Kharkiv

| Kharkiv | ||

| Харків / Харьков | ||

|

|

|

| Basic data | ||

|---|---|---|

| Oblast : | Kharkiv Oblast | |

| Rajon : | District-free city | |

| Height : | 152 m | |

| Area : | 306.0 km² | |

| Residents : | 1,446,107 (2019) | |

| Population density : | 4,726 inhabitants per km² | |

| Postcodes : | 61000-61499 | |

| Area code : | +380 572 | |

| Geographic location : | 50 ° 0 ′ N , 36 ° 15 ′ E | |

| KOATUU : | 6310100000 | |

| Administrative structure : | 9 Stadtrajone | |

| Mayor : | Henadij Kernes | |

| Address: | пл. Конституції 7 61200 м. Харків |

|

| Website : | http://www.city.kharkov.ua/ | |

| Statistical information | ||

|

|

||

Kharkiv ( Ukrainian Харків ; Russian Харьков Charkow ) is the second largest city in Ukraine after Kiev with around 1.5 million inhabitants (2019) and with 42 universities and colleges it is the most important science and education center in the country after Kiev.

The city is located in the northeast of Ukraine at the confluence of the Kharkiv River in the Lopan and the Lopan in the Udy . It is an industrial center (electrical, food, chemical industry; machine and rail vehicle construction). With six theaters and six museums, it represents a cultural center and is an important transport hub ( airport , railroad , underground ).

Name and spelling of the city

The official name of the city is Kharkiv ( Ukrainian ). In addition, Kharkov ( Russian ) is common in the largely Russian- or bilingual population . While it was part of the Soviet Union, the German-speaking media almost consistently used the Russian name variant. However, since the independence of Ukraine, the Ukrainian version of the name has been used increasingly. Occasionally, the spellings Kharkiv and Kharkov can also be found, which are based on the English transcription of the Ukrainian or Russian name.

For the actual linguistic situation in the city, where both Russian and Ukrainian are spoken, see section Population and Language .

The origin of the city name is controversial. Some are of the opinion that he either went to Sharukan (Sharuk-Khan), the capital of the Cumans supposedly located in the same place, but which fell into disrepair after the Mongol storm in 1223 or finally 1238, or to the legendary founder of the city, the Cossack Charko , goes back.

history

The city was originally founded as a fortress to defend the southern borders of Tsarist Russia in 1630, (according to other sources in 1653). The surrounding Sloboda-Ukraine , formerly part of the so-called Wild Field , was settled at this time by the Ukrainian peasants and Cossacks fleeing en masse from Poland-Lithuania as well as by Russian troops. Their function was, among other things, to ward off the regular predatory incursions of the Crimean Tatars into southern Russia. In peaceful times they practiced handicrafts and agriculture.

With the conquest of New Russia and the shifting of the borders to the south, Kharkiv lost its importance as a fortress at the end of the 18th century. However, the city became a center of handicrafts and trade after becoming the capital of Kharkov Governorate as early as 1765 . It was said of the Kharkiv fairs in 1864 that they were exceeded in terms of sales only by the fair in Nizhny-Novgorod and at Irbit .

In 1805 the University of Kharkov was opened. 28 German lecturers and professors were employed at the opening, including Johann Baptist Schad . In connection with the connection to the railway network (1869) and the beginning of the mining of coal and iron ore in Ukraine, Kharkiv became an important industrial center at the end of the 19th century. In 1906 the Kharkiv tram started operating.

During the civil war from 1917 to 1920 there was heavy fighting between opposition forces in the city. In January 1918, the first Ukrainian Soviet Congress met in Kharkiv, proclaiming Ukraine a Soviet republic and declaring Kharkiv its first capital, which it remained until 1934. In 1933 the city had 833,000 inhabitants.

In the spring of 1933, Kharkiv was one of the areas that was particularly badly affected by the Holodomor , a famine largely caused by the Stalinist regime . Over 45,000 people died of starvation in the city within a few months. In 1934 the capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic was moved to Kiev , but the city remained an important political, economic and cultural center.

In March 1940, over 3,000 Polish citizens were murdered in an NKVD prison in Kharkiv in connection with the Katyn massacre and buried in a wooded area near the Pjatychatky settlement in what is now the city of Kiev. In the late 1990s, the remains were transferred to the cemetery for the victims of totalitarianism .

During the Second World War , Kharkiv was a very important strategic object, not only because of the important transport hubs, but also because of the developed arms industry. There were z. B. in the locomotive factory Comintern developed and produced the tanks T-34 . In October 1941 troops of the German 6th Army captured what was then the fourth largest city in the Soviet Union as part of the First Battle of Kharkov . After the experiences during the Stalin Purges , numerous residents of the city greeted the advancing units of the Wehrmacht with bread and salt.

Shortly afterwards, the terror began against the civilian population. Most of the Jews who remained in the city were killed in the Drobyzkyj Yar massacre . Numerous residents of Kharkiv were deported to Germany as forced laborers. In May 1942, a Soviet attempt at liberation failed ( Second Battle of Kharkov ). In February 1943 the Wehrmacht withdrew to avoid being encircled. In March 1943, after heavy fighting ( Third Battle of Kharkov ) , the city fell back to the Germans. Large parts of the city were destroyed by the fighting. After the Battle of Kursk , the city was finally captured by the Red Army on August 23, 1943 . A total of 270,000 people fell victim to the German occupation in Kharkiv Oblast.

In Kharkiv there were two POW camps 149 and 415 for German POWs from World War II.

After the war, the reconstruction of Kharkiv began. Large parts of the city were redesigned in the style of socialist classicism . Kharkiv grew rapidly in the post-war period. The airport was opened in 1954. In the 1960s, the city became a metropolis. In 1975 a metro network was opened in the city.

Kharkiv has been part of independent Ukraine since 1991. Especially in the first years after independence, the city's economy collapsed, as in most other regions of the former Soviet Union. However, this trend has been reversed since the late 1990s.

In February 1998, the then German President Roman Herzog inaugurated a German military cemetery during a state visit. The war cemetery, conceived as a collective cemetery for those killed in action in the eastern part of Ukraine, is located on the outskirts of Kharkiv within the new 17th civil cemetery.

In 2010, Kharkiv was the first city in Ukraine to be awarded the European Prize of the Council of Europe for its outstanding efforts to promote European integration. During the European Football Championship 2012 in Poland and the Ukraine, a total of three preliminary round matches took place in the city.

Tobacco fair

The tobacco goods fair , founded around the middle of the 17th century in Kharkov or Kharkiv, was a main staging area for the southern Russian and Siberian raw hides destined for fur processing , as well as a sales point for finished fur products . Twice a year the fur traders who had come from Russia and Central Europe were offered the supplies they had accumulated up to then. Although the corresponding trade fairs in Nizhny Novgorod , Kiachta and Irbit were much more extensive in importance and scope, the annual turnover is said to have reached the considerable amount of around 100 million rubles.

The wealthier traders displayed their wares in large fur magazines, while the many sellers of wolf, sheepskin and hare skins of all kinds were content with smaller and simpler stalls. However, all providers took great care in equipping their sales outlets. Often there were stuffed bears or lions at the entrance to the camp, and the rooms and magazines were richly decorated with furs. A visitor from the 1770s described his impressions: “With regular alternation of colors, the walls are covered with a multitude of bears and cats ; Trimmings of fox skins , one as neatly and impeccably as the other, enclose the surfaces, and marten and sable tails form the garlands, festoons , and tassels. In the midst of these rooms, the goods are also laid out in the most beautiful order and selection on shelves and shelves. ”Selected beautiful skins achieved amazing prices. A trader showed this visitor to the fair, who was impressed at the time, a small box containing black fox skins, each with a value of 2,000 to 3,000 rubles.

The largest warehouse in Kharkov was maintained by the merchant Sulichow, commandant of the Russian-American fur trade company . Almost a fifth of the skins from Siberia worth several million rubles were traded on by him. Merchants from Irkutsk exhibited sable hides , skins , foxes and hare skins in large quantities . The fine sables were combined in pairs to form a package and fetched an average of 150 to 200 rubles. The main items were black foxes , blue foxes and silver foxes , martens and otters , especially red foxes of various origins, feuds and hares. There were also black bear and polar bear skins in large numbers . About 40,000 to 50,000 foxes were offered in Kharkov each year, 100,000 to 150,000 hares and several million feuds. Siberian black dog skins were in great demand, each for 50 to 60 rubles.

However, the valuable types of noble fur did not constitute the range that is characteristic of Kharkov. The cheap fur skins, white rabbits, wolves, foxes and sheepskins offered by small traders were typical here . Most of these were already prepared for further processing and, neatly folded, were offered on racks. The buyers were peasants and petty bourgeoisie who bought the skins in barter . The white hare skins were often used as the fur lining of jackets, skirts and even changing cushions .

Pro-Russian protests during the 2014 Crimean crisis

After President Viktor Yanukovych was overthrown on February 22, 2014, clashes between pro-Russian demonstrators and supporters of the Euromaidan have raged in Kharkiv since early March 2014 . The Russian flag was temporarily hoisted on the building of the regional administration. The Russian Foreign Ministry complained that masked people shot at pro-Russian demonstrators during a demonstration in the city on March 8, 2014, injuring them. On March 10, 2014, the presidential candidate Vitali Klitschko was pelted with eggs during a speech in Kharkiv. On the same day, the former administrative chief of Kharkiv Oblast, Mychajlo Dobkin , was taken into custody in Kiev. Dobkin were accused of secessionist aspirations. On the evening of March 14, two people were killed and six injured in a shooting between pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian groups. The Ukrainian Ministry of Interior said members of the Pravyj Sector organization were involved in the shooting and that more than 30 people were arrested. On April 28, Kharkiv Mayor Hennadij Kernes was shot and critically injured. In 2015, Kernes, mayor since 2010, was confirmed in office.

Kharkiv is one of the cities to which the OSCE sent observers on March 21, 2014. On February 22, 2015, three demonstrators during a memorial march for Ukrainian soldiers were killed in a bomb attack.

Attractions

One of the oldest monuments in Kharkiv is the stone cathedral of the Maria-Schutz Monastery from 1689. Here, the customs of Russian sacred buildings are mixed with a composition that is typical of the Ukrainian three-domed wooden churches.

There are other buildings from the end of the 18th century, such as the Maria-Dormition Church , built in 1771, and the former Katherinenpalast, which today functions as a university.

The Choral Synagogue , built between 1909 and 1913, is the largest synagogue in Ukraine.

The magnificent neoclassical theater is the work of the famous Russian architect Konstantin Thon .

The Freedom Square , which is over eleven hectares in size and was built between 1920 and 1930, is characteristic of the city center of Kharkiv . The “ Derschprom ” (House of State Industry) and the university are prominent buildings on this square .

The many theaters and numerous museums in the city provide an insight into the Ukrainian performing and visual arts . The Historical Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts deserve special mention .

The center of the city is around the metro station “Radjanska” (or in Russian “Sowjetskaya”). There still preserved art nouveau buildings mix with architecture of socialist classicism .

Population and language

The city's population consists mostly of Ukrainians and Russians. There are also smaller minorities, such as Armenians , Azerbaijanis , Belarusians , Uzbeks and Tatars .

Kharkiv belongs to the predominantly Russian-speaking part of Ukraine . According to official statistics, around 66% of city residents spoke only Russian at home in 2001, plus many bilingual households. Unofficial statistics put an even higher proportion of Russian speakers. The use of Ukrainian has increased since independence . According to a survey by the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences in 2011, the proportion of the population with Ukrainian as their mother tongue was 28 percent. In contrast, the American International Republican Institute found in 2015 that 95% of the population in Kharkiv only or mainly speak Russian in everyday life, 85% even exclusively. According to this, only 4% of the population only speak Ukrainian.

In 2012 , Russian was recognized as the regional official language in the entire Kharkiv Oblast , and thus also in the city itself. After more than 20 years, Russian now has an official position in Kharkiv again. Traditionally close ties to the Russian neighborhood and the naturalness with which the residents of Belgorod went to the cinema or the market to study in the Ukraine, or even the idea of a "Euroregion Sloboshanshchina" were already through an increasingly visible border before the Euromaidan has been reduced.

The formerly large Jewish community in the city has shrunk massively as a result of the Holocaust and emigration since the 1980s.

Demographic development

Sources: 1810-1913; from 1913

City structure

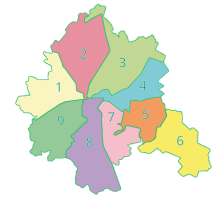

Kharkiv is divided into the following nine city rajons :

| Rajon | Ukrainian name | Russian name |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Cholodna Hora district | Холодногірський район | Холодногорский район |

| 2. Shevchenko Raion | Шевченківський район | Шевченковский район |

| 3. Kiev Raion | Київський район | Киевский район |

| 4. Moscow Raion | Московський район | Московский район |

| 5. Nemyshlia Raion | Немишлянський район | Немышлянский район |

| 6. Industrial Rajon | Індустріальний район | Индустриальный район |

| 7. Sloboda district | Слобідський район | Слободской район |

| 8. Chervonozavodskyi Raion | Червонозаводський район | Червонозаводский район |

| 9. Nowa Bawarija district | Новобаварський район | Новобаварский район |

On 5 March 2013, the urban-type settlement was Kulynytschi and belonging to the same village council community places Braschnyky ( Бражники ) Sajiky ( Заїки ) Zatyshshia ( Затишшя ) and Peremoha ( Перемога ) and the District Municipality Ponomarenky belonging places Horbani ( Горбані ) Pawlenky ( Павленки ) and Fedirzi ( Федірці ) and since then have been part of the city district of Nemyschlja .

Sports

The most important football club in the city is the Ukrainian first division metalist Kharkiv , who was represented in the top division for a long time during the Soviet Union . Its stadium was one of the venues for the 2012 European Football Championship and holds 38,633 spectators. In 2009 it was extensively renovated and expanded; the cost of the conversion amounted to around 50 million euros.

Founded in 2005, local rivals FK Kharkiv also spent some seasons in the highest Ukrainian league, but were dissolved again in 2010.

There is also the football club FK Helios Charkiw , which has been in existence since 2002 and is currently a Ukrainian second division.

The formerly well-known ice hockey club Dinamo Kharkiv played in the Soviet league for a long time, but now mainly focuses on youth development. In volleyball, Lokomotiv Kharkiv should be highlighted.

traffic

The city is the starting point for numerous national and international rail connections (until autumn 2011 there was a through car to Berlin once a week) and has two marshalling yards (Kharkiv-Sort. And Osnowa). The following railway lines, operated by the Piwdenna Salisnyzja , lead to Kharkiv:

- Borschtschi – Kharkiv railway line

- Kharkiv – Kursk railway line

- Kharkiv – Lgov railway line

- Kharkiv – Horlivka railway line

- Kharkiv – Balashov railway line

- Sevastopol – Kharkiv railway line

- Vorozhba – Kharkiv railway line

The inner-city traffic take the Kharkiv Metro , bus - and trolley bus lines , Marschrutkas and Kharkiv tram . There is also an approximately 1.4 kilometer long funicular between the center and the Pawlowe Pole residential area . The city's metro has a total of 29 stations and three lines.

The city also has an international airport ( ICAO code : UKHH; IATA airport code : HRK). Numerous destinations in Europe and Asia, especially in successor states of the former Soviet Union, are served from Kharkiv Airport .

Town twinning

City partnerships exist with the following cities:

Education and Research

Kharkiv is one of the centers of higher education and research in Eastern Europe. The city has 13 national universities. There are also several professional, technical and private universities. The largest universities and colleges include:

- Kharkiv National Vasyl Karasin University (Kharkiv University, 1804)

- National Technical University "Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute" (Kharkiv University of Technology, 1885)

- Mykola Zhukovsky National Aerospace University (founded in 1930 as "Kharkiv Aviation Institute")

- Kharkiv State Academy of Local Services

Several Nobel Prize and Field Medalists were born or worked in the city, including the mathematician Vladimir Drinfeld , the economist Simon Smith Kuznets , the physicist Lev Landau and the biologist Ilya Metschnikow .

Personalities

Climate table

| Kharkiv | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Average monthly temperatures and rainfall for Kharkiv

Source: wetterkontor.de

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Web links

- city.kharkov.ua - the city's official website (Russian, Ukrainian, English)

- Information about Kharkiv (English)

- Traffic information

- Climate in Kharkiv

Individual evidence

- ↑ Demography of Ukrainian cities on pop-stat.mashke.org

- ↑ Alexander Petzholdt: Journey in western and southern European Russia in 1855 . Hermann Fries, Leipzig 1864, p. 417. Last accessed December 18, 2019.

- ↑ chap. 3.1 The German military administration of Kharkiv.

- ↑ Timothy Snyder : Black Earth. London 2015, p. 183.

- ↑ Section 3.3.3. The Soviet interregnum in March 1943.

- ↑ Erich Maschke (Hrsg.): On the history of the German prisoners of war of the Second World War. Verlag Ernst and Werner Gieseking, Bielefeld 1962–1977.

- ^ Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge eV: War Cemetery Charkow.

- ↑ a b c d Without author's name: Smokers' fair in Kharkov - contribution to the history of tobacco shops . In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 41, October 9, 1936, Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Leipzig, p. 5.

- ↑ Emil Brass : From the realm of fur . 2nd improved edition. Publishing house of the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1925, p. 251 .

- ↑ Spiegel Online from March 1, 2014.

- ↑ Moscow outraged by the arbitrariness of right-wing extremists in eastern Ukraine , RIA Novosti website from March 10, 2014.

- ^ "Tourists from Russia" throw eggs at Klitschko , Die Presse of March 10, 2014.

- ↑ Ex-Governor Of Ukraine's Eastern Kharkiv Region Detained , Radio Free Europe website from March 11, 2014.

- ↑ Ukraine crisis: Two dead in shootout in eastern city of Kharkiv as tensions rise ahead of Crimea referendum , The Independent of March 15, 2014.

- ↑ Ukraine crisis: Two dead in clashes in Kharkov , RIA Novosti website from March 15, 2014.

- ↑ Declaration by the Ukrainian Ministry of the Interior of March 15, 2014.

- ^ Spiegel Online: "Ukraine Crisis: Mayor of Kharkiv Shot Down" (accessed April 28, 2014).

- ^ Crimean crisis: OSCE sends 100 observers to Ukraine , Spiegel Online on March 22, 2014.

- ↑ OSCE sends observer mission to Ukraine , RIA Novosti on March 22, 2014.

- ↑ explosion in Gendenkmarsch , report Salzburg24.at

- ↑ Sevodnja August 20, 2012: Русский язык стал региональным в Харькове.

- ↑ Archive link ( Memento of the original from April 3, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Oleksandr Kramar: Russification Via Bilingualism, in: The Ukrainian Week of April 18, 2012, accessed on October 1, 2014 (English)

- ↑ http://www.iri.org/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/2015-05-19_ukraine_national_municipal_survey_march_2-20_2015.pdf

- ↑ The Defense of Diversity , NZZ, March 22, 2019, page 7

- ↑ А.Г. РАШИН НАСЕЛЕНИЕ РОССИИ ЗА 100 ЛЕТ (1811-1913 гг.) On demoscope.ru ; accessed on November 30, 2019 (Russian)

- ↑ Population figures of Ukrainian cities on pop-stat.mashke.org; accessed on November 30, 2019

- ↑ "New Bavaria"

- ↑ Рішення Харківської обласної ради № 678-VІ від 5 березня 2013 року: Про зміни в адмініської обласної ради сланістраорівно-тер

- ↑ Харьков транспортный. Метро. Общие сведения.