State theory

A state theory or state philosophy deals with possible definitions, origins, forms , tasks and goals of the state as well as its institutional, social, ethical and legal conditions and limits. As a sub-area of political philosophy and the concretization of general political science, state theories often address issues that affect several individual sciences at the same time, including: philosophy , theology , political science , law , sociology and economics .

overview

A state theory can start from very different approaches:

- from historical or existing state systems that it describes, legitimizes or criticizes,

- from the ideal of a political order, such as a state utopia ,

- of economic or political-social power structures,

- from an idea of "morality" ( ethics ), derived from it and the like. a. the human rights and the separation of powers ,

- of a given order, be it “divine”, natural law or contractually agreed.

Depending on the epoch and the theoretical approach, actors in state theory can be:

- the sovereign ,

- the state as an abstract being itself,

- a nation ,

- the single person,

- the social class or

- the totality of the acting economic agents .

These subjects are at the same time objects of state theories, insofar as freedom and order in the construct of the state are (should) be balanced with one another in some way. B. as a power state, rule of law , " welfare state " or " classless society ". The subject of reflection is also the delimitation and assignment of various state tasks and powers - e.g. B. Legislative , executive and judicial branches - like the possible and real "balance of interests" of different groups that exist in the state together.

State theories can historically be assigned to different forms of society and derived from them. Depending on the epoch, they reacted to different needs and particular or general interests. One possibility to conceptually order their diversity is the question of the underlying “concept of man” (cf. Philosophical Anthropology ): If man is thought of as “good” in principle, a state theory based on the greatest possible democratic participation, social Is geared towards equality and diminution of power. If, on the other hand, people are seen as principally violent, striving for power, “evil” or potentially “dangerous” because of their fundamental indeterminacy, a state theory that legitimizes a freedom-limiting exercise of power by state authority is obvious.

The approaches also differ in their approach: A legal theory is e.g. B. more normatively and deductively , while a sociological theory analyzes the interest groups empirically and descriptively .

Greco-Roman theories of the state of antiquity

State theories from the time of ancient Greece do not refer to a state in the modern sense of a regional authority , but to the staff association of a polis (city-state). Even permanent residents (so-called Metöken ) had no civil rights in the respective polis and thus no right to vote .

Only in the kingdom of Alexander the Great , in the realms of his successors ( Diadochi ) and in the Roman and Byzantine Empire , a "state" developed in terms of a uniform written and ruled territory, be it as in the older empires of Egypt and Mesopotamia as a monarchy with ancient "God the King" ideology, be it as the representation of the citizenship through state organs such as the Roman Senate . But even this form of government did not yet correspond to the modern state because it basically excluded certain parts of the population from any political participation.

But even the Greek historian Herodotus ("father of historiography") noted in his constitutional debate that the whole state rests on the mass of the people (Herodotus, 3,80-84).

In his work Politeia, Plato built the ideal state analogous to the human soul . The three states correspond to one of the three parts of the soul:

- The philosophers (rulers) correspond to reason and thus form the teaching level ,

- the guardians (defense outside and inside) the courage; the armed forces ,

- the third level, the nutritional level (farmers and artisans) reflects the instincts .

A person is happy when his three parts of the soul are in harmony, in equilibrium: A state is also just when the three classes live in harmony. Plato described the moderate aristocracy and the constitutional monarchy as the best constitutions, and the nomocracy (rule of laws) as the second best . In Plato there is also the conception of a constitutional cycle , a temporal succession of different forms of government.

In his work Politics, his student Aristotle distinguished six forms of government :

- Monarchy (sole rule),

- Aristocracy (rule of the best),

- Politie (rule of reasonable members of society).

These three forms have the common good in mind and are therefore good. Their "degenerate" counterparts are

- Tyranny ,

- Oligarchy and

- Democracy ; to distinguish it from today's concept of democracy, it is often also called ochlocracy .

Aristotle also believed in a cycle of constitutions: a good form of government tends to "degenerate", the next good form then emerges from this "degenerate form", etc. He understood democracy as the rule of the unorganized mass of the poor who did not benefit the general public , but could only strive for their own good. However, he did not strictly reject a moderate form of popular rule, as his teacher Plato did, for example, but pleaded for a mixed constitution between democracy and oligarchy, which he also calls politics .

Even Cicero sought in his work De re publica optimal constitution and transferred it insights of Aristotle and the historian Polybius on the Roman Republic . Cicero interpreted the Roman system as an adequate realization of the mixed constitution with the consuls as the monarchical, the senate as the aristocratic and the popular assembly as the democratic element.

In the Roman Empire, however, the state was based on the virtually unlimited power of the monarch ( principate ), at least as long as his army supported it. This was already apparent in the Hellenistic monarchies, which partly drew their legitimation from ancient oriental sources.

Theological state theories

Christianity

Since the persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire , Christianity gained increasing influence on European state theories. Since the Constantinian turning point (325) and after it had become the only state religion (380-390), it strengthened the sole rule of the Roman emperor by blessing it as inalienable for salvation in the hereafter.

This salvation-historical dimension of the empire had an effect in the Middle Ages : the church, which was organized in a centralized and monarchical way, determined the worldview and religious policy of the Holy Roman Empire in the west and of the Byzantine Empire in the east (see Caesaropapism ).

The scholastic formulated on the basis of the designs Augustine ( De Civitate Dei to 420) and Aquinas ( Summa , 1265), a differentiated oriented on interaction of faith and reason state theory in which the natural law is the reference point.

The two kingdoms doctrine of Martin Luther for the first time established the strict separation between religion and political power. The Reformation , however, favored the formation of regional church regiments, later of absolutism and nation states , some with denominational national churches .

It was not until the French Revolution that the idea of the separation of church and state prevailed, thereby initiating an understanding of the state throughout Europe that was oriented towards internal tasks, the rule of law and more towards democratic state control than maintaining power. Counter-reactions such as the Holy Alliance , the Prussian-conservative Christian monarchy or the cultural war of political Catholicism failed in the long term.

Based on the experiences with totalitarianism , today's churches in Europe affirm and support the ideologically neutral constitutional state, which in turn guarantees and protects the freedom of belief and the right to resist .

Islam

In Islam , the Koran and the political philosophy of Muhammad form the basis of all politics. These demand a form of society based on Koranic principles, whereby religion and science as well as religion (see also state religion ) and politics are thought to be inseparable. This leads to a strongly religious conception of the state. Some predominantly Islamic countries anchor the Sharia in their constitution: This presupposes God's will, revealed in the Koran and in the Sunna , for all areas of life, which the scholars interpret in consensus and update through jurisprudence ( ijma ). This leads to theocratic forms of government directed by religious authorities.

According to more recent theological positions in Islam, however, the Koran does not exclude the possibility of separating state and religion. Reference is made to statements according to which the nations should select “the best among them for their leadership”. This statement includes popular sovereignty . Nevertheless, the government of an Islamic state, regardless of which form of government it can be assigned to, should be guided by the principles of the Koran. According to liberal Muslims, this includes freedom of belief ( la ikrah fi'd-din : “There should be no compulsion in belief”), freedom of expression and inalienable human rights.

The theory of an Islamic state is a concept that has played a major role in Islamic political thought since the middle of the 20th century.

Modern state theories

Power state theories

In his work Il Principe ( The Prince ) Niccolò Machiavelli founded the idea of the “power state” and derived it from the rule of the “strong”. The rule of the "strong" asserts itself empirically like a natural law in history and is based essentially on the consent of the "weak":

“A prince only needs to win and maintain his rule, so his means will always be considered honorable and praised by everyone. For the mob is always captured by the appearance and success, and there is only mob in the world; very few hold out if they do not find enough support. "

From this, Machiavelli concluded that the ruler should maintain power as a necessary raison d'être for the existence of the state and elevated it to the maxim of political action in general. In the end, he only established state power out of himself.

In his work Les six livres de la Republique ( Six books on the state ), Jean Bodin introduced the idea of sovereignty : the community is governed by supreme authority and reason, a constant and unconditional authority over all citizens, with the right to make laws to give or to cancel. The sovereign state is not responsible to any other earthly authority - it is, however, bound by divine law or natural law , which was defined in the scholastic discussions of the Middle Ages.

Contract theories

Contract theories understand the state from a fictitious legal agreement . The starting point is the description of a natural state in which there is still no state. After ancient Greek forerunners like Sophism , Johannes Althusius , Hugo Grotius and Thomas Hobbes in particular developed such state theories. Elements of the power state theories were also incorporated.

Thomas Hobbes derived the social contract in his book Leviathan from the natural state of war of all against all ( bellum omnium contra omnes ); The historical background was the denominational civil war in England and Scotland and the dispute between the king and parliament. In this natural state there is competition, mistrust and an addiction to fame. In this phase people are unable to perform because they fear each other. Human reason develops several doctrines ("natural laws") to overcome this natural state. Out of reason, a contract is voluntarily created by every person with every person. In it they undertake to limit their personal freedom and to transfer certain rights to a sovereign. They give the state an unrestricted monopoly of force so that it can protect the general public internally and externally from violent attacks. It is crucial that this sovereign has not signed a contract with the people. Its structure is not legally codified, but authoritarian and absolutist. The prince or an aristocracy or an assembly as a superordinate persona civilis embodies order. It is not his unlimited use of force that breaks the social contract, but rather the individual who rebels against him. The ruler himself is not bound by his laws, he speaks justice; Since the contract is based on submission, it does not contain any elements that limit power. It can only be terminated if the ruler can no longer guarantee the security of the people. The presumed consent of the individuals here legitimizes the absolute rule of a sovereign , as was common in Hobbes' time in France ( L´état c'est moi ).

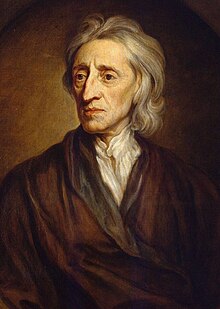

John Locke's contract theory, on the other hand, was enlightened and liberal . The state of nature he described was characterized by freedom and equality . Nevertheless, the irregularity also leads to instability. The low security of life, freedom and property in the natural state was the reason for the agreement on a monopoly of force. Unlike Hobbes, however, this state power is divided into the executive and legislative branches in order to counteract the abuse of power. Locke's theory of the division of powers still lacked an independent judiciary; In this context, however, he coined the term checks and balances , which was taken up by the authors of the Federalist Papers . In Esprit des lois, Montesquieu then developed a developed doctrine of the separation of powers, in which the judiciary plays the decisive role.

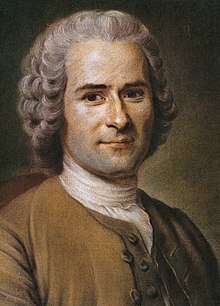

Jean-Jacques Rousseau , on the other hand, advocated a radical democratic theory of the state that does not justify what exists, but wants to be in accordance with human nature and based on the identity of the rulers and the ruled. Like Locke, he saw the state of nature characterized by freedom and equality. According to Rousseau, their loss did not take place voluntarily, but through external influences, and culminated in the intermediate stage of socialization . The future social contract is now intended to restore irretrievable natural freedom on a higher level than social freedom. So it should not limit and give up basic human characteristics, but rather preserve and defend them as "basic rights". That is why Rousseau asked ( Contrat social II, 15):

"How do you find a form of society that defends and protects every member and in which each individual, although he unites himself with everyone, still obeys only himself and remains as free as before?"

This formulates the basic problem of democracy : the autonomy of the individual is not viewed as a contradiction and a potential threat to state sovereignty, but as its irretrievable precondition. Their protection is therefore the main state task. But how can free individuals establish a general order?

Rousseau saw the solution in popular sovereignty : only as a sovereignly decisive entity can every citizen ( citoyen ) preserve his freedom, that is, only through politically equal participation in all decisions. The common will cannot be delegated, but must be borne by as many as possible, generally all citizens, in order to be universally valid. The lawful state can only be based on the collective decision of all citizens.

Since this is almost never achievable in real terms, Rousseau introduced the majority principle as an approximation to the state ideal. After the conclusion of the contract, sovereignty remains with the people. It cannot be transferred to representatives or institutions . Citizens should not cede their will to the general public, but should bring it in as far as possible.

In the opinion of many critics, Rousseau was unable to answer convincingly how a social order can be achieved with the freedom of the individual . Because it requires - as Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (see below) in particular postulated - an "objectified" value system that should not depend on the changing voting behavior of the majorities. Such a voluntary self-limitation would, however, contain a contradiction to popular sovereignty, namely its partial limitation. Without this, contract theory could not adequately justify the necessary transition from freedom of the individual to a permanent social contract for both idealistic and Marxist state theorists.

After a temporary departure from contract theory in the 19th century, it experienced a renaissance in the 20th century with John Rawls ' work A Theory of Justice . Rawls introduced the fictional veil of ignorance in his social contract theory of egalitarian liberalism . With the conclusion of the contract, the individuals determine what justice should look like in the future society. The veil of ignorance now prevents individuals from knowing their future social position and their natural talents or abilities when the contract is concluded . This objectivity excludes utilitarian action by the individual individuals when the contract is concluded and thus leads to a just agreement.

Idealistic state theories

In idealistic state theories, as in contract theories, the state was viewed as a consensus of autonomous individuals. Their “morality” was assumed, which enables a distinction between “good” and “bad”. The enlightened ethics therefore appealed not only to formal freedom of choice, but also to the substantive insight into the necessity of sensible behavior that strives for the common good.

Immanuel Kant combined liberal and democratic ideas. The state is justified if each individual can feel himself to be a co-author of law and the state through his or her theoretical possibility of consent ( legal theory §47):

“The act by which the people constitute themselves into a state, but actually only the idea of the same, according to which the legitimacy of the same can be thought alone, is the original contract according to which everyone (omnes et singuli) in the people gives up their external freedom to see them as members of a common being, d. H. of the people as a state (universi) to resume immediately. "

The reflection of the “good will” shows the individual the state as a product of his own will and aims at agreement of the whole of the people. The state should organize the coexistence of people as well as possible so that everyone is able to carry out the activity he can best: Its purpose is to balance freedom and order, individual interests and general interests, which include the development of individual abilities.

Why the (fictitious) approval of the state, once it has been made, should not be revisable remains open with Kant. Here z. B. Johann Gottlieb Fichte that the individual by virtue of his freedom of choice can terminate the state treaty at any time and leave the community, so that mutual rights and obligations are no longer applicable. This means that a free choice of different forms of government is just as conceivable as the collapse of the consensus on a common order, ie “ anarchy ” and relapse into the “ war of all against all”. This touches on the problem that the form of social organization and the institutions should give support and continuity to the rights and duties of citizens.

Hegel tied in with Plato and Aristotle in that he saw the moral existence of man as realized only in the state. He praised the idealism of Rousseau and Kant, who had made the freedom of the individual and thus the spirit the basis of all law and organization of coexistence, but showed in his legal philosophy as the weak point of contract theory that it had derived the state only from the sum of individual interests in which every citizen is "an end for himself". For him, the state was only born out of necessity and abstract understanding, but thus abandoned to arbitrariness and tends to be destroyed. On the other hand, the state must be understood as identical with “absolute authority and majesty”: as the embodiment of an objective will which is “that which is in itself reasonable in its conception, whether it is recognized by the individual and willed at his will or not [...] . "

In doing so, Hegel did not want to abolish individual freedom again in an absolutism: for him, the state is not a natural given, but an ideal of freedom that tends to be realized in the world. He was looking for a synthesis of an ordered polis, which encompasses and determines the individual life (antiquity) and personal development, which is based on the infinite value of the individual (Christianity). Hegel found this ideal realized in the (Prussian) state:

“The state is the reality of concrete freedom; Concrete freedom, however, consists in the fact that personal details and their particular interests have both their complete development and the recognition of their rights for themselves […], as they pass through themselves into the interests of the general […] […], namely as their own substantial spirit and are active for the same as their end purpose, so that neither the general is valid and accomplished without the special interest, knowledge and will, nor that the individuals live only for the latter as private persons, and not at the same time in and want for the general and have conscious effectiveness for this purpose. "

The welfare state

We speak of a welfare state when social security is not aimed solely at needy groups, but at the majority of the population. Most states developed into welfare states between the 1920s and 1960s.

The development of the welfare state is based on the social upheavals in the age of industrialization . With the establishment of the industrial mode of production, the population group of workers was exposed to new risks such as invalidity (due to an accident at work) and unemployment. Other risks such as illness and old age were not new, but the traditional support systems such as the extended family lost their importance due to the need for professional mobility or, as in the case of the guild system, were abolished in the 19th century. The most important political prerequisite is the emergence of trade unions and socialist parties, which the rulers saw as a threat. One wanted to meet certain interests of the workers on the one hand and on the other hand to pacify social conflicts with the rising workforce. A cultural prerequisite was the change in social patterns of interpretation. The Enlightenment gave rise to the idea that living conditions were neither god-given nor natural law. In the 19th century, the idea gradually gained acceptance that the state was the appropriate instrument for coping with complex collective tasks.

The basic structure of the German welfare state was created towards the end of the 19th century with the introduction of the most important social insurance schemes ( pension insurance , health insurance and accident insurance ) as part of the Bismarckian social reforms. In the beginning, however, only factory workers were covered by social insurance. Other people in need of protection such as the rural population, white-collar workers and industrial workers were only gradually recorded. It has only been possible to speak of a fully developed welfare state since the late 1960s.

Liberals criticize this state model : The institutionalization and bureaucratization of aid inevitably lead to a lack of freedom, incapacitate people and give the state administration too much power. It solidifies reciprocal claims and fulfillment attitudes among the recipients of aid and the legislature, thereby weakening their responsibility for society as a whole and thus undermining democracy. Often direct lines of development were drawn from the “welfare dictatorship” to totalitarian fascism or Stalinism . Even before 1900, some critics contrasted this with the minimal state , which is only responsible for internal and external security and should not influence the free market through economic or social policy ( laissez-faire ). Your opponents called this conception the night watchman state .

Socialist state theories

Socialism strives for the socialization or nationalization of the means of production in order to overcome the capitalist economic system. What role the state can and should play in this is answered very differently in the socialist directions.

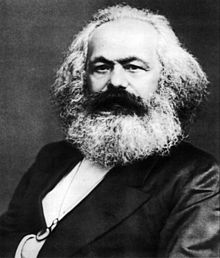

Karl Marx viewed the actually existing state as an expression of class rule. Only after a successful international revolution of the working class is a state ( dictatorship of the proletariat ) conceivable that serves the common good. In communism a classless society would then be reached, which would make every state superfluous and let it wither away (see Marxism ).

On the one hand, Lenin drafted a theory of the revolution “from the weakest links” of capitalism, combined with the concept of a cadre party. On the other hand, he emphasized the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat and the supremacy of the party. The revolution takes place in the form of the assumption of state power by the proletarian elite supported by the workers' councils: the building of socialism will then be made possible through central administration and planning of all social needs. Lenin's model was the Prussian official state (see Leninism ).

Under Josef Stalin the theories of Marx and Lenin were welded together into a " Marxism-Leninism ". This served as a state ideology to legitimize a centralized one-party dictatorship with bureaucratic-feudal features and was intended to establish an authoritarian leadership role for the Soviet Union in the communist movement. The core of this state theory was the equation of the proletariat (people) with the unity party and the state, so that the separation of powers was abolished by a central control of all areas of society from top to bottom (see Stalinism ).

Leon Trotsky , organizer of the October Revolution , founder and leader of the Red Army in the Russian Civil War , had countered Stalin's dictatorship with his theory of permanent revolution . He tried to overcome the national limitation and the paralysis of communism with the continuation of the world revolution in developed industrialized countries as well as in countries of the "periphery" dependent on the world market. The ideas of workers' self-management and internationalism were given a higher priority again (see Trotskyism ).

Like Lenin, Mao Zedong had drafted and successfully practiced a theory of revolution in which the “rural proletariat” - the peasants - played a central role. In addition to Marx and Engels, Maoism also explicitly referred to Lenin and Stalin. The bureaucratic-feudalist one-party dictatorship in the People's Republic of China was even more rigid than in the former Soviet Union (see Maoism ), despite internal wing struggles, economic liberalization and rapprochement with capitalism .

In contrast, the multi-ethnic state of Yugoslavia under Josip Broz Tito was regarded as a form of socialism independent of the Soviet Union, which tried to combine state control of the economy with privatized agriculture and non-aligned foreign policy (see Titoism ).

The leading representatives of the Spartakusbund , Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg , preserved the internationalism committed to Karl Marx since 1914: A social revolution can only be successful on the basis of effective practical solidarity of all workers' parties. As a result of the World War they expected and advocated a communist world revolution instead of a parliamentary realization of social justice, but rejected Lenin's concept of a cadre party for the conquest of state power. Rosa Luxemburg had welcomed the October Revolution in her posthumously published work “The Russian Revolution”, but sharply criticized Lenin's tendency towards a one-party dictatorship excluding workers' self-government and diversity of opinion. She did not draft a new socialist theory of the state, but emphasized the spontaneity of the proletariat as an impetus for constant rethinking by the left parties. The socialization of the means of production should be represented politically in the form of a council republic (grassroots democracy) in order to protect socialism from centralist rigidification and reformist aberrations.

In contrast to Stalinism, Western European Eurocommunism was looking for a parliamentary path to socialism and aimed at a decentralized mixed economy without central planning. B. Antonio Gramsci , Louis Althusser and Nicos Poulantzas .

Reformist state theory

Various currents have been united in the SPD since it was founded: a more Marxist one, represented by August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht, and a union-pragmatic one, represented by Ferdinand Lassalle . The reformism theoretically founded by Eduard Bernstein became their common concept around 1900, while the program continued to aim at a revolutionary overcoming of class rule. The social problems should be gradually alleviated and finally resolved through democratic reforms within the framework of the existing class society. This included the partial nationalization of the means of production within the framework of a liberal democracy .

In 1959, the Godesberg program of the SPD officially renounced many of the old Marxist demands in order to turn the class party into a parliamentarily successful people 's party . This made a commitment to the social market economy and accepted means of production as private property. Further demands in the program are the rule of law and the free development of people through and with social security in the welfare state.

Anarchist criticism of the state

Anarchism's criticism of all state models, which should be abolished, reflects a negative state theory. All involuntary authority in general and state rule in particular should be abolished. The focus is on freedom, autonomy and self-administration of the individual, coercion is rejected, but not self-defense in the event of attacks. There are different nuances:

- Mutualist anarchism ( Pierre-Joseph Proudhon )

-

Collectivist anarchism ( Michail Alexandrowitsch Bakunin )

A form of anarchism that u. a. propagated the abolition of traditional property claims. -

Communist anarchism ( Peter Alexejewitsch Kropotkin )

The goal is a stateless society based on mutual aid .

Decision-making takes place at the lowest level, without any hierarchies or constraints. That means that the municipalities are self-governing . The decisions are therefore made in a voluntary and equal agreement of all citizens of a single smaller area, which also includes the communal businesses. The decentralized municipalities in turn federate with other municipalities in order to coordinate higher-level tasks and to exchange ideas with one another.

Libertarian criticism of the state

From the point of view of libertarianism , the state is an illegitimate coercive apparatus that restricts freedom. A free order of the community based on contracts between individuals is the only legitimate one.

Like anarcho-capitalism , libertarianism is based more strongly than (other) anarchist criticism of the state on economic considerations. For example, he rejects market failure as a legitimation for state action and sees state regulations as unjustified favoring individual economic actors.

The distrust of government regulations is often justified historically. So both the emergence of the state as a whole and the emergence of the welfare state were power and interest-driven. Libertarians point out that all social insurances arose from voluntary self-help organizations.

Current State Theory Debate

The point of reference for the current state theoretical debate are in particular the state teachings of the Weimar Republic, namely by Hans Kelsen , Carl Schmitt , Hermann Heller and Rudolf Smend . All of them formed influential schools or schools of thought and continue to have an impact on today's state debate. The " Allgemeine Staatslehre " (1900) by Georg Jellinek had a formative influence on the Weimar State Discussion, which went hand in hand with the methodological dispute over Weimar constitutional law . In it he developed a three-element doctrine , according to which the three characteristics "national territory", "state people" and "state authority" are required to recognize a state as a subject of international law (see international law ). In addition, Jellinek split the state doctrine into a general social doctrine and a general state doctrine.

Legal and “sociological” concept of the state in the Weimar Republic

For the neo-Kantian Hans Kelsen and his “ pure legal theory ”, the state was something purely legal, that is, something that was normatively valid. It is not some kind of reality or an imaginary next to or outside of the legal system, but nothing but this legal system itself. The state is therefore neither the author nor the source of the legal system. For Kelsen, such ideas were “personifications” and “hypostatizations”. For him, the state was rather a system of attributions based on a final attribution point and a final basic norm . From this purely legal point of view, the state is therefore identical to its constitution; it remains free from anything sociological.

Carl Schmitt, on the other hand, was interested in what he called the "sociological" question of how the state constitutes itself as the "political unit of a people". For him, the achievement of a state as a "decisive political unit" was to bring about complete pacification within its territory and thereby create a situation in which legal norms can apply. The state is basically subordinate to the “political”: “The concept of the state presupposes the concept of the political”. The concept of the state can therefore no longer form the fundamental category, because it no longer achieves what it is supposed to do, namely to denote political unity. In this place comes the political, the concept of which can no longer be derived from the concept of the state.

This opens up new perspectives. During the time of National Socialism , for Schmitt, new types of “large areas” opened up beyond the state, which demanded the “overcoming of the old, central concept of the state”. Also avoid the political on non-state actors, e.g. B. the partisans as irregular, non-state combatants, whose absolute declaration of enemy is no longer compatible with the attempt of classical international law to integrate them into the sphere of public law . In the end, however, Schmitt's concept of the state was still related to a static state will coming from above and outside, which, however, referred to an element from below through the reference to the political unity of the people and thus potentially to the dynamics of modern society . When democracy abolishes the opposition between state and society , the state becomes the “self-organization” of society. The equation state = politically is no longer correct, because all previously only state affairs are now social and all previously solely social matters are state. Thus, for Schmitt, the state inevitably became a “ total state ” that potentially encompasses every subject area - including and especially the sphere of the economy . In doing so, Schmitt is focusing on the dynamic development of modern societies that is only dominated to a limited extent by state and legal authorities: “The era of statehood is coming to an end. [...] The state as the model of political unity, the state as the bearer [...] of the monopoly of political decision-making [...] is dethroned ”. The “sociological” question of the creation of a “political unity” led Schmitt to the field of the “political” - that is, the association and dissociation of people - and ultimately beyond the state.

Hermann Heller also referred to sociological moments in his “Staatslehre” (1934) when he emphasized the “reality of the state”. For him, the state was a "unit active in social reality" that does not exist separately from the respective reality, but always has to form and justify itself from the changing reality. The state as a political unit cannot be identified with “society”. The state is necessary "organized" unit, which receives its shape and capacity to act through appropriate institutions . Since the law of organization is the fundamental law of education of the state, the unity of the state is always only the result of conscious unification, instead of being understood as an organization. In order to be able to fulfill its functions, the state needs an organizational display of power. The will of the state is mediated by state organs as “ rule ”, not by social forces acting at will. The forces that permanently shape it make up the “reality of the state”. These forces, parties , groups and associations , as concrete structures, are the prerequisite for the democratic process. However, these structures are in turn dependent on preconditions, namely on a “political community of values” and “social homogeneity ”. State unification would not be possible without a minimum of social homogeneity. This is the basis of what Heller first called the “ social constitutional state ”.

The fourth state theory design from the group of major Weimar constitutional law is the integration of teaching Rudolf Smend . Smend was assigned to the "humanities school" of state theory, which turned against legal positivism and formalism with a sociological concept of the state. Smend understood the state as a “spiritual reality”, whose “life process” was based on a “dynamic-dialectical character”. This dynamic understanding of the state is also reflected in the fact that state organs and powers are not understood as substances of a dormant nature, but as moving forces. The state is only because and insofar as it is permanently integrated. He lives only in this process of constant renewal, constant re-experiencing. In a sense, he lives from a plebiscite that repeats itself every day.

The constitution, as the legal standardization of individual sides of this process, sets the task of forming unity. In 1928, in his main work “Constitution and Constitutional Law”, Smend developed a doctrine of the possibilities of integrating citizens into the state. The essential achievement of the state is to establish and maintain that integration. Smend distinguished three main types of integration. He was the first to name the “personal integration” of a legitimate monarch who symbolized the “historical existence of state community values”. He referred to the second type as “functional integration”, in which certain values established rule , namely irrational ones that give it legitimacy and rational ones that justify it primarily as administration .

As a third type, Smend thought he could identify a sphere of “factual integration”, which is based primarily on “ symbols ” and “space” as integration factors. The fullness of the state salary can no longer be grasped by the individual, which is why it must be represented by symbols and processes aimed at representing the community . In this way, the integrative effect of the state can be experienced intensively, not extensively. History is one of the most powerful factors in the state's ability to integrate, as it illustrates the fluid and not the static. Even more important is only the state territory through which the state experiences its most essential concretization , so that it comes first among the factual integration factors. According to Smend, time and space are two of the most important factors in factual integration.

Sociological theory / power theory

The state is seen as a logical consequence of exercising power or rule . According to the sociological state idea formulated by Oppenheimer in 1909 , the state is originally “a social institution that was imposed by a victorious group of people on a defeated group of people with the sole purpose of regulating the rule of the first over the last and protecting against internal uprisings and external attacks . ”After Machiavelli had already examined the forms, acquisition and maintenance of rule in the 16th century in his work Il Principe , the focus today is on Max Weber's sociology of rule . Weber understands the exercise of power and domination in terms of a subjective sense of action. His main interest was the relationship between the rulers and the ruled, the competition for political office and the actions of political elites . For Weber (Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, 1922) the state defines itself as that human community which successfully claims the monopoly of legitimate physical violence within a certain area. Weber distinguishes between three ideal types of legitimate rule according to the type of belief in legitimacy:

- rational or legal rule by virtue of a set order (e.g. bureaucracy ),

- traditional rule by virtue of belief in the sanctity of the orders and powers that have always existed (e.g. patriarchy , feudalism ) and

- Charismatic rule based on affective devotion to the person of the Lord and their gracious gifts ( charisma ) (e.g. prophets ), which is always objectified in a rational or traditional rule.

In his work, Legitimation Through Procedure, Niklas Luhmann takes up the idea of the legitimacy- indicating legality of the type of legal rule. In Macht (1975) he uses the term “state” in quotation marks. And in Die Politik der Gesellschaft (2000), Luhmann defines the term as a “semantic institution”: the state is not a political system, but the organization of a political system for self-description of this political system.

Jürgen Habermas commented on legal rule that if one presupposes a reference to truth for an effective belief in legitimacy, the process of establishing the order cannot generate legitimation as such, but that the process of establishing the order itself is also subject to compulsion to legitimize. Therefore, additional arguments for the legitimizing power of the regulatory procedure would have to be given, e.g. B. the rules and competencies in this regard laid down in a constitution .

Hermann Luebbe spent here against a turn that between argumentative standard justification and decisionist Norm enforcement is distinct (which he rather standard -setting may have meant). In the parliamentary debate, legitimation comes through voting.

In contrast to Weber, Michel Foucault understands the exercise of power and domination as a subjectless strategy. In his power theory, he starts from a strategic-productive concept of power and relates power and knowledge to one another.

Relatively late, that is intensively only since the late 1980s and early 90s, who were also of feminist or gender studies ( gender studies ) state and democracy of the examined critically to power and domination, previously was a critical state theory virtually a blank feminism of Women's movement. The aim of a feminist conceptualization of statehood is to make the “gender of the state” visible and, as a result, to deconstruct the state-institutional structures and mechanisms that maintained the hierarchical bisexuality. The state is recognized as a condensation of the existing social contradictions: the structural masculinity of its institutions (“ Männerbund ”), its interests and its organizational rules, values, norms and structures are exposed and criticized by gender research that is critical of society and the state (Sauer 2003).

The liberal-feminist direction, on the other hand, relates positively to the state, which, as a neutral mediator, should represent the various interests. With a view to the Scandinavian welfare states, he only lacks mechanisms to promote women. The male family breadwinner model on which the state is based and the resulting double socialization of women is rarely questioned (Sauer 2003).

Democracy theory

The representative democracy that is valid in Germany today has, for example, Bruno Schmidt-Bleibtreu et al. a. defined in his commentary on the Basic Law :

“First of all, democracy consists in the fact that, in principle, the people themselves exercise the functions of the state, although, for practical reasons, never all members of the people and not even all adult members of this people can exercise power, but only the largest possible number of them, i.e. the majority .

Secondly, this exercise of rule by the majority does not usually take place directly today, i.e. not through direct decisions on government and legislative acts by means of a referendum, but it is carried out regularly [...] through the election of a representative body, the legislature, which in turn is regularly through election the government, the executive, appointed.

Finally, part of the concept of democracy is that this election of the state organs takes place on a temporary basis, if not on demand, and that the elections are free and based on the equality of the right to vote for all adult citizens. "

These characteristics take up the human rights, rule of law and democracy traditions established by the philosophers of the Enlightenment - above all Locke , Montesquieu , Rousseau and Kant - and anchor them constitutionally:

- Popular sovereignty ,

- Majority principle ,

- Parliamentarism ,

- Separation of powers ,

- Rule of law, especially with regard to human dignity , freedom of expression and from there secret, equal and free right to vote ,

- ideological neutrality,

- Opinion and party pluralism .

The Basic Law wants to avoid construction principles of the Weimar constitution , which the Parliamentary Council viewed as undesirable developments. In the Weimar Constitution, for example, fundamental rights were not fundamentally exempted , i.e. they were placed above state authority, but were understood - in the form of defensive rights against the state - as the granting of the state to the citizens. The fundamental rights could be changed by a qualified majority "regardless of the scope", as the leading constitutional commentary put it. At the same time, the Weimar Constitution renounced an unchangeable national goal, which is why critics complained that it was "neutral" to any political goal. In the Basic Law, on the other hand, “inviolable human dignity” is understood as a positively qualified basis and content of democracy, which is intended to carry and pervade all other fundamental rights and individual laws. That is why the basic rights themselves are indispensable and are not subject to a majority decision. The " defensive democracy " understood in this way should not allow arbitrary political goals, but rather set political parties and state organs absolute limits.

This conception of democracy has established itself in most of the western-oriented states of today - especially in Europe and North America. It claims a general basis of values, human rights , as the basis of all rule of law. In the UN Charter , these are also proclaimed as the universal basis of international relations. According to the Western understanding, rule of law democracy therefore tends to be a generally applicable state model. However, it is subject to constant reassessment and redefinition even within democratically constituted societies as well as between different peoples, cultures and forms of government.

See also

literature

Classical works

-

Plato : Politeia

- The State. ISBN 3-15-008205-6 .

-

Aristotle : politics .

- The political things. ISBN 3-15-008522-5 .

-

Cicero : De re publica . 54 to 51 BC Chr.

- From the community. ISBN 3-15-009909-9 .

-

Augustine : De civitate Dei . Around 420

- From the state of God. ISBN 3-423-30123-6 .

-

Thomas Aquinas : De regimine principum .

- About the rule of the princes. ISBN 3-15-009326-0 .

- ders .: Summa theologica . 1265 or 1266 to 1273.

- Sum of theology

-

Dante Alighieri : De Monarchia . Around 1316.

- About the monarchy

-

Marsilius of Padua : Defensor Pacis . 1324.

- Defender of Peace

-

Nikolaus von Kues : De concordantia catholica . 1433/34

- About general unity

-

Niccolò Machiavelli : Il Principe . 1513

- The Prince. ISBN 3-15-001219-8 .

- Martin Luther : From secular authority. 1520.

-

Jean Bodin : Les six livres de la Republique. 1576.

- Six books on the state. ISBN 3-15-009812-2 .

-

Thomas Hobbes : Leviathan . 1651.

- Leviathan. ISBN 3-15-008348-6 .

-

John Locke : Two Treatises of Government.

- Two treatises on government. ISBN 3-15-009691-X .

-

Montesquieu : De l'esprit des lois. 1748.

- From the spirit of the law. ISBN 3-15-008953-0 .

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau : You Contrat social. 1762.

- Alexis de Tocqueville : De la démocratique en amérique.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau: You contract social ou principes droit politique.

-

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon : Système des contradictions économiques ou Philosophy de la misère. 1846.

- System of economic contradictions or philosophy of misery. Kramer, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-87956-281-4 .

- Marx / Engels: Communist Manifesto . 1848, ISBN 3-88619-322-5 .

- Karl Marx : On the Jewish question . 1843; MEW Volume 1.

- Friedrich Engels : The origin of the family, private property and the state . 1884

-

Mikhail Bakunin : Государственность и анархия (Gosudarstvennost i anarchija). 1873.

- Statehood and anarchy. ISBN 3-87956-233-4 .

-

Pyotr Kropotkin : La conquête du pain . 1892.

- The conquest of the bread. ISBN 3-922209-08-4 .

- ders .: Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution . 1902.

- Helping each other. ISBN 3-900434-27-1 .

- Georg Jellinek : General state theory. 1900.

- Franz Oppenheimer : The state .

- Lenin : State and Revolution . 1917

- Max Weber : Economy and Society . 1922, ISBN 3-16-147749-9 ( online text )

- Hans Kelsen : General state theory. 1925.

- Carl Schmitt : constitutional theory. 1928.

- Eugen Paschukanis : General legal theory and Marxism. 1929.

- Karl Barth : Christian community and civil community . 1946.

-

John Rawls : A Theory of Justice . 1971.

- A theory of justice. ISBN 3-518-06737-0 .

- Nicos Poulantzas : L'état, le pouvoir, le socialisme. 1977.

- Reinhold Zippelius : General state theory. Political science. 17th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-71296-8 .

Further literature

- Andreas Anter / Wilhelm Bleek : Concepts of the state: The theories of German political science. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2013, ISBN 978-3-593-39895-2 .

- Lars Bretthauer, Alexander Gallas , John Kannankulam , Ingo Stützle (eds.): Poulantzas read. On the topicality of Marxist state theory. VSA, Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-89965-177-4 ( introduction )

- Alex Talbot Coram: State, Anarchy, Collective Decisions - Some Applications of Game Theory to Political Economy. 2001 (state vs. anarchy from a game theory perspective).

- Alex Demirović : Nicos Poulantzas: Topicality and Problems of Materialistic State Theory. Westphalian steam boat, Münster 2007, ISBN 978-3-89691-622-8 (review by B. Opratko)

- Joachim Hirsch : Materialistic State Theory. Transformation processes of the capitalist state system. VSA-Verlag, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-89965-144-8 .

- Joachim Hirsch: The national competitive state. State, democracy and politics in global capitalism. Berlin / Rotterdam 1995, ISBN 3-89408-049-3 .

- Walter Kreck : Basic questions of Christian ethics. Kaiser, Munich 1975, ISBN 3-459-01019-3 .

- Martin Kriele : Introduction to the theory of the state. The historical bases of legitimacy of the democratic constitutional state. 6th, revised and expanded edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-17-018163-7 .

- Birgit Sauer : State, Democracy and Gender - Current Debates. In: gender… politics… online. August 2003 ( PDF; 420 KB )

- Klaus Thomalla: "The rule of law, not of people". On the history of ideas of a topos of state philosophy. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2019, ISBN 978-3-16-156105-4 .

- Rüdiger Voigt , Ulrich Weiß (Ed.): Handbook of state thinkers. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-515-09511-2 .

- Rüdiger Voigt (Ed.): State thinking. On the state of state theory today . Nomos, Baden-Baden 2016, ISBN 978-3-8487-0958-8 .

- Jens Wissel & Stefanie Wöhl (eds.): State theory facing new challenges. Analysis and criticism. Westphalian steam boat, Münster 2008, ISBN 978-3-89691-747-8 (review by I. Küpeli)

- State theory. Political superstructure, ideology, authoritarian statism. VSA-Verlag, Hamburg 1978, ISBN 3-87975-161-7 .

- Reinhold Zippelius : History of the state ideas. 10th edition. Beck, Munich, 2003, ISBN 3-406-49494-3 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Carsten G. Ullrich, Sociology of the Welfare State, Campus Verlag, Frankfurt, 2005, ISBN 3-593-37893-0 , p. 17.

- ↑ a b Carsten G. Ullrich, Sociology of the Welfare State, Campus Verlag, Frankfurt, 2005, ISBN 3-593-37893-0 , p. 23.

- ^ Carsten G. Ullrich: Sociology of the welfare state. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt 2005, ISBN 3-593-37893-0 , p. 25.

- ^ Stefan Blankertz: Critical introduction to the economy of the welfare state. 2005, p. 130 ( PDF; 329 KB )