Boston Tea Party

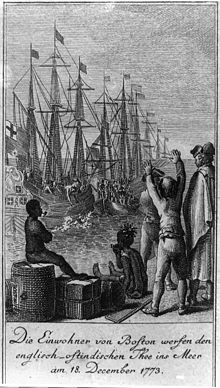

Boston Tea Party is the name of an act of resistance against British colonial policy in the port of the North American city of Boston on December 16, 1773. On that day, Boston citizens , symbolically disguised as Indians , broke into the port and threw three loads of tea (342 boxes) the British East India Company from there anchored ships into the harbor basin . It is difficult to reconstruct who the active activists in disguise actually were, but they probably represented a broad spectrum of Boston society, including some farmers from the surrounding villages.

prehistory

The tax and customs dispute

The Boston Tea Party was the culmination of a long simmering dispute between the 13 North American colonies and motherland Great Britain .

The Seven Years' War in Europe (1756–1763) and the French and Indian War in North America (1754–1763) had a heavy burden on the British treasury. The crown's debts had nearly doubled in a few years and stood at £ 132 million in 1763. In addition, the costs that the colonies directly caused increased. After the end of the war, the British King George III. Have colonies and Indian territories separated by his proclamation of 1763 . In the following time, conflicts arose again and again, as the settlers wanted to claim further areas on the Ohio River , which belonged to the Indian territories, despite the ban . Only by stationing additional troops could the outbreak of a military conflict between settlers and Indians be prevented.

In view of the high national debt, the parliament in London saw it as justified that the colonists contributed at least part of the maintenance of the troops sent to their protection. The laws enacted for this purpose such as the Sugar Act of 1764 or the Stamp Act of 1765 meant a rather mild taxation of the colonists, which was well below the average burden of the subjects in the motherland. There the tax burden was almost fifty times higher.

Nevertheless, the tax policy measures met with some bitter resistance in North America. As British citizens, the colonists were entitled to vote, but were in fact unable to exercise this right because of the great distance. Colonial leaders therefore argued that the London Parliament could not levy direct taxes in North America if the colonists were not represented in it. This attitude is summed up with the slogan "no taxation without representation" ( " no taxation without representation together"). British constitutional lawyers disagreed with the thesis that the representation of the colonies takes place indirectly through the bodies represented in parliament such as the nobility, cities, clergy and common people.

A serious constitutional conflict arose from these two positions, in which the individual understanding of representation that dominated the colonies clashed with the corporate ideas in Great Britain. However, this did not imply a break between the colonies and the motherland. On the contrary, the colonists continued to see themselves as British citizens who could invoke traditional civil liberties, as they had developed in the English legal tradition with an unwritten constitution . Until the escalation of the crisis in relation to the mother country in 1775/1776, there were only isolated calls for independence from Great Britain and for the establishment of a separate legal system .

The British Parliament did not recognize the attitude of the colonies and insisted on its sovereign right to tax. Despite this, Treasury Secretary Charles Townshend finally tried to defuse the conflict. Direct taxes - the most famous of which is stamp duty - were repealed and replaced by "external taxation" through customs duties. The Townshend Act placed tariffs on imports of leather, paper and tea into North America from June 29, 1767.

The colonists reacted violently to these tariffs. A group of men willing to resist, called the Sons of Liberty , called for boycotts . On March 5, 1770, there was a bloody clash of colonists in Boston with British forces of order who had been stationed in the city to guarantee the collection of the Townshend tariffs. In what became known as the Boston Massacre , five people died.

From a purely fiscal point of view , the North American import tariffs made little sense from the start. In London it was calculated that only the tea tariff would generate significant income. Even that turned out to be a milkmaid bill , as British tea sales in North America fell sharply because of the resulting boycotts and smuggling of tea from the Netherlands Antilles . The British East India Company , which had a monopoly on trade with the colonies, now imported less tea to Great Britain, where the goods were temporarily stored in London warehouses for later circumnavigation to the colonies. As a result, the krona lost a significant amount of income from British import tariffs that were even higher than the Townshend tariffs. On balance, this resulted in a loss of income for the tax authorities, which further exacerbated the financial misery.

Under the new Prime Minister Lord North , the North American import tariffs were largely abolished in 1770. The tea tariff was excluded from this. This shows that the British government was now less concerned with improving the budget than with the principle. While the boycotts of the other goods practically ended, the colonists continued to buy mostly smuggled Dutch tea.

The Tea Act of May 10, 1773

The East India Company soon became troubled when the North American market largely disappeared. Tons of unsold tea were rotting in their London warehouses. However, the British government could not afford the threatened bankruptcy of the company, also because it supported the British colonial troops in India from its own resources .

To avert the ruin of the East India Company, the British Parliament passed the Tea Act in May 1773 at the instigation of Prime Minister Lord North . His aim was to lower the final price, which should stimulate the sale of tea in the colonies again and thus increase the profits of the East India Company. Strangely enough, however, it was not possible to agree on the simplest way to achieve this goal, namely a lifting of the North American import tariffs, which were the real cause of the misery. Instead, the duties to be paid by the East India Company on imports into England were removed. In addition, the company was now given greater autonomy in handling its trade and could, for example, dispense with American middlemen to sell their tea.

In relation to the North American colonies, the Tea Act led to a decisive escalation. The East India Company would now have been able to lower the final price of the tea, which is still burdened by the North American import tariffs, so much that it could even have been sold cheaper in the colonies than the widespread Dutch smuggled tea.

The colonists recognized in the Tea Act an attempt by the British government to undermine the boycott movement against the tariffs, which were regarded as unjustified, and to drive a wedge between the colonists who were guided by more principled and more economic considerations. In addition, influential North American middlemen saw their interests violated. The possibility of direct final sale by the East India Company enshrined in the Tea Act would have made the intermediate trade superfluous. It became apparent that the company would also establish a trade monopoly in the North American colonies. Finally, the colonists feared that expected additional revenue for the crown from import taxes could be used to finance institutions of the royal governors. This in turn seemed to threaten the colonists' self-government by their own parliamentary assemblies.

The interests of the American tea importers and traders on the one hand and the Sons of Liberty on the other now coincided. Both groups decided to prevent the East India Company from landing and selling the cheaper tea at all costs. A first step in this was the coordinated appeals between the colonies to the captains of pilot ships not to navigate ships loaded with British tea into the ports. These appeals were largely successful.

The course of the Boston Tea Party

A special situation arose in Boston, where on November 28, 1773 the Dartmouth anchored. It was the first of four ships laden with cheap tea that the East India Company had dispatched to Massachusetts. Boston opponents of the Crown, such as John Hancock , who himself made considerable money smuggling Dutch tea, and Samuel Adams were determined to stop the tea being unloaded at all costs. They also used threats against the captain, crew and dock workers.

Governor Thomas Hutchinson said the Dartmouth has been under the jurisdiction of the Boston Customs House since entering the port. He forbade Captain Francis Rotch , who as co-owner of the ship wanted a peaceful solution to the conflict, to sail again without paying the import duties incurred. Hutchinson instructed the Royal Navy to forcibly prevent the Dartmouth from leaving port if necessary. He also announced that the tea would be forcibly extinguished and sold if the taxes were not paid within three weeks. Private motives also played a role in Hutchinson's strict position, since two of his sons had a business interest in selling the tea as agents for the East India Company.

The situation escalated on the evening of December 16, 1773, shortly before Hutchinson's ultimatum expired . At a gathering of the Sons of Liberty in the Old South Meeting House , Samuel Adams cheered those present by pointing out that the tea would be unloaded from Dartmouth in a few hours' time . The meeting then sent Captain Rotch to Governor Hutchinson with a final petition. It repeated the demand that the Dartmouth and the two ships Eleanor and Beaver, which had meanwhile arrived, be allowed to sail again without unloading the tea and paying the customs duties. Hutchinson rejected the petition.

When Rotch announced this to the people gathered in the Meeting House , around 50 participants at the meeting ran to the harbor to howl of war. The majority of them had "disguised" themselves as Mohawk Indians in protest against the colonial government . Arrived at the port, the men stormed the ships in three groups and poured the entire cargo of 45 tons of tea into the water. The spectacular action, which lasted several hours, was completely non-violent. Thousands of spectators watched the nocturnal hustle and bustle from the bank without intervening. Although they supported the Mohawks' approach, there were few cheers. Attempts by individuals present to mingle with the men on the ships and put tea leaves in their pockets for private consumption were prevented.

At the end of the operation, the men cleaned the ships and even apologized to the harbor guards for a broken lock. The overall extremely disciplined process speaks for their careful planning. In fact, destruction of the tea had already been suggested several times from the crowd at the town councils held in the weeks before. However, initially only one of the leading men of the Sons of Liberty had adopted the demand.

John Adams notes in his diary about the events of December 16, 1773 :

“Last night three loads of Bohea tea were poured into the sea. A warship set sail this morning .

This is the greatest move yet. This last venture by the patriots has a dignity […] that I admire. The people should never rise without doing something memorable - something remarkable and sensational. The destruction of tea is such a bold, determined, fearless and uncompromising act, and it will necessarily have such important and lasting consequences that I must consider it an epoch-making event. "

The secretary of St. Andrews Lodge , which worked in the Green Dragon Tavern , stated on the evening of December 16, 1773 that the lodge had adjourned its meeting until the following evening, and wrote a capital “T ".

The meaning of the Indian disguise

Historians have long failed to give a convincing answer to the question of why the Indian disguise was chosen for the protest at the "Boston Tea Party". It was traditionally assumed that the identity of the people involved in the action should be concealed or that the Mohawks should be blamed. The disguise, however, was predominantly symbolic and consisted mainly of a feather attached to the hat, a face painted black, a simple cover and an ax that was redeclared as a " tomahawk " and was carried along. Some of those involved weren't even disguised at all. Contemporary and later illustrations, which ascribe the men a completely “Indian” appearance, including a bare torso and loincloth, are not sufficient evidence (not least because the Boston Tea Party took place on a cold December night). Apart from their appearance, the participants underlined their "Indian nature" by communicating with one another in pseudo-Indian pidgin English .

More recent works point to a more plausible background to the masquerade: As victims of sharp repression by the British authorities and the army (in which the colonists certainly participated in full), the Indians, according to these representations, have stood for the since the beginning of the protest movement in the 1760s Oppression of the colonies by the British Parliament and His Majesty's Government. At the same time, they symbolized a newly developing American identity that set itself apart from its European origins and, in particular, included freedom from traditional laws and class boundaries.

In the Boston case the element of a decided resistance stance with asymmetrical warfare was added, in which the 'underdog', however, was to have the upper hand in the end. In connection with the protests against the British tariffs, however, there was a special association of the Indians with tea: Boycott proponents had for several years propagated a tea as an alternative to imports by the East India Company, which was brewed from a Porst variety growing in New England and used it as the only real “Indian tea” (means both “Indian tea” and “Indian tea”).

The disguise at the Boston Tea Party was only the most famous case of a practice of linking the ideals of freedom with the symbol of the Indian, which was found again and again in the American Revolution and later national history. The historian Philip J. Deloria sums up: “The playing out of Indian Americanism provided a powerful basis for subsequent endeavors for a national identity. [...] 'Indian game' has become an enduring tradition in American culture that continues from the moment of the national big bang to the ever expanding present and future. "

Follow and reception

In the months after the Boston Tea Party, there were a number of other actions against alleged distributors of British tea in the North American colonies. Wandering traders were repeatedly forced to burn their goods. In Weston , Massachusetts, an inn was demolished by a squad of citizens disguised as Indians after rumors spread that the owner was selling Bohea tea to the East India Company. In larger cities, citizens gathered to publicly burn their private tea supplies at stake. They swore vows against further consumption of the drink. Articles appeared in newspapers claiming that bohea tea was harmful to health. The official, customs-relevant import of tea into the American colonies fell from the already low level of 1773 by over 90% in the following twelve months.

The British government refused to accept the provocation of the tea parties and other resistance actions. Prime Minister Lord North said that only "New England fanatics" could imagine they were being suppressed by cheaper tea. In Parliament in London there was a call for punitive action against Boston; even the destruction of the city was proposed. Edmund Burke , the eminent state theorist and debater, stood in isolation with his appeal for moderation and the demand for a concession to the colonies to be allowed to tax themselves.

Lord North's government enacted a series of laws that came to be known as the Intolerable Acts . These included closing the port of Boston on June 1, 1774 and restricting the freedoms of the colonies, particularly those of Massachusetts. The representatives from twelve colonies then met from September 5 to October 26, 1774 in Philadelphia for the first continental congress . This recommended that a separate militia, the Continental Army, be formed and that economic sanctions be imposed on Great Britain. The further escalation of the conflict led from April 1775 to the outbreak of the American War of Independence .

The "Boston Tea Party" is also the subject of the novel Johnny Tremain. A novel for old and young (Johnny Tremain. A Novel for Old and Young) by Esther Forbes , which was filmed in 1957 by Robert Stevenson for Walt Disney .

Musician Alex Harvey dedicated a song to the event that was listed in the UK's top 15 in 1976.

The conservative American tea party movement , which campaigns against tax increases, among other things, has also named itself after the Boston Tea Party.

Boston Tea Time

Three years after the Boston Tea Party in 1773, the custom of holding a tea hour on the afternoon of December 16, Boston Tea Time , became established. Due to the United States' Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, the population gained a new American identity. In their new self-confidence, they caricature the British way of life. Great importance is attached to afternoon tea in particular, which follows certain rules. This British tea culture is mockingly imitated by the residents of Boston every year. In the last century, however, the custom has been practiced less and less and is gradually becoming less important.

literature

- Benjamin L. Carp: Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America. Yale University Press, New Haven 2011, ISBN 978-0-300-17812-8 .

- Philip J. Deloria: Playing Indian. Yale University Press, New Haven et al. 1998, ISBN 0-300-07111-6 (also: New Haven CT, Yale University, dissertation, 1994).

- Bruce E. Johansen: Mohawks, Axes and Taxes: Images of the American Revolution. In: History Today. Vol. 35, No. 4, April 1985, ISSN 0018-2753 , pp. 10-16.

- Benjamin Woods Labaree: The Boston Tea Party. Oxford University Press, New York NY 1964.

Individual evidence

- ^ Robert Middlekauff: The Glorious Cause. The American Revolution, 1763–1789 (= The Oxford History of the United States. Vol. 3). Revised and expanded edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford et al. 2005, ISBN 0-19-516247-1 , p. 232.

- ↑ cf. z. B. Bill Bryson : Made in America. Black Swan, London 1998, ISBN 0-552-99805-2 , p. 38.

- ↑ Eugen Lennhoff, Oskar Posner, Dieter A. Binder: Internationales Freemaurerlexikon. 5th, revised and expanded new edition. Herbig, Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-7766-2478-6 , p. 148: Boston Tea Party .

- ^ Philip J. Deloria: Playing Indian. 1998, p. 7. (translated from English).

- ↑ Christoph Harsen: General Education: Massachusetts , March, 2010.

- ↑ Harlow Giles Unger: American Tempest. How the Boston Tea Party Sparked a Revolution. Da Capo Press, Cambridge MA 2011, ISBN 978-0-306-81962-9 .