from the Stamp Act to the ratification of the constitution: According to Horst Dippel, the actual content of these works is rather "The increasing domestic political controversy between the federalists around Alexander Hamilton [and the author's husband] John Adams " "and the Republicans around Thomas Jefferson on the dispute over the interpretation and preservation of the revolutionary heritage and the founding principles of the Union". In any case, the author also brought controversial ideas into her work. Such "disputes about the right interpretation and its meaning for one's own time" determined - in the course of an increasing scientificization of the debates - the reception of the further decades up to the outbreak of the Civil War .

It was not until George Bancroft succeeded in publishing his twelve-volume History of the United States, from the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston 1834-1882), which soon became a standard work of American historiography, to end the existing controversies and set a new era in To ring in reception history by interpreting the American Revolution as a sign of the “unstoppable triumphal march of democracy in the world”.

See also

literature

Primary literature

- William Bell Clark et al. (Ed.): Naval Documents of The American Revolution . Washington 1964–2005, 11 volumes. ( Digital copies )

- Willi Paul Adams, and Angela Meurer Adams (eds.): The American Revolution in Eyewitness Reports. dtv, Munich 1976.

- Bernard Bailyn : Pamphlets of the American Revolution, 1750-1776. Volume I. Cambridge (Massachusetts) 1965.

- Worthington Chauncey Ford: Journals of the Continental Congress 1774–1789. 34 volumes, 1904–1937. Reprinted New York 1968.

Secondary literature

- Overall presentation

- Horst Dippel: The American Revolution 1763–1787. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-518-11263-5 .

- David Hawke: The Colonial Experience. Bobbs-Merrill, 1966, ISBN 0-02-351830-8 .

- Michael Hochgeschwender : The American Revolution. Birth of a Nation 1763–1815. CH Beck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-65442-8 .

- Frances H. Kennedy (Ed.): The American Revolution: A Historical Guidebook. Oxford University Press, New York 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-932422-4 .

- Charlotte A. Lerg: The American Revolution. UTB, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8252-3405-8 .

- Robert Middlekauff : The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789 , Oxford History of the United States, Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Edmund S. Morgan : The Birth of the Republic, 1763-89. 3rd revised edition. University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- Gary B. Nash: The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America. Viking, 2005, ISBN 0-670-03420-7 .

- Hans-Christoph Schröder: The American Revolution. Beck, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-406-08603-9 .

- Hermann Wellenreuther: From chaos and war to order and peace. The American Revolution Part One, 1775–1783. LIT, Münster 2006, ISBN 3-8258-4443-9 . (= History of North America in an Atlantic perspective from the beginning to the present. Volume 3)

- Howard Zinn: A History of the American People . Volume 2: Declaration of Independence, Revolution and the Rebellion of Women. Black Friday, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-937623-52-8 .

- Presentation of political ideas and constitutional history

- Willi Paul Adams : The American Revolution and the Constitution 1754–1791 . Creation of the American Federal Constitution. Edited with Angela Adams. dtv documents, Munich 1987.

- Willi Paul Adams: Republican Constitution and Civil Liberty . The constitutions and political ideas of the American Revolution. 1763-1787. Neuwied 1973, ISBN 978-3-472-74537-2 .

- Bernard Bailyn: The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Harvard University Press, 1967, ISBN 0-674-44301-2 .

- Jürgen Heideking: The loosening of ties: The formulation of the declaration of independence and the constitution. In: Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius (ed.): DIE ZEIT World and cultural history in 20 volumes. Volume 10, pp. 492-504.

- Dick Howard: The Foundation of American Democracy. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2000.

- Dominik Nagl: No Part of the Mother Country, But Distinct Dominions. Legal Transfer, State Formation, and Governance in England, Massachusetts, and South Carolina, 1630-1769. LIT 2013, ISBN 978-3-643-11817-2 . on-line

- Dimitris Michalopoulos, America, Russia, and the Birth of Modern Greece. Academica Press, Washington / London 2020, ISBN 9781680539424 .

- Gordon S. Wood : The Creation of the American Republic. University of North Carolina Press 1969.

- Gordon S. Wood: The Radicalism of the American Revolution. Alfred A. Knopf 1992.

- Social history

- Carol Berkin: Revolutionary Mothers. Women in the struggle for American Independence. New York, vintage 2005.

- David Brion Davis: The Problem of Slavery in the Age of the Revolution. Cornell University Press, Ithaca 1975.

- Christian Gerlach: Elite Interests and Social Conflicts in the American Revolution. A sociological consideration. Vdm Verlag Dr. Müller, 2008, ISBN 978-3-8364-5901-3 .

- James O. Horton, Lois E. Horton: Slavery and the Making of America. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005.

- Military history and war of independence

- Jürgen Heideking: Victorious rebels: The War of Independence In: Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius (Hrsg.): DIE ZEIT. World and cultural history in 20 volumes. Volume 10, Biographisches Institut, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-411-17600-7 , pp. 505-512.

- Causes, origins and history

- Frank Kelleter: American Enlightenment: Languages of Rationality in the Age of Revolution. Schöningh, 2002, ISBN 3-506-74416-X .

- John C. Miller: Origins of the American Revolution. Little, Brown, 1943. (Reprint: Stanford University Press, 1974, ISBN 0-8047-0593-3 ; 1991, ISBN 0-8047-0594-1 )

- Gary B. Nash: The Urban Crucible: The Northern Seaports and the Origins of the American Revolution. Harvard University Press, 1986, ISBN 0-674-93059-2 .

- Media history

- Frank Becker : The American Revolution as a European media event. In: European History Online . Published by the Institute for European History (Mainz) , 2011, accessed on: August 25, 2011.

- Beginnings

- Jürgen Heideking : The Pursuit of Happiness: The American Revolution. In: Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius (ed.): DIE ZEIT World and cultural history in 20 volumes. Volume 10, pp. 490-492.

- Comparative consideration of the revolution

- Hannah Arendt : About the Revolution ( On Revolution New York 1963). 4th edition. Piper, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-492-21746-X .

Web links

- Literature on the American Revolution in the catalog of the German National Library

- The American Independence Movement at americanrevolution.com - historical information, documents, images and more

Remarks

- ↑ Horst Dippel: The American Revolution 1763-1787 . 1985, p. 18 .

- ↑ a b c Cf. Horst Dippel: The American Revolution 1763–1787 . 1985, p. 18 .

- ↑ "Those Puritans who sailed to America as so-called pilgrim fathers on board the Mayflower and went ashore at Cape Cod in what is now Massachusetts at the end of 1620" (Horst Dippel: Geschichte Der USA . 9th edition. CH Beck, 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60166-8 . )

- ↑ a b c Horst Dippel: The American Revolution 1763–1787. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1985, p. 27.

- ↑ a b cf. Horst Dippel: The American Revolution 1763–1787 . 1985, p. 31 .

- ↑ a b Horst Dippel: The American Revolution 1763–1787 . 1985, p. 30 .