October Revolution

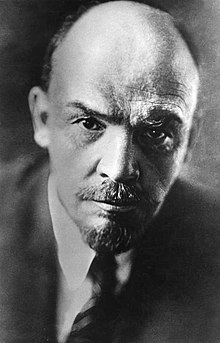

The October Revolution ( Russian Октябрьская революция в России , Oktabrskaja Revoljuzija w Rossii) of October 25th July. / 7th November 1917 greg. was the violent seizure of power by the communist Bolsheviks under the leadership of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin in Russia . It eliminated the dual rule of the socialist - liberal Provisional Government under Alexander Kerensky and the Petrograd Soviet, which had emerged from the February Revolution . It led to a civil war lasting several years and after its end in 1922 to the establishment of the Soviet Union , a dictatorship of the Russian Communist Party .

In socialist countries usually called Great October Socialist Revolution (Russian Великая Октябрьская социалистическая революция Velikaja Oktjabr'skaja socialističeskaja revolucija ) and glorified as a turning point in human history, the opponents of the Bolsheviks regarded the October events as a mere coup , the results show a solidified after a bloody civil war.

The term October Revolution was deliberately coined in order to upgrade the events compared to the previous February Revolution, which after all had resulted in the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and the end of the Russian monarchy . The designation of both events after the months of February and October is based on the Julian calendar still used in Russia at that time . According to the Gregorian calendar valid in the rest of Europe , which was 13 days ahead of Julian, but was only introduced in Russia in January 1918, both events occurred in the respective following months. Therefore, the anniversary of the October Revolution in the Soviet Union was always celebrated on November 7th.

causes

Dual power

The February Revolution had led to the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II (1868–1918) and tsarism , but hardly brought a solution to Russia's most important social and political problems. The most pressing question was whether or not the First World War , which had been ongoing since 1914 , should be continued on the side of the Entente powers . The demands of the modern, industrial war exceeded the strength of the largely agrarian country, so that the already grave social problems in Russia worsened. To make matters worse, the revolution had created a coexistence of two competing centers of power:

- The Provisional Government , which was initially led by the liberal Prince Georgi Lwow (1861–1925), who belonged to the Constitutional Democratic Party , the so-called Cadets; from July 1917 was headed by the socialist Alexander Kerensky . She advocated reforms based on the Western model, but also the continuation of the war. Kerensky's meanwhile strong position in power was based on the fact that he was the only member of the Provisional Government who was also a delegate of the Petrograd Soviet .

- This Petrograd Soviet , the capital's workers 'and soldiers' council , was spontaneously formed by insurgents at the beginning of the February Revolution and also claimed legislative power . He advocated a council system on the constitutional question . As an executive body, he created an Executive Committee, which was expanded in June 1917 with the addition of delegates from other parts of Russia to the 1st All-Russian Central Executive Committee . Here the agrarian Socialist Social Revolutionaries and the moderate Marxist Mensheviks dominated , the Executive Committee was a pillar of the Provisional Government. Both organs met in the Tauride Palace .

A Russian Constituent Assembly should decide on the final constitution . The Provisional Government was faced with repeated demands from the Entente partners, who were determined to prevent Russia from leaving the war. Therefore it refused to accept large parts of the Russian population to enter into negotiations with the German Empire and the other Central Powers on a separate peace . On February 16, Jul. / March 1, 1917 greg. The Menshevik-dominated Petrograd Soviet issued Order No. 1 , which limited the soldiers' duty of obedience to orders that did not contradict its own orders and decisions. The weapons of the individual units were handed over to the control of the workers' commissions that were to be formed, and officers were forbidden to use the terms of the soldiers. This contributed to the disintegration of the army. This accelerated even further because of the massive desertions : the Provisional Government had set up land committees all over the country to prepare land reform . Numerous peasant soldiers now thought that a redistribution of the land was imminent and hurried home from the troops to take possession of the desired properties. The Kerensky Offensive , with which the Provisional Government wanted to force a breakthrough against the advancing German troops in July 1917 , turned out to be a "disaster" under these circumstances and contributed to the final disintegration of the Russian army .

In reality, the Provisional Government did not intend to initiate a large-scale redistribution of the land , as is the case with the bulk of the Russian peasantry (about 80% of the total population) and the Social Revolutionary Party, which they represented and which also participated in the Provisional Government , have long been demanding. Liberals and socialists disagreed over whether expropriations should be allowed and whether compensation should be paid if necessary . As a compromise, they agreed to reserve answers to these questions to the Constituent Assembly. Because the hoped-for agrarian reform did not materialize, the farmers in many villages took the land and drove the large landowners out by force .

Economically, Russia was approaching collapse. The inflation caused by the war resulted in a tripling of the cost of living compared to 1913. Wage increases and additional income from overtime only partially offset the price increases for the workers. The eight-hour day and the first maternity protection measures that the Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet had agreed with local employers in April 1917 did not make the workers more peaceful. The result was a wave of strikes in May 1917 , which increased until October 1917, when over a million Russian workers were on strike. This further worsened the economic situation, which is why companies began to send their workforce on vacation or lay off due to losses and supply problems. As a result, factory occupations were the result, after which the workers' works committees often switched to producing things on their own in the disused factories that they could sell or barter on a daily basis. Under the conditions of these unplanned socializations, the Russian economy was moving towards a return to barter .

The cohesion of the Russian Empire, in which the Russians were only a minority with 44% of the total population, was also in danger under the Provisional Government, which believed that it had done enough by abolishing the discriminatory laws that had been in force until then. Nationalists in Finland, Poland and the Baltic states were betting on secession from Russia and the establishment of their own national states , while other sub-peoples still left with demands for autonomy . When the Provisional Government, in its insistence on a unified Russian state, refused any concession, for example towards the Central Na Rada of Ukraine , the cadets in the Provisional Government also provoked it to a clearer separatism .

Lenin

The leader of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party , Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (1870–1924), pleaded in his exile in Switzerland for “revolutionary defeatism ”. In order to “turn the world war into a civil war”, he aimed for a military defeat for Russia as the result of which he foresaw a revolution in Russia and around the world. Thus there was a temporary convergence of interests between him and the German imperial government , which hoped that the intervention of Lenin and other revolutionaries in political events would further destabilize Russia in order to derive military benefit on the eastern front . The imperial government therefore made it possible for him to travel from Zurich via Germany, Sweden and Finland to Petrograd ( Lenin's journey in a sealed car ). The exchange of Russian exiles for Germans interned in Russia, originally initiated by the leading Menshevik Julius Martow (1873-1923), was delayed by the Provisional Government, as Foreign Minister Pavel Milyukov (1859-1943) in particular was against a return of the defeatist revolutionaries. Lenin and 31 other exiles, however, pressed for a return as soon as possible. Through the mediation of the Swiss communist Fritz Platten (1883–1942) and the German-Russian socialist Alexander Parvus (1867–1924), the German authorities supported him on this trip. The group drove in a sealed railway wagon to the German Baltic coast in order to travel on from there by ship.

After arriving in Petrograd on April 7th, Lenin published Jul. / April 20, 1917 greg. his April theses , in which he spoke out against any cooperation with the Provisional Government. Instead, he demanded “all power to the Soviets”, an immediate end to the war, expropriation of large estates, socialist control over industry and nationalization of the banks. This abrupt rejection of any form of cooperation with other socialist groups, with which the Bolsheviks had until then felt that a bourgeois revolution had to take place before a socialist one, caused disturbance everywhere, not least among the Bolsheviks themselves. A few days earlier, Josef Stalin (1878–1953) and Lev Kamenew (1883–1936) had spoken out in Pravda in favor of moving the Provisional Government to start peace negotiations. Until then, you have to "answer every ball with a ball". Lenin sharply criticized them for this attitude, which corresponded roughly to the "revolutionary defensism" represented by the majority of the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries.

At the First All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers 'and Soldiers' Deputies in early June 1917, Lenin's radical demands met with incomprehension from the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries, who had a clear majority (the Bolsheviks only had 105 of the 822 voting deputies). Lenin defended them and stressed that the Bolsheviks were "ready at any minute to take over total power." In doing so, he made it clear that behind the demand for council rule stood for rule by his own party, even if it was in the minority.

German money payments

During the First World War, the German Reich supported the opposition to the Tsarist regime with monetary payments . For example, on April 1, 1917, the Foreign Office applied to the Reich Treasury for five million marks “for political propaganda in Russia”. Whether and to what extent the Bolsheviks benefited from this is disputed in research. The so-called Sisson documents , which were published in the American press on September 15, 1918, form the basis of the supporting thesis . According to the judgment of the American historian George F. Kennan in 1956, however, these are fakes.

The Russian historian Dmitri Wolkogonow is one of the proponents of the thesis that the Bolsheviks are subsidized by the German Reich . However, the British historian Orlando Figes considers its evidence to be “unconvincing” and considers it absurd to call the Bolsheviks “German agents ” for this reason .

The British historian Robert Service also points out that several million marks flowed from the German government to socialists in Russia. He sees the massive expansion of the Bolsheviks' party press in the days of the revolution as an indication that they profited from the payments. The historian Oleh Fedyshyn also notes the payments to Russian socialists and describes the Bolsheviks as the main beneficiaries. It gives estimates by other historians from 20 to 50 million Reichsmarks.

The American historian Alexander Rabinowitch , on the other hand, uses relevant sources to point out “that most of the Bolshevik leaders, and the party base anyway, knew nothing of these financial contributions. While Lenin seems to have known about the German money, there is no evidence that his or the party's policies were influenced by it. In the end, this aid did not have a decisive influence on the outcome of the revolution. "

The German historian Gerd Koenen believes that the Bolsheviks received the majority of German subsidies: Their central organ Pravda has been able to increase its circulation to 100,000 since March 1917 and also issue several special editions for the various branches of service, the circulation of which was sufficient for every company in the whole to send one copy to the Russian military. At the same time he doubts that Lenin could be called a German agent for this reason. Rather, there was at times a parallel interest between him and the Reich leadership.

Increase in power of the Bolsheviks

In the course of the occupation of the factory, under the influence of the Bolsheviks, in some cases also anarchists , the workers' paramilitary self-protection units emerged, the Red Guards . By June 1917 they trained higher command structures, in Petrograd alone they comprised 20,000 armed men. After the failure of the Kerensky offensive in July 1917, in Lenin's absence (he was in Finland for recreation) and perhaps inspired by his claim to power at the 1st All-Russian Congress, they undertook an improvised attempt at insurrection, the so-called Juliet Uprising, which was quickly taken over by government troops was shot down. The Provisional Government arrested numerous Bolsheviks, including Leon Trotsky (1879–1940), who was accepted into the party in August 1917 while he was still in custody. Lenin, who had returned to Petrograd during the uprising and gave a short speech, changed his appearance by shaving and wearing a wig and went into hiding in Finland. The government used the uprising to portray the Bolsheviks as secret allies of the approaching German troops. To this end, she distributed a list of the names of those arrested, almost all of whom sounded German or Jewish: this was intended to create the impression that the whole party of the Bolsheviks consisted only of German Jews. In this way she contributed to the emergence of the conspiracy theory of allegedly purely Jewish Bolshevism .

The situation changed on August 27th July. / September 9, 1917 greg. by the right-wing coup attempt by General Lawr Kornilov (1870-1918), whom Kerensky had appointed as commander in chief of the Russian troops in July . Inadequately prepared, the Kornilov putsch quickly failed. The telegraph operators refused to relay the general's orders and the railroad workers refused to send his troops to the capital. However, Kerensky had to ask the Red Guards and units from the army and navy close to the Bolsheviks for help. In Petrograd they were ready to repel the putschists if necessary. The government of Prince Lvov resigned, War Minister Kerensky now also took over power in an emergency dictatorship as Prime Minister with a "Directory" of five ministers . But the Bolsheviks now stood there as defenders of the revolution and turned the government propaganda around. They now claimed that it was Kerensky who was in league with the Germans. A separate peace between the German Reich and Great Britain was imminent; Kerensky had already arranged the surrender of Petrograd and Kronstadt with them . The result was another shift to the left, particularly among the urban population. In the new elections to the Soviets of Moscow and Petrograd in September 1917, the Bolsheviks won clear majorities in both bodies, and Trotsky assumed a key position as chairman of the Petrograd Soviet and its executive committee. In late August and early September, the Soviets passed resolutions in over eighty cities in Russia calling on the Provisional Government to hand over “all power to the councils”.

In the elections to the Petrograd city parliament, the Bolsheviks had July 7th . / August 20, greg. 33.4% won and had become the second largest party behind the Social Revolutionaries. With their demands for Soviet rule and "bread, peace and land" they gained popularity. Viewed across the country, they still remained in the minority: at the Democratic Conference convened in September, to which exclusively revolutionary forces were allowed, they provided only 134 of 1200 delegates. Here, too, the largest faction was formed by the Social Revolutionaries with 532 delegates, 71 of them from their left wing .

The coup

preparation

In the leadership of the Bolshevik Party it was controversial whether they should take part in the elections to the Constituent Assembly or instead opt for a violent uprising . Lenin, in his Finnish hiding place, urged the party to take sole power of government, considering the time was right to take advantage of the government's weak position. In a letter in mid-September he wrote:

“It would be naive to wait for a 'formal' majority of the Bolsheviks. No revolution waits for this. Kerensky and Co. do not wait either, they are preparing to extradite Petrograd [to the Germans]. It is precisely the pathetic fluctuations in the Democratic Conference that must and will rattle the patience of the workers in Petrograd and Moscow! History will not forgive us if we do not seize power now. "

Most of the other leading Bolsheviks, however, were in favor of letting power pass democratically to the Soviets, and wanted to wait for the II All-Russian Congress of Soviets to be held on October 20th . / November 2, 1917 greg. was convened. Although the Central Committee had ordered him to stay in Finland, Lenin returned on October 9th jul. / October 22nd greg. secretly back to Petrograd. Two Central Committee meetings on 9 jul. / October 22nd greg. and on 15 jul. / October 28th greg. he was able to pull the majority of the party leadership on his side: only Grigory Zinoviev (1883-1936) and Kamenev opposed him , who denied that the conditions for a socialist revolution were already in place and feared that an uprising that began too early would be suppressed . Lenin angrily replied that it would be necessary to wait for "perfect idiocy or perfect betrayal". One should “not be guided by the mood of the masses, it is fickle and cannot be calculated precisely”. Rather, it is a matter of confronting the All-Russian Congress with a fait accompli and legitimizing the revolution through it . The Central Committee finally passed a resolution with nineteen votes against two, which obliged all party cadres to “prepare the armed insurrection from all sides and vigorously”. To organize the uprising, a center was formed from Andrei Bubnow (1883-1938), Felix Dzerzhinsky (1877-1926), Moissei Urizki (1873-1918), Jakow Sverdlov (1885-1919) and Josef Stalin . A date was not mentioned, "the day of the uprising", Stalin is said to have said, "the circumstances determine". On jul. / October 29th greg. Date of the II All-Russian Congress of Soviets of moderate socialist groups became on October 25th July. / 7th November 1917 greg. postponed. They apparently wanted to give Kerensky time to take action against the Bolsheviks beforehand. Without this postponement, however, Lenin's intention to take power before the meeting of the Soviet Congress could not have been implemented.

However, this military-revolutionary center was only symbolic. The real strategist of the coup was Leon Trotsky. By decision of the Petrograd Soviet he had July 8th . / October 21, 1917 greg. set up a military organization, the Military Revolutionary Committee (MRK). Lenin later wrote:

"After the Petrograd Soviet passed into the hands of the Bolsheviks, Trotsky was elected chairman, and in this capacity he organized and directed the uprising of October 25th."

Pro forma the HRC was supposed to prepare the defense of the city against a counter-revolution , in truth it served to thwart the transfer of revolutionary troops to the front, which Kerensky had ordered a few days before. The soldiers did not see this as a contribution to the defense of the fatherland, but as an attempt to remove revolutionary elements from Petrograd. The HRC became the instrument of the Bolsheviks' military seizure of power. The troops were limited to around 15,000 to 20,000 soldiers from the Petrograd garrison , the Kronstadt navy, who were subordinate to the Military Revolutionary Committee, the Red Guards and a few hundred militant Bolsheviks from the workers' committee. According to other sources, they only had 6,000 men.

On October 22nd, Jul. / November 4, 1917 greg. the troop commander of the Petrograd district refused to submit his staff to the control of the commissioners of the HRC. Thereupon, at the instigation of Trotsky and Sverdlov, it took over the command of the garrisons of the capital. From then on, the Military Revolutionary Committee inspected all barracks, weapons depots and staff units in the city, and all military orders had to be countersigned by it. The von Kerensky on October 20, Jul. / November 2, 1917 greg. Ordered troop relocation was prevented.

Military coup

Kerensky was aware that the Bolsheviks and the HRC were now asking the question of power openly. As a first countermeasure, he ordered jul on the night of October 24th . / November 6, 1917 greg. the closure of all Bolshevik printing works. With this he gave Trotsky the excuse to strike. On this day, units of the MRK, supported by the Red Guards, occupied strategic points in the city. That was only noticed during the course of the day, when it was reported to the commandant's office that no more orders were being carried out. Kerensky then fled to the headquarters in Tsarskoye Selo to organize loyal troops to regain power. There he fell on deaf ears because several of the generals loyal to the Tsar were hoping for a Bolshevik putsch that would soon collapse and clear the way for a dictatorship they wanted .

Meanwhile, at a meeting of the Petrograd Soviet at the Smolny Institute , Trotsky and Lenin declared that the Kerensky government had been overthrown, that power was in the hands of a Revolutionary Military Committee and that the "victorious uprising of the proletariat of the world" was imminent. During the day, the first posters also provided information about the change in power. Around the Winter Palace , where the remnants of the Provisional Government met, there were some exchanges of fire, with which the loyal soldiers also fended off looters. During the night, a blind shot was fired at the seat of government from the Peter and Paul fortress on the other bank of the Neva , and the cruiser Aurora fired shots without causing any lasting damage to the building. When it became clear in the course of the night that resistance was no longer to be expected, members of the MRK occupied the Winter Palace, which they entered through the unlocked main gate. They arrested the assembled ministers and later released them after signing a declaration that they would withdraw from politics. The officer students gathered to protect them were sent home against an assurance of goodwill. Some members of a women's battalion, who were accused of having shot at the HRC members, were imprisoned, abused, and some were raped. The city was then completely in the hands of the Bolsheviks.

The name "Storm on the Winter Palace", which is kept in the collective memory, goes back to the bestseller Ten Days That Shook the World by the American journalist John Reed , who was present at the arrest of the members of the government. It was supposed to put the October Revolution in line with the French Revolution with the Bastille Tower , but it represents a strong dramatization of the overall unspectacular action.

The coup in Moscow was less peaceful, where the Bolsheviks were only able to prevail after a week of bloody fighting. Several hundred people were killed and part of the Kremlin was damaged. The decisive factor here, too, was the passive behavior of the garrison, which refused to take up arms for the February regime. In the rest of the country, the change of power was just as peaceful as in Petrograd, as local groups of the Mensheviks and the Social Revolutionaries were often willing to work together.

The II All-Russian Congress of Soviets

At the II All-Russian Congress of Soviets (II Russian Всероссийский съезд советов ; transcription : Vtoroi Vserossijski sjesd sovietow ), which, after some temporization by Lenin, took place on the late evening of October 25th . / 7th November 1917 greg. opened, the Bolsheviks held 300 of the 670 seats. The Social Revolutionaries provided 193 delegates, many of whom belonged to the left wing of the party, which cooperated with the Bolsheviks. The Mensheviks had 82 seats and the remaining delegates belonged to smaller socialist groups. The overwhelming majority, namely 505 delegates, agreed to the slogan “All power to the councils!” On a questionnaire distributed in advance, but it was by no means certain whether this would also go hand in hand with the military action of the Bolsheviks. The Menshevik and Socialist Revolutionary delegates who opposed this disagreed with each other and made it easy for the Bolsheviks by adopting a boycott strategy: In protest, the Mensheviks renounced their right to take the four seats they were entitled to on the Congress Bureau, ultimately always leaving more Menshevik and Social Revolutionary groups of delegates protested the assembly hall. The typists also stopped working, which is why there are no minutes of the Congress. Trotsky mocked the Menshevik politician Martov:

“The uprising of the masses needs no justification. What happened was a riot, not a conspiracy. […] The masses followed our banner and our uprising was victorious. And now they are proposing to us: renounce your victory, declare your willingness to make concessions, make a compromise. With who? I ask: who should we compromise with? With pathetic groups that have gone out or are making this suggestion? [...] Nobody stands behind them in Russia anymore. No, no compromise is possible here. We must say to those who have gone out and those who propose to us: you are pathetic bankrupts, your role is played out; go where you belong: on the rubbish heap of history! "

In the late evening Lenin appeared, whom most delegates saw for the first time in their lives. He read the so-called revolutionary decrees: the decree on peace , which offered the immediate start of negotiations on a “just peace” on the condition of a general renunciation of annexations and war compensation , and the decree on land , which expropriated and expropriated large estates without compensation thus legitimized land appropriation by the peasants, which for the most part had already taken place. The delegates, to whom the texts had not been submitted in writing, agreed unanimously or with a large majority. On the morning of October 26th, Jul. / November 8, 1917 greg. Congress also acclaimed the decree on the establishment of the Council of People's Commissars , the new Russian government, of which Lenin became head. The assembly sang the Internationale and parted.

After the coup

Council of People's Commissars

The Council of People's Commissars (Russian Совет Народных Комиссаров; Soviet Narodnych Komissarow, or Sownarkom for short) should, according to the decree that set it up as government, act in a grassroots , non-bureaucratic and flexible manner. For this he should rely on "commissions" that should provide the technical expertise, and be responsible to the All-Russian Congress of Soviets and its executive committee. In reality, these commissions were never set up. Instead, the People's Commissars moved into the ministries that had existed until then and largely took over their civil servants. More than half of the employees and officials in the Sovnarkom authorities had worked there before the October revolution. There was also no effective control by the Soviets. Instead, the People's Commissars followed the guidelines of the Bolshevik Party, which was not even mentioned in the founding decree.

The Sownarkom initially consisted only of Bolsheviks. Trotsky ( external affairs ), Stalin ( nationality issues ), Alexei Rykow (1881–1938; internal affairs), Vladimir Miljutin (1884–1937; agriculture) and Vladimir Antonov-Ovsejenko (1883–1938), Nikolai Krylenko (1885–1938) took over important departments. and Pawel Dybenko (1889–1938): the latter three were collectively responsible for the military and navy. After successful coalition negotiations, July 9th moved forward. / 22nd December 1917 greg. seven left SRs in government. Lenin and the People's Commissars went to work with great enthusiasm - by the end of 1917 alone they had issued 116 different decrees. Most of them were handwritten by Lenin himself. From 1917 to 1922 he is said to have written, dictated or edited a total of 676 laws, decrees and instructions, an "unbelievable workload", as Gerd Koenen comments.

- On October 27th, Jul. / November 9, 1917 greg. which was censorship reintroduced. The Sownarkom passed the Decree on the Press , which provided for the closure of all newspapers that called for disobedience to the new government. That was tantamount to banning all press organs of the non-socialist parties in Russia.

- In the decree on workers' control of November 1st jul. / November 14, 1917 greg. the control of the industrial plants by the workers was established. Since the planned cooperation between companies and workers did not work, unlike in the text of the decree, nationalizations were the result. This process was already completed in mid-1918, and since then all industrial companies in Russia have been state-owned.

- In the Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia of November 2, Jul. / November 15, 1917 greg. all peoples of Russia were granted the right to self-determination ; all forms of national and religious discrimination were abolished.

- On November 2nd, Jul. / November 15, 1917 greg. became the privileges of all Christian confessions and on December 11th jul. / December 24, 1917 greg. the religious instruction abolished in schools. On January 20th jul. / February 2, 1918 greg. followed the law on the separation of state and church. After a short and relatively calm consolidation phase, all denominations and religious communities were massively persecuted. The security authorities arrested numerous pastors, committed lay people and ordinary believers; a large number of them died in camps, among other places. See also Religion in the Soviet Union .

- On November 24th July / 7 December 1917 greg. The Extraordinary Commission for the Struggle against Counterrevolutionaries and Sabotage (abbreviation: Cheka ) was founded under the leadership of Dzerzhinsky. The aim of this secret police was to eliminate the political opposition through terrorist violence and to enforce the party's monopoly on power across the country. She worked for the so-called revolutionary tribunals, as she was not allowed to pass or enforce any judgments until the decree of September 26, 1918. Soon it was used not only against the opposition, but also against speculation and corruption .

- A decree dated November 28th jul. / December 11, 1917 greg. ordered the leaders of the Cadets, the only non-socialist party to have mass supporters, to be arrested “as a party of enemies of the people ”.

The dissolution of the Constituent Assembly

Although the Bolsheviks could not be sure of obtaining a majority, they set the constituent assembly elections for October 29th July. / November 11, 1917 greg. firmly. These should originally have taken place in September, but the Provisional Government had postponed them, from which the propaganda of the Bolsheviks had benefited argumentatively. Lenin had already spoken out in favor of postponing the elections again on the day of the coup, but had been overruled by the Central Committee and the Executive Committee.

In the elections, 48.4 million votes were cast, the turnout is estimated at around 60%. The Social Revolutionaries were the strongest party with 19.1 million votes, followed by the Bolsheviks with 10.9 million votes - the greatest electoral victory in their history, but a heavy defeat, because more than half of the electorate cast suspicion on the ruling party. The Cadets received 2.2 million votes, the Mensheviks 1.5 million, and the non-Russian socialist parties more than 7 million votes, most of them from Ukraine. After a demonstration by a "Committee for the Defense of the Constituent Assembly" was shot down by Kronstadt sailors on the order of Dybenko in the morning, the Constituent Assembly entered into jul. / January 18, 1918 greg. together in the Tauride Palace. The MPs rejected the Bolsheviks' proposal to accept Soviet power for granted and instead followed an agenda proposed by the Socialist-Revolutionaries. Its founder Viktor Tschernow (1873–1952) was elected President of Parliament. A continuation of their work was prevented the following day by armed force by the Bolshevik military. In its decree of January 6th, Jul. / January 19, 1918 greg. to the now organizational split of the Left Social Revolutionaries, who were part of the coalition government, from the rest of the party: at the time of the election, the people could not distinguish between the two. In addition, only class institutions like the Soviets, but not representatives of all citizens of the nation, are able to "break the resistance of the possessing classes and lay the foundations of socialist society".

The establishment of Bolshevik autocracy

Since council rule was a very popular idea, it was fairly easy to expand over much of the country. Where the Bolsheviks could not count on a self-contained industrial working class, as in Petrograd, Moscow or in the mining districts of the Urals , they relied on the garrisons. The spread of the revolution in rural areas, where the village soviets competed with the traditional self-governing units , the zemstvos , in which social revolutionaries dominated , proved more difficult . By the beginning of spring 1918 there were Soviets in over 80% of all towns in Russia. The seizure of power by the local soviets combined with the socialization of the means of production and the elimination of real or suspected opponents. The unruly violence that accompanied this process was wanted by the Bolsheviks. This is what Lenin described in December 1917 in his posthumously published work How to organize the competition? the common goal is to “ clean the Russian earth from all vermin , from the fleas - the crooks, from the bedbugs - the rich, etc. etc.”. The manner of this cleaning could be very different:

“In one place, ten rich people, a dozen crooks, half a dozen workers who avoid work [...] will be put in prison. They'll have them clean the toilets somewhere else. At a third place they will be given yellow passports after they have served their sentence, so that the whole people will monitor them as harmful elements until they are bettered. In a fourth place, one in ten who are guilty of parasitism will be shot on the spot. "

In the late winter of 1918, the coalition of the Bolsheviks, which had recently been renamed the Communist Party of Russia (B) , fell apart with the Left Social Revolutionaries. The occasion was the dispute over the peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk , which the People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs Trotsky had signed on March 3, 1918 - a dictated peace that led Russia to unilaterally demobilize its army and renounce its Finnish, Courland , Lithuanian , Polish and Ukrainian Demanded areas. In doing so, it lost more than a third of its population, its agricultural area and its railroad network as well as three quarters of its deposits for coal and iron ore as well as practically all of its developed oil deposits and cultivation areas for cotton. This no longer seemed acceptable to the patriotic Left Social Revolutionaries. After they had not been able to assert themselves against the Bolsheviks at the 5th All-Russian Congress of Soviets, which met in the Bolshoi Theater on July 4, 1918 (in March 1918 the Sovnarkom had moved the capital to Moscow before the advancing German troops), they returned back to the method of individual terror that had characterized the Social Revolutionaries before 1917. On July 6, 1918, they murdered the German ambassador Wilhelm von Mirbach-Harff and thus triggered the uprising of the Left Social Revolutionaries , which was bloodily suppressed and led to the party being banned.

Moderate Social Revolutionaries and Mensheviks had already been declared counterrevolutionary by the Central Executive Committee of the Soviets on June 14, 1918, after which members of these parties were excluded from all Soviet organs. That was tantamount to banning these parties: from the summer of 1918, Russia was a one-party regime .

On July 8, 1918, the III. All-Russian Congress of Soviets a constitution for Soviet Russia . It was only intended to apply for a transitional period and was based on a draft by Lenin in January 1917. Russia was declared a federal republic of the Soviets of Workers', Soldiers' and Peasants' Deputies, to which all state power belonged. There was no separation of powers. Article 9 stipulated:

"The main task [...] consists in the establishment of the dictatorship of the urban and rural proletariat and the poorest peasantry in the form of the powerful all-Russian Soviet power to completely suppress the bourgeoisie , to abolish the exploitation of man by man and to establish socialism, under which there will be neither a division into classes nor a state power. "

The right to vote was valid regardless of origin, religion or gender, but was limited to people who “earn their living from productive and socially useful work” or who do. The Sovnarkom acted as the executive , whose decisions could be suspended at any time by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. How far it was with this distribution of power, however, showed a circular from the Bolsheviks of May 29, 1918: “Our party is at the head of Soviet power. The decrees and measures of the Soviet power emanate from our party. "

Civil war

The Russian Civil War had already begun in January 1918 with the uprising of the Don Cossacks under General Alexei Kaledin (1861-1918). In it national, political, social and religious lines of conflict overlap to create an economic and humanitarian catastrophe of unprecedented proportions. Between 1918 and 1922, 12.7 million people died on the territory of the former Russian Empire, compared to 1.85 million in World War I. More than half of the civil war victims died of starvation or epidemics . A main group of victims were the Jews in Russia , who were persecuted and murdered mainly by opponents of the Bolsheviks. It is estimated that around 125,000 people fell victim to these pogroms . Over 20,000 Jews emigrated to Palestine ( "Third Aliyah" ).

Russia disintegrated into various unstable units that were at war with one another, the brutalization was general on all sides. The national divisions in the West and on the Caucasus should be mentioned here, German troops penetrated as far as Kharkov , the Social Revolutionaries established their own brief territory ( Komutsch ) in Samara on the Volga , anarchists around Nestor Machno (1888–1934) defended one for several years " Free Rayon " in Eastern Ukraine, Green Armies and the farmers of Tambov fought against the forced seizure of grain as part of war communism , the Czechoslovak legions fought their way along the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok , British , French , American and Japanese intervention troops occupied the ports of Odessa , Vladivostok, Murmansk and Arkhangelsk . The decisive centers of power, however, were the "red" rulership of the Bolsheviks in central Russia and the areas ruled by the " whites " in southern Russia and Siberia . These were right-wing military leaders such as Anton Denikin (1872–1947), Alexander Kolchak (1874–1920), Pjotr Wrangel (1878–1928) or Nikolai Yudenitsch (1862–1933), who sought a restoration of the monarchy or a military dictatorship . Because they were at odds with one another, did not want to make firm commitments to the rural population on the agricultural issue and because of the weak infrastructure of the areas they ruled, they were structurally inferior to the “Reds”.

A major factor in the victory of the Bolsheviks was the establishment of the Red Army , which Trotsky established from January 1918. In doing so, he resorted to former tsarist officers as advisors, whose families he had taken hostage in order to ensure their loyalty. On May 29, 1918, conscription was reintroduced, badges of rank, military forms of greeting, disciplinary punishments up to the death penalty were added. Trotsky turned out to be a gifted military strategist who hurried from theater to war on his famous train, taking advantage of the inner line .

The Red Terror , which the Sownarkom decided on September 5, 1918, proved to be another success factor . The reason for this was two attacks . On August 30, 1918, Moissei Uritski , who had resigned from Sovnarkom in protest against the peace of Brest-Litovsk and now worked as the Cheka boss of Petrograd, fell victim to the bullets of a former cadet who was taking revenge for the execution of friends wanted to; At the same time, Lenin narrowly escaped a revolver attack perpetrated on him by the Social Revolutionary Fanny Kaplan . The Sovnarkom then declared it necessary “to free the Soviet republic from class enemies, which is why they should be isolated in concentration camps . All persons who are related to White Guard organizations, conspiracies and insurrections are to be shot ”. The Cheka's apparatus of repression was expanded, and its extrajudicial powers were expanded. The death penalty, which the Bolsheviks, like all socialist parties, had consistently rejected until then, became the normal means of suppressing class enemies, and this term included not only industrialists, large landowners, priests or cadets, but also workers and peasants. The decision remained in force until 1922, and it is estimated that several hundred thousand people fell victim to the Red Terror .

During the Civil War period, the new government also waged wars against Poland , Finland (January 27 to May 5, 1918) and Latvia . After the end of the civil war, the independent power of the Soviets was not restored, whereas in March 1921 the Kronstadt sailors' uprising turned. The sailors who had been on the side of the Bolsheviks during the revolution now demanded free elections to the Soviets and the restoration of freedom of speech , freedom of the press and freedom of association . The Bolsheviks portrayed the rebellion as a White Guard conspiracy controlled from abroad and had it bloodily suppressed by the Red Army. In an unprecedented criminal court, hundreds of Kronstadt sailors were shot on the spot, over 2,000 were sentenced to death, thousands received prison terms or were sent to the newly established camps in Kholmogory or on the Solovetsky Islands . 2500 civilians from Kronstadt were exiled to Siberia.

At the end of the civil war, the Bolsheviks had succeeded in regaining most of the secessionist territories. In 1922 they ruled 96% of the territories of the Russian Empire. In December 1922, a new state was founded on this territory that was to stamp the 20th century as a superpower : the Soviet Union .

reception

Whether what happened in Russia in October 1917 could be called a revolution was controversial from the start. On the night of October 26, 1917, the Mensheviks called the actions of the Bolsheviks simply a conspiracy . Because of the ease and resistance with which power in Petrograd passed into the hands of the Bolsheviks, the Menshevik Nikolai Sukhanov (actually Nikolai Nikolajewitsch Himmer) said it was really just a changing of the guard .

In Marxist-Leninist historiography, however, the events of the “Great October Socialist Revolution” (Russian: Великая Октябрьская Социалистическая Революция) were hyped up. The celebration of the annual return of the date, which was celebrated with large parades on Red Square , served to maintain this founding myth of the Soviet Union . The “Red October” was also repeatedly glorified in the creative arts and literature.

The stylization and dramatization of events began early on. On the third anniversary of the revolution, the director Nikolai Jewreinow staged a mass spectacle with 10,000 actors. This is where the idea of the “Storm on the Winter Palace” came from, which turned the rather unspectacular arrest of the Provisional Government into a dramatic battle that has gone down in collective memory. A photo of this staging (see picture on the right) was repeatedly used as an illustration of the events from 1922 onwards. A few years later the movie anchored in October by Sergei Eisenstein from 1927 the "storming of the Winter Palace" final in the collective memory. Here, however (historically correct) this takes place at night, not during the day as in Jewreinov's production; however, a wrought-iron gate is attacked in the film, which in truth only leads to the palace's outbuildings. In fact, the building was damaged more severely in the filming than in the actual events ten years earlier. Even in the times of glasnost and perestroika , the Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev celebrated the memory of October 1917:

“Those legendary days that ushered in a new era of social progress, the true history of mankind. The October Revolution was indeed a great moment for mankind, its dawn. The October Revolution was a revolution of the people and for the people, for the people, for their liberation and development. "

The contemporary of the revolutionary epoch and one of the spokesmen of the Russian socialists Maxim Gorky throws a critical light on the consequences of the events in his speech on the anniversary of the February revolution and characterizes the Russian revolution more as an uproar than as a revolution:

“A revolution is only sensible and great if it is the natural and powerful outbreak of all the creative forces of a people. However, if it only frees those feelings and thoughts that have built up in the people during their enslavement and oppression, if it is only an outbreak of bitterness and hatred, then we will not have a revolution, but an upheaval that will not change our lives can and only increases the cruelty and evil. Can we assert with a clear conscience that in the year of the revolution the Russian people, who freed themselves from the violence and anger of the police and official state, would have become better, friendlier, wiser, more honest as a result? No, if you are honest you wouldn't say that. We continue to live as we lived in the monarchy, with the same customs, habits and prejudices, just as stupid and filthy. […] The Russian people, who have achieved full freedom, are not able to use their great blessing for themselves, but only to abuse them to the detriment of themselves and their neighbors, and so they risk finally losing what they are has fought after painful centuries. Little by little, all the great things that his ancestors have worked out will be destroyed, the national riches will disappear and the opportunities to increase the treasures of this earth will be destroyed, industry, traffic and mail will be destroyed and the cities that are sinking in dirt. "

In Western history and political science, however, the October Revolution is often interpreted as a coup . The British historian Orlando Figes, for example, calls the events of October 1917 a "military coup" which "was not even noticed by the majority of the residents of Petrograd": a maximum of 25,000 to 30,000 people actively participated in the action - just under 5% of all workers and City soldiers. The historian Manfred Hildermeier also points out that the number of active participants in the October Revolution "was remarkably small". He finds it even more remarkable that the Bolsheviks did not immediately lose the power they had once gained in the crisis years 1918 to 1920. He calls this assertion of power “the second revolution”. The German political scientist Armin Pfahl-Traughber also calls the October Revolution a putsch and not a revolution in the narrower sense:

“Although the result was fundamental social change, the revolution itself did not take place with the participation of the masses. The takeover of power succeeded through the paralysis of the other political forces and through the well-planned action of the insurgents. "

The British political scientist Richard Sakwa sees several revolutions in the October Revolution: six revolutions would have overlapped in a complex process: the social mass revolution, a democratic revolution, the anti-elitist revolution of the Russian intelligentsia , the national revolution of the minority peoples within the tsarist empire, the Revolution of the Marxist thesis that only a society with fully developed capitalism could produce a revolution, and finally the revolution within the revolution, in which the Bolsheviks usurped the agenda of all other socialist groups and thus established their dictatorship.

Under Vladimir Putin , the attitude towards the October Revolution changed radically. Putin accused the revolutionary leader of plunging Russia into a devastating civil war and thus dividing the Russian people. Lenin is responsible for the "destruction of statehood" and "millions of human fates". Putin connects the real essence of this historical event, namely its revolutionary form, with chaos, disorder and instability, because he regards these as an immediate danger to the existing political system in today's Russia.

Movie and TV

- Lenin in October (USSR 1937, directed by Michail Romm )

- Tsar to Lenin (USA 1937, directed by Max Eastman )

- Civil War in Russia (TV-FRG 1967/68, 5 parts, director: Wolfgang Schleif )

literature

- Riccardo Altieri: The October Revolution 1917. In: Riccardo Altieri, Frank Jacob (Hrsg.): The history of the Russian revolutions. Hoped for change, experienced disappointment, forced adaptation. minifanal, Bonn 2015, pp. 240-280, ISBN 3-95421-092-4 .

- October Revolution (PDF; 2 MB). In: From Politics and Contemporary History . 44-45 / 2007.

- Jörg Baberowski , Robert Kindler, Christian Teichmann: Revolution in Russia 1917–1921 . State Center for Political Education Thuringia, Erfurt 2007.

- Jörg Baberowski: What was the October Revolution? In: Federal Center for Political Education (ed.): Politics and contemporary history . No. 44–45 , 2007 ( bpb.de [accessed December 3, 2008]).

- Orlando Figes : A People's Tragedy . Berlin Verlag, Berlin 1998.

- Manfred Hellmann (ed.): The Russian Revolution 1917. From the abdication of the Tsar to the coup d'état of the Bolsheviks . Deutscher TB Verlag, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-423-02903-X .

- Manfred Hildermeier: Russian Revolution . Fischer Kompakt, Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt 2004, ISBN 3-596-15352-2 .

- Manfred Hildermeier: The Russian Revolution 1905-1920 . 4th edition. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1995.

- Gerd Koenen : The color red. Origins and history of communism. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2017.

- Alexander Rabinowitch : The Soviet Power: The Revolution of the Bolsheviks 1917 . Mehring Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-88634-097-2 .

- Steve A. Smith : The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-15-018703-6 .

- Isaak Steinberg : Violence and Terror in the Revolution. The Fate of the Humiliated and Offended in the Russian Revolution . Karin Kramer Verlag, Berlin 1981 (written by a Left Social Revolutionary between 1920 and 1923).

Web links

- 100 years of the Russian Revolution - November 7, 1917. Political education, information portal on political education

- October 25 (November 7), Wednesday. Protocol of a day that shook the world. In: Trend online newspaper

- Manfred Hildermeier : Lenin's contempt for the philistine talk. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . 7th November 2017

- “Peoples, hear the signals!” 100 years of the October Revolution. In: Deutschlandfunk Nova . November 10, 2017

Individual evidence

- ^ According to information from the Federal Archives, the SED and authorities in the GDR used the abbreviation GSOR .

- ^ Christian Th. Müller, Patrice G. Poutrus: Arrival, everyday life, departure. Migration and intercultural encounters in GDR society . Cologne / Weimar 2005, p. 35 ( limited preview in Google Book Search - the acronym GSOR was also in use in the GDR ).

- ↑ Steve A. Smith : The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 30.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier : The Russian Revolution 1905-1921. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, pp. 140 f.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier: The Russian Revolution and its consequences. In: From Politics and Contemporary History . 67, Heft 34-36 (2017), p. 12, accessed on October 21, 2017.

- ↑ Herfried Münkler : The Great War. The world 1914–1918. Rowohlt, Berlin 2013, p. 616.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier: The Russian Revolution 1905-1921. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, pp. 193-203.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen : The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 728.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier: The Russian Revolution 1905-1921. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, p. 119 f. and 191 f.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism . Beck, Munich 2017, p. 728.

- ↑ Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, pp. 41–46.

- ↑ Vladimir I. Lenin: The War and Russian Social Democracy. In: the same: works. Volume 21, Berlin (East) 1960, p. 19, quoted in Gerd Koenen: Spiel um Weltmacht. Germany and the Russian Revolution. In: From Politics and Contemporary History. 67, Heft 34-36 (2017), p. 15, accessed on October 21, 2017.

- ↑ Christopher Read: Lenin . Abingdon 2005, p. 140 .

- ↑ Orlando Figes : The Tragedy of a People. The epoch of the Russian Revolution from 1891 to 1924. Goldmann, Munich 2001, p. 411.

- ↑ Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 38 f .; Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, pp. 716–719 and 724 f.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier: The Russian Revolution 1905-1921. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, p. 174 f.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 740.

- ↑ George F. Kennan : The Sisson Documents. In: Journal of Modern History. 1956, pp. 130-154.

- ↑ Dmitri Volkogonow : Lenin. Utopia and terror . Düsseldorf 1994, p. 118-125 .

- ↑ Orlando Figes: The Tragedy of a People. The epoch of the Russian Revolution from 1891 to 1924. Goldmann, Munich 2001, pp. 411 and 900 (note 48).

- ^ Robert Service : Lenin. A biography . Munich 2000, p. 387 f .

- ↑ Oleh S. Fedyshyn: Germany's Drive to the East and the Ukrainian Revolution 1917-1918 . New Brunswick 1971, p. 47 .

- ↑ Alexander Rabinowitch : The Soviet Power - The Revolution of the Bolsheviks 1917 . Essen 2012, p. 20 .

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 740 f.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism . Beck, Munich 2017, p. 728.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, pp. 737-741 and 745; Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 40 f.

- ↑ Björn Laser: Cultural Bolshevism! On the discourse semantics of the “total crisis” 1929–1933. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2010, p. 71.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier: The Russian Revolution 1905-1921. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, p. 222 ff.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 748.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 748 f.

- ↑ Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 53 f.

- ↑ Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 54.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier: The Russian Revolution 1905-1921. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, p. 224 ff.

- ↑ Manfred Hellmann (ed.): The Russian Revolution 1917. From the abdication of the Tsar to the coup d'état of the Bolsheviks. dtv, Munich 1980, p. 285.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 752; Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 55 f.

- ↑ Dimitri Volkogonow: Stalin. Triumph and tragedy. Econ, Munich 1993, p. 63.

- ↑ Leon Trotsky : Stalin. A biography. Arbeiterpresse Verlag, Essen 2006, p. 290.

- ↑ Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 56 f.

- ↑ Dimitri Volkogonow: Trotsky. The Janus face of the revolution . Berlin: edition berolina, 2017, ISBN 978-3-95841-085-5 , p. 125.

- ↑ "После того, как Петербургский Совет перешел в руки большевиков, Троцкий был избран его председателем, в качестве которого организовал и руководил восстанием 25 октября». Владимир Ильич Ленин: Собрание сочинений , Volume 14, Part 2. Moscow: Гос. изд-во, 1921; S. 482. German translation after Dimitri Wolkogonow: Trotsky. The Janus face of the revolution . Berlin: edition berolina, 2017, ISBN 978-3-95841-085-5 , p. 125.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 749; Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 56.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier: The Russian Revolution 1905-1921. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, p. 238.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 753.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 749.

- ↑ Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 57.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 753 f.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 754 f.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 755.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier: The Russian Revolution 1905-1921. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, p. 238.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier: The Russian Revolution 1905-1921. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, p. 239 f .; Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 755 f.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier: The Russian Revolution 1905-1921. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, p. 241.

- ^ Decree on Peace, October 26th (November 8th) 1917 at 1000dokumente.de , accessed on November 10th 2017; Orlando Figes: A People's Tragedy. The epoch of the Russian Revolution from 1891 to 1924. Goldmann, Munich 2001, p. 568; Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 62 ff.

- ↑ Decree of the 2nd All-Russia Soviet Congress on Land, October 26 (November 8) 1917 at 1000dokumente.de, accessed on November 10, 2017; Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 64 f.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 756 ff.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 807.

- ↑ Decree of the 2nd All-Russian Congress of Soviets on the Formation of the Workers 'and Peasants' Government, October 26 (November 8) 1917 on 1000dokumente.de, accessed on November 10, 2017.

- ↑ Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 65 f.

- ↑ Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 61.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 759 f.

- ^ Armin Pfahl-Traughber : Forms of State in the 20th Century. I: Dictatorial Systems. In: Alexander Gallus and Eckhard Jesse (Hrsg.): Staatsformen. Models of political order from antiquity to the present. A manual. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2004, p. 231.

- ↑ Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia on 1000dokumente.de, accessed on November 10, 2017.

- ↑ Stefanie Theis: Religiosity of Russian Germans. 1st edition. Kohlhammer, 2006, ISBN 3-17-018812-7 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Security organs of the USSR. In: Carola Stern , Thilo Vogelsang , Erhard Klöss, Albert Graff (eds.): Dtv-Lexicon on history and politics in the 20th century. dtv, Munich 1974, Volume 3, p. 732.

- ↑ Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 94.

- ↑ Decree of the Council of People's Commissars (SNK) on the arrest of the leaders of the civil war against the revolution, November 28 (December 11) 1917 on 1000dokumente.de, accessed on November 10, 2017.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 766 f.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 767; Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 67 f.

- ↑ Decree on the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly, January 6 (19) 1918 at 1000dokumente.de, accessed on November 10, 2017.

- ↑ Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 68.

- ↑ Such IDs actually identified prostitutes .

- ↑ Vladimir I. Lenin: How should one organize the competition? In: the same: works. Volume 26, Dietz Verlag, Berlin (East) 1972, p. 413, quoted in Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 765 f.

- ↑ Brest-Litovsk, Peace of. In: Carola Stern, Thilo Vogelsang, Erhard Klöss, Albert Graff (eds.): Dtv-Lexicon on history and politics in the 20th century. dtv, Munich 1974, Volume 1, p. 109; Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 64.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 792.

- ^ Armin Pfahl-Traughber: Forms of State in the 20th Century. I: Dictatorial Systems. In: Alexander Gallus and Eckhard Jesse (Hrsg.): Staatsformen. Models of political order from antiquity to the present. A manual. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2004, p. 231.

- ↑ Basic Law of the Russian Federal Socialist Soviet Republic (RSFSR) of July 10, 1918 ( Memento of November 5, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) on Verassungen.net, accessed on November 10, 2017; Harald Moldenhauer, Eva-Maria Stolberg: Chronicle of the USSR. Olzog, Munich 1993, p. 29; Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 772.

- ↑ Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 70 f.

- ↑ Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 71 f.

- ↑ Felix Schnell: The sense of violence. The Ataman Volynec and the permanent pogrom of Gajsin in the Russian Civil War (1919). In: Zeithistorische Forschungen / Studies in Contemporary History. Online edition, 5 (2008), issue 1. Retrieved on November 11, 2017.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, pp. 777-785; Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, pp. 73–81.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 759.

- ↑ Resolution of the Council of People's Commissars on the Red Terror, September 5, 1918 at 1000dokumente.de , accessed on November 11, 2017.

- ↑ Gerd Koenen: The color red. Origins and history of communism. Beck, Munich 2017, p. 817; Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 71 f.

- ↑ Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 92.

- ↑ Esther Knorr-Anders : Forgers in the service of politics. Faked and mounted photos for the people. In: The time . No. 43/1989.

- ↑ Vladimir N. Brovkin: The Mensheviks after October. Socialist Opposition and the Rise of the Bolshevik Dictatorship. Cornell University Press, Ithaca 1988, p. 17.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier: The Russian Revolution 1905-1921. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, p. 238.

- ↑ Sylvia Sasse: Retouching = attack. Or: How history was repaired through theater. In: The magazine. # 28, April 2017. Federal Cultural Foundation.

- ^ Dieter Krusche: Reclam's film guide. 7th edition, Philipp Reclam, Stuttgart 1987, p. 410 ff.

- ↑ Mikhail Gorbachev : The October Revolution and the Reshaping Process: The Revolution Continues. In: New Time . 45 (1987), p. 2 ff.

- ↑ Maxim Gorki, 1918. Excerpt from his speech on the anniversary of the February Revolution. First published by Orlando Figes: The Tragedy of a People. The era of the Russian Revolution, 1891–1924. Berlin 2011, p. 426.

- ↑ Steve A. Smith: The Russian Revolution. Reclam, Stuttgart 2017, p. 58.

- ↑ Orlando Figes: The Tragedy of a People. The epoch of the Russian Revolution from 1891 to 1924. Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2008, p. 512 and 521.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier: The Russian Revolution 1905-1921. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1989, p. 244 f .; see also Manfred Hildermeier: The Russian Revolution and its consequences. In: From Politics and Contemporary History. 67, Heft 34-36 (2017), p. 10, accessed on October 21, 2017.

- ^ Armin Pfahl-Traughber: Forms of State in the 20th Century. I: Dictatorial Systems. In: Alexander Gallus and Eckhard Jesse (Hrsg.): Staatsformen. Models of political order from antiquity to the present. A manual. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2004, p. 230; similar to Dietrich Geyer : The Russian Revolution. 4th edition, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1985, p. 106.

- ^ Richard Sakwa: Russian Politics and Society. 4th edition, Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon 2008, p. 4.

- ^ Wolfram Neidhard: The Bolshevik coup. n-tv , November 7, 2017, accessed January 1, 2018 .