sable

Sable fur has been traded as a treasure for over 1000 years . Just as the development of the American continent was largely due to the desire for beaver fur , which was valued at the time for making hat felts , so Siberia was conquered through the hunt for sable and other fur-bearing animals for clothing purposes. Particularly beautiful sable skins had to be delivered as tribute to the Russian crown by the local residents. For centuries, these crown sables were a popular gift from the tsars to foreign dignitaries. Even today, the sable is the most highly rated fur .

The fur of the sable, Russian sobol , is usually sold as Russian sable or Siberian sable and is also called real sable to distinguish it from the fur of the American sable .

History of the sable skin trade

Sable skins have been considered a very special treasure for over 1000 years. For the third to second century BC to the third century AD it is reported that sable skins were exported as "Scythian martens" from the Scythian Empire across the Black Sea . The conquest of Siberia is due not least to the desire to own these valuable furs.

In the second burial mound ( Kurgan ) of Pazyryk in the Altai from the 4th century BC, there was, among other furs, a sable fur jacket that was given to a Scythian princess in the grave when she had to follow her slain husband to death .

Harald Hårfagre (* approx. 852; † 933), the first king of most of the coast of Norway, had his courtiers bring "Sofalaskind", that is sable skins, to feed the coats. Around 1020, King Olaf of Norway equipped ships that sailed across the Northern Dvina to the land of the Permians for the opening of the fur market. From there they brought back feh , beaver and sable skins. Furs were exported to Greece, Rome and the Orient; in the 11th to 12th centuries they were in great demand in Byzantium . The Arab rulers valued the black silver fox fur even more than the sable. They used sable for hats, fur coats and skirts. Ibn Battuta (* 1304; † 1368 or 1377) reported that in India an ermine fur achieved 1000 dinars, while sables were sold for 400 or less dinars.

As early as the 11th century, Novgorod's merchants obtained fur from the peoples of Western Siberia . They sold considerable quantities to Hanseatic merchants at the end of the 14th century. In general, tobacco products took first place in trade with Russia in the Hanseatic League , with feh, marten, ermine and sable playing a special role. Along with Mainz and Duisburg, Cologne was also known as a fur market; As early as the 10th century, fur traders are mentioned at the local fair. They obtained most of their goods from Italy. The Cologne market was famous for its fine types of fur: sable, dark marten and ermine skins and the furrier goods made from them. The division of labor among the furriers was soon so advanced that the noble types of fur could only be processed by " Buntwerk or Grauwerk people ", names that are derived from the fur of the Siberian squirrel. As early as the 12th century there were sable curlers in Cologne.

At the beginning of the 13th century Rudolf von Ems said of a rich Cologne citizen:

... decorated with sable wool

the coat furries ...

and elsewhere:

with minem guote I would

go over mer gĕn Riuzen (Russia)

ze Liflant and ze Prinzen

dā ich vil manegen sable vant.

The sable appeared in the Leipzig tobacco shop in 1573. The Leipzig wholesaler Cramer von Claußbruch sold 49 rooms sable and 27 rooms marten (1 room = 40 pieces) to a merchant in Braunschweig.

Marco Polo reported about the Mongols : “ The rich among this people dress in gold and silk, with sable, ermine and the furs of other animals. “And elsewhere:“ The outside of the tents is covered with black-white and red-striped lion skins (note: tiger skins are meant) so that neither rain nor wind can penetrate. Inside they are covered with ermine and sable skins, which are more precious than any other fur, for they are valued at two thousand golden Byzantines when they are so large that they give a dress, and when they show no fault not entirely without flaws, to a thousand. ““ The Tartars call this hide the king of furs. The animal, which is called "Rondes" in their language, is roughly the size of a polecat. With these two types of skins, the halls and bedrooms are skillfully and tastefully prepared and covered. "

The best sable hides had to be handed over to the tsar as a yassak , as a tribute, from the peoples who were subjugated in Siberia, who gave them to foreign dignitaries as a “crown sable” as a gift. Around 1594, for example, Tsar Boris Godunow sent 40,360 skins to Emperor Rudolf II von Habsburg to support the preparation for a war with Turkey. These included 120 sable hides that were " so precious that no one could determine their value ". Sultan Etiger showed his loyalty to neighboring Russia by pledging himself to voluntarily send 1,000 sable skins to Moscow every year, along with other types of fur.

The Russian historian Karamsin states that around 200,000 sables were captured in the 16th century. In the middle of the 17th century, 70,000 skins were exported every year via the Obdorsk customs station at the mouth of the Ob . In the beginning it was not uncommon for a hunter to come back from a fishing season with more than 100 sables. On the upper reaches of the Olekma , each hunter caught an average of 280 sables per season.

The Stroganows had been fur traders for generations, the first of the family being Spiridou , who died in 1395. At the end of the 16th century, with the help of the Cossack leader Yermak , they subjugated large parts of Siberia in order to forcibly exploit the abundance of fur there, often at great cruelty to the inhabitants. At the beginning of the negotiations, the Cossack had the Tsar handed over 50 beaver and 20 black fox skins, and above all 2400 sables. The sables previously sent as gifts by Sultan Etiger have now been converted into raised fur tributes for Tsar Ivan IV and the Stroganovs. The Stroganovs financed their later monopoly on the Russian salt trade, for the establishment of which enormous funds were needed, to an excellent extent by trading in sable skins.

The number of pelts required was not the same everywhere; it depended on the abundance of animals and the behavior of the population. It wasn't uncommon for a single hunter to have ten, twenty, or more sable hides to deliver. In areas where overexploitation was already very advanced, the option of replacing the Yassak with money was made early on, beginning in 1626. Under Catherine II (reign 1762–1796) the worst evils were abolished. In the first year of her rule, Katharina lifted the fur trade monopoly of the Tsar's crown. The Jassak no longer had to be raised by individuals, but by a family, the tribe or the entire camp. But it was only the Empress Elisabeth (reign 1741–1762) who made serious efforts to protect the mostly brutally exploited indigenous population after repeated uprisings. Now the unrest subsided, although assault, looting and fraud continued to occur.

Trade seems to have been lucrative for European merchants too, despite the high losses that they often suffered on the way to their countries. For example, a Dutch merchant in Russia bought sable skins for six rubles, which he was able to sell again in Amsterdam for the equivalent of 50 rubles. Because of the large quantities, the sable fur was not so popular at that time. The Russian historian Karamzin writes that up to two million skins were sold annually in the 16th century. The East Siberian Kamchadals exchanged six skins for a knife. An ax cost as much hide as could be pressed into the hole provided for the handle. For a long time it was the established commercial custom that the buyer of a copper kettle filled the kettle with sable fur as the purchase price. From the beginning of the 20th century it is reported:

“The thought of the sable and the sable hunt dominates the whole life of the Kamchadal. His baptism is paid for with sable skins, if he goes to school, he has to deliver a sable skin for class every year, if he is married, it costs another sable skin and if he closes his eyes for the last sleep, his relatives have to Denial of burial again with sable skins. [..] Even when trading with his own kind, the Kamschadale knows no other money than sable fur; If a sable fur is considered too valuable for the object to be traded, then some inferior fur is simply 'given out', but no Kamschadalen would even think of any other means of payment than sable fur as the basis of a trade. "

Because of its price, sable was a fur that was often worn, especially by the nobility. Blankets were made out of them, and even the dead were buried with sable fur hats. The skins that were not delivered to the crown, but given in free sale to Russian traders buying for export, were called "Grenzzobel".

A major trading partner for Russia over the centuries has been China; the deliveries were made via the border town of Kiachta . A special feature was the assessment of sable skins by the Chinese. While the dark sable had a higher value in Russia as early as the 15th century, the Chinese fur traders paid more attention to other properties of the fur, such as size, smoke and hair density. They were good buyers for good quality light-colored gold sables from Western Siberia, but only at half the price for dark sables. The darkest and therefore most expensive skins therefore did not go to Kiachta, but to Moscow and Petersburg and from there to Turkey and Europe. It should be noted that the areas of origin of the dark sable in Dauria and on the Amur are closer to China.

Several 100,000 sable skins were offered every year at the large fur fairs in Irbit. As a result of the relentless hunt, these quantities decreased more and more, from 1910 to 1913 there were only 20,000 to 25,000 furs. This ultimately worried the trade to such an extent that the Irbit tobacco merchants made a petition to the government to protect the sables from ultimate extinction. The imperial Russian government therefore banned sable hunting from February 1, 1912 to October 1, 1916 At the beginning of the 1920s, the Soviet government decreed closed seasons and extensive protective measures, such as sable reserves. For a few decades the sable had practically disappeared from the world market.

It is reported that in Nizhny Novgorod sables were only shown when the sky was clear and not when the weather was cloudy and there was snow.

In October 1927 the Hudson's Bay Company brought 3,272 Siberian sables onto the market, in January the following 1,266 pieces. In April 1928 there were 401 skins, but because of the high price they were not able to buy. In the same year another 200 came from auction house CM Lampson & Co. and from Fred. Huth & Co in London 550 pieces in addition. That was no longer a comparison to previous centuries and only a fraction of what the market would have absorbed. In 1951, for the first time after the war in London, a slightly larger amount of 4,500 sables was offered again.

In 1931 sable was started to be farmed in what was then the Soviet Union, and around 10,000 of the animals were later released. By the mid-1960s the population had recovered to such an extent that any administrative district in Siberia produced 40,000 to 50,000 sable skins again.

In 1934 a Berlin furrier succeeded in getting orders for two sable coats and a sable cape despite the lack of goods and to the incredulous amazement of his colleagues in the branch: “ In weeks of endeavor, the capable business owner managed to get the necessary number of sables from private ownership. He commissioned many finishers to find well-preserved scarves and necklaces. Such pieces have survived in Russian circles, and so the necessary material was collected and could be purchased at a price which, however, cannot be compared with the fantastic demands for fresh goods. “Even before the Second World War , precious men's sable coats that came close to the price of 100,000 marks made a name for themselves, Kaiser Wilhelm II owned one, and Kaiser Franz Joseph is said to have owned two .

In 1963, after visiting a Russian sable farm in Puschkino , the then very popular Frankfurt zoo director Bernhard Grzimek vividly described the situation at the beginning of the 20th century, although his statements about the number of sable coats that existed at the time seem a bit understated and about the fur prices a bit exaggerated. Nevertheless, they are certainly not entirely wrong, with the small number of skins it was very difficult to sort a clean assortment for a coat, as the top price for individual copies, the skin price is at least conceivable.

My dear mother had a sable coat. He was already quite old and a bit gruff, but when she mothballed him over the summer to mend it in the early twenties, the furrier involuntarily spoke a little quieter with respect. These Russian fur animals had already become so rare that they were almost considered to be saga animals. Recently I read somewhere that there were only two sable coats in the world. Stalin gave one of them to Empress Soraya on a state visit; a sable skin should cost eight to twenty-four thousand marks.

His mother's sable coat was made from a large so-called "driving coat", that is, a coachman's or motorist's coat, his grandfather's. The mother had removed the fur lining and had the furrier reprocess it. Grzimek also mentions that although there were more animals in Siberia than there were a hundred years ago, the sable skins had remained a treasure: “Even Adolf Hitler had granted them a maximum price of 1,000 marks in his price regulation. As early as 1912, the Penizek and Rainer company in Vienna, then a leading fur model house in the world, asked for no less than $ 24,000 or 100,000 marks for a sable coat. A raw hide costs between 200 and 1200 marks in retail in West Germany today. ” Furriers had told him that there were again 15 to 20 sable coats in the world. He took the sable as an example of the fact that "wild animals do not have to become extinct if the state takes their fate in hand" .

Even in the Middle Ages, the leftovers from the processing of the hide were not simply waste. In addition to coins, they were used as means of payment in Scandinavia, the so-called kunen , or marten skins . "In addition, parts of pelts (resana cut off immediately), mustache pelts (mordki), paw pelts (lapki), etc. also circulated. The use as a medium of exchange lasted into the 15th century."

Sable fishing, which has been practiced since ancient times, still had a certain importance for Siberia in the middle of the 20th century, although the economic share was incomparably smaller because of the development of other powerful natural treasures.

According to the jury, Fränkel's Rauchwaren Handbuch, around 1988 ninety percent of the pelts were sable and only ten percent were caught in the wild.

The fur

In appearance and way of life, the sable is a real marten. The elongated animal has a fur length of about 35 to 45 cm, the bushy tail is 12 to 15 cm long; The skins of males are larger than females.

The very dense hair is medium-long, finely silky and extremely soft. The soles of the feet are hairy. In winter fur, the guard hairs measure 35 to 59 mm, the woolly hair 18 to 29 mm and the tail hair up to 85 mm. The wool hair of the sable is thicker than that of the mink, but the typical guard hair of the sable is around 10 µm thinner than that of the mink, the guide hair even 15 µm compared to the same type of mink. There are around 13,500 hairs on one cm² of leather.

The color is predominantly dark brown with shades from deep dark to light and brown-yellow, also yellow-gray. The reddish orange to gray throat patch varies in size, sometimes it is only hinted at.

Despite the fine hair, the coat is quite durable. The durability coefficient is 40 to 50 percent. If the fur animals are divided into the hair fineness classes silky, fine, medium-fine, coarse and hard, the sable hair is classified as fine.

In specialist circles, the color is referred to as "water". The more even and darker, almost black, the water, the more noble the fur is according to traditional beliefs. Brockhaus wrote in 1841: “The fluff gives the bellows its enamel by showing through the contour, which the hunters call water.” However, the darkest pelts are found in the smallest varieties. The undercoat is yellowish-gray to blue-gray. Heavily silver awned skins are also called silver sable . Completely white ones are very rare. As Kaltan is called in Russia (China?) The Sommerzobel, their trade is prohibited.

Sorting the skins is very difficult. Different colored sables are not only found in remote areas, but also within small areas, even in small forest islands or opposite river banks. It is not easy to find a few dozen color-matching skins from a batch of several thousand skins.

According to its distribution over the whole of Northern Asia (formerly also in Northern Europe) the sable forms numerous subspecies or color variants. Pawlinin describes this in 1966 as follows. However, he mentions that the division into so many races will probably not be sustainable zoologically.

- 1. Tobolsk sable

- Large, tail relatively long and bushy. Distribution: Pechora Basin, Northern and Middle Urals, Middle and Lower Ob with the exception of the tundra and steppe areas.

- 2. Kuznetsk sable

- Without description, the reality of this breed is doubtful. Distribution: western slopes of the Kuznetsk Alatau, river area of the Tom.

- 3. Altai sable

- Significantly darker than Tobolsk. Dense undercoat, awns relatively short and sparse, hardly cover the undercoat. Distribution: Altai mountain valley.

- 4. Tungus sable

- Smaller than the Tobolsk sable. The color is on average darker than that of Tobolsk. The hair is thick but coarse. Distribution: River basin of the Lower and Stony Tunguska.

- 5. Yenisei sable

- Medium in size, similar to the Tobolsk sable. The color is quite light, dark specimens are rare. The fur is dense but coarse. Distribution: the taiga in the plain between the Angara and the foothills of the Sayans.

- 6. Angara sable

- Significantly smaller than the Yenisei sable. Distribution: River basin of the Angara, north to the watershed of the Stony Tunguska, south to the Karsk steppe. The reality of this breed is dubious.

- 7. Sayan sable

- Medium-sized. The basic color of the color is usually darker than that of the Yenisei sable, mostly dark brown to blackish brown. The hair is quite thick, soft and silky. Distribution: Sayans and Tuva.

- 8. Bargusin sable

- Medium-sized. Very dark and shiny hair, silky and thick. Distribution: Bargusin Mountains, foothills of the Jablonowoj (Apple) Mountains, river basins of the Olekma and the Vitim.

- 9. Ilimpeja sable

- The size is similar to the Tungus sable. However, the color is significantly darker. Distribution: north of the Lower Tunguska, Taiga, in the river areas of the Tura, Kureika, Anabar and on the upper reaches of the Olenek.

- 10. Witim sable

- Similar to the Barguzin, but larger, smaller than the Tobolsk, Altai and Chikoi sable. Dark color, weakly developed throat spot. Distribution: right bank of the Kerenga and Lena, upper reaches of the Witim and the Upper Angara. The actual existence of the breed was unclear at the time.

- 11. Chikoi sable

- Darkest, very large breed. Only the Tobolsk, Altai and Kamchatka sable are larger. Distribution: southeast of the Jablonowoy Mountains, river basin of the Chikoi.

- 12. Yakut sable

- Very small with extremely thick and silky hair. The coloring is very different, but mostly dark. Distribution: Yakutia.

- 13. Sakhalin sable (Far Eastern sable)

- Tiny; very bright, more reddish than the Kamchatka sable. The throat patch stands out only a little. Distribution: area of the lower reaches of the Amur, Ussuri area, Sakhalin, Shantar Islands.

- 14. Kamchatka sable

- The largest breed. Very different colors, mostly not very dark brown. with a yellowish-gray undercoat. The throat patch varies in size and color. Very thick hair but a little coarse. Distribution: Kamchatka.

- 15. Japanese sable

- Resembles the sables of the latter origins, but has a short tail. The fur quality is lower than that of the Siberian sable. Distribution: Japan and the Kuril Islands.

The kidus from central and western Siberia were often viewed as a bastard of sable and pine marten. According to F. Schmidt, his own unsuccessful attempts at pairing on a Russian experimental farm as well as more precise observations and comparisons of fur have always shown that this is pine marten fur. Before 1966, however, it began to be sold at auctions as the provenance of the sable. The Urals were specified as the region of origin, and the quality was sorted into 3 types. In 1987 the Russian auction company offered 1000 kidus skins. The American sable, zoologically spruce marten, was originally called kidus in Russia.

Wholesale today

Until the second half of the 19th century, like ermine skins , sables were traded by rooms. A room smoked were 40 skins, 4 roofs were 1 room. Today the skins are bundled in 2, 4, 6, 8 etc. pieces.

It is delivered in a wide bag shape with the hair facing outwards. Yakut sable hunters were distinguished by the fact that they pulled the pelts with their hair outwards, without damaging the eyes, ears or snouts, and left the paws without bones with all claws and cored tail in the hide. The saying "pull someone's fur over their ears" refers to this form of skin-protecting skin.

In 1930 it is mentioned that most better sable hides are made wider and shorter than they are naturally. This is done using a special drying process; generally they are 10 inches (25 cm) long .

I. Russia

The Russian tobacco trade differentiates as a standard

nach Herkommen (Provenienzen): 1. Bargusinsky 5. Pribajkalskyy 9. Nikolajew 13. Altaisky 17. Tobolsky 2. Kamtschatsky 6. Jakutsky 10. Amursky 14. Mongolen 18. Tuvinsky 3. Witimsky 7. Karamsky 11. Sachalinsky 15. Sejsky 4. Jenniseisky 8. Irkutsky 12. Minusinsky 16. Kustretzky nach Sorten: I. Sorte vollhaarig II. Sorte weniger vollhaarig III. Sorte halbhaarig Die Zobel der I. und II. Sorte werden unterteilt in a) Tops, b) Half Tops, C) Collar Sables (Kragenzobel), d) Lining sables (Futterzobel) nach Farben: 1 bis 7, das heißt vom dunkelsten bis zum hellsten Braun, die hellsten sind sogenannte Farbware.

In the past, sables were sorted into grades I and II: heads, half-heads, collar sables and fur sables.

Depending on their origin, the skins are more or less dark and different in hair texture. The hair is usually thick and stocky.

The darkest, almost blackish-brownish with silvery awns and thin leather, come from Barguzin, Vitim and Eastern Siberia, and partly from Yakutsk and Okhotsk.

Lighter varieties come from the districts on the Yenisei and the Lena, while some darker varieties also come from the areas on the Amur.

In the border areas in the north between the forest and the tundra, there are particularly large pelts, but they are lighter and have less fine hair.

The Russian tobacco industry summarizes the various origins in four categories, regardless of the respective quality:

- Golowka - particularly dark (deep black or black-brown), black awn with a slight brown cast, undercoat dark blue-gray without light awn tips, weakly pronounced throat spot, sometimes as an orange “star”.

- Podgolowka - lighter, center back and flanks dark brown without a fox-red shade. Awn dark brown, undercoat blue-gray with chestnut-colored hair tips; Head slightly graying; indistinct throat patch.

- Vorotovy - medium dark; the top is dark cinnamon brown with an eel line on the back; slightly fox-colored flanks. Greyish under hair with fox-red hair tips; slightly graying head with indistinct throat spot.

- Mechowoj - light (light cinnamon brown, sand yellow or straw yellow); Awn cinnamon brown, light gray undercoat with fox-red or pale yellow hair ends; blurred throat patch; big.

During the time of Soviet rule, the entire tobacco trade was handled by the Russian trading company Sojuzpushnina . The company was fully privatized on November 13, 2003, and the Russian fur fur auctions are still held here today (2011). In addition, there is now a free tobacco market.

II. China

The skins from China, especially those from the former Manchuria , are shorter-haired and thinner. Most of the delivery came from Ho-Lung-Hiang. The quality corresponds roughly to that of the Amur slab. Another variety came from San-Tsing (Sansin sable). They are flatter in the hair, the color is partly dark, bluish silver. In contrast to the Russian sable, the raw hides were usually elongated, with the leather side facing out, on the market. However, no more deliveries have been reported for years (1988). A large part of the furs was used in China anyway, for the maquas or riding jackets for mandarins and for trimmings.

III. Japan

The pelts coming from Hokkaidō (Yesso) and the Kuril Islands have the normal size, they are quite silky, light, reddish-yellow in the back. The throat is more fiery red. With the increase in the population, the catches fell, as early as 1966 the sable was no longer of economic importance there, at least on Hokkaidō hunting was prohibited. The skins were not delivered round, but cut open.

Breeding

The cultivation of sable for fur purposes began in 1931 in Pushkino , not far from Moscow. The head of the farm was the German zoologist Dr Fritz Schmidt, who used to be the head of breeding at the oldest Central European fur farm in Hirschegg (Kleinwalsertal) in Vorarlberg. In the following year the first breeding success was recorded with 30 young animals, in 1934 there were 124 puppies. Over the years, almost pure black sables with silky, shiny hair were bred, which by 1988 were rated higher than the best furs of wild sables. Around this time 90 percent of the pelts came from farm breeding, ten percent were caught in the wild, and 100,000 pelts were exported.

processing

In China, an industry for the production of semi-finished fur products arose much earlier than in Europe , which facilitated trade and the final production, especially with small pelts and the remaining fur. The skins or skin parts were mainly put together to form so-called crosses. Chinese garments such as the robes of the mandarins could be made from the crosses with little effort. At the end of 1900 a furrier from Edinburgh reported on the import of a small batch of fine Chinese sable skins, which were mostly composed in the shape of a cross. They were usually artificially darkened, either blinded, that is, the ends of the hair had been re-colored, or they had been illegally tinted darker in the smoke, with the hair suffering.

The Siberian hunters were also said to be very clever at dyeing sable skins with lead shot, which they put into the fur and then shake so that the fur becomes evenly dark . Others hung them in the smoke, but most were so clumsy that a professional could easily spot the fraud.

In Germany, too, companies were busy re-dyeing sable hides. However, in Leipzig and other places, those fur refiners were called sable dyers who dyed other types of fur, especially martens, in sable color. The Nuremberg master furrier Stephan Neudörfer is reported to have lived around 1500 that he knew how to trim a sable fur so finely that the buyer could pull it through a heraldic ring .

A specialist furrier book from 1895 describes how to use leather wedge galons to enlarge trapezoidal tails and bring them into a rectangular shape for further processing. Around this time, in addition to fur linings, the furriers mostly made small parts such as sleeves and collars. On the other hand, making a pelerine out of tails is significantly more difficult, indeed a work of patience . Sable throats, which are processed into food in connection with the claws, on the other hand , have a very fine effect , are very sought after and are also paid for accordingly. However, the main places of fur residue recycling outside of China are still today, from origins in the 14th to 15th centuries, the Greek Kastoria and the nearby smaller town of Siatista .

In 1965, the fur consumption for a fur board with 60 to 80 pelts sufficient for a sable coat was specified (so-called coat “body”). A board with a length of 112 centimeters and an average width of 150 centimeters and an additional sleeve section was used as the basis. This corresponds roughly to the fur material for a slightly exhibited coat of clothing size 46 from 2014. The maximum and minimum fur numbers can result from the different sizes of the sexes of the animals, the age groups and their origin. Depending on the type of fur, the three factors have different effects.

When processing into garments, the pelts can either be processed in their natural, rectangular shape after cutting and straightening, or they can be left out. The decision of the fur designer for one of the two options depends on the one hand on the quality of the skins available to him and on the prevailing fashion perception.

There is probably no type of fur in which, despite superficial similarity, the furs are as different as in the sable. Even with skins of the same origin it is sometimes hardly possible for the furrier to find two almost identical skins. When leaving out, skins are cut in V- or A-shaped cuts and, at the expense of the width, sewn together in such a way that one skin results in the new stole, jacket or coat length. The outlet cuts can only be moved relative to one another to a certain extent without any loss of quality, and the number of cuts that are around four millimeters wide at Zobel is limited by the length of the skin. Above a certain required length, the area for a strip must be enlarged to a single skin part by so-called cutting into several, usually two skins, before it is released. In order to achieve a good result, the greatest possible agreement within an assortment is required. Even then the work is very difficult and requires a lot of brushing experience. Omission is always preferred when fur fashion demands narrow, flowing optics for other types of fur. This was the case for at least a few decades after the Second World War , when exuberant mink coats dominated fur fashion not only in the main consumer country, Germany. If you put the skins next to each other and in rows, sorting is a little easier. At present (2011) full-skin processing is preferred.

The fashion

Auguste de Beauharnais , Duke of Leuchtenberg (around 1835)

István Tisza , Prime Minister of Hungary (1861–1918) with a sable-trimmed dolman

- Boris Michailowitsch Kustodijew , self-portrait with sable collar andhat (1912)

In 2006 Russian and German archaeologists found the ice mummy of a Scythian warrior from the Pacific culture (5th – 3rd century BC) during excavations in the Altaj (Mongolia ). “The 'blond prince' from the mountains was kept warm by a magnificent fur coat in which sable was used. The skins were colored blue and red with Indian indigo and probably Kermes imported from Persia ” .

Although it is said of Emperor Charlemagne that he loved simplicity, according to Einhard he wore a fur made entirely of otter and sable (murinae pelles) and a Hermelin-trimmed Gallic coat. Even Napoleon Bonaparte had such a piece as a sign of French rule later. Angilbert , the emperor's chaplain, writes about Charlemagne's daughter Bertha : " ... and the snowy neck proudly bears the delicious marten ", about her sister Theodrada : " ... the coat seems trimmed with dark smoke from afar, " the sable. In general, the secular as well as the ecclesiastical princes revel in the finest and most noble furs towards the 10th century, Russian crown sables are mentioned in this context. A kind of overdress emerged in which the fur side was worn outwards. The motive of wanting to stand out from the rest of the population remained important for certain types of fur until the late Middle Ages and beyond. This was not only true of secular dignitaries; the lower and higher clergy also belonged to the main buyers. The chroniclers report of the finest fur for bishops and other church princes; Sable, martens, ermine, otter and beaver skins were just good enough for them.

In the first half of the 16th century, the fashion costume no longer had a decidedly aristocratic character as it had before in the heyday of Burgundian fashion. It is carried in the same way by the spiritual leadership and by citizens who have achieved power and prestige. The difference is only apparent when Albrecht Dürer painted the Nuremberg councilor Hieronymus in a scarf with a wide marten collar (1526) and the emperor Maximilian I in sable fur (1519), the wealthy merchants could also afford sable.

The Italian fashion, which differs in cut, was also adorned with ermine and sable if it wanted to achieve a rich effect. When Lucretia Borgia married Count Alfonso D'Este of Ferrara in 1502 , she wore a white dress embroidered with gold with a dark, sable-trimmed velvet cover to receive the Ferrarese ambassadors.

The consumption of fur increased from century to century. Numerous dress codes tried to restrict this. For the entire citizenry, clothing and costume were regulated in detail. Regulations said what types of fur were allowed at the respective stands, how the processing had to be made and other things. Under Edward IV of England, only the nobility were allowed to wear sable clothes. With a few exceptions, however, these measures were unsuccessful. The Saxon State Police Ordinance of 1661, for example, decreed who was allowed to wear “good sable hats” and who were only allowed to wear colored or even just ordinary “marten hats”: “ So even the uncolored, good sable hats and mugs should only be our councilors, noble court Officers and aristocrats, their wives and daughters, good sable hats and colored sable hats to whom professors, doctors, experienced practitioners, secretaries and their wives and daughters "left off", but who by the way were completely forbidden and referred to martens or the like be. Everything at penalty thirty thalers, whoever acts again. "

Rebbe Naftoli Tzvi Labin from Ziditschov with Schtreimel

Feodor III. (1661–1682) with sable-trimmed tsar's crown

The sable was the most valuable type of fur of the Middle Ages, followed by the ermine; often both were impressively combined in one item of clothing. The Marquis de Stainville had a gala dress made for himself, the trimmings and lining of marten and sable fur cost 25,000 livres. Due to the increasing consumption, the prices for a sable fur rose to 170 rubles in the following centuries, a whole sable fur is said to have occasionally cost 20,000 rubles. If you were sufficiently wealthy, you wanted to show that regularly. The coat or the scabbard was completely lined with fur and the fur trim was particularly lush, the fabric cover was made of valuable silk or wool. Sable fur was often only used for collars or trimmings, but cheaper types of fur came inside: " ... they had mostly lined their marten screws and sables on their backs with sheepskins, " says the Zimmerische Chronik .

In poetry and truth, Goethe gives an indication that the sable was still present in the middle of the 19th century, meanwhile also as a trimming on middle-class clothing. He tells how his mother visits him on the ice rink and he, scantily clad and freezing, asks for her fur: “She sat in the car in her red velvet fur, which, tied together on her chest with strong golden cords and tassels, looked very stately. Give me, dear mother, your fur! ... At the moment I was wearing the fur, which was purple in color, reaching down to the calves, trimmed with sable, adorned with gold, and the brown fur hat I was wearing was not bad at all. "

The fur actually played a subordinate role in the changing fashions, until the 19th century it was mostly just a warming and decorative feature, there was no fur clothing that helped determine fashion. Individual parts occasionally made an exception.

Zibellini , the so-called flea fur of the Middle Ages, have their name, borrowed from the Italian, from Zibellino, the sable. The animal-shaped scarves, now known as fur necklaces, were probably not until later generations that the wearer could use them to attract her fleas and then shake them out. The parasites are attracted by body heat, not by the soft sable hair. Often the head and paws were covered with the finest goldsmith work and precious stones, which explains that mostly only princesses could afford this decorative fur. The rich Augsburg patrician Philippine Welser owned a flea fur made of sable with a golden head and paws set with rubies and emeralds. The eyes were grenades, and there was a pearl in the snout. Around 1900 until some time after the Second World War, fox necklaces, necklaces made from mink or other types of marten, and those who could afford them, made from two, four or more sable skins, were very popular accessories.

Maria Ludovica of Spain with an ermine and sable (1763)

Catherine the Great (1729–1796)

Pola Negri , silent film actress, in a sable coat (1927)

Shirley Temple , actress (1944)

The headgear also often had a more or less wide border made of valuable types of fur. At first they were only used for the hats (13th century), later also for the hats, and occasionally the whole part was made of fur. As mentioned, in the 17th century the sable hat was already permitted to notables, such as nobles, court officers, councilors and their wives and daughters, as well as the slightly lower-ranking professors and doctors. Up until the 17th century, the "knäsen", the crowns of the tsars, were sable hats adorned with gold and precious stones (see Monomach's hat ). A military headgear in the shape of a hussar cap is the busby made of sable fur. In Great Britain it is only worn by the Royal Guard and the Royal Horse Artillery . Prior to 1939, "The Busby" was also used by Hussar Regiments, the Royal Artillery, the Royal Pioneers and the Royal Intelligence Units.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the muff appeared as a warming hand flatterer, usually made of fur. Initially only worn by women, by the end of 1700 it was naturally part of the cavalier's wardrobe , from which it disappeared again in the early 19th century. A sable muff may complement the sable collar and perhaps also cuffs on the fashionable costume of the time. Initially a small roll, the muff has now reached an opulent size, then becomes smaller again, until then in the first quarter of the 20th century large muffs are modern again, often garnished with paws, tails and heads.

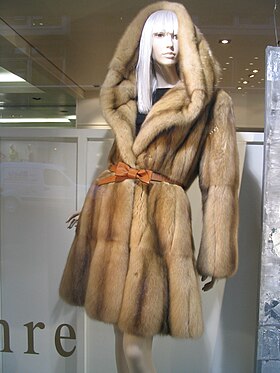

The decisive change occurs at the turn of the 20th century. Jackets, coats and capes made of fur are added to hats, caps, collars and muffs. Sixty years later, fur clothing helped determine fashion, but sable coats and jackets increasingly remain very exquisite, rare pieces that provide information about the social and economic success of the wearer, mostly a wearer, due to the ever decreasing availability of the skins.

Pola Negri , film star of the silent film era, wears a lush, long, cross-processed, exuberant sable coat in a photo from 1927. Her colleague Shirley Temple , who was born the following year and was a former child star, was welcomed in in 1944 with a very exquisite sable, also made with an outlet technique. The German singer of Russian songs Ivan Rebroff was known for his lush furs. Most recently he wore a sable ushanka at his concerts . Jay-Z, the rapper born in Brooklyn in 1969, also shows his social rise with a - lush - ear flap cap made of sable fur.

Sables are still used today to make all kinds of clothing, coats and jackets or smaller items such as fur stoles , capes, trimmings and fur hats . The remnants of fur that fall off are put together to form panels, which are mainly used for inner lining and trimmings. Sable tails, probably preferred those of the so-called American sable not dealt with here, are also used for the Schtreimel , the Hasidic Jews' almost wagon-wheel-sized cap.

Olivia Sage , American philanthropist (1828–1918) with a sable mustache

Esther Pohl Lovejoy (1869–1967), doctor and suffragette , with sable necklace

Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll , with sable cap and collar (around 1880)

Yvonne de Gaulle, wife of the President of France with a sable cape at a banquet for the inauguration of the German Embassy in Paris (1968)

Jean-Etienne Liotard , self-portrait (1744)

Ivan Rebroff , singer (2006)

The American rapper Jay-Z (2009)

Numbers and facts

- 1729 to before 1988

| 1729 | 1864 | 1910 | 1923/24 | 1925 | 1947 | 1949 | 1951 | 1955 | 1956 | before 1988 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12,480 | 245,000 | 220,000 | 6,000 | 19,500 | 36,600 | 31,100 | 40,400 | 67,500 | 68,500 | 100,000 |

- Quote: In the second half of the 17th century 579 rooms (29,160 pieces) and 18,742 sable tails were made in one year; from Narva two rooms (80 pieces), while trade with China was little at this time.

- In 1912, a contest between two millionaire women from New York who was related by marriage to find out who would have the most expensive fur was reported. After one of them had bought a sable worth 80,000 marks, her sister-in-law gave her the order on the same day to get her the “most beautiful” sable fur in the world: “A specialist was sent to Europe and returned in May with over 100 Russian sable furs back, which initially cost 147,000 Mk. The most skilled fur workers went to work and now at last Ms. Ada Drouillard was able to appear in public rehabilitated, wrapped in a fur that weighs only 7 pounds, consists of beautiful deep brown fur with white hair tips and cost a fortune. The beaten rival today only laments not the loss of her fame, but also of her fur; It would have been an unfortunate fate that her 80,000 Mk. expensive competitor fur was mysteriously stolen from the opera on the very same day, while Mrs. Ada Domuillard celebrated triumph with her new fur ”.

- In 1978 the Abendpost published in Frankfurt am Main reported that an American lady of "ripe old age" (a Texan from a multicompany, "hostess of exclusive receptions in Washington") had acquired a floor-length sable coat worth $ 130,000. With that she had ousted actress Elizabeth Taylor from the Guinness Book of Records , who owned a coat worth $ 125,000.

- Before 1944 the maximum price for sable skins was RM 1,000.

- September 2007 . Even today the sable is one of the most valuable types of fur. At the auction of the Russian fur trading company Sojuzpushnina in St. Petersburg in September 2007, an average price of US $ 188.69 for raw farm sables and US $ 2600 per fur for the top bundle was achieved.

- In December 2010 , 9907 farm sable skins were offered at the 183rd Sojuzpushnina auction, 99 percent of which were sold at an average price of US $ 169.89. 95 percent of the 10,902 wild sable pelts sold at an average price of US $ 96.05. The prices were 15 percent below the level of the auction in April of the same year. The main buyers were from the US, Russia, Japan, Italy, Greece and China. The top lot was bought by a furrier from the Greek fur sewing town of Kastoria for a Russian company.

- In January 2012 , at the 190th Sojuzpushnina International Fur Auction in St. Petersburg, the 350,441 raw wild sable hides on offer were completely sold at an average price of US $ 262.39. The top lot with Bargusinsky skins was auctioned by a Moscow company for US $ 5900 per skin.

- In April 2013 , the 368,688 raw wild sable hides were sold at the 191st Sojuzpushnina International Fur Auction in St. Petersburg at an average price of US $ 211.13. Bargusinsky fetched an average of US $ 217.02 (maximum price US $ 3300.00), Kamtschatsky US $ 249.91 (maximum price US $ 450.00), Jakutsky US $ 123.16 (maximum price US $ 220.00), Eniseisky US $ 114.75 (maximum price US $ 145.00), Amursky US $ 120.50 (maximum price US $ 200.00). A Greek dealer from Kastoria bought the top lot for a Moscow customer.

See also

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Paul Schöps, in connection with H. Fochtmann, Richard Glöck, Kurt Häse, Richard König , Fritz Schmidt (Überlingen): Der Zobel . In the fur trade. Volume X / New Series, Hermelin-Verlag, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig / Vienna 1959, No. 4, pp. 154–161.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Vladimir Pawlinin, Sverdlovsk: The sable . A. Ziemsen Verlag, Wittenberg 1966.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The oldest surviving boot made of leopard skin . In: Das Pelzgewerbe 1966 No. 4, Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin et al., P. 173.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan: On the history of the tobacco trade in antiquity and the Middle Ages and the development of the Russian-Asian region from 16.-18. Century. Inaugural dissertation. University of Cologne 1940, p. 23. Table of contents . Primary source Joh. E. Fischer: Siberian history from the discovery of Siberia to the conquest of this country by Russian weapons . St. Petersburg 1768, II volumes, p. 3119.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 26. Primary source Chwolson: Reports on the Khazars, Bolgars, Magyars, Slavs and Russians by Abu-Ali-Ahmed-Ben-Omar Ibn Dasta, 1869, p. 163f; at J. Kulischer: General economic history of the Middle Ages and modern times . Munich / Berlin 1928/1929, Vol. I, p. 11.

- ↑ Bruno Schier : Ways and forms of the oldest fur trade in Europe . Archive for fur studies Volume 1, Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Frankfurt am Main 1951, p. 22. Table of contents . Primary source: Ibn Jûsuf Nizâmï, Iskanrnâmeh, edition of the Chamse, Bombay 1887, p. 400.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 38. Primary source H. Bächthold: The north German trade in the 12th century , Berlin and Leipzig, 1910, p. 77.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), pp. 38–39. Primary source H. Loesch: The Cologne guild documents up to 1500 . Bonn 1907, vol. I, p. 307 ff.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 42. Primary source Fritz Rörig: Hansic contributions to German economic history . Breslau 1928, p. 220.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 40. Primary source R. v. Ems: The good Gerhard , Hersgr. M. Haupt, p. 780 ff.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 40. Primary source R. v. Ems (see there), p. 1194 ff, cf. Bächthold (see there); P. 285.

- ↑ Erich Rosenbaum: The masterpiece order of the Leipzig furriers . In: Das Pelzgewerbe , Volume VII / New Series, 1957 No. 4, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Leipzig et al., Pp. 158-162.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 32. Primary source Lemke (see there), but here: The journeys of the Venetian Marco Polo in the 13th century . Hamburg 1908.

- ↑ a b c d Christian Franke / Johanna Kroll: Jury Fränkel's Rauchwaren-Handbuch 1988/89 . 10. revised and supplemented new edition, Rifra-Verlag Murrhardt, pp. 49–53.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 69. Primary source J. Semjanow: Die Eroberung Sibiriens . Berlin 1973, pp. 50-51.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 83. Primary source Fischer (see there), pp. 211–213.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), pp. 70, 76. Primary source Semjonow (see there), p. 44.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 82. Primary source Gustav Krahmer: Russia in Asia . Leipzig 1900–1902, VI volumes, p. 212.

- ^ Marie Louise Steinbauer , Rudolf Kinzel: Fur. Steinbock Verlag, Hannover 1973, p. 41.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 73. Primary source Semjonow (see there), p. 44.

- ↑ Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 153/54, Leipzig, December 24, 1929, p. 3.

- ↑ a b P. Larisch: The furriers and their characters . Self-published, Berlin 1928, pp. 45–47.

- ↑ Alexander Lachmann: The fur animals. A manual for furriers and smokers . Baumgärtner's Buchhandlung, Leipzig 1852, pp. 202–203.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), pp. 130-131.

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and rough goods. XXII. Tape. Verlag Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1950. Keyword Russian fur industry

- ↑ Fritz Schmidt: The book of the fur animals and fur . FC Mayer Verlag, Munich 1970.

- ↑ a b Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story, Berlin 1941 Volume 3 . Copy of the original manuscript, p. 130 (→ table of contents) .

- ↑ Alexander Tuma jun: The furrier's practice , published by Julius Springer, Vienna, 1928, pp. 259–261.

- ^ Author collective: Der Kürschner. Technical and textbook for the furrier trade. Published by the vocational training committee of the Central Association of the Furrier Handicraft, JP Bachem publishing house in Cologne. 2nd revised edition. 1956, p. 257.

- ↑ Konrad Haumann: Fur and fur in men's fashion . In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt , February 27, 1942, p. 6.

- ↑ a b c Bernhard Grzimek: The Tsar's noble sable . In: All about fur. December 1963, pp. 48-50.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 46. Primary source J. Kulischer: Russische Wirtschaftsgeschichte . Vol. 1, Jena 1925, p. 116.

- ↑ a b Heinrich Dathe, Berlin; Paul Schöps, Leipzig with the collaboration of 11 specialists: Fur Animal Atlas . Gustav Fischer Verlag, Jena 1986, pp. 173–174.

- ↑ Eberhard Würth von Würthenau: A contribution to the objective assessment of fur . Without publisher information, Heidelberg 1933, p. 31.

- ↑ Paul Schöps; H. Brauckhoff, Stuttgart; K. Häse, Leipzig, Richard König , Frankfurt / Main; W. Straube-Daiber, Stuttgart: The durability coefficients of fur skins In: The fur industry. Volume XV, New Series, No. 2, Hermelin Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig / Vienna 1964, pp. 56–58.

- ↑ Note: The given comparative values ( coefficients ) are the result of comparative tests by furriers and tobacco shops with regard to the degree of apparent wear and tear. The figures are ambiguous; in addition to the subjective observations of shelf life in practice, there are also influences from tanning and finishing as well as numerous other factors in each individual case. More precise information could only be determined on a scientific basis. The division was made in steps of ten percent each.

- ↑ Paul Schöps, Kurt Häse: The fineness of the hair - the fineness classes . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Vol. VI / New Series, 1955 No. 2, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Leipzig, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, pp. 39–40

- ↑ a b F. A. Brockhaus: General Encyclopedia of Sciences and Arts. Published by JS Ed and IG Gruber, Leipzig 1841. Third Section OZ, keyword "Fur"

- ^ A b Siegmund Schapiro, Leipzig: Russian tobacco products . In: Rauchwarenkunde. Eleven lectures on the product knowledge of the fur trade . Verlag der Rauchwarenmarkt, Leipzig 1931, pp. 72–90.

- ↑ Paul Schöps et al.: Hairiness and coloration of the species of marten . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Vol. XVII / New Series 1966 No. 3, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin et al., P. 111. Primary source for the original use of the word Kidus: H. Lomer: Der Rauchwaarenhandel. Leipzig 1864.

- ↑ Fritz Schmidt: The Kidus question . In: The tobacco market. Leipzig February 21, 1941, pp. 1–2, 7.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there). Primary source Hansische Geschichtsblätter , Jg. 1894, Vol. VII

- ↑ a b S. Hopfenkopf: Our fur animals, 1. Zobel . In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt , No. 18, Verlag Der Rauchwarenmarkt, Leipzig February 11, 1930, pp. 3-4.

- ^ R. Russ Winkler: Furs and Furriery . Macniven & Wallace, Edinburgh 1899, p. 39 (English)

- ↑ Sojuzpushnina homepage accessed on February 3, 2011

- ^ Emil Brass : From the realm of fur , publishing house of the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1911, pp. 477-480.

- ↑ Without an author's name: From old German furrier art . In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 44, Leipzig, June 6, 1934, p. 4.

- ↑ Heinrich Hanicke: Handbook for furrier . Published by Alexander Duncker, Leipzig 1895, pp. 63–68.

- ↑ Paul Schöps among others: The material requirement for fur clothing . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Vol. XVI / New Series 1965 No. 1, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin et al., Pp. 7-12. Note: The following measurements for a coat body were taken as a basis: Body = height 112 cm, width below 160 cm, width above 140 cm, sleeves = 60 × 140 cm.

- ↑ ZDF Terra-X . Broadcast on April 20, 2008, queried on January 10, 2011.

- ^ Annual report 2006 of the German Archaeological Institute

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 17: Primary source Hottenroth (see there), p. 88, p. 101, 121.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 30.

- ^ Deutsches Museum, Berlin

- ↑ Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- ↑ a b c Eva Nienholdt, Berlin: fur in the fashion of the 16th century . In: Das Pelzgewerbe , Volume VII / New Series, Hermelin-Verlag Paul Schöps, Berlin / Leipzig 1956, pp. 17-25.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Eva Nienholdt, Berlin: fur in the fashion of the 17th century (see above), p 118. Reprinted with F. Bartsch: Saxon dress codes from the period 1450 to 1750 , Annaberg 1883: 40th report on Royal. Realschule ... zu Annaberg , p. 15.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 66. Primary source P. Lacroix: Moeurs, usages et coutumes au moyen-āge et à L'époque de la Renaissance , Paris 1872, p. 575, moyen-āge

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 66. Primary source L. Friedländer: representations from the moral history of Rome . Leipzig 1922, Vol. III, pp. 72, 77.

- ↑ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: From my life. Poetry and truth . In: Goethe's works: Autobiographical writings I Volume 9, 7th edition. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-406-08495-8 , pp. 85-406.

- ↑ a b c Eva Nienholdt, Berlin: Change of fur fashions in earlier centuries . In: The fur trade . Volume XIX / New Series, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig / Vienna 1968, No. 3, pp. 37–40.

- ^ Robin Netherton, Gale R. Owen-Crocker: Medieval clothing and textiles . Band, 2006 (English)

- ↑ Eva Nienholdt, Berlin: fur in the fashion of the 16th century . In: Das Pelzgewerbe , Volume VII / New Series, 1956 No. 1, pp. 24-25.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan (see there), p. 67. Primary source Friedrich Hottenroth: Handbuch der deutschen Tracht . Stuttgart undated, p. 365.

- ↑ Eva Nienholdt, Berlin: fur in the fashion of the 17th century . In: The fur trade. Volume VII / New Series, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin / Leipzig 1956, No. 3, pp. 110–117.

- ↑ Baran: Fur hats in the British Army. In: The fur trade. Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin / Frankfurt / Leipzig / Vienna, Volume XVII New Series, 1967 No. 2, p. 68.

- ↑ Note: The tails of the spruce marten fetch a higher price, they have been reimported to North America for use in Schtreimels for years. (2009)

- ↑ Paul Cubäus: The whole of Skinning. 2nd Edition. Verlag Alexander Tuma, Leipzig (around 1900), p. 103 - Export only through the Hudson's Bay Company. For 1829 (spring only) = 82,268, for 1890 = 71,918.

- ↑ a b Max Malbin, Königsberg i. Pr .: The international tobacco trade before and after the World War with special consideration of Leipzig . Fr. Oldecops Erben (C. Morgner), Oschatz 1927, p. 54. Estimates by H. Lomer (1864), Cubäus / Tuma (1910)

- ↑ Emil Brass: From the realm of fur. Second improved edition. Verlag Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung, Berlin 1925, p. 434.

- ↑ a b c d e f Vladimir Pawlinin: The sable . Ziemsen Verlag, Wittenberg 1966, p. 5 (export figures, based on Kaplin 1960)

- ↑ Franke / Kroll (see there), p. 51 (only exported skins)

- ↑ Jos. Klein: The Siberian fur trade and its importance for the conquest of Siberia . Inaugural dissertation to obtain a doctorate from the Rheinische Friedrich-Humboldt-Universität Bonn, 1900. S. 38. Primary source v. Baer, p. 138 f.

- ↑ Editor: New York's Fur Queen . In: Kürschner-Zeitung , Verlag Alexander Duncker, Leipzig, between October 15 and November 30, p. 1609.

- ↑ Editor: Liz no longer has the most expensive fur . In: Die Pelzwirtschaft No. 1, CB-Verlag Carl Boldt, Berlin, January 28, 1978, p. 9. Primary source, Abendpost of December 20, 1978.

- ^ Friedrich Malm, August Dietzsch: The art of the furrier. Fachbuchverlag Leipzig 1951, p. 77.

- ↑ Winckelmann Pelz & Markt . Frankfurt / Main, December 14, 2007.

- ^ Pelzmarkt, newsletter of the German fur association . Frankfurt am Main, January 2011, p. 2.

- ↑ Without indication of the author: Sojuzpushnina 190th International Fur Auction in St. Petersburg 28-30 January 2013 In: Pelzmarkt Newsletter 03/13 March 2013, Deutscher Pelzverband, Frankfurt am Main, p. 2.

- ↑ Without indication of the author: Sojuzpushnina, 191st International Fur Auction in St. Petersburg April 28 and 29, 2013 . In: Pelzmarkt , May 2013, Deutscher Pelzverband e. V., Frankfurt am Main, pp. 3-4